Abstract

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate clinical performance of flowable composite in carious and noncarious lesions. An electronic search was conducted using specific databases (PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and LILACS) through March 2017. Clinical trials for restoration of carious and noncarious lesions were included with no date restrictions; follow-up was 6 months at least and dental restorations were evaluated using the United States Public Health Service criteria. The systematic search generated 908 papers, of which 35 papers were included for full-text review. Inclusion criteria were met by eight papers, six papers were for noncarious lesions and two papers were for restoration of carious lesions. The results of this review have shown no statistical or clinical difference between flowable and conventional composites for all tested outcomes in both carious and noncarious lesions. Both materials have shown clinically acceptable scores for all criteria, with no evidence of clinically unacceptable scores except in retention, with a retention rate of 83% in both materials after 36 months. Flowable composites had clinical efficacy after 3 years of service similar to that of conventional composite in both carious and noncarious lesions, these results are based on low quality of evidence. Based on the available literature and the best available evidence, flowable composites can be used in restoration of noncarious cervical lesions and minimally invasive occlusal cavities.

Keywords: Carious, clinical evaluation, flowable composite, noncarious

INTRODUCTION

Flowable composites with low viscosities provided excellent handling characteristics and syringe delivery system which removed some of the obstacles encountered with conventional paste-like composite during placement of resin composite in small-to-moderate-sized cavities, especially in inaccessible areas and might reduce the effects of polymerization shrinkage through increased stress relaxation.[1]

Flowable composites can be applied as a restoration in minimally invasive occlusal cavity preparations, pit and fissure sealants, minimally invasive Class II restorations, and noncarious cervical lesions. Although flowable composites are widely used by dental professionals, their clinical applications have been restricted to some degree by their mechanical shortcomings found, especially in old-generation flowable composites.[2]

Introduction of nanotechnology to flowable composite permitted the development of a composite with the mechanical properties, wear resistance, strength, enhanced polishability, excellent polish retention, translucency of a conventional resin composite and keeping elasticity, adaptation, and favorable handling characteristics of flowable composite with minimized polymerization shrinkage by almost 20%.[3]

Most available literature focused mainly on conventional composite materials, giving limited importance to flowable composites. A recent review[2] evaluated flowable composites based on in vitro studies in literature; it correlated between its composition, physical properties and advantages, disadvantages, indications, contraindications, and clinical significance. This study used in vitro data to predict clinical performance, but randomized clinical trials remain the most accurate study design for evaluating the clinical efficacy of an intervention.

To help in clinical assessment of flowable composite, we are conducting this systematic review to clinically evaluate flowable composite compared to conventional composite based on the literature interest on the material in the past years. The aim of this study is to answer the following question: For restoring carious or noncarious lesions will flowable composite have same clinical performance as conventional composite? To our knowledge, a systematic review on this material has not been conducted yet regarding its clinical performance.

METHODS

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

(1) Clinical trials evaluating resin composite restorations regardless of the indication (carious or noncaries lesions); (2) English language; (3) no date restrictions; (4) follow-up for participants 6 months at least; (5) evaluation using the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) criteria (retention, postoperative sensitivity, secondary caries, color match, anatomical form, marginal discoloration, marginal adaptation, and surface texture); and (6) articles selected had to include the search terms either in the title or abstract were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Other languages; (2) follow-up for participants <6 months; (3) in vitro, animal, and observational studies; and (4) other methods for evaluation of dental restorations were excluded from the study.

Search strategy

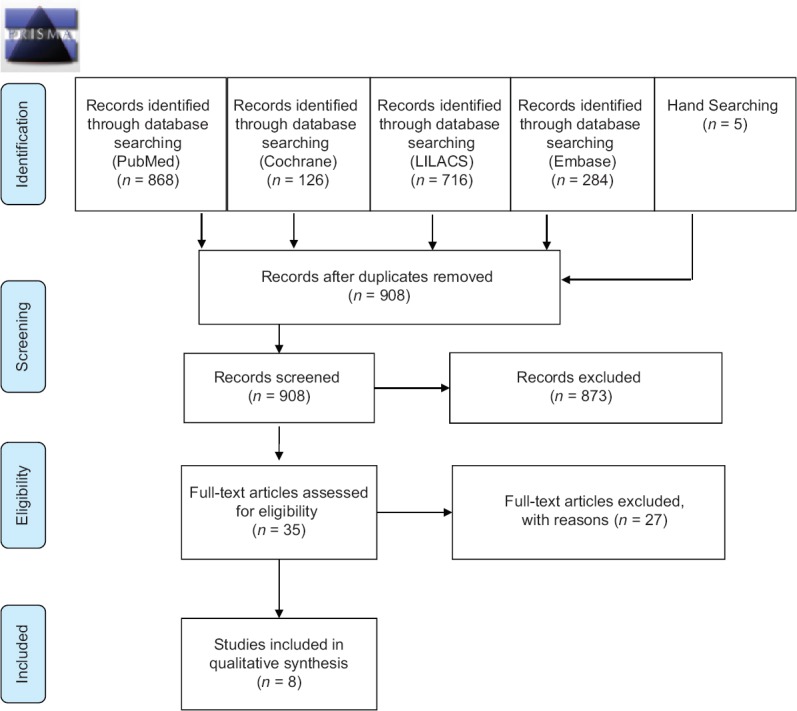

The results of this review have been searched into four databases Medline through PubMed, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, LILACS, and Embase through June 2017 with the search terms “(((((flowable composite) OR flowable resin composite) OR flowable resin composites) OR flowable composite resin)) AND (((((((((resin composite) OR composite resin) OR conventional resin composite) OR conventional composite) OR high filled composite)))))”. Unpublished articles, gray literature, journals (Journal of Advanced Dental Research, Journal of Adhesive Dentistry, American Journal of Dentistry, Dental Materials, Journal of Dentistry, and Operative Dentistry), and abstracts were screened and snowballing of references was performed. Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Inclusion of studies was independently decided by both reviewers; when there was a conflict, a consensus was reached by discussion. Journals or authors were not blinded to reviewers. In this systematic search, a total of 908 articles were found on different databases related to our search terms. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, only eight articles (six noncarious[4,5,6,7,8,9] and two carious[10,11]) were available for data extraction and data synthesis; results of the search strategy were summarized in PRISMA flow diagram [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram

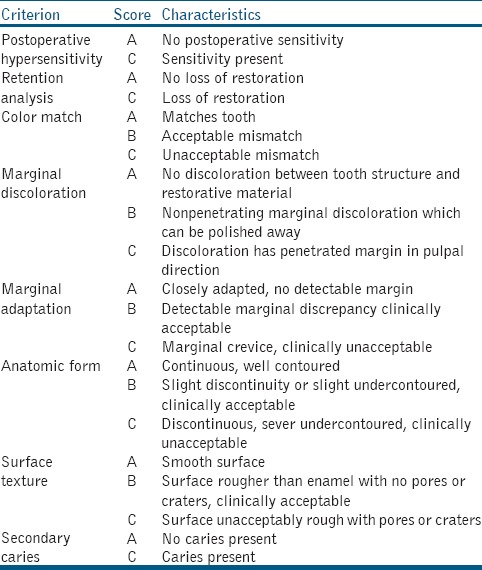

Data were extracted by two calibrated reviewers using customized extraction tables for demographic data, methodology, and results of all included articles. Performance of both materials was compared for each criterion by collapsing data into two groups, either alpha or nonalpha values (as a result of a limited number of nonalpha values), to simplify data synthesis and to accurately differentiate between the performance of both materials.[11] Alpha scores of all outcomes assessed were tabulated in the form of absolute risk for intervention and control independently, and risk ratio was used to compare both of them to each other. The following outcomes were assessed: retention, postoperative sensitivity, marginal discoloration, marginal adaptation, color match, anatomical form, surface texture, and secondary caries and described in Table 1.

Table 1.

United States Public Health Service evaluation criteria for dental restorations

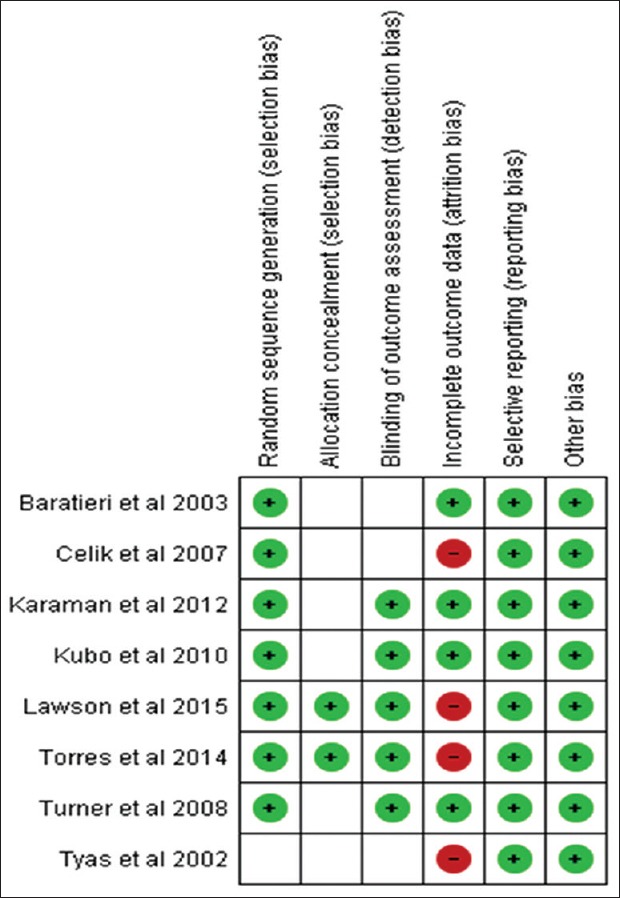

Quality assessment

The quality of each included study was assessed in duplicate by two independent reviewers. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion to reach a consensus. Risk of bias was judged for each study. Studies were considered to be at low risk of bias if there was appropriate sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, adequate information on withdrawals, and reporting [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment

Statistics

In this meta-analysis, both materials were compared using risk ratio, and results were analyzed using inverse variance statistical test, fixed effect model, at 95% confidence interval (Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3, 2014). A total of 348 restorations in flowable composite group and 383 restorations in conventional composite group were included; after 24 months, 260 and 286 restorations remained for follow-up in flowable and conventional composite groups, respectively. Dropouts were reported in most of studies and were equally distributed in flowable and conventional groups with a retention rate of 75%.

RESULTS

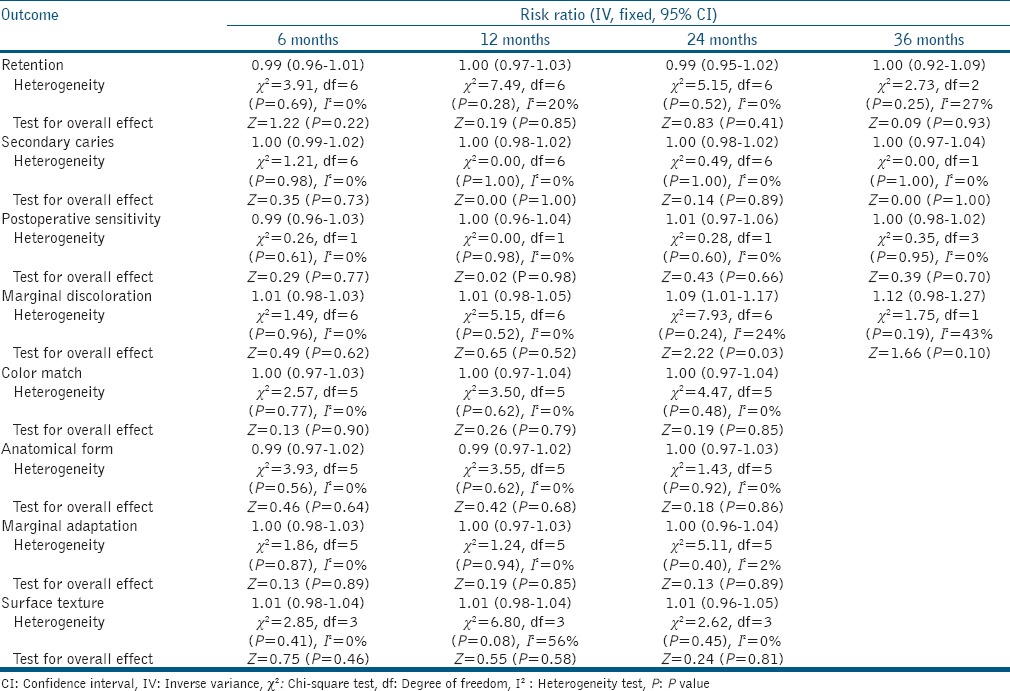

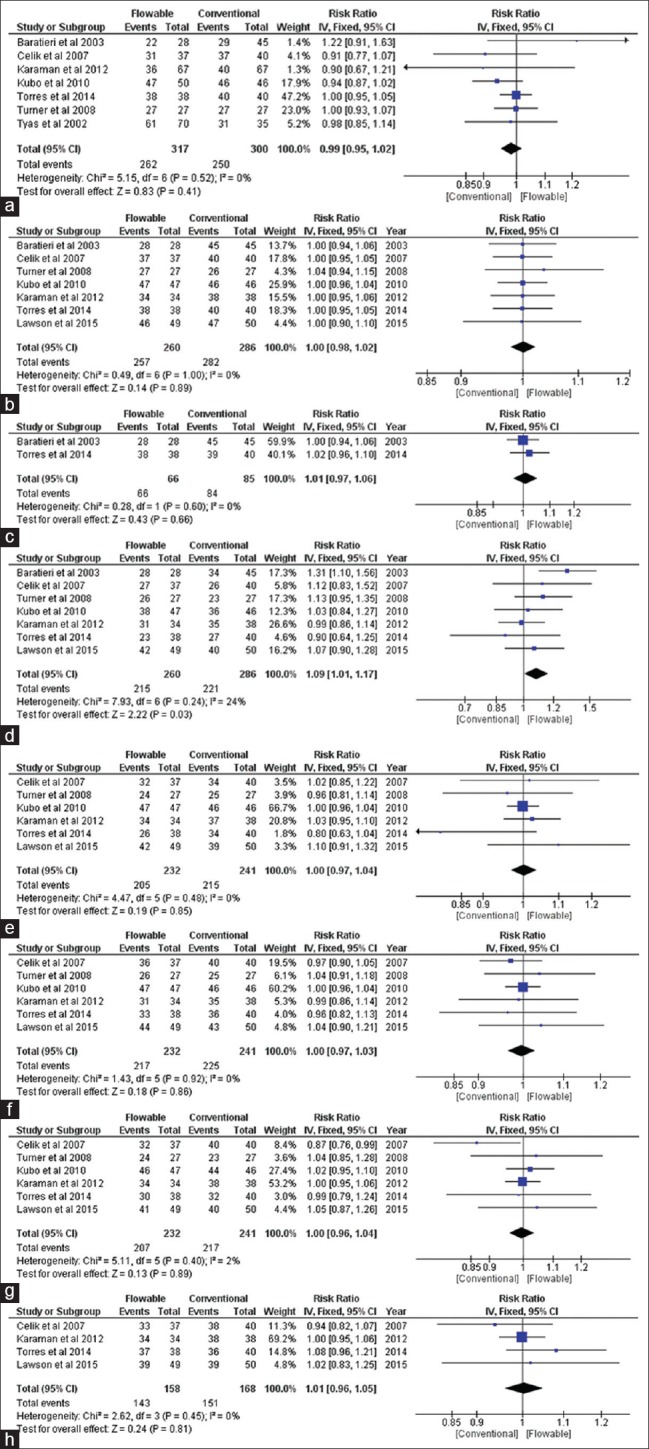

There was no statistical or clinical difference between flowable and conventional composites in all tested outcomes after 6, 12, 24, and 36 months in carious and noncarious lesions as shown in Table 2. Both materials have shown clinically acceptable scores for all criteria, with no evidence of clinically unacceptable scores except in retention, with a retention rate of 83% for both materials. Figure 3 shows the forest plot for all outcomes after 24 months with no evidence of clinical difference between both materials.

Table 2.

Assessment of flowable and conventional composites using the United States Public Health Service criteria after 6, 12, 24, and 36 months

Figure 3.

Forest plot for different outcomes showing no clinical difference between both materials, (a) Retention, (b) Secondary caries, (c) Postoperative hypersensitivity, (d) Marginal discoloration, (e) Color match, (f) Anatomical form, (g) Marginal adaptation, (h) Surface texture

DISCUSSION

Systematic reviews based on clinical trials require reliable and appropriate criteria to evaluate the clinical performance of dental restorations. The modified USPHS criteria and the federation dentaire internationale (FDI) criteria are the most frequently used criteria for the assessment of dental restoration. In this review, articles using USPHS criteria were included in quantitative synthesis and meta-analyses as it was difficult to pool results from USPHS and FDI criteria together. USPHS criterion is a long-standing method for the evaluation of dental restorations in clinical trials and was the system of choice in studies included in this review while USPHS system has served well for clinical evaluation; there are some concerns about the sensitivity of the approach in short-term clinical evaluations. However, this scoring system is still being used in the clinical trials to compare outcomes with the previous ones that use the same system.[12] This method remains the most commonly used for evaluating important characteristics of dental restorations, such as postoperative sensitivity, secondary caries, marginal discoloration, adaptation, and color match, and it is able to generate data that are of a clinical relevance. A clinical study used FDI criteria for assesment of flowable composite in posterior restorations, results were similar to the results of this review, with no difference between flowable and conventional composites after 36 months in Class I and Class II cavities.[13]

In this review, six studies[4,5,6,7,8,9] used flowable composite in noncarious cervical lesions, and there was no statistical or clinical differences between flowable and conventional composites in all studies. Flowable composites have the ability to relief stresses at the adhesive interfaces and have a stress-breaking effect in relieving thermal and occlusal stresses as well as polymerization shrinkage, and this ability is due to low modulus of elasticity of flowable composites when compared to conventional paste-like composites; therefore, the use of a flowable resin composite in noncarious cervical lesions was recommended as being beneficial.[8,9]

However, clinical application of flowable composites in posterior restorations has been restricted to some degree by their mechanical shortcomings found, especially in early generation flowable composites.[2] Two studies[10,11] in this review used flowable composite in carious posterior restorations; in addition to one study not included in this systematic review,[13] in these three studies, there was no statistical or clinical difference between flowable and conventional composites in posterior restorations. New generations of flowable composites were developed using nanotechnology creating a composite with properties of conventional resin composite and keeping elasticity, adaptation, and favorable handling characteristics of flowable composite with minimized polymerization shrinkage; this enhanced mechanical and physical properties of flowable composites and enabled their usage in minimally invasive posterior restorations.[3]

Limitations in this review include moderate-to-high risk of bias, dropouts, and short-term follow-up duration. Three-year follow-up could provide some information about the clinical performance of composite materials, but this period is too short for the development of any significant failures. Clinical studies are the last and the most important step to evaluate new materials and techniques; further, long-term clinical studies are required to confirm our results.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the limitations of this review the following conclusions can be derived:

Flowable composites had clinical efficacy after 3 years of service similar to that of conventional composite in both carious and noncarious lesions.

These results are based on a low quality of evidence.

Development of nanotechnology has opened new horizons for flowable composite in the future.

Flowable composites are relatively newer than conventional composites, and results are inconclusive about their clinical performance in clinical situations.

Recommendations

Based on the available literature and the best available evidence, flowable composites can be used in restoration of noncarious cervical lesions and minimally invasive occlusal cavities.

Long-term high-quality clinical studies are needed for further evaluation of flowable composites in carious and noncarious lesions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

I acknowledge this piece of work to Prof. Dr. Iman Abd El Wahab Radi, Professor of Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry Cairo University for her help and guidance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Attar N, Tam LE, McComb D. Flow, strength, stiffness and radiopacity of flowable resin composites. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:516–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baroudi K, Rodrigues JC. Flowable resin composites: A Systematic review and clinical considerations. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:ZE18–24. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12294.6129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abiodun-Solanke I, Ajayi D, Arigbede A. Nanotechnology and its application in dentistry. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4:S171–7. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.141951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyas MJ, Burrow MF. Three-year clinical evaluation of one-step in non-carious cervical lesions. Am J Dent. 2002;15:309–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baratieri LN, Canabarro S, Lopes GC, Ritter AV. Effect of resin viscosity and enamel beveling on the clinical performance of class V composite restorations: Three-year results. Oper Dent. 2003;28:482–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celik C, Ozgünaltay G, Attar N. Clinical evaluation of flowable resins in non-carious cervical lesions: Two-year results. Oper Dent. 2007;32:313–21. doi: 10.2341/06-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner EW, Shook LW, Ross JA, deRijk W, Eason BC. Clinical evaluation of a flowable resin composite in non-carious class V lesions: Two-year results. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 2008;88:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubo S, Yokota H, Yokota H, Hayashi Y. Three-year clinical evaluation of a flowable and a hybrid resin composite in non-carious cervical lesions. J Dent. 2010;38:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karaman E, Yazici AR, Ozgunaltay G, Dayangac B. Clinical evaluation of a nanohybrid and a flowable resin composite in non-carious cervical lesions: 24-month results. J Adhes Dent. 2012;14:485–92. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.a27794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocha Gomes Torres C, Rêgo HM, Perote LC, Santos LF, Kamozaki MB, Gutierrez NC, et al. A split-mouth randomized clinical trial of conventional and heavy flowable composites in class II restorations. J Dent. 2014;42:793–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson NC, Radhakrishnan R, Givan DA, Ramp LC, Burgess JO. Two-year randomized, controlled clinical trial of a flowable and conventional composite in class I restorations. Oper Dent. 2015;40:594–602. doi: 10.2341/15-038-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celik C, Arhun N, Yamanel K. Clinical evaluation of resin-based composites in posterior restorations: 12-month results. Eur J Dent. 2010;4:57–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitasako Y, Sadr A, Burrow MF, Tagami J. Thirty-six month clinical evaluation of a highly filled flowable composite for direct posterior restorations. Aust Dent J. 2016;61:366–73. doi: 10.1111/adj.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]