Abstract

Fagaceae is one of the largest and economically important taxa within Fagales. Considering the incongruence among inferences from plastid and nuclear genes in the previous Fagaceae phylogeny studies, we assess the performance of plastid phylogenomics in this complex family. We sequenced and assembled four complete plastid genomes (Fagus engleriana, Quercus spinosa, Quercus aquifolioides, and Quercus glauca) using reference-guided assembly approach. All of the other 12 published plastid genomes in Fagaceae were retrieved for genomic analyses (including repeats, sequence divergence and codon usage) and phylogenetic inference. The genomic analyses reveal that plastid genomes in Fagaceae are conserved. Comparing the phylogenetic relationships of the key genera in Fagaceae inferred from different codon positions and gene function datasets, we found that the first two codon sites dataset recovered nearly all relationships and received high support. Thus, the result suggested that codon composition bias had great influence on Fagaceae phylogenetic inference. Our study not only provides basic understanding of Fagaceae plastid genomes, but also illuminates the effectiveness of plastid phylogenomics in resolving relationships of this intractable family.

Keywords: Fagaceae, plastid genome, topological incongruence, codon composition bias, phylogenomics

Introduction

Due to the rapid development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, genomic data have been increasingly used to explore plant phylogeny. With respect to genomic complexity, sequencing cost, analysis methods and the degree of recombination of different genomes (organelle genomes and nuclear genome), the plastid genome presents obvious advantages (e.g., generally recombination-free, uniparental inheritance, highly conserved structure) (Birky et al., 1983; Jansen and Ruhlman, 2012). Recently, the use of plastid genomes in plant phylogenetic analyses is expanding and great progress has been achieved (Jansen et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2007, 2010; Parks et al., 2009; Barrett et al., 2013, 2016; Nikiforova et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2014; Carbonell-Caballero et al., 2015). It is widely accepted that plastids are derived from an endosymbiotic event (Keeling, 2010, and references therein). Most angiosperm plastid genomes have a typical quadripartite structure, with two copies of inverted repeat regions (IR) separating the small and large single copy regions (SSC and LSC, respectively) (Jansen et al., 2005; Jansen and Ruhlman, 2012). Although the structure of the plastid genome is generally highly conserved, different levels of genomic upheaval (such as gene or IR losses, large-scale rearrangements) have been detected in Campanulaceae, Fabaceae, Geraniaceae, Oleaceae and many other families (Cosner et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2007; Cai et al., 2008; Guisinger et al., 2010, 2011; Martin et al., 2014).

Fagaceae is a diverse and ecologically dominant group throughout the Northern Hemisphere, which consists of 10 genera and ca. 900 species (Manos et al., 2001, 2008; Oh and Manos, 2008). In Fagaceae, the genus Quercus is species-rich (approximately 500 species worldwide) and has received substantial attention in phylogeny and biogeography studies compared with other genera (e.g., Manos et al., 1999; Cavender-Bares et al., 2004; Zeng et al., 2011; Gugger and Cavender-Bares, 2013). With many meaningful evolutionary topics to explore, Fagaceae is among the best studied woody plant families. For example, extensive hybridization resulting in perplexing taxonomy; rich fossil record for macroevolutionary studies; highly disparate fruit forms for studies of dispersal mode; and phylogenetic relationships of this species-rich family.

Previously, molecular phylogenies obtained from nuclear data appeared more plausible than those from plastid data (Manos et al., 2001; Denk and Grimm, 2010; Hubert et al., 2014), owing to their congruence with morphological evidence, including the fossil record (e.g., Denk and Grimm, 2009; Grímsson et al., 2015, 2016). Notably, combining two nuclear loci (ITS and CRC) with data from three plastid regions (trnK-matk/trnK, atpB-rbcL and ndhF) failed to resolve all oaks as one clade (Manos et al., 2008). Moreover, the same phenomenon was observed in Simeone et al. (2016) and Vitelli et al. (2017) that only used three plastid markers (both used plastid regions: rbcL, trnK/matK, and trnH-psbA). However, when using two nuclear loci (ITS and CRC) alone, they clarified the relationships of Fagaceae, in particular, oaks were supported as monophyletic (Oh and Manos, 2008). The phenomenon that plastid data and nuclear data generate conflicting (incongruent) phylogenies has also been observed in other plant groups, such as Senecioneae, Helichrysum and Neotropical Catasetinae (Pelser et al., 2010; Galbany-Casals et al., 2014; Pérez-Escobar et al., 2015). Topological incongruence may result from different genetic backgrounds (maternal or biparental inheritance) and substitution rates of plastid and nucleus (Tepe et al., 2011). Moreover, biological processes, such as chloroplast capture (by hybridization or introgression) and incomplete lineage sorting may also be responsible for the phenomenon (Stegemann et al., 2012; Pérez-Escobar et al., 2015).

In general, improvements in tree resolution of Fagaceae had been offered in the previous molecular studies. Nuclear markers, used in Fagaceae phylogeny inference, yielded relatively low support for the monophyletic genus Quercus (MP and ML bootstrap support values were 60 and 52, respectively) (Oh and Manos, 2008). Considering the performances of the few molecular markers in Fagaceae phylogenetic inferences and the ability of plastid phylogenomics (high resolution and strong support) in the earlier studies, we explore whether plastid genome-scale data have the ability to infer strongly supported phylogenetic relationships for Fagaceae, especially for the monophyletic genus Quercus.

Materials and methods

Taxon sampling and plant material

In total, 16 plastid genomes belonging to the key genera of Fagaceae are analyzed in this study, including four newly generated plastid genomes (F. engleriana, Q. glauca, Q. spinosa, and Q. aquifolioides) and all of the published plastid genomes in Fagaceae. The other 12 species are Trigonobalanus doichangensis, Quercus rubra (Alexander and Woeste, 2014), Quercus baronii (Yang et al., 2017), Quercus aliena, Quercus aliena var. acuteserrata, Quercus variabilis, Quercus dolicholepis (Yang et al., 2016), Quercus edithiae, Castanopsis echinocarpa, Lithocarpus balansae, Castanea mollissima (Jansen et al., 2011), and Castanea pumila var. pumila (Dane et al., 2015). The collecting and GenBank accession information for the analyzed taxa are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Accessions in this study with taxonomic, collection locality, Illumina read, and coverage information.

| Species | Genus | Collection locality | GenBank number | Assembly reads | Mean coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercus rubra | Group Lobatae, Quercus | / | JX970937 | / | / |

| Quercus aliena | Group Quercus, Quercus | / | KU240007 | / | / |

| Quercus aliena var. acuteserrata | Group Quercus, Quercus | / | KU240008 | / | / |

| Quercus baronii | Group Ilex, Quercus | / | KT963087 | / | / |

| Quercus dolicholepis | Group Ilex, Quercus | / | KU240010 | / | / |

| Quercus variabilis | Group Cerris, Quercus | / | KU240009 | / | / |

| Quercus aquifolioides | Group Ilex, Quercus | Panzhihua, Sichuan, China | KX911971 | 788,550 | 616x |

| Quercus spinosa | Group Ilex, Quercus | Dali, Yunnan, China | KX911972 | 766,767 | 591x |

| Quercus glauca | Group Cyclobalanopsis, Quercus | Chenshan Botanical Garden, Shanghai, China | KX852399 | 427,422 | 329 x |

| Quercus edithiae | Group Cyclobalanopsis, Quercus | / | KU382355 | / | / |

| Castanea mollissima | Castanea | / | HQ336406 | / | / |

| Castanea pumila var. pumila | Castanea | / | KM360048 | / | / |

| Castanopsis echinocarpa | Castanopsis | / | KJ001129 | / | / |

| Lithocarpus balansae | Lithocarpus | / | KP299291 | / | / |

| Trigonobalanus doichangensis | Trigonobalanus | / | KF990556 | / | / |

| Fagus engleriana | Fagus | Wuhan Botanical Garden, Wuhan, China | KX852398 | 362,613 | 281x |

DNA extraction, illumina sequencing, assembly, and annotation

Total genomic DNA was extracted for the four species from silica-dried leaf material following the modified CTAB method (Doyle, 1987). The paired-end (PE) library was constructed using TruSeq DNA sample preparation kits. Sequencing was completed on an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform with the average read length of 125 bp, yielding at least 2 GB clean data for each species. All of the above work were conducted by Biomarker Technologies Inc. (Beijing, China). Firstly, all of the raw reads were trimmed using NGS QC Toolkit_v.2.3.3 with the default parameters set (Patel and Jain, 2012). Reference-guided assembly was then used to reconstruct the plastid genomes with the programs MIRA 4.0.2 (Chevreux et al., 2004) and MITObim v1.7 (Hahn et al., 2013). In the process, plastid genomes of Q. rubra (JX970937), Q. aliena (KU240007), and C. mollissima (HQ336406) were used as reference genomes. The complete plastid genomes were annotated using the program DOGMA (Wyman et al., 2004), and then manually corrected by comparing them with the complete plastid genomes of the other published Fagaceae species in GENEIOUS R8 (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand).

Codon usage bias analysis

The protein-coding genes (CDS) were extracted from plastid genomes with the following constraints: (1) the presence of proper initial (ATG) and termination codons (TAA, TGA and TAG); (2) CDS length was greater than 300 bp to avoid sampling bias (Wright, 1990). Finally, 53 common CDS for each plastome were analyzed.

The GC content of the complete plastid genomes and 53 common analyzed CDS (GCg and GCc), as well as GC contents of the first, second, and third codon positions of analyzed CDS (GC1, GC2 and GC3, respectively) were calculated by GENEIOUS R8. Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) is the ratio of the observed frequency of a codon to the expected frequency and is a good indicator of codon usage bias (Sharp and Li, 1986). When synonymous codons are used less frequently than expected, RSCU value is less than 1, otherwise the value is greater than 1 (Gupta et al., 2004). The above work was completed by MEGA 5.0 (Tamura et al., 2011).

Repeat elements analysis

REPuter (Kurtz et al., 2001) was used to identify dispersed and palindromic repeats within plastid genomes. We focused on the repeats having a minimal size of 30 bp and 90% or greater similarity between the two repeat copies. The maximum distance between palindromic repeats is 3 Kb. Tandem repeats (>10 bp in length) were detected using online program Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF) (Benson, 1999) with default parameters. The minimum alignment score and maximum period size set as 80 and 500, respectively. All of the above parameters were set based on some related plastid studies (Huang et al., 2013, 2014; Rousseau-Gueutin et al., 2015). All found repeats were manually verified and the redundant results were removed. In Yang et al. (2016), all three types of repeats had been identified in Q. dolicholepis, Q. variabilis, Q. aliena, Q. aliena var. acuteserrata and Q. baronii, which were processed in the same way as this study. Therefore, repeat elements were detected only in the other 11 plastid genomes.

Sequence divergence analysis

Sequence divergence was evaluated for protein-coding sequences by calculating pairwise distance between each two species. Pairwise distances were calculated using MEGA 5.0 with K2p evolution model (Kimura, 1980). A visual alignment of complete plastid genomes was generated in mVISTA (Frazer et al., 2004).

Phylogenetic analysis

To evaluate the effect of codon composition bias and gene function on phylogenetic estimation, we respectively constructed the aligned matrices of shared protein-coding genes, codon positions 1 + 2, codon position 3, and 5 functional categories of protein-coding genes (Chang et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2012) for the Fagaceae phylogeny. All of the above analyzed matrices were obtained from 76 shared protein-coding genes. The extraction of different positions of codon was conducted by MEGA 5.0. Populus trichocarpa (EF489041) (Tuskan et al., 2006) and Theobroma cacao (HQ244500) were chosen as outgroups. Sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013) in GENEIOUS R8 with the default parameters set.

All phylogenetic analyses were performed using maximum likelihood (ML) methods and Bayesian inference (BI), which were conducted using RAxML v7.2.8 (Stamatakis, 2006) and MrBayes v3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003), respectively. The ML tree was inferred with GTR+G model and 1000 rapid bootstrap replicates. The best-fitting model for BI analyses was determined using Modeltest 3.7 (Posada and Crandall, 1998) based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Two independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs were performed for 2 million generations with sampling every 100 generations, and the first 25% of the trees were discarded as burn-in.

Results

Plastid assembly, genome characteristics, and codon usage bias

Four plastids (F. engleriana, Q. spinosa, Q. aquifolioides, and Q. glauca) were generated in the current study. Illumina sequencing produced large data sets. 362,613 (F. engleriana) to 788,550 (Q. aquifolioides) reads were assembled to generate the plastid genomes, ranging from 281 × to 616 × coverage (Table 1). These plastid genomes possess the typical quadripartite structure, ranging from 158,346 bp (F. engleriana) to 161,225 bp (Q. aquifolioides) (Table 2). Except F. engleriana, the other three plastid genomes share identical gene content and gene order, encoding a total of 134 genes, including 86 protein-coding genes (CDS), 40 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and 8 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes (Table 2). Fagus engleriana encodes a total of 131 genes, containing the same numbers of tRNA and rRNA genes except for three lost protein-coding genes (rps16, infA, and rpl22) compared with the other three species.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Fagaceae plastid genomes.

| Species | Genome size (bp) | LSC (bp) | SSC (bp) | IR (bp) | Number of genes | Pseudo gene | Number of protein-coding genes | Number of tRNA genes | Number of rRNA genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercus rubra | 161,304 | 90,541 | 19,025 | 51,738 | 137 | / | 89 | 40 | 8 |

| Quercus aliena | 161,150 | 90,444 | 19,054 | 51,652 | 134 | / | 86 | 40 | 8 |

| Quercus aliena var. acuteserrata | 161,153 | 90,457 | 19,044 | 51,652 | 134 | / | 86 | 40 | 8 |

| Quercus baronii | 161,072 | 90,341 | 19,045 | 51,686 | 134 | / | 86 | 40 | 8 |

| Quercus dolicholepis | 161,237 | 90,461 | 19,048 | 51,728 | 134 | / | 86 | 40 | 8 |

| Quercus variabilis | 161,077 | 90,387 | 19,056 | 51,634 | 134 | / | 86 | 40 | 8 |

| Quercus aquifolioides* | 161,225 | 90,535 | 19,000 | 51,690 | 134 | / | 86 | 40 | 8 |

| Quercus spinose* | 161,156 | 90,441 | 18,997 | 51,718 | 134 | / | 86 | 40 | 8 |

| Quercus glauca* | 160,798 | 90,229 | 18,907 | 51,662 | 134 | / | 86 | 40 | 8 |

| Quercus edithiae | 160,988 | 90,352 | 18,954 | 51,682 | 128 | rpl22, ycf15(x2) | 87 | 30 | 8 |

| Castanea mollissima | 160,799 | 90,432 | 18,995 | 51,372 | 130 | rpl22, ycf1 | 83 | 37 | 8 |

| Castanea pumila var. pumila | 160,603 | 90,249 | 18,976 | 51,378 | 131 | rpl22 | 83 | 39 | 8 |

| Castanopsis echinocarpa | 160,647 | 90,394 | 18,995 | 51,258 | 132 | / | 84 | 40 | 8 |

| Lithocarpus balansae | 161,020 | 90,596 | 19,160 | 51,264 | 134 | / | 87 | 39 | 8 |

| Trigonobalanus doichangensis | 159,938 | 89,374 | 19,292 | 51,272 | 128 | / | 81 | 39 | 8 |

| Fagus engleriana* | 158,346 | 87,667 | 18,895 | 51,784 | 131 | / | 83 | 40 | 8 |

The 4 newly generated plastid genomes were marked in *.

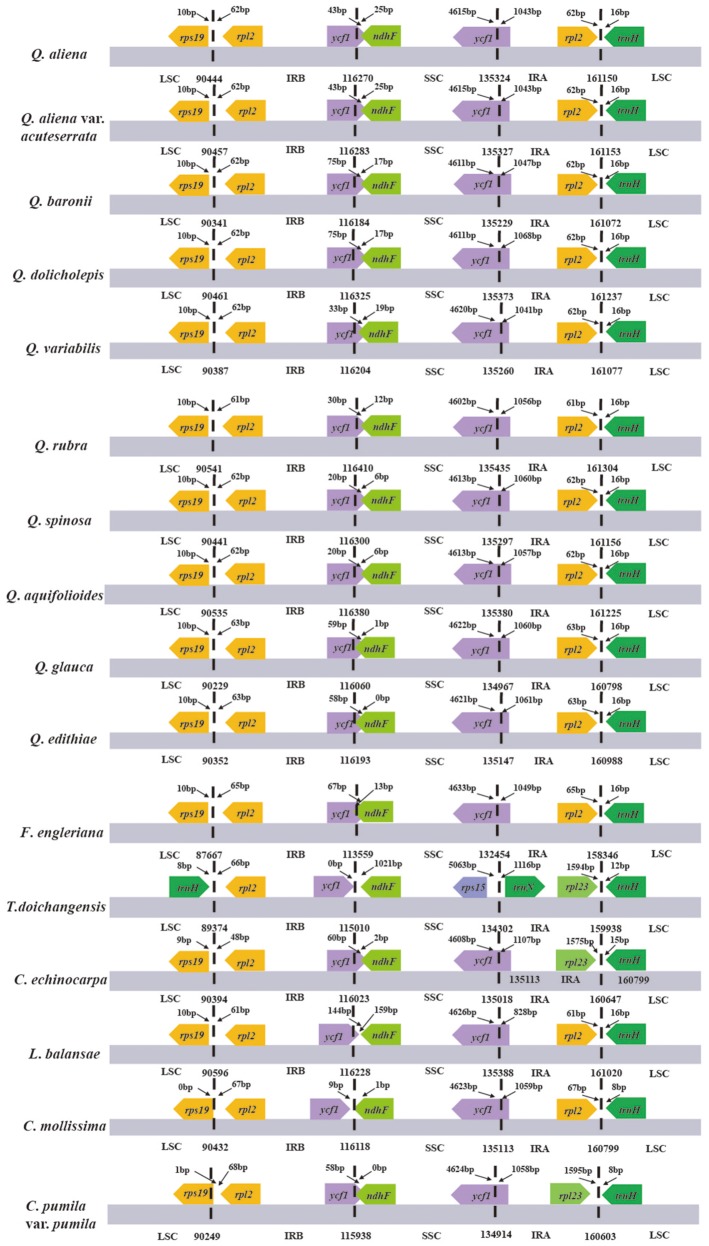

A comparison of the major characteristics of all available Fagaceae plastid genomes is shown in Table 2. F. engleriana has the smallest plastid genome (158,346 bp), whereas Q. rubra has the largest (161,304 bp). The number of encoded genes varies from 128 (T. doichangensis) to 137 (Q. rubra). In particular, the number of tRNA genes in Q. edithiae is significantly decreased compared with other species. Gene differences are provided as Supplemental Data (Table S1). There exist pseudogenes in Q. edithiae, C. mollissima and C. pumila var. pumila. The IR/SC boundary regions in Fagaceae show slight differences (Figure 1). For example, the extended length of ycf1 into SSC region range from 0 (T. doichangensis) to 144 bp (L. balansae).

Figure 1.

The comparison of the LSC, IR, and SSC border regions among the Fagaceae plastid genomes. Numbers above the gene features mean the distance from the end of gene to the boundary region. These features are not to scale.

Overall, GC content levels of different species are very close in the same region (such as CDS, different codon positions; Table 3). Both the genome-wide GC content (GCg) (about 36.8%) and CDS GC content (GCc) (about 38.6%) indicate that the plastid genome is AT-rich. Within the analyzed CDS, the mean values of GC content for the first, second and third codon positions of 16 Fagaceae species are 46.4, 38.4, and 31.0%, respectively.

Table 3.

GC content of sequences in Fagaceae plastid genomes.

| Species | Number of analyzed CDS | GCg (%) | GCc (%) | GC1 (%) | GC2 (%) | GC3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercus rubra | 53 | 36.8 | 38.6 | 46.3 | 38.3 | 31.0 |

| Quercus aliena | 53 | 36.8 | 38.6 | 46.4 | 38.4 | 30.9 |

| Quercus aliena var. acuteserrata | 53 | 36.8 | 38.6 | 46.4 | 38.4 | 30.9 |

| Quercus baronii | 53 | 36.8 | 38.6 | 46.4 | 38.4 | 31.0 |

| Quercus dolicholepis | 53 | 36.8 | 38.6 | 46.4 | 38.4 | 30.9 |

| Quercus variabilis | 53 | 36.8 | 38.6 | 46.4 | 38.4 | 31.0 |

| Quercus aquifolioides | 53 | 36.8 | 38.6 | 46.4 | 38.4 | 31.0 |

| Quercus spinosa | 53 | 36.8 | 38.6 | 46.4 | 38.3 | 31.0 |

| Quercus glauca | 53 | 36.9 | 38.6 | 46.5 | 38.4 | 31.0 |

| Quercus edithiae | 53 | 36.9 | 38.6 | 46.5 | 38.4 | 31.0 |

| Castanea mollissima | 53 | 36.8 | 38.5 | 46.4 | 38.3 | 30.9 |

| Castanea pumila var. pumila | 53 | 36.8 | 38.5 | 46.3 | 38.3 | 30.9 |

| Castanopsis echinocarpa | 53 | 36.7 | 38.6 | 46.4 | 38.4 | 31.0 |

| Lithocarpus balansae | 53 | 36.7 | 38.5 | 46.3 | 38.3 | 30.9 |

| Trigonobalanus doichangensis | 53 | 37.0 | 38.8 | 46.6 | 38.5 | 31.3 |

| Fagus engleriana | 53 | 37.1 | 38.5 | 46.5 | 38.3 | 30.8 |

GCg: GC content of whole genome; GCc: GC content of 53 analyzed CDS; GC1, GC2, GC3: GC content at first, second and third codon positions, respectively.

For the analyzed CDS, the frequency of codon usage in each species is summarized in Table S2. Codon usage bias is fairly similar across Fagaceae. In all species, the most and least prevalent amino acids always are leucine (approximately 10.5%) and cysteine (approximately 1.2%), respectively. Moreover, except Met and Trp that are encoded by only one codon, all the other amino acids show that some codons appear to be used more frequently than others. For example, synonymous codons UUA, UUG, CUU, CUC, CUA and CUG encode leucine and the corresponding RSCU values for these six codons in F. engleriana are 1.83, 1.24, 1.31, 0.40, 0.82, and 0.40, respectively, as expected from the low GC content of CDS.

Repeat elements

A total of 440 repeat elements are identified for these three repeat types in the 16 complete plastid genomes (Table 4). The numbers of tandem, dispersed, and palindromic repeats are 145, 199 and 96, respectively. IR regions have the most repeats (220, 50.0%), followed with LSC (170, 38.6%) and SSC (50, 11.4%). From another point of view, the majority of repeats are located in intergenic spacer regions (234, 53.2%), and the minority are found in introns (89, 20.2%). Ratios of number of repeat bases to number of bases in the region (number of repeat bases / number of bases in the region) for different region comparisons show that IR regions and introns host the highest ratios (1.66 and 1.88%, respectively). Only a few genes (e.g., ycf1, ycf2, atpF, psaA, psaB, and some tRNA genes) possess repeat elements. All dispersed and palindromic repeats occur in a narrower size (30–40 bp), except for a 72 bp dispersed repeat in Q. edithiae. Regarding the tandem repeats, shorter repeats are common (< 40 bp), whereas only 5 longer repeats (> 40 bp) are detected (4 in Q. edithiae and 1 in F. engleriana). Moreover, the majority of 10–20 bp tandem repeats and 21–30 bp tandem repeats are found in introns and genes, respectively. Overall, number and distribution of repeat elements are conserved across these Fagaceae species (Table S3).

Table 4.

Analyses of repeat elements in Fagaceae plastid genomes.

| Location | Tandem repeats | Dispersed repeats | Palindromic repeats | All kinds of repeats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of different length repeats (10–20 bp/21–30 bp/31–40 bp/>40 bp) | Number of repeat bases/number of bases in the region | Number of different length repeats (30–40 bp/>40 bp) | Number of repeat bases/number of bases in the region | Number of different length repeats (30–40 bp/>40 bp) | Number of repeat bases/number of bases in the region | Number of repeat bases/number of bases in the region | |

| Complete plastid genomes | 145 (53/50/37/5) | 8,459/2,572,513 | 199 (198/1) | 12,832/2,572,513 | 96 (96/0) | 6,150/2,572,513 | 27,441/2,572,513 |

| LSC | 40 (20/12/4/4) | 2219/1,442,900 | 97 (97/0) | 6,081/1,442,900 | 33 (33/0) | 2,050/1,442,900 | 10,350/1,442,900 |

| SSC | 11 (3/6/1/1) | 634/304,443 | 21 (20/1) | 1,670/304,443 | 18 (18/0) | 1,090/304,443 | 3,394/304,443 |

| IR | 94 (30/32/32/0) | 5,606/825,170 | 81 (81/0) | 5,081/825,170 | 45 (45/0) | 3,010/825,170 | 13,697/825,170 |

| Intergenic spacer regions | 79 (25/17/33/4) | 4,451/828,186 | 95 (95/0) | 6,289/828,186 | 60 (60/0) | 4,094/828,186 | 14,834/828,186 |

| Introns | 28 (26/0/1/1) | 1,388/284,012 | 41 (40/1) | 2,849/284,012 | 20 (20/0) | 1,096/284,012 | 5,333/284,012 |

| Genes | 38 (2/33/3/0) | 2,620/1,460,315 | 63 (63/0) | 3,694/1,460,315 | 16 (16/0) | 960/1,460,315 | 6,714/1,460,315 |

Numbers of different length repeats are given in brackets.

Sequence divergence

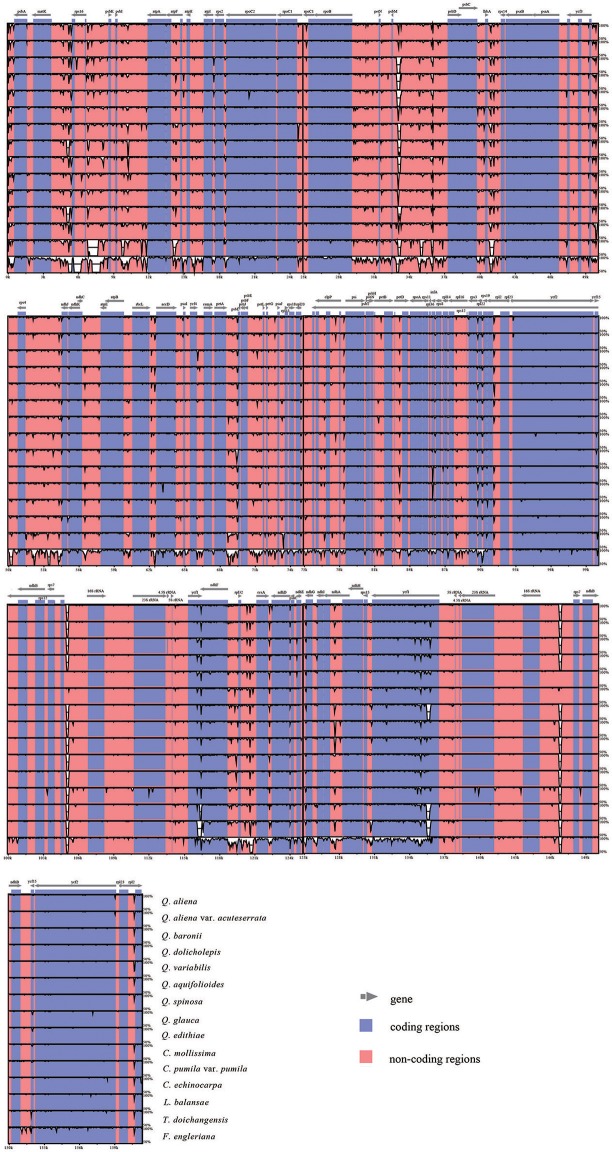

With Q. rubra as a reference, the alignment of 16 complete plastid genomes is performed using mVISTA (Figure 2). Overall, sequence divergence is low across the Fagaceae plastid genomes. Among them, F. engleriana shows marked differences compared with other species. As expected, IRs and coding regions exhibit higher conservation than SC regions and noncoding regions, respectively. For the conservation of IR regions, the substitution rates in SC regions have been detected to be several times higher than that in IR regions among diverse plants (Zhu et al., 2015), and a copy-dependent repair mechanism has been proposed to explain the lower substitution rate in IR (Perry and Wolfe, 2002). Pairwise comparisons of genetic divergence are estimated by K2p distance, ranging from 0 (Q. aliena vs. Q. aliena var. acuteserrata) to 0.032 (F. engleriana vs. T. doichangensis) (Table S4). In general, low genetic divergence occurs in Fagaceae. However, when F. engleriana is included, the values of genetic divergence are always high (vary from 0.029 to 0.032). T. doichangensis is another taxon that shows relatively high genetic divergence (approximately 0.007). Interestingly, the infrageneric divergence in Quercus (ranges from 0.001 to 0.005) is comparable to that of inter-generic differentiation in Fagaceae (e.g., distance between Lithocarpus and Castanopsis is 0.004, distance between Castanopsis and Castanea is 0.003).

Figure 2.

Sequence identity plot comparing the 16 Fagaceae plastid genomes with Q. rubra as a reference. The y-axis represents % identity ranging from 50 to 100%. Coding and noncoding regions are marked in purple and pink, respectively.

Fagaceae phylogeny

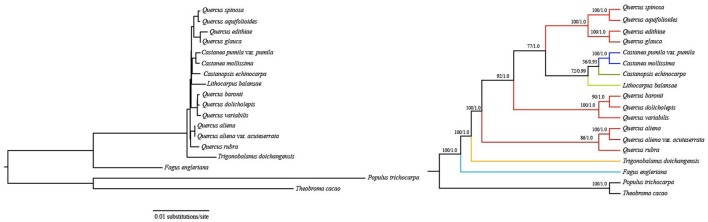

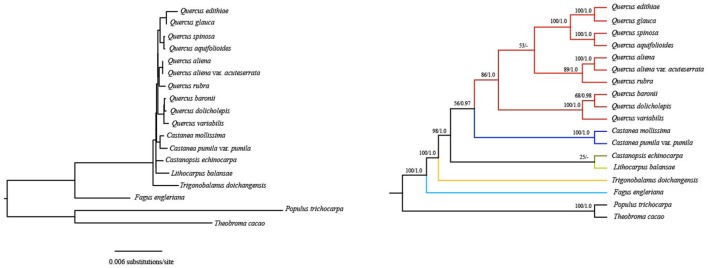

Different analysis methods (BI and ML analyses) yield largely identical phylogenetic trees from each dataset [76 shared protein-coding genes, codon positions 1 + 2, codon position 3, and five functional categories of protein-coding genes (Table 5)]. The aligned length and used model of each dataset are shown in Table 6. The aligned sequences of the first three datasets are shown in Supplemental Data Sheet 1.

Table 5.

List of the 76 common protein-coding genes divided into five functional groups.

| Protein-coding gene category | Genes |

|---|---|

| Gene expression | rps2, rps14, rps4, rps18, rps12, rps11, rps8, rps3, rps19, rps7, rps15, rps7, rpl33, rpl20, rpl36, rpl14, rpl16, rpl2, rpl23 (*2), rpoC2, rpoC1, rpoB, rpoA |

| Photosynthetic apparatus | psbA, psbK, psbI, psbM, psbD, psbC, psbJ, psbL, psbF, psbE, psbB, psbT, psbN, psbH, psaB, psaA, psaI, psaJ, psaC, petN, petA, petL, petB, petD, ycf3, ycf4, accD |

| Photosynthetic metabolism | atpA, atpF, atpH, atpI, atpE, atpB, rbcL, ndhJ, ndhK, ndhC, ndhB (*2), ndhF, ndhD, ndhE, ndhG, ndhI, ndhA, ndhH |

| Miscellaneous | matK, cemA, clpP, ccsA |

| Unknown | ycf2 (*2) |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the genes duplicated in the IR regions.

Table 6.

Sites and models in ML and BI analyses for each dataset.

| Dataset | Number of sites | Model in ML | Model in BI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 76 common protein-coding genes | 72,235 | GTR+G | GTR+I+G |

| Codon positions 1 + 2 | 48,176 | GTR+G | TVM+I+G |

| Codon position 3 | 24,353 | GTR+G | GTR+G |

| Gene expression | 18,856 | GTR+G | GTR+I+G |

| Photosynthetic apparatus | 16,970 | GTR+G | GTR+G |

| Photosynthetic metabolism | 18,817 | GTR+G | TVM+I+G |

| Miscellaneous | 3,786 | GTR+G | TVM+G |

| Unknown | 13,914 | GTR+G | GTR |

Support is generally high for almost all relationships inferred from 76 common protein-coding genes (the support values have a range of 72/0.99–100/1.0, except for a node with 56/0.93 support) (Figure 3). F. engleriana is in the basal position, followed by T. doichangensis. Lithocarpus balansae is sister to a clade of (Castanopsis echinocarpa, C. mollissima, Castanea pumila var. pumila). It is noteworthy that species in the genus Quercus do not form a clade. The 3rd codon site dataset and five functional groups of protein-coding genes datasets exhibit partly congruent versions compared with the above topology (Figures S1–S6). Differences mainly include the positions of groups in Quercus and the corresponding nodes obtain weak-to-moderate support (support values are generally < 50/0.50). Moreover, the topologies of species in a group (such as in Quercus) or in a genus (such as Castanea) are identical in almost all analyses and receive strong support.

Figure 3.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of 76 protein-coding genes. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node.

Notably, phylogenetic relationships derived from the first two codon sites dataset are completely recovered with generally strong support and all oaks form a clade with high support (86% bootstrap values and 1.0 posterior probabilities) (Figure 4). These Quercus species are divided into two clades. The first clade split into two subclades: one shows that Q. rubra is sister to Q. aliena and Q. aliena var. acuteserrata; the other shows that Q. baronii appears to be more closely related to Q. dolicholepis than to Q. variabilis. The second clade is composed of group Cyclobalanopsis (according to Denk and Grimm, 2010) (Q. glauca and Q. edithiae) and species Q. spinosa and Q. aquifolioides. Overall, the topology of other clades (genus Fagus, Trigonobalanus, Lithocarpus, and Castanopsis) is nearly identical to those based on two nuclear loci (ITS and CRC) (Oh and Manos, 2008), except for the placement of Castanea as sister to Quercus vs. Castanopsis.

Figure 4.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of the first two codon positions of protein-coding genes. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Discussion

Plastid sequence evolution

In general, the size, gene content and gene order are similar among the plastid genomes, which reveal that plastid genomes are highly conserved in Fagaceae. Moreover, gene loss occurs in Fagaceae (Table S1). From the result of alignment, we find that the lost protein-coding genes are caused by annotation error in most cases (e.g., the lost protein-coding genes ycf1, rpl2, rpl22, petG). Firstly, the sequences that encode the lost genes not only possess proper initial and termination codons, but also present highly conserved content compared with other species. Furthermore, the protein-coding gene loss only occurs in one or two species, whereas the corresponding protein-coding genes always exist in the other species.

IR contraction and expansion is a common evolutionary phenomenon (Kim and Lee, 2004; Hansen et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008; Davis and Soreng, 2010; Huang et al., 2014) and may cause variation in length of angiosperm plastid genome (Kim and Lee, 2004). The slight differences of IR/SC boundary regions in Fagaceae may be the result of IR contraction/expansion. Moreover, the minor IR boundary shifts of Fagaceae plastomes have neither triggered the transfer of genes between SC regions and IR regions or the gain/loss of genes, which have been detected in some plant lineages (Zhu et al., 2015, and references therein).

Codon usage bias is an important evolutionary phenomenon. GC content is the major factor in shaping the biased codon usage and could play an important role during the evolution of genomic structure (e.g., thermostability and modulation of replication, transcription and translation) (Sueoka and Kawanishi, 2000; Bellgard et al., 2001, and references therein). The observation of GC content level indicates that plastid genome in Fagaceae are AT-rich and there is a strong bias toward A/T at the third codon position, which are consistent with previous plastid genome studies (e.g., Shimada and Sugiuro, 1991; Clegg et al., 1994; Tangphatsornruang et al., 2009; Delannoy et al., 2011). The presence of translation-preferred codons may be the result of both natural selection and mutation preference during the plastid genome evolutionary process. Variations in codon bias are highly similar in all analyzed species, which also suggests that Fagaceae plastid genomes are highly conserved.

Larger and more complex repeat sequences may play an important role in the rearrangement of plastid genomes and sequence divergence (Timme et al., 2007; Weng et al., 2013); therefore, we investigated the numbers and distributions of tandem, dispersed, and palindromic repeats. We find that repeats in different species are usually located in the same genes (ycf1 and ycf2), or genes with similar functions (e.g., psaB/psaA, trnS-GCU/trnS-UGA, trnG-GCC/trnG-UCC, and trnS-UGA/trnS-GGA). Moreover, longer repeats are rare in Fagaceae plastomes (6 of the 440 repeats are longer than 40 bp) compared with some other plant lineages (Zhang et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2014; Cai et al., 2015)

Overall, low genetic divergence occurs in Fagaceae. Fagus represents an early diverged group in Fagaceae (Manos et al., 2001), which may result in relatively high genetic divergence between F. engleriana and other species. The infrageneric divergence in Quercus is comparable to that of inter-generic differentiation in Fagaceae, which was also observed in the studies of Simeone et al. (2016) and Vitelli et al. (2017). As a widely distributed genus, the relatively high inter-specific variation in Quercus may be related to the local adaptation to different environments. Recently, adaptive genetic variation of several climate-associated genes in oaks have been detected (Sork et al., 2015; Rellstab et al., 2016).

Fagaceae phylogeny and the effects of codon composition bias and gene function

The phylogenetic tree based on the 76 shared protein-coding genes receives generally strong support. The closer relationships among genera Lithocarpus, Castanopsis, and Castanea in this study support the taxonomic treatment of insect-pollinated subfamily Castaneoideae, including Chrysolepis, Lithocarpus, Castanopsis, and Castanea (Nixon, 1989; Oh and Manos, 2008). Notably, genus Quercus has always been resolved as monophyletic in the previous nuclear phylogenies (Oh and Manos, 2008; Denk and Grimm, 2010; Hubert et al., 2014), however, infragenetic groups of Quercus do not form one clade in this study (Figure 3). This phenomenon was also observed in previous molecular phylogenies (e.g., Manos et al., 2008; Simeone et al., 2016). In sum, resemblance between nuclear gene tree and plastid tree of genus Quercus is lost. Beside the possible reasons mentioned in the introduction (e.g., chloroplast capture, incomplete lineage sorting, and different evolutionary histories of plastid and nucleus), the complex evolutionary history of oaks (Jiménez et al., 2004; Grivet et al., 2006) may also be taken into account.

While the 76 common protein-coding genes dataset generates a highly supported phylogeny, the inference may be an artifact when considering the topology of the genus Quercus as inferred from nuclear genes and pollen morphology (Oh and Manos, 2008; Denk and Grimm, 2009, 2010). Thus, we further evaluated the impact of codon composition bias and gene function, which may have influence on topological structure. Phylogenetic trees derived from the third codon position and five functional categories of protein-coding genes not only fail to resolve all oaks as one clade, but also show conflicting relationships in some clades (with weak-to-moderate support). For the third codon position, so much change has occurred at these sites as they are near neutral (Sueoka, 1988). Thus, the biased inference may be attributed to less historically accurate information provided by these sites (Cox et al., 2014). From the results of the phylogenetic trees based on different gene function datasets, we concluded that a relatively small number of plastid genes did not provide sufficient phylogenetic signal to explore the relationships in this complex and long-lived woody plants. In other words, gene function is not the determining factor that influences Fagaceae phylogenetic inference. Moreover, we also used RY recoding (A and G = R, C and T = Y) to analyze the 76 shared protein-coding genes. However, the recovered tree was not better than the trees obtained on the original dataset or with codon positions 1+2. In particular, the genus Quercus was not monophyletic (data not shown).

Using the first two codon sites dataset, relationships are completely recovered with generally strong support and all oaks form one clade, which is compatible with the more plausible nuclear phylogeny (Oh and Manos, 2008). The first and second codon positions are subject to functional constraints against non-synonymous mutation, because mutations at these positions usually lead to amino acid change. For many phylogenetic analyses, it is common to eliminate the third codon position considering the effect of composition bias (Goremykin et al., 2003; Gibson et al., 2005; Cox et al., 2014). In the phylogenetic tree generated from the dataset considering only the first and second codon sites, F. engleriana is the first to diverge, followed by T. doichangensis, which indicates that they are early-diverging taxa in Fagaceae. This is in agreement with the recent discovery of the oldest known Fagus remains from ca. 60 Ma old sedimentary rocks of western Greenland (Grímsson et al., 2016). Although the phylogenetic tree yields a sister relationship between genus Castanea and genus Quercus, the support values of the node are poor (56% bootstrap value). Thus, we do not conclude that Castanea appears to be more closely related to Quercus than to Castanopsis. Overall, all of the relationships among these genera are nearly identical to those inferred from nuclear data (Oh and Manos, 2008; Denk and Grimm, 2010). In the genus Quercus, based on pollen characteristics and nuclear markers, six major intrageneric groups (Cyclobalanopsis, Cerris, Ilex, Lobatae, Protobalanus, and Quercus) have been identified (Oh and Manos, 2008; Denk and Grimm, 2009, 2010; Hubert et al., 2014). Relationships among Q. rubra, Q. aliena, Q. aliena var. acuteserrata, Q. baronii, Q. dolicholepis, and Q. variabilis in the current study are identical to that in Yang et al. (2016), which were inferred from complete plastid genome sequences and different plastid genome regions (LSC+SSC+IRB, LSC+SSC, LSC, SSC). However, the positions of Q. spinosa and Q. aquifolioides were either unresolved or poorly supported in Yang et al. (2016). Herein, the two species always form a well-supported monophyletic clade and then cluster with group Cyclobalanopsis. Q. baronii, Q. dolicholepis, Q. spinosa and Q. aquifolioides are regarded as members of group Ilex in earlier studies (Denk and Grimm, 2009, 2010; Simeone et al., 2013; Denk and Tekleva, 2014; Hubert et al., 2014), while they do not cluster together in this phylogenetic tree. Q. baronii and Q. dolicholepis appear more closely related to Q. variabilis, which belongs to group Cerris. Based on nuclear genes or plastid markers, Asian species (e.g., Q. pseudosemicarpifolia, Q. semecarpifolia, Q. franchetii sampled from China) in group Ilex were always embedded in group Cerris (Simeone et al., 2013, 2016; Hubert et al., 2014). It is possible that incomplete lineage sorting and introgression cause this scenario. In another cluster, Q. rubra shows closer relationship to Q. aliena and Q. aliena var. acuteserrata (sampled from China). Group Lobatae occurs in New World only and group Quercus occurs both in the Old and New World; the ancestral area of these two groups is North America with dispersal to Asia and then Europe, which may contribute to the widespread distribution of group Quercus (Manos and Stanford, 2001). Previous molecular studies demonstrated that there was generally low genetic differentiation between North American and Eurasian members of group Quercus (Manos et al., 2001; Denk and Grimm, 2010). There were generally closer relationships among New World groups (Lobatae, Protobalanus, and Quercus) based on pollen characteristics and molecular markers, as we found in our study. Certainly, it would be necessary to sample more species to explore the phylogenetic relationships of Quercus in future.

Author contributions

YY and GZ: designed the experiments; YY, JZ, LF, TZ, GB, and JY: performed the experiments and analyzed the data; YY: wrote the paper; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Min Deng, Jia Li at Chenshan Botanical Garden and Haijia Chu at Wuhan Botanical Garden for assistance collecting materials. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31770229).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00082/full#supplementary-material

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of the third codon position of protein-coding genes. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to gene expression functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to photosynthetic apparatus functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to photosynthetic metabolism functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to miscellaneous functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to unknown functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Gene differences compared with Quercus baronii.

Summary of average relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of the codon usage in the Fagaceae cp genomes. AA, Amino acid; Fe, F. engleriana; Td, T. doichangensis; Qr, Q. rubra; Qs, Q. spinosa; Qa, Q. aquifolioides; Qb, Q. baronii; Qal, Q. aliena; Qala, Q. aliena var. acuteserrata; Qv, Q. variabilis; Qd, Q. dolicholepis; Qg, Q. glauca; Qe, Q. edithiae; Ce, C. echinocarpa; Lb, L. balansae; Cm, C. mollissima; Cp, C. pumila var. pumila.

Repeats distribution.

Protein-coding sequence divergence (K2p) in Fagaceae.

References

- Alexander L. W., Woeste K. E. (2014). Pyrosequencing of the northern red oak (Quercus rubra L.) chloroplast genome reveals high quality polymorphisms for population management. Tree Genet. Genomes 10, 803–812. 10.1007/s11295-013-0681-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett C. F., Baker W. J., Comer J. R., Conran J. G., Lahmeyer S. C., Leebens-Mack J. H., et al. (2016). Plastid genomes reveal support for deep phylogenetic relationships and extensive rate variation among palms and other commelinid monocots. New Phytol. 209, 855–870. 10.1111/nph.13617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett C. F., Davis J. I., Leebens-Mack J., Conran J. G., Stevenson D. W. (2013). Plastid genomes and deep relationships among the commelinid monocot angiosperms. Cladistics 29, 65–87. 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellgard M., Schibeci D., Trifonov E., Gojobori T. (2001). Early detection of G + C differences in bacterial species inferred from the comparative analysis of the two completely sequenced Helicobacter pylori strains. J. Mol. Evol. 53, 465–468. 10.1007/s002390010236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. (1999). Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucl. Acids Res. 27:573. 10.1093/nar/27.2.573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birky C. W., Maruyama T., Fuerst P. (1983). An approach to population and evolutionary genetic theory for genes in mitochondria and chloroplasts, and some results. Genetics 103, 513–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Ma P. F., Li H. T., Li D. Z. (2015). Complete plastid genome sequencing of four Tilia species (Malvaceae): a comparative analysis and phylogenetic implications. PLoS ONE 10:e0142705. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Guisinger M., Kim H. G., Ruck E., Blazier J. C., McMurtry V., et al. (2008). Extensive reorganization of the plastid genome of Trifolium subterraneum (Fabaceae) is associated with numerous repeated sequences and novel DNA insertions. J. Mol. Evol. 67, 696–704. 10.1007/s00239-008-9180-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell-Caballero J., Alonso R., Ibañez V., Terol J., Talon M., Dopazo J. (2015). A phylogenetic analysis of 34 chloroplast genomes elucidates the relationships between wild and domestic species within the genus Citrus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 2015–2035. 10.1093/molbev/msv082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavender-Bares J., Ackerly D. D., Baum D. A., Bazzaz F. A. (2004). Phylogenetic overdispersion in Floridian oak communities. Am. Nat. 163, 823–843. 10.1086/386375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. C., Lin H. C., Lin I. P., Chow T. Y., Chen H. H., Chen W. H., et al. (2006). The chloroplast genome of Phalaenopsis aphrodite (Orchidaceae): comparative analysis of evolutionary rate with that of grasses and its phylogenetic implications. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 279–291. 10.1093/molbev/msj029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevreux B., Pfisterer T., Drescher B., Driesel A. J., Müller W. E., Wetter T., et al. (2004). Using the miraEST assembler for reliable and automated mRNA transcript assembly and SNP detection in sequenced ESTs. Genome Res. 14, 1147–1159. 10.1101/gr.1917404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg M. T., Gaut B. S., Learn G. H., Morton B. R. (1994). Rates and patterns of chloroplast DNA evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 6795–6801. 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosner M. E., Raubeson L. A., Jansen R. K. (2004). Chloroplast DNA rearrangements in Campanulaceae: phylogenetic utility of highly rearranged genomes. BMC Evol. Biol. 4:27. 10.1186/1471-2148-4-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C. J., Li B., Foster P. G., Embley T. M., Civán P. (2014). Conflicting phylogenies for early land plants are caused by composition biases among synonymous substitutions. Syst. Biol. 63, 272–279. 10.1093/sysbio/syt109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dane F., Wang Z., Goertzen L. (2015). Analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of Castanea pumila var. pumila, the Allegheny chinkapin. Tree Genet. Genomes 11, 1–6. 10.1007/s11295-015-0840-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. I., Soreng R. J. (2010). Migration of endpoints of two genes relative to boundaries between regions of the plastid genome in the grass family (Poaceae). Am. J. Bot. 97, 874–892. 10.3732/ajb.0900228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delannoy E., Fujii S., des Colas Francs-Small, C., Brundrett M., Small I. (2011). Rampant gene loss in the underground orchid Rhizanthella gardneri highlights evolutionary constraints on plastid genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2077–2086. 10.1093/molbev/msr028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk T., Grimm G. W. (2009). Significance of pollen characteristics for infrageneric classification and phylogeny in Quercus (Fagaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 170, 926–940. 10.1086/600134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denk T., Grimm G. W. (2010). The oaks of western Eurasia: traditional classifications and evidence from two nuclear markers. Taxon 59, 351–366. [Google Scholar]

- Denk T., Tekleva M. V. (2014). Pollen morphology and ultrastructure of Quercus with focus on group Ilex ( = Quercus subgenus Heterobalanus (Oerst.) Menitsky): implications for oak systematics and evolution. Grana 53, 255–282. 10.1080/00173134.2014.918647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. J. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer K. A., Pachter L., Poliakov A., Rubin E. M., Dubchak I. (2004). VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucl. Acids Res. 32, W273–W279. 10.1093/nar/gkh458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbany-Casals M., Unwin M., Garcia-Jacas N., Smissen R. D., Susanna A., Bayer R. J. (2014). Phylogenetic relationships in Helichrysum (Compositae: Gnaphalieae) and related genera: incongruence between nuclear and plastid phylogenies, biogeographic and morphological patterns, and implications for generic delimitation. Taxon 63, 608–624. 10.12705/633.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson A., Gowri-Shankar V., Higgs P. G., Rattray M. (2005). A comprehensive analysis of mammalian mitochondrial genome base composition and improved phylogenetic methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 251–264. 10.1093/molbev/msi012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goremykin V. V., Hirsch-Ernst K. I., Wölfl S., Hellwig F. H. (2003). Analysis of the Amborella trichopoda chloroplast genome sequence suggests that Amborella is not a basal angiosperm. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 1499–1505. 10.1093/molbev/msg159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grímsson F., Grimm G. W., Zetter R., Denk T. (2016). Cretaceous and paleogene fagaceae from North America and Greenland: evidence for a Late Cretaceous split between Fagus and the remaining Fagaceae. Acta Palaeobotanica 56, 247–305. 10.1515/acpa-2016-0016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grímsson F., Zetter R., Grimm G. W., Pedersen G. K., Pedersen A. K., Denk T. (2015). Fagaceae pollen from the early Cenozoic of West Greenland: revisiting Engler's and Chaney's Arcto-Tertiary hypotheses. Plant Syst. Evol. 301, 809–832. 10.1007/s00606-014-1118-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivet D., Deguilloux M., Petit R. J., Sork V. L. (2006). Contrasting patterns of historical colonization in white oaks (Quercus spp.) in California and Europe. Mol. Ecol. 15, 4085–4093. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugger P. F., Cavender-Bares J. (2013). Molecular and morphological support for a Florida origin of the Cuban oak. J. Biogeogr. 40, 632–645. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02610.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guisinger M. M., Chumley T. W., Kuehl J. V., Boore J. L., Jansen R. K. (2010). Implications of the plastid genome sequence of Typha (Typhaceae, Poales) for understanding genome evolution in Poaceae. J. Mol. Evol. 70, 149–166. 10.1007/s00239-009-9317-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisinger M. M., Kuehl J. V., Boore J. L., Jansen R. K. (2011). Extreme reconfiguration of plastid genomes in the angiosperm family Geraniaceae: rearrangements, repeats, and codon usage. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 583–600. 10.1093/molbev/msq229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. K., Bhattacharyya T. K., Ghosh T. C. (2004). Synonymous codon usage in Lactococcus lactis: mutational bias versus translational selection. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 21, 527–535. 10.1080/07391102.2004.10506946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C., Bachmann L., Chevreux B. (2013). Reconstructing mitochondrial genomes directly from genomic next-generation sequencing reads - a baiting and iterative mapping approach. Nucl. Acids Res. 41, e129. 10.1093/nar/gkt371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D. R., Dastidar S. G., Cai Z., Penaflor C., Kuehl J. V., Boore J. L., et al. (2007). Phylogenetic and evolutionary implications of complete chloroplast genome sequences of four early-diverging angiosperms: Buxus (Buxaceae), Chloranthus (Chloranthaceae), Dioscorea (Dioscoreaceae), and Illicium (Schisandraceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 45, 547–563. 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Shi C., Liu Y., Mao S. Y., Gao L. Z. (2014). Thirteen Camellia chloroplast genome sequences determined by high-throughput sequencing: genome structure and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Evol. Biol. 14:151. 10.1186/1471-2148-14-151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. Y., Matzke A. J., Matzke M. (2013). Complete sequence and comparative analysis of the chloroplast genome of Coconut Palm (Cocos nucifera). PLoS ONE 8:e74736. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert F., Grimm G. W., Jousselin E., Berry V., Franc A., Kremer A. (2014). Multiple nuclear genes stabilize the phylogenetic backbone of the genus Quercus. Syst. Biodivers. 12, 405–423. 10.1080/14772000.2014.941037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R. K., Cai Z., Raubeson L. A., Daniell H., DePamphilis C. W., Leebens-Mack J., et al. (2007). Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19369–19374. 10.1073/pnas.0709121104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R. K., Raubeson L. A., Boore J. L., dePamphilis C. W., Chumley T. W., Haberle R. C., et al. (2005). Methods for obtaining and analyzing whole chloroplast genome sequences. Method Enzymol. 395, 348–384. 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)95020-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R. K., Ruhlman T. A. (2012). Plastid Genomes of Seed Plants. Dordrecht: Springer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R. K., Saski C., Lee S. B., Hansen A. K., Daniell H. (2011). Complete plastid genome sequences of three rosids (Castanea, Prunus, Theobroma): evidence for at least two independent transfers of rpl22 to the nucleus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 835–847. 10.1093/molbev/msq261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez P., de Heredia U. L., Collada C., Lorenzo Z., Gil L. (2004). High variability of chloroplast DNA in three Mediterranean evergreen oaks indicates complex evolutionary history. Heredity 93, 510–515. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling P. J. (2010). The endosymbiotic origin, diversification and fate of plastids. Philos. T. Roy. Soc. B 365, 729–748. 10.1098/rstb.2009.0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. J., Lee H. L. (2004). Complete chloroplast genome sequences from Korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res. 11, 247–261. 10.1093/dnares/11.4.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. (1980). A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16, 111–120. 10.1007/BF01731581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S., Choudhuri J. V., Ohlebusch E., Schleiermacher C., Stoye J., Giegerich R. (2001). REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucl. Acids Res. 29, 4633–4642. 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. L., Jansen R. K., Chumley T. W., Kim K. J. (2007). Gene relocations within chloroplast genomes of Jasminum and Menodora (Oleaceae) are due to multiple, overlapping inversions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1161–1180. 10.1093/molbev/msm036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Qi Z. C., Zhao Y. P., Fu C. X., Jenny Xiang Q. Y. (2012). Complete cpDNA genome sequence of Smilax china and phylogenetic placement of Liliales -influences of gene partitions and taxon sampling. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 64, 545–562. 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P. F., Zhang Y. X., Zeng C. X., Guo Z. H., Li D. Z. (2014). Chloroplast phylogenomic analysis resolve deep-level relationships of an intractable bamboo tribe Arundinarieae (Poaceae). Syst. Biol. 63, 933–950. 10.1093/sysbio/syu054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manos P. S., Cannon C. H., Oh S. H. (2008). Phylogenetic relationships and taxonomic status of the paleoendemic Fagaceae of western North America: recognition of a new genus, Notholithocarpus. Madrono 55, 181–190. 10.3120/0024-9637-55.3.181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manos P. S., Doyle J. J., Nixon K. C. (1999). Phylogeny, biogeography, and processes of molecular differentiation in Quercus subgenus Quercus (Fagaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 12, 333–349. 10.1006/mpev.1999.0614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manos P. S., Stanford A. M. (2001). The historical biogeography of Fagaceae: tracking the Tertiary history of temperate and subtropical forests of the Northern hemisphere. Int. J. Plant Sci. 162, S77–S93. 10.1086/323280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manos P. S., Zhou Z. K., Cannon C. H. (2001). Systematics of Fagaceae: phylogenetic tests of reproductive trait evolution. Int. J. Plant Sci. 162, 1361–1379. 10.1086/322949 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G. E., Rousseau-Gueutin M., Cordonnier S., Lima O., Michon-Coudouel S., Naquin D., et al. (2014). The first complete chloroplast genome of the Genistoid legume Lupinus luteus: evidence for a novel major lineage-specific rearrangement and new insights regarding plastome evolution in the legume family. Ann. Bot. 113, 1197–1210. 10.1093/aob/mcu050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J., Bell C. D., Soltis P. S., Soltis D. E. (2007). Using plastid genome-scale data to resolve enigmatic relationships among basal angiosperms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19363–19368. 10.1073/pnas.0708072104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J., Soltis P. S., Bell C. D., Burleigh J. G., Soltis D. E. (2010). Phylogenetic analysis of 83 plastid genes further resolves the early diversification of eudicots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4623–4628. 10.1073/pnas.0907801107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova S. V., Cavalieri D., Velasco R., Goremykin V. (2013). Phylogenetic analysis of 47 chloroplast genomes clarifies the contribution of wild species to the domesticated apple maternal line. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1751–1760. 10.1093/molbev/mst092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon K. C. (1989). Origins of Fagaceae, in Evolution, Systematics, and Fossil History of the Hamamelidae Vol. 2, eds Crane P. R., Blackmore S. (Oxford: Clarendon Press; ), 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. H., Manos P. S. (2008). Molecular phylogenetics and cupule evolution in Fagaceae as inferred from nuclear CRABS CLAW sequences. Taxon 57, 434–451. [Google Scholar]

- Parks M., Cronn R., Liston A. (2009). Increasing phylogenetic resolution at low taxonomic levels using massively parallel sequencing of chloroplast genomes. BMC Biol. 7:84. 10.1186/1741-7007-7-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R. K., Jain M. (2012). NGS QC Toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLoS ONE 7:e30619. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelser P. B., Kennedy A. H., Tepe E. J., Shidler J. B., Nordenstam B., Kadereit J. W., et al. (2010). Patterns and causes of incongruence between plastid and nuclear Senecioneae (Asteraceae) phylogenies. Am. J. Bot. 97, 856–873. 10.3732/ajb.0900287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escobar O. A., Balbuena J. A., Gottschling M. (2015). Rumbling orchids: how to assess divergent evolution between chloroplast endosymbionts and the nuclear host. Syst. Biol. 65, 51–65. 10.1093/sysbio/syv070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A. S., Wolfe K. H. (2002). Nucleotide substitution rates in Legume chloroplast DNA depend on the presence of the inverted repeat. J. Mol. Evol. 55, 501–508. 10.1007/s00239-002-2333-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D., Crandall K. A. (1998). Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14, 817–818. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellstab C., Zoller S., Walthert L., Lesur I., Pluess A. R., Graf R., et al. (2016). Signatures of local adaptation in candidate genes of oaks (Quercus spp.) with respect to present and future climatic conditions. Mol. Ecol. 25, 5907–5924. 10.1111/mec.13889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau-Gueutin M., Bellot S., Martin G. E., Boutte J., Chelaifa H., Lima O., et al. (2015). The chloroplast genome of the hexaploid Spartina maritima (Poaceae, Chloridoideae): comparative analyses and molecular dating. 93, 5–16. 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp P. M., Li W. H. (1986). An evolutionary perspective on synonymous codon usage in unicellular organisms. J. Mol. Evol. 24, 28–38. 10.1007/BF02099948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada H., Sugiuro M. (1991). Fine structural features of the chloroplast genome: comparison of the sequenced chloroplast genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 19, 983–995. 10.1093/nar/19.5.983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone M. C., Grimm G. W., Papini A., Vessella F., Cardoni S., Tordoni E., et al. (2016). Plastome data reveal multiple geographic origins of Quercus Group Ilex. PeerJ 4:e1897. 10.7717/peerj.1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone M. C., Piredda R., Papini A., Vessella F., Schirone B. (2013). Application of plastid and nuclear markers to DNA barcoding of Euro-Mediterranean oaks (Quercus, Fagaceae): problems, prospects and phylogenetic implications. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 172, 478–499. 10.1111/boj.12059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sork V. L., Squire K., Gugger P. F., Steele S. E., Levy E. D., Eckert A. J. (2015). Landscape genomic analysis of candidate genes for climate adaptation in a California endemic oak, Quercus lobate. Am. J. Bot. 103, 33–46. 10.3732/ajb.1500162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analysis with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegemann S., Keuthe M., Greiner S., Bock R. (2012). Horizontal transfer of chloroplast genomes between plant species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 2434–2438. 10.1073/pnas.1114076109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueoka N. (1988). Directional mutation pressure and neutral molecular evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 2653–2657. 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueoka N., Kawanishi Y. (2000). DNA G+C content of the third codon position and codon usage biases of human genes. Gene 261, 53–62. 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00480-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangphatsornruang S., Sangsrakru D., Chanprasert J., Uthaipaisanwong P., Yoocha T., Jomchai N., et al. (2009). The chloroplast genome sequence of mungbean (Vigna radiata) determined by high-throughput pyrosequencing: structural organization and phylogenetic relationships. DNA Res. 17, 11–22. 10.1093/dnares/dsp025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepe E. J., Farruggia F. T., Bohs L. (2011). A 10-gene phylogeny of Solanum section Herpystichum (Solanaceae) and a comparison of phylogenetic methods. Am. J. Bot. 98, 1356–1365. 10.3732/ajb.1000516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timme R. E., Kuehl J. V., Boore J. L., Jansen R. K. (2007). A comparative analysis of the Lactuca and Helianthus (Asteraceae) plastid genomes: identification of divergent regions and categorization of shared repeats. Am. J. Bot. 94, 302–312. 10.3732/ajb.94.3.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan G. A., DiFazio S., Jansson S., Bohlmann J., Grigoriev I., Hellsten U., et al. (2006). The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313, 1596–1604. 10.1126/science.1128691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitelli M., Vessella F., Cardoni S., Pollegioni P., Denk T., Grimm G. W., et al. (2017). Phylogeographic structuring of plastome diversity in Mediterranean oaks (Quercus Group Ilex, Fagaceae). Tree Genet. Genomes 13:3 10.1007/s11295-016-1086-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. J., Cheng C. L., Chang C. C., Wu C. L., Su T. M., Chaw S. M. (2008). Dynamics and evolution of the inverted repeat-large single copy junctions in the chloroplast genomes of monocots. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:36. 10.1186/1471-2148-8-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng M. L., Blazier J. C., Govindu M., Jansen R. K. (2013). Reconstruction of the ancestral plastid genome in Geraniaceae reveals a correlation between genome rearrangements, repeats and nucleotide substitution rates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 645–659. 10.1093/molbev/mst257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright F. (1990). The 'effective number of codons' used in a gene. Gene 87, 23–29. 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90491-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman S. K., Jansen R. K., Boore J. L. (2004). Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 20, 3252–3255. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhou T., Duan D., Yang J., Feng L., Zhao G. (2016). Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genomes of five Quercus Species. Front. Plant Sci. 7:959. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. C., Zhou T., Yang J., Meng X., Zhu J., Zhao G. (2017). The complete chloroplast genome of Quercus baronii (Quercus, L.). Mitochond. DNA 28, 290–291. 10.3109/19401736.2015.1118084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y. F., Liao W. J., Petit R. J., Zhang D. Y. (2011). Geographic variation in the structure of oak hybrid zones provides insights into the dynamics of speciation. Mol. Ecol. 20, 4995–5011. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05354.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. J., Ma P. F., Li D. Z. (2011). High-throughput sequencing of six bamboo chloroplast genomes: phylogenetic implications for temperate woody bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae). PLoS ONE 6:e20596. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu A., Guo W., Gupta S., Fan W., Mower J. P. (2015). Evolutionary dynamics of the plastid inverted repeat: the effects of expansion, contraction, and loss on substitution rates. New Phytol. 209, 1747–1756. 10.1111/nph.13743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of the third codon position of protein-coding genes. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to gene expression functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to photosynthetic apparatus functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to photosynthetic metabolism functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to miscellaneous functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Fagaceae phylogeny based on ML and BI analyses of genes belonging to unknown functional category. ML topology shown with bootstrap support values and posterior probability values listed at each node. Dash denotes nodes contradicted by the BI trees with posterior probability values < 0.50.

Gene differences compared with Quercus baronii.

Summary of average relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of the codon usage in the Fagaceae cp genomes. AA, Amino acid; Fe, F. engleriana; Td, T. doichangensis; Qr, Q. rubra; Qs, Q. spinosa; Qa, Q. aquifolioides; Qb, Q. baronii; Qal, Q. aliena; Qala, Q. aliena var. acuteserrata; Qv, Q. variabilis; Qd, Q. dolicholepis; Qg, Q. glauca; Qe, Q. edithiae; Ce, C. echinocarpa; Lb, L. balansae; Cm, C. mollissima; Cp, C. pumila var. pumila.

Repeats distribution.

Protein-coding sequence divergence (K2p) in Fagaceae.