Abstract

Objective

Research shows that active support provision is associated with greater well-being for spouses of individuals with chronic conditions. However, not all instances of support may be equally beneficial for spouses' well-being. The theory of communal responsiveness suggests that because spouses' well-being is interdependent, spouses benefit most from providing support when they believe their support increases their partner's happiness and is appreciated. Two studies tested this hypothesis.

Methods

Study 1 was a 7-day ecological momentary assessment (EMA) study of 73 spouses of persons with dementia (74%) and other conditions. In Study 1 spouses self-reported active help, perceptions of how happy the help made the partner and how much the help improved the partner's well-being, and spouses' positive and negative affect at EMA time points. Study 2 was a 7-day daily assessment study of 43 spouses of persons with chronic pain in which spouses reported their emotional support provision, perceived partner appreciation, and their own physical symptoms.

Results

Study 1 showed that active help was associated with more positive affect for spouses when the they perceived the help increased their partner's happiness and improved their partner's well-being. Study 2 showed that emotional support provision was associated with fewer spouse reported physical symptoms when perceptions of partner appreciation were high.

Conclusion

Results suggest that interventions for spouses of individuals with chronic conditions take into account spouses' perceptions of their partners' positive emotional responses. Highlighting the positive consequences of helping may increase spouses' well-being.

Keywords: Helping Behavior, Daily Affect, Marriage

A vast literature shows that providing help to others has psychological and physical benefits for helpers across laboratory and community settings (Brown & Brown, 2015; Morelli, Lee, Arnn, & Zaki, 2015). Yet, this phenomenon is often debated in literature examining the well-being of spouses who have partners with chronic conditions (Schulz & Monin, 2012). While other aspects of having a partner with a chronic condition, such as witnessing suffering, can be emotionally difficult (Monin & Schulz, 2009), providing active help to the partner predicts greater daily positive affect for the spouse (Poulin et al., 2010). The aim of this research was to examine whether certain relational conditions – perceiving that help increases the partner's happiness and that the help is appreciated -- maximize the positive effects of helping on spouses' daily well-being. Understanding the interpersonal processes involved with supporting partners with chronic conditions has broad implications for how relationship functioning affects health.

Two studies tested the hypothesis that helping predicts greater well-being when a spouse perceives his or her help has positive consequences for the partner. In formulating our hypothesis, we draw from the theory of communal responsiveness as love (Clark & Mills, 1979; Clark & Monin, 2006) which states that in the course of close, communal relationships, people express their love for one another by providing care to their partner when their needs arise, with a focus on enhancing the partner's well-being. This is done in a non-contingent fashion without expectation for immediate reward. The focus is on enhancing the well-being of the partner, but the motives are not purely altruistic (Batson, 1987) as a person trusts the partner would do the same for them over the course of their relationship.

One way to examine whether spouses believe their help is improving partners' well-being, and potentially enhancing communal responsiveness, is to ask spouses about their partner's responses to help. Growing research suggests that gratitude, when perceived in social support interactions, also communicates that support is effective and that the support receiver values and desires the relationship with the support provider (Algoe, Fredrickson, & Gable, 2013). Recently, there has been a call for research to understand how gratitude functions in family support interactions (Amaro & Miller, 2016).

Here we test our hypothesis in two different contexts. Study 1 examines the psychological well-being of spouses who assist partners with at least one activity of daily living (e.g., driving, preparing meals) because of dementia or another debilitating condition. Study 2 examines the physical well-being of spouses of individuals with chronic pain.

Study 1

Study 1 tested the hypothesis that active helping is associated with greater positive and lower negative affect when the spouse perceives his or her help made the partner happy and improved the partner's well-being.

Method

Participants

Participants were providing full-time home care to an ailing marital partner in southeastern Michigan and were recruited by mailings through the Michigan Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, the Area Agency on Aging, and the local Alzheimer's Association chapter. Flyers were placed in local hospitals and senior centers, project staff gave presentations at area caregiver support groups, and word-of-mouth recruitment was encouraged. Seventy-three ‘spouses’ were recruited (for full sample details, see Poulin et al., 2010). The sample was 64% female and ranged in age from 35 to 89 (M = 71.47, SD = 10.63). About 23% of spouses had completed college; all but one were white and non-Hispanic. About 74% of partners had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease or a related dementia, 27% with a non-skin cancer, 17% with stroke, and 5% with chronic lung disease.

Procedure

At home visits, spouses completed a baseline survey and were trained in using Palm Pilots for ecological momentary assessment (EMA; (Stone, Shiffman, & DeVries, 1999). During the next 7 days, spouses carried the Palm Pilots, programmed to beep at random (approximately three-hour) intervals during waking hours to ask questions about the prior interval. Each set of questions required 1-3 minutes. Beeps occurred approximately 5 times a day, for a total of about 15 minutes per day. Across the study, spouses could complete up to 35 EMAs. On average, spouses completed 22.75 (SD = 10.68). Completion rates were not associated with age, gender, or baseline number of chronic spouse or partner ailments (all ps > .08). Spouses could opt out of the EMA phase of the study if they found it too burdensome; none did so. The Medical Institutional Review Boards at the University of Michigan approved all procedures for this study.

Measures

Active helping time

At each EMA time point, spouses were asked, “Did you actively help your spouse at any time since the Palm Pilot last beeped?” It was explained that “active help means tasks that you might perform such as helping your spouse get across a room, cooking meals for him/her, or helping him/her with financial matters”. If they said yes, they were asked to report the amount of time spent actively helping using a five-point scale (1 = “No time,” “2 = Less than 30 minutes,” “3 = 30-50 minutes,” “4 = 1-2 hours,” 5 = “More than 2 hours”; M = 2.29, SD = 1.27). Those who said no were coded as having spent no time actively helping. In addition, the small number of time points (9 out of 1068) when spouses reporting helping, but then reported spending “no time” doing so, were coded as no time actively helping.

Perceptions of partner's response

At each EMA time point, spouses were asked how much they agreed (1 = “Disagree,” 3 = “Undecided,” 5 = “Agree”) with “Since the Palm Pilot last beeped, my help made my spouse happy” (M = 2.50, SD = 1.57), and, “… my help improved the well-being of my spouse” (M = 2.14 SD = 1.27).

Affect

At each EMA time point, spouses reported how much they were experiencing several emotions immediately before the Palm Pilot beeped using a five-point scale (1 = “Not at all,” 5 = “Very much”). A positive affect index used the mean of “happy,” “joyful,” “pleased,” and “enjoyment/fun” (M = 2.68, SD = 1.06; α = .92). A negative affect index used the mean of “depressed/blue,” “unhappy,” “frustrated,” “angry/hostile,” “worried/anxious,” “guilty,” and “stressed” (M = 1.51, SD = 0.66; α =.90).

Statistical Analysis

To test all hypotheses in Study 1 and 2, random effects modeling was used to examine the associations of spouses' help and perceptions of the partner's response with each outcome over time. All regression coefficients were estimated as the matrix-weighted average of within-and between-person effects, as implemented in Stata's xtreg random effects module, allowing within-person fluctuations across time intervals to contribute to estimates of associations among variables (StataCorp, 2014). Analyses controlled for dependent variables reported during the prior interval (i.e., in lagged form) to reduce concern regarding reverse causation. To test for moderation, each model included the product-term interaction of each indicator of perceived helping response with helping behavior. Effect sizes were estimated as the unique change in χ2 associated with a given variable, transformed as the ϕ (phi) coefficient, the magnitude of which can be interpreted in a manner similar to r (Guilford, 1954).

Results

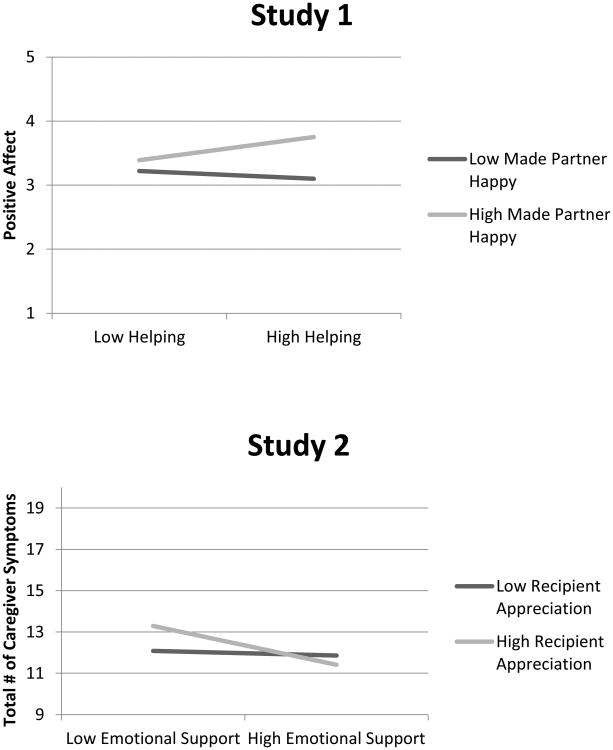

Perceptions of increasing partner happiness significantly moderated the link between helping and positive affect (B = 0.12, 95% CI [0.07, 0.16], ϕ = .17, p < .001), as did perceiving help improved partner well-being (B = 0.14, 95% CI [0.08, 0.19], ϕ = .16, p < .001). To probe these interactions, the association of helping with positive affect was examined separately for individuals 1 SD above and below the level-1 means (i.e., across all individuals and observations within individuals) on the moderator variables. Helping predicted greater positive affect for above-mean perceived levels of increasing partner happiness (B = 0.18, 95% CI [0.11, 0.25], ϕ = .17, p < .001) and improving partner well-being (B = 0.20, 95% CI [0.12, 0.28], ϕ = .16, p < .001) but did not -- or did the opposite-- for below-mean levels of increasing partner happiness (B = -0.06, 95% CI [-0.12, 0.01], ϕ = .06, p = .08) and improving partner well-being (B = -0.08, 95% CI [-0.14, -0.01], ϕ = .07, p = .03). Patterns were similar for both interactions (see Figure 1). Effects were not significant for negative affect (partner happiness: B = 0.004, 95% CI [-0.02, 0.02], ϕ < .01, p = .68; partner well-being: B = -0.02, 95% CI [-0.05, 0.002], ϕ = .06, p = .07).)

Figure 1.

Study 1: The association between helping time and positive affect for perceiving that help increased partner happiness +/-1 SD of the mean. Study 2: The association between emotional support provision and physical symptoms for perceived partner appreciation +/-1 SD of the mean.

Note. Study 1: The total range of the positive affect scale was 1 to 5. High and low values of helping are also 1 SD above and below the mean. Study 2: The total range of symptoms was 9 to 20. High and low values of emotional support provision are also 1 SD above and below the mean.

Study 2

Study 2 examined whether perceived partner appreciation moderated the link between spouses' emotional support provision and spouse reported physical well-being in daily life.

Method

Participants

Spouses and their partner with a self-reported musculoskeletal condition (i.e., osteoarthritis, lower back pain) were recruited from newspaper advertisements and flyers in the New Haven, CT region for a larger study examining interpersonal emotion regulation in older couples with pain. Spouses had to (a) be older than 50 years; (b) be married or in a marriage-like relationship living together; and (c) experience less pain on average than the partner with the musculoskeletal condition. Forty-three spouses completed (5+ days) of data. Spouses ranged in age from 54 to 81 (M = 65.78, SD = 5.83), and 56% were women. See Monin, et al (2015) for more sample details. Yale University's Human Subjects Committee approved this study.

Procedure

The diary study occurred after a laboratory session that involved tasks examining spouses' reactions to their partner's suffering (Monin, Levy, & Kane, 2015). Participants were given a paper daily diary survey to take home. For the next 7 days, starting the following evening, a research assistant administered the daily diary survey over the phone. The interview times ranged from 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. to allow flexibility with the participants' schedules.

Measures

Emotional support provision

Spouses were asked to indicate how often they did any of the following each day: “Listened to your partner talk about how he/she was feeling”, “Showed your partner affection to comfort him/her”, and “Encouraged your partner when he/she was completing tasks” on a scale from 1 (rarely to none of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time). A mean score was calculated (M = 2.68, SD = 0.95, α = .86).

Perceived appreciation

The spouse was asked how much the partner showed appreciation for each of the emotional support items described above on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). A mean score was calculated (M = 2.77, SD = 0.92, α = .89).

Physical health symptoms

Spouses were asked how often they felt nine symptoms each day (pain, dry mouth, nausea, difficulty sleeping, lack of appetite, shortness of breath, constipation/diarrhea, confusion/difficulty concentrating) on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very often; Schulz et al., 2010). A symptom count (M = 11.82, SD = 2.84) was calculated.

Results

Perceived appreciation significantly moderated the association between emotional support provision and symptom total (B = -0.42, 95% CI [-0.64, -0.19], ϕ = .27, p < .001). Provision of emotional support predicted decreased symptoms at above-mean perceived levels of appreciation (B = -0.79, 95% CI [-1.18, -0.41], ϕ = .29, p < .001), but not at below-mean perceived levels of appreciation (B = -0.02, 95% CI [-0.41, 0.37], ϕ = .14, p = .91; see Figure 1).

General Discussion

These studies showed that spouses of partners with chronic conditions feel happier and report less physical health symptoms when spouses believe their help is appreciated in daily life. Our findings support the theory of communal responsiveness as love (Clark & Monin, 2006) as well as a functional perspective on gratitude expression (Algoe et al., 2013). Clinically, this work suggests that interventions for spouses with partners with chronic conditions consider the spouses' perceptions of how daily acts of support make their partners feel. Perceiving that a loved one appreciates help likely signals to the spouse that he or she is in a mutually responsive relationship. These findings may have substantial clinical significance: the effect size for the moderating role of perceived appreciation (range: .16 - .27) meets or exceeds those reported in a recent JAMA review of current psychosocial (range: .09 - .23) or pharmacologic interventions (.18 - .27) for caregiver burden (Adelman, Tmanova, Delgado, Dion, & Lachs, 2014). Although this study is limited by only capturing the spouse's perspective, spouses' perceptions of responsiveness are often more important than partner reports for psychological well-being in close relationships (Lemay, Clark, & Feeney, 2007), and the findings further support the need for couple oriented interventions in the context of chronic conditions and disability (Martire, 2013).

We also found that providing help was associated with lower positive affect when help was not seen as improving the partner's well-being. It may have been that this help was mundane, burdensome, or unenjoyable (e.g. chores; Freedman, Cornman, & Carr, 2014), given in an obligatory fashion (Schulz et al., 2012), was not welcomed (Martire, Stephens, Druley, & Wojno, 2002), or that help was not enough to relieve partner suffering (Monin & Schulz, 2009).

Our findings also showed that spouses' daily help, emotional support specifically, was associated with spouses reporting fewer physical symptoms when perceptions of partner appreciation were high. This may reflect that spouses who perceive their partners as appreciative feel less stressed in their role as a support provider and perhaps more mutually supported by their partner. It may also reflect that spouses who feel healthier are more emotionally available to their partners. It is interesting to note that symptoms were greatest when spouses gave low levels of emotional support but the support was highly appreciated. Emotional support from spouses who report more symptoms may be less expected and thus more appreciated. More research is needed that acknowledges the health of both couple members and the effects on mutual care processes among married couples in which one or both members suffer from chronic conditions.

Taken together, this study provides evidence that active helping relates to greater spouse well-being when spouses believe they are improving their partner's happiness and when they feel appreciated. Importantly, this study adds to a growing body of evidence showing that it is important to target emotional communication between spouses in daily support interactions to improve psychological well-being in the context of chronic conditions and disability.

Acknowledgments

Study 1 was supported by a Paul Beeson Physician Faculty Scholars in Aging Research award, the Michigan Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (P50 AG08671), and the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG019180) to Dr. Kenneth M. Langa. The authors would like to express their gratitude to Sara Hoerauf and Elli Georgal for recruitment of Study 1 participants and data collection, and to Samuel Kaufman for preparation of data files. Study 2 was supported by career development awards to Joan Monin from the NIA (K01 AG042450) and the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale (P30 AG21342).

Contributor Information

Joan K. Monin, Yale School of Public Health

Michael J. Poulin, University at Buffalo

Stephanie L. Brown, Stony Brook University

Kenneth M. Langa, University of Michigan and Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Center for Clinical Management Research

References

- Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:1052–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algoe S, Fredrickson BL, Gable SL. The social functions of the emotion of gratitude via expression. Emotion. 2013;13(4):605–609. doi: 10.1037/a0032701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro L, Miller K. Discussion of care, contribution, and perceived (in) gratitude in the family caregiver and sibling relationship. Personal Relationships. 2016;23:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD. Prosocial Motivation: Is it ever Truly Altruistic? In: Leonard B, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 20. Academic Press; 1987. pp. 65–122. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Brown R. Connecting prosocial behavior to improved physical health: Contributions from the neurobiology of parenting. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2015;55:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Mills J. Interpersonal attraction in exchange and communal relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37(1):12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Monin JK. Giving and receiving communal responsiveness as love. In: Weis RJSK, editor. The new psychology of love. 2nd. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2006. pp. 200–221. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, Cornman JC, Carr D. Is spousal caregiving associated with enhanced well-being? New evidence from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2014;69(6):861–869. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilford JP. Psychometric methods. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Lemay EP, Jr, Clark MS, Feeney BC. Projection of responsiveness to needs and the construction of satisfying communal relationships. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2007;92(5):834. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire L. Couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness: Where do we go from here? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2013;30(2):207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Martire L, Stephens M, Druley JA, Wojno W. Negative reactions to received spousal care: predictors and consequences of miscarried support. Health Psychology. 2002;21(2):167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin JK, Levy BR, Kane HS. To love is to suffer: Older adults' daily emotional contagion to perceived spousal suffering. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2015 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin, Schulz R. Interpersonal effects of suffering in older adult caregiving relationships. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24(3):681–695. doi: 10.1037/a0016355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli SA, Lee IA, Arnn ME, Zaki J. Emotional and instrumental support provision interact to predict well-being. Emotion. 2015;15(4):484–493. doi: 10.1037/emo0000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance on Caregiving. Caregiving in the US. Bethesda, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin, Brown SL, Ubel PA, Smith DM, Jankovic A, Langa KM. Does a helping hand mean a heavy heart? Helping behavior and well-being among spouse caregivers. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25(1):108–117. doi: 10.1037/a0018064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR, Cook TB, Martire LM, Tomlinson JM, Monin JK. Predictors and consequences of perceived lack of choice in becoming an informal caregiver. Aging & Mental Health. 2012;16(6):712–721. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.651439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Monin JK. The costs and benefits of caregiving. In: Brown, Brown, Penner, editors. Moving beyond self interest: Perspectives from evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and the social sciences. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Monin JK, Czaja SJ, Lingler JH, Beach SR, Martire LM, et al. Cook TB. Measuring the experience and perception of suffering. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(6):774–784. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp L. Stata 13. College Station: StataCorp LP; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman SS, DeVries MW. Ecological momentary assessment. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russel Sage; 1999. pp. 26–39. [Google Scholar]