Abstract

Background

In the absence of horizontal gene transfer it is possible to reconstruct the history of gene families from empirically determined orthology relations, which are equivalent to event-labeled gene trees. Knowledge of the event labels considerably simplifies the problem of reconciling a gene tree T with a species trees S, relative to the reconciliation problem without prior knowledge of the event types. It is well-known that optimal reconciliations in the unlabeled case may violate time-consistency and thus are not biologically feasible. Here we investigate the mathematical structure of the event labeled reconciliation problem with horizontal transfer.

Results

We investigate the issue of time-consistency for the event-labeled version of the reconciliation problem, provide a convenient axiomatic framework, and derive a complete characterization of time-consistent reconciliations. This characterization depends on certain weak conditions on the event-labeled gene trees that reflect conditions under which evolutionary events are observable at least in principle. We give an -time algorithm to decide whether a time-consistent reconciliation map exists. It does not require the construction of explicit timing maps, but relies entirely on the comparably easy task of checking whether a small auxiliary graph is acyclic. The algorithms are implemented in C++ using the boost graph library and are freely available at https://github.com/Nojgaard/tc-recon.

Significance

The combinatorial characterization of time consistency and thus biologically feasible reconciliation is an important step towards the inference of gene family histories with horizontal transfer from orthology data, i.e., without presupposed gene and species trees. The fast algorithm to decide time consistency is useful in a broader context because it constitutes an attractive component for all tools that address tree reconciliation problems.

Keywords: Tree reconciliation, Horizontal gene transfer, Reconciliation map, Time-consistency, History of gene families

Background

Modern molecular biology describes the evolution of species in terms of the evolution of the genes that collectively form an organism’s genome. In this picture, genes are viewed as atomic units whose evolutionary history by definition forms a tree. The phylogeny of species also forms a tree. This species tree is either interpreted as a consensus of the gene trees or it is inferred from other data. An interesting formal manner to define a species tree independent of genes and genetic data is discussed, e.g. in [1].

In this contribution, we assume that gene and species trees are given independently of each other. The relationship between gene and species evolution is therefore given by a reconciliation map that describes how the gene tree is embedded in the species tree: after all, genes reside in organisms, and thus at each point in time can be assigned to a species.

From a formal point of view, a reconciliation map identifies vertices of a gene tree with vertices and edges in the species tree in such a way that (partial) ancestor relations given by the genes are preserved by . Vertices in the species tree correspond to speciation events. By definition, in a speciation event all genes are faithfully transmitted from the parent species into both (all) daughter species. Some of the vertices in the gene tree therefore correspond to speciation events. In gene duplications, two copies of a gene are formed from a single ancestral gene and then keep residing in the same species. In horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events, the original remains within the parental species, while the offspring copy “jumps” into a different branch of the species tree. Given a gene tree with event types assigned to its interior vertices, it is customary to define pairwise relations between genes depending on the event type of their last common ancestor [2–4].

Most of the literature on this topic assumes that both the gene tree and the species tree are known but no information is available of the type of events [5–8]. The aim is then to find a mapping of the gene tree T into the species tree S and, at least implicitly, an event-labeling on the vertices of the gene tree T. Here we take a different point of view and assume that T and the types of evolutionary events on T are known. This setting has ample practical relevance because event-labeled gene trees can be derived from the pairwise orthology relation [4, 9]. These relations in turn can be estimated directly from sequence data using a variety of algorithmic approaches that are based on the pairwise best match criterion and hence do not require any a priori knowledge of the topology of either the gene tree or the species tree, see e.g. [10–13].

Genes that share a common origin (homologs) can be classified into orthologs, paralogs, and xenologs depending whether they originated by a speciation, duplication or horizontal gene transfer (HGT) event [2, 4]. Recent advances in mathematical phylogenetics [9, 14] have shown that the knowledge of these event-relations (orthologs, paralogs and xenologs) suffices to construct event-labeled gene trees and, in some case, also a species tree [3, 15, 16].

Conceptually, both the gene tree and species tree are associated with a timing of each event. Reconciliation maps must preserve this timing information because there are biologically infeasible event labeled gene trees that cannot be reconciled with any species tree. In the absence of HGT, biologically feasibility can be characterized in terms of certain triples (rooted binary trees on three leaves) that are displayed by the gene trees [16]. In the presence of HGT such triples give at least necessary conditions for a gene tree being biologically feasible [15]. In particular, the timing information must be taken into account explicitly in the presence of HGT. That is, gene trees with HGT that must be mapped to species trees only in such a way that some genes do not travel back in time.

There have been several attempts in the literature to handle this issue, see e.g. [17] for a review. In [18, 19] a single HGT adds timing constraints to a time map for a reconciliation to be found. Time-consistency is then defined as the existence of a topological order of the digraph reflecting all the time constraints. In [20] NP-hardness was shown for finding a parsimonious time-consistent reconciliation based on a definition for time-consistency that in essence considers pairs of HGTs. However, the latter definitions are explicitly designed for binary gene trees and do not apply to non-binary gene trees, which are used here to model incomplete knowledge of the exact gene phylogenies. Different algorithmic approaches for tackling time-consistency exist [17] such as the inclusion of “time-zones” known for specific evolutionary events. It is worth noting that a posteriori modifications of time-inconsistent solutions will in general violate parsimony [18]. So far, no results have become available to determine the existence of time-consistent reconciliation maps given the (undated) species tree and the event-labeled gene tree.

Here, we introduce an axiomatic framework for time-consistent reconciliation maps and characterize for given event-labeled gene trees T and species trees S whether there exists a time-consistent reconciliation map. We provide an -time algorithm that constructs a time-consistent reconciliation map if one exists.

Notation and preliminaries

We consider rooted trees with root and leaf set . A vertex is called a descendant of , , and u is an ancestor of v, , if u lies on the path from to v. As usual, we write and to mean and . The partial order is known as the ancestor order of T; the root is the unique maximal element w.r.t . If or then u and v are comparable and otherwise, incomparable. We consider edges of rooted trees to be directed away from the root, that is, the notation for edges (u, v) of a tree is chosen such that . If (u, v) is an edge in T, then u is called parent of v and v child of u. It will be convenient for the discussion below to extend the ancestor relation on V to the union of the edge and vertex sets of T. More precisely, for the edge we put if and only if and if and only if . For edges and in T we put if and only if . For , we write for the set of leaves in the subtree T(x) of T rooted in x.

For a non-empty subset of leaves , we define , or the least common ancestor of A, to be the unique -minimal vertex of T that is an ancestor of every vertex in A. In case , we put . We have in particular for all . We will also frequently use that for any two non-empty vertex sets A, B of a tree, it holds that .

A phylogenetic tree is a rooted tree such that no interior vertex in has degree two, except possibly the root. If corresponds to a set of genes or species , we call a phylogenetic tree on gene tree or species tree, respectively. In this contribution we will not restrict the gene or species trees to be binary, although this assumption is made implicitly or explicitly in much of the literature on the topic. The more general setting allows us to model incomplete knowledge of the exact gene or species phylogenies. Of course, all mathematical results proved here also hold for the special case of binary phylogenetic trees.

In our setting a gene tree on is equipped with an event-labeling map with that assigns to each interior vertex v of T a value indicating whether v is a speciation event (), duplication event () or HGT event (). It is convenient to use the special label for the leaves x of T. Moreover, to each edge e a value is added that indicates whether e is a transfer edge (1) or not (0). Note, only edges (x, y) for which might be labeled as transfer edge. We write for the set of transfer edges in T. We assume here that all edges labeled “0” transmit the genetic material vertically, that is, from an ancestral species to its descendants.

We remark that the restriction of t to the vertex set V coincides with the “symbolic dating maps” introduced in [21]; these have a close relationship with cographs [14, 22, 23]. Furthermore, there is a map that assigns to each gene the species in which it resides. The set , , is the set of species from which the genes M are taken. We write for the gene tree with event-labeling t and corresponding map .

Removal of the transfer edges from yields a forest that inherits the ancestor order on its connected components, i.e., iff and x, y are in same subtree of [20]. Clearly uniquely defines a root for each subtree and the set of descendant leaf nodes .

In order to account for duplication events that occurred before the first speciation event, we need to add an extra vertex and an extra edge “above” the last common ancestor of all species in the species tree . Hence, we add an additional vertex to V (that is now the new root of S) and the additional edge to E. Strictly speaking S is not a phylogenetic tree in the usual sense, however, it will be convenient to work with these augmented trees. For simplicity, we omit drawing the augmenting edge in our examples.

Observable scenarios

The true history of a gene family, as it is considered here, is an arbitrary sequence of speciation, duplication, HGT, and gene loss events. The applications we envision for the theory developed, here, however assume that the gene tree and its event labels are inferred from (sequence) data, i.e., is restricted to those labeled trees that can be constructed at least in principle from observable data. The issue here are gene losses that may completely eradicate the information on parts of the history. Specifically, we require that satisfies the following three conditions:

(O1) Every internal vertex v has degree at least 3, except possibly the root which has degree at least 2.

(O2) Every HGT node has at least one transfer edge, , and at least one non-transfer edge, ;

- (O3)

- (a) If x is a speciation vertex, then there are at least two distinct children v, w of x such that the species V and W that contain v and w, resp., are incomparable in S.

- (b) If (v, w) is a transfer edge in T, then the species V and W that contain v and w, resp., are incomparable in S.

Condition (O1) ensures that every event leaves a historical trace in the sense that there are at least two children that have survived in at least two of its subtrees. If this were not the case, no evidence would be left for all but one descendant tree, i.e., we would have no evidence that event v ever happened. We note that this condition was used, e.g. in [16] for scenarios without HGT. Condition (O2) ensures that for an HGT event a historical trace remains of both the transferred and the non-transferred copy. If there is no transfer edge, we have no evidence to classify v as a HGT node. Conversely, if all edges were transfers, no evidence of the lineage of origin would be available and any reasonable inference of the gene tree from data would assume that the gene family was vertically transmitted in at least one of the lineages in which it is observed. In particular, Condition (O2) implies that for each internal vertex there is a path consisting entirely of non-transfer edges to some leaf. This excludes in particular scenarios in which a gene is transferred to a different “host” and later reverts back to descendants of the original lineage without any surviving offspring in the intermittent host lineage. Furthermore, a speciation vertex x cannot be observed from data if it does not “separate” lineages, that is, there are two leaf descendants of distinct children of x that are in distinct species. However, here we only assume to have the weaker Condition (O3.a) which ensures that any “observable” speciation vertex x separates at least locally two lineages. In other words, if all children of x would be contained in species that are comparable in S or, equivalently, in the same lineage of S, then there is no clear historical trace that justifies x to be a speciation vertex. In particular, most-likely there are two leaf descendants of distinct children of x that are in the same species even if only is considered. Hence, x would rather be classified as a duplication than as a speciation upon inference of the event labels from actual data. Analogously, if then v signifies the transfer event itself but w refers to the next (visible) event in the gene tree T. Given that (v, w) is a HGT-edge in the observable part, in a “true history” v is contained in a species V that transmits its genetic material (maybe along a path of transfers) to a contemporary species Z that is an ancestor of the species W containing w. Clearly, the latter allows to have which happens if the path of transfers points back to the descendant lineage of V in S. In this case the transfer edge (v, w) must be placed in the species tree such that and are comparable in S. However, then there is no evidence that this transfer ever happened, and thus v would be rather classified as speciation or duplication vertex.

Assuming that (O2) is satisfied, we obtain the following useful result:

Lemma 1

Let be the connected components of with roots , respectively. If (O2) holds, then, forms a partition of .

Proof

Since , it suffices to show that does not contain vertices of . Note, with is only possible if all edges (x, y) are removed.

Let with such that all edges (x, y) are removed. Thus, all such edges (x, y) are contained in . Therefore, every edge of the form (x, y) is a transfer edge; a contradiction to (O2).

We will show in Proposition 1 that (O1), (O2), and (O3) together imply two important properties of event labeled species trees, () and (), which play a crucial role for the results reported here.

() If , then there are distinct children v, w of x in T such that .

() If , then .

Intuitively, () is true because within a component no genetic material is exchanged between non-comparable nodes. Thus, a gene separated in a speciation event necessarily ends up in distinct species in the absence of horizontal transfer. It is important to note that we do not require the converse: does not imply , that is, the last common ancestor of two sets of genes from different species is not necessarily a speciation vertex.

Now consider a transfer edge , i.e., . Then and are subtrees of distinct connected components of . Since HGT amounts to the transfer of genetic material across distinct species, the genes v and w must be contained in distinct species X and Y, respectively. Since no genetic material is transferred between contemporary species and in , where and is a descendant of X and Y, respectively we derive ().

Proposition 1

Conditions (O1)–(O3) imply () and ().

Proof

Since (O2) is satisfied we can apply Lemma 1 and conclude that neither nor Let with By Condition (O1) x has (at least two) children. Moreover, (O3) implies that there are (at least) two children v and w in T that are contained in distinct species V and W that are incomparable in S. Note, the edges (x, v) and (x, w) remain in , since only transfer edges are removed. Since no transfer is contained in , the genetic material v and w of V and W, respectively, is always vertically transmitted. Therefore, for any leaf we have and for any leaf we have in S. Assume now for contradiction, that . Let and with . Since and S is a tree, the species V and W must be comparable in S; a contradiction to (O3). Hence, Condition () is satisfied.

To see (), note that since (O2) is satisfied we can apply Lemma 1 and conclude that neither nor . Let . By (O3) the species containing V and W are incomparable in S. Now we can argue along the same lines as in the proof for () to conclude that .

From here on we simplify the notation a bit and write . We are aware of the fact that condition (O3) cannot be checked directly for a given event-labeled gene tree. In contrast, () and () are easily determined. Hence, in the remainder of this paper we consider the more general case, that is, gene trees that satisfy (O1), (O2), (), and ().

DTL-scenario and time-consistent reconciliation maps

In case that the event-labeling of T is unknown, but the gene tree T and a species tree S are given, the authors in [20, 24] provide an axiom set, called DTL-scenario, to reconcile T with S. This reconciliation is then used to infer the event-labeling t of T. Instead of defining a DTL-scenario as octuple [20, 24], we use here the notation established above:

Definition 1

(DTL-scenario) For a given gene tree on and a species tree S on the map maps the gene tree into the species tree such that

(I) For each leaf .

- (II) If with children v, w, then

- is not a proper descendant of or , and

- At least one of or is a descendant of

(III) (u, v) is a transfer edge if and only if and are incomparable.

- (IV) If with children v, w, then

- if and only if either (u, v) or (u, w) is a transfer-edge,

- If , then and are incomparable,

- If , then

DTL-scenarios are explicitly defined for fully resolved binary gene and species trees. Indeed, Fig. 1 (right) shows a valid reconciliation between a gene tree T and a species tree S that is not consistent with DTL-scenario. To see this, let us call the duplication vertex v. The vertex v and the leaf a are both children of the speciation vertex . Condition (IVb) implies that a and v must be incomparable. However, this is not possible since (Cond. (IVc)) and (Cond. (I)) and therefore, .

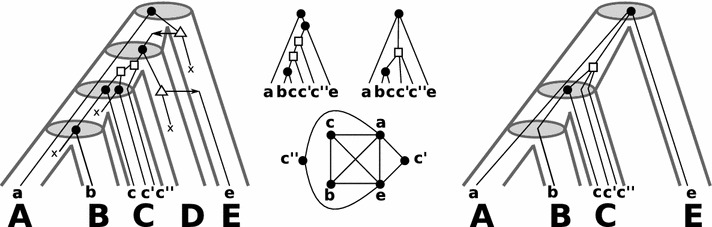

Fig. 1.

Left: A “true” evolutionary scenario for a gene tree with leaf set evolving along the tube-like species trees is shown. The symbol “x” denotes losses. All speciations along the path from the root to the leaf a are followed by losses and we omit drawing them. Middle: The observable gene tree is shown in the upper-left. The orthology graph (edges are placed between genes x, y for which ) is drawn in the lower part. This graph is a cograph and the corresponding non-binary gene tree T on that can be constructed from such data is given in the upper-right part (cf. [3, 4, 14] for further details). Right: Shown is species trees S on with reconciled gene tree T. The reconciliation map for T and S is given implicitly by drawing the gene tree T within S. Note, this reconciliation is not consistent with DTL-scenarios [20, 24]. A DTL-scenario would require that the duplication vertex and the leaf a are incomparable in S. Note, a non-binary duplication or HGT vertex v can always be “binary resolved” such that the newly created vertices are placed on the same edge as v. However, there are cases that show that non-binary speciation vertices cannot be “binary resolved”. For instance, for the non-binary gene tree T there is no way to resolve its root without violating the conditions of a reconciliation map (cf. [15, Fig. 3]). Yet, such cases strongly imply that the speciation event must have been followed by (several) duplication/HGT events that are not observable due to losses

The problem of reconciliations between gene trees and species tree is formalized in terms of so-called DTL-scenarios in the literature [20, 24]. This framework, however, usually assumes that the event labels t on T are unknown, while a species tree S is given. The “usual” DTL axioms, furthermore, explicitly refer to binary, fully resolved gene and species trees. We therefore use a different axiom set here that is a natural generalization of the framework introduced in [16] for the HGT-free case:

Definition 2

Let and be phylogenetic trees on and , resp., the assignment of genes to species and an event labeling on T. A map is a reconciliation map if for all it holds that:

(M1) Leaf Constraint. If , then .

- (M2) Event Constraint.

-

(i)If , then .

-

(ii)If , then .

-

(iii)If and , then and are incomparable in S.

-

(i)

(M3) Ancestor Constraint.

- Suppose with .

- (i) If , then ,

- (ii) Otherwise, i.e., at least one of t(v) and t(w) is a speciation , .

We say that S is a species tree for if a reconciliation map exists.

For the special case that gene and species trees are binary, Definition 2 is equivalent to the definition of a DTL-scenario, which is summarized in the following

Theorem 1

For a binary gene tree and a binary species tree S there is a DTL-scenario if and only if there is a reconciliation for and S.

The proof of Theorem 1 is a straightforward but tedious case-by-case analysis. In order to keep this section readable, we relegate the proof of Theorem 1 to "Proof of Theorem 1" section. Figure 1 shows an example of a biologically plausible reconciliation of non-binary trees that is valid w.r.t. Definition 2 but does not satisfy the conditions of a DTL-scenario.

Condition (M1) ensures that each leaf of T, i.e., an extant gene in , is mapped to the species in which it resides. Conditions (M2.i) and (M2.ii) ensure that each inner vertex of T is either mapped to a vertex or an edge in S such that a vertex of T is mapped to an interior vertex of S if and only if it is a speciation vertex. Condition (M2.i) might seem overly restrictive, an issue to which we will return below. Condition (M2.iii) satisfies condition (O3) and maps the vertices of a transfer edge in a way that they are incomparable in the species tree, since a HGT occurs between distinct (co-existing) species. It becomes void in the absence of HGT; thus Definition 2 reduces to the definition of reconciliation maps given in [16] for the HGT-free case. Importantly, condition (M3) refers only to the connected components of since comparability w.r.t. implies that the path between x and y in T does not contain transfer edges. It ensures that the ancestor order of T is preserved along all paths that do not contain transfer edges.

We will make use of the following bound that effectively restricts how close to the leafs the image of a vertex in the gene tree can be located.

Lemma 2

If satisfies (M1) and (M3), then for any

Proof

If u is a leaf, then by Condition (M1) and we are done. Thus, let u be an interior vertex. By Condition (M3), for all . Hence, if or if and are incomparable in S, then there is a such that z and are incomparable; contradicting (M3).

Condition (M2.i) implies in particular the weaker property “(M2.i’) if then ”. In the light of Lemma 2, is the lowest possible choice for the image of a speciation vertex. Clearly, this restricts the possibly exponentially many reconciliation maps for which for a speciation vertices v to only those that satisfy (M2.i). However, the latter is justified by the observation that if v is a speciation vertex with children u, w, then there is only one unique piece of information given by the gene tree to place , that is, the unique vertex x in S with children y, z such that and The latter arguments easily generalizes to the case that v has more than two children in T. Moreover, any observable speciation node closer to the root than v must be mapped to a node ancestral to due to (M3.ii). Therefore, we require here.

If S is a species tree for the gene tree then there is no freedom in the construction of a reconciliation map on the set . The duplication and HGT vertices of T, however, can be placed differently. As a consequence there is a possibly exponentially large set of reconciliation maps from to S.

From a biological point of view, however, the notion of reconciliation used so far is too weak. In the absence of HGT, subtrees evolve independently and hence, the linear order of points along each path from root to leaf is consistent with a global time axis. This is no longer true in the presence of HGT events, because HGT events imply additional time-consistency conditions. These stem from the fact that the appearance of the HGT copy in a distant subtree of S is concurrent with the HGT event. To investigate this issue in detail, we introduce time maps and the notion of time-consistency, see Figs. 2, 3, 4 for illustrative examples.

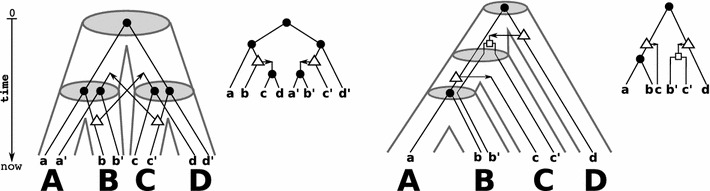

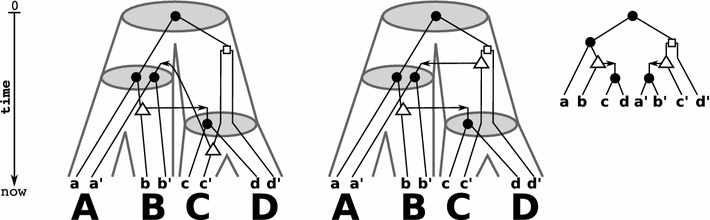

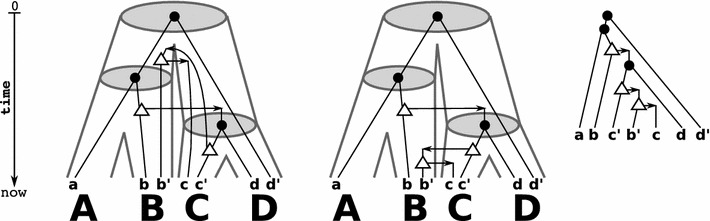

Fig. 2.

Shown are two (tube-like) species trees with reconciled gene trees. The reconciliation map for T and S is given implicitly by drawing the gene tree (upper right to the respective species tree) within the species tree. In the left example, the map is unique. However, is not time-consistent and thus, there is no time consistent reconciliation for T and S. In the example on the right hand side, is time-consistent

Fig. 3.

Shown are a gene tree (right) and two identical (tube-like) species trees S (left and middle). There are two possible reconciliation maps for T and S that are given implicitly by drawing T within the species tree S. These two reconciliation maps differ only in the choice of placing the HGT-event either on the edge or on the edge . In the first case, it is easy to see that would not be time-consistent, i.e., there are no time maps and that satisfy (C1) and (C2). The reconciliation map shown in the middle is time-consistent

Fig. 4.

Shown are a gene tree (right) and two identical (tube-like) species trees S (left and middle). There are two possible reconciliation maps for T and S that are given implicitly by drawing T within the species tree S. The left reconciliation maps each gene tree vertex as high as possible into the species tree. However, in this case only the middle reconciliation map is time-consistent

Definition 3

(Time Map) The map is a time map for the rooted tree T if implies for all .

Definition 4

A reconciliation map from to S is time-consistent if there are time maps for T and for S for all satisfying the following conditions:

(C1) If , then .

(C2) If and, thus , then .

Condition (C1) is used to identify the time-points of speciation vertices and leaves u in the gene tree with the time-points of their respective images in the species trees. In particular, all genes u that reside in the same species must be assigned the same time point . Analogously, all speciation vertices in T that are mapped to the same speciation in S are assigned matching time stamps, i.e., if and then .

To understand the intuition behind (C2) consider a duplication or HGT vertex u. By construction of it is mapped to an edge of S, i.e., in S. The time point of u must thus lie between time points of x and y. Now suppose is a transfer edge. By construction, u signifies the transfer event itself. The node v, however, refers to the next (visible) event in the gene tree. Thus . In particular, must not be misinterpreted as the time of introducing the HGT-duplicate into the new lineage. While this time of course exists (and in our model coincides with the timing of the transfer event) it is not marked by a visible event in the new lineage, and hence there is no corresponding node in the gene tree T.

W.l.o.g. we fix the time axis so that and . Thus, for all .

Clearly, a necessary condition to have biologically feasible gene trees is the existence of a reconciliation map . However, not all reconciliation maps are time-consistent, see Fig. 2.

Definition 5

An event-labeled gene tree is biologically feasible if there exists a time-consistent reconciliation map from to some species tree S.

As a main result of this contribution, we provide simple conditions that characterize (the existence of) time-consistent reconciliation maps and thus, provides a first step towards the characterization of biologically feasible gene trees.

Theorem 2

Let be a reconciliation map from to S. There is a time-consistent reconciliation map from to S if and only if there are two time-maps and for T and S, respectively, such that the following conditions are satisfied for all :

(D1) If , for some , then .

(D2) If for some with , then .

(D3) If for some , then .

Proof

In what follows, x and u denote vertices in S and T, respectively.

Assume that there is a time-consistent reconciliation map from to S, and thus two time-maps and for S and T, respectively, that satisfy (C1) and (C2).

To see (D1), observe that if , then (M1) and (M2) imply that . Now apply (C1).

To show (D2), assume that and . By Condition (M2) it holds that . Together with Lemma 2 we obtain that . By the properties of we have

To see (D3), assume that and . Since and by (M2ii), we have . Thus, . By (M2iii) and are incomparable and therefore, we have either or and y are incomparable. In either case we see that , since Lemma 2 implies that and . In summary, . Therefore,

Hence, conditions (D1)–(D3) are satisfied.

To prove the converse, assume that there exists a reconciliation map that satisfies (D1)–(D3) for some time-maps and . In the following we will make use of and to construct a time-consistent reconciliation map .

First we define “anchor points” by for all with . Condition (D1) implies for these vertices, and therefore satisfies (C1).

The next step will be to show that for each vertex with there is a unique edge (x, y) along the path from to with . We set for these points. In the final step we will show that is a valid reconciliation map.

Consider the unique path from to . By construction, and by Condition (D2) we have . Since is a time map for S, every edge satisfies . Therefore, there is a unique edge along such that either , , or . The addition of a sufficiently small perturbation to does not violate the conditions for being a time-map for T. Clearly can be chosen to break the equalities in the latter two cases in such a way that for each vertex with . We then continue with the perturbed version of and set . By construction, satisfies (C2).

It remains to show that is a valid reconciliation map from to S. Again, let denote the unique path from to for any .

By construction, Conditions (M1), (M2i), (M2ii) are satisfied. To check condition (M2iii), assume . The original map is a valid reconciliation map, and thus, Lemma 2 implies that and . Since and are incomparable in S and lies on both paths and we have . In particular, and .

Conditions (D1) and (D2) imply that and . By construction of , the vertex u is mapped to a unique edge and v is mapped either to or to the unique edge , respectively. In particular, lies on the path from x to and lies one the path from x to . The paths and are edge-disjoint and have x as their only common vertex. Hence, and are incomparable in S, and (M2iii) is satisfied.

In order to show (M3), assume that . Since , we have . Hence, . In other words, lies on the path and thus, is a subpath of . By construction of , both and are comparable in S. Moreover, since and by construction of , it immediately follows that .

Its now an easy task to verify that (M3) is fulfilled by considering the distinct event-labels in (M3i) and (M3ii), which we leave to the reader.

Interestingly, the existence of a time-consistent reconciliation map from a gene tree T to a species tree S can be characterized in terms of a time map defined on T, only.

Theorem 3

Let be a reconciliation map from to S. There is a time-consistent reconciliation map to S if and only if there is a time map such that for all

- (T1) If then

- (a) If , then .

- (b) If , then .

(T2) If , and , then .

(T3) If and for some , then

Proof

Suppose that is a time-consistent reconciliation map from to S. By Definition 4 and Theorem 2, there are two time maps and that satisfy (D1)–(D3). We first show that also satisfies (T1)–(T3), for all . Condition (T1a) is trivially implied by (D1). Let , and . Since and are time maps, we may conclude that

Hence, (T1b) is satisfied.

Now, assume that , and . By the properties of , we have:

Hence, (T2) is fulfilled.

Finally, assume that , and for some . Lemma 2 implies that and we obtain

Hence, (T3) is fulfilled.

To see the converse, assume that there exists a reconciliation map that satisfies (T1)–(T3) for some time map . In the following we construct a time map for S that satisfies (D1)–(D3). To this end, we first set

We use the symbol to denote the fact that so far no value has been assigned to . Note, by (M2i) and (T1a) the value is uniquely determined and thus, by construction, (D1) is satisfied. Moreover, if have non-empty preimages w.r.t. and , then we can use the fact that is a time map for T together with condition (T1) to conclude that .

If with , then (T2) implies (D2) [by (D1) and setting in (T2) and (T3) implies (D3) [by (D1) and setting in (T3)]. Thus, (D2) and (D3) is satisfied for all with .

Using our choices and for the augmented root of S, we must have . Thus, for any . Hence, (D2) is trivially satisfied for . Moreover, implies for any . Hence, (D3) is always satisfied for .

In summary, Conditions (D1)–(D3) are met for any vertex that up to this point has been assigned a value, i.e., .

We will now assign to all vertices with a value in a stepwise manner. To this end, we give upper and lower bounds for the possible values that can be assigned to . Let with . Set

We note that and because the root and the leaves of S already have been assigned a value in the initial step. In order to construct a valid time map we must ensure .

Moreover, we strengthen the bounds as follows. Put

Observe that , since otherwise there are vertices with and and . However, this implies that ; a contradiction to (T3).

Since (D2) is satisfied for all vertices y that obtained a value , we have . Likewise because of (D3), it holds that . Thus we set to an arbitrary value such that

By construction, (D1), (D2), and (D3) are satisfied for all vertices in V(S) that have already obtained a time value distinct from . Moreover, for all such vertices with we have . In each step we chose a vertex x with that obtains then a real-valued time stamp. Hence, in each step the number of vertices that have value is reduced by one. Therefore, repeating the latter procedure will eventually assign to all vertices a real-valued time stamp such that, in particular, satisfies (D1), (D2), and (D3) and thus is indeed a time map for S.

From the algorithmic point of view it is desirable to design methods that allow to check whether a reconciliation map is time-consistent. Moreover, given a gene tree T and species tree S we wish to decide whether there exists a time-consistent reconciliation map , and if so, we should be able to construct .

To this end, observe that any constraints given by Definition 3, Theorem 2 (D2)–(D3), and Definition 4 (C2) can be expressed as a total order on , while the constraints (C1) and (D1) together suggest that we can treat the preimage of any vertex in the species tree as a “single vertex”. In fact we can create an auxiliary graph in order to answer questions that are concerned with time-consistent reconciliation maps.

Definition 6

Let be a reconciliation map from to S. The auxiliary graph A is defined as a directed graph with a vertex set and an edge-set E(A) that is constructed as follows

- (A1) For each we have , where

and (A2) For each we have .

(A3) For each with we have .

(A4) For each we have

(A5) For each with and we have and .

We define and as the subgraphs of A that contain only the edges defined by (A1), (A2), (A5) and (A1), (A2), (A3), (A4), respectively.

We note that the edge sets defined by conditions (A1) through (A5) are not necessarily disjoint. The mapping of vertices in T to edges in S is considered only in condition (A5). The following two theorems are the key results of this contribution.

Theorem 4

Let be a reconciliation map from to S. The map is time-consistent if and only if the auxiliary graph is a directed acyclic graph (DAG).

Proof

Assume that is time-consistent. By Theorem 2, there are two time-maps and satisfying (C1) and (C2). Let be the map from . Let be the directed graph with and set for all : if and only if . By construction is a DAG since provides a topological order on [25].

We continue to show that contains all edges of .

To see that (A1) is satisfied for let . Note, , since is a time map for T and by construction of . Hence, all edges are also contained in , independent from the respective event-labels t(u), t(v). Moreover, if t(u) or t(v) are speciation vertices or leaves, then (C1) implies that or . By construction of , all edges satisfying (A1) are contained in . Since is a time map for S, all edges as in (A2) are contained in . Finally, (C2) implies that all edges satisfying (A5) are contained in .

Although, might have more edges than required by (A1), (A2) and (A5), the graph is a subgraph of . Since is a DAG, also is a DAG.

For the converse assume that is a directed graph with and edge set as constructed in Definition 6 (A1), (A2) and (A5). Moreover, assume that is a DAG. Hence, there is is a topological order on with whenever . In what follows we construct the time-maps and such that they satisfy (C1) and (C2). Set for all . Additionally, set for all :

By construction it follows that (C1) is satisfied. Due to (A2), is a valid time map for S. It follows from the construction and (A1) that is a valid time map for T. Assume now that , , and . Since provides a topological order we have:

By construction, it follows that satisfying (C2).

Theorem 5

Assume there is a reconciliation map from to S. There is a time-consistent reconciliation map, possibly different from , from to S if and only if the auxiliary graph (defined on ) is a DAG.

Proof

Let be a reconciliation map for and S and be a time-consistent reconciliation map for and S. Let and be the auxiliary graphs that satisfy Definition 6 (A1) – (A4) for and , respectively. Since for all with and (A2) – (A4) don’t rely on the explicit reconciliation map, it is easy to see that .

Now we can re-use similar arguments as in the proof of Theorem 4. Assume there is a time-consistent reconciliation map to S. By Theorem 2, there are two time-maps and satisfying (D1)-(D3). Let and be defined as in the proof of Theorem 4.

Analogously to the proof of Theorem 4, we show that contains all edges of . Application of (D1) immediately implies that all edges satisfying (A1) and (A2) are contained in . By condition (D2), it yields and (D3) implies . We conclude by the same arguments as before that the graph is a DAG.

For the converse, assume we are given the directed acyclic graph . As before, there is is a topological order on with only if . The time-maps and are given as in the proof of Theorem 1.

By construction, it follows that (D1) is satisfied. Again, by construction and the Properties (A1) and (A2), and are valid time-maps for S and T respectively.

Assume now that , , and for some . Since there is a topological order on , we have

By construction, it follows that . Thus, (D2) is satisfied.

Finally assume that and for some . Again, since provides a topological order, we have:

By construction, it follows that , satisfying (D3).

Thus and are valid time maps satisfying (D1)–(D3).

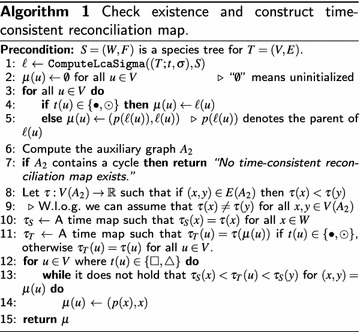

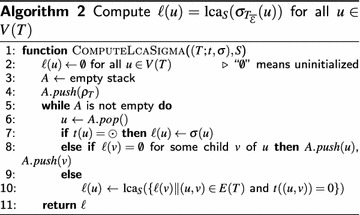

Naturally, Theorems 4 or 5 can be used to devise algorithms for deciding time-consistency. To this end, the efficient computation of for all is necessary. This can be achieved with Algorithm 2 in . More precisely, we have the following statement:

Lemma 3

For a given gene tree and a species tree Algorithm 2 correctly computes for all in time.

Proof

Let . In what follows, we show that . In fact, the algorithm is (almost) a depth first search through T that assigns the (species tree) vertex to u if and only if every child v of u has obtained an assignment (cf. Line (9)–(10)). That there are children v with non-empty at some point is ensured by Line (7). That is, if , then . Now, assume there is an interior vertex , where every child v has been assigned a value , then

The latter is achieved by Line (10).

Since T is a tree and the algorithm is in effect a depth first search through T, the while loop runs at most times, and thus in O(V(T)) time.

The only non-constant operation within the while loop is the computation of in Line (10). Clearly of a set of vertices , where , for all can be computed as sequence of operations taking two vertices: , each taking time. Note however, that since Line (10) is called exactly once for each vertex in T, the number of operations taking two vertices is called at most |E(T)| times through the entire algorithm. Hence, the total time complexity is .

Let S be a species tree for , that is, there is a valid reconciliation between the two trees. Algorithm 1 describes a method to construct a time-consistent reconciliation map for and S, if one exists, else “No time-consistent reconciliation map exists” is returned. First, an arbitrary reconciliation map that satisfies the condition of Definition 2 is computed. Second, Theorem 5 is utilized and it is checked whether the auxiliary graph is not a DAG in which case no time-consistent map exists for and S. Finally, if is a DAG, then we continue to adjust to become time-consistent. The latter is based on Theorem 2, see the proof of Theorems 2 and 6 for details.

Theorem 6

Let be species tree for the gene tree . Algorithm 1 correctly determines whether there is a time-consistent reconciliation map and in the positive case, returns such a in time.

Proof

In order to produce a time-consistent reconciliation map, we first construct some valid reconciliation map from to S. Using the -map from Algorithm 2, will be adjusted to become time-consistent, if possible.

By assumption, there is a reconciliation map from to S. The for-loop (Line (3)–(5)) ensures that each vertex obtained a value . We continue to show that is a valid reconciliation map satisfying (M1)–(M3).

Assume that , in this case , and thus (M1) is satisfied. If , it holds that , thus satisfying (M2i). Note that , and hence, by Line (5), implying that (M2ii) is satisfied. Now, assume and . By assumption, we know there exists a reconciliation map from T to S, thus by ():

It follows that, is incomparable to , satisfying (M2iii).

Now assume that and . Note that . It follows that . By construction, (M3) is satisfied. Thus, is a valid reconciliation map.

By Theorem 5, two time maps and satisfying (D1)–(D3) only exists if the auxiliary graph A build on Line (7) is a DAG. Thus if contains a cycle, no such time-maps exists and the statement “No time-consistent reconciliation map exists.” is returned (Line (7)). On the other hand, if A is a DAG, the construction in Line (8)–(11) is identical to the construction used in the proof of Theorem 5. Hence correctness of this part of the algorithm follows directly from the proof of Theorem 5.

Finally, we adjust to become a time-consistent reconciliation map.. By the latter arguments, and satisfy (D1)–(D3) w.r.t. to . Note, that is chosen to be the “lowest point” where a vertex with can be mapped, that is, is set to (p(x), x) where . However, by the arguments in the proof of Theorem 2, there is a unique edge on the path from x to such that . The latter is ensured by choosing a different value for distinct vertices in V(A), see comment in Line (9). Hence, Line (14) ensures, that is mapped on the correct edge such that (C2) is satisfied. It follows that adjusted is a valid time-consistent reconciliation map.

We are now concerned with the time-complexity. By Lemma 3, computation of in Line (1) takes time and the for-loop (Line (3)-(5)) takes O(|V|) time. We continue to show that the auxiliary graph A (Line (6)) can be constructed in time.

Since we know for all and since T and S are trees, the subgraph with edges satisfying (A1)–(A3) can be constructed in time. To ensure (A4), we must compute for a possible transfer edges the vertex . which can be done in time. Note, the number of transfer edges is bounded by the number of possible transfer event O(|V|). Hence, generating all edges satisfying (A4) takes time. In summary, computing A can done in time.

To detect whether A contains cycles one has to determine whether there is a topological order on V(A) which can be done via depth first search in time. Since and and S, T are trees, the latter task can be done in time. Clearly, Line (10)-(11) can be performed on time.

Finally, we have to adjust according to and . Note, that for each with (Line (12)) we have possibly adjust to the next edge (p(x), x). However, the possibilities for the choice of (p(x), x) is bounded by by the height of S, which is in the worst case . Hence, the for-loop in Line (12) has total-time complexity .

In summary, the overall time complexity of Algorithm 1 is .

So far, we have shown how to find a time consistent reconciliation map given a species tree S and a single gene tree T. In practical applications, however, one often considers more than one gene family, and thus, a set of gene trees that has to be reconciled with one and the same species tree S.

In this case it is possible to aggregate all gene trees to a single gene tree that is constructed from F by introducing an artificial duplication as the new root of all . More precisely, is constructed from F such that and . Moreover, the event-labeling map t is defined as

Finally, for all .

Finding a time consistent reconciliation for a species tree S and a set of gene trees F then corresponds to finding a time map for S and a time map for the aggregated gene tree , such that (D1)–(D3) are satisfied.

If there exists a time consistent reconciliation map from to S then, by Theorem 2, there exists the two time maps and that satisfy (D1)–(D3). But then and also satisfy (D1)–(D3) w.r.t. any and therefore, immediately gives a time-consistent reconciliation map for each .

Outlook and summary

We have characterized here whether a given event-labeled gene tree and species tree S can be reconciled in a time-consistent manner in terms of two auxiliary graphs and that must be DAGs. These are defined in terms of given reconciliation maps. This condition yields an -time algorithm to check whether a given reconciliation map is time-consistent, and an algorithm with the same time complexity for the construction of a time-consistent reconciliation maps, provided one exists.

Our results depend on three conditions on the event-labeled gene trees that are motivated by the fact that event-labels can be assigned to internal vertices of gene trees only if there is observable information on the event. The question which event-labeled gene trees are actually observable given an arbitrary, true evolutionary scenario deserves further investigation in future work. Here we have used conditions that arguable are satisfied when gene trees are inferred using sequence comparison and synteny information. A more formal theory of observability is still missing, however.

Our results point to an efficient way of deciding whether a given pair of gene and species tree can be time-consistently reconciled. Such gene and species trees can be obtained from genomic sequence data using the following workflow: (i) Estimate putative orthologs and HGT events using e.g. one of the methods detailed in [11, 12, 26–38], respectively. Importantly, this step uses only sequence data as input and does not require the construction of either gene or species trees. (ii) Correct these estimates in order to derive “biologically feasible” homology relations as described in [15, 16, 26, 39–44]. The result of this step are (not necessarily fully resolved) gene trees together with event-labels. (iii) Extract “informative triples” from the event-labeled gene tree. These imply necessary conditions for gene trees to be biologically feasible [15, 16].

In general, there will be exponentially many putative species trees. This begs the question whether there is at least one species tree S for a gene tree and if so, how to construct S. In the absence of HGT, the answer is known: time-consistent reconciliation maps are fully characterized in terms of “informative triples” [16]. Hence, the central open problem that needs to be addressed in further research are sufficient conditions for the existence of a time-consistent species tree given an event-labeled gene tree with HGT.

Proof of Theorem 1

We show that Definition 2 is is equivalent to the traditional definition of a DTL-scenario [20, 24] in the special case that both the gene tree and species trees are binary. To this end we establish a series of lemmas detailing some useful properties of reconciliation maps.

Lemma 4

Let be a reconciliation map from to S and assume that T is binary. Then the following conditions are satisfied:

If are in the same connected component of then Let u be an arbitrary interior vertex of T with children v, w, then:

and are incomparable in S if and only if

If then and are incomparable in S.

If are comparable or then

Proof

We prove the Items 1 – 4 separately. Recall, Lemma 1 implies that for all .

Proof of Item 1: Let v and w be distinct vertices of T that are in the same connected component of . Consider the unique path P connecting w with v in . This path P is uniquely subdivided into a path and a path from to v and w, respectively. Condition (M3) implies that the images of the vertices of and under , resp., are ordered in S with regards to and hence, are contained in the intervals and that connect with and , respectively. In particular, is the largest element (w.r.t. ) in the union of which contains the unique path from to and hence also .

Proof of Item 2: If then, and (M2iii) implies that and are incomparable.

To see the converse, let and be incomparable in S. Item (M3) implies that for any edge we have . However, since and are incomparable it must hold that . Since (u, v) is an edge in the gene tree T, is a transfer edge.

Proof of Item 3: Let . Since none of (u, v) and (u, w) are transfer-edges, it follows that both edges are contained in .

Then, since T is a binary tree, it follows that and therefore,

Therefore and by Item (M2i),

Assume for contradiction that and are comparable, say, . By Lemma 2, and . Thus,

Thus, ; a contradiction to (M3ii).

Proof of Item 4: Let be comparable in S. Item 3 implies that . Assume for contradiction that . Since by (O2) only one of the edges (u, v) and (u, w) is a transfer edge, we have either or . W.l.o.g. let and . By Condition (M3), . However, since and are comparable in S, also and are comparable in S; a contradiction to Item 2. Thus, . Since each interior vertex is labeled with one event, we have .

Assume now that . Hence, is comparable to both and and thus, (M2iii) implies that . Lemma 2 implies and . Hence,

Since it follows that neither nor and hence, both edges are contained in . By the same argumentation as in Item 3 it follows that and therefore, . Hence, . Now, (M2i) implies . Since each interior vertex is labeled with one event, we have .

Lemma 5

Let be a reconciliation map for the gene tree and the species tree S as in Definition 2. Moreover, assume that T and S are binary. Set for all

Then is a map according to the DTL-scenario.

Proof

We first emphasize that, by construction, for all . Moreover, implies that , and implies that and are comparable. Furthermore, implies , while implies that . Thus, and are comparable if and only if and are comparable.

Item (I) and (M1) are equivalent.

For Item (II) let be an interior vertex with children v, w. If , then . Applying Condition (M3) yields and thus, by construction, . Therefore, is not a proper descendant of and is a descendant of . If one of the edges, say (u, v), is a transfer edge, then and by Condition (M2iii) and are incomparable. Hence, and are incomparable. Therefore, is no proper descendant of . Note that (O2) implies that for each vertex at least one of its outgoing edges must be a non-transfer edge, which implies that or as shown before. Hence, Item (IIa) and (IIb) are satisfied.

For Item (III) assume first that and therefore . Then, (M2iii) implies that and are incomparable and thus, and are incomparable. Now assume that (u, v) is an edge in the gene tree T and and are incomparable. Therefore, and are incomparable. Now, apply Lemma 4(2).

Item (IVa) is clear by the event-labeling t of T and since (O2). Now assume for (IVb) that . Lemma 4(3) implies that and are incomparable and thus, and must be incomparable as well. Furthermore, Condition (M2i) implies that . Lemma 2 implies that and . The latter together with the incomparability of and implies that

If is mapped on the edge (x, y) in T, then . By definition of for edges, . The same argument applies if is mapped on an edge. Since for all either (if is mapped on an edge) or , we always have

Since , (M2i) implies that and therefore, by construction of it holds that . Thus, . For (IVc) assume that . Condition (M3) implies that and therefore, . If and are incomparable, then implies that . If and are comparable, say , then . Hence, Statement (IVc) is satisfied.

Lemma 6

Let be a map according to the DTL-scenario for the binary the gene tree and the binary species tree S. For all define:

Then is a reconciliation map according to Definition 2.

Proof

Let be a map a DTL-scenario for the binary the gene tree and the species tree S.

Condition (M1) is equivalent to (I).

For (M3) assume that . The path P from v to w in does not contain transfer edges. Thus, by (III) all vertices along P are comparable. Moreover, by (IIa) we have that is not a proper descendant of the image of its child in S, and therefore, by repeating these arguments along the vertices x in , we obtain .

If , then by construction of , it follows that . Thus, (M3) is satisfied, whenever . Assume now that . If then and thus (M3i) is satisfied. If and then since and . Thus .

Now assume that and w is a speciation vertex. Since , for its two children and the images and must be incomparable due to (IVb). W.l.o.g. assume that is a vertex of . Since for any vertex x along and , we obtain . However, since , the vertices and are comparable in S; contradicting (IVb). Thus, whenever w is a speciation vertex, is not possible. Therefore, and, by construction of , . Thus, (M3ii) is satisfied.

Finally, we show that (M2) is satisfied. To this end, observe first that (M2ii) is fulfilled by construction of and (M2iii) is an immediate consequence of (III). Thus, it remains to show that (M2i) is satisfied. Thus, for a given speciation vertex u we need to show that . By construction, . Note, does not contain transfer edges. Applying (III) implies that for all edges (x, y) in the images and must be comparable. The latter and (IIa) implies that for all edges (x, y) in we have . Take the latter together, for any leaf . Therefore . Assume for contradiction that . Consider the two children and of u in . Since neither nor and T is a binary tree, it follows that and we obtain that . Moreover, re-using the arguments above, and . By the arguments we used in the proof for (M3), we have and . In particular, and must be contained in the subtree of S that is rooted in the child a of in S with , as otherwise, or . Moreover, neither nor is possible since then and implies that and would be comparable; contradicting (IVb). Hence, there remains only one way to locate and , that is, they must be located in the subtree of S that is rooted in . But then we have ; a contradiction to (IVb) . Therefore, and (M2i) is satisfied.

Authors' contributions

NN and MH designed the study. NN implemented and designed the algorithms. All authors collaborated in research and the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the organizers of the 32nd TBI Winterseminar 2017 in Bled (Slovenia), where the authors met and jointly drafted the main ideas of this paper with the help of an unknown number of cold and tasty cans of red Union, or was it green Laško?

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

Supported in part by the Danish Council for Independent Research, Natural Sciences, Grants DFF-1323-00247 and DFF-7014-00041.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nikolai Nøjgaard, Email: nojgaard@imada.sdu.dk.

Manuela Geiß, Email: manuela@bioinf.uni-leipzig.de.

Daniel Merkle, Email: daniel@imada.sdu.dk.

Peter F. Stadler, Email: studla@bioinf.uni-leipzig.de

Nicolas Wieseke, Email: wieseke@informatik.uni-leipzig.de.

Marc Hellmuth, Email: mhellmuth@mailbox.org.

References

- 1.Dress A, Moulton V, Steel M, Wu T. Species, clusters and the ‘tree of life’: a graph-theoretic perspective. J Theor Biol. 2010;265:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitch WM. Homology: a personal view on some of the problems. Trends Genet. 2000;16:227–231. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellmuth M, Stadler PF, Wieseke N. The mathematics of xenology: di-cographs, symbolic ultrametrics, 2-structures and tree- representable systems of binary relations. J Math Biol. 2016;75(1):199–237. doi: 10.1007/s00285-016-1084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hellmuth M, Wieseke N. From sequence data including orthologs, paralogs, and xenologs to gene and species trees. In: Pontarotti P, editor. Evolutionary Biology: convergent evolution, evolution of complex traits, concepts and methods. Cham: Springer; 2016. pp. 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guigó R, Muchnik I, Smith T. Reconstruction of ancient molecular phylogeny. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996;6:189–213. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page RDM, Charleston MA. Trees within trees: phylogeny and historical associations. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13:356–359. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01438-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zmasek C, Eddy S. A simple algorithm to infer gene duplication and speciation events on a gene tree. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:821–828. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernot B, Stolzer M, Goldman A, Durand D. Reconciliation with non-binary species trees. J Comput Biol. 2008;15:981–1006. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2008.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellmuth M, Wieseke N, Lechner M, Lenhof H-P, Middendorf M, Stadler PF. Phylogenomics with paralogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(7):2058–2063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412770112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth ACJ, Gonnet GH, Dessimoz C. Algorithm of OMA for large-scale orthology inference. BMC Bioinf. 2008;9:518. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altenhoff AM, Dessimoz C. Phylogenetic and functional assessment of orthologs inference projects and methods. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:1000262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lechner M, Hernandez-Rosales M, Doerr D, Wieseke N, Thévenin A, Stoye J, Hartmann RK, Prohaska SJ, Stadler PF. Orthology detection combining clustering and synteny for very large datasets. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):105015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altenhoff AM, Boeckmann B, Capella-Gutierrez S, Dalquen DA, DeLuca T, Forslund K, Huerta-Cepas J, Linard B, Pereira C, Pryszcz LP, Schreiber F, da Silva AS, Szklarczyk D, Train CM, Bork P, Lecompte O, von Mering C, Xenarios I, Sjölander K, Jensen LJ, Martin MJ, Muffato M, Gabaldón T, Lewis SE, Thomas PD, Sonnhammer E, Dessimoz C. Standardized benchmarking in the quest for orthologs. Nat Methods. 2016;13:425–430. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellmuth M, Hernandez-Rosales M, Huber KT, Moulton V, Stadler PF, Wieseke N. Orthology relations, symbolic ultrametrics, and cographs. J Math Biol. 2013;66(1–2):399–420. doi: 10.1007/s00285-012-0525-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellmuth M. Biologically feasible gene trees, reconciliation maps and informative triples. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2017;12(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13015-017-0114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez-Rosales M, Hellmuth M, Wieseke N, Huber KT, Moulton V, Stadler PF. From event-labeled gene trees to species trees. BMC Bioinf. 2012;13(Suppl 19):6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyon J-P, Ranwez V, Daubin V, Berry V. Models, algorithms and programs for phylogeny reconciliation. Brief Bioinf. 2011;12(5):392. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbr045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merkle D, Middendorf M. Reconstruction of the cophylogenetic history of related phylogenetic trees with divergence timing information. Theor Biosci. 2005;4:277–299. doi: 10.1016/j.thbio.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charleston MA. Jungles: a new solution to the host/parasite phylogeny reconciliation problem. Math Biosci. 1998;149(2):191–223. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(97)10012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tofigh A, Hallett M, Lagergren J. Simultaneous identification of duplications and lateral gene transfers. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinf. 2011;8(2):517–535. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2010.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Böcker S, Dress AWM. Recovering symbolically dated, rooted trees from symbolic ultrametrics. Adv Math. 1998;138:105–125. doi: 10.1006/aima.1998.1743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellmuth M, Wieseke N. On symbolic ultrametrics, cotree representations, and cograph edge decompositions and partitions. Cham: Springer; 2015. pp. 609–623. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hellmuth M, Wieseke N. On tree representations of relations and graphs: Symbolic ultrametrics and cograph edge decompositions. J Comb Optim. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bansal MS, Alm EJ, Kellis M. Efficient algorithms for the reconciliation problem with gene duplication, horizontal transfer and loss. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):283–291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahn AB. Topological sorting of large networks. Commun ACM. 1962;5(11):558–562. doi: 10.1145/368996.369025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altenhoff AM, Gil M, Gonnet GH, Dessimoz C. Inferring hierarchical orthologous groups from orthologous gene pairs. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):53786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altenhoff AM, et al. The OMA orthology database in 2015: function predictions, better plant support, synteny view and other improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(D1):240–249. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen F, Mackey AJ, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS. OrthoMCL-db: querying a comprehensive multi-species collection of ortholog groups. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(S1):363–368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lechner M, Findeiß S, Steiner L, Marz M, Stadler PF, Prohaska SJ. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Östlund G, Schmitt T, Forslund K, Köstler T, Messina DN, Roopra S, Frings O, Sonnhammer ELL. InParanoid 7: new algorithms and tools for eukaryotic orthology analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(suppl 1):196–203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trachana K, Larsson TA, Powell S, Chen W-H, Doerks T, Muller J, Bork P. Orthology prediction methods: a quality assessment using curated protein families. BioEssays. 2011;33(10):769–780. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wheeler DL, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, Dicuccio M, Edgar R, Federhen S, Feolo M, Geer LY, Helmberg W, Kapustin Y, Khovayko O, Landsman D, Lipman DJ, Madden TL, Maglott DR, Miller V, Ostell J, Pruitt KD, Schuler GD, Shumway M, Sequeira E, Sherry ST, Sirotkin K, Souvorov A, Starchenko G, Tatusov RL, Tatusova TA, Wagner L, Yaschenko E. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:13–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clarke GDP, Beiko RG, Ragan MA, Charlebois RL. Inferring genome trees by using a filter to eliminate phylogenetically discordant sequences and a distance matrix based on mean normalized BLASTP scores. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(8):2072–2080. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.8.2072-2080.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dessimoz C, Margadant D, Gonnet GH. DLIGHT—lateral gene transfer detection using pairwise evolutionary distances in a statistical framework. In: Proceedings RECOMB 2008, pp. 315–330. Springer, Berlin; 2008.

- 36.Lawrence JG, Hartl DL. Inference of horizontal genetic transfer from molecular data: an approach using the bootstrap. Genetics. 1992;131(3):753–760. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.3.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pellegrini M, Marcotte EM, Thompson MJ, Eisenberg D, Yeates TO. Assigning protein functions by comparative genome analysis: protein phylogenetic profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(8):4285–4288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravenhall M, Škunca N, Lassalle F, Dessimoz C. Inferring horizontal gene transfer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11(5):1004095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dondi R, Lafond M, El-Mabrouk N. Approximating the correction of weighted and unweighted orthology and paralogy relations. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2017;12(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13015-017-0096-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lafond M, El-Mabrouk N. Orthology and paralogy constraints: satisfiability and consistency. BMC Genom. 2014;15(6):12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-S6-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lafond M, El-Mabrouk N. Orthology relation and gene tree correction: complexity results. In: International workshop on algorithms in bioinformatics, Berlin: Springer; 2015. p. 66–79.

- 42.Dondi R, El-Mabrouk N, Lafond M. Correction of weighted orthology and paralogy relations-complexity and algorithmic results. In: International workshop on algorithms in bioinformatics, Berlin: Springer; 2016. p. 121–36.

- 43.Dondi R, Mauri G, Zoppis I. Orthology correction for gene tree reconstruction: Theoretical and experimental results. Procedia Computer Science. International Conference on Computational Science, ICCS 2017, 12-14 June 2017, Zurich, Switzerland. p. 1115–24.

- 44.Lafond M, Dondi R, El-Mabrouk N. The link between orthology relations and gene trees: a correction perspective. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2016;11(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13015-016-0067-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.