Abstract

Background

Decidual senescence has been considered a mechanism of disease for spontaneous preterm labor in the absence of severe acute inflammation. Yet, signs of cellular senescence have also been observed in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent the physiological process of labor at term.

Objective

We aimed to investigate whether, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor or labor at term exhibit markers of cellular senescence.

Study Design

Chorioamniotic membrane samples were collected from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor or labor at term. Gestational age-matched non-labor controls were also included. Senescence-associated genes/proteins were determined using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis (n=7–9 each for array; n= 26–28 each for validation), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (n=7–9 each), immunoblotting (n=6–7 each) and immunohistochemistry (n=7–8 each). Senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity (n=7–11 each) and telomere length (n=15–22 each) were also evaluated.

Results

In the chorioamniotic membranes without acute histologic chorioamnionitis: 1) the expression profile of senescence-associated genes was different between the labor groups (term in labor and preterm in labor) and the non-labor groups (term no labor and preterm no labor); yet, there were differences between the term in labor and preterm in labor groups; 2) most of the differentially expressed genes among the groups were closely related to the tumor suppressor protein 53 (TP53) pathway; 3) the expression of TP53 was down-regulated in the term in labor and preterm in labor groups compared to their non-labor counterparts; 4) the expression of CDKN1A (gene coding for p21) was up-regulated in the term in labor and preterm in labor groups compared to their non-labor counterparts; 5) the expression of the cyclin kinase CDK2 and cyclins CCNA2, CCNB1 and CCNE1 was down-regulated in the preterm in labor group compared to the preterm no labor group; 6) the concentration of TP53 was lower in the preterm in labor group than in the preterm no labor and term in labor groups; 7) the senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity was greater in the preterm in labor group than in the preterm no labor and term in labor groups; 8) the concentration of phospho-S6 ribosomal protein was reduced in the term in labor group compared to its non-labor counterpart but no differences were observed between the preterm in labor and preterm no labor groups, and 9) no significant differences were observed in relative telomere length among the study groups (term no labor, term in labor, preterm no labor, and preterm in labor).

Conclusion

In the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, signs of cellular senescence are present in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor compared to those who delivered preterm in the absence of labor. However, the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous labor at term did not show consistent signs of cellular senescence in the absence of histologic chorioamnionitis. These results suggest that different pathways are implicated in the pathological and physiological processes of labor.

Keywords: acute histologic chorioamnionitis, cell cycle, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (p21), cyclin kinases, cyclins, decidua parietalis, human, intra-amniotic infection, parturition, pregnancy, preterm birth, preterm labor, senescence-associated β-galactosidase, sterile inflammation, telomere length, tumor suppressor protein 53 (TP53)

INTRODUCTION

Cellular senescence is a process in which cells stop dividing and undergo alterations in their phenotype, chromatin, secretome, and tumor suppressor activation1. Such a process is described as an irreversible cell cycle arrest, which is a result of the overexpression of the cyclin kinase inhibitors, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (p21CDK1), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16INKT/6/CDKN2) as well as alterations in the tumor suppressor protein 53 (TP53) pathway1, 2. Senescent cells are generally non-proliferative and can be identified by their enlarged nuclei with aberrant distribution of heterochromatin and prominent nucleoli, flattened morphology with marked actin stress fibers, and chronic DNA damage2–5.

In the placenta, cellular senescence was first described using morphological and histological characteristics6–11, where it is considered a physiological process of aging in this organ10, 12. Decidual senescence, however, is proposed to be a mechanism of disease for spontaneous preterm labor13, 14, a syndrome of multiple pathological processes14 that frequently leads to preterm birth15–19, the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide20–23. Such a hypothesis is supported by the fact that, in pregnant mice with a uterine-specific deletion of transformation-related protein 53 (Trp53), the rate of preterm birth and decidual senescence [evidenced by senescence-associated beta galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity24] was greater than in the control mice13. In addition, mice with a uterine-specific deletion of Trp53 display an increased expression of p2113, pAkt13 (also known as protein kinase B or PKB) and phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (pS6)25, as well as a reduced expression of antioxidant enzymes, in the decidua26. The mechanisms whereby decidual senescence results in spontaneous preterm labor seem to be independent of severe acute inflammation since wild-type mice do not exhibit characteristics of cellular senescence upon injection with lipopolysaccharide (LPS)25, which induces preterm birth27–30. In humans, however, whether decidual senescence is a mechanism of disease for spontaneous preterm labor in the absence of severe acute inflammation is still under investigation.

Yet, cellular senescence is also considered a physiological mechanism for parturition at term31, 32. Such a concept is supported by evidence demonstrating that the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous labor at term display morphological characteristics of cellular senescence (enlarged cells and organelles) and have increased SA-β-gal activity compared to those from women who delivered at term without labor33. In addition, women who underwent spontaneous labor at term have an elevated amniotic fluid concentration of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) markers [granulocytes macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8]33, a greater number of telomere fragments in the amniotic fluid 34, and a shorter telomere length and reduced lamin B1 in the chorioamnionitic membranes, as well as an upregulation of p2135, compared to those who delivered at term without labor. Further, in the murine chorioallantoic membranes, the telomere length shortens as the presence of mitogen-activated kinase p38 (p38-MAPK)36, active TP53, and SA-β-gal activity increases gradually throughout gestation37.

The aim of the current study was to investigate whether, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis (severe acute inflammation), the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor and those who had undergone spontaneous labor at term exhibit markers of cellular senescence compared to gestational-age-matched non-labor controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Subjects

Chorioamniotic membrane samples were collected from women who delivered at term with or without spontaneous labor. Chorioamniotic membrane samples were also collected from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor or delivered preterm in the absence of labor due to clinical indications. Sampling of the chorioamniotic membranes included the peri-placental, middle and rupture zones38–41 (spontaneous rupture zone in cases with labor and mechanical rupture zone in cases without labor). These samples were obtained from the Bank of Biological Specimens of the Detroit Medical Center, Wayne State University, and the Perinatology Research Branch, an intramural program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS) (Detroit, MI, USA). The Institutional Review Boards of Wayne State University and NICHD approved the collection and use of biological materials for research purposes. All participating women provided written consent and samples were collected within 30 minutes after delivery. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are displayed in Tables 1–3. All of the women in the study had singleton pregnancies and patients with neonates who had congenital or chromosomal abnormalities were excluded. Most of the chorioamniotic membranes samples were obtained from women without preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes [pPROM (>97%)]. Labor at term was defined as the presence of regular uterine contractions at a minimum frequency of two contractions every 10 minutes associated with cervical changes resulting in delivery ≥37 weeks of gestation42. Preterm labor was diagnosed by the presence of regular uterine contractions (at least 3 in 30 minutes) and documented cervical changes in patients with a gestational age between 20 and 36 6/7 weeks. Preterm delivery was defined as birth prior to the 37th week of gestation. In each case, tissue sections of the chorioamniotic membranes were evaluated for acute histologic chorioamnionitis, according to published criteria43, 44, by pathologists who were blind to the clinical outcome. Samples collected from women with acute histologic chorioamnionitis were excluded from this study. The preterm no labor group included chorioamniotic membrane samples from women who delivered preterm due to clinical indications such as preeclampsia. The term no labor group included chorioamniotic membrane samples from women with a prior history of cesarean section, malpresentation, and/or cesarean delivery on maternal request.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of women whose samples were used in the RT-qPCR gene expression array, ELISA assays, immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry, and senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining

| Term no labor (n=9) | Term in labor (n=8) | Preterm no labor (n=11) | Preterm in labor (n=9) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age years; median (IQR)a | 29 (23–30) | 24 (21.5–28.7) | 31 (25.5–35.5) | 25 (22–30) | NS |

|

| |||||

| Body mass index kg/m2; median (IQR)a | 35.7 (30.2–39.4) | 29.1 (26.9–39.1) | 24.7 (22.6–31.3) | 24.2 (23.8–25.4) | 0.009 |

|

| |||||

| Gestational age at delivery weeks; median (IQR)a | 39.4 (38.9–40) | 39.8 (38.5–40.95) | 30.3 (29.8–31.65) | 31.7 (30.9–33) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Birth weight g; median (IQR)a | 3560 (3385–3680) | 3350 (3186–3548) | 1100 (876–1307) | 1605 (1530–2110) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Race n (%)b | NS | ||||

| African-American | 8 (88.9%) | 7 (87.5%) | 7 (63.6%) | 6 (66.7%) | |

| Caucasian | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18.2%) | 3 (33.3%) | |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

|

| |||||

| Primiparity n (%)b | 0 (0%) | 2 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | NS |

|

| |||||

| C-section n (%)b | 9 (100%) | 2 (25%) | 11 (100%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Acute Chorioamnionitis n (%)b | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

IQR, interquartile range; NS, non-significant; NA, not applicable

Kruskal–Wallis test

x2 test

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the women whose samples were used for telomere length determination

| Term no labor (n=20) | Term in labor (n=16) | Preterm no labor (n=22) | Preterm in labor (n=15) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age years; median (IQR)a | 27 (24–30) | 23.5 (22–29.2) | 31 (27.2–33.8) | 23 (21–28) | NS |

|

| |||||

| Body mass index kg/m2; median (IQR)a | 34.5 (29.8–39.5) | 26.2 (22.1–31.5) | 29.2 (24.4–37.6) | 23.1 (22–30.7) | NS |

|

| |||||

| Gestational age at delivery weeks; median (IQR)a | 38.9 (37.9–39.4) | 38.9 (38.5–39.9) | 33.8 (30.6–35.6) | 34 (29.9–34.6) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Birth weight g; median (IQR)a | 3532 (2910–3895) | 3142.5 (2624–3255) | 2020 (1216–2596) | 1970 (1158–2380) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Race n (%)b | NS | ||||

| African-American | 15 (75%) | 16 (100%) | 16 (72.7%) | 13 (86.7%) | |

| Caucasian | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (18.2%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Other | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

|

| |||||

| Primiparity n(%)b | 0 (0%) | 4 (25%) | 6 (27.3%) | 3 (20%) | NS |

|

| |||||

| C-section n(%)b | 20 (100%) | 3 (18.8%) | 22 (100%) | 2 (13.3%) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Acute Chorioamnionitis n(%)b | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

IQR, interquartile range; NS, non-significant; NA, not applicable

Kruskal–Wallis test

x2 test

RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and Reverse Transcription quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the chorioamniotic membranes using TRIzol® reagent (Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island, NY, USA) and the RNeasy® Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturers’ instructions. RNA purity and concentrations were assessed with the NanoDrop™ 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc., Walatham, MA, USA) and RNA integrity was evaluated with the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The expression profile of 84 senescence-associated genes was initially determined in a small set of samples (n=7–9 per group, Table 1) using the RT2 Profiler PCR Array (Qiagen) on the ABI 7500 FAST Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems®, Life Technologies Corporation, Foster City, CA, USA). The expression levels of selected genes (Supplementary Table) were validated in a larger set of samples (n=26–28 samples per group, Table 2) using the BioMark™ System for high-throughput RT-qPCR (Fluidigm®, San Francisco, CA, USA).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the women whose samples were used for RT-qPCR validation

| Term no labor (n=28) | Term in labor (n=28) | Preterm no labor (n=27) | Preterm in labor (n=26) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age years; median (IQR)a | 26.5 (22.8–29.3) | 22.5 (20–25) | 24 (21–27) | 23 (20–25) | 0.047 |

|

| |||||

| Body mass index kg/m2; median (IQR)a | 28.3 (25.3–35.4) | 22.7 (19.8–25.9) | 27.3 (23.9–34.1) | 22.1 (20–25.2) | 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Gestational age at delivery weeks; median (IQR)a | 39.3 (39–39.7) | 39.7 (39.2–40.2) | 32.9 (29.8–34.2) | 33.8 (31.3–35.3) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Birth weight g; median (IQR)a | 3293 (3104–3633) | 3238 (3076–3490) | 1480 (908–1865) | 1980 (1558–2155) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Race (n)b | NS | ||||

| African-American | 22 (78.5%) | 22 (78.5%) | 26 (96.2%) | 24 (92.3%) | |

| Caucasian | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (3.6 %) | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (3.8%) | |

|

| |||||

| Primiparity n (%)b | 1 (3.6%) | 5 (17.8%) | 4 (14.8%) | 2 (8%) | NS |

|

| |||||

| C-section n (%)b | 28 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 27 (100%) | 8 (31%) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Acute Chorioamnionitis n (%)b | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

IQR, interquartile range; NS, non-significant; NA, not applicable

Kruskal–Wallis test

x2 test

Chorioamniotic Membrane Tissue Lysates

Fragments of snap-frozen chorioamniotic membranes (n=8–11 per group, Table 1) were homogenized using a mechanical tissue homogenizer (PRO 200® from Pro Scientific Inc., Oxford, CT, USA) in 2 mL of 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Cat. No.11836153001; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Tissue lysates were centrifuged at 350 x g for 5 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant was collected and transferred to Vivaspin® 2 polyethersulfone tubes (VS0212; Sartorius Stedim Lab Ltd, Stonehouse, Gloucestershire, UK). The Vivaspin® 2 tubes were centrifuged at 4,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The protein concentration of the resulting lysates was determined using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Duplicate cell lysates were obtained in each case.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays

The concentrations of TP53 and pS6 were measured in the chorioamniotic membrane tissue lysates (n=7–9 per group, Table 1) using specific and sensitive immunoassays (p53 pan ELISA Kit from Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Pleasanton, California, USA; and pS6 Sandwich ELISA Kit from Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), following the manufacturers’ instructions. The sensitivity of the assay for TP53 was <9 pg/mL. The sensitivity of the assay for pS6 was within the range recommended by the manufacturer.

Immunohistochemistry

Samples of the chorioamniotic membranes collected from each study group (n=6–8 per group, Table 1) were included. Five-μm-thick sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens were cut and mounted on SuperFrost™ Plus microscope slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunohistochemistry staining for TP53 (anti-human TP53 antibody; Cat. No. M7001, Clone DO-7; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and cyclooxygenase (COX) 2 (anti-Cox2 antibody; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) were performed using a Leica Bond Max automatic staining system (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The Bond™ Polymer Refine Detection Kit (Leica Microsystems) was used to detect the chromogenic reaction of horseradish peroxidase. Isotypes were used as negative controls. Following staining, tissue slides were scanned and the mean intensity of COX2 (a semi-quantitative method of analysis) was determined using a Pannoramic MIDI Digital Slide Scanner (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Activity

Cells positive for SA-β-gal were identified in the chorioamniotic membranes (n=7–11 per group, Table 1) based on a previously described method 24. Chorioamniotic membranes were frozen in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T Compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA, USA). Ten-micrometer-thick cryosections were cut using a Leica CM3050 cryostat (Leica Biosystems) and placed onto Superfrost Plus microscope slides. After fixation with 0.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 1X PBS (pH 5.5), the slides were washed twice in 1 mmol/L of magnesium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich®) in 1X PBS (pH 6.0) for 5 minutes each. Slides were then incubated in a staining solution containing 1 mg/mL of X-gal (Sigma-Aldrich®), 1 mmol/L of magnesium chloride, 5 mmol/L of potassium ferricyanide (Sigma-Aldrich®), and 5 mmol/L of potassium ferrocyanide (Sigma-Aldrich®) in 1X PBS (pH 6.0) for 24 hours at 37° C. After incubation, the slides were washed twice with 1 mmol/L of magnesium chloride in 1X PBS (pH 7.4), followed by an additional 30-minute wash with tap water to remove any precipitate from the staining solution. Slides were dehydrated with a graded ethanol bath (80%, then 95%, then 100%), counterstained with eosin, mounted with xylene, and coverslipped by Tissue-Tek® SCA (Sakura Finetek USA). A Pannoramic MIDI Digital Slide Scanner (PerkinElmer) was used to assess the intensity of senescence-associated-β-galactosidase staining (a semi-quantitative method of analysis).

Immunoblotting of pS6

Chorioamniotic membrane tissue lysates (25 μg per well, n=6–7 per group, Table 1) were subjected to 4–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After electrophoresis, separated proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Next, the membranes were blocked with StartingBlock™ T20 (TBS) Block Buffer (Thermo Fisher) and incubated overnight at 4°C with an anti-human pS6 (S235/236) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). A horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Catalog # 7076S, Cell Signaling Technology) was used as a secondary antibody. Chemiluminescence signals were detected with ChemiGlow® West Reagents (Protein Simple, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and images were acquired using the FUJIFILM LAS-4000 Imaging System (FUJIFILM North America Corporation, Valhalla, NY, USA). Finally, nitrocellulose membranes were stripped with Restore™Plus Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 15 min, washed with 1X PBS, blocked, and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with a mouse anti-β-actin (ACTB) monoclonal antibody (Catalog # A5316, Clone AC-74, Sigma Aldrich). Chemiluminescence signals were again detected with ChemiGlow® West Reagents, and images were acquired using the FUJIFILM LAS-4000 Imaging System.

Relative Determination of Telomere Length

Genomic DNA extraction from frozen chorioamniotic membrane samples (n=15–22 per group, Table 3) was performed with a DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of two different individuals (one was 25 years old and the second one was 52 years old) was isolated using a DNeasy Blood Kit (Qiagen) and used for the validation of the method. Genomic DNA from the PBMCs of four individuals was also isolated and pooled to be used as reference DNA. DNA concentrations and purity were assessed with the NanoDrop™ 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Relative telomere length was measured in the isolated genomic DNA from the chorioamniotic membranes or PBMCs using a previously described PCR method 45 with minor modifications. All qPCRs were performed using the ABI 7500 FAST Real-Time PCR System. The primers (hereafter referred to as “Primer Set#1”) used to amplify the telomere region were the following: forward (5′-GGTTTTTGAGGGTGAGGGTGAGGGTGAGGGTGAGGGT-3′) (270nM) and reverse (5′-TCCCGACTATCCCTATCCCTATCCCTATCCCTATCCCTA-3′) (900nM). A single copy reference gene, 36B4, was amplified using the following primers: forward (5′-CAGCAAGTGGGAAGGTGTAATCC-3′) (300nM) and reverse (5′-CCCATTCTATCATCAACGGGTACAA-3′) (500nM). Each qPCR reaction contained 12.5 μL of 2× SYBR Green PCR master mix (Cat#4309155, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1.25 μL of each forward and reverse primer, and 10 μL of genomic DNA (2ng/μL), which yielded a 25 μL reaction and was run in triplicates. The thermal cycling profile for the telomere region qPCR began at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 30 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, and at 54°C for 2 minutes. For the 36B4 qPCR, the thermal cycling profile began at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 30 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, and at 58°C for 1 minute. A standard curve ranging from 0.63 to 14.17 ng/μL was prepared with reference DNA using serial dilutions (1.68 fold each). Standard curve and reference DNA were included in each qPCR run (telomere region and 36B4). Cycle threshold (Ct) values for telomere region signals (T) and 36B4 signals (S) were generated with the ABI 7500 Fast System SDS version 1.3 software (Applied Biosystems). The formula to calculate the T/S ratio for each sample is: [2Ct(telomeres)/2 Ct(36B4)]−1= 2−ΔCt. The relative telomere length of each sample was calculated as follows: the T/S ratio of each sample relative to the T/S ratio of the reference sample (2−(ΔCt(sample)- ΔCt(reference))= 2−ΔΔCt)45.

Relative telomere length was also measured in the same samples using a different qPCR method and primers 34, 46. The primers (hereafter referred to as “Primer Set#2”) used to amplify the telomere region were the following: forward (5′-CGG TTTGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTT-3′) (200nM) and reverse (5′-GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCT-3′) (200nM). The single copy reference gene, β-Globin (HBG), was amplified using the following primers: forward (5′-GCTTCTGACACAACTGTGTTCACTAGC-3′) (200nM) and reverse (5′-CACCAACTTCATCCACGTTCACC-3′) (200nM). Each qPCR reaction included 10 μL of 2× SYBR Green PCR master mix, 2.5 μL each of forward and reverse primer, and 5 μL of genomic DNA (2ng/μL), which yielded a 20 μL reaction that was run in triplicates. The thermal cycling profile for the telomere region qPCR began at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 30 cycles at 95°C for 5 seconds, at 56°C for 10 seconds, and at 72°C for 60 seconds. For the HBG qPCR, the thermal cycling profile began at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 30 cycles at 95°C for 5 seconds, at 58°C for 10 seconds, and at 72°C for 40 seconds. A standard curve ranging from 0.625 to 20 ng/μL was prepared with reference DNA using serial dilutions (2 fold each). Standard curve and reference DNA were included in each qPCR run (telomere region and HBG). Ct values for telomere signals (T) and HBG signals (S) were generated with the ABI 7500 Fast System SDS version 1.3 software. The formula to calculate the T/S ratio for each sample is [2Ct(telomeres)/2 Ct(HBG)]−1= 2−ΔCt. The relative telomere length of each sample was calculated as follows: the T/S ratio of each sample relative to the housekeeping genes the T/S ratio of the reference sample (2−(ΔCt(sample)- ΔCt(reference))= 2−ΔΔCt).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical data were analyzed using SPSS v.19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For the RT-qPCR senescence-associated gene expression array and RT-qPCR validation, gene expressions relative to the housekeeping genes ACTB/GAPDH/RLP0 and ACTB were calculated as −ΔCt values, respectively. ΔCt (ΔCt= Cttarget -Ctreference) was computed for each sample after averaging the Ct values over the technical replicates. A heat map was created for the group mean expression matrix (gene 3 group mean) with each gene expression level being standardized first. To determine protein-protein interactions, including direct (physical) and indirect (functional) associations, a STRING network was created using the STRING database (http://string-db.org) 47. Hierarchical clustering on genes was applied on the group mean expressions using 1-Pearson correlation as distance metric and average linkage 48. Group means of gene expression were then compared using t tests from an analysis of variance linear model and the resulting P values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. All expression analyses were performed in the R statistical computing environment (http://www.R-project.org/). ELISA, immunohistochemistry, senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining, and immunoblotting data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis tests, followed by Mann-Whitney U tests. Telomere length data were analyzed by t tests using the SPSS v.19.0 software. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the three study populations are displayed in Tables 1–3. None of the chorioamniotic membrane samples used in this study had acute histologic chorioamnionitis (Tables 1–3). In order to confirm that the chorioamniotic membranes underwent the process of labor, we first evaluated the expression of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 [PTGS2 or cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2)], which plays a critical role in the initiation of parturition and therefore is considered a marker of labor49–60. As expected, the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous labor at term or spontaneous preterm labor had a greater expression of COX2 compared to their non-labor counterparts (Supplementary Figure 1).

Expression of senescence-associated genes in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm or term labor

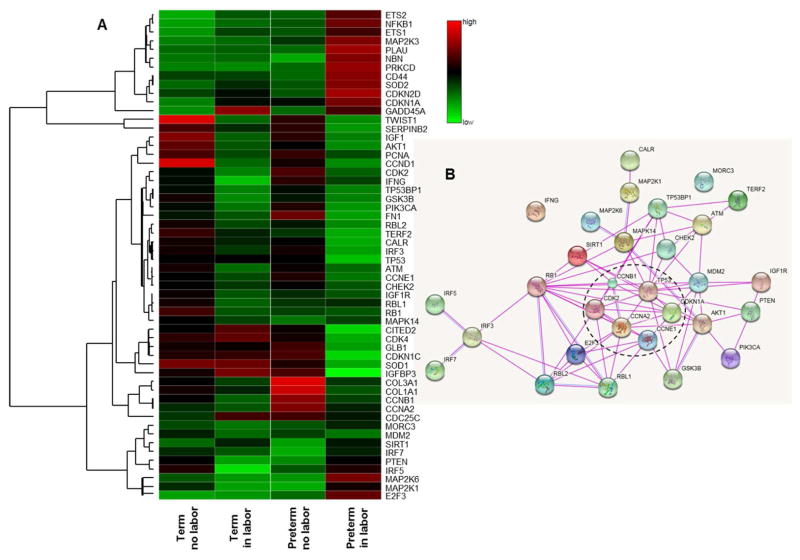

First, we determined whether the expression profile of several senescence-associated genes in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent the process of preterm or term labor was different compared to gestational-age-matched non-labor controls. At first glance, we noticed that the labor groups (term in labor and preterm in labor) displayed different senescence-associated gene profiles compared to the non-labor groups (term no labor and preterm no labor); yet, there were differences between the term in labor and preterm in labor groups (Figure 1A). Thirty differentially expressed genes between the labor (term in labor and preterm in labor) and non-labor (term no labor and preterm no labor) groups were selected. Next, we performed a functional protein association network analysis of these 30 differentially expressed genes between groups, which uncovered that a cluster of these genes were involved in the cell cycle, including the TP53 pathway (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Quantitative RT-qPCR array of senescence-associated genes in the chorioamniotic membranes. A) A heat map visualization of senescence-associated genes in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor (n = 9) or labor at term (n = 8). Gestational age-matched non-labor controls were also included (n = 8 each). B) A STRING network analysis displaying protein-protein associations. Lines between nodes represent known interactions from experimental data (magenta lines) and homologies (blue lines) between the proteins encoded by the differentially expressed genes between the four study groups (term no labor, term in labor, preterm no labor and preterm in labor). Genes selected for RT-qPCR validation are included in a dotted ellipse.

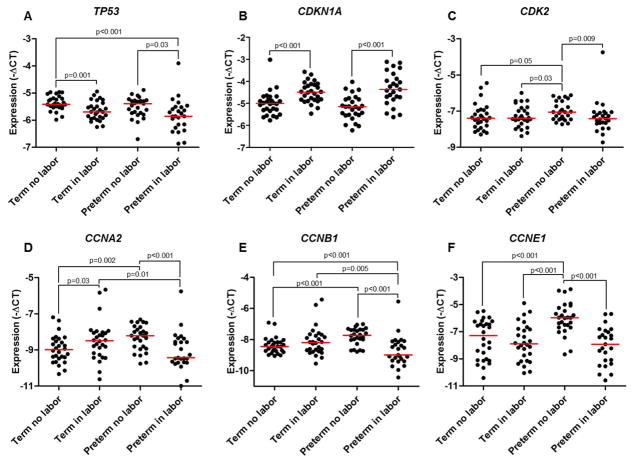

Six of the differentially expressed genes were validated by RT-qPCR using a larger number of samples (Figure 1B). The expression of TP53 was lower in the term in labor group and the preterm in labor group compared to their non-labor counterparts, but no differences were found between the term in labor and preterm in labor groups (Figure 2A). In contrast, the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A) was greater in the term in labor and preterm in labor groups compared to the non-labor controls, and once again, no differences were observed between the term in labor and preterm in labor groups (Figure 2B). Consistently, the expression of CDK2 (Figure 2C), CCNA2 (Figure 2D), CCNB1 (Figure 2E), and CCNE1 (Figure 2F) was reduced in the preterm in labor group compared to the preterm no labor group, but no differences were observed between the term in labor and term no labor groups. In addition, the expression of CCNA2 and CCNB1 was lower in the preterm in labor group than in the term in labor group (Figures 2D and 2E).

Figure 2.

Quantitative RT-qPCR validation of senescence-associated genes in the chorioamniotic membranes. mRNA expression of TP53 (A), CDKN1A (B), CDK2 (C), CCNA2 (D), CCNB1(E), and CCNE1 (F) in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor (n = 26) or labor at term (n = 28). Gestational age-matched non-labor controls were also included (n = 27–28 each). Relative gene expressions are presented as −ΔCt values and are relative to ACTB.

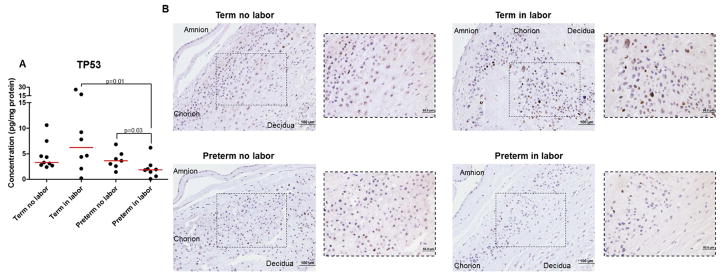

The mRNA and protein expression of TP53 is reduced in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor

The TP53 pathway is a central regulator in the process of cellular senescence1, 2 and the uterine deletion of the Trp53 gene induces spontaneous preterm labor 13, 25, 26, 61. Since TP53 was down-regulated in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor or spontaneous labor at term, we next evaluated whether the protein concentration and immunoreactivity of TP53 was different among the study groups. The concentration of TP53 was reduced in the preterm in labor group compared to the preterm no labor and term in labor groups (Figure 3A). However, no differences were observed in the concentration of TP53 between the term no labor and term in labor groups (Figure 3A). Consistently, immunohistochemistry revealed that the immunoreactivity of TP53 was enhanced in the term in labor group compared to the term no labor, preterm no labor, and preterm in labor groups (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Protein concentration and immunohistochemistry for TP53 in the chorioamniotic membranes. A) Protein concentrations of TP53 in chorioamniotic membrane lysates from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor (n = 8) or labor at term (n = 8). Gestational age-matched non-labor controls were also included (n = 7–9 each). B) Representative images and their magnifications for TP53 in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor (n=6) or labor at term (n=6). Gestational age-matched non-labor controls were also included (n=9–10). 20x and 40x magnifications.

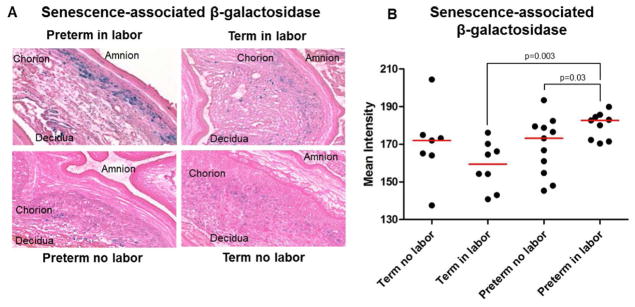

The activity of senescence-associated β-galactosidase is increased in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor

A strong biomarker for senescence is increased lysosomal activity, which is evidenced by the detection of pH-sensitive SA-β-gal24. Indeed, enhanced SA-β-gal activity is a common marker of cellular senescence in both human33, 62 and murine13, 25, 37, 61, 62 placental tissues. We determined the SA-β-gal activity in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor or spontaneous labor at term (Figure 4A). The SA-β-gal activity was increased in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor compared to those who delivered preterm in the absence of labor or those who delivered at term (Figure 4A and 4B). The SA-β-gal activity was mainly observed in the chorion laeve, including mostly trophoblast cells (Figure 4A). No differences were observed in the SA-β-gal activity between the chorioamniotic membranes obtained from women who underwent spontaneous labor at term and those who delivered at term in the absence of labor (Figure 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity in the chorioamniotic membranes. Representative images (A) and semi-quantification (B) of senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor (n = 9) or labor at term (n = 8). Gestational age-matched non-labor controls were also included (n = 7–11 each). 20x magnification.

The expression of pS6 in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm or term labor

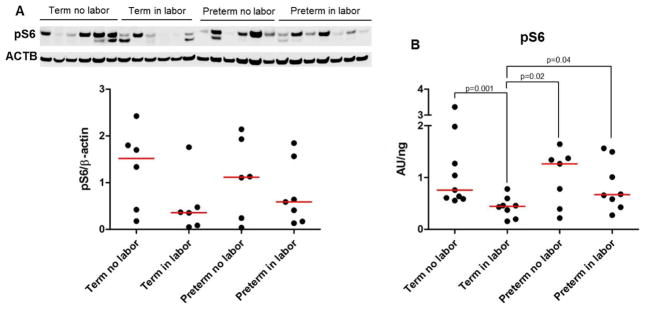

An increase in pS6 levels is observed in the uterus and decidua of pregnant mice with a uterine-specific deletion of Trp53, which display uterine/decidual senescence and deliver prematurely25. Next, we evaluated the expression of pS6 in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor or spontaneous labor at term, using immunoblotting (Figure 5A) and ELISA (Figure 5B). The semi-quantitative approach (i.e. immunoblotting) revealed that the chorioamniotic membranes contained pS6; yet, no statistical differences were observed among the groups (term no labor, term in labor, preterm no labor and preterm in labor; Figure 5A). When a quantitative approach (ELISA) was used, the concentration of pS6 was lower in the term in labor group compared to the term no labor group (Figure 5B). No differences were observed in the pS6 concentration between the preterm in labor and preterm no labor groups (Figure 5B). In addition, the concentration of pS6 was greater in the preterm groups, regardless of the presence of labor, compared to the term in labor group (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Concentration of pS6 in the chorioamniotic membranes. A) Immunoblotting and semi-quantification of pS6 in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor (n = 7) or labor at term (n = 6). Gestational age-matched non-labor controls were also included (n = 6 each). ACTB was used as a loading control. B) Protein concentrations of pS6 in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor (n = 8) or labor at term (n = 8). Gestational age-matched non-labor controls were also included (n = 7–9 each).

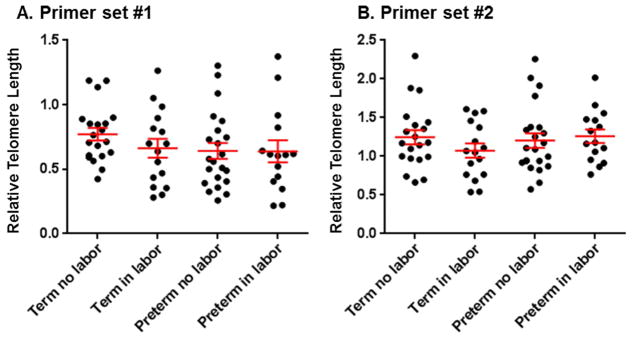

The relative telomere length in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm or term labor

A shorter telomere length was found in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent pPROM63 and in those who underwent spontaneous labor at term35. In both scenarios, such a characteristic has been considered a marker of cellular senescence35, 63. Relative telomere length was determined using two established methods34, 45, 46 in the chorioamniotic membranes from the four study groups. The validation of the relative telomere length methods showed that both sets of primers are able to detect senescent cells: the older individual had a shorter telomere length than the younger individual (Supplementary Figure 2). However, neither method was capable of detecting significant differences in the relative telomere length in the chorioamniotic membranes among the study groups (term no labor, term in labor, preterm no labor, and preterm in labor; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relative telomere length in the chorioamniotic membranes. Relative telomere length in the chorioamniotic membranes using two sets of primers [primer set #1 (A) and primer set #2 (B)] from women underwent spontaneous preterm labor (n =15) or labor at term (n =16). Gestational age-matched non-labor controls were also included (n = 20–22 each).

For the readers’ convenience, a summary of the results is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Signs of cellular senescence in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm or term labor without acute histologic chorioamnionitis

| Sign of Cellular Senescence | Term in labor (vs. Term no labor) | Preterm in labor (vs. Preterm no labor) |

|---|---|---|

| mRNA expression of Tp53 | ↓ | ↓ |

| Protein concentration of TP53 | = | ↓ |

| mRNA expression of CDKN1A | ↑ | ↑ |

| mRNA expression of CDK2 | = | ↓ |

| mRNA expression of CCNA2 | ↑ | ↓ |

| mRNA expression of CCNB1 | = | ↓ |

| mRNA expression of CCNE1 | = | ↓ |

| Senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity | = | ↑ |

| pS6 concentrations | ↓ | = |

| Relative Telomere Length | = | = |

COMMENT

Principal findings

In the chorioamnionitic membranes without acute histologic chorioamnionitis: 1) the mRNA expression profile of senescence-associated genes was different between the labor groups (term in labor and preterm in labor) and the non-labor groups (term no labor and preterm no labor); yet, there were differences between the term in labor and preterm in labor groups; 2) most of the differentially expressed genes among groups were involved in the cell cycle, including the TP53 pathway; 3) the expression of TP53 was down-regulated in the term in labor and preterm in labor groups compared to their non-labor counterparts; 4) the expression of CDKN1A (gene encoding for p21) was up-regulated in the term in labor and preterm in labor groups compared to their non-labor counterparts; 5) the expression of CDK2, CCNA2, CCNB1, and CCNE1 was down-regulated in the preterm in labor group compared to the preterm no labor group; 6) the concentration of TP53 was lower in the preterm in labor group than in the preterm no labor and term in labor groups; 7) the SA-β-gal activity was greater in the preterm in labor group than in the preterm no labor and term in labor groups; 8) the concentration of pS6 was reduced in the term in labor group compared to its non-labor counterpart, but no differences were observed between the preterm in labor and preterm no labor groups; and 9) no significant differences were observed in the relative telomere length among the study groups (term no labor, term in labor, preterm no labor, and preterm in labor. These results suggest that, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, signs of cellular senescence are present in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor compared to those who delivered preterm in the absence of labor. However, the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous labor at term did not show consistent signs of cellular senescence in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis. Collectively, these results suggest that different pathways are implicated in the pathological and physiological processes of labor.

Tumor suppressor protein 53 (TP53) is dysregulated in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor

TP53 is a complex protein that plays a range of critical roles in the regulation of cell cycle progression, apoptosis, senescence, autophagy, metastasis and metabolism64, 65. Female reproductive tissues require an accumulation of TP53 in the absence of stress66. In the decidua, the accumulation of TP53 serves as a “guardian of the genome,” which grows during pregnancy to accommodate the developing fetus66, 67. Consequently, Trp53 null mice (Trp53−/− mice) have impaired implantation68, and the surviving Trp53−/− pups, especially females, die due to the development of exencephaly69. More recently, it was demonstrated that mice with a uterine-specific deletion of Trp53 display uterine senescence and that more than 50% of them delivered premature neonates13. In the study herein, we found that, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, both the mRNA expression and concentration of TP53 were reduced in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor compared to those who delivered preterm in the absence of labor. These data indicate that, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, the transcription and translation of TP53 are dysregulated in the chorioamnionitic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor. The chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous labor at term had a reduced TP53 mRNA abundance, but not TP53 protein concentration, compared to those from women who delivered at term without labor. Together, these data suggest that the TP53 pathway is required throughout gestation25, 66, 67, and its dysregulation can lead to the pathological process of preterm.

The mRNA expression of CDKN1A (gene encoding for p21) and CDK2 is down-regulated in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor

Upon activation, TP53 can transcriptionally regulate p21 (encoded by the CDKN1A gene) that, in turn, suppresses CDK2-mediated retinoblastoma (Rb) 1 inactivation, subsequently preventing S-phase entry and inducing cell cycle arrest70–72. In addition to growth arrest, p21 can mediate cellular senescence through TP53-dependent and -independent pathways73, 74. In the TP53-dependent pathway, p21 acts as a “genome guardian” 75. The activation of the TP53/p21 pathway can either trigger a temporary G1 cell cycle arrest or lead to a chronic state of senescence or apoptosis75. Moreover, p21 can mediate cellular senescence by a reactive oxygen species-based mechanism, which does not require either proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) binding or the CDK inhibitory functions76. Altogether, these data provide evidence that p21 is a negative regulator of the cell cycle and induces cellular senescence or apoptosis in response to many stimuli73.

Previous studies demonstrated that a uterine-specific deletion of Trp53 causes an increase of p21 in the decidua compared to controls13. In addition, the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor with pPROM have an increased expression of p21, as well as display markers of senescence, compared to those from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor with intact membranes77–79. Herein, we showed that the expression of CDKN1A (gene encoding for p21) was up-regulated in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm or term labor without acute histologic chorioamnionitis. However, the expression of CDK2 was down-regulated solely in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor. These results show that, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, the p21 pathway is dysregulated in the chorioamnionitic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor, which likely induces the down-regulation of CDK2 in these tissues. The chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous labor at term had a reduced mRNA expression of CDKN1A, but not CDK2, compared to those from women who delivered at term without labor. These data suggest that during the physiological process of labor at term the p21 pathway is partially dysregulated in the chorioamniotic membranes.

The mRNA expression of CCNA2, CCNB1 and CCNE1 is down-regulated in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor

The cyclins are a family of proteins that, together with their partners the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), comprise the basic components of the machinery that regulate the cell cycle80. In the current study, we found that, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, the mRNA expression of the cyclins CCNA2, CCNB1, and CCNE1 were down-regulated in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor compared to those who delivered preterm in the absence of labor. The cyclin CCNA2 is ubiquitously expressed in all proliferating cells and up-regulated in several cancers81, 82, and is considered to be critical for the mammalian S-phase of the cell cycle81, 83, 84; yet, it is expressed in both the S-85, 86 and G2-87 phases. Consequently, a targeted mutation of the murine Ccna2 gene results in early embryonic lethality at the peri-implantation stage88. The cyclin CCNB1 forms a complex with CDK1, a key regulator of mitotic entry 89. Indeed, a reduction in CCNB1 levels can trigger DNA damage-induced senescence89. Perhaps not surprisingly then, a loss of function of the Ccnb1 gene causes early embryonic lethality90. Lastly, the cyclin CCNE1 forms an active complex with CDK291, which regulates the phosphorylation and follows dissociation of Rb from the inactive Rb-E2F complex92, 93. Therefore, the deregulation of CCNE1 can contribute to tumorigenesis94. Taken together, these data suggest that a dysregulation of the cyclin family, as well as the cyclin-dependent kinases, induces cell cycle arrest in the chorioamnionitic membranes, which leads to cellular senescence during the pathological process of preterm labor in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis.

The activity of senescence-associated β-galactosidase is increased in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor

Cellular senescence is characterized by an increase in lysosomal activity due to the increased synthesis and reduced degradation of proteins95. One of the lysosomal enzymes that exhibits an increased activity in senescent cells is β-galactosidase, and therefore termed senescence-associated β-galactosidase or SA-β-gal24. The SA-β-gal activity is elevated in mice with a uterine-specific deletion of Trp53 that deliver preterm13. In addition, the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent preterm labor with pPROM have a higher SA-β-gal activity than those from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor with intact membranes77. Herein, we found that, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis and pPROM, the SA-β-gal activity was increased in the chorioamniotic membranes, mostly in the chorion, from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor compared to those who delivered preterm in the absence of labor. These data are consistent with previous reports demonstrating that the chorion layer of the fetal membranes can exhibit SA-β-gal activity33, 77. In addition, mice with a uterine-specific deletion of Trp53 show an increased SA-β-gal activity in the decidual tissues (homologous to the decidua basalis in humans)13. Since the current study only evaluated the decidua parietalis (attached to the chorioamnionitic membranes) and not the decidua basalis (attached to the placenta), we suggest that, in human preterm labor, cellular senescence occurs in trophoblast cells rather than in the decidua parietalis. Further studies are required to investigate whether the SA-β-gal activity, or any other cellular senescence marker, is observed in the decidua basalis of women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor.

The concentration of pS6 in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor

pS6 kinase is involved in the phosphorylation of multiple substrates96 and its phosphorylation can result from the activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway96. The concentration of pS6 is increased in senescent cells and decreased in quiescent cells97. The levels of pS6 in senescent cells can be comparable to those of proliferating cells; therefore, senescent cells can resemble proliferating cells in some cases97. The fact that mice with a uterine-specific deletion of Trp53 deliver preterm and have high levels of pS625 prompted us to hypothesize that the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor would have increased concentrations of pS6. Contrary to this hypothesis, we found that, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, the concentration of pS6 did not change between the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor and those from women who delivered preterm in the absence of labor. Although we cannot discard the possibility that the levels of pS6 in vivo are different to those reported herein since sample preservation may alter the levels of this protein, these data imply that the process of cellular senescence in preterm labor is different between the human chorioamniotic membranes and murine decidual tissues.

Telomere length-independent cellular senescence in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor

Telomeres are repetitive sequences of DNA (tandem TTAGGG repeats) present at the end of linear chromosomes containing a C-rich lagging strand and a G-rich leading strand98, 99. In the absence of protective mechanisms for telomeres, linear chromosomes shorten progressively with every cycle of DNA replication, ultimately leading to cellular senescence or apoptosis98, 100. One mechanism capable of elongating telomeres includes the ectopic expression of the enzyme telomerase, which lessens telomere shortening generated during cell division and evades cellular senescence101. Upon exposure to mild oxidative stress, cells reduce their replicative capacity and exhibit telomere shortening, which is thought to represent cellular senescence102–113. Telomere shortening has been observed in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous labor at term35 and in those from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor with pPROM114. Herein, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, no differences were observed in the telomere length between the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm or term labor and those from women who delivered preterm or term in the absence of labor. Although telomere shortening has been considered a marker of cellular senescence, recent reports now suggest that telomere dysfunction can also occur in a length-independent manner99. Therefore, we propose that the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis are a biological example in which senescence markers are observed in a telomere length-independent manner.

Research implications

Decidual senescence has been considered a mechanism of disease for spontaneous preterm labor13, 14 and this process seems to be independent of severe acute inflammation25, 115. Such a concept is largely supported by animal experimentation. Herein, we provided evidence that, in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis (severe acute inflammation), signs of cellular senescence are present in the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous preterm labor. In addition, we showed that the chorioamniotic membranes from women who underwent spontaneous labor at term did not display consistent signs of cellular senescence in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis, suggesting that different pathways are implicated in the pathological and physiological processes of labor.

A central question that needs to be addressed is: what are the mechanisms whereby cellular senescence in the chorioamniotic membranes leads to spontaneous preterm labor in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis? We propose that the chorioamniotic membranes that display cellular senescence release damage-associated molecular patterns or alarmins which, in turn, can initiate immune responses and lead to the pathological process of preterm labor116–118.

Strengths and limitations

The current study represents the first evidence in humans that cellular senescence is implicated in the mechanisms that lead to spontaneous preterm labor in the absence of acute histological chorioamnionitis. Herein, we also showed that the physiological process of labor at term may not be characterized by signs of cellular senescence in the chorioamniotic membranes. Cellular senescence has also been observed in the placentas of women with unexplained stillbirth114, 119, pPROM114, fetal growth restriction120, and placenta accreta111. Therefore, cellular senescence may be implicated in placental pathological processes.

A limitation of the current study is its descriptive nature since it does not allow the establishment of the timing for the development of cellular senescence. A second limitation is that most of the preterm no labor samples were collected from women with pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, which could interfere with the cellular senescence determinations. Yet, the preterm no labor samples had similar cellular senescence levels to the term no labor samples, which were collected from women without pregnancy complications. A third limitation is the modest number of samples used for some of the determinations (immunohistochemistry, immunoblotting, ELISA, and SA-β-galactosidase activity), which was due to the rigid inclusion criteria (absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis) utilized in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This research was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS), and, in part, with federal funds from the NICHD/NIH/DHHS under Contract No. HHSN275201300006C. This research was also supported by the Wayne State University Perinatal Initiative in Maternal, Perinatal and Child Health. S.K.D. was supported by the March of Dimes grants (21-FY12-127 and 22-FY13-543).

We gratefully acknowledge Yang Jiang, Derek Miller, Zhong Dong, Zhonghui Xu, and Samuel Handelman for their contributions to the execution of this study. We thank the physicians and nurses from the Center for Advanced Obstetrical Care and Research and the Intrapartum Unit for their help in collecting human samples. We also thank staff members of the PRB Clinical Laboratory and the PRB Histology/Pathology Unit for the processing and examination of the pathological sections. Finally, we thank Tara N Mial for her critical readings of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Paper Presentation Information: Presented in part at the 62nd Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Reproductive Investigation, 25-28th March 2015, San Francisco, CA, USA

Disclaimer for authors employed by the U.S. Federal Government: Dr. Roberto Romero has contributed to this work as part of his official duties as an employee of the U.S. Federal Government

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Van Deursen JM. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature. 2014;509:439–46. doi: 10.1038/nature13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox LS, Redman C. The role of cellular senescence in ageing of the placenta. Placenta. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.01.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho KA, Ryu SJ, Oh YS, et al. Morphological adjustment of senescent cells by modulating caveolin-1 status. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42270–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JH, Hales CN, Ozanne SE. DNA damage, cellular senescence and organismal ageing: causal or correlative? Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7417–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freund A, Laberge RM, Demaria M, Campisi J. Lamin B1 loss is a senescence-associated biomarker. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:2066–75. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-10-0884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox H. Senescence of placental villi. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1967;74:881–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1967.tb15574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin BJ, Spicer SS. Ultrastructural features of cellular maturation and aging in human trophoblast. J Ultrastruct Res. 1973;43:133–49. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(73)90074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burstein R, Frankel S, Soule SD, Blumenthal HT. Aging of the placenta: autoimmune theory of senescence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;116:271–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(73)91062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosso P. Placenta as an aging organ. Curr Concepts Nutr. 1976;4:23–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parmley TH, Gupta PK, Walker MA. “Aging” pigments in term human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;139:760–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parmley T. Placental senescence. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1984;176:127–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4811-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutta EH, Behnia F, Boldogh I, et al. Oxidative stress damage-associated molecular signaling pathways differentiate spontaneous preterm birth and preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2016;22:143–57. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gav074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirota Y, Daikoku T, Tranguch S, Xie H, Bradshaw HB, Dey SK. Uterine-specific p53 deficiency confers premature uterine senescence and promotes preterm birth in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:803–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI40051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science. 2014;345:760–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1251816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero R, Mazor M, Munoz H, Gomez R, Galasso M, Sherer DM. The preterm labor syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;734:414–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero R. Prenatal medicine: the child is the father of the man. Prenatal Neonatal Med. 1996:8–11. doi: 10.1080/14767050902784171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkowitz GS, Blackmore-Prince C, Lapinski RH, Savitz DA. Risk factors for preterm birth subtypes. Epidemiology. 1998;9:279–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moutquin JM. Classification and heterogeneity of preterm birth. BJOG. 2003;110(Suppl 20):30–3. doi: 10.1016/s1470-0328(03)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muglia LJ, Katz M. The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:529–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0904308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379:2162–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton BE, Hoyert DL, Martin JA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2010–2011. Pediatrics. 2013;131:548–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:430–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9363–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirota Y, Cha J, Yoshie M, Daikoku T, Dey SK. Heightened uterine mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling provokes preterm birth in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18073–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108180108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burnum KE, Hirota Y, Baker ES, et al. Uterine deletion of Trp53 compromises antioxidant responses in the mouse decidua. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4568–79. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arenas-Hernandez M, Romero R, St Louis D, Hassan SS, Kaye EB, Gomez-Lopez N. An imbalance between innate and adaptive immune cells at the maternal-fetal interface occurs prior to endotoxin-induced preterm birth. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:462–73. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furcron AE, Romero R, Plazyo O, et al. Vaginal progesterone, but not 17alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate, has antiinflammatory effects at the murine maternal-fetal interface. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:846 e1–46 e19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Y, Romero R, Miller D, et al. An M1-like Macrophage Polarization in Decidual Tissue during Spontaneous Preterm Labor That Is Attenuated by Rosiglitazone Treatment. J Immunol. 2016;196:2476–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Arenas-Hernandez M, et al. Intra-amniotic administration of lipopolysaccharide induces spontaneous preterm labor and birth in the absence of a body temperature change. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1287894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velarde MC, Menon R. Positive and negative effects of cellular senescence during female reproductive aging and pregnancy. J Endocrinol. 2016;230:R59–76. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menon R. Human fetal membranes at term: Dead tissue or signalers of parturition? Placenta. 2016;44:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behnia F, Taylor BD, Woodson M, et al. Chorioamniotic membrane senescence: a signal for parturition? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polettini J, Behnia F, Taylor BD, Saade GR, Taylor RN, Menon R. Telomere Fragment Induced Amnion Cell Senescence: A Contributor to Parturition? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menon R, Behnia F, Polettini J, Saade GR, Campisi J, Velarde M. Placental membrane aging and HMGB1 signaling associated with human parturition. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8:216–30. doi: 10.18632/aging.100891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonney EA. Mapping out p38MAPK. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017:77. doi: 10.1111/aji.12652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonney EA, Krebs K, Saade G, et al. Differential senescence in feto-maternal tissues during mouse pregnancy. Placenta. 2016;43:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malak TM, Bell SC. Structural characteristics of term human fetal membranes: a novel zone of extreme morphological alteration within the rupture site. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:375–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1994.tb11908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLaren J, Malak TM, Bell SC. Structural characteristics of term human fetal membranes prior to labour: identification of an area of altered morphology overlying the cervix. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:237–41. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nhan-Chang CL, Romero R, Tarca AL, et al. Characterization of the transcriptome of chorioamniotic membranes at the site of rupture in spontaneous labor at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:462 e1–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gomez-Lopez N, Vadillo-Perez L, Hernandez-Carbajal A, Godines-Enriquez M, Olson DM, Vadillo-Ortega F. Specific inflammatory microenvironments in the zones of the fetal membranes at term delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:235 e15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American College Of O, Gynecology Committee On Practice B-O. Acog Practice Bulletin Number 49, December 2003: Dystocia and augmentation of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1445–54. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim CJ, Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, Chaiyasit N, Yoon BH, Kim YM. Acute chorioamnionitis and funisitis: definition, pathologic features, and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:S29–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Redline RW. Classification of placental lesions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:S21–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alhusseini NF, Madboly AG. Telomere Length Measurement by Quantitative Real-time PCR: A Molecular Marker for Human Age Prediction. American Journal of Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2016;12:64–71. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romero R, Emamian M, Quintero R, Wan M, Hobbins JC, Mitchell MD. Amniotic fluid prostaglandin levels and intra-amniotic infections. Lancet. 1986;1:1380. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romero R, Emamian M, Wan M, Quintero R, Hobbins JC, Mitchell MD. Prostaglandin concentrations in amniotic fluid of women with intra-amniotic infection and preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1461–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romero R, Wu YK, Mazor M, Hobbins JC, Mitchell MD. Amniotic fluid prostaglandin E2 in preterm labor. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1988;34:141–5. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(88)90137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell MD, Edwin S, Romero RJ. Prostaglandin biosynthesis by human decidual cells: effects of inflammatory mediators. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1990;41:35–8. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(90)90128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitchell MD, Romero RJ, Avila C, Foster JT, Edwin SS. Prostaglandin production by amnion and decidual cells in response to bacterial products. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1991;42:167–9. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(91)90152-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishihara O, Numari H, Saitoh M, et al. Prostaglandin E2 production by endogenous secretion of interleukin-1 in decidual cells obtained before and after the labor. Prostaglandins. 1996;52:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(96)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fuentes A, Spaziani EP, O’Brien WF. The expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in amnion and decidua following spontaneous labor. Prostaglandins. 1996;52:261–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(96)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slater D, Allport V, Bennett P. Changes in the expression of the type-2 but not the type-1 cyclo-oxygenase enzyme in chorion-decidua with the onset of labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:745–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Erkinheimo TL, Saukkonen K, Narko K, Jalkanen J, Ylikorkala O, Ristimaki A. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and prostanoid receptors by human myometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3468–75. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sawdy RJ, Slater DM, Dennes WJ, Sullivan MH, Bennett PR. The roles of the cyclo-oxygenases types one and two in prostaglandin synthesis in human fetal membranes at term. Placenta. 2000;21:54–7. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sooranna SR, Lee Y, Kim LU, Mohan AR, Bennett PR, Johnson MR. Mechanical stretch activates type 2 cyclooxygenase via activator protein-1 transcription factor in human myometrial cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:109–13. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee DC, Romero R, Kim JS, et al. Evidence for a spatial and temporal regulation of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 expression in human amnion in term and preterm parturition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:E86–91. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deng W, Cha J, Yuan J, et al. p53 coordinates decidual sestrin 2/AMPK/mTORC1 signaling to govern parturition timing. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2941–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI87715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cha J, Bartos A, Egashira M, et al. Combinatory approaches prevent preterm birth profoundly exacerbated by gene-environment interactions. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4063–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI70098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Menon R, Yu J, Basanta-Henry P, et al. Short fetal leukocyte telomere length and preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Lertpiriyapong K, et al. Novel roles of androgen receptor, epidermal growth factor receptor, TP53, regulatory RNAs, NF-kappa-B, chromosomal translocations, neutrophil associated gelatinase, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in prostate cancer and prostate cancer stem cells. Adv Biol Regul. 2016;60:64–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCubrey JA, Lertpiriyapong K, Fitzgerald TL, et al. Roles of TP53 in determining therapeutic sensitivity, growth, cellular senescence, invasion and metastasis. Adv Biol Regul. 2017;63:32–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brosens JJ, Gellersen B. Death or survival--progesterone-dependent cell fate decisions in the human endometrial stroma. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;36:389–98. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Albrechtsen N, Dornreiter I, Grosse F, Kim E, Wiesmuller L, Deppert W. Maintenance of genomic integrity by p53: complementary roles for activated and non-activated p53. Oncogene. 1999;18:7706–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu W, Feng Z, Teresky AK, Levine AJ. p53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF. Nature. 2007;450:721–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sah VP, Attardi LD, Mulligan GJ, Williams BO, Bronson RT, Jacks T. A subset of p53-deficient embryos exhibit exencephaly. Nat Genet. 1995;10:175–80. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dulic V, Kaufmann WK, Wilson SJ, et al. p53-dependent inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase activities in human fibroblasts during radiation-induced G1 arrest. Cell. 1994;76:1013–23. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gartel AL, Radhakrishnan SK. Lost in transcription: p21 repression, mechanisms, and consequences. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3980–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johmura Y, Nakanishi M. Multiple facets of p53 in senescence induction and maintenance. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:1550–55. doi: 10.1111/cas.13060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abbas T, Dutta A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:400–14. doi: 10.1038/nrc2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qian Y, Chen X. Tumor suppression by p53: making cells senescent. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25:515–26. doi: 10.14670/hh-25.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Georgakilas AG, Martin OA, Bonner WM. p21: A Two-Faced Genome Guardian. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23:310–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Macip S, Igarashi M, Fang L, et al. Inhibition of p21-mediated ROS accumulation can rescue p21-induced senescence. EMBO J. 2002;21:2180–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dutta EH, Urrabaz-Garza R, Saade GR, Taylor BD, Behnia F, Menon R. Senescence and senescence associated inflammation delineate preterm premature rupture of membranes and spontaneous preterm birth with intact membranes as distinct phenotypes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:S145–S46. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dutta EH, Kacerovsky M, Behnia F, Kechichian T, Saade GR, Menon R. Development of DNA damage foci, loss of Lamin B and activation of pp38MAPK in pPROM: classic signs of senescence in human amniochorion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:S92. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Menon R, Boldogh I, Hawkins HK, et al. Histological evidence of oxidative stress and premature senescence in preterm premature rupture of the human fetal membranes recapitulated in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1740–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wolgemuth DJ. Function of the A-type cyclins during gametogenesis and early embryogenesis. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2011;53:391–413. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-19065-0_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pines J, Hunter T. Human cyclin A is adenovirus E1A-associated protein p60 and behaves differently from cyclin B. Nature. 1990;346:760–3. doi: 10.1038/346760a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang J, Chenivesse X, Henglein B, Brechot C. Hepatitis B virus integration in a cyclin A gene in a hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature. 1990;343:555–7. doi: 10.1038/343555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yam CH, Fung TK, Poon RY. Cyclin A in cell cycle control and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1317–26. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8510-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hochegger H, Takeda S, Hunt T. Cyclin-dependent kinases and cell-cycle transitions: does one fit all? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:910–6. doi: 10.1038/nrm2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Erlandsson F, Linnman C, Ekholm S, Bengtsson E, Zetterberg A. A detailed analysis of cyclin A accumulation at the G(1)/S border in normal and transformed cells. Exp Cell Res. 2000;259:86–95. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Girard F, Strausfeld U, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ. Cyclin A is required for the onset of DNA replication in mammalian fibroblasts. Cell. 1991;67:1169–79. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Swenson KI, Farrell KM, Ruderman JV. The clam embryo protein cyclin A induces entry into M phase and the resumption of meiosis in Xenopus oocytes. Cell. 1986;47:861–70. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Murphy M, Stinnakre MG, Senamaud-Beaufort C, et al. Delayed early embryonic lethality following disruption of the murine cyclin A2 gene. Nat Genet. 1997;15:83–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nakayama Y, Yamaguchi N. Role of cyclin B1 levels in DNA damage and DNA damage-induced senescence. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2013;305:303–37. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407695-2.00007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brandeis M, Rosewell I, Carrington M, et al. Cyclin B2-null mice develop normally and are fertile whereas cyclin B1-null mice die in utero. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4344–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Payton M, Coats S. Cyclin E2, the cycle continues. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:315–20. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Koff A, Cross F, Fisher A, et al. Human cyclin E, a new cyclin that interacts with two members of the CDC2 gene family. Cell. 1991;66:1217–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90044-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ohtsubo M, Theodoras AM, Schumacher J, Roberts JM, Pagano M. Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for the G1-to-S phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2612–24. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Spruck CH, Won KA, Reed SI. Deregulated cyclin E induces chromosome instability. Nature. 1999;401:297–300. doi: 10.1038/45836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]