Abstract

Purpose

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of central visual loss among patients over the age of 55 years worldwide. Neovascular-type AMD (nAMD) accounts for approximately 10% of patients with AMD and is characterized by choroidal neovascularization (CNV). The proliferation of choroidal endothelial cells (CECs) is one important step in the formation of new vessels. Transcriptional coactivator Yes-associated protein (YAP) can promote the proliferation of multiple cancer cells, corneal endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells, which participate in angiogenesis. This study intends to reveal the expression and functions of YAP during the CNV process.

Methods

In the study, a mouse CNV model was generated by laser photocoagulation. YAP expression was detected with western blotting and immunohistochemistry. YAP siRNA and ranibizumab, a VEGF monoclonal antibody, were injected intravitreally in CNV mice. The YAP and VEGF expression levels after injection were detected with western blotting. The incidence and leakage area of CNV were measured with fundus fluorescein angiography, choroidal flat mounting, and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. Immunofluorescent double staining was used to detect YAP cellular localization with CD31 (an endothelial cell marker) antibody. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression in CNV mice without or with YAP siRNA intravitreal injection and the colocalization of PCNA and CD31 were measured with western blotting and immunofluorescent double staining, respectively.

Results

YAP expression increased following laser exposure, in accordance with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression. YAP siRNA and ranibizumab decreased VEGF expression and the incidence and leakage area of CNV. YAP was localized in the vascular endothelium within the CNV site. Additionally, after laser exposure, YAP siRNA inhibited the increased expression of PCNA, which was colocalized with endothelial cells.

Conclusions

This study showed that YAP upregulation promoted CNV formation by upregulating the proliferation of endothelial cells, providing evidence for the molecular mechanisms of CNV and suggesting a novel molecular target for nAMD treatment.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of central visual loss among patients beyond the age of 55 years worldwide. The neovascular (exudative or wet) type (nAMD) accounts for approximately 10% of patients with AMD. nAMD is characterized by choroidal neovascularization (CNV), which is the formation of a choroidal neovascular membrane fibrovascular complex that emanates from the choriocapillaris through a defective Bruch’s membrane. The pathogenesis of CNV is not fully understood, but vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) have been found to play important roles in its development [1]. Among them, VEGF-A can promote the division and proliferation of vascular endothelial cells and neovascularization and maintain the survival of new vessels. Furthermore, VEGF-A is an inflammatory cell chemotactic factor [2,3]. It also increases vascular permeability [4]. High VEGF-A expression can be detected in surgically isolated samples of newly formed vessel membranes associated with nAMD [5]. VEGF inhibition has become a widely accepted treatment for exudative AMD.

Ranibizumab (RBZ, trade name Lucentis) is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody. Its receptor binding site is VEGF-A, which is known to promote vascular generation and leakage and to cause nAMD. The binding of RBZ prevents the interaction of vascular receptors (VEGFR1 and VEGFR2) on the surfaces of vascular endothelial cells, inhibits vascular endothelial hyperplasia, and reduces vascular leakage into the macular region and the development of CNV [6]. In 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of intravitreal RBZ injections for the treatment of nAMD. The State Food and Drug Authority of China approved the clinical use in December 2011. However, RBZ can cause ocular adverse effects (AEs), including conjunctival hemorrhage, eye pain, vitreous floaters, and increased intraocular pressure [7]. Reported serious ocular AEs include endophthalmitis, uveitis, retinal detachment, retinal tear, retinal hemorrhage, and vitreous hemorrhage [8]. Therefore, the identification of new molecular targets of nAMD treatment is extremely urgent.

The proliferation of choroidal endothelial cells (CECs) is one important step in the formation of new vessels [9]. Angiogenic cytokines and growth factors secreted through an autocrine loop by CECs, or by a paracrine loop through the RPE, inflammatory cells, or fibroblasts, modulate the development of CNV [10]. Therefore, the molecules that regulate endothelial cell proliferation during CNV are of interest to researchers.

Yes-associated protein (YAP) or its paralog transcriptional coactivator with a PDZ-binding motif (TAZ; also named WWTR1) is a transcription coactivator in the Hippo pathway [11] and has vital roles in regulating the proliferation, differentiation, and migration of cells, tissue growth, and organ morphogenesis [12]. The Hippo pathway has been established in Drosophila melanogaster as an important regulator of organ size, and this pathway is highly conserved in mammals [13,14]. Studies have demonstrated that the fundamental roles of the Hippo signaling pathway include organ size control, regeneration, stem cell self-renewal, and tumorigenesis [15-17]. Neurofibromin 2 (NF2) knockout mice develop cataracts due to the disorganization and accumulation of cells in the lens epithelium as a result of abnormal tissue growth, which can be reversed by deleting YAP, indicating that this phenotype is dependent on the Hippo pathway [18]. This phenotype aligns with the current understanding of elevated YAP activity resulting in overgrowth, especially in tumors such as ovarian cancer [19], colorectal cancer [20], non-small cell lung cancer [21], and prostate cancer [22]. Interestingly, recent studies showed that YAP/TAZ mediates a wide range of cellular signals, including cell–cell contact, cell polarity, mechanical cues, secreted mitogens, and cellular metabolic status [23], which are all required for the regulation of angiogenesis. In addition, the crucial roles of YAP/TAZ have been uncovered in the morphogenesis, polarization, and migration of tip endothelial cells (ECs) and in the proliferation of stalk ECs in the developing vasculature with respect to the regulation of actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, cell cycle progression, and metabolism [24]. However, the expression and functions of YAP in CNV remain unclear.

Based on previous research, we speculated whether YAP regulated CNV formation by modulating the proliferation of CECs. A mouse CNV model was created by laser exposure, and YAP siRNA intravitreal injection was applied while RBZ was regarded as a positive control. This study further illustrates the cellular and molecular mechanisms of CNV formation and suggests novel molecular targets for AMD treatment.

Methods

Mouse laser-induced CNV

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the requirements of the Animal Welfare committee of Nantong University. The research protocol for the use of animals was approved by the Center of Laboratory Animals, Nantong University (Nantong, Jiangsu, China) and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Visual Research.

Adult C57BL/6J (B6) mice (Experimental Animal Center of Nantong University, Nantong, Jiangsu, China) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with 0.5% pentobarbital (0.1 ml per 10 g weight), and the pupils were dilated with topical administration of tropic amide phenylephrine eye drops (Santen, Osaka, Japan). Laser photocoagulation (647.1 nm; 50 mm spot size; 0.05 s duration; 250 mW) with a hand-held contact fundus lens (Ocular Instruments, Bellevue, WA) was performed to burn the retina at the 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock positions. The time at which a bubble was observed, indicating rupture of Bruch’s membrane, was recorded. All mice were randomly divided into five groups based on the time after laser treatment (normal, 1, 3, 7, and 14 days). For western blot analysis, each group contained 24 mice that received laser treatment, and 15 mice that did not receive laser treatment constituted the control group. In the control and 7 day post-laser groups, another 45 mice (90 eyeballs) were included for choroidal flat mount, immunofluorescence, and histopathology.

Western blotting

RPE-choroid-sclera complexes and retinas were extracted from three mice at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after laser injury. Proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was then incubated with rabbit anti-YAP (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), mouse anti-VEGF (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and mouse anti-PCNA (1:1,000; Chemicon, Temecula, CA). The antibodies were incubated with 5% skim milk overnight at 4 °C and reacted with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2,000; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) at 37 °C for 2 h. Extensive washes in 0.05% Tween-20 in TBS were followed by incubation with anti-GAPDH (1:1,000; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). The blots were then incubated with chemifluorescent reagent enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Thermo Scientific) and exposed to X-ray film in the dark. The intensity of the GAPDH signal was used as an endogenous control, and band optical density was quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Immunohistochemistry

Eight eyes were enucleated in each group, and 8 μm cryosections were prepared for immunohistochemistry staining 7 days after laser photocoagulation. Slides were briefly washed in PBS (136 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2PO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) pH 7.4) and blocked with 3% normal bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h. The sections were incubated sequentially with rabbit anti-YAP (1:200; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), with three PBS washes in between. Immunoreactivity was visualized with the peroxidase substrate amino ethyl carbazole (AEC kit; Hao Yang Biologic, TianJin, China). Images of the tissue samples were acquired with a microscope equipped with epifluorescence (Eclipse E800; Nikon, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) through a digital camera (DS-Fi1c; Nikon).

Intravitreal injection

YAP siRNA (2.5 nmol; Biomics Biotechnologies Co., Ltd, Nantong, China) dissolved in 1 μl of PBS (Sigma Aldrich) and 10 μg of RBZ, an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody (Lucentis; Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA) were injected into the vitreous cavity with a 33-gauge, double-caliber needle (Ito Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) immediately after the laser injury. Mice with or without laser injury were killed on day 7. The normal control group represented no laser injury or intravitreal ranibizumab injection (IVR). The 7 day group represented laser-induced CNV without any injection.

Fundus fluorescein angiography

To confirm the inhibitory effect of YAP siRNA on CNV formation, fluorescein angiography was performed 7 days after laser photocoagulation. The development of CNV was evaluated using a digital fundus camera connected to a slit-lamp delivery system (Heidelberg, Beijing, China), and images were captured 3 min after 0.3 ml of 2% fluorescein sodium (Alcon Laboratories, Irvine, CA) was injected into the intraperitoneal cavity of mice as previously described [25].

Choroidal flat mount

Seven days after laser coagulation, 30 eyes (six eyes from three mice/each group) were subjected to choroidal flat mount. The eyes were enucleated and immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Guoyao Group of Chemical Reagents, Beijing, China) in PBS (pH 7.3) for 1 h. Under a biopsy microscope, the anterior segments were wiped out, and the neurosensory retinas were detached and separated from the optic nerve head. The remaining eyecups were washed with cold immunochemistry (ICC) buffer (0.5% BSA, 0.2% Tween-20, and 0.1% Triton X-100) in PBS. A 1 mg/ml solution of Alexa Fluor 568 conjugated isolectin-B4 (1:100; Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was prepared in ICC buffer. The eyecups were incubated with the fluorescent dyes above in a humidified chamber at 4 °C with gentle shaking for 4 h, followed by washing with cold ICC buffer. Four or five radial cuts were made toward the optic nerve head for flat mounting of the sclera/choroid/RPE complexes with the gel (Gel-mount; Biomedia Corp. Foster City, CA). The samples were covered and sealed for microscopic analysis.

CNV volume quantification

Z-stack images of CNV retinal flatmounts stained with isolectin B4 were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope with a 10X objective lens. The image stacks were rendered in three dimensions using IMARIS imaging software (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland) and processed to digitally extract the fluorescent lesion volume.

Histopathology

Eight eyes were enucleated in each group, and 8 μm cryosections were prepared for hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining 7 days after laser photocoagulation. The sections were coverslipped with mounting medium. Serial sections were examined, and the samples that contained the thickest or widest lesions among the set of specimens obtained for each CNV condition were assessed. Slices with HE staining were examined using a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). IPP 6.0 was used to calculate the maximum thickness and length of each CNV lesion.

Immunofluorescence

YAP tissue localization was examined on 8 μm cryosections (7 days after laser photocoagulation). The cryosections were blocked with 1% BSA for 4 h at room temperature and then incubated with rabbit YAP antibody (1:50; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and mouse CD31 antibody (1:50, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at 4 °C overnight. For CD31 staining, antigen retrieval was achieved using a heated water bath at 97 °C for 10 min. Then, the slides were stained with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and Hoechst 33258 (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: 861405). Photomicrographs were taken using a digital high-sensitivity camera (Hamamatsu, ORCA-ER C4742–95, Hamamatsu, Japan).

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD). A one-way ANOVA was used for statistical comparisons of multiple groups. Descriptive statistics were calculated using Stata statistical software version 11.0. A p value of less than 0.5 was considered statistically significant. Each experiment was performed at least three times.

Results

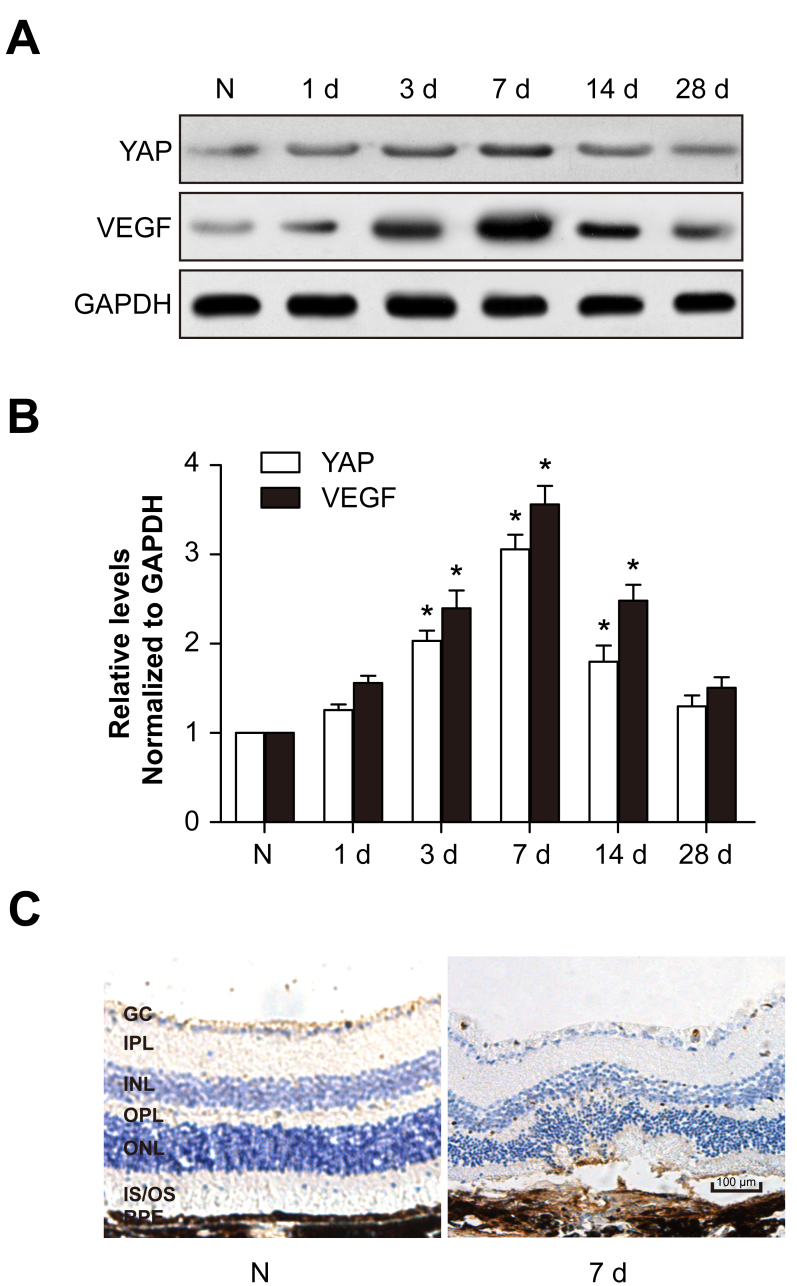

YAP and VEGF expression increases after laser photocoagulation

To identify the expression levels of YAP and VEGF in CNV, proteins of RPE-choroid complexes and retinas were extracted for western blotting. After laser injury, YAP expression was upregulated and peaked at 7 days, showing a similar tendency to that of VEGF (Figure 1A,B). Immunohistochemistry also showed that YAP expression increased following laser exposure (Figure 1C). These results suggest that YAP may be associated with CNV formation.

Figure 1.

YAP and VEGF expression levels are upregulated after CNV formation. The mouse choroidal neovascularization (CNV) model was generated by laser photocoagulation. A: YAP and VEGF protein levels were detected with western blotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. B: The histogram shows the densitometric analysis of the average levels of YAP and VEGF relative to GAPDH. *p<0.05; compared to normal controls. C: Immunohistochemistry of YAP in the normal and 7 day post-laser photocoagulation groups.

YAP siRNA alleviates the leakage and extent of CNV

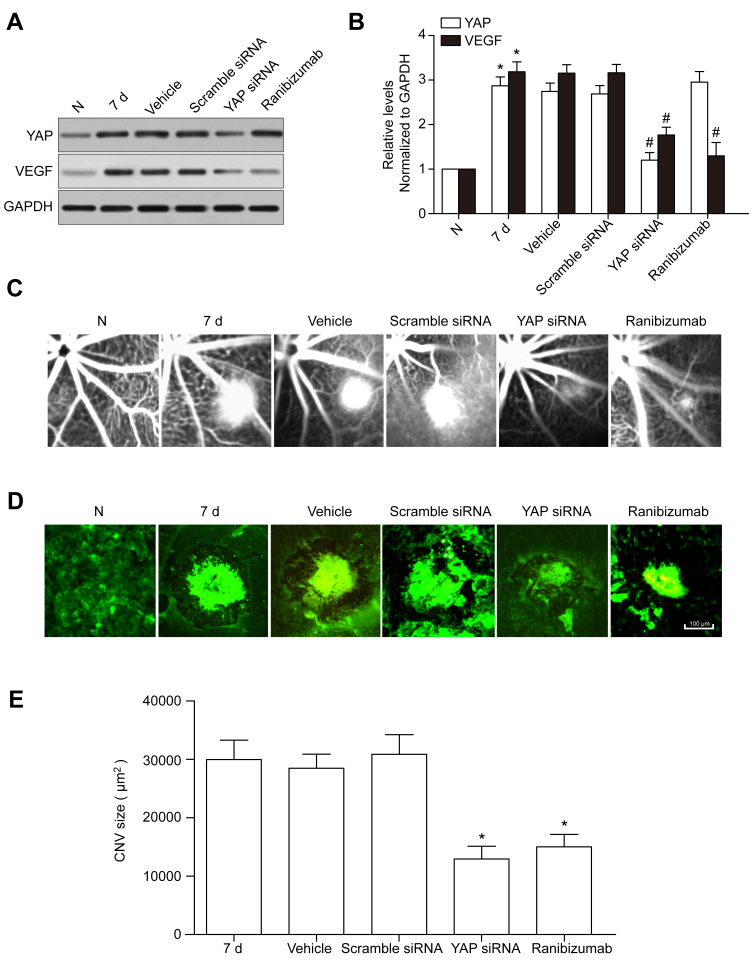

To further investigate the functions of YAP in CNV, intraperitoneal (IP) injection of YAP siRNA was applied in the mouse CNV model, and ZBR was used as a positive control. Three types of YAP siRNA (mm-Yap-si-1, -2, and -3, shown in Table 1) and scramble siRNA were used for IP injection, with mm-Yap-si-2 showing the highest knockdown efficiency, which was used in the subsequent experiments (data not shown). Then, the YAP and VEGF expression levels following the YAP siRNA IP injection and laser injury were measured, showing that the YAP protein levels in the RPE-choroid complexes and the retina were reduced dramatically in the YAP siRNA and RBZ groups compared with those in the control, vehicle, and scramble siRNA groups. Furthermore, VEGF expression showed a decrease similar to that of YAP (Figure 2A,B), suggesting that YAP may promote CNV formation by upregulating VEGF expression.

Table 1. The siRNAs used in the study.

| SiRNA name | Sequence (5′-3′) | position |

|---|---|---|

| Scramble siRNA |

Sense: UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUdTdT |

None |

| Anti-sense: ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAAdTdT | ||

| mm-Yap-si-1 |

Sense: GGAGAAGUUUACUACAUAAdTdT |

891 |

| Anti-sense: UUAUGUAGUAAACUUCUCCdTdT | ||

| mm-Yap-si-2 |

Sense: CAAGACAUCUUCUGGUCAAdTdT |

701 |

| Anti-sense: UUGACCAGAAGAUGUCUUGdTdT | ||

| mm-Yap-si-3 | Sense: GAAUUGAGAACAAUGACAAdTdT |

1278 |

| Anti-sense: UUGUCAUUGUUCUCAAUUCdTdT |

Figure 2.

YAP siRNA IP injection reduces VEGF expression and the leakage area of CNV. A: YAP and VEGF protein levels after scramble siRNA and YAP siRNA intraperitoneal (IP) injection and intravitreal ranibizumab injection (IVR) were detected with western blotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. B: The histogram shows the densitometric analysis of the average levels of YAP and VEGF relative to GAPDH. *p<0.05; compared to the 7 day post-laser photocoagulation group. C: Hyper-fluorescence surrounding the laser spots reflects relatively weak leakage (grade 1) in the YAP siRNA IP injected mouse retinas. D: Mouse RPE-choroid flat mount preparations from laser-injured regions were fluorescently labeled with the endothelial and microglial cell marker isolectin-B4 (63X magnification). Scale bars = 100 μm. E: Comparison of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) size in the 7 day post-laser photocoagulation, vehicle, scramble siRNA, YAP siRNA, and RBZ groups. *p<0.05, compared to the 7 day post-laser photocoagulation group.

The fluorescein angiogram assays showed that the leakage area of CNV decreased in the YAP siRNA and RBZ groups 7 days after laser exposure (Figure 2C). A well-defined radial array of isolectin-labeled vessels was visible within the CNV area in the 7 day, vehicle, and scramble siRNA groups (Figure 2D). Compared to the 7 day, vehicle, and scramble siRNA groups, the extent of CNV was smaller in the YAP siRNA and RBZ groups (Figure 2E).

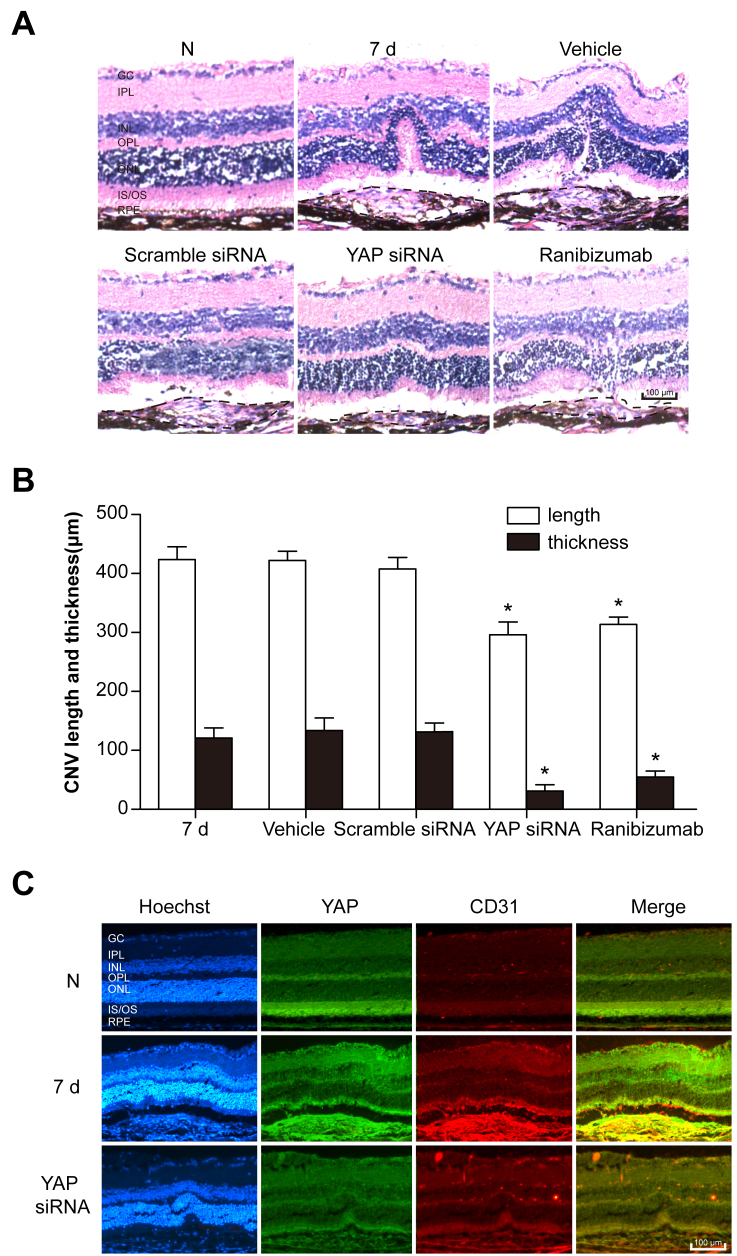

YAP is localized in the vascular endothelium within the CNV site

Seven days after laser exposure, histopathology analysis showed that YAP siRNA IP injection and IVR statistically significantly decreased the thickness and length of the retinal lesions caused by CNV (Figure 3A,B). To identify the cellular localization of YAP within the CNV site, double immunostaining of YAP with CD31, a marker for endothelial cells, was performed. Within the CNV site, YAP was localized in the vascular endothelium (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

YAP is localized in endothelial cells. A: Normal mouse retinal and choroid structure. Each photograph shows the central area of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) within the mouse retinas and choroids in the 7 day post-laser photocoagulation, vehicle, scramble siRNA, YAP siRNA, or ranibizumab (RBZ) group. Scale bar: 100 μm (RPE: retinal pigment epithelium; OS: outer segment; IS: inner segment; ONL: outer nuclear layer; OPL: outer plexiform layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; IPL: inner plexiform layer; GC: ganglion cell layer). B: Statistical analysis of the data of the 7 day post-laser photocoagulation, vehicle, scramble siRNA, YAP siRNA, and RBZ groups. n = 12–16 spots. *p<0.05, compared to the 7 day post-laser photocoagulation group. Black dashed lines represent the edge of CNV. C: Cellular localization of YAP in the retina/choroid cryosections was determined with double immunostaining with endothelial marker CD31. Scale bar = 100 μm.

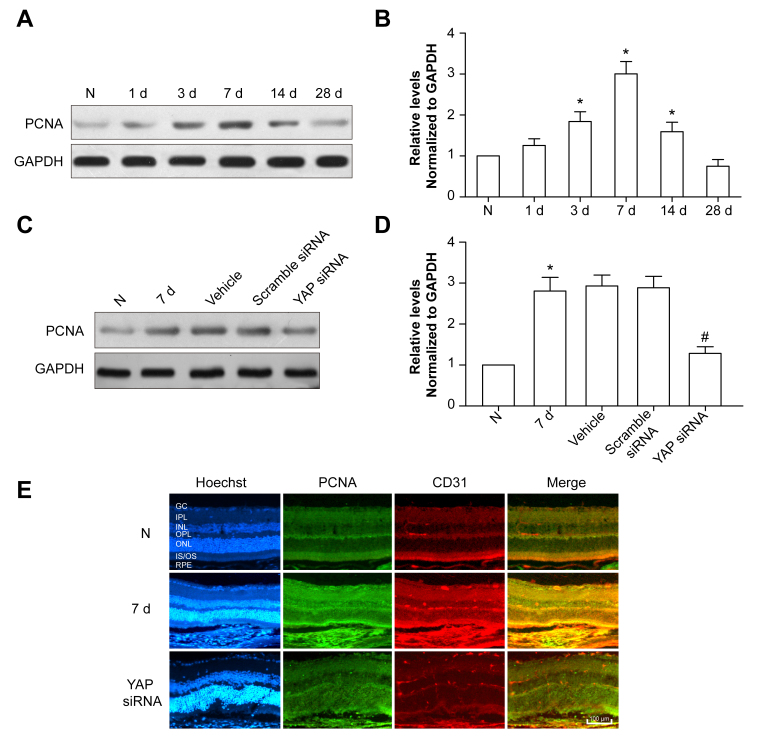

YAP siRNA inhibits the proliferation of endothelial cells

Previous studies have revealed that YAP promotes the proliferation of corneal endothelial cells [26] and vascular smooth muscle cells [27]. Therefore, PCNA expression was detected in the mouse CNV model, showing that the PCNA protein level increased following laser exposure, which peaked at 7 days (Figure 4A,B). After YAP siRNA IP injection, PCNA expression decreased compared to that in the 7 day group (Figure 4C,D), which was consistent with the immunofluorescence results (Figure 4E). Taken together, these data indicate that YAP siRNA facilitates CNV by inhibiting the proliferation of endothelial cells.

Figure 4.

YAP siRNA inhibits the proliferation of endothelial cells. A: The PCNA protein level was detected with western blotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. B: The Bar Chart showed the ratio of PCNA to GAPDH. *p<0.05, compared to the normal control group. C: The PCNA protein level following scramble siRNA or YAP siRNA intravitreal (IP) injection was detected with western blotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. D: The Bar Chart showed the ratio of PCNA to GAPDH. *p<0.05, compared to the 7 day post-laser photocoagulation group. E: Double immunostaining of PCNA and CD31 in the normal control, 7 day post-laser photocoagulation, and YAP siRNA groups. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Discussion

The mouse laser-induced CNV model is widely used in nAMD research. Developed originally for primates [28], this model was later adapted for rodents [29]. These animal models are highly applicable to CNV that occasionally occurs in human eyes after accidental laser burns [30]. Laser-induced CNV models provide preclinical evidence to support the clinical evaluation of anti-VEGF drugs for ocular neovascular diseases such as AMD and diabetic retinopathy [31]. In this study, the mouse laser-induced CNV model was generated and revealed that the VEGF protein level peaked at 7 days, which is consistent with previous research [32-34]. Polyethylene glycol-8 (PEG-8) subretinal injection can also induce CNV based on the principles of intraocular complement activation in mice, with VEGF peaking 5 days after PEG-8 exposure [35]. A JR5558 mouse with an rd8 mutation on a C57BL/6J background is an established model of spontaneous CNV, with spontaneous CNV starting between postnatal days 10 and 15 and increasing in extent and severity, subsequently causing RPE disruption and dysfunction [36,37]. Considering the cost and the lack of relationship between CNV and gene mutation, we did not use mutated mice.

The process of CNV formation involves multiple angiogenic factors, including VEGF, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factors, tumor necrosis factor, pigment epithelium-derived growth factor, interleukins, the complement system, chemokines, ephrins, and angiopoietins [38]. Among them, VEGF plays a central role in CNV. Therefore, intravitreal anti-VEGF agents are the mainstay of nAMD treatment worldwide. Intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy, including ranibizumab, does not cure the disease, but it decreases the rate of progression and facilitates visual improvements in some patients [39]. In this study, ranibizumab also inhibited VEGF expression and promoted CNV formation.

YAP promotes tissue growth and cell viability by regulating the activity of multiple transcription factors, including TEA domain family (TEADs) and Sma- and Mad-related family (SMADs) members [16,40]. YAP/TEAD activates CD44 transcription by binding to the CD44 promoter at TEAD binding sites. However, CD44 regulates NF2 (an upstream molecule of YAP) phosphorylation according to cell density and sequentially promotes the YAP transcriptional coactivator, suggesting that CD44 has two pivotal functional roles as an upstream suppressor of the Hippo pathway and as a downstream target regulated by YAP/TEAD [41]. CD44 is a cell–surface adhesion molecule and a receptor for hyaluronan (HA), a major component of the extracellular matrix, which is involved in cell adhesion [42], proliferation [43], inflammation [44,45], tumor invasion, and metastasis [46]. In addition to the proliferation of endothelial cells, inflammation is another pathogenic factor in CNV [47-49]. CD44 is maximally induced at 3–5 days post-laser photocoagulation in rats and is localized to the RPE, choroidal vascular endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells, suggesting that CD44 expression before new vessel formation may be linked to the initiation of CNV [50,51]. Moreover, antibody-based blockade of CD44 significantly reduced CNV [51]. Whether YAP promotes the proliferation and inflammatory response of endothelial cells via CD44 will be addressed in a future study.

A recent study revealed that transglutaminase 2 (TG2; Gene ID 7052; OMIM 190196) is a direct target gene of the YAP/TAZ response, which is supported by YAP1 and TAZ interactions with the TG2 promoter to regulate TG2 mRNA and protein levels in MCF10A, HaCaT, and HCT116 cells [52]. TG2, also known as tissue transglutaminase, has multiple functions in protein cross-linking and protein kinases [53] and serves as a scaffolding factor [54]. TG2 activity has been implicated in various physiologic activities, including apoptosis [55], angiogenesis [56], wound healing [57], and cellular differentiation [58]. TG2 in ECs acts as a multifunctional protein during angiogenesis by regulating the deposition of VEGF into the extracellular matrix (ECM) and facilitating the activation of its signaling through VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2). Based on previous research, the hypothesis that YAP may regulate CNV through TG2 functions warrants further study.

The Hippo signaling cascade is regulated by various upstream factors, including cell–cell contact, organ size sensing machinery, and other signaling pathways regulated by WNT, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), and several G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), especially Gα12/13-linked GPCRs [59]. Moreover, a recent study [60] showed that YAP is essential for tissue morphogenesis mediated through a Rho GTPase-activating protein, ARHGAP18, in the regulation of the cortical actomyosin network and filopodia formation in medaka and zebrafish. TGF-β is a molecule with pleiotropic effects that participates in cell proliferation and differentiation during angiogenesis and fibrotic processes, and the presence of TGF-β in neovascular membranes has been demonstrated [61,62]. TGF-β families are expressed in CNV [63]. Several studies have found that TGF-β significantly enhances VEGF secretion, vascular permeability, and extracellular matrix remodeling on its own or in concert with other cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [64,65]. Therefore, we proposed that YAP expression may be upregulated by TGF-β during CNV formation, which requires further investigation.

In summary, this study demonstrated that the upregulation of YAP promoted CNV formation by upregulating the proliferation of endothelial cells. Treatment with YAP siRNA significantly decreased the extent of laser-induced CNV in a mouse model, suggesting that YAP may be an important molecular target for antiangiogenesis therapies in AMD. There are limitations in this study that should be mentioned. First, the detailed mechanism of YAP in promoting endothelial cell proliferation has not been investigated. Second, whether YAP promotes CNV formation through other pathways, such as regulation of the inflammatory response, remains uncertain.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81470616).

References

- 1.Bogunovic H, Waldstein SM, Schlegl T, Langs G, Sadeghipour A, Liu X, Gerendas BS, Osborne A, Schmidt-Erfurth U. Prediction of Anti-VEGF Treatment Requirements in Neovascular AMD Using a Machine Learning Approach. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:3240–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki T, Hirakawa S, Shimauchi T, Ito T, Sakabe J, Detmar M, Tokura Y. VEGF-A promotes IL-17A-producing gammadelta T cell accumulation in mouse skin and serves as a chemotactic factor for plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurtagic E, Rich CB, Buczek-Thomas JA, Nugent MA. Neutrophil Elastase-Generated Fragment of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Stimulates Macrophage and Endothelial Progenitor Cell Migration. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashina K, Tsubosaka Y, Kobayashi K, Omori K, Murata T. VEGF-induced blood flow increase causes vascular hyper-permeability in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;464:590–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yazdi MH, Faramarzi MA, Nikfar S, Falavarjani KG, Abdollahi M. Ranibizumab and aflibercept for the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1349–58. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1057565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medina FMC, Motta A, Takahashi WY, Carricondo PC, Motta M, Melo MB, Vasconcellos JPC. Association of the CFH Y402H Polymorphism with the 1-Year Response of Exudative AMD to Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Treatment in the Brazilian Population. Ophthalmic Res. 2017 doi: 10.1159/000475995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown GC, Brown MM, Lieske HB, Turpcu A, Rajput Y. The comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab for neovascular macular degeneration revisited. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2017;3:5. doi: 10.1186/s40942-016-0058-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart MW. A Review of Ranibizumab for the Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy. Ophthalmol Ther. 2017;6:33–47. doi: 10.1007/s40123-017-0083-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ntumba K, Akla N, Oh SP, Eichmann A, Larrivee B. BMP9/ALK1 inhibits neovascularization in mouse models of age-related macular degeneration. Oncotarget. 2016;7:55957–69. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, Han X, Kunz E, Hartnett ME. Thy-1 Regulates VEGF-Mediated Choroidal Endothelial Cell Activation and Migration: Implications in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:5525–34. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Y, Shin DJ, Pan H, Lin Z, Dreyfuss JM, Camargo FD, Miao J, Biddinger SB. YAP suppresses gluconeogenic gene expression via PGC1alpha. Hepatology. 2017 doi: 10.1002/hep.29373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plouffe SW, Hong AW, Guan KL. Disease implications of the Hippo/YAP pathway. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:212–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halder G, Johnson RL. Hippo signaling: growth control and beyond. Development. 2011;138:9–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.045500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu FX, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes Dev. 2013;27:355–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.210773.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staley BK, Irvine KD. Hippo signaling in Drosophila: recent advances and insights. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:3–15. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos A, Camargo FD. The Hippo signaling pathway and stem cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:339–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang N, Bai H, David KK, Dong J, Zheng Y, Cai J, Giovannini M, Liu P, Anders RA, Pan D. The Merlin/NF2 tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate tissue homeostasis in mammals. Dev Cell. 2010;19:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagi H, Asanoma K, Ohgami T, Ichinoe A, Sonoda K, Kato K. GEP oncogene promotes cell proliferation through YAP activation in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:4471–80. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Shi S, Guo Z, Zhang X, Han S, Yang A, Wen W, Zhu Q. Overexpression of YAP and TAZ is an independent predictor of prognosis in colorectal cancer and related to the proliferation and metastasis of colon cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21.Dong Q, Fu L, Zhao Y, Du Y, Li Q, Qiu X, Wang E. Rab11a promotes proliferation and invasion through regulation of YAP in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:27800–11. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng H, Ortiz A, Shen PF, Cheng CJ, Lee YC, Yu G, Lin SC, Creighton CJ, Yu-Lee LY, Lin SH. Angiomotin regulates prostate cancer cell proliferation by signaling through the Hippo-YAP pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8:10145–60. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu FX, Zhao B, Guan KL. Hippo Pathway in Organ Size Control, Tissue Homeostasis, and Cancer. Cell. 2015;163:811–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim J, Kim YH, Park DY, Bae H, Lee DH, Kim KH, Hong SP, Jang SP, Kubota Y, Kwon YG, Lim DS, Koh GY. YAP/TAZ regulates sprouting angiogenesis and vascular barrier maturation. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3441–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI93825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nourinia R, Rezaei Kanavi M, Kaharkaboudi A, Taghavi SI, Aldavood SJ, Darjatmoko SR, Wang S, Gurel Z, Lavine JA, Safi S, Ahmadieh H, Daftarian N, Sheibani N. Ocular Safety of Intravitreal Propranolol and Its Efficacy in Attenuation of Choroidal Neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:8228–35. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsueh YJ, Chen HC, Wu SE, Wang TK, Chen JK, Ma DH. Lysophosphatidic acid induces YAP-promoted proliferation of human corneal endothelial cells via PI3K and ROCK pathways. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2015;2:15014. doi: 10.1038/mtm.2015.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng X, Liu P, Zhou X, Li MT, Li FL, Wang Z, Meng Z, Sun YP, Yu Y, Xiong Y, Yuan HX, Guan KL. Thromboxane A2 Activates YAP/TAZ Protein to Induce Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Migration. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:18947–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.739722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan SJ. The development of an experimental model of subretinal neovascularization in disciform macular degeneration. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1979;77:707–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert V, Lecomte J, Hansen S, Blacher S, Gonzalez ML, Struman I, Sounni NE, Rozet E, de Tullio P, Foidart JM, Rakic JM, Noel A. Laser-induced choroidal neovascularization model to study age-related macular degeneration in mice. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2197–211. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nehemy M, Torqueti-Costa L, Magalhaes EP, Vasconcelos-Santos DV, Vasconcelos AJ. Choroidal neovascularization after accidental macular damage by laser. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2005;33:298–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma J, Sun Y, Lopez FJ, Adamson P, Kurali E, Lashkari K. Blockage of PI3K/mTOR Pathways Inhibits Laser-Induced Choroidal Neovascularization and Improves Outcomes Relative to VEGF-A Suppression Alone. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:3138–44. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L, Lee AY, Wigg JP, Peshavariya H, Liu P, Zhang H. miR-126 Regulation of Angiogenesis in Age-Related Macular Degeneration in CNV Mouse Model. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17060895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rohrer B, Coughlin B, Bandyopadhyay M, Holers VM. Systemic human CR2-targeted complement alternative pathway inhibitor ameliorates mouse laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2012;28:402–9. doi: 10.1089/jop.2011.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyzogubov V, Wu X, Jha P, Tytarenko R, Triebwasser M, Kolar G, Bertram P, Bora PS, Atkinson JP, Bora NS. Complement regulatory protein CD46 protects against choroidal neovascularization in mice. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:2537–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyzogubov VV, Tytarenko RG, Liu J, Bora NS, Bora PS. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-induced mouse model of choroidal neovascularization. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16229–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.204701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paneghetti L, Ng YS. A novel endothelial-derived anti-inflammatory activity significantly inhibits spontaneous choroidal neovascularisation in a mouse model. Vasc Cell. 2016;8:2. doi: 10.1186/s13221-016-0036-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagai N, Lundh von Leithner P, Izumi-Nagai K, Hosking B, Chang B, Hurd R, Adamson P, Adamis AP, Foxton RH, Ng YS, Shima DT. Spontaneous CNV in a novel mutant mouse is associated with early VEGF-A-driven angiogenesis and late-stage focal edema, neural cell loss, and dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:3709–19. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert NG, ElShelmani H, Singh MK, Mansergh FC, Wride MA, Padilla M, Keegan D, Hogg RE, Ambati BK. Risk factors and biomarkers of age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;54:64–102. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li S, Hu A, Wang W, Ding X, Lu L. Combinatorial treatment with topical NSAIDs and anti-VEGF for age-related macular degeneration, a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bae JS, Kim SM, Lee H. The Hippo signaling pathway provides novel anti-cancer drug targets. Oncotarget. 2017;8:16084–98. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka K, Osada H, Murakami-Tonami Y, Horio Y, Hida T, Sekido Y. Statin suppresses Hippo pathway-inactivated malignant mesothelioma cells and blocks the YAP/CD44 growth stimulatory axis. Cancer Lett. 2017;385:215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Yu C, Wu Y, Sun X, Su Q, You C, Xin H.CD44+ fibroblasts increases breast cancer cell survival and drug resistance via IGF2BP3–CD44–IGF2 signalling. J Cell Mol Med 2017. 21:1979-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, Qian L, Lin J, Huang G, Hao N, Wei X, Wang W, Liang J.CD44 regulates prostate cancer proliferation, invasion and migration via PDK1 and PFKFB4. Oncotarget 2017. 8:65143-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuwahara G, Hashimoto T, Tsuneki M, Yamamoto K, Assi R, Foster TR, Hanisch JJ, Bai H, Hu H, Protack CD, Hall MR, Schardt JS, Jay SM, Madri JA, Kodama S, Dardik A. CD44 Promotes Inflammation and Extracellular Matrix Production During Arteriovenous Fistula Maturation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:1147–56. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kosovrasti VY, Nechev LV, Amiji MM. Peritoneal Macrophage-Specific TNF-alpha Gene Silencing in LPS-Induced Acute Inflammation Model Using CD44 Targeting Hyaluronic Acid Nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2016;13:3404–16. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xue J, Zhu Y, Sun Z, Ji R, Zhang X, Xu W, Yuan X, Zhang B, Yan Y, Yin L, Xu H, Zhang L, Zhu W, Qian H. Tumorigenic hybrids between mesenchymal stem cells and gastric cancer cells enhanced cancer proliferation, migration and stemness. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:793. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1780-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwanishi H, Fujita N, Tomoyose K, Okada Y, Yamanaka O, Flanders KC, Saika S. Inhibition of development of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization with suppression of infiltration of macrophages in Smad3-null mice. Lab Invest. 2016;96:641–51. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2016.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weber ML, Heier JS. Choroidal Neovascularization Secondary to Myopia, Infection and Inflammation. Dev Ophthalmol. 2016;55:167–75. doi: 10.1159/000431194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim SJ, Lee HJ, Yun JH, Ko JH, Choi DY, Oh JY. Intravitreal TSG-6 suppresses laser-induced choroidal neovascularization by inhibiting CCR2+ monocyte recruitment. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11872. doi: 10.1038/srep11872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen WY, Yu MJ, Barry CJ, Constable IJ, Rakoczy PE. Expression of cell adhesion molecules and vascular endothelial growth factor in experimental choroidal neovascularisation in the rat. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1063–71. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.9.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mochimaru H, Takahashi E, Tsukamoto N, Miyazaki J, Yaguchi T, Koto T, Kurihara T, Noda K, Ozawa Y, Ishimoto T, Kawakami Y, Tanihara H, Saya H, Ishida S, Tsubota K. Involvement of hyaluronan and its receptor CD44 with choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4410–5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu CY, Pobbati AV, Huang Z, Cui L, Hong W. Transglutaminase 2 Is a Direct Target Gene of YAP/TAZ-Letter. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4734–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mishra S, Saleh A, Espino PS, Davie JR, Murphy LJ. Phosphorylation of histones by tissue transglutaminase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5532–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akimov SS, Krylov D, Fleischman LF, Belkin AM. Tissue transglutaminase is an integrin-binding adhesion coreceptor for fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:825–38. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nemes Z, Jr, Adany R, Balazs M, Boross P, Fesus L. Identification of cytoplasmic actin as an abundant glutaminyl substrate for tissue transglutaminase in HL-60 and U937 cells undergoing apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20577–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones RA, Kotsakis P, Johnson TS, Chau DY, Ali S, Melino G, Griffin M. Matrix changes induced by transglutaminase 2 lead to inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1442–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haroon ZA, Hettasch JM, Lai TS, Dewhirst MW, Greenberg CS. Tissue transglutaminase is expressed, active, and directly involved in rat dermal wound healing and angiogenesis. FASEB J. 1999;13:1787–95. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.13.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matic I, Sacchi A, Rinaldi A, Melino G, Khosla C, Falasca L, Piacentini M. Characterization of transglutaminase type II role in dendritic cell differentiation and function. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:181–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1009691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu FX, Zhao B, Panupinthu N, Jewell JL, Lian I, Wang LH, Zhao J, Yuan H, Tumaneng K, Li H, Fu XD, Mills GB, Guan KL. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. 2012;150:780–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Porazinski S, Wang H, Asaoka Y, Behrndt M, Miyamoto T, Morita H, Hata S, Sasaki T, Krens SFG, Osada Y, Asaka S, Momoi A, Linton S, Miesfeld JB, Link BA, Senga T, Shimizu N, Nagase H, Matsuura S, Bagby S, Kondoh H, Nishina H, Heisenberg CP, Furutani-Seiki M. YAP is essential for tissue tension to ensure vertebrate 3D body shape. Nature. 2015;521:217–21. doi: 10.1038/nature14215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Meeteren LA, Goumans MJ, ten Dijke P. TGF-beta receptor signaling pathways in angiogenesis; emerging targets for anti-angiogenesis therapy. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:2108–20. doi: 10.2174/138920111798808338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tosi GM, Caldi E, Neri G, Nuti E, Marigliani D, Baiocchi S, Traversi C, Cevenini G, Tarantello A, Fusco F, Nardi F, Orlandini M, Galvagni F. HTRA1 and TGF-beta1 Concentrations in the Aqueous Humor of Patients With Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:162–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-20922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schlingemann RO. Role of growth factors and the wound healing response in age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:91–101. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suzuki Y, Ito Y, Mizuno M, Kinashi H, Sawai A, Noda Y, Mizuno T, Shimizu H, Fujita Y, Matsui K, Maruyama S, Imai E, Matsuo S, Takei Y. Transforming growth factor-beta induces vascular endothelial growth factor-C expression leading to lymphangiogenesis in rat unilateral ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int. 2012;81:865–79. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walshe TE, Saint-Geniez M, Maharaj AS, Sekiyama E, Maldonado AE, D’Amore PA. TGF-beta is required for vascular barrier function, endothelial survival and homeostasis of the adult microvasculature. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]