Abstract

This longitudinal study examined pragmatic language in boys and girls with Down syndrome (DS) at up to three time points, using parent report, standardized and direct assessments. We also explored relationships among theory of mind, executive function, nonverbal mental age, receptive and expressive vocabulary, grammatical complexity, and pragmatic competence. Controlling for cognitive and language abilities, children with DS demonstrated greater difficulty than younger typically developing controls on parent report and standardized assessments, but only girls with DS differed on direct assessments. Further, pragmatic skills of individuals with DS developed at a delayed rate relative to controls. Some sex-specific patterns of pragmatic impairments emerged. Theory of mind and executive function both correlated with pragmatic competence. Clinical and theoretical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Down syndrome, pragmatic language, development

Pragmatic language encompasses a broad range of skills, including conversational turn-taking, topic maintenance, and repair of communicative breakdowns, along with nonverbal communication (e.g., body language, gestures) and paralinguistic variations in rate, intonation, and rhythm (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2015; Grice, 1975; Nelson, 1978; Timler, Olswang, & Coggins, 2005). These abilities develop and change into adulthood (e.g., Berman & Slobin, 1994), and in typical development there is a dramatic increase in social demands with age (Gleason & Ratner, 2012). Pragmatic language development also draws on a range of abilities, including general cognitive ability, executive function, receptive and expressive vocabulary, grammatical complexity, and theory of mind (Bruner, 1990; Fabbretti, Pizzuto, Vicari, & Volterra, 1997; Gooch, Thompson, Nash, Snowling, & Hulme, 2016; Gopnik, Meltzoff, & Kuhl, 1999; Laws & Bishop, 2004). Therefore, assessing pragmatic development is especially relevant for clinical populations, who often present with deficits in these related abilities.

Down syndrome (DS) occurs in approximately 1/700 live births (Parker et al., 2010) and is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability, with cognitive abilities in the moderately impaired range (i.e., IQ 35–50) for approximately 80% of individuals (Pueschel, 1995; Roizen, 2007). Structural language deficits are also prominent in DS, including deficits in both receptive and expressive vocabulary relative to mental age matched controls and particular difficulties with comprehension and production of complex syntax beyond what would be expected for nonverbal cognitive abilities (see Martin, G. E., Klusek, Estigarribia, & Roberts, 2009, for review). Despite such difficulties, individuals with DS are often known for their engaging and social nature (Moore, Oates, Hobson, & Goodwin, 2002; Wishart & Johnston, 1990). This leads to a complex pragmatic profile, such that there is a discrepancy between social motivation and language competence.

Prior work has noted several relative strengths in the pragmatic language profile of DS, and individuals with DS appear to exhibit fewer pragmatic language violations relative to other developmental disorders characterized by pragmatic impairment [e.g., autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and fragile X syndrome (FXS) with comorbid ASD (Abbeduto & Chapman, 2005; Klusek, Losh, & Martin, 2014; Martin, G. E., Losh, Estigarribia, Sideris, & Roberts, 2013; Roberts et al., 2007)]. Compared to younger typically developing (TD) controls, similar rates of parent-reported social relationships and attempts to repair conversational breakdown have been observed (Laws & Bishop, 2004; Johnston & Stanfield, 1997). Several studies have also suggested that individuals with DS demonstrate relatively intact nonverbal communicative strategies (John & Mervis, 2010; Porto-Cunha & Limongi, 2008; Soares, de Britto Pereira, & Sampaio, 2009), especially to remedy conversational breakdown (Abbeduto et al., 2008).

Despite these strengths, pragmatic impairments have also been observed in DS. Individuals with DS have been shown to elaborate less, introduce fewer new topics in conversation, and to use less sophisticated topic maintenance strategies (Roberts et al., 2007; Tannock, 1988). Difficulty conveying communicative intent relative to mental age-matched controls has also been observed (Abbeduto et al., 2008). Further, individuals with DS have been reported to demonstrate increased use of stereotyped language as compared to TD controls of a similar mental age (Laws & Bishop, 2004), though at lower rates than observed in other developmental disabilities, such as FXS or ASD (Abbeduto, Brady, & Kover, 2007; Martin, G. E., Roberts, Helm-Estabrooks, Sideris, & Assal, 2012; Roberts et al., 2007). Of note, studies of pragmatic abilities in DS have historically only included boys or combined sexes without examining sex differences, despite well-documented sex differences in pragmatic abilities in typical development (Berghout, Salehi, & Leffler, 1987; Cook, Fritz, McCornack, & Visperas, 1985; Kothari, Skuse, Wakefield, & Micali, 2013; Leaper, 1991; Sigleman & Holtz, 2013). As such, and because DS is not caused by mutations in the sex chromosomes, findings in boys with DS have often been generalized to girls (Finestack, Palmer, & Abbeduto, 2012; Keller-Bell & Abbeduto, 2007). However, Berglund, Eriksson, and Johansson (2001) found that girls with DS demonstrated better pragmatic abilities on parent-reported measures in a sample of children ages 1–5 years, warranting further investigation of sex differences in pragmatics in DS.

Few studies have investigated pragmatic language in individuals with DS longitudinally, particularly in the context of examining sex differences. Tager-Flusberg and Anderson (1991) examined spontaneous language over a one-year period in boys with ASD and DS, and found that, in contrast to children with ASD, the DS group showed growth in both syntactic and pragmatic skills, and that these abilities were highly related. That is, as children became more proficient syntactically, they applied these language skills to make more novel contributions to ongoing conversation. In contrast, comparing pragmatic growth of children with DS to mental-age matched TD controls on a standardized measure of pragmatic language that involves making pragmatic language judgments (the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language-Pragmatic Judgment Subscale), G. E. Martin et al. (2013) reported that boys with DS demonstrated greater difficulties on vocabulary, syntax, and pragmatic language and developed these skills at a slower rate than TD boys of similar nonverbal mental age. There are mixed findings overall regarding changes in rates of development of other abilities across age periods in DS, with some studies suggesting “plateaus” in development and other suggesting no differences in rates of development between preschool and adult years (Cuskelly, Povey, & Jobling, 2016; Dykens et al., 2006; de Graaf & de Graaf, 2016). This suggests a continued need for research on longitudinal development of pragmatic language in DS, examining different types of pragmatic skills with a particular focus on comparison groups and assessment methods employed.

Other cognitive domains that may contribute to pragmatic language in DS are also critical to examine. Not surprisingly, evidence suggests that pragmatic abilities observed in individuals with DS are limited largely by cognitive and structural language deficits (Fabbretti et al., 1997; Laws & Bishop, 2004). However, individuals with DS also demonstrate deficits in theory of mind (see Cebula, Moore, & Wishart, 2010, for review) and executive function (Lanfranchi, Jerman, Dal Pont, Alberti, & Vianello, 2010), skills that are known to relate to pragmatic language in typical development (Bruner, 1990; Gooch et al., 2016; Gopnik et al., 1999). Theory of mind, or the ability to infer thoughts, emotions, and intentions in others is a critical skill for successful communication, and pragmatic language in particular (Fiske & Taylor, 1991), and has been previously found to relate to pragmatic competence in boys with DS (Losh, Martin, Klusek, Hogan-Brown, & Sideris, 2012). Executive function (e.g., working memory, task switching, planning) is another critical set of cognitive skills supporting pragmatic competence in typical development (Blain-Brière, Bouchard, & Bigras, 2014), which has not been examined in relationship to pragmatic language in DS.

This study attempted to characterize pragmatic language and related language, cognitive, and theory of mind skills that may contribute to impairments in pragmatic language in boys and girls with DS. Specifically, we aimed to do the following:

Characterize profiles of pragmatic language abilities in boys and girls with DS at a single time point using parent-report, standardized assessment, and direct assessments of pragmatic language during semi-structured conversational interactions. We hypothesized that both boys and girls with DS would show greater pragmatic impairments relative to TD controls across all measurement types and different pragmatic skills assessed. Further, in light of prior findings suggesting that girls with DS demonstrate less impairment than boys with DS (Berglund et al., 2001), we hypothesized that girls with DS in the current sample would demonstrate stronger pragmatic abilities than boys with DS. However, we hypothesized that girls with DS would demonstrate greater impairment relative to TD girls, given that TD girls demonstrate advantages in pragmatics in typical development.

Examine developmental trajectories of pragmatic language development in individuals with DS. We hypothesized that individuals with DS would demonstrate a delay in pragmatic development relative to controls, across different types of pragmatic abilities, and, consistent with our first hypothesis, that girls may show faster rates of development than boys with DS.

Explore correlates of pragmatic language in DS. Given prior evidence that language, cognition, and theory of mind may importantly relate to pragmatic language across different developmental disorders, we explored these variables in relationship to pragmatic abilities across measures. Given the exploratory nature of this aim we did not generate a-priori hypotheses.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

At Visit 1, participants included 22 school-age boys and 24 school-age girls with DS and control groups of 23 younger boys and 24 younger girls with typical development (TD) of similar mental age. Participants were drawn from a larger longitudinal study of pragmatic language development in neurodevelopmental disorders in which assessments were completed at up to three annual visits. Because enrollment for this study was ongoing, not all participants were able to complete three visits prior to the conclusion of funding, and thus in the current study sample sizes decrease with each visit across groups. Table 1 summarizes the number of participants completing assessments at each visit. No significant differences were found for measures of nonverbal mental age and expressive/receptive vocabulary between participants who completed one visit and participants who completed more than one visit.

Table 1.

Sample size of assessments administered at each visit

| Groups | Leiter | Expressive Vocabulary Test |

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test |

Mean Length of Utterance |

Children’s Communication Checklist, Second Edition |

Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language |

Pragmatic Rating Scale- School Age |

Theory of Mind |

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function Preschool Version |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | DS Boys | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 14 | 22 | 20 | 22 | 13 |

| DS Girls | 24 | 24 | 24 | 23 | 20 | 24 | 15 | 22 | 22 | |

| TD Boys | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 15 | 23 | 18 | 21 | 19 | |

| TD Girls | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 13 | 24 | 19 | 17 | 21 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Visit 2 | DS Boys | 20 | -- | 20 | 18 | 13 | 20 | -- | 19 | -- |

| DS Girls | 22 | -- | 22 | 21 | 15 | 22 | -- | 22 | -- | |

| TD Boys | 19 | -- | 19 | 15 | 8 | 18 | -- | 15 | -- | |

| TD Girls | 15 | -- | 15 | 14 | 14 | 15 | -- | 10 | -- | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Visit 3 | DS Boys | 15 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 8 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 9 |

| DS Girls | 14 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 9 | |

| TD Boys | 11 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 11 | -- | 6 | 6 | |

| TD Girls | 11 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 11 | -- | 3 | 8 | |

Note. DS = Down syndrome; TD = typically developing.

Table 2 summarizes participant characteristics at each visit. Boys with DS had a mean age of 10.93 and girls with DS a mean age of 8.99 years, with mean mental ages of 5.33 and 4.98 years, respectively. Individuals with DS and TD were recruited with the goal of group matching on nonverbal mental age at Visit 1 and thus TD participants were significantly younger (boys mean = 4.90, girls = 5.22). However, pairwise comparisons demonstrated that girls with DS had a significantly lower mental age, receptive and expressive vocabulary age equivalence than boys and girls with TD at Visit 1. Greater differences emerged between individuals with DS and TD at later visits because the TD group developed these skills more rapidly than individuals with DS, and thus statistical analyses accounted for these differences, as described in the Analysis Plan.

Table 2.

Group characteristics at each time point

| Time 1

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Mental Age1 M (SD) Range |

EVT AE2 M (SD) Range |

PPVT AE3 M (SD) Range |

Chronological Age M (SD) Range |

MLU4 M (SD) Range |

| DS Boys | 5.33 (.81)a | 5.33 (1.33)a,b | 5.15 (1.41) a | 10.93 (2.07)a | 3.11 (.75)a |

| 4.33–8.25 | 3.58–8.58 | 2.42–7.50 | 6.81–14.86 | 1.76–4.76 | |

| DS Girls | 4.98 (.74)b | 4.68 (1.39)a | 4.73 (1.82)b | 8.99 (2.15)b | 3.27 (.96)a |

| 3.83–6.83 | 1.92–7.75 | 2.08–9.75 | 5.97–14.32 | 2.25–6.60 | |

| TD Boys | 5.46 (1.43)a | 5.94 (2.07)b | 6.26 (1.94)a | 4.90 (1.38)c | 4.76 (.71)b |

| 3.58–9.17 | 2.92–12.33 | 2.17–11.58 | 3.15–8.78 | 3.14–6.06 | |

| TD Girls | 5.93 (2.50)a | 5.93 (2.30)b | 6.15 (2.90)a | 5.22 (2.27)c | 5.17 (1.42)b |

| 3.92–14.92 | 3.17–12.17 | 2.67–16.08 | 3.11–11.77 | 3.07–7.88 | |

|

| |||||

| Time 2 | |||||

|

| |||||

| DS Boys | 5.66 (1.09)a | 5.96 (1.34)a | 12.39 (2.03)a | 3.27 (.82)a | |

| 3.08–8.25 | 3.50–8.25 | 7.93–16.09 | 1.88–4.60 | ||

| DS Girls | 5.26 (.96)a | 5.39 (1.95)a | 10.25 (2.45)b | 3.36 (.77)a | |

| 3.58–7.67 | 2.92–8.42 | 7.09–16.33 | 2.26–5.27 | ||

| TD Boys | 6.82 (1.61)b | 8.61 (3.15)b | 6.36 (1.52)c | 4.68 (.78)b | |

| 5.58–11.67 | 5.25–17.75 | 4.60–10.33 | 3.56–6.21 | ||

| TD Girls | 7.67 (2.94)b | 8.16 (3.09)b | 6.78 (2.63)c | 5.25 (1.36)b | |

| 4.75–14.92 | 4.25–16.33 | 4.05–12.88 | 3.36–7.80 | ||

|

| |||||

| Time 3 | |||||

|

| |||||

| DS Boys | 6.01 (1.28)a | 6.24 (1.28)a | 6.70 (1.67)a | 14.06 (2.44)a | 3.41 (.83)a |

| 4.58–9.58 | 3.33–8.33 | 3.83–10.92 | 9.63–17.93 | 1.91–5.08 | |

| DS Girls | 5.06 (.83)a | 4.99 (1.42)a | 5.16 (2.08)b | 10.54 (1.66)b | 3.25 (.93)a |

| 4.17–7.00 | 2.75–8.00 | 3.00–9.08 | 8.25–13.42 | 2.24–5.02 | |

| TD Boys | 8.49 (3.11)b | 8.25 (1.99)b | 8.48 (1.44)c | 7.73 (1.70)c | 5.32 (1.16)b |

| 6.00–17.08 | 6.33–13.08 | 6.67–10.42 | 6.15–11.55 | 4.17–7.22 | |

| TD Girls | 9.15 (2.80)b | 9.59 (2.61)b | 9.58 (2.32)c | 8.28 (2.20)c | 5.89 (1.27)b |

| 5.58–14.25 | 6.58–15.83 | 6.50–12.92 | 5.01–11.42 | 4.57–7.98 | |

Note. DS = Down syndrome; TD = typically developing.

Mental age was assessed with the Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised

EVT AE = Expressive Vocabulary Test Age Equivalence

PPVT AE = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test Age Equivalence

MLU = mean length of utterance in morphemes. Differing superscripts indicate significant difference at p < .05.

Participants were recruited through advertisements at genetic clinics, physicians’ offices, advocacy groups, and schools and local community advertisements. All participants were screened for regular use of three word phrases and having English as their first and primary language. Pure-tone hearing thresholds were screened at 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz with a Medical Acoustic Instrument Company (MAICO) MA 40 audiometer, and children were excluded for failing the screener at 30 dB in the better ear.

Assessments included a battery of language and cognitive measures as well as parent-completed questionnaires. Assessments administered varied based on the time of the visit, as summarized in Table 1. Assessments were completed in participants’ homes, laboratory testing space, or the child’s school, based on family preference. Due to the longitudinal nature of the study, and the inclusion of special populations, not all participants could feasibly travel to the lab for testing. All participants, including those with TD, were given the option to test in their home or another quiet, comfortable space. Strategies employed to minimize participant distraction have been outlined in previous work (Hogan-Brown et al., 2013; Losh et al., 2012; Martin, G. E., et al., 2013) and ensured the testing environment was quiet and all potential distractions were removed. This study was approved by University Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

Pragmatic language

Children’s Communication Checklist, Second Edition (CCC-2). At Visit 1, parents completed the Children’s Communication Checklist, Second Edition (CCC-2; Bishop, 2003), a 70-item scale that comprehensively assesses elements of both structural language and social communicative abilities. Scaled scores for each of the 10 subscales (Speech, Syntax, Semantics, Coherence, Initiation, Scripted Language, Context, Nonverbal Communication, Social Relations, and Interests, ranging from 1 to 19) and the General Communication Composite (GCC) standard score (ranging from 40 to 160) were calculated. Lower scores indicate poorer language and communication skills. The CCC-2 demonstrates strong internal consistency (ranging from .94–.96 across age groups; Bishop, 2006), as well as test-retest reliability greater than .85 (Bishop, 2013).

Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL). Participants completed the Pragmatic Judgment subtest of the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL) (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999), which requires children to state how they would respond to certain social situations (e.g., “How would you greet an unfamiliar adult?”). The CASL has been used extensively in populations with both typical and delayed development and has strong internal consistency (reliability ranging from .77 to .92, depending on participant age) and test-retest reliability (ranging from .66 for children ages 14–16 years to .85 for children ages 5–6 years, 11 months; Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999). Age equivalence scores were used in analyses. Although a limitation of age equivalence scores is that they are not interval level, they were chosen because they allow for inclusion of participants in cases when raw scores fall outside of the range of standard scores (i.e., floor effects) and because they represent a meaningful metric (unlike raw scores).

-

Pragmatic Rating Scale, School-Age (PRS-SA). The Pragmatic Rating Scale-School Age (PRS-SA; Landa, 2011) is a rating system designed to characterize pragmatic language abilities based on semi-naturalistic, conversational interactions in the context of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord, Rutter, DeLavore, & Risi, 2001), described below. The ADOS was not administered at Visit 2 and, thus, ratings from the PRS-SA could not be obtained at that visit. Ratings were completed for all groups at Visit 1 and at Visit 3 for boys and girls with DS. The PRS-SA includes 34 operationally defined pragmatic features rated from videotape by coders blind to participant diagnostic status at the start of coding. The items included on the PRS-SA capture several broad domains of pragmatic language, including language skills hypothesized to relate to theory of mind and executive skills such as planning and working memory. For example, appropriate length of turn, ability to clarify conversational breakdowns, and discourse management abilities such as appropriate topic initiation and elaboration, and conversational reciprocity are assessed. Also assessed are speech behaviors impacting pragmatics (e.g., overly formal or scripted speech), suprasegmental features of speech (e.g., rate, rhythm, volume, intelligibility), and nonverbal communication (e.g., gestures, eye contact, facial expression). Each item is rated on a three-point scale (0, absent, 1, mild impairment, or 2, impairment present); items are then totaled to provide an overall sum of pragmatic violations. Raters were trained to a threshold of 80% reliability, and 15% of files in each diagnostic group were randomly selected for reliability coding. Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC: 1, 2) were .87 and .86 for the overall sample and for individuals with DS, respectively, which indicates “excellent” agreement (Fleiss, Levin, & Paik, 2004; Landis & Koch, 1977).

The ADOS served as the semi-naturalistic language sample from which the PRS-SA was rated. The ADOS was chosen as the conversational sample because administration is standardized across participants and includes a range of activities designed to press for social behaviors and interactions (e.g., conversational prompts, imaginary play, taking turns narrating a story). However, in contrast to standardized measures such as the CASL, examiners have the opportunity to follow the child’s lead in conversation (Tager-Flusberg et al., 2009). Participants in this study completed either a Module 2 (for individuals with phrase speech) or a Module 3 (for individuals with more complex language).

Cognitive and structural language abilities

The Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised provided an estimate of participant nonverbal mental age (Roid & Miller, 1997). Structural language abilities included expressive vocabulary, measured by the Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT; Williams, 1997), receptive vocabulary, measured by the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 3rd or 4th editions (PPVT; Dunn & Dunn, 1997, 2007), and grammatical complexity, measured by mean length of utterance in morphemes derived from the ADOS (MLU; Brown, 1973). MLU was derived from complete and intelligible utterances transcribed using the Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT; Miller & Chapman, 2008). Language samples for MLU were transcribed from the ADOS, either a full version at Visit 1 and three or a reduced version of the ADOS at Visit 2.

Theory of mind

Participants completed one of two similar batteries to assess theory of mind based on when they were enrolled in the study. The first battery included a verbal presentation of tasks assessing a range of theory of mind abilities (e.g., Perspective Taking, Diverse Desires, False Belief; Slaughter, Peterson, & Mackintosh, 2007; Wellman & Liu, 2004). For example, in one of the tasks that assesses false belief, the examiner recited a brief story to the child about a missing object, and asks the child where the character will initially look for the misplaced object (Wellman & Liu, 2004). A second, modified battery included significantly reduced language demands by acting out scenarios instead of reading stories, and incorporated additional basic tasks assessing intentionality, desires, and metarepresentational skills that are precursors to more advanced theory of mind skills. For example, the false belief task was modified to include the examiner and a confederate acting out the misplacement of an item (as opposed to the verbal scenario; Lewis & Mitchell, 1994; Matthews, Dissanayake, & Pratt 2003). To derive a single score for theory of mind, each battery was tested in separate confirmatory factor analytic (CFA) models, resulting in a single factor score with a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of one. Additional details on the tasks, scoring procedures, and factor analysis can be found in Losh et al. (2012). These measures directly assess discrete theory of mind skills through targeted questions and prompts that are hypothesized to underlie many of the conversational skills assessed by the PRS-SA.

Executive functioning

Primary caregivers completed the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Preschool Version (BRIEF-P; Gioia, Espy, & Isquith, 2003), an 86-item parent questionnaire that assesses multiple domains of a child’s executive functioning, such as behavioral inhibition, attentional shift, emotional control, and working memory. The preschool version was administered because items were more appropriate for the nonverbal mental ages of the participants with DS. Because a number of participants fell outside of the norming sample, the raw total composite score was used in analyses, consistent with prior studies examining executive functioning in individuals with DS (Daunhauer et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2011; Liogier d’Ardhuy et al., 2015).

Analysis Plan

The first aim of this study was to identify pragmatic language profiles of boys and girls with DS at Visit 1, when the most pragmatic data were available. Analyses of Covariance (ANCOVAs), controlling for mental age and all measures of structural language (expressive and receptive vocabulary and MLU), were conducted to examine group differences across measures at Visit 1. The exception to this approach was comparisons on structural language subscales of the CCC-2, which controlled for nonverbal mental age only. Analyses were conducted within sex (i.e., girls with DS compared to TD girls) and within diagnostic group (i.e., boys with DS compared to girls with DS). To address floor effects, age equivalents were only calculated in cases where they could be accurately estimated (i.e., those with a raw score of 0 were not included in analyses).

The second aim of the study was to examine developmental trajectories of pragmatic language over time. To address this aim, exploratory hierarchical linear models were conducted with chronological age (the marker of change over time) nested within individual participant in order to examine the main effect of chronological age, group, and group by age interactions for CASL age equivalents and PRS-SA total pragmatic language violations. It is important to note that the small sample size included in these analyses may have impacted results and thus results should be considered exploratory. CCC-2 scores were not included in these analyses because of the small sample size beyond Visit 1. Nonverbal mental age, receptive vocabulary age equivalence, and mean length of utterance, grand-mean centered, were included as covariates in CASL analyses (EVT was not administered at Visit 2, so was not included), and all of these covariates plus expressive vocabulary age equivalence were included in the model for PRS-SA. Covariates were grand-mean centered in order to reduce collinearity amongst covariates and also to ensure that main effects would be estimated at the means of these variables. Random intercepts were included in the CASL model but all other effects were fixed. For the PRS-SA an attempt was made to fit a random intercept but this random intercept was excluded due to lack of variance and thus only fixed effects were included in the model. The hierarchical model for the PRS-SA total was followed up by repeated measures within boys and girls with DS examining change in individual items from Visit 1 to Visit 3.

Finally, to explore abilities related to pragmatics across time points, correlations were conducted. This included separate bivariate correlations for each group at each time point, examining potential relationships between the primary outcome variables (CCC-2 Global Composite, CASL age equivalence, and PRS-SA Total) and vocabulary, MLU, nonverbal mental age, theory of mind, and executive functioning. Additionally, partial correlations were completed, replicating previously described analyses between the primary outcome variables and theory of mind and executive functioning. Given the strong associations between PPVT, EVT, MLU, and mental age, only MLU and mental age were selected to be included as covariates in partial correlations. Correlations did not control for multiple comparisons given the exploratory nature of these analyses.

Results

Profiles of Pragmatic Skills in Children With DS at Visit 1

Group differences

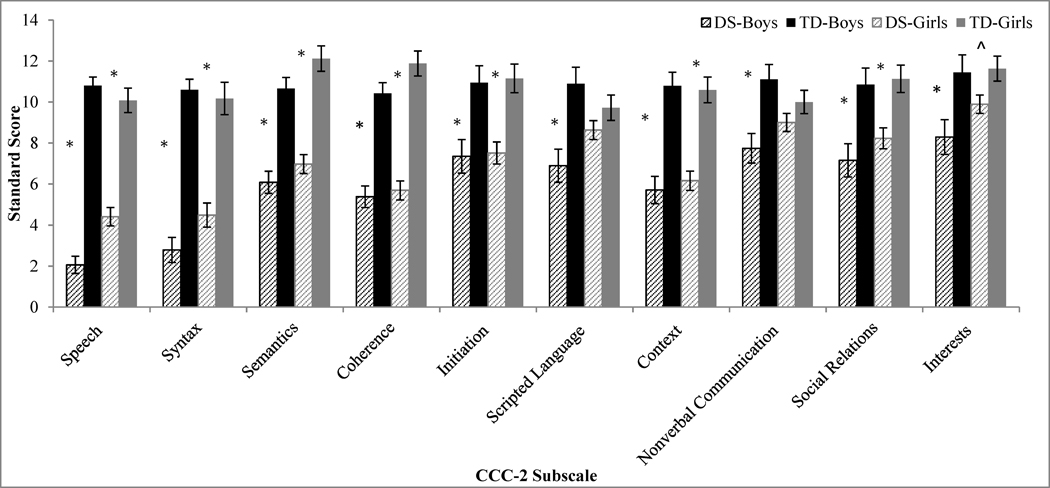

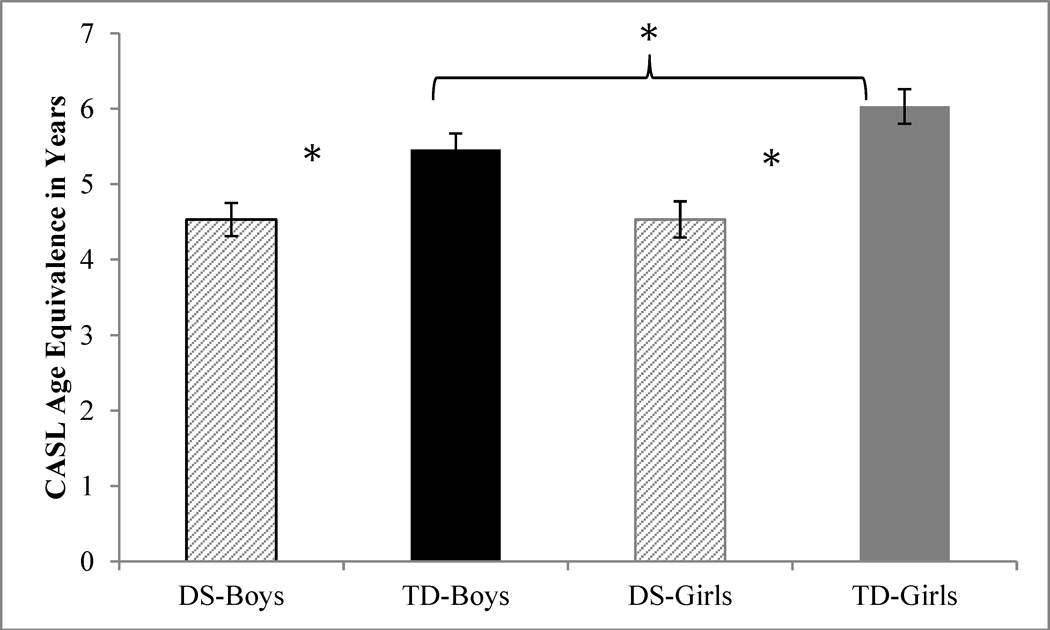

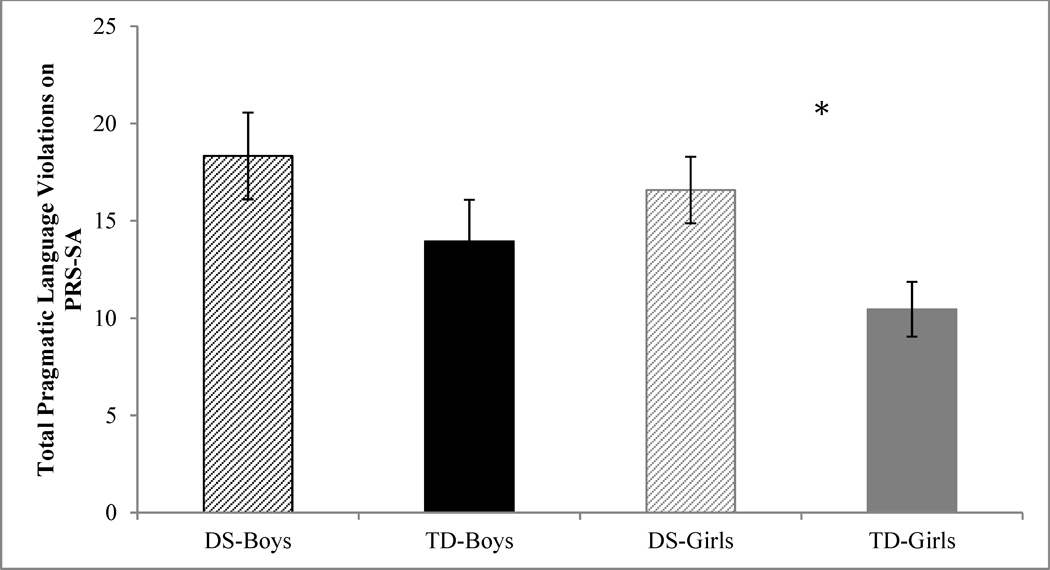

Both boys and girls with DS showed greater difficulty on the general composite of the CCC-2 relative to TD controls (F(1,21) = 22.34, p < .001; F(1,25) = 33.17, p < .001), as well as on nearly all subscales of the CCC-2 (Fs range from 3.90 to 211.68, ps < .05; with a marginal difference for Interests for girls with DS, p = .058), with the exception that girls with DS did not differ from girls with TD on the domains of nonverbal communication or scripted language (ps > .2) see Figure 1). Similarly, both boys and girls with DS demonstrated significantly lower age equivalents on the CASL relative to same sex typically developing controls (F(1,36) = 6.79, p = .013; F(1,40) = 16.44, p < .001, see Figure 2). Analyses compared PRS-SA totals based ADOS module (e.g., lower vs. higher language demand); total violations did not differ as a function of module (t(96) = .72, p = .47) and thus results are reported combined across modules. In contrast to findings on the parent questionnaire and standardized measure, when comparing PRS-SA total ratings, boys with DS did not significantly differ in their rates of pragmatic violations relative to TD boys (F(1,31) = 1.44, p = .24, see Figure 3). However, girls with DS committed significantly greater total pragmatic violations relative to girls with TD (F(1,27) =5.49, p = .03, see Figure 3). We further examined group differences on individual items of the PRS-SA in order to determine those specific items that distinguished boys and girls with DS from their respective same-sex control groups, summarized in Table 3. Boys with DS demonstrated greater rates of scripted or repetitive speech, unintelligible speech, as well as reduced intonation relative to boys with TD, whereas boys with TD interrupted their conversational partner more than boys with DS. Girls with DS demonstrated greater difficulty with being overly detailed, quality of reciprocal conversation, scripted/stereotyped speech and greater rates of unintelligibility relative to TD girls.

Figure 1.

Profile of differences on the CCC-2 subscales

Note. Means of speech, syntax, semantics and coherence are adjusted for mental age; all other scale means are adjusted for mental age, expressive and receptive vocabulary age equivalents, and MLU. * p < .05, ^ p < .1. (CCC-2=Children's Communicative Checklist, Second Edition; MLU=Mean Length of Utterance in Morphemes).

Figure 2.

Group differences in CASL age equivalence at Visit 1.

Note. CASL = Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language; DS = Down syndrome; TD = typically developing.

* p < .05.

Figure 3.

Group differences in total pragmatic violations on the PRS-SA.

Note. DS = Down syndrome; TD = typically developing; PRS-SA = Pragmatic Rating Scale-School Age.

* p < .05.

Table 3.

Profiles of individual PRS-SA items at visit 1

| TD Boys | DS Boys | TD Girls | DS Girls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overly Personal | .56 (.86) | .90 (.81) | .26 (.56) | 1.0 (1.04) |

| Swearing | .22 (.65) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Overly Talkative | .22 (.43) | .26 (.56) | .21 (.63) | .29 (.47) |

| Overly Detailed | .11 (.32) | 0 (0) | .11 (.32) | .29 (.61) |

| Insufficient Background Information | .83 (.79) | .84 (.76) | .79 (.71) | .86 (.77) |

| Redundant | .17 (.38) | .05(.23) | 0 (0) | .07 (.27) |

| Fails to Signal Humor | .06(.24) | 0 (0) | .11 (.46) | 0 (0) |

| Inadequate clarification | .61 (.78) | .16 (.37) | .16 (.37) | .14 (.36) |

| Topic Initiation | .11 (.47) | .53 (.90) | .32 (.75) | .57 (.94) |

| Inappropriate Topic Shifts | .44 (.86) | .53 (.90) | .32 (.75) | .71 (.99) |

| Intrusive Interrupting | .83 (.79) | .37 (.68) | .37 (.68) | .71 (.91) |

| Acknowledging | .22 (.55) | .58 (.84) | .42 (.77) | .64 (.84) |

| Response Elaboration | .22 (.43) | .79 (.71) | .47 (.61) | .86 (.95) |

| Topic Perseveration | .44 (.86) | .42 (.84) | .11 (.46) | .14 (.53) |

| Vocal Noises | .11 (.47) | .53 (.90) | .16 (.50) | .36 (.74) |

| Quality of Reciprocal Conversation | .22 (.43) | 1.05 (.85) | .84 (.60) | 1.43 (.65) |

| Overly Formal or Informal Speech | .22 (.55) | .26 (.56) | .11 (.46) | .14 (.53) |

| Scripted or Stereotyped Speech | .11 (.32) | .68 (.89) | .05 (.23) | 1.36 (.84) |

| Errors in Grammar/Vocabulary | 1.78 (.65) | 1.63 (.76) | 1.47 (.90) | 1.36 (.84) |

| Intelligibility | .22 (.43) | 1.58 (.51) | .32 (.48) | 1.21 (.58) |

| Rate | .33 (.77) | 1.05 (1.03) | 0 (0) | .29 (.73) |

| Intonation/Pitch | 0 (0) | .53 (.70) | .05 (.23) | .43 (.65) |

| Abnormal Volume | .72 (.75) | .68 (.89) | .79 (.79) | .71 (.91) |

| Use of Character Speech | 0 (0) | .11 (.46) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Language Formulation | 1.1 (1.02) | .53 (.90) | .11 (.46) | .29 (.73) |

| Stuttering/Cluttering | .11 (.47) | 1.16 (1.01) | .21 (.63) | .29 (.73) |

| Mismanagement of Personal Space | 1.17 (.79) | 1.63 (.76) | .84 (.96) | 1.57 (.65) |

| Gestures | .56 (.78) | .21 (.54) | .42 (.61) | .14 (.36) |

| Repetitive Body Movements | .39 (.70) | .42 (.84) | 0 (0) | .14 (.36) |

| Facial Expression | .11 (.47) | .11 (.46) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Eye Contact | .61 (.61) | .53 (.61) | .53 (.51) | 1.0 (.55) |

| Inappropriate Personal Hygiene | .11 (.47) | .84 (1.01) | .32 (.75) | .57 (.94) |

| Overall Total | 12.94 (7.3) | 18.95 (7.25) | 9.84 (4.54) | 17.57 (6.21) |

Note. DS = Down syndrome; TD = typically developing; PRS-SA = Pragmatic Rating Scale-School Age. Bolded items indicate areas of significant difference between TD and DS groups at p < .05. Italics represent areas of sex differences within diagnostic group. Non-adjusted means are reported for ease of interpretability. Analyses controlled for nonverbal mental age, receptive and expressive vocabulary, and mean length of utterance.

Sex differences

Girls with DS demonstrated nearly significantly greater overall standard scores on the CCC-2 than boys with DS (F(1,25) = 3.88, p = .060). Although there were no significant sex differences on any CCC-2 social subscales (ps > .2), girls with DS demonstrated better parent-reported intelligibility and syntax relative to DS boys (F(1,34) = 6.93, p = .013; F(1,33) = 3.54, p = .069). Girls with DS also did not significantly differ from boys with DS on CASL age equivalence or PRS-SA total pragmatic violations for individuals with DS (ps > .5). There were, however, several sex differences on individual items of the PRS-SA (see Table 3) for boys and girls with DS, in that girls with DS had greater difficulty with being overly detailed, higher frequency of inappropriate topic shifts, and reduced eye contact relative to boys with DS. Boys with DS demonstrated greater difficulty modulating rates of speech and higher frequency of stuttering than girls with DS.

There were also patterns of sex differences observed in the typically developing groups. On the CCC-2, boys and girls with TD did not differ overall or on any subscale (ps > .1) with the exception that girls with TD demonstrated nearly significantly greater coherence than boys with TD (F(1,25) = 3.79, p = .06). Girls with TD also demonstrated greater pragmatic age equivalence on the CASL relative to TD boys (F(1,40) = 5.24, p = .027), and demonstrated fewer pragmatic violations relative to boys with TD on the PRS-SA, though not reaching significance (F(1,31) = 1.91, p = .18). At the item level of the PRS-SA, TD boys had greater difficulty remedying communicative breakdowns and exhibited greater language formulation difficulties than girls with TD, whereas girls with TD demonstrated reduced conversational reciprocity relative to boys with TD (see Table 3).

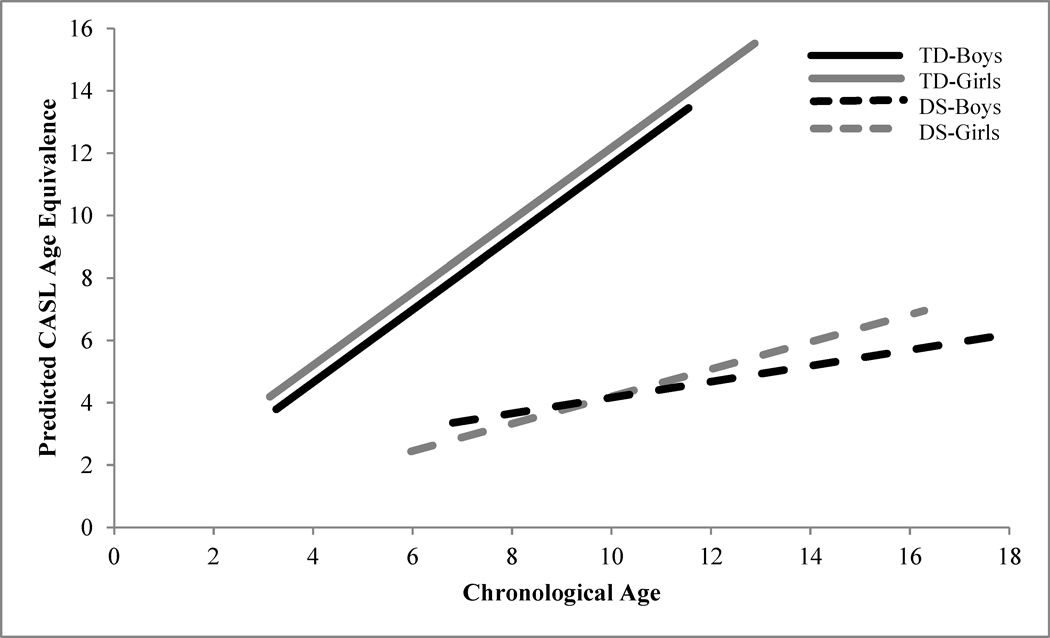

Development of Pragmatic Skills in Children With DS

Hierarchical Linear Model (HLM) results are presented in Table 4. The HLM results revealed a significant group by age interaction for CASL age equivalent scores. As demonstrated in Figure 4, boys and girls with DS developed at a significantly slower rate (slope = .065, standard error = .12 and slope = .14, standard error = .12, respectively) than boys and girls with TD (slope = .53, standard error = .13 and slope = .46, standard error = .11, respectively). There were no sex differences in rates of development for individuals with TD or DS.

Table 4.

Tests of Individual Effects for CASL and PRS-SA HLM

| Effects-CASL | |

|---|---|

| Chronological Age | F(1,138.08) = 17.36, p < .001 |

| Group | F(3,122.65) = 12.42, p < .001 |

| Group x Chronological Age | F (3,151.30) = 5.83, p = .001 |

| Mental Age | F(1,182.2) = 6.03, p = .015 |

| Receptive Vocabulary Age Equivalent | F (1, 167.00) = 29.04, p < .001 |

| MLU | F(1, 178.27) = 1.50, p = .22 |

|

| |

| Effects-PRS-SA | |

|

| |

| Chronological Age | F(1,50) =2.87. p = .10 |

| Group | F(1,50) = .05, p = .82 |

| Group x Chronological Age | F(1,50) =.003, p = .96 |

| Mental Age | F(1,50) = .24, p = .63 |

| Expressive Vocabulary Age Equivalent | F(1,50) = .31, p = .58 |

| Receptive Vocabulary Age Equivalent | F(1,50) = 2.44, p = .12 |

| MLU | F(1,50) = 1.49, p = .23 |

Note. CASL = Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language; PRS-SA = Pragmatic Rating Scale-School Age; MLU = mean length of utterance in morphemes; HLM = Hierarchical Linear Model; DS = Down syndrome; TD = typically developing.

Figure 4.

Changes in CASL Pragmatic Judgment Subscale Age Equivalence.

Note. CASL = Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language; DS = Down syndrome; TD = typically developing. Predicted CASL Age Equivalence derived from hierarchical linear models. Boys and girls with DS demonstrated significantly slower rates of development relative to controls. There were no sex differences in rates of development.

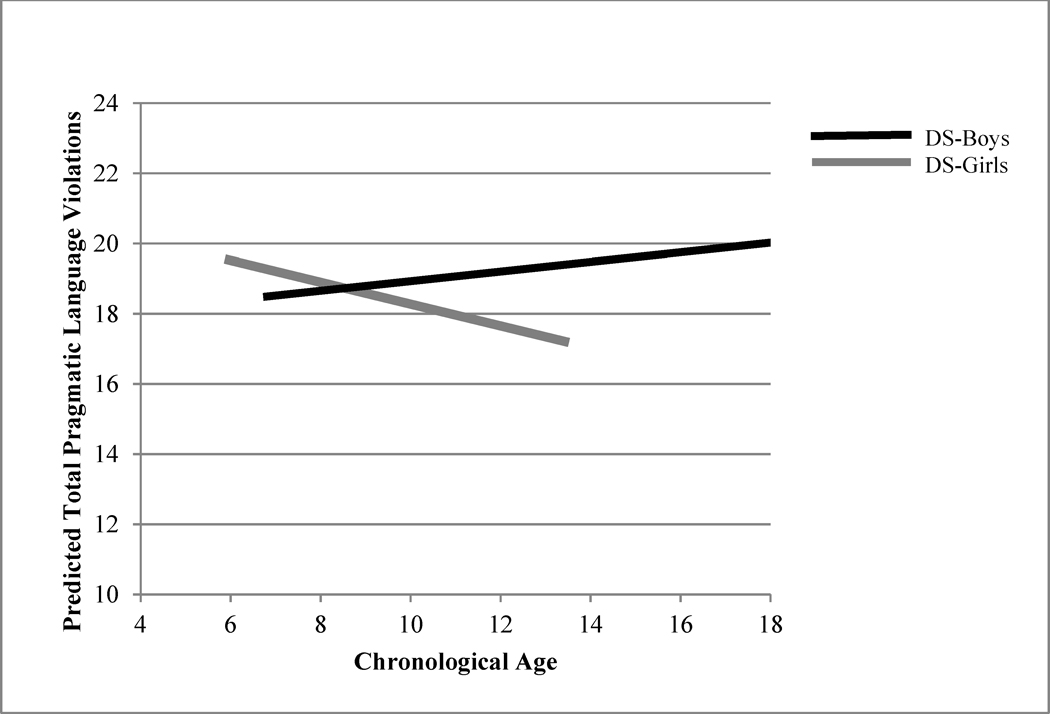

For PRS-SA in DS, results indicated that changes in PRS-SA totals increased (i.e., worsened) at a marginally significant rate with age, and that this rate of change did not differ between boys and girls (slope = .89, standard error = .48, slope = .85 standard error = .78, see Figure 5). We further examined patterns of performance on individual PRS-SA items to assess the types of pragmatic language violations committed over time and found that generally, individuals with DS demonstrated worsening of higher-level conversational skills [e.g., topic initiation and repetition of topics (i.e., redundancy), failure to signal humor, length of conversational turn; see Table 5]. At the same time, individuals with DS demonstrated improvements in nonverbal behaviors associated with pragmatics (e.g., appropriate use of personal space) and more fundamental conversational skills (e.g., reciprocal conversation, acknowledgement of the examiner).

Figure 5.

Development of total pragmatic violations on the Pragmatic Rating Scale-School Age.

Note. DS = Down syndrome; PRS-SA = Pragmatic Rating Scale-School Age. Mean PRS-SA total scores across chronological age derived from hierarchical linear models. Because ratings at multiple visits were only available for boys and girls with DS, only these groups are included in the model. There was a marginally significant effect of age indicating that boys and girls increased in impairments with chronological age; however, the inclusion of covariates resulted in a relative stability over time.

Table 5.

Means of PRS-SA items at visit one and visit three for individuals with DS with longitudinal data

| DS Boys Visit 1 |

DS Boys-Visit 3 | DS Girls-Visit 1 |

DS Girls-Visit 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overly Personal | .93 (.83) | 1.0 (.96) | 1.17 (1.03) | 1.08 (1.0) |

| Swearing | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Overly Talkative | .21 (.43) | .43 (.51) | .25 (.45) | 0.42 (79) |

| Overly Detailed | 0(0) | .14 (.36) | 0.17 (.39) | .58(.90) |

| Insufficient Background Information | .57 (.65) | 1.07 (.83) | 0.83 (.72) | 1.33 (.65) |

| Redundant | .07 (.27) | .50 (.65) | .08 (.29) | .33 (.65) |

| Fails to Signal Humor | 0(0) | .21 (.43) | 0 (0) | .25 (.62) |

| Inadequate clarification | .07 (.27) | .29 (.47) | .17 (.39) | .25 (.62) |

| Topic Initiation | .43 (.85) | .86 (1.02) | .67 (.98) | .50 (.90) |

| Inappropriate Topic Shifts | .57 (.94) | .71 (.99) | 0.83 (1.03) | 1.0 (1.04) |

| Intrusive Interrupting | .21 (.43) | .64 (.93) | 0.67 (.89) | 1.08 (1.0) |

| Acknowledging | .57 (.85) | .21 (.58) | .92 (.90) | .75 (.87) |

| Response Elaboration | .86 (.66) | .57 (.76) | 1.00 (.95) | 1.17 (.72) |

| Topic Perseveration | .57 (.94) | .71 (.99) | .17 (.58) | .33 (.78) |

| Vocal Noises | .43 (.85) | .36 (.74) | .42 (.79) | .25 (.62) |

| Quality of Reciprocal Conversation | 1.21 (.80) | .57 (.76) | 1.58 (.51) | 1.42 (.67) |

| Overly Formal or Informal Speech | .29 (.61) | .14 (.36) | .17 (.58) | .17 (.58) |

| Scripted or Stereotyped Speech | .93 (.92) | .29 (.73) | 1.58 (.67) | 1.17 (1.02) |

| Errors in Grammar/Vocabulary | 1.5 (.85) | 1.86 (.53) | 1.42 (.79) | 1.42 (.90) |

| Intelligibility | 1.50 (.52) | 1.36 (.63) | 1.33 (.49) | 1.08 (.67) |

| Rate | .86 (1.02) | 1.86 (.53) | 0.33 (.78) | 0 (0) |

| Intonation/Pitch | .64 (.74) | .50 (.65) | .42 (.67) | .17 (.39) |

| Abnormal Volume | .50 (.76) | .43 (.65) | .67 (.98) | .50 (.80) |

| Use of Character Speech | 0 (0) | .14 (.53) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Language Formulation | .29 (.73) | .57 (.94) | .33 (.78) | .33 (.78) |

| Stuttering/Cluttering | .86 (1.03) | 1.29 (.99) | .17 (.58) | .50 (.90) |

| Mismanagement of Personal Space | 1.71 (.73) | .79 (.98) | 1.58 (.67) | 1.42 (.90) |

| Gestures | .14 (.36) | .50 (.76) | .08 (.29) | .33 (.65) |

| Repetitive Body Movements | .43 (.85) | .36 (.74) | .08 (.29) | .08 (.29) |

| Facial Expression | .14 (.53) | .57 (.94) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Eye Contact | .50 (.65) | .29 (.61) | 1.08 (.67) | .75 (.62) |

| Inappropriate Personal Hygiene | .71 (.99) | .43 (.85) | .50 (.90) | .67 (.98) |

Note. PRS-SA = Pragmatic Rating Scale-School Age; DS = Down syndrome. Bolded items indicate significant changes over time at the level of p < .1.

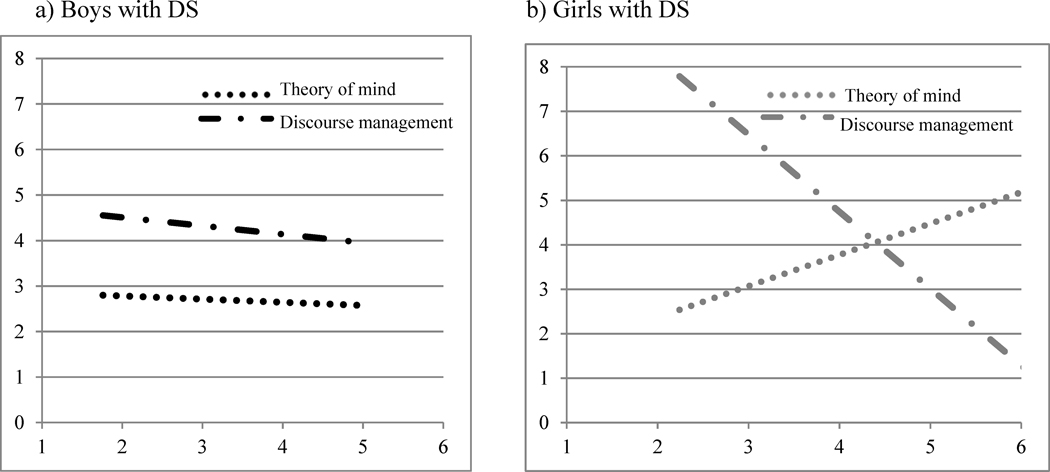

Finally, we explored how changes in pragmatic violations on the PRS-SA might relate to development of other skills. As demonstrated in Figure 6a–b, changes were qualitatively associated with changes in MLU. With increases in MLU, impairments associated with fundamental discourse management decreased in both boys and girls with DS. However, for girls with DS impairments in skills theoretically associated with theory of mind increased with increasing MLU.

Figure 6.

Qualitative relationships between mean length of utterance and items on the PRS-SA.

(a) Boys with DS (b) Girls with DS

Note. DS = Down syndrome; PRS-SA = Pragmatic Rating Scale-School Age. Figures demonstrate relationships between growth in mean length of utterance and domains of the PRS-SA, including theory of mind (e.g., length of turn and level of detail, appropriate referencing) and discourse management (e.g., reciprocal conversation, topic initiation) in boys (a) and girls (b) with DS.

Correlates of Pragmatic Language

For girls with DS and TD boys and girls, greater parent-reported impairments on the executive function measure, (BRIEF composite raw total score) were associated with greater parent-reported impairment on the overall CCC-2 composite (DS girls: r = −.62; TD boys r = −.74, TD girls r = −.76). These relationships held after controlling for mental age and MLU (DS girls r = −.65, TD boys r = −.72, TD girls r = −.74). Across groups and visits, better CASL performance was associated with greater mental age, receptive vocabulary, expressive vocabulary, and MLU (rs range from .50 to .95). For all groups at Visit 1, better theory of mind was significantly associated with improved performance on the CASL when mental age and MLU were not included as covariates in the model (rs > .51), there were also significant positive relationships for girls with DS and TD boys at Visit 2 (r = .54, r = .74). Once controlling for mental age and MLU, this relationship was significant for TD girls at Visit 1 and TD boys at Visit 2 (r = .57, r = .62) and for girls with DS approached significance for Visit 1 (r = .44, p = .06) and was significant at Visit 2 (r = .46). Greater impairment on the BRIEF composite was associated with increased impairment on the PRS-SA for boys with DS at Visit 1 (r = .76), even after controlling for mental age and MLU (r = .73). For girls with DS at Visit 3, greater MLU and receptive vocabulary age equivalence were associated with reduced rates of pragmatic language violations (r = −.69, r = −.65). Finally, for girls with TD, better theory of mind was associated with reduced total pragmatic violations on the PRS-SA at Visit 1 (r = −.60), a relationship that approached significance after controlling for receptive vocabulary and MLU (r = −.56, p = .06).

Discussion

This study used a longitudinal, multi-method design to explore pragmatic language profiles and related abilities in boys and girls with DS. Results suggest that pragmatic language represents an area of impairment for individuals with DS relative to typically developing individuals and revealed some evidence for sex specific patterns of pragmatic impairment. The pragmatic skills of individuals with DS were largely stable with age, although analyses suggest that the types of pragmatic impairments changed with age and language ability. Executive functioning, theory of mind, expressive and receptive vocabulary, MLU and nonverbal mental age all related to pragmatic language outcomes, although these relationships varied by assessment and type of pragmatic skill.

Overall, boys and girls with DS demonstrated global difficulties in pragmatic language relative to younger TD controls as measured by parent-report and standardized assessments, even after controlling for mental age and structural language abilities. This is consistent with prior work documenting weaker pragmatic language skills compared to TD controls (Laws & Bishop, 2004; Martin, G. E., et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2007; Tannock, 1988). However, differences were less striking on direct assessments of pragmatic language in boys with DS. This contrasts with findings from a prior cross-sectional study showing significant differences between boys with DS and TD (Klusek et al., 2014), who used similar pragmatic assessment methods with a partially overlapping but higher functioning sample than studied here. Whereas the Klusek et al. sample included a cross-sectional group of boys with DS selected to optimize matching with TD controls, with mean receptive vocabulary age equivalent of 5.93 and expressive vocabulary age equivalent of 5.89, the present longitudinal study included children’s data from Visit 1, when they exhibited less developed language (mean expressive vocabulary age equivalence = 5.33 and mean receptive vocabulary age equivalence = 5.15). Therefore, the discrepancy in findings suggests that with advancing language skills greater opportunities for committing pragmatic language violations may emerge. This possibility is supported by patterns observed in the current study, as several higher order pragmatic skills worsened for boys with DS over time, such as taking too lengthy of conversational turns or being redundant in topics introduced. Further, although the total number of violations did not differ between groups, boys with DS demonstrated significantly greater rates of certain types of impairment (e.g., repetitive speech), suggesting that global impairment scores may obscure specific areas of difficulty for both boys and girls with DS.

This study was one of the first to assess sex-specific profiles of pragmatic language in children with DS, and although based only on a small sample, results suggest that sex may impact aspects of pragmatic language in DS. In contrast to our hypothesis and the Berglund et al. (2001) finding that parents reported fewer pragmatic impairments in girls with DS relative to boys, girls with DS did not demonstrate any advantage relative to boys with DS, and in fact demonstrated greater rates of impairment in several specific pragmatic skills (e.g., making eye contact, being overly detailed) as compared to boys with DS. Our sample was considerably older than Berglund’s sample (ages 1–5 years), suggesting that sex differences may vary as a function of chronological age and developmental level. Further, females with DS exhibited significantly greater rates of pragmatic violations relative to their TD control group. In contrast to direct ratings of pragmatic behaviors, girls with DS did not differ from same-sex typically developing controls on parent reported use of nonverbal communication or repetitive language. The profile of differences in girls with DS relative to their same sex control group has important implications for intervention planning, as direct clinical rating results suggest that girls with DS may demonstrate more prominent difficulties during everyday, same-sex peer interactions that may not be detected based on parent-report alone. In effect, given that girls with DS do not show the same pragmatic advantages relative to boys with DS that are observed in typical development, the gap in pragmatic competence between girls with DS and girls with TD may be even wider than those observed in DS and TD boys, posing greater challenges for girls with DS in social and educational settings. Though results should be interpreted with caution given our relatively small sample size, future studies should continue to delineate the pragmatic profile of girls with DS with the goal of developing sex-specific clinical and educational supports.

A second aim of this study was to explore trajectories of pragmatic language development over time in boys and girls with DS. Replicating prior work with boys with DS (Martin, G. E., et al., 2013), we found that on a standardized assessment that assesses the ability to identify pragmatically appropriate responses in a range of social situations (the CASL), both boys and girls with DS demonstrated a slower rate of growth compared to TD controls. Further, clinical ratings of pragmatic behaviors in the semi-naturalistic conversational context (the PRS-SA) indicated that individuals with DS demonstrated a marginal increase in pragmatic language violations with chronological age. In contrast to our hypotheses, no sex differences were observed in these rates over time. Prior work examining skills such as adaptive functioning, receptive vocabulary, and grammatical abilities suggests variable patterns of development in DS, with reduced predictive relationships between age and ability, or even declines in later adolescence and adulthood (Cuskelly, Povey & Jobling, 2016; de Graaf & de Graaf, 2016; Dykens et al., 2006). Perhaps, then, current results reflect a more general tendency during school age for pragmatic abilities of individuals with DS to stabilize. These findings should be interpreted with some caution given the small sample size included in the current work. Additional studies with larger sample sizes are needed to comprehensively assess pragmatic language from young ages to adulthood in individuals with DS, to confirm patterns of change observed in the current study, and in particular to clarify relationships between development of pragmatic language and growth or stability in related domains. Nevertheless, this study offers important preliminary findings characterizing trajectories of pragmatic language development for individuals with DS.

Although pragmatic development was relatively stable on standardized measures and overall clinical-behavioral ratings of conversational samples, patterns of change in specific types of pragmatic language violations in individuals with DS were observed. In particular, whereas individuals with DS demonstrated patterns of improvement in more fundamental aspects of pragmatic language (e.g., conversation) and demonstrated some reduced problem behaviors (e.g., not managing personal space), they demonstrated increasing difficulty within other, arguably more complicated pragmatic aspects of pragmatic behavior, such as providing adequate background when introducing new topics. This changing profile in the pragmatic skills posing challenges to individuals with DS over time appeared to be linked to increases in MLU, particularly for girls with DS. Therefore, it may be that as individuals with DS make gains in syntactic ability a “trade-off” in pragmatic competence occurs, in that greater structural language skills afford opportunities to make more fundamental conversation contributions, but also bring about greater conversational challenges and opportunities to demonstrate more atypical conversational behaviors.

Finally, correlates of pragmatic language varied as a function of the assessment method and pragmatic skills assessed. Performance on the standardized assessment (the CASL) was most strongly associated with structural language and general cognitive abilities. Consistent with Losh et al. (2012), theory of mind was also associated with performance on the standardized assessment across diagnostic groups and sex, highlighting the importance of theory of mind in the more abstract understanding of appropriate pragmatic language behaviors. Findings indicating that associations diminished when controlling for mental age and MLU likely reflect the strong relationship between theory of mind and highlight the role of syntactic development in particular (de Villiers, 2007). For instance, De Mulder (2015) found that syntactic ability predicted the understanding of indirect requests (e.g. shivering to signal to another person that they should turn up the heat) in TD children. This suggests that language, and in particular syntactic knowledge, can demonstrate a bidirectional relationship with theory of mind in both TD and DS.

In contrast, executive functioning was the primary correlate on parent-report and clinical ratings from semi-naturalistic conversational interactions. This suggests that in everyday interactions, which rely heavily on attention, memory, and planning, executive function plays an instrumental role in pragmatic language, above and beyond language and cognitive abilities, and that deficits in this domain may play an important role in the underlying causes of pragmatic deficits in DS observed in more naturalistic contexts. These findings are consistent with prior work demonstrating relationships between executive functioning and pragmatic language both in typical development and clinical populations such as autism spectrum disorder (e.g., Gooch et al., 2016; Helland, Lundervold, Heimann, & Posserud, 2014; Martin, I., & McDonald, 2003; McEvoy, Rogers, & Pennington, 1993; Pennington & Ozonoff, 1996). For example, Blain-Briere, Bouchard, and Bigras (2014) found that executive function (i.e., self-control, inhibition, flexibility, working memory, and planning) contributes more to pragmatic skills than full scale IQ in young typically developing children. An important focus for future work will be to determine the role of specific executive skills in different aspects of pragmatic language impairment in DS. For instance, working memory, a documented deficit in individuals with DS (Lanfranchi et al., 2010), could impact the ability to process on-line social information in conversational contexts, perhaps resulting in behaviors noted among the DS group, such as increased repetitive or “scripted” (i.e., repeated from another source) language.

Together, associations between pragmatic competence and structural language, executive function, and theory of mind across measures highlight the importance for clinical assessment to consider associated abilities, in order to pinpoint origins of pragmatic impairment and support the development of tailored interventions for children with DS. This will enable clinicians to address key skills contributing to pragmatic impairment as part of the treatment process, helping individuals with DS improve upon the range of tools necessary for engaging in complex pragmatic interactions. For example, interventions supporting executive functioning skills may also support pragmatic language development by increasing an individual’s ability to attend to interactions, inhibit potentially conversationally inappropriate behavior, and more efficiently process social information.

The measures included in this study varied in terms of assessment context and skills assessed. For example, whereas the standardized measure required individuals to generate judgments of appropriate pragmatic behaviors in a structured context with supportive illustrations (involving relatively low executive demands), both parent-report and clinical ratings of semi-naturalistic conversational interactions capture a broader range of social communicative skills observed during interactions. Therefore, it is possible that standardized assessments of pragmatic language draw more on global cognitive abilities and structural language, while pragmatic difficulties apparent during semi-naturalistic interactions may be more closely related to executive dysfunction. Further, the pragmatic skills tapped by each measure vary considerably. For example, the standardized measure (CASL) requires one to generate an appropriate response but does not account for execution of the response (e.g., tone of the response, nonverbal communication integrated with the response). The CCC-2 and PRS-SA both capture conversational pragmatic difficulties, but in different ways, with the CCC-2 providing a global picture of everyday functioning provided by parents and the PRS-SA providing more fine-grained assessment of multiple abilities within a single conversational context, rated by individuals trained in pragmatic language assessment. It will be important for future work to continue to document profiles of pragmatic language across different assessment methods and contexts in order to understand how pragmatic language is impacted in DS, and to develop tailored interventions to support social communication in everyday settings for individuals with DS across development. A fruitful approach in future studies may be to examine domains of pragmatic abilities across measures, rather than relying on a single score on a given measure, given the unique perspective each approach provides to characterizing pragmatics in DS.

In conclusion, results from this longitudinal, multi-method study of pragmatic language in boys and girls with DS suggest that despite their well-documented sociability and outgoing personalities, individuals with DS demonstrate pragmatic language difficulties relative to a younger TD control group and develop these skills at slower rates over time. Different assessment approaches offered unique insights as to the strengths and weaknesses of individuals with DS, as well as how sex, structural language, mental age, theory of mind, and executive functioning underlie these abilities throughout development. Future work should continue to characterize pragmatic development throughout the lifespan in larger samples of both boys and girls with DS.

Acknowledgments

Funding support was provided by R01 HD038819, R01 HD044935, R01MH091131-01A1, 1R01DC010191-01A1, DGE-1324585. This manuscript has not been presented elsewhere. We gratefully acknowledge Anne Taylor and Abigail Hogan for their support in coding files, and Jan Misenheimer for her assistance with data management. We sincerely thank all participating families.

Contributor Information

Michelle Lee, Northwestern University.

Lauren Bush, Northwestern University.

Gary E. Martin, St. John’s University

Jamie Barstein, Northwestern University.

Nell Maltman, Northwestern University.

Jessica Klusek, University of South Carolina.

Molly Losh, Northwestern University.

References

- Abbeduto L, Brady N, Kover ST. Language development and fragile X syndrome: profiles, syndrome-specificity, and within-syndrome differences. Mental Retardation Developmental Disabilities Research Review. 2007;13(1):36–46. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20142. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1002/mrdd.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbeduto L, Chapman R. Language development in Down syndrome and fragile X syndrome: Current research and implications for theory and practice. In: Fletcher P, Miller JF, editors. Developmental theory and language disorders. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Co.; 2005. pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Abbeduto L, Murphy MM, Kover ST, Karadottir S, Amman A, Bruno L. Signaling noncomprehension of language: A comparison of fragile X syndrome and Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113:214–230. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2008)113[214:SNOLAC]2.0.CO;2. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1352/0895-8017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American-Speech-Language-Hearing Association. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Website. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.asha.org.

- Berghout Austin AM, Salehi M, Leffler A. Gender and developmental differences in children's conversations. Sex Roles. 1987;16(9–10):497–510. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1007/bf00292484. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund E, Eriksson M, Johansson I. Parental reports of spoken language skills in children with Down syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001;44(1):179–191. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/016). http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1044/1092-4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman R, Slobin D. Relating events in narrative: A cross-linguistic developmental study. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D. The Children's Communication Checklist-2. London, UK: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM. Children’s Communication Checklist-2, United States Edition, Manual. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D. CCC-2. In: Volkmar FR, editor. The encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders. New York, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blain-Brière B, Bouchard C, Bigras N. The role of executive functions in the pragmatic skills of children age 4–5. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:240. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Levinson SC. Politeness: some universals in language usage. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. A first language: The early stages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J. Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Carrow-Woolfolk E. CASL: Comprehensive assessment of spoken language. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cebula KR, Moore DG, Wishart JG. Social cognition in children with Down's syndrome: Challenges to research and theory building. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research. 2010;54(2):113–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01215.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7750(07)35002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook AS, Fritz JJ, McCornack BL, Visperas C. Early gender differences in the functional usage of language. Sex Roles. 1985;12(9–10):909–915. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00288093. [Google Scholar]

- Cuskelly M, Povey J, Jobling A. Trajectories of development of receptive vocabulary in individuals with Down syndrome. Journal of Policy & Practice in Intellectual Disabilities. 2016;13(2):111–119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12151. [Google Scholar]

- Daunhauer LA, Fidler DJ, Hahn L, Wil E, Lee NR, Hepburn S. Profiles of everyday executive functioning in young children with Down syndrome. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2014;119(4):303–318. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-119.4.303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-119.4.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf G, de Graaf E. Development of self-help, language, and academic skills in persons with Down syndrome. Journal of Policy & Practice in Intellectual Disabilities. 2016;13(2):120–131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12161. [Google Scholar]

- De Mulder H. Developing communicative competence: A longitudinal study of the acquisition of mental state terms and indirect requests. Journal of Child Language. 2015;42(5):969–1005. doi: 10.1017/S0305000914000543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0305000914000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers J. The interface of language and theory of mind. Lingua. 2007;117(11):1858–1878. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2006.11.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn DM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Third Edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn DM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Assessments; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dykens E, Hodapp RM, Evans DW. Profiles and development of adaptive behavior in children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 2006;9:45–50. doi: 10.3104/reprints.293. http://dx.doi.org/10.3104/reprints.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbretti D, Pizzuto E, Vicari S, Volterra V. A story description task in children with Down's syndrome: Lexical and morphosyntactic abilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1997;41(Pt 2):165–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finestack LH, Palmer M, Abbeduto L. Macrostructural narrative language of adolescents and young adults with Down syndrome or fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2012;21:29–46. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0095). http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0095) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske S, Taylor S. Social cognition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. The measurement of interrater agreement. In: Shewart WA, Wilks SS, editors. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2004. pp. 598–626. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia GA, Espy KA, Isquith PK. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Preschool Version (BRIEF-P) Lutz, FL: PAR; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason JB, Ratner NB. The development of language. 8. New York, NY: Pearson; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gooch D, Thompson P, Nash HM, Snowling MJ, Hulme C. The development of executive function and language skills in the early school years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2016;57(2):180–187. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12458. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik A, Meltzoff AN, Kuhl PK. The scientist in the crib: Minds, brains, and how children learn. New York, NY: Morrow; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grice HP. Logic and conversation. In: Cole P, Morgan JL, editors. Syntax and semantics 3: Speech acts. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1975. pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Helland WA, Lundervold AJ, Heimann M, Posserud MB. Stable associations between behavioral problems and language impairments across childhood-The importance of pragmatic language problems. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35(5):943–951. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.02.016. http://dx.doi.org/.10.1016/j.ridd.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan-Brown AL, Losh M, Martin GE, Mueffelmann D. An investigation of narrative ability in boys with autism and fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2013;118(2):77–94. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-118.2.77. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1352/1944-7558-118.2.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John AE, Mervis CB. Comprehension of the communicative intent behind pointing and gazing gestures by young children with Williams syndrome or Down syndrome. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2010;53(4):950–960. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0234). http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0234) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston F, Stansfield J. Expressive pragmatic skills in pre-school children with and without Down's syndrome: Parental perceptions. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research. 1997;41(Pt 1):19–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller-Bell YD, Abbeduto L. Narrative development in adolescents and young adults with fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2007;112:289–299. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[289:NDIAAY]2.0.CO;2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[289:NDIAAY]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klusek J, Losh M, Martin GE. A comparison of pragmatic language in boys with autism and fragile X syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2014;57(5):1692–1707. doi: 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-13-0064. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-13-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothari R, Skuse D, Wakefield J, Micali N. Gender differences in the relationship between social communication and emotion recognition. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(11):1148–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.08.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa R. Pragmatic Rating Scale for School-Age Children (PRS-SA) Unpublished manual; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2529310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfranchi S, Jerman O, Dal Pont E, Alberti A, Vianello R. Executive function in adolescents with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research. 2010;54(4):308–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01262.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws G, Bishop D. Pragmatic language impairment and social deficits in Williams syndrome: A comparison with Down's syndrome and specific language impairment. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2004;39(1):45–64. doi: 10.1080/13682820310001615797. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820310001615797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaper C. Influence and involvement in children's discourse: Age, gender, and partner effects. Child Development. 1991;62(4):797–781. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01570.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NR, Fidler DJ, Blakeley-Smith A, Daunhauer L, Robinson C, Hepburn SL. Caregiver report of executive functioning in a population-based sample of young children with Down syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2011;116(4):290–304. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-116.4.290. http://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-116.4.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Mitchell P, editors. Children’s early understanding of mind. East. Sussex, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Liogier d’Ardhuy X, Edgin JO, Bouis C, de Sola S, Goeldner C, Kishnani P, Khwaja O. Assessment of cognitive scales to examine memory, executive function and language in individuals with Down Syndrome: Implications of a 6-month observational study. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2015;9:300–311. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00300. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DeLavore PC, Risi S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Losh M, Martin GE, Klusek J, Hogan-Brown AL, Sideris J. Social communication and theory of mind in boys with autism and fragile X syndrome. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00266. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GE, Klusek J, Estigarribia B, Roberts JE. Language characteristics of individuals with Down syndrome. Topics in Language Disorders. 2009;29(2):112–132. doi: 10.1097/tld.0b013e3181a71fe1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0b013e3181a71fe1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GE, Losh M, Estigarribia B, Sideris J, Roberts J. Longitudinal profiles of expressive vocabulary, syntax, and pragmatic language in boys with fragile X syndrome or Down syndrome. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2013;48(4):432–443. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GE, Roberts JE, Helm-Estabrooks N, Sideris J, Assal J. Perseveration in the connected speech of boys with fragile X syndrome with and without autism spectrum disorder. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;117(5):384–399. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.5.384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-117.5.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin I, McDonald S. Weak coherence, no theory of mind, or executive dysfunction? Solving the puzzle of pragmatic language disorders. Brain and Language. 2003;85(3):451–466. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(03)00070-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-934X(03)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews R, Dissanayake C, Pratt C. The relationship between the theory of mind and conservation abilities in children using active/inactive paradigm. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2003;55:35–4210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00049530412331312854. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy RE, Rogers SJ, Pennington BF. Executive function and social communication deficits in young autistic children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34(4):563–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01036.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JF, Chapman RS. Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moore DG, Oates JM, Hobson PR, Goodwin JE. Cognitive and social factors in the development of infants with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 2002;8:172–188. doi: 10.3104/reviews.129. http://dx.doi.org/10.3104/reviews.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K. How children represent knowledge of their world in and out of language: A preliminary report. In: Siegler RS, editor. Children's thinking: What develops? Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. pp. 255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, Correa A. Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2010;88(12):1008–1016. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20735. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bdra.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington BF, Ozonoff S. Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1996;37(1):51–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01380.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porto-Cunha E, Limongi SC. Communicative profile used by children with Down syndrome. Pro Fono. 2008;20(4):243–248. doi: 10.1590/s0104-56872008000400007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-56872008000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pueschel SM. Down syndrome. In: Zuckerman B, Parker S, editors. Behavioral and developmental pediatrics: A handbook for primary care. New York, NY: Little Brown; 1995. pp. 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Martin GE, Moskowitz L, Harris AA, Foreman J, Nelson L. Discourse skills of boys with fragile X syndrome in comparison to boys with Down syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:475–492. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH, Miller LJ. Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised. Wood Dale, IL: Stoelting; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roizen NJ. Down syndrome. In: Batshaw ML, Roizen NJ, Pellegrino L, editors. Children with disabilities. 6. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 2007. pp. 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman CK, Holtz KD. Gender differences in preschool children's commentary on self and other. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2013;174(2):192–206. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2012.662540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter V, Peterson CC, Mackintosh E. Mind what mother says: Narrative input and theory of mind in typical children and those on the autism spectrum. Child Development. 2007;78(3):839–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01036.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares EMF, de Britto Pereira MM, Sampaio TMM. Pragmatic ability and Down's syndrome. Revista CEFAC. 2009;11(4):579–586. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber D, Wilson D. Pragmatics, modularity, and mind-reading. Mind & Language. 2002;17(1):2–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-0017.00186. [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H, Anderson M. The development of contingent discourse ability in autistic children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1991;32:1123–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00353.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H, Rogers S, Cooper J, Landa R, Lord C, Paul R, Yoder P. Defining spoken language benchmarks and selecting measures of expressive language development for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:643–652. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0136). http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0136) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]