Practical Implications

Consider rituximab as a possible treatment for combined central and peripheral demyelination.

Combined central and peripheral demyelination (CCPD) is a rare autoimmune demyelinating disorder affecting both CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS). Prevalence is probably underestimated, since in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS)–like forms the PNS involvement is frequently undetected. The pathogenesis is largely unknown, prognosis is poor, and treatment options, including steroids and IV immunoglobulins (IVIg), are limited and almost ineffective.1–3

The following case was previously reported in a larger cohort of patients with CCPD (patient 16).2

Case Report

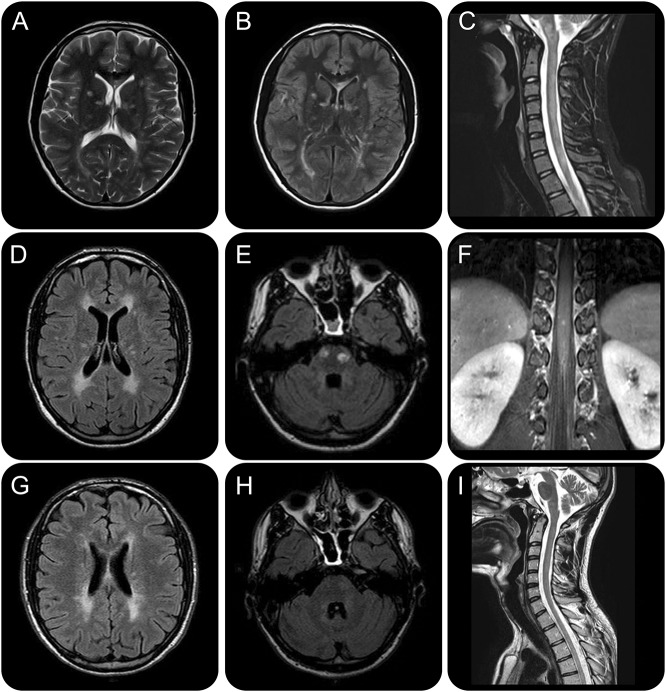

A 14-year-old boy presented with a subacute onset of irritability, ascending asymmetric paresthesia in the lower limbs, and ataxic gait, evolving over 5 weeks after a flu-like syndrome. Neurologic examination revealed normal tone and strength, areflexia in lower limbs, bilateral Babinski sign, reduced light touch, pinprick, and joint position sense at ankles, and ataxia with positive Romberg sign (Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS] 2.5). MRI revealed multiple T2-weighted periventricular and deep white matter lesions, some of which showed contrast enhancement, along with longitudinally extensive and multiple cervicodorsal spinal cord lesions (figure 1, A–C) and cauda equina roots hypertrophy. Nerve conduction study (NCS) disclosed reduced sensory and motor conduction velocities, F-response latency prolongation, conduction blocks, and temporal dispersion of motor potentials at 4 limbs (figure e-1 at Neurology.org/cp). These latter findings fulfilled the 2010 European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society electrodiagnostic criteria for definite demyelinating neuropathy.4 CSF analysis showed pleocytosis (11 lymphomonocytes/mm3), hyperproteinorrachia (56.7 mg/dL; normal values 15–45 mg/dL), mild blood–CSF brain barrier damage (albumin transfer 1.3%; normal value <0.7%), and no oligoclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) bands (OCB). Blood and CSF metabolic, autoimmune, and infectious workup for common inflammatory and demyelinating diseases was normal (table e-1). Anti-GQ1b (immunoDOT assay), anti-neurofascin-155 (ELISA and cell-based assay), anti-AQP4, and anti-MOG antibodies (cell-based assays) were negative. Eventually, diagnosis of CCPD was made.

Figure 1. Brain and spine MRI findings at baseline, after natalizumab discontinuation, and at 12-month follow-up after rituximab administration.

Brain and spine MRI findings at baseline (A–C), after natalizumab discontinuation (D–F), and at 12-month follow-up after rituximab administration (G–I), and EDSS timeline. Baseline T2-weighted (A) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (B) axial brain sections highlight multiple hyperintense signal alterations mainly in subcortical and periventricular white matter and corpus callosum, associated with a T2-hyperintense cervical spinal cord lesion extending longitudinally from C2 to C7 (C) and other smaller dorsal lesions (D1 and D7–D8) and cauda equina roots hypertrophy. Diffuse signal alterations were also found in cerebellum and brainstem (not shown): these findings globally fulfilled the 2010 revised multiple sclerosis (MS) criteria for dissemination in space and time, although longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis and cauda equina involvement are highly atypical and made the diagnosis of MS unlikely. After an initial clinical and neuroradiologic improvement with natalizumab, the patient experienced a new severe relapse with prominent peripheral nervous system (PNS) deterioration and new brain (i.e., periventricular white matter, corpus callosum, internal capsule, pons) (D) and dorsal-lumbar spine lesions with contrast enhancement on MRI. Therapy was therefore discontinued. Brain axial FLAIR image highlights 2 ovoid hyperintense signal alterations in the pons (E); spine coronal T1-weighted image shows cauda nerve roots and conus medulla lesions with contrast enhancement (F). We decided to start rituximab as a third-line rescue treatment; clinical response on both CNS and PNS was rapid and persistent. MRI after 12 months of clinical stability evidenced a global reduction in volume and number of the demyelinating lesions, without new signal alterations. Brain axial FLAIR images highlight slight reduction of anterior periventricular white matter lesions (G) and marked reduction of the pons lesions (H). Spine sagittal T2-weighted image shows great improvement of the cervical lesion (I).

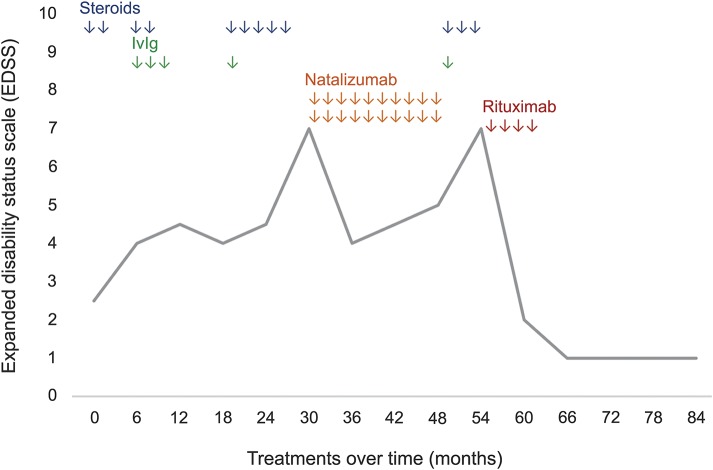

Over the following 30 months, the patient experienced several clinical relapses (mean 8/year), involving predominantly CNS or PNS, and mainly characterized by worsening of sensory ataxia, distal weakness, and paresthesia at 4 limbs. OCB were persistently absent. Therapy with either high-dose pulse IV methylprednisolone (IVMP) (9 cycles) with oral tapering or IVIg (4 administrations overall, at 2 g/kg divided into 5 daily doses) was performed. Nevertheless, brain and spine lesion burden on MRI gradually increased, with only partial and transitory clinical remissions.

As the patient's clinical condition gradually deteriorated (EDSS 7) (figure 2), the parents referred him to a different center. Although presenting with atypical features, the patient was there considered to fulfill the 2010 Polman criteria for MS.5 According to the European Medicine Agency Eligibility 1b Criteria for rapidly evolving severe relapsing-remitting disease, he was therefore started on the anti-α(4)-integrin monoclonal antibody natalizumab. After 13 months of partial clinical and neuroradiologic improvement, the patient relapsed, presenting again with progressive dysphagia, disabling sensory-cerebellar ataxia, distal motor weakness, and hypoparesthesias. NCS measures showed considerable worsening (figure e-2). Hence, natalizumab was discontinued after 20 cycles overall.

Figure 2. Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) timeline.

The figure shows the temporal course of the patient's disability (EDSS) in relation to different treatments performed over time. Rituximab was dramatically effective in improving clinical disability, with persistent effect during the following 28 months of follow-up.

The patient returned to our observation with an EDSS score of 7. Brain and spine T2 lesion burden at MRI was markedly increased (figure 1, D–F). A further attempt with 3 IVMP cycles and 1 IVIg administration was ineffective. Therefore, the patient was started on the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, whose efficacy has been reported in both MS and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.6,7 A dose of 500 mg/wk for 4 weeks was administered. Sensory and motor deficits gradually improved over about 8 months. The patient remained stable with only mild residual proprioceptive impairment thereafter (EDSS 1), without relapses during the 28-month follow-up period. Brain and spine MRI performed at 18 months revealed reduction in the lesion burden, without new inflammatory lesions (figure 1, G–I). For the first time since the clinical onset, we noticed a dramatic improvement of nerve conduction parameters, with a near normalization of motor conduction velocities and disappearance of conduction blocks (figure e-3). Therapy was well-tolerated. The only side effect was transient secondary hypogammaglobulinemia that we treated with periodic IVIg replacement therapy for 8 months (IgG >500 mg/dL thereafter, with slow CD19+ B-cell recovery).

DISCUSSION

Our patient experienced several relapses of CCPD over a period of 7 years. As previously reported,1,3 treatment with IVMP and IVIg resulted in only partial and transient clinical improvement. Natalizumab led to limited neuroradiologic improvement, with severe PNS measures worsening and subsequent relapses. Rituximab was effective in our patient by clinically and radiologically improving both CNS and PNS damage and preventing new relapses.

With the limits of this single case observation with a medium-term follow-up, we suggest that rituximab should be considered as an effective therapy for the treatment of steroid- and IVIg-resistant CCPD.

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/cp

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S. Savasta: diagnosis, clinical follow-up, therapeutic management, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. T. Foiadelli: clinical assessment, data collection and interpretation, manuscript design. E. Vegezzi: manuscript design, data acquisition and analysis. A. Cortese: clinical assessment and critical revision for intellectual content. A. Lozza: electrophysiology investigations and NCS follow up, critical revision of figures and additional data. A. Pichiecchio: MRI investigations, critical revision of figures. D. Franciotta: laboratory investigations, CSF analyses, data collection. E. Marchioni: clinical assessment and follow up, therapeutic management, manuscript concept and design, critical revision for intellectual content.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

S. Savasta, T. Foiadelli, and E. Vegezzi report no disclosures. A. Cortese has received funding for travel from Biogen Idec, Genzyme, Novartis, Teva, and Kedrion and speaker honoraria from Pfizer. A. Lozza reports no disclosures. A. Pichiecchio has received speaker honoraria from Genzyme. D. Franciotta reports no disclosures. E. Marchioni receives research support from Fondazione Istituto Neurologico Casimiro Mondino. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamovic T, Riou EM, Bernard G, et al. Acute combined central and peripheral nervous system demyelination in children. Pediatr Neurol 2008;39:307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortese A, Franciotta D, Alfonsi E, et al. Combined central and peripheral demyelination: clinical features, diagnostic findings, and treatment. J Neurol Sci 2016;363:182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogata H, Matsuse D, Yamasaki R, et al. A nationwide survey of combined central and peripheral demyelination in Japan. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint Task Force of the EFNS and the PNS. European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society guideline on management of multifocal motor neuropathy: report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society, first revision. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2010;15:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedetti L, Briani C, Franciotta D, et al. Rituximab in patients with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: a report of 13 cases and review of the literature. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:306–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:676–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]