Abstract

Physician burnout is gaining increased attention in medicine and neurology and often relates to hours worked and insufficient time. One component of this is administrative burden, which relates to regulatory requirements and electronic health record tasks but may also involve increased time spent processing emails. Research in academic medical centers demonstrates that physicians face increasing inbox sizes related to mass distribution emails from various sources on top of emails required for patient care, research, and teaching. This commentary highlights the contribution of administrative tasks to physician burnout, research to date on email in medical contexts, and corporate strategies for reducing email burden that are applicable to neurology clinical practice. Increased productivity and decreased stress can be achieved by limiting the amount one accesses email, managing inbox size, and utilizing good email etiquette. Department and practice physician leaders have roles in decreasing email volume and modeling good practice.

Increasing publications highlight the problem of physician burnout overall and in neurology.1,2 Reasons for neurologist burnout are complex and varied, but relate in part to hours worked and having too much work for the available time.1,2

One component of this is administrative burden. A time-motion study of ambulatory specialties identified that physicians spent half their time on electronic health record (EHR) tasks, other deskwork, and other administrative tasks, contrasted with 27% spent on direct clinical care.3 Another study found that physicians spend 24% of their time on administrative duties relating to patient care, with higher amounts of administrative duties associated with lower levels of career satisfaction and higher burnout levels.4 Within neurology, clerical work volume is associated with burnout risk.2 Administrative tasks are associated with high costs and patient care compromises.5

Most administrative burden discussions focus on EHR challenges and regulatory hassles. A potentially overlooked contribution is email. In a 2014 report, an academic physician received 2,035 mass distribution emails: 74% from the medical center, 22% from the department, and 4% from the university.6 Mass distribution physician emails result in wasted time and cost, with an estimated institutional cost of $1,029,419 to $3,088,257 annually using 2009–2010 salary estimates.6 Tracking at another academic practice also revealed that medical center emails comprised the majority of the physician inbox.7

Findings are similar in nonmedical contexts, where in 2015, 20% of email messages delivered to corporate email addresses were spam not caught by filters, including graymail, the term used to describe unwanted newsletters or notifications.8

Physician burden from mass distribution emails is likely increasing. Common mass distribution emails include medical center, university, and departmental communications, invitations to contribute to open access journals and speak at conferences, sales information from medical/laboratory vendors, society membership updates, publication digests, and electronic tables of contents. A 2014–2015 study found that academic physicians received an average of 2.1 spam invitations daily to attend a conference or write/edit for a journal, of which 16% were duplicates and 83% were of minimal relevance to the recipient.9

This mass email burden is superimposed on high email volume occurring in daily practice, where email allows physicians with different schedules to communicate about research, teaching, and practice. Patient email communication is also increasing: in a 2013 survey, 37% of patients with chronic conditions reported contacting their physician by email in the prior 6 months, with frequencies as high as 49% in patients 25–44 years old.10

While research on the effect of email is limited in medicine, one corporate study identified that employees spent 28% of their work week reading and answering email.11 Another found that employees spent 40% of their time handling internal emails adding no value to the business, with 68% of received emails reflecting internal sources.12

In response, businesses are implementing strategies to reduce employee email burden and improve productivity. Medical practices can also adopt these approaches as one strategy for reducing administrative burden.

Limit access

A 2012 survey identified that 60% of professionals, managers, and executives using smartphones for work were connected to work 13.5 or more hours on weekdays and spent approximately 5 hours on weekends scanning email.13 Another 2012 survey found that 68% of people check work email before 8 am, 50% check work email while still in bed, 40% check work email after 10 pm, and 69% will not go to sleep without checking work email.14 A study published by the American Psychological Association (APA) in 2017 reported that 86% of employed Americans constantly or often check their emails, texts, and social media accounts on a typical work day.15

However, research shows that when employees are prevented from accessing email, they focus longer on tasks, multitask less, and demonstrate less physiologic evidence of stress.16 When targeting 3 email log-ins daily, participants handled roughly the same number of emails using approximately 20% less time.17 Limiting email access resulted in significantly lower daily stress and predicted higher well-being on varied outcomes.18 A Forbes article suggests banning email 1 day per week.19

There is also value in reducing email access outside of work hours (table). The APA study found that 81% of employed Americans constantly or often check emails, texts, and social media accounts on nonwork days.15 Stress levels were highest in Americans who check work email constantly on nonwork days, followed by constant checkers in general.15

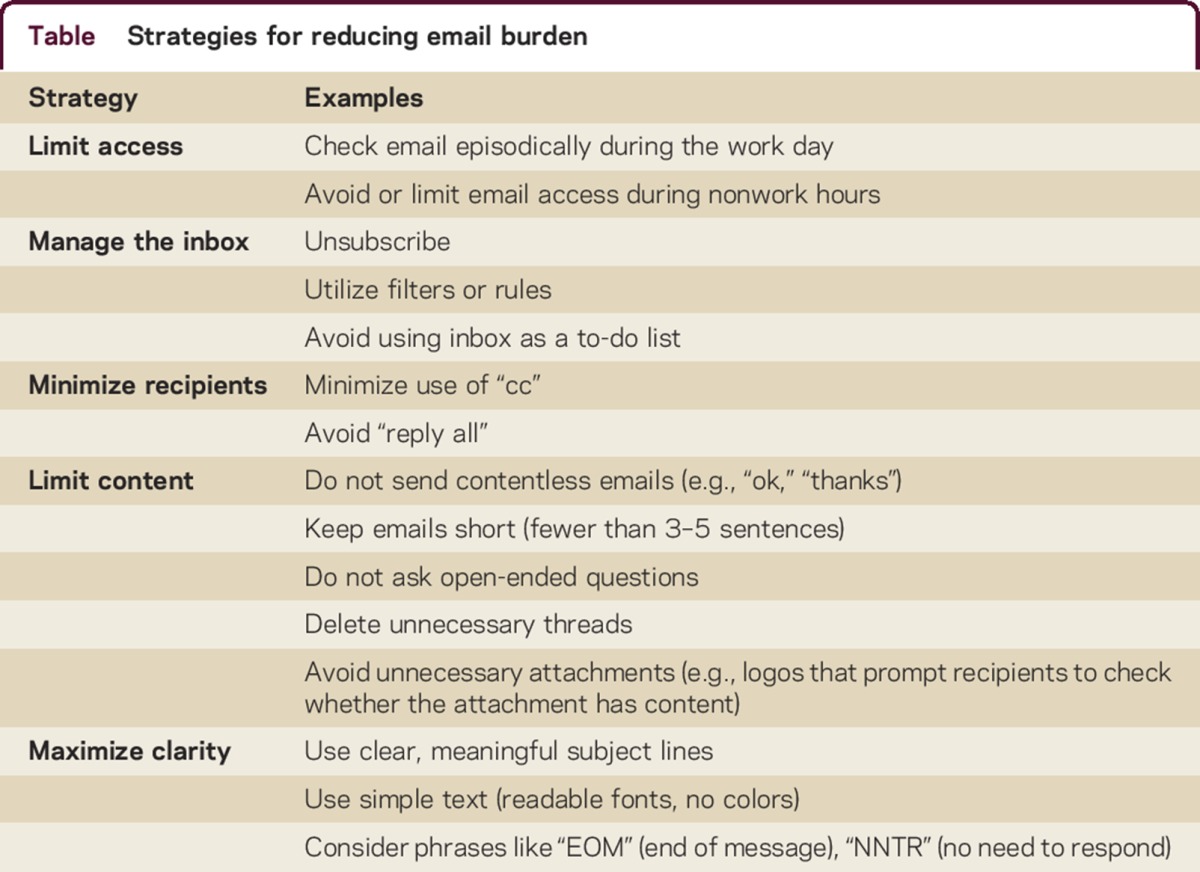

Table.

Strategies for reducing email burden

Companies and countries are taking note. French trade unions negotiated a deal for staff to turn off phones and computers at 6 pm, Volkswagen servers stop routing emails 30 minutes before an employee's end of shift, and Daimler deletes emails sent to vacationing employees who have arranged coverage.20 Atos Origin, an information technology services firm, banned email in 2011, resulting in a 60% reduction in employee email messages per week and improved productivity. The company reported decreased administrative costs, increased operating margin, and increased earnings per share after the policy change.21

Manage the inbox

While limiting email access improves productivity and rest, when logged in, physicians still face daunting inboxes. One mechanism to limit inbox size is unsubscribing (table), though institutional mailing lists are often mandatory and some mass distribution emails do not include unsubscribe options. In addition, research found that unsubscribing from spam conference and journal invitations resulted in a 39% decrease in invitation frequency after 1 month but only a 19% reduction after 1 year.9

A strategy for making inbox use more efficient is personalization of filters or rules. Rules allow the user to divert incoming emails to a specific inbox folder. For example, a rule can automatically collect hospital or university emails in a “university emails” folder. This decreases inbox clutter and highlights higher priority messages. Physicians can efficiently view folder contents once daily, thus keeping abreast of important institutional messages relating to policy announcements, EMR downtime, and safety bulletins without disrupting workflow.

Some authors recommend ceasing the common practice of using one's inbox as a to-do list.22,23 The approach of inbox-as-to-do-list misprioritizes newer emails as more important and results in missing tasks not captured in emails.

Maintain good email etiquette

Despite extensive time spent accessing emails on smartphones, employees describe being more frustrated by companies wasting their time, including through unnecessary emails and poorly planned meetings and projects, than by email volume.13 Email volume and inefficiencies are also highlighted in the Email Charter,24 a private, noncommercial initiative aiming to reduce hours spent on email. Charter concepts are echoed in corporate email practices and also medical education, where a study of surgical residents showed that poorly formatted emails were likely to result in delayed responses and negative perceptions of senders.25

While maintaining good email hygiene depends on colleagues and not just one's own practices, following these standards can result in more efficient emailing and lead to departmental or office culture changes, decreasing email burden for all.

Minimize recipients

No identified research assesses the productivity lost to processing unnecessary emails, but business literature agrees that overuse of “cc” and “reply all” functions multiplies time spent on emails, often without need.23,24

Limit content

Limiting content involves reducing email quantity and length (table). Avoiding contentless emails, such as those merely saying “thank you” or “great,” decreases unnecessary communication.23,24 Strategies to improve efficient handling of emails including limiting length to 3–5 easy-to-read sentences, removing unnecessary threads, and avoiding open-ended questions.22,24 Some even recommend abolishing greetings and signoffs.22 For complex or multiperson discussions that cannot be captured in brief emails, meetings are recommended.

Maximize clarity

Multiple strategies exist for improving email clarity and reducing time spent handling emails (table). Clear subject lines help readers prioritize messages.19,24 Uninformative and missing subject lines are shown to frustrate residents.25 Avoid nonwhite backgrounds and complex fonts.24,25 The Email Charter recommends highlighting when emails are information-only, time-sensitive, or require action.24

Changing culture

Physician leaders have the opportunity to model good email practices to decrease wasted time and money, lessen employee frustrations, and improve efficiency, patient care, and career satisfaction. Leaders can create a culture rejecting 24/7 email expectations, thus improving efficiency in the day and allowing rest at night. Following corporate models, vacationing physicians should be encouraged to obtain coverage and truly disconnect. Physician leaders facilitate effective communication and time management by reducing unnecessary mass emails, clearly marking email priority, and modeling good email etiquette (table).

CONCLUSION

An American College of Physicians position paper calls on stakeholders external to physician practices to reduce administrative burden by assessing whether administrative tasks (1) interfere with provision of timely and appropriate patient care, (2) improve the quality of patient care, (3) have associated financial implications, (4) question physician judgement, and (5) could be accomplished by alternative approaches.5 The report focuses on billing, regulatory, and EHR burdens, but its administrative task taxonomy has relevance for email. Unnecessary emails result in lost time that could be spent on other tasks relating to patient care, research, or home life. This has implications for career satisfaction and burnout, as well as financial implications for practices and universities. Effective combat against constantly increasing inbox sizes requires changes in departmental and practice approaches to mass emails, personal improvements in email etiquette, and employing multiple strategies to limit inbox size.

Footnotes

Editorial, page 462

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.J. Armstrong: Design/conceptualization of manuscript, analysis/interpretation of concepts, drafting of manuscript, revision of manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

M.J. Armstrong is supported by an ARHQ K08 career development award (K08HS24159); receives salary support from the AAN for work as an evidence-based medicine methodology consultant; is on the level of evidence editorial board for Neurology® and related publications; receives publishing royalties for Parkinson's Disease: Improving Patient Care (Oxford University Press, 2014); receives writing/speaker honoraria from Medscape CME; and receives/has received research support from AbbVie, Insightec, NIH, University of Maryland School of Medicine, TBI Endpoints Development Initiative, Parkinson Study Group, Huntington Study Group, and CHDI Foundation. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhou X, Pu J, Zhong X, et al. Burnout, psychological morbidity, job stress, and job satisfaction in Chinese neurologists. Neurology 2017;88:1727–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busis NA, Shanafelt TD, Keran CM, et al. Burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being among US neurologists in 2016. Neurology 2017;88:797–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao SK, Kimball AB, Lehrhoff SR, et al. The impact of administrative burden on academic physicians: results of a hospital-wide physician survey. Acad Med 2017;92:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erickson SM, Rockwern B, Koltov M, McLean RM; Medical Practice and Quality Committee of the American College of Physicians. Putting patients first by reducing administrative tasks in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:659–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul IM, Levi BH. Metastasis of e-mail at an academic medical center. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:290–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geynisman DM. E-mail anonymous: a physician's addiction. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:285–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Email Statistics Report. 2015–2019-Executive Summary. Palo Alto, CA: The Radicati Group, Inc.; 2015. Available at: radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Email-Statistics-Report-2015-2019-Executive-Summary.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grey A, Bolland MJ, Dalbeth N, Gamble G, Sadler L. We read spam a lot: prospective cohort study of unsolicited and unwanted academic invitations. BMJ 2016;355:i5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JL, Choudhry NK, Wu AW, Matlin OS, Brennan TA, Shrank WH. Patient use of email, Facebook, and physician websites to communicate with physicians: a national online survey of retail pharmacy users. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chui M, Manyika J, Bughin J, et al. The social economy: unlocking value and productivity through social technologies. McKinsey Global Institute; 2012. Available at: mckinsey.com/industries/high-tech/our-insights/the-social-economy. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkin N. 40% of Staff time is wasted on reading internal emails. The Guardian; 2012. Available at: theguardian.com/housing-network/2012/dec/17/ban-staff-email-halton-housing-trust. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deal JJ. Always on, never done? Don't blame the smartphone. Center for Creative Leadership; 2013. Available at: ccl.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/AlwaysOn.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Good technology survey reveals Americans working more, but on their own schedule. PR Newswire; 2012. Available at: prnewswire.com/news-releases/good-technology-survey-reveals-americans-working-more-but-on-their-own-schedule-161018305.html. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychological Association. Stress in America: Coping With Change, Part 2 (Technology and Social Media). Stress in America™ Survey. American Psychological Association; 2017. Available at: apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2017/technology-social-media.PDF. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mark GJ, Voida S, Cardello AV. “A pace not dictated by electrons”: an empirical study of work without email. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2012. Austin, TX: Association for Computing Machinery. Available at: ics.uci.edu/∼gmark/Home_page/Research_files/CHI%202012.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kushlev K, Dunn EW. Stop checking email so often. The New York Times; 2015. Available at: nytimes.com/2015/01/11/opinion/sunday/stop-checking-email-so-often.html?_r=1. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kushlev K, Dunn EW. Checking email less frequently reduces stress. Comput Hum Behav 2015;43:220–228. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erwin J. Email overload is costing you billions: here's how to crush it. Forbes; 2014. Available at: forbes.com/sites/groupthink/2014/05/29/email-overload-is-costing-you-billions-heres-how-to-crush-it/#4ba612777ce0. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kjerulf A. 5 Awesome corporate email policies. The Chief Happiness Officer Blog; 2014. Available at: positivesharing.com/2014/11/5-awesome-corporate-email-policies/. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burkus D. Why Atos Origin is striving to be a zero-email company. Forbes; 2016. Available at: forbes.com/sites/davidburkus/2016/07/12/why-atos-origin-is-striving-to-be-a-zero-email-company/#6ded95208d0f. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamblin J. How to email: an etiquette update: brevity is the highest virtue. The Atlantic; 2016. Available at: theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/09/brevity-in-email/501986/. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallo A. Stop email overload. Harvard Business Review; 2012. Available at: hbr.org/2012/02/stop-email-overload-1. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Email Charter [online]. Available at: emailcharter.org/. Accessed June 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Resendes S, Ramanan T, Park A, Petrisor B, Bhandari M. Send it: study of e-mail etiquette and notions from doctors in training. J Surg Educ 2012;69:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]