Abstract

In Japan, overwork-related disorders occur among local public employees as well as those in private businesses. However, to date, there are no studies reporting the state of compensation for cerebrovascular/cardiovascular diseases (CCVD) and mental disorders due to overwork or work-related stress among local public employees in Japan over multiple years. This report examined the recent trend of overwork-related CCVD and mental disorders, including the incidence rates of these disorders, among local public employees in Japan from the perspective of compensation for public accidents, using data from the Japanese Government and relevant organizations. Since 2000, compared to CCVD, there has been an overall increase in the number of claims and cases of compensation for mental disorders. Over half of the individuals receiving compensation for mental disorders were either in their 30s or younger. About 47% of cases of mental disorders were compensated due to work-related factors other than long working hours. The incidence rate by job type was highest among “police officials” and “fire department officials” for compensated CCVD and mental disorders cases, respectively. Changes in the trend of overwork-related disorders among local public employees in Japan under a legal foundation should be closely monitored.

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases, Cerebrovascular diseases, Japan, Local public employees, Mental disorders, Overwork, Work stress

Introduction

Cerebrovascular/cardiovascular diseases (CCVD) and mental disorders due to overwork or work-related stress are major occupational and public health issues in East Asian countries1, 2), including Japan3, 4). In Japan, for instance, the number of claims for the “Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance (IACI)” for mental disorders has increased, from 155 in 1999 to 1,586 in the 2016 fiscal year5, 6). According to the National Police Agency of Japan, in 2016, 1,978 people died by suicide due to “work-related issues”, such as exhaustion caused by overwork or workplace bullying7).

Since 1988, with changes in the awareness of overwork-related disorders in the Japanese society, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) of Japan has provided annual brief reports on compensation for CCVD and mental disorders among employees of private companies6). Recently, our peer report presented the details of the state of occupational CCVD and mental disorders among employees in Japan over the past five years4).

In Japan, compensation for job-related death/injury/impairment of private company employees is paid by the IACI, while those of local public employees is administered by the “Fund for Local Government Employees’ Accident Compensation”8). However, while only two brief annual reports on the compensation of overwork-related disorders among local public employees have been published8), there has been no study examining the state of overwork-related disorders among public employees over multiple years, including the incidence rates of these disorders. In Japan, it has been suggested that work-related CCVD and mental disorders have occurred among local public employees, such as teachers in public schools, and police and fire department officials, and have been a serious occupational health issue5), although the total number of local public employees has been relatively small as compared to that of employees of private companies. Providing an overview of the state of overwork-related disorders among local public employees in Japan would contribute to the development of public employee-specific preventive measures against these conditions.

In the present paper, we examined recent trends in overwork-related CCVD and mental disorders among local public employees in Japan from the perspective of compensation for public accidents. To provide an overview of the state of overwork-related disorders, we used the following information: (1) brief annual reports on the compensation of overwork-related disorders among local public employees for fiscal years 2013 to 2015, published by the Fund in 2016 and 20178); (2) the 2016 White Paper on overwork-related disorders, published by the MHLW in 20165); and (3) reports on the total number of local public employees by job type for the fiscal years 2013 to 2015 to calculate the incidence rate of compensated cases, published annually by the Japan Local Government Employee Safety and Health Association in 2015, 2016, and 20179). No information regarding the state of overwork-related disorders among local public employees by sex and diagnosis has been made available by the Government of Japan or relevant governmental organizations. In this study, we examined overwork-related CCVD and mental disorders among local public employees based on relevant factors, including year of claim and compensation, age, job type, working hours, and work events. We reviewed the annual trend of claims and cases of compensation for the fiscal years 1999 to 2015, while we analyzed the state of overwork-related disorders by age, job type, working hours, and work events for the fiscal years 2013 to 2015.

Ethical approval for this study was not sought because only annual summary values for each factor were used in the study, which were provided by the Government of Japan or relevant governmental institutions and did not include any personally identifiable information.

Annual trends

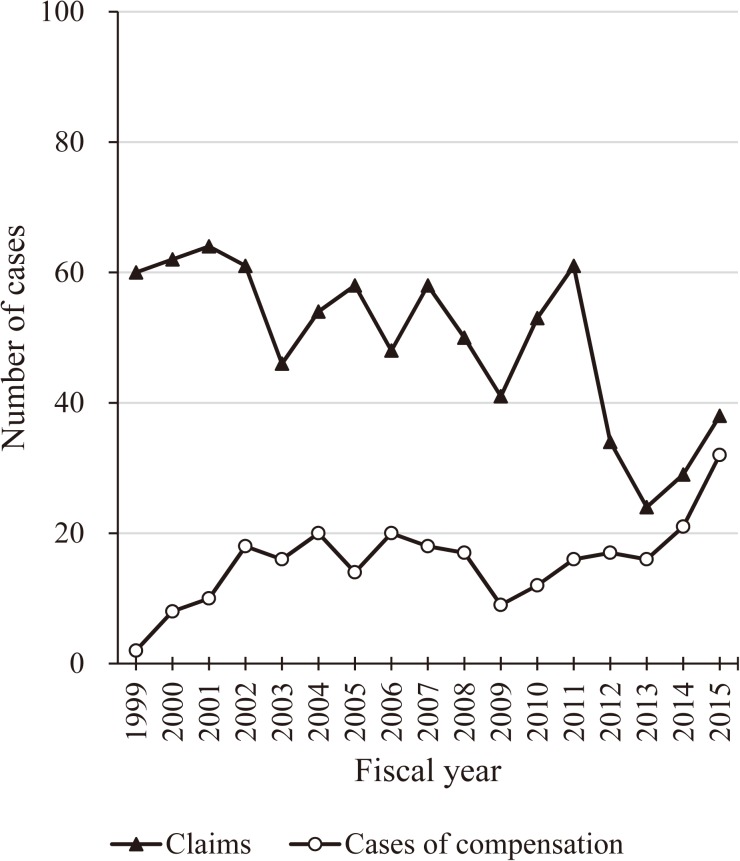

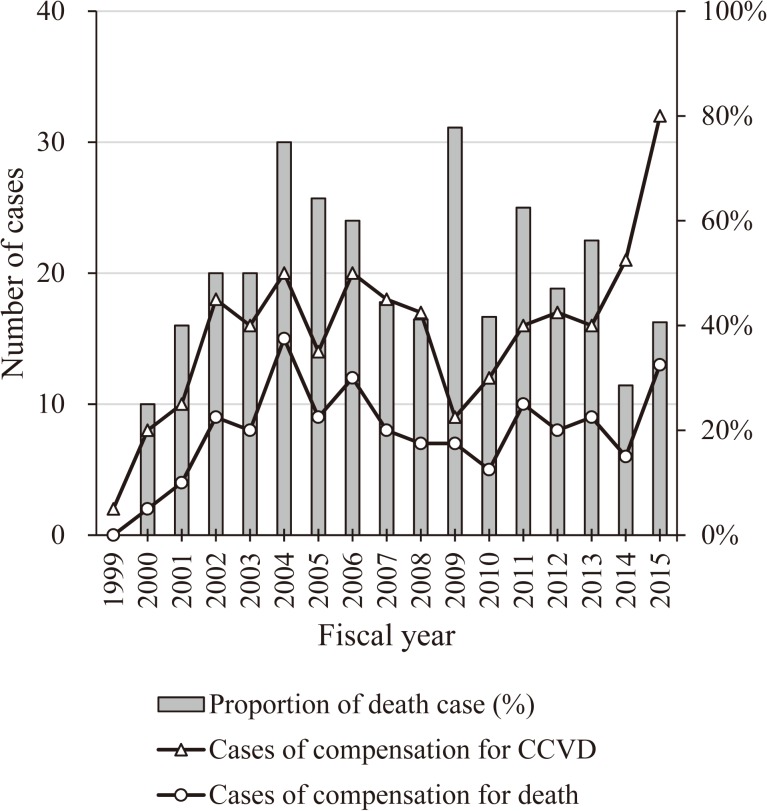

Figures 1-(a) and 2-(a) show the trend of claims and cases of compensation for CCVD among local public employees in Japan between the fiscal years 1999 and 20155, 8). Until 2014, 20 or fewer cases per year of CCVD received compensation. Recently, the number of uncompensated cases has decreased. In 2015, there were 38 claims for compensation, of which 32 received compensation. Of these, 13 cases (40.6%) died due to CCVD.

Fig. 1-(a).

Number of claims and cases of compensation for cerebrovascular/cardiovascular disease, FY1999–FY2015.

Fig. 2-(a).

Proportion of deaths among cases of compensation for cerebrovascular/cardiovascular disease (CCVD), FY1999–FY2015.

In 2001, the MHLW relaxed the definition of heavy workloads in the amendment of certification criteria of the IACI for compensation for CCVD. In the same year, the certification criteria of the Fund for compensation for CCVD were also amended. These background factors may have contributed to the annual trend of compensation for CCVD among local public employees since 2002. Furthermore, as argued in our recent report4), in June 2014, the National Diet of Japan passed the “Act on Promotion of Preventive Measures against Karoshi and Other Overwork-Related Health Disorders.” The Act aimed to clarify the responsibilities of the state in the promotion of preventive measures against overwork-related disorders and to contribute to realizing a society where people can work healthily and actively with an adequate work–life balance. Under the Act, in July 2015, the Cabinet of Japan adopted the “Principles of Preventive Measures against Overwork-Related Disorders” to provide a practical framework for preventive measures against overwork-related disorders. Prior to this, in response to action from relevant individuals and organizations, including family members of those who died due to overwork-related disorders, lawyers, and personnel of non-profit organizations, with more than 500,000 signatories among the general public, a cross-party group of lawmakers of the Diet was established to call for a legislation regarding the prevention of overwork-related disorders. These background factors may have contributed to the increase in the number of claims and cases of compensation for overwork-related disorders among local public employees after the fiscal year 2014.

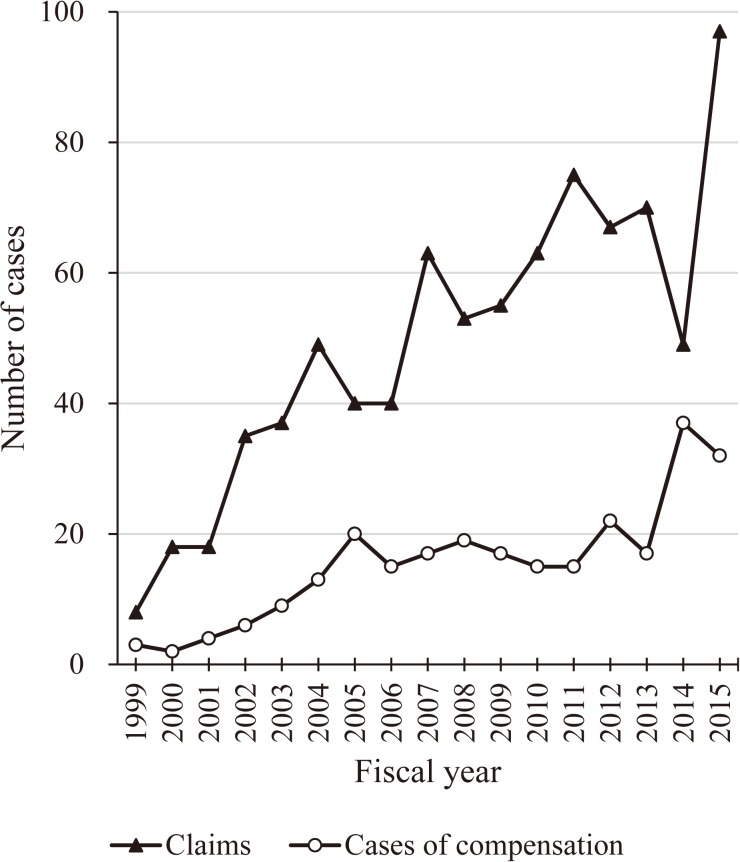

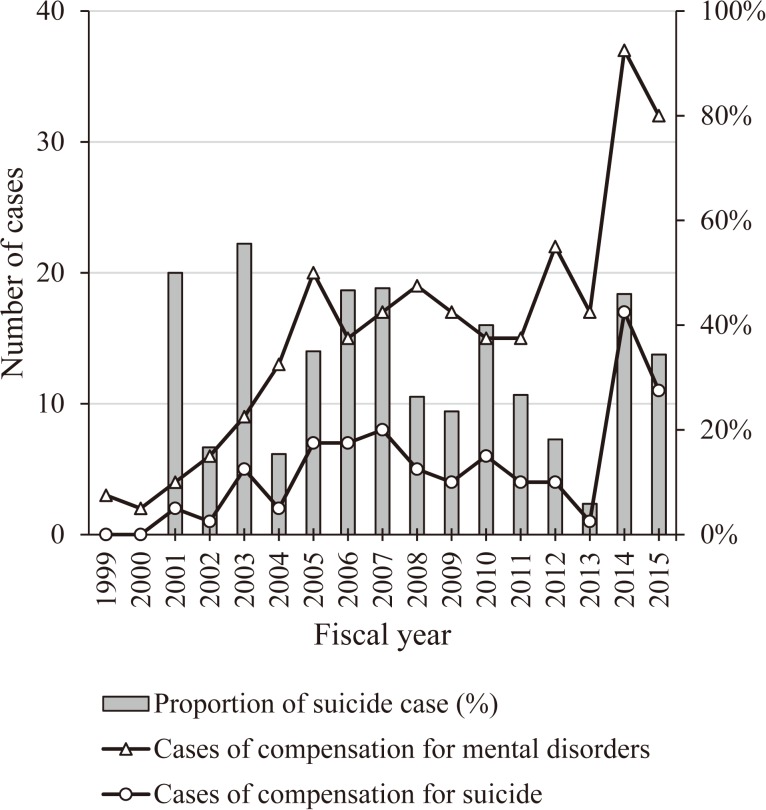

Figures 1-(b) and 2-(b) present the trend of claims and cases of compensation for mental disorders among local public employees in Japan between the fiscal years 1999 and 20155, 8). Since 2000, both the number of claims and of cases of compensation have increased, possibly due to the implementation of guidelines for compensation for mental disorders for local public employees by the Fund in 19998). In 2015, 97 claims were submitted, and 32 cases received compensation. Of these, 11 (34.4%) represented suicide cases.

Fig. 1-(b).

Number of claims and cases of compensation for mental disorders, FY1999–FY2015.

Fig. 2-(b).

Proportion of suicides among cases of compensation for mental disorders, FY1999–FY2015.

In the fiscal year 2015, the number of claims for mental disorders increased sharply from 49 in 2014 to 97 in 2015. This may be due to the amendment of the certification criteria of the Fund in 2012. It is important to examine whether this trend will persist.

In the fiscal year 2015 (i.e., the first full fiscal year after the “Act on Promotion of Preventive Measures against Karoshi and Other Overwork-Related Health Disorders” was enacted in Japan in November 201410)), the number of claims for compensation for both CCVD and mental disorders among local public employees increased relative to the preceding year (Fig. 1-(a) and Fig. 1-(b)), particularly for mental disorders. This trend may be due to increased awareness of overwork-related disorders and the compensation system of the Fund for CCVD and mental disorders, following the enactment of legislation and media reports in Japan on overwork-related disorders.

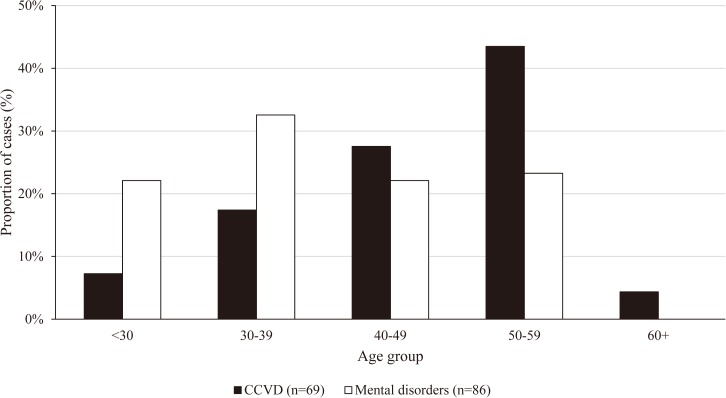

Age

Figure 3 shows the age distribution of cases of compensation for CCVD and mental disorders among local public employees in Japan between the fiscal years 2013 and 20158). Compensation occurred more frequently among individuals aged 50 to 59 yr (43.5%), followed by those aged 40 to 49 yr. Compensation for mental disorders occurred more frequently among young employees, particularly those aged 30 to 39 yr (32.6%).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of cases of compensation for cerebrovascular/cardiovascular disease and mental disorders by age group, FY 2013–FY2015.

As shown in Fig. 3, over half of the individuals receiving compensation for mental disorders were in their 30s or younger. These findings are consistent with those of employees in private companies receiving compensation4, 5, 6), suggesting the importance of promoting mental health-related support for young employees both in the public and non-public sectors, as well as increasing the awareness of working conditions among young people.

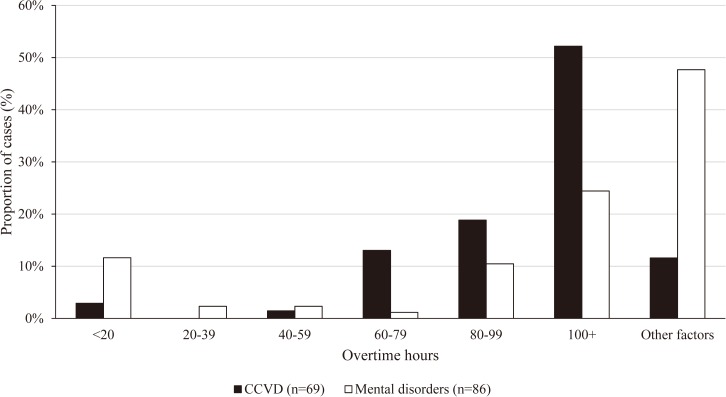

Working hours and work events

Figure 4 shows the distribution of overtime hours among local public employees compensated by the Fund during the fiscal years 2013 and 20158). Notably, in 71.0% of cases of compensation for CCVD, overtime hours exceeded 80 h per month prior to the onset of CCVD. Conversely, 47.7% of cases of mental disorders (and possibly, about 10% of cases working less than 20 h of overtime) were compensated due to work-related factors other than long working hours, including exposure to extremely stressful work events, such as severe sexual harassment/violence or accidents/natural disasters.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of cases of compensation for cerebrovascular/cardiovascular disease and mental disorders by overtime hours, FY2013–FY2015.

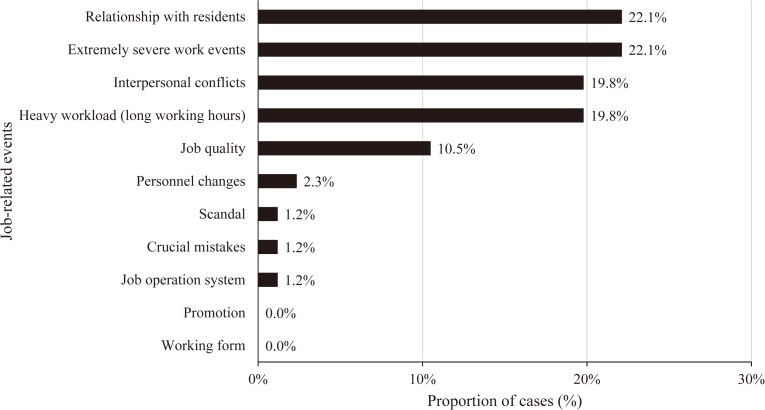

Figure 5 depicts the distribution of cases of compensation for mental disorders by work event during the fiscal years 2013 and 20158). During the three-yr period, the most frequently recognized work events (22.1%) were “relationship with residents” and “extremely severe work events,” followed by “interpersonal conflicts” and “heavy workload (long working hours)”. “Relationship with residents” may be considered a local public employee-specific work event for public servants, as well as public services after “extremely severe work events,” including natural disasters, such as the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima Nuclear Power Accident which occurred in March 201111).

Fig. 5.

Distribution of cases of compensation for mental disorders by job-related events, FY2013–FY2015.

Job type

Table 1 depicts the distribution of cases of compensation for CCVD and mental disorders by job type between the fiscal years 2013 and 20158). Regardless of the type of disorder (i.e., CCVD or mental disorders), the highest number of cases of compensation were observed among “other local public officials” (including local government officials engaged in document work as well as physicians and nurses in local public hospitals, caregivers for the elderly, and public health nurses), particularly for mental disorders. Furthermore, 30.4% of cases of compensation for CCVD involved “teachers/workers in schools offering compulsory education,” followed by “police officials.” The largest number of employees who obtained compensation for mental disorders included “other local public officials” and “fire department officials,” followed by “teachers/workers in schools offering non-compulsory education.”

Table 1. The number and incidence rate of cases of compensation for cerebrovascular/cardiovascular disease and mental disorders by job type.

| Job type | Cerebrovascular/cardiovascular disease | Mental disorders | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of employeesa) | No. of casesb) | Incidence rate (per 1 million) | No. of casesb) | Incidence rate (per 1 million) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Teachers/workers in compulsory education schools | 2,059,224 | 25.0% | 21 | 30.4% | 10.2 | 8 | 9.3% | 3.9 | ||

| Teachers/workers in non-compulsory education schools | 1,035,172 | 12.6% | 6 | 8.7% | 5.8 | 9 | 10.5% | 8.7 | ||

| Police officials | 853,838 | 10.4% | 16 | 23.2% | 18.7 | 8 | 9.3% | 9.4 | ||

| Fire department officials | 477,708 | 5.8% | 3 | 4.3% | 6.3 | 11 | 12.8% | 23.0 | ||

| Sanitation department officials | 145,426 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.0 | ||

| Other local public officials | 3,672,300 | 44.5% | 23 | 33.3% | 6.3 | 50 | 58.1% | 13.6 | ||

| Total | 8,243,668 | 100% | 69 | 100% | 8.4 | 86 | 100% | 10.4 | ||

a) Data from Japan Local Government Employee Safety and Health Association. This column does not include the number of part-time employees.

b) Total number of cases receiving compensation between the fiscal years 2013 and 2015. This column includes claims for compensation brought before the fiscal year 2013. These columns do not include the number of part-time employees.

Conversely, among cases of compensation for CCVD, the highest incidence rate (i.e., the number of cases of compensation for CCVD and mental disorders per 1 million local public employees) by job type was found among “police officials” (18.7/million), followed by “teachers/workers in schools offering compulsory education.” Among cases of compensation for mental disorders, the highest incidence rate was observed among “fire department officials” (23.0/million), followed by “other local public officials”, suggesting that “other local public officials” may not necessarily receive compensation more frequently than those in other job types, taking the total number of local public employees in each job type as the denominator9).

The highest incidence of cases of compensation per 1 million local public employees by job type was found among “police officials” for CCVD and among “fire department officials” for mental disorders. These findings suggest that job-specific preventive measures against overwork-related disorders are needed.

Conclusions

We analyzed the recent trends in compensation for CCVD and mental disorders due to overwork or work stress among local public employees in Japan. Compared to studies on CCVD and mental disorders among employees at private companies4), there were limited data regarding overwork-related disorders among local public employees in Japan. While information regarding sex ratio and diagnosis among compensated local public employees were not included in the present paper due to the lack of the relevant data, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to show the state of overwork-related disorders among local public employees from the perspective of compensation for public accidents over multiple years. On the other hand, no information regarding the state of overwork-related disorders among public employees by area has been made available. In Japan, the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred on March 11, 2011. Thus, there might be a substantial difference in the state of overwork-related disorders among public employees in the disaster area compared to those in other areas in Japan during the study period.

Consistent with the recent IACI trends in claim and compensation, the number of claims and compensation for mental disorders among local public employees has generally increased. The distribution of age and working hours/work events among cases of compensation were also comparable to those among employees of private businesses. While there may be public employee-specific or job type-specific factors, as observed among employees of private businesses, long working hours and interpersonal conflicts were also primary reasons for compensation among local public employees.

There has been a recent increase in the number of media reports in Japan regarding cases of compensation among local public employees, as well as among employees of private companies. Guidelines for compensation of overwork-related disorders for employees of private companies and local public employees have been also established. In 2014, the enactment of the act was widely reported by the Japanese media. Furthermore, under the act, the Cabinet of Japan adopted the principles in 2015, to provide a practical framework and immediate objectives to prevent overwork-related disorders. These factors may contribute to the recent trend in the compensation of local public employees in Japan.

The objectives of the principles include the promotion of awareness of overwork-related issues among public employees and the setting up of a counselling service system for public employees. Although preventive measures against overwork-related disorders which were regulated in the principles mainly focus on employees of private companies, our findings suggest that it is important to develop preventive measures for public employees, including police officers and fire department officials in whom the incidence rate of cases of compensation was high. Changes in the trends of overwork-related disorders among public employees in Japan in the context of recent developments in the law should be evaluated so that other countries can benefit from the experience.

Disclaimer

The content of this report reflects the views of the authors and does not necessarily that of the Government of Japan. The translation of the names of proper nouns from Japanese into the English language was made by the authors and is not an official translation by the Government of Japan.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP17K10348.

References

- 1.Cheng Y, Park J, Kim Y, Kawakami N (2012) The recognition of occupational diseases attributed to heavy workloads: experiences in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 85, 791–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee J, Kim I, Roh S (2016) Descriptive study of claims for occupational mental disorders or suicide. Ann Occup Environ Med 28, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwasaki K, Takahashi M, Nakata A (2006) Health problems due to long working hours in Japan: working hours, workers’ compensation (Karoshi), and preventive measures. Ind Health 44, 537–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamauchi T, Yoshikawa T, Takamoto M, Sasaki T, Matsumoto S, Kayashima K, Takeshima T, Takahashi M (2017) Overwork-related disorders in Japan: recent trends and development of a national policy to promote preventive measures. Ind Health 55, 293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Government of Japan 2016. White paper on preventive measures against overwork-related disorders (Karoshi tou boushi taisaku hakusyo) [in Japanese]. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/wp/hakusyo/karoushi/16/index.html. Accessed July 19, 2017.

- 6.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Government of Japan Heisei 28 nendo karoshi-tou no rousai hosyou jyoukyou wo kouhyou. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/0000168672.html. Accessed July 15, 2017.

- 7.National Police Agency, Government of Japan Toukei [in Japanese]. https://www.npa.go.jp/publications/statistics/index.html. Accessed July 15, 2017.

- 8.Fund for Local Government Employees’ Accident Compensation Fund for Local Government Employees’ Accident Compensation. http://www.chikousai.jp/. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 9.Japan Local Government Employee Safety and Health Association Koumu saigai no genkyou. http://www.jalsha.or.jp/tyosa/result2. Accessed July 15, 2017.

- 10.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Government of Japan Karoshi tou boushi taisaku ni kansuru hourei [in Japanese]. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000053525.html. Accessed July 15, 2017.

- 11.Konno S, Hozawa A, Munakata M (2013) Blood pressure among public employees after the Great East Japan Earthquake: the Watari study. Am J Hypertens 26, 1059–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]