Abstract

Previous research has shown an association between child maltreatment (sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect or witnessing interparental violence) and adolescent sexual risk behaviors. The mechanisms explaining this association are not well understood but attachment theory could provide further insight into them. This study examined the relationships between child maltreatment and sexual risk behaviors and investigated anxious and avoidant attachment as mediators. The sample comprised 1,900 sexually active adolescents (13 to 17 years old; 60.8% girls) attending Quebec high schools. The results of path analyses indicated that neglect was associated with a higher number of sexual partners, casual sexual behavior, and being younger at first intercourse. Anxious attachment mediated the relation between neglect and number of sexual partners, whereas avoidant attachment explained the relation between neglect and number of sexual partners, casual sexual behavior, and age at first intercourse (for boys only). Sexual abuse was directly associated with all three sexual risk behaviors. Neither anxious attachment nor avoidant attachment mediated these associations. Youth with a history of neglect and sexual abuse represent a vulnerable population that is likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors. Interventions designed to induce a positive change in attachment security may reduce sexual risk behaviors among victims of neglect.

Keywords: abuse, attachment, adolescent sexuality, gender differences

Sexual risk behaviors (SRBs) represent a major public health concern. There is an increasing level of SRBs during adolescence, followed by a decrease in young adulthood (Fergus, Zimmerman, & Caldwell, 2007). SRBs place adolescents at heightened risk for teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (Boislard, van de Bongardt, & Blais, 2016). Adolescents with a history of child maltreatment (CM) are more likely than their nonvictimized peers to engage in SRBs. Indeed, a meta-analysis indicated a consistent association across studies between sexual abuse and a wide range of SRBs during adolescence, including a greater number of sexual partners and younger age at first intercourse (Senn, Carey, & Vanable, 2008). An increasing body of studies has also demonstrated an association between sexual abuse and sexual contacts with strangers (i.e., casual sexual behaviors) (Olley, 2008). Casual sexual behaviors are closely related to SRBs, such as having multiple sexual partners (Scott et al., 2011) and a higher risk for sexually transmitted infections (Boislard et al., 2016).

A more limited number of studies explored the association between other forms of CM and SRBs, with findings pointing in the same direction. Physical abuse and neglect were also associated with a greater number of sexual partners, casual sexual behaviors, and a younger age at first intercourse (Negriff, Schneiderman, & Trickett, 2015; Senn & Carey, 2010; Wilson & Widom, 2008; Wilson, Woods, Emerson, & Donenberg, 2012). Witnessing interparental violence was also associated with SRBs during adolescence (Elliott, Avery, Fishman, & Hoshiko, 2002) and adulthood (Bair-Merritt, Blackstone, & Feudtner, 2006). Wilson et al. (2012) did not find an association between witnessing interparental violence and SRBs in their sample of African-American girls. However, their sample originated from a clinical and socially disadvantaged population and results cannot be generalized for the population as a whole.

The current literature on the relation between CM and SRBs is limited by two methodological factors. First, studies have often focused on one or two particular forms of CM (e.g., sexual abuse, physical abuse) (Littleton, Radecki Breitkopf, & Berenson, 2007). However, CM rarely occurs in isolation (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007). Thus, examining one or two forms of CM does not provide information on the total effect of exposure to cumulative abuse but also leads to an overestimation of the consequences of a single form of CM, as demonstrated by Turner, Finkelhor, and Ormrod (2010). Second, even if the link between CM and SRBs is increasingly recognized, information is limited on the potential pathways through which CM could influence SRBs. Identifying those pathways is critical to understanding the mechanisms by which exposure to CM fosters SRBs and determining who is at greatest risk. In addition, documentation of the potential mechanisms involved could inform treatment and preventive efforts.

One of the earliest impacts of CM is on the child’s attachment system functioning and internal representations of self and others (Briere, 2002). It has been reported that attachment insecurity, characterized by high levels of avoidance or anxiety, is a pathway between CM and a wide range of outcomes, such as risk behaviors (e.g., drug and alcohol use) (Oshri, Sutton, Clay-Warner, & Miller, 2015) and psychological (Muller, Thornback, & Bedi, 2012) and relationship functioning (Owen, Quirk, & Manthos, 2011). Although anxious and avoidant attachment have been proposed as possible pathways between CM and SRBs (Briere, 2002; Cicchetti & Toth, 2005), they have not been empirically investigated with mediation models.

Given the limitations noted, the current study investigated the associations between forms of CM and adolescent SRBs. Four forms of CM (sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect, and witnessing interparental violence) and three SRBs (number of sexual partners, age at first intercourse, and casual sexual behavior) were examined. In addition, anxious and avoidant attachment were examined as mediators of the associations between forms of CM and SRBs.

Attachment Theory

Initially defined by Bowlby (1982), attachment theory is based on the innate tendency to create emotional bonds with others. Early experiences with significant adult figures are internalized into mental representations of self and others called internal working models. When significant adult figures are attentive and responsive, children tend to be comfortable being emotionally close with others and relying on attachment figures, which results in attachment security (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Secure individuals have positive representations of self and others, higher self-esteem and good abilities to form and maintain intimate relationships. Conversely, when important adult figures are rejectful or unreliable, children tend to develop negative internal working models (negative representations of self and others) and become insecurely attached. Insecure individuals, in contrast to secure individuals, have a high level of avoidance or anxiety, or a high level of both (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). A high level of avoidance is characterized by negative representations of others with expectations that the parent will be unavailable, unresponsive, or emotionally distant, resulting in discomfort with intimacy and interdependence. A high level of anxiety is characterized by negative representations of self and fear of rejection, resulting in a compulsive need for closeness, intimacy, and reassurance (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

From a theoretical perspective, victims of CM are likely to develop negative representations of self and conclude that they are intrinsically unacceptable and deserving of maltreatment (Briere, 2002). In addition, maltreated children are more likely to develop negative representations of others and view them as being rejectful and unavailable. The association between CM and high level of attachment insecurity (both avoidance and anxiety) has been widely supported in previous decades (Baer & Martinez, 2006; Cicchetti & Toth, 2005; Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2010). Depending on the nature of the CM experienced, children may develop anxious or avoidant attachment. For example, a neglected child may develop an anxious attachment when caregiver does not respond consistently to his or her needs. Furthermore, a neglected child may also develop an avoidant attachment when a caregiver is rejectful and not comfortable with physical contact (Mikulincer, Shaver, & Pereg, 2003). Representations of self and others internalized during childhood (i.e., internal working models) are described as relatively stable across the life span (Waters, Merrick, Treboux, Crowell, & Albersheim, 2000). In a longitudinal study assessing attachment security during infancy and in young adulthood, 72% of participants received the same secure or insecure classification 20 years later (Waters et al., 2000). However, this means that the classification of more than one out of four individuals changed. Thus, the stability of attachment security depends on the consistency not only of caregiver behavior but also of later interactions – positive or negative – with other significant individuals in the environment.

Briere (2002) and Cicchetti and Toth (2005) propose attachment theory as a relevant framework to explain how CM may lead to various consequences such as SRBs and encouraged further studies on the topic. Although attachment security and sexuality are regulated by different systems, they influence each other (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). For example, to avoid disapproval and rejection, anxiously attached individuals may consent to SRBs that they do not particularly want (Davis, Shaver, & Vernon, 2004). Similarly, avoidantly attached individuals may have multiple sexual partners and sexual contacts with strangers (casual sexual behaviors) to inhibit the development of deep emotional attachment, which is the function of intimacy avoidance (Davis et al., 2004; Fraley & Shaver, 2000).

A growing body of research showing an association between insecure attachment and SRBs reinforced the hypothesis of attachment as a potential mechanism. However, findings are currently mixed and unclear, mainly because gender differences have been left out in most studies (Cooper et al., 2006). In regard to attachment anxiety, a high level has been linked with a younger age at first intercourse among girls (Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Gentzler & Kerns, 2004); for boys, attachment anxiety is linked with an older age at first intercourse (Gentzler & Kerns, 2004). Anxious attachment is not associated with the number of sexual partners in Lemelin, Lussier, Sabourin, Brassard, and Naud (2014), while Gentzler and Kerns (2004) found that anxious attachment is associated with fewer sexual partners for boys but not for girls. Furthermore, studies of college students have concluded that no relationship exists between anxious attachment and a greater number of casual sexual behaviors (Garneau, Olmstead, Pasley, & Fincham, 2013; Gentzler & Kerns, 2004).

In regard to attachment avoidance, Tracy, Shaver, Albino, and Cooper (2003) showed that a high level of attachment avoidance was associated with an older age at first intercourse, while Lemelin et al. (2014) reported an association with a younger age at first intercourse. As these studies use relatively comparable samples, the mixed results may arise from the failure to consider gender differences. There is more agreement among studies showing that avoidantly attached individuals engage in more casual sexual behaviors (Garneau et al., 2013; Gentzler & Kerns, 2004; Paul, McManus, & Hayes, 2000) and have a greater number of sexual partners (Lemelin et al., 2014; Szielasko, Symons, & Price, 2013). Costa and Brody (2011) did not find that avoidant or anxious attachment was associated with number of sexual partners. However, their sample was small (N = 70) and statistical power may be a concern. Thus, replication studies are needed to better understand the relationship between attachment insecurity and SRBs in adolescent populations.

Despite growing evidence that attachment is a promising mechanism explaining the association between CM and SRBs, empirical studies with mediation analyses are indeed lacking. The study conducted by Oshri et al. (2015) is an exception. They examined the relationships between various forms of CM and condom use and investigated whether anxious and avoidant attachment mediated the relationships. They did not find support for attachment insecurity as a mechanism to explain the association between various forms of CM and condom use among young adults (19 to 32 years old). However, condom use was measured only in the context of sexual contacts with someone who was not a romantic partner (i.e., casual sexual behaviors). This measure does not reflect condom usage in more general situations, given that sexual contacts with casual partners represent only a small portion of sexual experiences during adolescence.

The Present Study

The goal of the present study was to examine the potential mediating role of attachment insecurity in explaining associations between forms of CM (i.e., sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect, and witnessing interparental violence) and SRBs in a large representative sample of high school adolescents (see Figure 1 for the hypothesized model). We specifically tested the role of avoidant attachment and anxious attachment. For SRBs, the number of sexual partners and age at first intercourse were selected because they are commonly used to operationalize SRBs among youth (Boislard et al., 2016) and were investigated as separate outcomes. We also examined casual sexual behavior (i.e., sexual contacts with strangers), which reflects contemporary changes in sexual relationships (Boislard et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model depicting attachment (i.e., anxious and avoidant) as mediator of the relationship between child maltreatment (Time 1 = baseline) and sexual risk behaviors (Time 2 = 6 months follow-up). Casual sexual behavior represents sexual contacts with a stranger. For figure clarity, control variables (i.e., family structure and mother’s education), direct effects of child maltreatment on sexual risk behaviors, and non-significant effects (hypothesized) are not depicted. Moderation by gender for paths between attachment and sexual risk behaviors was tested.

aNeglect was measured at Time 2 but refers to childhood experiences.

bThe path between anxious attachment and age at first intercourse is significant only for girls (hypothesized).

First, we hypothesized that all four forms of CM (sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect, and witnessing interparental violence) would be directly associated with a higher number of sexual partners, casual sexual behavior, and younger age at first intercourse (hypothesis 1). Next, we hypothesized that all four forms of CM would be associated with avoidant attachment, which in turn would lead to a higher number of sexual partners (hypothesis 2) (Lemelin et al., 2014; Szielasko et al., 2013). Then, we hypothesized that all four forms of CM would be associated with anxious attachment, which in turn would lead to a younger age at first intercourse for girls (hypothesis 3). We also hypothesized that all four forms of CM would be associated with avoidant attachment, which in turn would lead to casual sexual behavior (hypothesis 4) (Garneau et al., 2013).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data for this study were obtained from the Quebec Youths’ Romantic Relationships survey. The sample included 8,194 adolescents enrolled in grades 10 through 12 in the province of Quebec (Canada). Adolescents were recruited from a one-stage stratified cluster sample of high schools. Schools were randomly selected from an eligible pool from the Quebec Minister of Education, Recreation and Sports. The overall response rate, defined as the ratio of the number of students who decided to participate and the number of solicited students, was 99%. Adolescents completed self-administered questionnaires in school in the fall of 2011 (Time 1) and the spring of 2012 (Time 2). The response rate at Time 2 was 70.1%. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The research ethic boards at the Université du Québec à Montréal approved this project (2011-S-591906). Further publications using this database are available at http://martinehebert.uqam.ca/fr/.

To obtain a representative sample of Quebec adolescents attending public high schools, schools were first classified into eight strata according to the geographical area, school status (public or private), teaching language (French or English), and socioeconomic deprivation index. Participants were given a sample weight in all analyses to correct biases related to the nonproportionality of the schools in the sample compared to the target population. The weight was defined as the inverse of the probability of selecting the given grade in the respondent’s stratum in the sample multiplied by the probability of selecting the same grade in the same stratum in the population (N weighted = 6,540). The analytical sample was restricted to sexually active adolescents (i.e., who had already had a consensual sexual relationship with oral, vaginal, or anal penetration) 17 years of age or younger. Participants who had never had a romantic relationship (N = 40) were excluded due to their ineligibility to complete the attachment questionnaire in the survey (i.e., the attachment measure used in this survey is designed for participants who have already had a romantic relationship). The final sample comprised 1,900 high school adolescents aged between 13 and 17 years (Mage = 15.6, SD = .09), including 1,158 girls (60.9%) and 742 boys (39.1%). A total of 467 (24.6%) participants were in grade 9,640 (33.7%) were in grade 10, and 757 (39.9%) were in grade 11. The remaining 1.8% of the adolescents reported being on an individualized path for learning. Most of the respondents (79.3%) were born in Canada to parents who were both born in Canada. Furthermore, 85.2% of the participants identified as Quebecois or Canadian. A minority (3.5%) of the respondents identified as Latino American, whereas 3.0% identified as Western European, and 2.0% identified as Caribbean/West Indian. The remaining 6.3% of respondents reported identifying with other ethnic groups. The majority of adolescents spoke French at home (91.9%). More than half of the adolescents (54.9%) reported living with their family of origin, and 45.1% of them reported living with their separated parents or others. Approximately half of the adolescents had a mother (65.8%) and a father (46.5%) with a post-high school degree, most of whom were currently working (83.4% and 85.0%, respectively). With regard to sexual orientation, 83.5% identified as heterosexual, whereas the remaining participants said they were bisexual (12.7%), homosexual (2.0%), or questioning (1.8%).

Measures

Childhood maltreatment

CM was assessed at Time 1 (otherwise noted). Lifetime measures were used in accordance with recommendations proposed in a recent literature review (Scott-Storey, 2011). Two items assessing sexual abuse were adapted from Quebec and American surveys (Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990; Tourigny, Hébert, Joly, Cyr, & Baril, 2008). The first item assessed unwanted sexual touching: “Have you ever been touched sexually when you did not want to, or have you ever been manipulated, blackmailed, or physically forced to touch sexually?” The second assessed unwanted sexual intercourse: “Excluding the sexual touching mentioned in the previous item, has anyone ever used manipulation, blackmail, or physical force, to force or obligate you to have sex (including all sexual activities involving oral, vaginal, or anal penetration)?” Participants indicated whether they had experienced these two sexual contacts with four different perpetrators (a member of your immediate or extended family, a sports trainer, a person outside your family that you knew [other than a boyfriend or girlfriend], and a stranger) (1 = Yes, 0 = No). Adolescents who reported unwanted sexual touching or unwanted sexual intercourse were coded as having experienced sexual abuse (1 = Yes, 0 = No).

Physical abuse was assessed with one item adapted from the Childhood Maltreatment Interview Schedule – Short Form (Briere, 1992) and the Early Trauma Inventory – Short Form (Bremner, Bolus, & Mayer, 2007): “Have you ever been physically hit by amember of your family?” (1 = Yes, 0 = No).

Neglect was assessed using four items adapted from The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Hahm, Lee, Ozonoff, & Wert, 2010) and the Early Trauma Inventory – Short Form (Bremner, Bolus, & Mayer, 2007). Participants indicated at Time 2 how often they had experienced each of the following forms of neglect during their childhood on a 5-point scale (0 = Never to 4 = Six times or more): not take care of your basic needs (clean, food, clothing); leave you home alone when an adult should have been with you; ridicule or humiliate you; and treat you with coldness, indifference, or in a way that you felt unloved. A mean neglect score was computed (α = .71). Higher scores indicated greater experience of neglect.

Witnessing interparental violence was assessed using four items adapted from the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Participants were asked how many times they had witnessed their parents or caregivers engage in each of the four following violent behaviors toward one another (0 = Never to 3 = 11 or more times): insult, swear, shout or yell; threaten to hit or destroy the other person’s belongings; push, shove, slap, twist the arm, or throw something at the other person that could hurt; and threaten with a knife or a weapon, punch or kick, or slam the person against a wall. Respondents answered these four questions in terms of both violence by the father against the mother and violence by the mother against the father. A mean indicated greater exposure to interparental violence score was computed (α = .81). Higher scores indicated greater exposure to interparental violence.

Attachment security

Attachment security was assessed at Time 2 using the Experiences in Close Relationship Scale – Short Form (ECR-S; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998; Wei, Russell, Mallinckrodt, & Vogel, 2007), which was translated and adapted for the Quebec population (Lafontaine et al., 2016). The ECR-S measures two main dimensions of attachment: anxious and avoidant. Participants indicated on a 7-point scale (0 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree) how they generally feel in their romantic relationships (i.e., not only in their current relationship) with six items measuring anxious attachment (e.g., “I need a lot of reassurance that I am loved by my partner”) and six items on avoidant attachment (e.g., “I am nervous when partners get too close to me”). Lafontaine et al. (2016) described the high internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent and predictive validity of the ECR-S. Items were summed and averaged to form each subscale score. High scores indicated less attachment security (either anxious or avoidant), while low scores on each subscale indicated attachment security. In the current sample, the Cronbach’s alphas for anxious attachment and avoidant attachment were .67 and .69, respectively.

To test the hypotheses that anxious and avoidant attachment mediate the relationship between CM and SRBs, a theoretical temporal relationship had to be established between the variables. Thus, CM was measured at Time 1 and SRBs were assessed at Time 2 (6-month follow-up). Neglect was measured at Time 2 but referred to childhood experiences. Although attachment was assessed at the same time as SRBs in our study, Lafontaine et al. (2016) demonstrated the stability over a one-year period of attachment measured by the ECR-S.

Sexual risk behaviors

SRBs were assessed at Time 2. The number of sexual partners was measured with the following question: “In your lifetime, with how many people have you engaged in consensual sexual relations with penetration (oral, vaginal, or anal)?” Casual sexual behavior was assessed by asking if they had had consensual sexual contact (genital or breast touching, oral, vaginal, or anal penetration) in the past six months with an acquaintance or a stranger (1 = Yes, 0 = No). Participants who reported at least one sexual contact with an acquaintance or a stranger were categorized as having had casual sexual behavior (1 = Yes, 0 = No). Participants reported how old they were when they engaged in consensual sexual relations with penetration (oral, vaginal, or anal) for the first time. Age at first intercourse was used as a continuous variable, with younger age indicating higher sexual risk taking.

Covariates

Based on previous research and theory, mother’s education (coded as 1 =More than high school and 0 = High school or less) and family structure (coded as 1 = Separated parents or others and 0 = Living with their family of origin) were entered as covariates in each model (Fergusson, McLeod, & Horwood, 2013).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive and preliminary analyses were conducted using SPSS 20. Means, standard deviations, and correlations were computed to examine the relationships between study variables. The main hypotheses tests were performed in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012), which implements an appropriate estimation alternative for treating complex sample data, such as those in this representative survey. Prior to the data analyses, the variable number of sexual partners was transformed using winsorization (i.e., outliers in the top 1% [13 to 28] recoded to the 99th percentile value [12]) and the reflect of an inverse transformation to conform to normality assumptions.

To examine the relationships between CM, attachment security, and SRBs, path analyses were conducted. Missing data were accounted for using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method. FIML is a gold standard for handling missing data and uses all of the available data from each participant to generate the most likely population parameter estimates without discarding incomplete cases or imputing values (Enders, 2010). First, an analysis with forms of CM (i.e., sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect and witnessing violence) as predictors, anxious attachment and avoidant attachment as mediators, and continuous outcomes (i.e., number of sexual partners and age at first intercourse) was performed. We used bootstrap procedures to test the significance of the indirect effects. Bootstrapping is a method of resampling used to construct bias-corrected standard errors and confidence intervals (Edwards & Lambert, 2007).

Given the nonlinearity of relations involving a dichotomous outcome, a second analysis for casual sexual behavior was conducted separately using the weighted least squares means and variance adjusted estimation (WLSMV). WLSMV does not assume normally distributed variables and is considered to be the optimal technique for modeling binary outcomes (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Moreover, estimated coefficients were converted to probabilities, allowing for a more accurate interpretation of the results (Brown, 2006; Muthén & Muthén, 2009). Using formulas developed by Muthén and Muthén (2009), the probability of demonstrating casual sexual behavior for direct and indirect effects was calculated. The formula for the probability (P) of a direct effect was P (casual sexual behavior = 1|X1) = 1 – φ [(τ – λ1X1)/√θ], where X1 is the value of the given CM predictor, φ is the normal distribution function, τ is the threshold of the model, λ1 is the regression coefficient between the given CM predictor and demonstrating casual sexual behavior, and θ is the residual value of casual sexual behavior. The formula for the probability of an indirect effect was P (casual sexual behavior = 1|X1, X2) = 1 – φ[(τ – λ1X1 – λ2X2)/√θ], where X2 is the value of the mediator (anxious attachment or avoidant attachment) and λ2 is the regression coefficient between the mediator and casual sexual behavior.

As recommended by Kline (2010) and McDonald and Ho (2002), model fit was tested by considering the chi-square goodness-of-fit statistic, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) together. Less weight was given to the chi-square statistic, as significant values are common for models with large sample sizes. A combination of an RMSEA value less than .06, a CFI value greater than .90, and an SRMR value less than .10 indicates a good fit to the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2010).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Rates of child maltreatment by gender

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. A total of 48.5% of the sample (53.6% of girls and 39.5% of boys) reported at least one form of CM. For each form of CM, girls generally reported more experiences of CM than boys. In fact, in this sample 287 girls (24.9%) and 47 boys (6.4%) reported some form of sexual abuse in their lifetime at Time 1, with girls reporting significantly more experiences of sexual abuse χ2 (1) = 105.41, p < .001. Girls experienced more physical abuse by a family member χ2 (1) = 15.52, p < .001 (31.0% of girls and 22.7% of boys). Girls reported more experiences of neglect (M = .53, SD = .79) than boys (M = .36, SD = .65), t (1,589) = 4.07, p < .001. Finally, girls also reported more experiences of witnessing interparental violence (M = .42, SD = .47) than boys (M = .32, SD = .40), t (2,434) = 5.29, p < .001.

Table 1.

Information for Study Variables by Gender

| Variable | Range | Girls (n = 1,158)

|

Boys (n = 742)

|

Full sample (n = 1,900)

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or % | M (SD) or % | M (SD) or % | ||

| Age (in years) | 13–17 | 15.6 (.09) | 15.6 (.09) | 15.6 (.09) |

| Family structure | ||||

| Family of origin | 52.5 % | 58.7% | 54.9% | |

| Separated parents or others | 47.5 % | 41.3% | 45.1% | |

| Mother’s education | ||||

| High school or less | 35.6 % | 31.8% | 34.2% | |

| More than high school | 64.4 % | 68.2% | 65.8% | |

| Child maltreatment | ||||

| Sexual abuse | 0–1 | 24.9% | 6.4% | 17.7% |

| Sexual touching | 0–1 | 22.8% | 5.2% | 16.4% |

| Sexual intercourse | 0–1 | 10.4% | 2.9% | 7.6% |

| Physical abuse | 0–1 | 31.0% | 22.7% | 27.8% |

| Neglect | 0–4 | .53 (.04) | .36 (.03) | .47 (.03) |

| Witnessing interparental violence | 0–3 | .42 (.02) | .32 (.01) | .38 (.02) |

| Attachment style | ||||

| Avoidant attachment | 1–7 | 2.2 (.06) | 2.6 (.04) | 2.3 (.04) |

| Anxious attachment | 1–7 | 3.6 (.04) | 3.1 (.06) | 3.4 (.03) |

| Risky sexual behaviors | ||||

| Number of sexual partners (lifetime) | 1–12 | 2.6 (.15) | 3.0 (.19) | 2.7 (.13) |

| 1–2 | 65.5% | 59.8% | 63.5% | |

| 3–5 | 25.2% | 27.3% | 26.0% | |

| 6–12 | 9.3% | 12.9% | 10.5% | |

| Casual sexual behavior (6 months) | 0–1 | 15.9% | 25.3% | 19.2% |

| Age at first intercourse | 11–17 | 14.4 (.07) | 14.2 (.07) | 14.3 (.06) |

| 10–13 years old | 20.6% | 23.3% | 21.3% | |

| 14–15 years old | 64.4% | 63.4% | 64.1% | |

| 16 years old and older | 15.0% | 13.3% | 14.6% | |

Note. Casual sexual behavior represents sexual contacts with a stranger.

Rates of sexual risk behaviors by gender

At Time 2, girls and boys reported an average of 2.6 and 3.0 sexual partners in their lifetime, respectively. This difference was significant with a small effect size, t (1,113) = −2.96, p = .003, r = .09. Having engaged in casual sexual behavior between Time 1 and Time 2 was significantly more common among boys (25.3%) than girls (15.9%), χ2 (1) = 13.71, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .11. Finally, girls and boys in our sample of sexually active adolescents, respectively, reported an average age of 14.4 and 14.2 years at first intercourse, and this difference was significant with a small effect size, t (1,370) = 3.00, p = .003, r = .07.

Preliminary analyses

Table 2 presents bivariate correlations.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix for Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexual abuse | – | .06 | .26** | .16** | .08* | .10* | .19** | .13** | −.08* |

| 2. Physical abuse | .11* | – | .07 | .04 | .02 | .02 | .01 | −.02 | .04 |

| 3. Neglect | .15** | .13* | – | .37** | .18** | .17** | .20** | .16** | −.11** |

| 4. Witnessing interparental violence | .08 | .01 | .32** | – | .12** | .12** | .13** | .09* | −.04 |

| 5. Avoidant attachment | −.01 | .02 | .10* | .03 | – | .18** | .16** | .18** | −.08* |

| 6. Anxious attachment | .06 | .06 | .20** | .14** | −.02 | – | .15** | .14** | −.10** |

| 7. Number of sexual partners | .11* | .04 | .15** | .02 | .10* | .02 | – | .37** | −.40** |

| 8. Casual sexual behavior | .07 | .02 | .10 | −.02 | .15** | −.05 | .43** | – | −.15** |

| 9. Age at first intercourse | −.08 | −.08 | −.15** | −.04 | −.13** | −.00 | −.37** | −.15** | – |

Note. Boys’ correlations are below the diagonal and girls’ correlations are above the diagonal.

p < .05.

p < .01.

The Mediational Role of Attachment Security

Predicting Number of Sexual Partners and Age at First Intercourse

A path analysis was conducted to evaluate specific paths between forms of CM, attachment security, and continuous outcomes (i.e., number of sexual partners and age at first intercourse) (see Figure 2a). The results showed that the fit of the proposed model was good, χ2 (13) =56.68, p < .001, R2 = .04 (age at first intercourse) and .07 (number of sexual partners), RMSEA = .04, 90% CI (.03 to .05), CFI = .98, SRMR = .04.

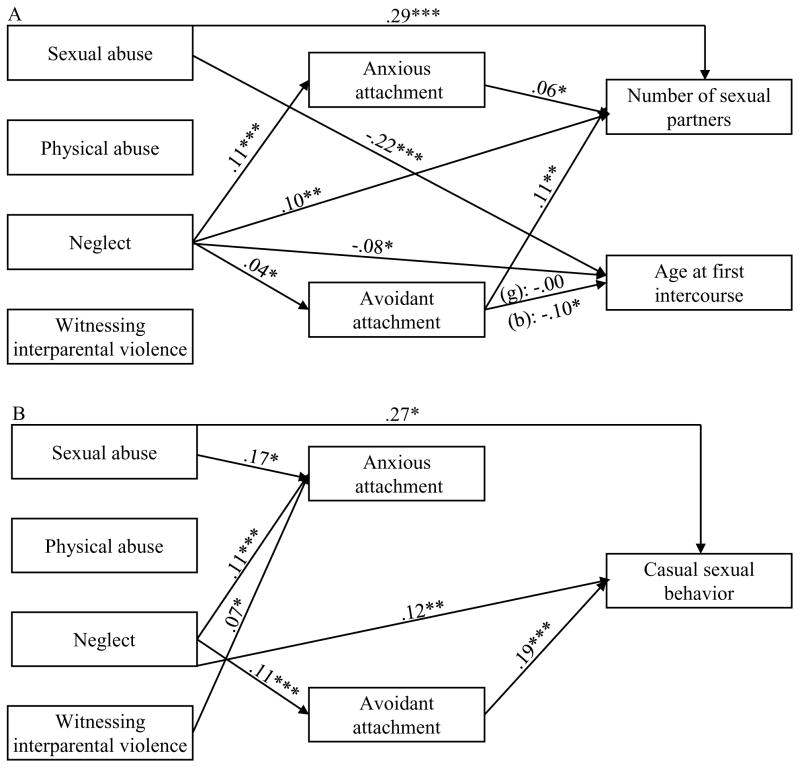

Figure 2.

Standardized coefficients for model of number of sexual partners and age at first intercourse (A) and model of casual sexual behavior (B). Differences among the two models for paths between CM and attachment are due to missing data. For clarity, control variables, covariances between variables measured at the same time, and non-significant standardized coefficients are not shown. Standardized coefficients for pathways that were found to differ by gender are provided above and below pathways lines for girls (g) and boys (b), respectively. *p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

After controlling for mother’s education and family structure, neglect was positively associated with anxious attachment and avoidant attachment. In turn, both anxious attachment and avoidant attachment were associated with having more sexual partners. Avoidant attachment was associated with a younger age at first intercourse for boys only. There was also a significant direct path both from neglect and sexual abuse to a higher number of sexual partners and younger age at first intercourse. Physical abuse and witnessing interparental violence were not associated with attachment security, number of sexual partners, or age at first intercourse.

Moreover, there was an indirect effect of neglect on a greater number of sexual partners via anxious attachment (β = .72, SE = .04, 95% CI [.09, 1.80]) and avoidant attachment (β = .40, SE = .21, 95% CI [.08, .99]). For age at first intercourse, there was a conditional indirect effect of neglect via avoidant attachment. Specifically, the indirect effect of neglect on age at first intercourse via avoidant attachment was significant for boys (β = −.56, SE = .30, 95% CI [−1.44, −.12]), but not for girls (β = −.21, SE = .15, 95% CI [−.65, .00]).

Predicting Casual Sexual Behavior

A second path analysis was performed to evaluate specific paths between forms of CM, attachment security, and the dichotomous outcome (i.e., casual sexual behavior) (Figure 2b). The results showed that the proposed model fit the data well, χ2 (16) = 29.93, p = .02, R2 = .11, RMSEA = .02, 90% CI (.01 to .04), CFI = .92.

After controlling for mother’s education and family structure, sexual abuse, neglect, and witnessing interparental violence were positively associated with anxious attachment. Only neglect was positively associated with avoidant attachment. In turn, only avoidant attachment was associated with casual sexual behavior. Anxious attachment was not associated with casual sexual behavior. There was also a significant direct path from neglect and sexual abuse to casual sexual behavior. Physical abuse was not associated with attachment or casual sexual behavior.

To allow for a more precise interpretation of the results, the probability of having casual sexual behavior was computed (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). For the direct effect of sexual abuse on casual sexual behavior, the probability of having casual sexual behavior among nonvictims (sexual abuse = 0) was .22. The probability increased to .31 for victims of sexual abuse (sexual abuse = 1). For the direct effect of neglect on casual sexual behavior, the probability of having casual sexual behavior for an average level of neglect was .22. The probability increased to .26 for a high level of neglect (i.e., +1 SD from the mean). For the indirect effect of neglect on casual sexual behavior via avoidant attachment, the probability of having casual sexual behavior for an average level of both neglect and avoidant attachment was .22. This probability increased to .28 when the level of avoidant attachment was high and to .33 when the level of both avoidant attachment and neglect was high.

Discussion

The present study examined a representative sample of high school adolescents to investigate the role of attachment insecurity in the association between CM and SRBs. Results on neglect are discussed first. Consistent with our hypothesis, neglect was directly associated with having a higher number of sexual partners in our subsample of sexually active adolescents (hypothesis 1). The association was explained by avoidant attachment, a finding that was also consistent with our expectations (hypothesis 2). Thus, experiences of neglect during childhood directly affect the way in which children interpret future relationships, resulting in discomfort with closeness and intimacy. Therefore, evading contact and closeness with others is associated with a higher number of sexual partners during adolescence. This result is consistent with the limited literature exploring this topic (Lemelin et al., 2014; Szielasko et al., 2013). We also found that anxious attachment was a significant mediator of the relationship between neglect and number of sexual partners. This result suggests that victims of neglect may consent to sexual contacts with a greater number of sexual partners to avoid feeling rejected and unloved. Our result was inconsistent with those of previous studies on young adults (Costa & Brody, 2011; Lemelin et al., 2014; Szielasko et al., 2013). As such, it could be possible that anxious attachment is associated with a higher number of sexual partners during adolescence but not in adulthood.

Also in line with our assumption, neglect was associated with a younger age at first intercourse (hypothesis 1). It was hypothesized that anxiously attached girls who experienced CM would accept sexual contact at a younger age because they want to avoid disapproval and rejection (hypothesis 3). However, this proposition was not supported by our results. The lack of an association between high levels of attachment anxiety and younger age at first intercourse in this study is consistent with the findings of Lemelin et al. (2014) but contradicts results established by Bogaert and Sadava (2002) and Gentzler and Kerns (2004). Our results are also inconsistent with the theoretical premise that adolescents who fear rejection and have a desperate need for closeness and intimacy may agree to engage in early sexual behaviors to maintain their relationships (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Results of the bivariate correlation analyses indicated a small association between anxious attachment and age at first intercourse for girls (r = −.08), which is consistent with results from Bogaert and Sadava (2002) and Gentzler and Kerns (2004). However, bivariate analyses in our study showed no association among boys (r =−.00). It is therefore possible that the small association found between anxious attachment and age at first intercourse among girls became nonsignificant when included in a multivariate model.

We also found that boys and girls who report having been neglected in childhood are more likely to engage in sexual intercourse at a younger age. A high level of attachment avoidance, but only for boys, explains this association. Based on our findings, avoidant attachment does not explain the relationship between neglect and a younger age at first intercourse for girls. However, for boys who have been neglected during childhood, discomfort with closeness and intimacy explains their tendency to engage in sexual intercourse at a younger age. This result is inconsistent with the findings of the Tracy et al. (2003) study indicating that avoidantly attached individuals were less likely to have ever had sexual intercourse than their secure and anxiously attached counterparts. Their results suggested a later age at first intercourse for avoidantly attached individuals, although the opposite was found in this study. Nevertheless, unlike our study, these researchers did not explore gender differences and included individuals who were not sexually active, which allowed for the detection of individuals who delayed their first sexual experience. Their findings combined with ours may imply two possible profiles in avoidantly attached adolescents: delayed onset or early onset of first intercourse. Our results may also suggest that attachment avoidance is manifested differently among boys and girls in regard to age at first intercourse. For example, it is possible that avoidant attachment is associated with a younger age at first intercourse for boys because their first experience was in a casual context. Moreover, as it is not socially accepted for girls to have many sexual partners and casual sexual behavior (Boislard et al., 2016), avoidantly attached girls may prefer to have their first sexual intercourse at the average age for first intercourse. Data regarding the type of sexual partner (casual or romantic) at first intercourse were not available in our study.

In alignment with our expectations, neglect in childhood was associated with having sexual contact with a stranger (casual sexual behavior) (hypothesis 1). Although the effect size is small, girls and boys who had been neglected were more likely to report casual sexual behavior. This association was partly explained by a high level of attachment avoidance (hypothesis 4). Unlike their secure peers, avoidantly attached adolescents value independence, have a low desire for emotional intimacy, and are less willing to commit to a long-term relationship to avoid being dissatisfied or disappointed (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). For avoidantly attached individuals, the preference for sexual contacts with strangers is still consistent with their relatively low desire for emotional intimacy. Furthermore, this result has been shown in numerous studies on college students (Garneau et al., 2013; Gentzler & Kerns, 2004; Paul et al., 2000). Our representative research allows those results to be generalized to the adolescent population. As expected, anxious attachment was not associated with casual sexual behavior, as documented by studies on college students (Garneau et al., 2013; Gentzler & Kerns, 2004; Paul et al., 2000). Conversely, anxious attachment would be associated with long-term mating strategies to fulfill needs for love, acceptance, and security (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

Our findings that adolescent attachment insecurity mediated the relationship between neglect and SRBs are consistent with attachment theory positing that working models shape behaviors later in life (Fraley & Shaver, 2000; Waters et al., 2000). A growing body of literature has demonstrated that the stress associated with CM and sexual abuse during childhood generates a cascade of vulnerabilities through insecure attachment on psychological and relational functioning and engagement in risk behaviors (Muller et al., 2012; Oshri et al., 2015; Owen et al., 2011). The present study showed that this conclusion also holds for SRBs during adolescence. Thus, adolescents who have been neglected might be dependent on others for approval and concerned about rejection (anxiously attached) or rather eschew intimacy and closeness (avoidantly attached). In turn, this vulnerability might lead them to have multiple sexual partners, casual sexual behaviors, and engage in first intercourse at a younger age in adolescence. Therefore, the attachment framework is a promising model for understanding the impact of neglect on SRBs during adolescence. In addition to the mediating effect of attachment, there was a direct pathway from neglect to all three SRBs in the present study. This finding suggests that attachment security does not fully capture the relationship between neglect and SRBs. Moreover, other mechanisms could potentially contribute to explaining the influence of neglect on SRBs.

Another major finding was the direct pathway from sexual abuse to all three SRBs for both boys and girls. This result was not surprising, as previous studies generally reported this finding (Senn et al., 2008). Our study adds to the existing literature by simultaneously considering several forms of CM, which supports the independent association between sexual abuse and SBRs. The path from sexual abuse to SRBs in our model was not explained by attachment avoidance or anxiety and could be mediated by an alternative mechanism, such as attitudes. The concept of traumatic sexualization described by Finkelhor and Browne (1985) may suggest a possible mediation. Traumatic sexualization refers to “a process in which a child’s sexuality (including both sexual feelings and sexual attitudes) is shaped in a developmentally inappropriate and interpersonally dysfunctional fashion” through rewards and attention (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985, p.531). Hoping to obtain affection and rewards, sexually abused adolescents might have multiple sexual partners. Moreover, powerlessness experienced during sexual abuse could influence victims to believe that they are unable to control sexual situations, making it difficult for them to refuse sex (e.g., multiple sexual partners, casual sexual behavior, and younger age at first intercourse). Consequently, sexual abuse and neglect may act through distinct pathways.

It is important to note that these results do not suggest that sexual abuse has no effect on attachment security. Rather, they may reflect the fact that neglect is the form of CM that is more closely related to attachment due to the context in which the child feels rejected and undeserving (negative internal working models). Furthermore, it may also reflect the high co-occurrence of neglect with other forms of CM. In fact, there is growing evidence that children who experience sexual or physical abuse in a family environment are likely to experience neglect as well. Therefore, in a multivariate model including sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect, and witnessing interparental violence, it is plausible that when the effect of neglect on attachment is accounted for, the effect of other forms of CM will be nonsignificant. For example, in the present study, there were significant bivariate associations between three forms of CM (sexual abuse, neglect, and witnessing interparental violence) and anxious and avoidant attachment.

This research considered several forms of CM, controlled for mother’s education and family structure, and explored gender differences. The current model accounted for a significant proportion of the relationship between CM and SRBs (variance explained [R2] ranged from 4% to 11%). However, much of the relationship between CM and SRBs remains unexplained and effects were mostly small to moderate. This finding is not surprising, given that sexual behaviors are driven by multiple determinants (Dewitte, 2014). The current study was one of the few to investigate the mechanisms underlying CM and their associations with SRBs. We used a representative sample of high school adolescents to enhance the generalizability of the findings. The prospective nature of this study, with CM being measured at Time 1 and SRBs being measured at Time 2, lends greater predictive power to the findings.

Despite these strengths, our findings should be considered in light of several limitations. The first limitations arise from the absence of a longitudinal design. As age at which CM occurred was not measured, there could be a temporal overlap for some participants between CM and two SRBs (i.e., number of sexual partners and age at first sexual intercourse). Thus, conclusions should be interpreted with caution regarding causality, especially for those two SRBs. Also, we inquired about CM at Time 1, but the items were retrospective and participants were susceptible to bias recall (overestimation or underestimation). Moreover, attachment might have influenced recall of CM because avoidant individuals tend to idealize their caregivers and cannot recall negative experiences in their childhood (Mikulincer & Orbach, 1995; Pereg & Mikulincer, 2004). A second set of limitations concerns exclusion criteria. In fact, participants who never had sexual contacts were excluded given that the topic concerned SRBs. Moreover, participants who had never been in a romantic relationship could not complete the attachment measure and were excluded. This exclusion criterion likely resulted in the removal of some secure or avoidantly attached adolescents from the sample. However, such a bias would tend to reduce the likelihood of finding significant effects on SRBs, which was not the case in the present study. The third limit is related to our physical abuse measure, which was not extensive and may have led to confusion concerning physical violence by the siblings and by the parents. Such ambiguity may explain the lack of significant findings. Several studies have demonstrated the association between physical abuse and SRBs (Norman et al., 2012). Finally, social desirability has to be considered. Studies have showed that SRBs are likely to be underestimated in studies, as they are perceived as socially unacceptable (Brener, Billy, & Grady, 2003). In return, it may be socially acceptable for some subgroups (e.g., for boys) to have had many sexual experiences (e.g., more sexual partners and casual partners) (Boislard et al., 2016; Brener et al., 2003). Thus, several strategies were used to minimize biases (Bradburn, Sudman, & Wansink, 2004), such as self-report questionnaires (rather than face-to-face interviews) and anonymous surveys (questionnaires returned in a sealed envelope and anonymous codification to link all the questionnaires).

More research is needed to explore patterns in SRBs among victims of CM and their attachment level in terms of avoidance and anxiety. Future studies should also measure attachment security in adolescents who have never had a romantic relationship (e.g., Attachment Style Questionnaire). Moreover, a longitudinal design could not only detect changes in attachment security from young adolescence to young adulthood but also provide dynamic developmental data on the potentially reciprocal association between changes in attachment security and SRBs during an important life transition. Future research is also needed to clarify other mechanisms through which CM may lead to SRBs during adolescence.

The mediating role of attachment avoidance and anxiety may have implications for prevention and intervention. Programs aimed at promoting sexual health and reducing SRBs should be adapted for adolescents who have experienced neglect and sexual abuse. In particular, such programs should be implemented in environments marked by neglect and abuse and in clinical settings where services are provided to neglected children and adolescents. Furthermore, interventions targeting positive changes in attachment security may reduce SRBs among adolescents with a history of neglect.

References

- Baer JC, Martinez CD. Child maltreatment and insecure attachment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2006;24:187–197. doi: 10.1080/02646830600821231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M, Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e278–e290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert AF, Sadava S. Adult attachment and sexual behavior. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:191–204. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boislard MA, van de Bongardt D, Blais M. Sexuality (and lack thereof) in adolescence and early adulthood: A review of the literature. Behavioral Sciences. 2016;6:8. doi: 10.3390/bs6010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Attachment. 2. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn NM, Sudman S, Wansink B. Asking threatening questions about behavior. In: Bradburn NM, Sudman S, Wansink B, editors. Asking questions: The definitive guide to questionnaire design. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 79–116. Revised ed. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Bolus R, Mayer EA. Psychometric properties of the Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:211–218. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243824.84651.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Billy JOG, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: Evidence from the scientific literature. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:436–457. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self report measurement of adult attachment. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Child abuse trauma: Theory and treatment of the lasting effects. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Treating adult survivors of severe childhood abuse and neglect: Further development of an integrative model. In: Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, Hendrix CT, Jenny C, Reid TA, editors. The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002. pp. 175–203. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Pioli M, Levitt A, Talley AE, Micheas L, Collins NL. Attachment styles, sex motives, and sexual behavior: Evidence for gender-specific expressions of attachment dynamics. In: Mikulincer M, Goodman GS, editors. Dynamics of romantic love: Attachment, caregiving, and sex. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 243–274. [Google Scholar]

- Costa RM, Brody S. Anxious and avoidant attachment, vibrator use, anal sex, and impaired vaginal orgasm. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011;8:2493–2500. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr C, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH. Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:87–108. doi: 10.1017/s0954579409990289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, Shaver PR, Vernon ML. Attachment style and subjective motivations for sex. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1076–1090. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte M. On the interpersonal dynamics of sexuality. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2014;40:209–232. doi: 10.1080/0092623x.2012.710181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:1–22. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott GC, Avery R, Fishman E, Hoshiko B. The encounter with family violence and risky sexual activity among young adolescent females. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:569–592. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.5.569.33710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Maximum likelihood missing data handling. In: Enders CK, editor. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 86–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA, Caldwell CH. Growth trajectories of sexual risk behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1096–1101. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, McLeod GFH, Horwood LJ. Childhood sexual abuse and adult developmental outcomes: Findings from a 30-year longitudinal study in New Zealand. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:664–674. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:632–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1990;14:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:149–166. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology. 2000;4:132–154. doi: 10.1037//1089-2680.4.2.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garneau C, Olmstead SB, Pasley K, Fincham FD. The role of family structure and attachment in college student hookups. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentzler AL, Kerns KA. Associations between insecure attachment and sexual experiences. Personal Relationships. 2004;11:249–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00081.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lee Y, Ozonoff A, Wert MJ. The impact of multiple types of child maltreatment on subsequent risk behaviors among women during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:528–540. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9490-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling-a Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine MF, Brassard A, Lussier Y, Valois P, Shaver PR, Johnson SM. Selecting the best items for a short-form of the Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2016;32:140–154. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemelin C, Lussier Y, Sabourin S, Brassard A, Naud C. Risky sexual behaviours: The role of substance use, psychopathic traits, and attachment insecurity among adolescents and young adults in Quebec. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2014;23:189–199. doi: 10.3138/cjhs.2625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Radecki Breitkopf C, Berenson A. Sexual and physical abuse history and adult sexual risk behaviors: Relationships among women and potential mediators. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:757–768. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Ho MHR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Orbach I. Attachment styles and repressive defensiveness: The accessibility and architecture of affective memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:917–925. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.5.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment processes and couple functioning. In: Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, editors. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 285–323. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Pereg D. Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27:77–102. doi: 10.1023/a:1024515519160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RT, Thornback K, Bedi R. Attachment as a mediator between childhood maltreatment and adult symptomatology. Journal of Family Violence. 2012;27:243–255. doi: 10.1007/s10896-012-9417-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus short courses topic 2: Regression analysis, exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and structural equation modeling for categorical, censored, and count outcomes. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, Schneiderman JU, Trickett PK. Child maltreatment and sexual risk behavior: Maltreatment types and gender differences. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2015;36:708–716. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olley BO. Child sexual abuse as a risk factor for sexual risk behaviours among socially disadvantaged adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2008;3:243–248. doi: 10.1080/17450120802385737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oshri A, Sutton TE, Clay-Warner J, Miller JD. Child maltreatment types and risk behaviors: Associations with attachment style and emotion regulation dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;73:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Quirk K, Manthos M. I get no respect: The relationship between betrayal trauma and romantic relationship functioning. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2011;13:175–189. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2012.642760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul EL, McManus B, Hayes A. “Hookups”: Characteristics and correlates of college students’ spontaneous and anonymous sexual experiences. Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:76–88. doi: 10.1080/00224490009552023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereg D, Mikulincer M. Attachment style and the regulation of negative affect: Exploring individual differences in mood congruency effects on memory and judgment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:67–80. doi: 10.1177/0146167203258852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Storey K. Cumulative abuse: Do things add up? An evaluation of the conceptualization, operationalization, and methodological approaches in the study of the phenomenon of cumulative abuse. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2011;12:135–150. doi: 10.1177/1524838011404253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott ME, Wildsmith E, Welti K, Ryan S, Schelar E, Steward–Streng NR. Risky adolescent sexual behaviors and reproductive health in young adulthood. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011;43:110–118. doi: 10.1363/4311011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP. Child maltreatment and women’s adult sexual risk behavior: Childhood sexual abuse as a unique risk factor. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:324–335. doi: 10.1177/1077559510381112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: Evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:711–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szielasko AL, Symons DK, Price LE. Development of an attachment-informed measure of sexual behavior in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourigny M, Hébert M, Joly J, Cyr M, Baril K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of violence against children in the Quebec population. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2008;32:331–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy JL, Shaver PR, Albino DAW, Cooper ML. Attachment styles and adolescent sexuality. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 137–159. [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Poly-Victimization in a national sample of children and youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Merrick S, Treboux D, Crowell J, Albersheim L. Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development. 2000;71:684–689. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, Vogel DL. The Experiences in Close Relationship scale (ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;88:187–204. doi: 10.1080/00223890701268041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: A 30-year follow-up. Health Psychology. 2008;27:149–158. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Woods BA, Emerson E, Donenberg GR. Patterns of violence exposure and sexual risk in low-income, urban African American girls. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2:194–207. doi: 10.1037/a0027265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]