Abstract

Acute respiratory distress syndrome constitutes a significant disease burden with regard to both morbidity and mortality. Current therapies are mostly supportive and do not address the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms. Removal of protein-rich alveolar edema—a clinical hallmark of acute respiratory distress syndrome—is critical for survival. Here, we describe a transforming growth factor (TGF)-β–triggered mechanism, in which megalin, the primary mediator of alveolar protein transport, is negatively regulated by glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) 3β, with protein phosphatase 1 and nuclear inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1 being involved in the signaling cascade. Inhibition of GSK3β rescued transepithelial protein clearance in primary alveolar epithelial cells after TGF-β treatment. Moreover, in a bleomycin-based model of acute lung injury, megalin+/– animals (the megalin–/– variant is lethal due to postnatal respiratory failure) showed a marked increase in intra-alveolar protein and more severe lung injury compared with wild-type littermates. In contrast, wild-type mice treated with the clinically relevant GSK3β inhibitors, tideglusib and valproate, exhibited significantly decreased alveolar protein concentrations, which was associated with improved lung function and histopathology. Together, we discovered that the TGF-β–GSK3β–megalin axis is centrally involved in disturbances of alveolar protein clearance in acute lung injury and provide preclinical evidence for therapeutic efficacy of GSK3β inhibition.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, protein transport, pulmonary edema, transforming growth factor β, alveolar epithelium

Clinical Relevance

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a leading cause of mortality in the intensive care unit, and despite enormous efforts, no effective pharmacological therapy exists. Removal of protein-rich alveolar edema—a clinical hallmark of ARDS—is critical for survival and thus represents a promising target of therapeutic intervention. We describe for the first time a unique TGF-β–triggered and GSK3β-mediated pathway that negatively regulates megalin, the major mediator of alveolar protein clearance, and provide preclinical evidence for therapeutic efficacy of GSK3β inhibition in ARDS.

With an incidence of approximately 200,000 patients annually in the United States, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) constitutes a significant disease burden with regard to both morbidity and mortality (1, 2). Treatment strategies for ARDS are supportive, and do not address the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms. The accumulation of protein-rich alveolar edema (protein concentrations reach approximately 40–90% of plasma levels [3]), secondary to endothelial and epithelial injury, causes severe impairment of gas exchange and, therefore, hypoxia, which lead to further disruption of alveolar epithelial function and fluid balance (4). Elevated levels of precipitated protein can be found in the alveolar space of patients with ARDS. Importantly, nonsurvivors of ARDS exhibit threefold-higher levels of precipitated protein in edema fluid than do survivors of the disease (5). Therefore, removal of excess protein from the alveolar space is essential for the resolution of ARDS. We have previously demonstrated that, in rabbit lungs as well as in primary alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) monolayers, albumin (the most abundant protein in the plasma) is actively transported across the alveolar epithelial barrier by a high-capacity endocytic process mediated by megalin, a 600-kD glycoprotein member of the low-density lipoprotein receptor superfamily (6, 7).

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β has been described as a key mediator, not only of the late fibroproliferative phase of ARDS, but also in early injury (8). In various murine models of acute lung injury (ALI), TGF-β impairs epithelial permeability and transepithelial sodium transport capacity, thus promoting pulmonary edema (9, 10). Similar findings have been described in human patients with ARDS (8, 11).

Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) 3 is a ubiquitously expressed, highly conserved serine/threonine protein kinase signaling molecule found in all eukaryotes (12). GSK3 participates in a wide spectrum of cellular processes, including glycogen metabolism, transcription, translation, cytoskeleton regulation, intracellular vesicular transport, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis (12–14). In the cell, GSK3 is constitutively phosphorylated, and thereby inactivated. To be activated, GSK3 must be dephosphorylated (14, 15). Mammals express two GSK3 isoforms, GSK3α (51 kD) and GSK3β (47 kD), that are 98% structurally identical (13, 16). GSK3β is the more abundant and better understood isoform, as several studies have linked GSK3β dysregulation, particularly hyperactivation, with various pathological conditions, including diabetes mellitus, inflammation, pulmonary hypertension, and Alzheimer’s disease (16–19). Thus, GSK3 inhibitors comprise an interesting group of potential therapeutics for human disease.

In the present study, using primary alveolar type II cells, human A549 cells, and a murine model of ALI, we demonstrate that inhibition of GSK3β increases protein clearance, and thus promotes the resolution of ALI. In addition, we identify a novel molecular pathway linking activation of TGF-β to GSK3β. Collectively, our findings may suggest a potential role for GSK3β inhibition as a novel therapeutic approach in ARDS.

Materials and Methods

Methodologies addressing alveolar epithelial gene transfer, assessment of signaling molecules, lung function, and injury in the model of bleomycin-induced ALI have been described in detail previously (6, 7, 20–23). A brief description of materials and methodologies is provided in the online supplement.

Study Approval

All animal experiments were conducted according to the legal regulations of the German Animal Welfare Act or National Institutes of Health guidelines, and were approved by the regional authorities of the State of Hessen or by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Colorado (Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO), respectively.

Experimental ALI Groups

Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 or heterozygous megalin knockout mice (6- to 8-wk old, 20–25 g; megalin+/−; a generous gift of Prof. T. E. Willnow, Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany [24]) were orotracheally injected with bleomycin (3.5 U/kg; Sigma, Seelze, Germany) in 80 μl of 0.9% saline. Control mice were given 80 μl of 0.9% saline orotracheally. In the treatment groups, WT mice were treated 2 days before and for 10 days after bleomycin challenge daily with either valproate (VPA; 150 mg/kg intraperitoneally or 60 mg/kg orotracheally) or vehicle. In subsequent experimental groups, mice were treated 2 days before and for 10 days after bleomycin challenge every other day with either tideglusib (20 mg/kg orotracheally) or vehicle.

Cellular Binding, Uptake, and Transepithelial Transport of FITC-Albumin

Primary rat AECs were used on Day 3 after isolation. Cells were plated on permeable supports (BD Falcon, Heidelberg, Germany). Experiments were performed on tight monolayers, defined by transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) of greater than 1,200 Ω·cm2. A549 cells were plated on 60-mm cell culture dishes. Measurements of cellular binding, uptake, and transepithelial transport of FITC-labeled albumin have been described previously (6, 7). Briefly, cells were incubated with 50 μg/ml FITC-albumin dissolved in Dulbecco’s PBS containing 5 mM glucose (DPBS-G; PAN Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany) and 0.1 mM CaCl2 dihydrate (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), 0.5 mM MgCl2·6H2O for 1 hour. At the end of the experiments, buffer samples were taken from the basolateral side of the permeable support to assess transepithelial transport of FITC-albumin. Cells were then rinsed three times with ice-cold PBS and were incubated with 0.5 ml of ice-cold Solution X (DPBS-G, 0.5 mg/ml trypsin, 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K, 0.5 mM EDTA) before being scraped off the permeable support or cell culture dish. After centrifugation from the supernatant to assess the bound fraction (binding of FITC-albumin to the cell surface), the pellet was solubilized in 0.5 ml 0.1% Triton-X-100 to measure taken-up FITC-albumin. Fluorescence was detected using an Infinite 200 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Tecan, San Jose, CA) at an excitation wavelength of 500 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm.

Statistical Analysis

Numerical values are given as the mean (±SEM). Comparisons between two groups were performed using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. Intergroup differences of three or more experimental groups were assessed by using a one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferoni test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. GraphPad Prism 6 for Windows software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) was used for data plotting and statistical analysis.

Results

TGF-β Impairs Transepithelial Protein Transport

We and others have recently shown that megalin drives the transepithelial clearance of albumin, the most abundant plasma protein, through the intact alveolar epithelium (6, 7, 25). To assess the pathophysiological relevance of megalin-mediated removal of excess alveolar protein content, we subjected heterozygous megalin knockout mice to bleomycin-induced ALI. We used heterozygous animals, because homozygous megalin knockout mice die perinatally due to respiratory failure (24), probably as a consequence of impaired protein and, thus, fluid removal, from the alveolar space. Importantly, heterozygous megalin knockout mice, in which a marked decrease in megalin protein expression in peripheral lung tissues was evident (see Figure E1A in the online supplement), treated with bleomycin exhibited a more severe lung injury (Figures 1A and 1B), increased protein content of the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (Figure 1C), and more pronounced weight loss 10 days after bleomycin treatment (Figure 1D) compared with WT littermate controls, indicating more manifest animal stress. In contrast, BAL cell counts and differentials were not affected by megalin expression (Figure E1B).

Figure 1.

Heterozygous megalin knockout mice display impaired protein clearance and more severe lung injury than wild-type (WT) littermates. WT C57BL/6 or heterozygous megalin knockout mice (megalin+/−; 6- to 8-wk old, 20–25 g) were orotracheally injected with bleomycin (Bleo) (3.5 U/kg in 80 μl of 0.9% saline) or 80 μl of 0.9% saline alone. At 10 days after bleomycin treatment, the severity of acute lung injury (ALI) was assessed. (A) Representative examples of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained lung tissues from control (vehicle-treated) mice, and bleomycin-induced ALI in WT littermates or megalin+/− mice are shown. Scale bar: 50 μm. ALI score (B) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) protein concentration (C) in WT or megalin+/− mice treated with vehicle or bleomycin at Day 10 after treatment and body weight (D) at baseline and on Days 2, 6, and 10 after treatment are depicted. Data represent mean (±SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n = 4–7 per group. n.s., not significant.

As TGF-β is a key mediator of ALI, we next set out to determine whether TGF-β regulated the megalin-mediated alveolar protein clearance. Application of pathophysiologically relevant concentrations of TGF-β to primary alveolar epithelial type (AT) II cells significantly decreased albumin uptake, which was completely restored by the TGF-β receptor antagonist, SB431542 (Figure 2A). Furthermore, TGF-β stimulation led to a decrease in megalin cell surface abundance (Figures 2B and 2C). In line with these findings, transfecting primary AECs with a small interfering RNA (siRNA) directed against megalin using nucleofection also resulted in a significant decrease in binding, uptake, and transport of FITC-albumin, which was even more pronounced than in AECs treated with TGF-β alone (Figures 2D–2F). Of note, paracellular permeability remained unaltered in all experimental conditions (Figure E2). The cytoplasmatic domain of megalin contains a PPPSP motif, representing a GSK3 phosphorylation site. It has been demonstrated that GSK3 activity is necessary for phosphorylation of megalin, leading to subsequent reduction of megalin cell surface stability (26). We therefore transfected A549 cells with a 17-amino-acid oligopeptide sequence of the intracellular megalin domain containing the PPPSP motif, thus saturating GSK3 binding sites in the cell, and found a prevention of the TGF-β–induced decrease in FITC-albumin binding and uptake in a concentration-dependent manner (Figures 2G and 2H), whereas application of the oligopeptide alone did not affect cellular binding or uptake of FITC-albumin (Figure E3).

Figure 2.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 impairs transepithelial alveolar protein transport. (A) Alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) were treated with TGF-β1 for 30 minutes in the presence or absence of the TGF-β1 receptor antagonist, SB431542 (10 μM), before a 1-hour incubation with FITC-albumin. FITC-albumin uptake was then determined as described in the Materials and Methods section. (B and C) After a 30-minute treatment with TGF-β1, megalin membrane abundance was detected by biotinylation and pulldown of cell-surface proteins and subsequent immunoblotting and compared with vehicle-treated control (Ctrl). Transferrin receptor (Tfr) in the plasma membrane (PM) fraction and megalin and Tfr protein abundance of whole cell lysate samples (WCL) served as loading controls. (D–F) AECs transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) against megalin were used 48 hours after transfection. Successful silencing of megalin was assessed by Western blot analysis. Cells treated with vehicle (ctrl) or TGF-β1 for 30 minutes in the presence of a scrambled siRNA served as controls. Binding, uptake, and transepithelial transport of FITC-albumin were determined 1 hour after incubation with FITC-albumin by fluorescence. (G and H) Cells were transfected with a peptide mimicking the intracellular domain of megalin and then treated with TGF-β1 for 30 minutes. FITC-albumin binding (D) and uptake (E) were determined by fluorescence and compared with sham-transfected cells. Data represent the mean (±SEM). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; n = 3–4 for all experiments.

GSK3β Mediates the TGF-β1–Induced Decrease in Transepithelial Protein Clearance

GSK3β is activated either by dephosphorylation at serine-9 (15) or phosphorylation at tyrosine-216 (27). In primary AECs TGF-β stimulation led to pronounced dephosphorylation of serine-9, and thus activation of GSK3β (Figure 3A), without affecting the phosphorylation status of tyrosine-216 (Figure E4). In line with these findings, AECs transfected with a constitutively active form of GSK3β (GSK3βS9A) exhibited decreased epithelial clearance of FITC-albumin (Figures 3A–3C). Conversely, in AECs in which GSK3β expression was abrogated by siRNA directed against GSK3β, epithelial clearance of FITC-albumin was unaffected by exposure to TGF-β. In cells not treated with TGF-β, but transfected with siRNA directed against GSK3β, alveolar albumin clearance was not significantly different from baseline (Figures 3D–3F). Collectively, these data suggested that GSK3β was critically required for the TGF-β–induced inhibition of epithelial protein transport. As Akt is a known upstream regulator of GSK3β (14), we investigated a potential role for Akt in transepithelial albumin transport, and found that neither chemical inhibition nor genetic ablation of the Akt influenced epithelial protein clearance (Figure E5). Furthermore, it has been established that GSK3β is an integral part of the Wnt signaling pathway (28). However, interestingly, suppression of β-catenin did not alter epithelial protein clearance either (Figure E6), suggesting that neither the Akt nor the Wnt signaling pathway was involved in mediating the impaired protein transport upon TGF-β exposure.

Figure 3.

Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) 3β mediates the TGF-β1–induced decrease in transepithelial protein clearance. (A, upper panel) Serum-starved AECs were treated with TGF-β1 and were lysed at the indicated time points, and phosphorylation status of GSK3β at the serine-9 residue was assessed by Western blot analysis. A representative Western blot is shown. Data represent mean (±SEM). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (A, middle panel) At 24 hours after isolation, AECs were transfected with a constitutively active GSK3βS9A or an empty vector (EV) and activation of GSK3β was measured as described above. A representative Western blot is shown. Data represent mean (±SEM). *P < 0.05. AECs were treated with TGF-β1 or transfected with GSK3βS9A, as described above, and FITC-albumin binding (A, lower panel), uptake (B), or transepithelial transport (C) were measured by fluorescence after 1-hour incubation (n = 6). Data represent mean (±SEM). ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (D, upper panel) AECs were transfected with a scrambled siRNA (ctrl) or a specific siRNA against GSK3β and, 48 hours later, cells were exposed to TGF-β or vehicle for 30 minutes and subsequently to FITC-albumin for 1 hour, and binding (D, lower panel), uptake (E), and transepithelial transport (F) of FITC-albumin were measured by fluorescence (n = 6). Data represent mean (±SEM). ****P < 0.0001.

Protein Phosphatase 1 Is an Upstream Activator of GSK3β

GSK3β must be dephosphorylated to be active, and the protein phosphatases (PPs), PP1 and PP2A, have been implicated in the regulation of GSK3β (29, 30). To investigate whether PP1 or PP2 was involved in the TGF-β–induced dephosphorylation of GSK3β, AECs were incubated with the PP inhibitor calyculin A (CA; PP1>>PP2 inhibitor) or okadaic acid (OA; PP2>>PP1 inhibitor). Interestingly, the PP1 inhibitor, CA, prevented the TGF-β–induced dephosphorylation of GSK3β, whereas OA had no effect on GSK3β phosphorylation (Figure 4A). In line with these data, in AECs, CA (but not OA) attenuated the TGF-β1–mediated inhibition of epithelial albumin binding, uptake, and transport (Figures 4A–4C). These findings were further confirmed by fluorescence microscopy. AECs incubated with FITC-albumin (Figure 4D) exhibited increased uptake of FITC-albumin when treated with CA (compared with OA) after TGF-β1 exposure. Moreover, in AECs transfected with an siRNA against PP1 (siPP1), levels of inactive phospho-GSK3β were increased, even in the presence of TGF-β (Figure 4E, upper panels). Complementary to this observation, overexpression of the catalytic γ subunit of PP1 in AECs resulted in a significant decrease in the levels of phospho-GSK3β, independent of TGF-β effects (Figure 4E, lower panel). The upstream regulation of GSK3β by PP1 was also reflected by the effect of PP1 on epithelial clearance of FITC-albumin. Transfection with siPP1 abrogated the TGF-β–induced blunting of albumin binding, uptake, and transepithelial transport, whereas overexpression of the active PP1 γ subunit led to a decrease in epithelial albumin clearance comparable to AECs exposed to TGF-β1 (Figures 4F–4H), suggesting that the TGF-β–induced impairment of albumin transport required PP1 activity, leading to dephosphorylation of GSK3β.

Figure 4.

Protein phosphatase (PP) 1 is an upstream activator of GSK3β. Serum-starved AECs were incubated with inhibitors of PP1 (10 nm calyculin A [CA]) or PP2 (2 nm okadaic acid [OA]) for 1 hour before treatment with TGF-β1 for 5 minutes. (A, upper panel) Phosphorylation status of GSK3β at the Ser-9 residue was assessed by Western blot analysis. Representative immunoblots are shown. Data represent mean (±SEM). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 (n = 3). (A, middle panel). Vehicle-, CA-, or OA-treated AECs were exposed to TGF-β or solvent for 30 minutes and subsequently to FITC-albumin for 1 hour and binding (A, lower panel), uptake (B), and transepithelial transport (C) of FITC-albumin were measured (n = 4). Data represent mean (±SEM). ***P < 0.001. (D) Representative fluorescent microscopic images showing the cellular uptake of FITC-albumin in AECs in the presence or absence of TGF-β and the PP1 and PP2 inhibitors, CA and OA, respectively, identical to the treatment protocol described above. Scale bars: 50 μm. AECs were transfected with siPP1 (E, upper panels) or the catalytic PP1γ subunit (E, middle and lower panel). At 48 hours after transfection, cells were serum starved and treated for 5 minutes with TGF-β1. Cells were then lysed and phosphorylation status of GSK3β at the Ser-9 residue was assessed by Western blot analysis. Representative immunoblots are shown. Data represent mean (±SEM). **P < 0.01 (n = 3). AECs were transfected with siPP1 or PP1γ, as described above, and were exposed to TGF-β1 or vehicle for 30 minutes and subsequently to FITC-albumin for 1 hour and binding (F), uptake (G), and transepithelial transport (H) of FITC-albumin were measured (n = 4). Data represent mean (±SEM). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Nuclear Inhibitor of PP1 Inhibits PP1 and thus Acts as an Upstream Regulator of GSK3β

A major interaction partner of PP1 is the nuclear inhibitor of PP1 (NIPP1) (23, 31, 32). Thus, we hypothesized that silencing NIPP1 may increase the amount of free PP1, and therefore activate GSK3β. Indeed, A549 cells transfected with siNIPP1 displayed decreased phospho-GSK3β expression levels, similar to cells stimulated with TGF-β. Notably, in cells transfected with siNIPP1, phospho-GSK3β expression was impervious to TGF-β challenge (Figure 5A). Consistent with phospho-GSK3β expression at the protein level, in A549 cells transfected with siNIPP1, the binding and uptake of FITC-albumin was significantly decreased (Figures 5B and 5C). In contrast, A549 cells expressing a forkhead-associated domain variant (NIPP1-FHA) with altered mRNA splicing ability, but unchanged PP1 affinity, displayed GSK3β activation (Figure 5D) and albumin binding and uptake rates and responsiveness to TGF-β similar to that of NIPP1-WT–transfected AECs (Figures 5E and 5F). Collectively, these findings suggest that, upon TGF-β exposure, activation of PP1 requires release of the phosphatase from the inhibitory binding partner, NIPP1.

Figure 5.

Nuclear inhibitor of PP1 (NIPP1) inhibits PP1 and thus acts as an upstream regulator of GSK3β activity. (A) AECs were transfected with a scrambled siRNA (ctrl) or a specific siRNA against NIPP1 (siNIPP1). At 48 hours after transfection, cells were serum starved and treated for 5 minutes with TGF-β1. Cells were then lysed and phosphorylation status of GSK3β at the Ser-9 residue was assessed by Western blot analysis. Representative immunoblots are shown. Data represent mean (±SEM). **P < 0.01 (n = 3). At 48 hours after transfection with siNIPP1 or a scrambled siRNA, AECs were serum starved and treated with TGF-β1 or vehicle for 30 minutes and were subsequently exposed to FITC-albumin for 1 hour, and binding (B) and uptake (C) of FITC-albumin were measured. Data represent mean (±SEM). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (n = 4–5). (D) AECs were transfected with WT NIPP1 or a forkhead-associated domain variant of NIPP1 (FHA). At 48 hours after transfection, cells were serum starved and treated for 5 minutes with TGF-β1, and phosphorylation status of GSK3β at the Ser-9 residue was assessed by Western blot analysis. Representative immunoblots are shown. Data represent mean (±SEM). **P < 0.01 (n = 3). At 48 hours after transfection with WT or FHA NIPP1, AECs were serum starved and treated with TGF-β1 or vehicle for 30 minutes and were subsequently exposed to FITC-albumin for 1 hour, and binding (E) and uptake (F) of FITC-albumin were measured. Data represent mean (±SEM). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (n = 4–5).

Pharmacological Inhibition of GSK3β after TGF-β1 Treatment Restores Transepithelial Albumin Clearance

Our findings suggest that GSK3β activity is a critical step in the regulation of transepithelial albumin clearance. Therefore, pharmacological inhibitors of GSK3β are an intriguing therapeutic possibility for ALI, as these inhibitors directly target one of the major underlying pathophysiologic principles. We first set out to determine whether clinically applicable pharmacologic GSK3β inhibitors, such as VPA or tideglusib, increase transepithelial albumin clearance in vitro. Importantly, in AECs, incubation with VPA or tideglusib prevented the TGF-β–induced dephosphorylation of GSK3β (Figure 6A). Figure 6B depicts AECs that were treated with VPA or tideglusib after TGF-β exposure. Notably, a marked increase in FITC-albumin uptake in these cells was evident. To support this observation, we first exposed AECs grown on cell-culture inserts to TGF-β for 30 minutes before incubation with the respective GSK3β inhibitor, and again found rescued FITC-albumin binding, uptake, and transport, comparable to control conditions (Figures 6C–6E).

Figure 6.

Pharmacological inhibition of GSK3β after TGF-β1 treatment restores transepithelial albumin clearance. (A) AECs were treated with the GSK3β inhibitors, valproate (VPA; 1.5 mM) or tideglusib (1.5 μM), for 30 minutes and then exposed to TGF-β or vehicle for 5 minutes, and phosphorylation status of GSK3β at the Ser-9 residue was assessed by Western blot analysis. Representative immunoblots are shown. Data represent mean (±SEM). **P < 0.01 (n = 3). (B) Representative fluorescent microscopic images of cellular FITC-albumin uptake in AECs after TGF-β1 (30 min) and subsequent vehicle or GSK3β inhibitor (VPA or tideglusib, additional 30 min) treatment are shown. Scale bars: 50 μm. AECs were exposed to TGF-β or vehicle for 30 minutes and then treated with VPA or tideglusib for an additional 30 minutes. Subsequently, cells were incubated with FITC-albumin for 1 hour, and binding (C), uptake (D), and transepithelial transport (E) of FITC-albumin were measured (n = 5). Data represent mean (±SEM). ***P < 0.001.

Inhibition of GSK3β with VPA or Tideglusib Attenuates ALI in Mice

Orotracheal instillation of bleomycin in mice results in lung injury, which peaks 3–5 days after instillation, and is followed by a resolution phase (9, 33). As the clinical use of VPA is already well established, we first treated 6- to 8-week-old mice with 60 mg/kg (orotracheally) VPA daily starting 2 days before—and continuing 10 days after—the bleomycin challenge. We found that the animals treated with VPA had significantly less BAL protein as well as improved ALI scores and lung function (Figures E7A–E7G). In contrast, intraperitoneal treatment with VPA had no appreciable effect at the concentrations applied (2.5-fold higher than the orotracheal concentration, already causing some level of sedation; Figures E7C–E7G), demonstrating the clear benefit of directly targeting the distal airspaces. Aside from inhibition of GSK3β, VPA is also known to inhibit histone deacetylases (HDACs) (34); however, in our in vitro model, inhibition of HDAC by a potent inhibitor, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, did not affect epithelial albumin clearance (Figure E8).

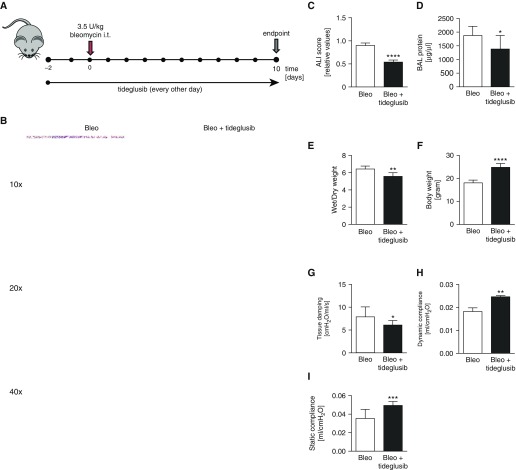

As the protective effects of VPA in ALI might have been mediated, at least in part, by GSK3-independent events, we also applied a novel and specific GSK3β antagonist, tideglusib, in our ALI model (Figure 7A). Importantly, similar to our findings in the VPA-treated animal group, histological analyses of mice treated with tideglusib revealed a significantly decreased severity of lung injury compared with mice treated with bleomycin alone (Figures 7B and 7C). Furthermore, the protein content of the BAL fluid and wet:dry ratio were significantly lower in the animals treated with tideglusib than in the animals treated with bleomycin and vehicle (Figures 7D and 7E). The improved overall state of the animals was also evident by an increased body weight (Figure 7F) in the tideglusib-treated group. Pulmonary compliance was significantly reduced in the bleomycin-treated group, which indicated a decrease in the elasticity of the lung tissue, a characteristic of lung injury. Treatment with tideglusib also significantly improved lung function when compared with bleomycin-treated mice that received vehicle (Figures 7G–7I). Moreover, tideglusib treatment did not affect BAL cell counts or differentials (data not shown), suggesting that the protective effects of tideglusib were independent of recruitment of inflammatory cells upon lung injury.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of GSK3β with tideglusib attenuates ALI in vivo. WT C57BL/6 mice (6- to 8-wk old, 20–25 g) were orotracheally injected with bleomycin (Bleo; 3.5 U/kg in 80 μl of 0.9% saline). Mice were treated 2 days before and for 10 days after bleomycin challenge every other day with either tideglusib (20 mg/kg orotracheally) or vehicle (A). (B) Representative examples of H&E-stained lung tissues from bleomycin-induced ALI in mice treated with vehicle or tideglusib at Day 10 after bleomycin challenge are shown. Scale bars: top row, 100 μm; middle row, 50 μm; bottom row, 20 μm. ALI score (C), BAL protein concentrations (D), lung wet:dry weight ratio (E), body weight (F), and lung mechanics (G–I) comparing bleomycin and vehicle–treated animals with bleomycin and tideglusib–treated mice at Day 10 after bleomycin challenge are depicted. Data represent mean (±SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (n = 7). i.t., intratracheal.

Discussion

Identifying the mechanisms that impair removal of excess protein from the alveolar space is of great clinical importance, as interfering with these events may facilitate the resolution of ARDS. As megalin has been recently identified as a major player in alveolar protein homeostasis, in the present study, we set out to identify the molecular mechanisms regulating the function of this multiligand receptor in the setting of lung injury, aiming to rescue the impaired alveolar protein balance, thereby contributing to repair after ALI. We found that, in AECs, TGF-β treatment reduced the cell-surface abundance of megalin, thus causing decreased uptake of FITC-labeled albumin. The cytoplasmatic domain of megalin contains a PPPSP motif, which represents a GSK3 phosphorylation site and has been revealed to be a major determinant of phosphorylation and subsequent internalization of megalin in vitro (26). This is in line with our findings that saturating GSK3β by expressing a small peptide consisted of a part of the cytoplasmatic domain of megalin containing the PPPSP motif attenuates the TGF-β–induced decrease in albumin binding and uptake in AECs. Furthermore, we demonstrate that activated or constitutively active GSK3β markedly decreases transepithelial albumin transport. Moreover, we found that PP1 dephosphorylates, and thereby activates, GSK3β in AECs, leading to decreased transepithelial protein clearance. In addition, we demonstrate that genetic or pharmacological suppression of PP1 is sufficient to inactivate GSK3β and render transepithelial protein transport unresponsive to TGF-β treatment in primary AECs. As NIPP1 is an important negative regulator of PP1 (35), we demonstrated that silencing of NIPP1 is indeed sufficient to significantly decrease protein binding and uptake by releasing PP1, which in turn activates GSK3β. These effects seem to be unrelated to the transcriptional function of NIPP1, as cells transfected with another NIPP1 variant (forkhead-associated domain), which has a defective transcriptional function, but interacts normally with PP1 (23, 31), exhibit a WT-like behavior. Therefore, we hypothesized that TGF-β has an inhibitory effect on NIPP1 and, thus, increases free PP1; however, the exact nature of TGF-β1–NIPP1 interaction needs further investigation.

Once the megalin-mediated endocytosis of albumin into the AEC was completed, the protein may either be transcytosed or undergo degradation in the cell. We and others have previously shown that, indeed, both of these pathways are involved in the alveolar epithelial removal of proteins, as both application of cellular vesicular transport inhibitors and specific inhibitors of endo- and transcytosis led to albumin retention in the alveolar space (6, 36, 37). However, to what extent each of these pathways individually contributes to the transepithelial clearance of excess protein will require further studies.

As TGF-β is critically involved in both the pathogenesis of ARDS and repair of the lung in patients afflicted with ARDS, the inhibition of TGF-β as a therapeutic option is probably not feasible. Therefore, it appears logical to target the more distal, and thus more specific, downstream elements of specific deleterious signaling patterns in ARDS that are mediated by TGF-β. As most phosphorylation events are reversible, PPs are potentially powerful drug targets; prime examples are the PP2B inhibitors, cyclosporin A and FK506, which are clinically used as potent immunosuppressants (32). However, highly specific cell-permeable inhibitors for the PP1 catalytic subunit are currently not available, and it is doubtful whether such agents could ever be used therapeutically, as they would be likely to inhibit all PP1 holoenzymes (38). Therefore, we focused our efforts on the pharmacologic inhibition of GSK3β. As a first step to investigating whether inhibition of GSK3β could be employed as a therapeutic tool in vivo, we initially tested the effect of clinically feasible GSK3β inhibitors on transepithelial albumin transport in vitro. VPA is a well described, unspecific inhibitor of GSK3β, and is widely used as an antiepileptic drug (39). However, VPA has a fairly narrow therapeutic window, with side effects including central nervous system depression, liver dysfunction, and teratogenicity (40–43). Therefore, we focused on tideglusib, a newly developed GSK3β inhibitor (44) that has recently completed a phase II clinical trial for Alzheimer’s disease and has been approved for compassionate use for supranuclear paralysis by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Tideglusib was found to be very well tolerated, with minimal side effects (45–48). Of note, we find that both tideglusib and VPA result in a robust stabilization of the phosphorylated (inactive) form of GSK3β in AECs and significantly improve transepithelial albumin clearance, even when given after (not only before) TGF-β1 treatment.

Based on our in vitro results, we used a murine model of bleomycin-induced ALI to test the effect of GSK3β inhibition on transepithelial protein transport and, thus, the resolution of lung injury. As VPA has long been clinically established, we first treated mice with orotracheal VPA and found significantly improved protein clearance, resulting in improved pulmonary mechanics and, consequently, decreased severity of lung injury. As a second inhibitor, we again employed the specific GSK3β inhibitor, tideglusib. Mice treated with orotracheal tideglusib also exhibited decreased BAL protein content, indicating improved epithelial protein clearance and, thus, improved lung mechanics and less-severe lung injury. Moreover, animals treated with tideglusib displayed remarkably fewer central nervous system side effects than animals treated with VPA that appeared quite sedated, resulting in decreased food intake and, hence, reduced weight compared with the tideglusib-treated mice. The fact that enhancement of alveolar epithelial protein transport can be accomplished by local application of GSK3β inhibitors makes these inhibitors very attractive for translation in a clinical setting, as local application can be achieved in humans by nebulization of GSK3β inhibitors. We hypothesize that, by using inhaled tideglusib, especially in mechanically ventilated patients, it is very feasible to attain a high degree of epithelial GSK3β inhibition without major systemic side effects. Indeed, we have recently demonstrated therapeutic potential of another inhaled agent, granulocyte/macrophage colony–stimulating factor, in patients with pneumonia-associated severe ARDS (49).

It is important to note that the effects on protein clearance and lung mechanics were comparable between the VPA- and tideglusib-treated animals, as VPA not only inhibits GSK3β, but also HDAC enzymes (50). It has been suggested that the antiinflammatory effects of VPA may be mediated by HDAC inhibition (51). However, as tideglusib does not inhibit HDAC, but acts specifically on GSK3β, our results strongly suggest that the improved resolution of lung injury is indeed an effect of increased protein clearance. This was further confirmed by the fact that, in vitro, HDAC inhibition did not affect either protein binding or uptake.

Importantly, GSK3β has diverse effects in various cell types, and, thus, inhibition of the kinase may affect other molecular pathways that are activated in the setting of ALI. For example, it has been recently shown that GSK3β, by inhibition of the AMP-activated protein kinase, leads to activation of neutrophils and macrophages, thus enhancing the severity of ALI (52, 53). Although we have not investigated the role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the current study, we observed no changes in BAL cell counts or differentials after tideglusib treatment. Moreover, it is well established that GSK3β is an integral part of the Wnt signaling pathway (28); however, suppression of β-catenin did not alter epithelial protein clearance. Finally, we also investigated the potential role of Akt in transepithelial albumin transport, as Akt is a known upstream regulator of GSK3β (14), and found that neither chemical inhibition nor genetic ablation of the kinase influenced protein transit, suggesting that neither signaling pathway was required for the down-regulation of albumin transport upon TGF-β exposure.

Importantly, the molecular mechanisms described here may also be at play in other injured absorbing epithelia, such as those of the kidney and the gastrointestinal tract, and in the blood–brain barrier. For example, diabetic nephropathy, a condition that is characterized by significant proteinuria, is well known to be mediated by TGF-β (54). Moreover, in the kidney, megalin also serves as the primary plasma protein receptor responsible for the proximal tubular uptake of proteins under normal conditions (55). Thus, it is plausible that the protein loss observed in diabetic nephropathy is at least in part due to the above-described TGF-β–induced and GSK3β-mediated down-regulation of megalin cell-surface stability in the proximal tubules. In addition, aside from protein uptake, megalin function has also been associated with vitamin and cholesterol transport processes in the gastrointestinal tract (56, 57). Furthermore, megalin-mediated transcytosis of amyloid-β peptide across the blood–brain barrier has been shown to play a central role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (58). Thus, the TGF-β– and/or GSK3β-megalin axis may also be involved in vitamin and cholesterol homeostasis and cognitive function.

Our studies are limited by three important aspects, which will need further attention. First, the bulk of our current in vitro studies were performed in ATII cells. However, ATI cells cover a larger area of the alveolar surface. In a previous study, we have shown that monolayers of ATI-like cells differentiated from ATII cells also express megalin and show megalin-mediated albumin transport velocity comparable to ATII cells (6). As cell surface stability of megalin is universally regulated by the GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of the PPPSP domain of the receptor (26), it is highly plausible that the signaling pathway we describe in ATII cells will be identical in ATI cells. Second, although we demonstrate increased alveolar protein retention in megalin+/− animals when compared with WT littermates after bleomycin challenge, the exact contribution of megalin to the overall protein clearance rate in this ALI model has not been determined. Future studies are warranted to precisely measure albumin transport rates in vivo in megalin+/− mice or ATII and/or ATI cell–specific megalin knockout animals. Finally, more data regarding pharmacokinetics of alveolar deposition and side effects are needed before initiation of clinical trials with the novel GSK3β inhibitor, tideglusib. To date, two phase II clinical trials have been published with this novel drug, both of which found tideglusib safe, with only minor and reversible side effects, even when administered systemically (47, 48).

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, we describe, for the first time, a unique TGF-β–triggered pathway, which, via NIPP1, PP1, and GSK3β, negatively regulates megalin, the major mediator of alveolar protein clearance (Figures 8A and 8B). Inhibiting alveolar epithelial GSK3β is an intriguing, novel approach to ARDS therapy, as it directly targets one of the major underlying pathomechanisms of the disease.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the mechanisms of impaired alveolar protein clearance in ALI and potential means of rescue. In ALI, enhanced alveolar concentrations of TGF-β impair megalin-mediated alveolar albumin clearance, resulting in persistence of the protein-rich alveolar edema, which further promotes the pathomechanistic sequel of ALI. The underlying signaling cascade includes the release of NIPP1 from PP1, thereby activating the phosphatase, which, in turn, dephosphorylates GSK3β at Ser-9, leading to activation of the kinase. Activated GSK3β phosphorylates the albumin receptor, megalin, at the C-terminal PPPSP domain and promotes internalization of the receptor, and thus loss of albumin clearance. In contrast, interference with PP1 (siRNA or calyculin) or GSK3β (siRNA or the clinically relevant pharmacological agents VPA or tideglusib) prevents megalin phosphorylation and re-establishes alveolar transepithelial protein clearance, thus promoting ALI resolution. ATI, alveolar epithelial type I cell; ATII, alveolar epithelial type II cell.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank T. E. Willnow, Ph.D., (Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany) for his generous gift of the megalin knockout mice and M. Bollen, Ph.D., (Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium) for the nuclear inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1–forkhead-associated domain mutant and helpful discussions of the data and Miriam Wessendorf (Universities of Giessen and Marburg Lung Center, Giessen, Germany) and Uta Eule (Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim, Germany) for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the Excellence Cluster “Cardio Pulmonary System” (ECCPS), the German Center for Lung Research, the Landes-Offensive zur Entwicklung Wissenschaftlich-ökonomischer Exzellenz of the Hessen State Ministry of Higher Education, Research and the Arts and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Clinical Research Unit KFO309/1) (K.M., R.E.M., S.H., W.S., S.S.P., and I.V.), and by an ECCPS Clinical Scientist Career Program grant (I.V.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design of the experiments—I.V., C.U.V., S.S.P., and W.S.; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data—C.U.V., S.S.P., Y.B., H.M.A.-T., L.C.M., H.K.E., K.M., R.E.M., S.H., and I.V.; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content—C.U.V., S.S.P., R.E.M., W.S., and I.V.; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2731–2740. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herold S, Gabrielli NM, Vadász I. Novel concepts of acute lung injury and alveolar–capillary barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L665–L681. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00232.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hastings RH, Folkesson HG, Matthay MA. Mechanisms of alveolar protein clearance in the intact lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L679–L689. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00205.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou G, Dada LA, Sznajder JI. Regulation of alveolar epithelial function by hypoxia. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:1107–1113. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00155507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachofen M, Weibel ER. Alterations of the gas exchange apparatus in adult respiratory insufficiency associated with septicemia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;116:589–615. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.116.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchäckert Y, Rummel S, Vohwinkel CU, Gabrielli NM, Grzesik BA, Mayer K, Herold S, Morty RE, Seeger W, Vadász I. Megalin mediates transepithelial albumin clearance from the alveolar space of intact rabbit lungs. J Physiol. 2012;590:5167–5181. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.233403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grzesik BA, Vohwinkel CU, Morty RE, Mayer K, Herold S, Seeger W, Vadász I. Efficient gene delivery to primary alveolar epithelial cells by nucleofection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L786–L794. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00191.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fahy RJ, Lichtenberger F, McKeegan CB, Nuovo GJ, Marsh CB, Wewers MD. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: a role for transforming growth factor-β1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:499–503. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0092OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters DM, Vadász I, Wujak L, Wygrecka M, Olschewski A, Becker C, Herold S, Papp R, Mayer K, Rummel S, et al. TGF-β directs trafficking of the epithelial sodium channel ENaC which has implications for ion and fluid transport in acute lung injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E374–E383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306798111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittet JF, Griffiths MJ, Geiser T, Kaminski N, Dalton SL, Huang X, Brown LA, Gotwals PJ, Koteliansky VE, Matthay MA, et al. TGF-β is a critical mediator of acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1537–1544. doi: 10.1172/JCI11963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budinger GR, Chandel NS, Donnelly HK, Eisenbart J, Oberoi M, Jain M. Active transforming growth factor-β1 activates the procollagen I promoter in patients with acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:121–128. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2503-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen P, Frame S. The renaissance of GSK3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:769–776. doi: 10.1038/35096075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1175–1186. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frame S, Cohen P. GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem J. 2001;359:1–16. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodgett JR. Physiological roles of glycogen synthase kinase-3: potential as a therapeutic target for diabetes and other disorders. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2003;3:281–290. doi: 10.2174/1568008033340153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rayasam GV, Tulasi VK, Sodhi R, Davis JA, Ray A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3: more than a namesake. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:885–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sklepkiewicz P, Schermuly RT, Tian X, Ghofrani HA, Weissmann N, Sedding D, Kashour T, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Pullamsetti SS. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β contributes to proliferation of arterial smooth muscle cells in pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wada A. GSK-3 inhibitors and insulin receptor signaling in health, disease, and therapeutics. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009;14:1558–1570. doi: 10.2741/3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alejandre-Alcázar MA, Kwapiszewska G, Reiss I, Amarie OV, Marsh LM, Sevilla-Pérez J, Wygrecka M, Eul B, Köbrich S, Hesse M, et al. Hyperoxia modulates TGF-β/BMP signaling in a mouse model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L537–L549. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00050.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pullamsetti SS, Savai R, Dumitrascu R, Dahal BK, Wilhelm J, Konigshoff M, Zakrzewicz D, Ghofrani HA, Weissmann N, Eickelberg O, et al. The role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:87ra53. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vadász I, Dada LA, Briva A, Trejo HE, Welch LC, Chen J, Tóth PT, Lecuona E, Witters LA, Schumacker PT, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates CO2-induced alveolar epithelial dysfunction in rats and human cells by promoting Na,K-ATPase endocytosis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:752–762. doi: 10.1172/JCI29723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boudrez A, Beullens M, Groenen P, Van Eynde A, Vulsteke V, Jagiello I, Murray M, Krainer AR, Stalmans W, Bollen M. NIPP1-mediated interaction of protein phosphatase-1 with CDC5L, a regulator of pre-mRNA splicing and mitotic entry. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25411–25417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willnow TE, Hilpert J, Armstrong SA, Rohlmann A, Hammer RE, Burns DK, Herz J. Defective forebrain development in mice lacking gp330/megalin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8460–8464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takano M, Kawami M, Aoki A, Yumoto R. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of macromolecules and strategy to enhance their transport in alveolar epithelial cells. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12:813–825. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.992778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuseff MI, Farfan P, Bu G, Marzolo MP. A cytoplasmic PPPSP motif determines megalin’s phosphorylation and regulates receptor’s recycling and surface expression. Traffic. 2007;8:1215–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes K, Nikolakaki E, Plyte SE, Totty NF, Woodgett JR. Modulation of the glycogen synthase kinase-3 family by tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1993;12:803–808. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu D, Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernández F, Langa E, Cuadros R, Avila J, Villanueva N. Regulation of GSK3 isoforms by phosphatases PP1 and PP2A. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;344:211–215. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar A, Pandurangan AK, Lu F, Fyrst H, Zhang M, Byun HS, Bittman R, Saba JD. Chemopreventive sphingadienes downregulate Wnt signaling via a PP2A/Akt/GSK3β pathway in colon cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1726–1735. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beullens M, Vulsteke V, Van Eynde A, Jagiello I, Stalmans W, Bollen M. The C-terminus of NIPP1 (nuclear inhibitor of protein phosphatase-1) contains a novel binding site for protein phosphatase-1 that is controlled by tyrosine phosphorylation and RNA binding. Biochem J. 2000;352:651–658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bollen M, Peti W, Ragusa MJ, Beullens M. The extended PP1 toolkit: designed to create specificity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L379–L399. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao L, Chen CN, Hajji N, Oliver E, Cotroneo E, Wharton J, Wang D, Li M, McKinsey TA, Stenmark KR, et al. Histone deacetylation inhibition in pulmonary hypertension: therapeutic potential of valproic acid and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. Circulation. 2012;126:455–467. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.103176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ceulemans H, Bollen M. Functional diversity of protein phosphatase-1, a cellular economizer and reset button. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1–39. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yumoto R, Nishikawa H, Okamoto M, Katayama H, Nagai J, Takano M. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis of FITC-albumin in alveolar type II epithelial cell line RLE-6TN. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L946–L955. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00173.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yumoto R, Suzuka S, Oda K, Nagai J, Takano M. Endocytic uptake of FITC-albumin by human alveolar epithelial cell line A549. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2012;27:336–343. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-11-rg-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Sleeman JE, Lamond AI. Dynamic targeting of protein phosphatase 1 within the nuclei of living mammalian cells. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4219–4228. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.23.4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Činčárová L, Zdráhal Z, Fajkus J. New perspectives of valproic acid in clinical practice. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22:1535–1547. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.853037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vermeulen J, Aldenkamp AP. Cognitive side-effects of chronic antiepileptic drug treatment: a review of 25 years of research. Epilepsy Res. 1995;22:65–95. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(95)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dreifuss FE, Langer DH. Side effects of valproate. Am J Med. 1988;84:34–41. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roullet FI, Lai JK, Foster JA. In utero exposure to valproic acid and autism—a current review of clinical and animal studies. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2013;36:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johannessen CU, Johannessen SI. Valproate: past, present, and future. CNS Drug Rev. 2003;9:199–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2003.tb00249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luna-Medina R, Cortes-Canteli M, Sanchez-Galiano S, Morales-Garcia JA, Martinez A, Santos A, Perez-Castillo A. NP031112, a thiadiazolidinone compound, prevents inflammation and neurodegeneration under excitotoxic conditions: potential therapeutic role in brain disorders. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5766–5776. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1004-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.del Ser T, Steinwachs KC, Gertz HJ, Andrés MV, Gómez-Carrillo B, Medina M, Vericat JA, Redondo P, Fleet D, León T. Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease with the GSK-3 inhibitor tideglusib: a pilot study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:205–215. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Höglinger GU, Huppertz HJ, Wagenpfeil S, Andrés MV, Belloch V, León T, Del Ser T TAUROS MRI Investigators. Tideglusib reduces progression of brain atrophy in progressive supranuclear palsy in a randomized trial. Mov Disord. 2014;29:479–487. doi: 10.1002/mds.25815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tolosa E, Litvan I, Höglinger GU, Burn D, Lees A, Andrés MV, Gómez-Carrillo B, León T, Del Ser T TAUROS Investigators. A phase 2 trial of the GSK-3 inhibitor tideglusib in progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord. 2014;29:470–478. doi: 10.1002/mds.25824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lovestone S, Boada M, Dubois B, Hull M, Rinne JO, Huppertz HJ, Calero M, Andres MV, Gomez-Carrillo B, Leon T, Del Ser T. A phase II trial of tideglusib in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;45:75–88. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herold S, Hoegner K, Vadász I, Gessler T, Wilhelm J, Mayer K, Morty RE, Walmrath HD, Seeger W, Lohmeyer J. Inhaled granulocyte/macrophage colony–stimulating factor as treatment of pneumonia-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:609–611. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-2041LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Göttlicher M, Minucci S, Zhu P, Krämer OH, Schimpf A, Giavara S, Sleeman JP, Lo Coco F, Nervi C, Pelicci PG, et al. Valproic acid defines a novel class of HDAC inhibitors inducing differentiation of transformed cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:6969–6978. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ji MH, Li GM, Jia M, Zhu SH, Gao DP, Fan YX, Wu J, Yang JJ. Valproic acid attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Inflammation. 2013;36:1453–1459. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9686-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Z, Bone N, Jiang S, Park DW, Tadie JM, Deshane J, Rodriguez CA, Pittet JF, Abraham E, Zmijewski JW. AMP-activated protein kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3β modulate the severity of sepsis-induced lung injury. Mol Med. 2015;21:937–950. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2015.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park DW, Jiang S, Liu Y, Siegal GP, Inoki K, Abraham E, Zmijewski JW. GSK3β-dependent inhibition of AMPK potentiates activation of neutrophils and macrophages and enhances severity of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307:L735–L745. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00165.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hathaway CK, Gasim AM, Grant R, Chang AS, Kim HS, Madden VJ, Bagnell CR, Jr, Jennette JC, Smithies O, Kakoki M. Low TGFβ1 expression prevents and high expression exacerbates diabetic nephropathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:5815–5820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504777112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nielsen R, Christensen EI, Birn H. Megalin and cubilin in proximal tubule protein reabsorption: from experimental models to human disease. Kidney Int. 2016;89:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christensen EI, Nielsen R, Birn H. From bowel to kidneys: the role of cubilin in physiology and disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:274–281. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marzolo MP, Farfán P. New insights into the roles of megalin/LRP2 and the regulation of its functional expression. Biol Res. 2011;44:89–105. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602011000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharma HS, Castellani RJ, Smith MA, Sharma A. The blood–brain barrier in Alzheimer’s disease: novel therapeutic targets and nanodrug delivery. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2012;102:47–90. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386986-9.00003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]