Abstract

Heterotropic interactions between atorvastatin (ARVS) and dronedarone (DND) have been deciphered using global analysis of the results of binding and turnover experiments for pure drugs and their mixtures. The in vivo presence of atorvastatin lactone (ARVL) was explicitly taken into account by using pure ARVL in analogous experiments. Both ARVL and ARVS inhibit DND binding and metabolism, while significantly higher affinity of CYP3A4 towards ARVL makes the latter the main effector in this system. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal significantly different modes of interactions of DND and ARVL with the substrate binding pocket and with the peripheral allosteric site. Interactions of both substrates with residues F213 and F219 at the allosteric site play the most important role in the communication of conformational changes induced by effector binding towards productive binding of substrate at the catalytic site.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Drug metabolizing human cytochromes P450 represent a very unusual group of enzymes because of their extremely broad substrate specificity, which allows them to metabolize hundreds of chemically diverse compounds, while simultaneously binding two or three substrate molecules. This is especially true for CYP3A4, as well as for several other isoforms, such as CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2A6, and CYP1A2. CYP3A4 is involved in metabolism of more than 40% drugs currently on the market, and as such constitutes a major site of drug-drug interactions. These interactions are manifested as inhibition or activation of metabolism of one drug in the presence of another, and sometimes can result in dangerous physiological reactions. Hence, mechanistic understanding of drug-drug interactions mediated my cytochromes P450 and CYP3A4 in particular is important for the controlled prescribing of multiple drugs and avoiding potentially deleterious combinations.

Recently heterotropic allosteric activation of multiple human cytochromes P450 has been documented in model reconstituted systems (1–3), liver microsomes (4), whole cell metabolism (5) and animal models (2). Critically important for all these observations is the presence of a lipid bilayer, with no activation detected in control experiments without lipids (2, 3). Currently there is no x-ray structure of a cytochrome P450 in a membrane bilayer to serve as a guide as to the role of the membrane interface in controlling activity. Hence we obtain the details of effector binding at the protein-membrane interface through combination of biophysical and biochemical experimental methods together with molecular dynamics calculations. The observed effect depends on both substrates, i.e. heteroactivation is substrate-dependent (6). This was known on the phenomenological level, but the mechanism of this activation is not completely understood. The role of structural and dynamic changes in P450 molecule caused by effector binding and due to oligomerization of P450 enzymes and redox partners in the membrane are actively debated in the recent literature (1, 7–16). Much information on CYP3A4 is available from point mutation studies and their effect on homotropic and heterotropic cooperativity.(17–19) Several structural models explaining cooperative effects of multiple substrate binding in CYP3A4 have been suggested based on functional studies.(20–22) (23–26) (27–29) However, prediction of drug-drug interactions mediated by cytochromes P450 is still not feasible at the present time. Detailed experimental studies are needed on heterotropic activation of monomeric CYP3A4 in the membrane in order to evaluate the allosteric mechanism in one P450 molecule and to get a better insight into the possible role of oligomerization.

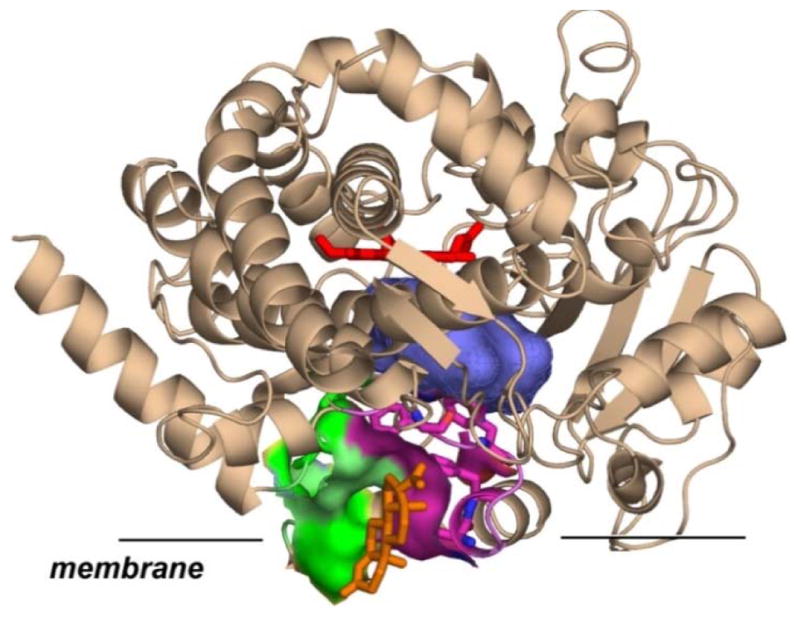

In previous work (1) we described interactions between two substrates in monomeric CYP3A4, using the detailed site-specific mechanism and proposed structural explanation of the observed effect (competitive or non-competitive, activation or inhibition) for the given pair of drugs progesterone and carbamazepine and their preferential binding to the allosteric or productive site (see Figure 1 and legend).

Figure 1.

Schematic model of cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 inserted in the membrane. CYP3A4 structure with progesterone (orange sticks) bound at the peripheral site (pdb file 1W0F (30)) is shown in cartoon representation with heme shown in red sticks, Membrane insertion is schematically drawn according to MD simulations ((1, 31)). Amino acids of F-F′ (magenta) and G-G′ (green) loops in direct contact with progesterone are highlighted as surfaces. Substrate binding cavity near catalytic site is shown as blue surface.

Our results indicate that the allosteric site in CYP3A4 is located at the protein-membrane interface, where the F′-G′ helices are in direct contact with the lipid head groups or partially embedded into the lipid bilayer (1). Binding of an effector molecule at this site restricts the mobility of F′-G′ helices and dynamically stabilizes oxy-complex and bound substrate (32, 33). In addition, conformational changes of the protein caused by interactions with an effector modify the shape and volume of the substrate binding pocket and thus perturb the metabolism of substrates, resulting in activation or in changes of regio-specificity of metabolism (1). All currently available experimental results on heterotropic activation of human cytochromes P450 suggest a specific allosteric response to steroids and other effectors having similar molecular properties, i.e. flat hydrophobic molecules (1, 34, 35). However, little is known about ability of other classes of substrates to interact with the same allosteric site and about possible effects of such interactions on the metabolism of clinically relevant substrates.

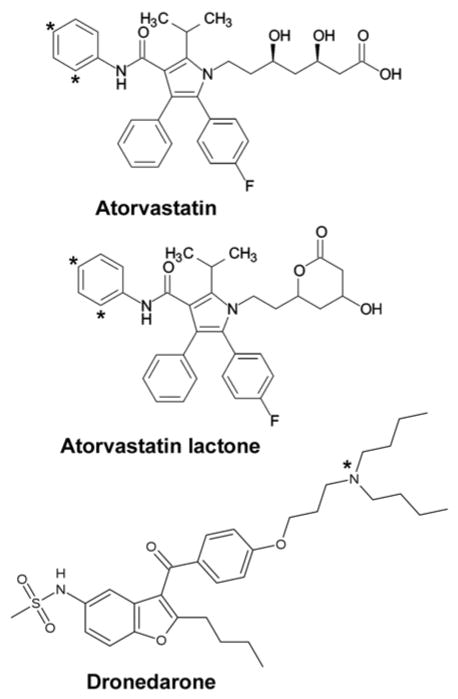

In order to extend this previously developed approach to pharmacologically important systems, we used a combination of experimental and theoretical methods for a detailed investigation of the metabolism of two drugs, Atorvastatin (a cholesterol lowering drug, Lipitor®) and Dronedarone (an antiarrythmic drug, Multaq®) which are involved in the drug-drug interactions mediated by CYP3A4 (36–39). Both drugs are metabolized by CYP3A4 (37, 40–44) as shown in Figure 1, and both are involved in drug-drug interactions (36–39, 41). Importantly, the highly lever-aged effects of Multaq interactions with multiple cardiac ion channels(45) make interaction with other commonly prescribed medications, such as Lipitor, extremely relevant. In order to understand the mechanism of CYP3A4 metabolism of these compounds, we measured the rates of steady-state metabolism of both drugs separately and in mixtures. In addition, we included in this study atorvastatin lactone, which exists in equilibrium with the acidic active form of atorvastatin, and binds to CYP3A4 much tighter (46). In order to obtain structural information on possible preferential binding of these substrates to CYP3A4 we performed a series of molecular dynamics simulations of CYP3A4 in the lipid bilayer, with one or two substrates molecules bound in various configurations. Such a combination of experimental and theoretical methods applied to the analysis of heterotropic activation of CBZ epoxidation in the presence of PGS suggested a structural explanation of the general allosteric properties of CYP3A4 and identified Phe213 and Phe215 as critical residues involved in allosteric regulation (1). In the current study we probed the importance of these and other nearby residues for binding and activity regulation with substrates of different type and revealed overall similarity in CYP3A4 structural changes and regulation with several important variations.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

Expression and purification of membrane scaffold protein (MSP), cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 and rat P450 reductase, as well as preparation of CYP3A4 in POPC Nanodiscs (ND) was performed as described (32, 33, 47). Cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 was expressed from the NF-14 construct in the PCWori+ vector with a C-terminal pentahistidine tag generously provided by Dr. F. P. Guengerich (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN). Cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) was expressed using the rat CPR/pOR262 plasmid, a generous gift from Dr. Todd D. Porter (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY). Incorporation of CPR into preformed and purified CYP3A4-Nanodiscs was made by direct addition of CPR at 1:4 CYP3A4/CPR molar ratio, as described (48). All experiments were performed at 37° C using the POPC Nanodisc system similar to our earlier studies (34, 35), in order to allow direct comparison of results. This reconstitution system provides a stable, well characterized and monodisperse preparation of CYP3A4 incorporated into the model lipid bilayer effectively mimicking the native membrane.

UV-Vis spectroscopy

Substrate titration experiments were performed using solutions of 1 – 2 μM CYP3A4 in Nano-discs in a Cary 300 spectrophotometer (Varian, Lake Forest, CA) at 37˚C. For the mixed titration experiments the mixtures of atorvastatin (ARVS) or atorvastatin lactone (ARVL) with dronedarone (DND) in methanol were prepared and added to the CYP3A4-Nanodisc solution, thereby maintaining the constant substrate ratios. The final concentration of methanol was less than 1.5%.

NADPH oxidation and product formation

CYP3A4 incorporated Nanodiscs with CPR as described (48) with added substrates were preincubated for 5 minutes at 37˚C, in a 1 ml reaction volume in 100 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol. The concentration of CYP3A4 was in the range from 60 to 100 nM. The reaction was initiated with the addition of 200 nmol of NADPH. NADPH consumption was monitored for 5 min and calculated from the absorption changes at 340 nm using the extinction coefficient 6.22 mM−1 cm−1.

Reactions for product analysis were performed under similar conditions. At the end of the incubation period, 0.2 ml aliquots were quenched with 1.6 ml of 2:1 mixture of acetonitrile/methanol supplemented with the internal standard mevastatine, and dried. The samples were dissolved in 100 μl of methanol and 30 ul was injected onto Ace 3 C18 HPLC column, 2.1 × 150 mm (MAC-MOD Analytical, Chadds Ford, PA). The mobile phase contained 15% acetonitrile and 15% methanol in water; products were separated in linear gradient of acetonitrile and methanol rising from 15% to 37% each over 35 min at flow rate 0.2 ml/min. The calibration and method validation was performed using commercially available metabolites of DND and ARVS. The chromatograms were processed with Millennium software (Waters).

Global analysis for deconvoluting apparent cooperative effects in P450

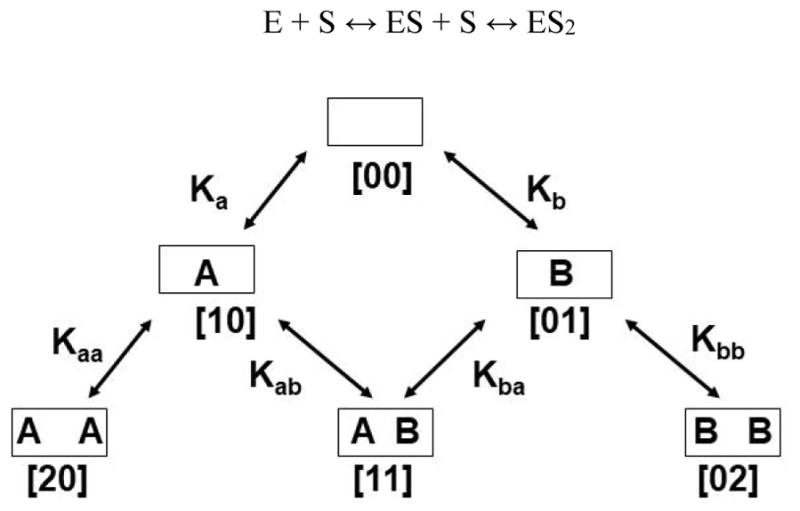

Global analysis of homotropic cooperativity for metabolism of one substrate was performed, as previously described (34), by simultaneously fitting the experimental data sets to the three state linear equilibrium binding scheme:

Here E is the concentration of substrate-free CYP3A4 (designated [00] in Scheme 1), S is the concentration of the free substrate, and ESi are the concentrations of the binding intermediates, i.e., complexes of CYP3A4 with i molecules of substrate bound (i = 0,1, 2). These binding intermediates are designated as [10] and [20] for one substrate, and [01], [02] for the second one (Scheme 1), with stoichiometric macroscopic dissociation constants Ka, Kaa for substrate A and Kb, Kbb for substrate B. Binding of up to three molecules of smaller substrates to one CYP3A4 monomer was described in previous studies (22, 26, 49), however, with the substrates used in the current study data could be successfully fitted with only two binding sites.

Scheme 1.

The fractions of the enzyme-substrate complexes were expressed using the standard binding polynomials (50),

with the functional properties at different substrate concentrations represented as the linear combination of the fractional contributions from binding intermediates. For example, the fraction of the high-spin CYP3A4 in Type I titrations, YS, is calculated as the weighted sum of the signals from the cytochrome P450 molecules with 0, 1, or 2 substrate molecules bound, having a0, a1, and a2 fractions of high-spin state:

The set of such equations for the spectral titration, NADPH consumption, and product formation have been used for the simultaneous fitting of the experimental data obtained under the same conditions, using the same set of dissociation constants, which then corresponds to a total of twelve parameters. The fitting program was written in MATLAB using the Nelder-Mead simplex minimization algorithm implemented in the MATLAB subroutine “fminsearch.m.”

Heterotropic interactions were analyzed using the system of stoichiometric equilibria shown in the Scheme 1. A complete description of six states with different combinations of two substrates which can bind at two binding site requires six binding constants, although only five of them are independent variables (Scheme 1 and legend). The functional properties of these binding intermediates cannot be individually measured for the pure states with exception of [00] and possibly [20] and [02], if substrate saturation can be reached. However, the six-state system can be efficiently separated into three parts by the choice of experimental conditions. The homotropic pathways [00] → [10] → [20] and [00] → [01] → [02] can be measured separately with only one substrate, as described above and in our previous publications (1, 35). Subsequently, the full sets of obtained parameters can be used for the experiments with the mixture of two substrates, if all experiments are performed under identical conditions. In this case only one equilibrium dissociation constant K11, and other functional properties for the only mixed intermediate [11], need to be resolved from the similar set of experiments, with the number of unknown parameters the same as for the homotropic problem, and can be successfully treated using global analysis (34, 35, 51). This was done using the same approach as outlined above for the global analysis of homotropic experiments.

Computational Procedures

CYP3A4 model and initial configurations

A membrane-bound model of the globular domain of CYP3A4 (PDB entry 1TQN (52)), including the transmembrane helix formed by residues 1 to 27, was adopted from the last frame of one of the membrane binding simulations reported previously (53). The system is composed of CYP3A4 bound to a solvated POPC membrane. This system was then minimized for 1000 steps and equilibrated for 100 ps while restraining the heavy atoms of the protein and the lipids within 3.5 Å of the protein with a force constant k = 1 kcal mol−1 Å−2. Following this step, the system was simulated without restraints for 100 ns.

Modeling and simulation of membrane-bound CYP3A4 with ARVL and DND

Initial structural models of membrane-bound CYP3A4 bound to ARVL and DND were generated with molecular docking performed with AutoDock Vina (54). We started by docking a single copy of ARVL or DND to our previously derived model of membrane-bound CYP3A4 (53). For this first docking step, we focused on the binding sites characterized in our previous work, i.e. the productive site and the allosteric site located at the protein-membrane interface (1). The resulting docked poses of ARVL and DND were then clustered based on the RMSD of their heavy atoms and distance of sites of metabolism (as shown in Figure 1) to the heme iron for docking in the productive site. Finally, the configurations of CYP3A4 with either ARVL or DND bound in the productive or allosteric site with the best docking score were selected as a starting point for MD simulations of a single drug bound to CYP3A4. The resulting systems had dimensions 100Å×100Å×115Å, with ~107,000 atoms.

For docking of a second drug molecule, the CYP3A4-drug complexes obtained from the MD simulations of either DND or ARVL in the allosteric site generated in the previous step were then employed as receptor structures for a second molecular docking step with Autodock Vina (54). The docking of the second molecule (ARVL or DND) focused on the productive site, since the goal was to capture the effect of a drug bound at this site on the ability of CYP3A4 to accommodate another drug in the productive site cavity. The resulting docked poses from this second docking were clustered as described in the previous step. After the second docking step, structural models of membrane-bound CYP3A4 in complex with two drug molecules (ARVL/DND, DND/DND, or ARVL/ARVL) in the productive and allosteric site were obtained, and employed as starting points for MD simulations. These systems had dimensions 100Å×100Å×115Å, with ~107,000 atoms.

As a control, we also performed simulations of CYP3A4 with ARVL or DND in a water box without the membrane. Initial structures for these simulations were generated by removing the lipid bilayer and the transmembrane helix of CYP3A4 (residues 1 to 27) from the systems with a drug in the allosteric site. The resulting structures were then solvated with the “solvate” plugin from VMD (55), and Na+ and Cl− ions where added to neutralize the system, with a net concentration of 100 mM. The two resulting systems had dimensions 100Å×100Å×100Å, and 92,000 atoms. These simulations were conducted in order to assess the role of the membrane in drug binding at the allosteric site (located at the protein-membrane interface).

Each simulation system was minimized for 2,000 steps, and equilibrated for 1 ns with the Cα of CYP3A4 and the heavy atoms of the ligands (ARVL or DND) harmonically restrained (with force constant k=1 kcal/mol/Å2). Following this preparation step, 100 ns production simulations were performed for each system. A summary of all the MD simulations performed is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of CYP3A4 simulations. All systems were simulated for 100 ns

| System | Productive Site | Allosteric site | Membrane |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ARVL | - | Yes |

| 2 | DND | - | Yes |

| 3 | - | ARVL | Yes |

| 4 | - | DND | Yes |

| 5 | - | ARVL | No |

| 6 | - | DND | No |

| 7 | ARVL | ARVL | Yes |

| 8 | ARVL | DND | Yes |

| 9 | DND | ARVL | Yes |

| 10 | DND | DND | Yes |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Conditions and Protocol

The simulations were performed using NAMD2 (56). The CHARMM27 force field with cMAP (57, 58)corrections was used for the protein and the CHARMM36 (59, 60) force field was used for lipids. Parameters for ARVL and DND were obtained by analogy from the CHARMM General Force Field (61), and further refined using the Force Field Toolkit implemented in VMD (62). The TIP3P model was used for water (63). Simulations were performed with the NPT ensemble with a time step of 2 fs. A constant pressure of 1 atm was maintained using the Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston method (64, 65). Temperature was maintained at 310 K using Langevin dynamics with a damping coefficient γ of 0.5 ps−1 applied to all atoms. Non-bonded interactions were cut off at 12 Å, with smoothing applied after 10 Å. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) method (66) was used for long-range electrostatic calculations with a grid density greater than 1 Å−3.

Results

In order to evaluate the relative importance of ARVS and ARVL effect on the CYP3A4 metabolism of DND in the mixtures, we started by measuring the metabolism of all three compounds as pure substrates individually. This was accomplished using global analysis approach developed previously in our studies of CYP3A4 homotropic cooperativity using testosterone as a substrate (16, 34). Spectral titration data, the steady-state rates of NADPH consumption, and the rates of substrate metabolism were measured under identical conditions and analyzed simultaneously using the same set of stoichiometric substrate binding constants as described (1, 34, 35). In this case, we used a two-site model for analysis of all experiments with substrates used in this work, because of larger sizes of ARVS, ARVL and DND allowing binding of only one molecule in the active site of CYP3A4. Results of analysis (Table 2) confirm that all experimental data can be described with this two-site model, which is not the case for CYP3A4 with steroid substrates (1, 34, 35).

Table 2.

Parameters of metabolism of atorvastatin, atorvastatin lactone and dronedarone by CYP3A4 in Nanodiscs.

| Substrate, number bound and Ki, uM | NADPH, min−1 | Product, min−1 | Fe3+ Spin shift, % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| ARVS 0 | 37 | 0 | 12 |

| 1 108 [95 – 150] | 242 [227 – 292] | 17 [15.6 – 21.5] | 26 [23 – 29] |

| 2 130 [56 – 215] | 108 [86 – 122] | 2.2 [0.2 – 3.9] | 28 [26 – 30] |

|

| |||

| ARVL 0 | 44 | 0 | 14 |

| 1 1 [0.83 – 1.15] | 202 [193 – 211] | 13 [9.6 – 14.7] | 22 [16 – 26] |

| 2 22 [12 – 41] | 141 [119 – 155] | 41 [35 – 50] | 62 [56 – 72] |

|

| |||

| DND 0 | 39 | 0 | 13 |

| 1 0.15 [0.02 – 0.32] | 51 [46 – 58] | 2.5 [1.6 – 3.4] | 14 [5 – 20] |

| 2 3.6 [2.8 – 4.5] | 92 [91 – 93] | 8.2 [8.1 – 8.3] | 78 [76 – 79] |

Metabolism of atorvastatin

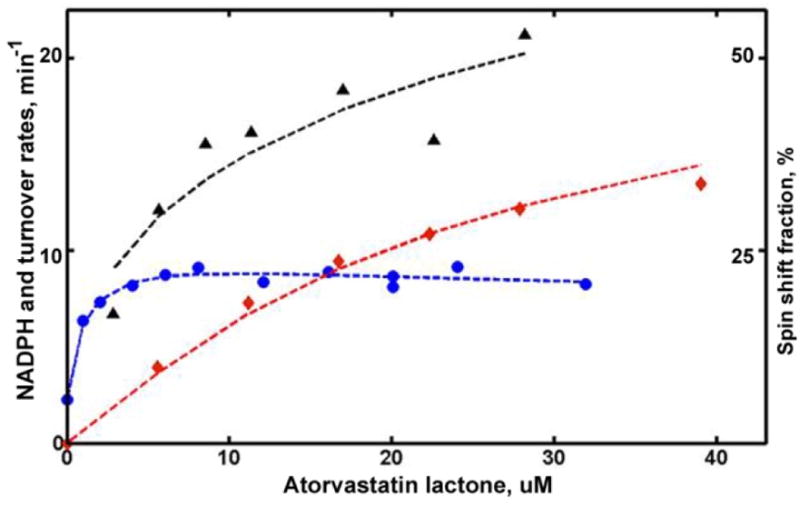

Global analysis of ARVS metabolism reveals that ARVS is metabolized faster when only one substrate is bound with a dissociation constant of Kd1 = 108 μM. (Table 2) The second binding event (Kd2 = 130 μM) results in significant inhibition and slower NADPH consumption, observed at high concentrations of substrate (Figure 2). The binding of ARVS does not produce significant shift of the spin sate equilibrium, raising the fraction of high spin to only 28%.

Figure 2.

Structures of substrates ARVS and DND with the main sites of metabolism in CYP3A4 indicated with asterisks.

These results suggest a more favorable binding of ARVS to the productive site than to the peripheral non-productive site. Inhibition at high concentrations of ARVS is likely due to slower product release, which may be blocked by the second ARVS molecule, as was suggested earlier for CYP2E1 (67, 68), or to a perturbation of binding and/or catalytic properties at the active site caused by the presence of ARVS at the peripheral site. Slower NADPH consumption at high ARVS concentrations favors the first suggestion, while the latter hypothesis is less likely, as the spin state equilibrium is not perturbed by the second binding event.

Metabolism of atorvastatin lactone

CYP3A4 spectral titration with ARVL reveals tighter binding and higher spin shift, as compared to the same experiments with ARVS. Interestingly, binding of the second ARVL molecule significantly improves spin shift and accelerates catalysis.

Global analysis of turnover results performed using the two-site model, shows that the first binding of ARVL happens with much higher affinity (Kd1 = 1 μM), but with relatively small increase of the high-spin fraction, from 14% to 22%. The second binding requires significantly higher concentration of ARVL (Kd2 = 22 μM) and results in higher spin shift (up to 62%). (Figure S1, titration) Consistent with this, the turnover rate increases by a factor of three (from 13 to 41 min−1) with the binding of second substrate molecule. The slower NADPH oxidation rate at high ARVL concentrations is most probably due to the slower product dissociation rate, when the peripheral site is also occupied by the second substrate molecule. (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Global analysis of CYP3A4 metabolism of ARVL. Symbols are the same as in Figure 3. Rate of NADPH consumption is scaled by a factor of 20 to match the plot limit.

Metabolism of dronedarone

Analysis of DND turnover (Figure 5) shows that metabolism of DND is faster when two substrate molecules are bound. The first binding is tight (Kd1 = 0.15 μM), but does not produce any shift in the spin state equilibrium. This is analogous to TST, ANF and PGS binding seen in CYP3A4,(1, 34, 35) however, unlike steroids, the first DND binding event is productive. The binding of the second DND molecule, which happens with much lower affinity (Kd2 = 3.6 μM), significantly increases the spin shift and coupling. (Table 2) Overall, these results are qualitatively similar to the metabolism of ARVL, but different from the features observed with ARVS as a substrate.

Figure 5.

Global analysis of CYP3A4 metabolism of DND. Symbols are the same as in Figure 3 and 4. Rate of NADPH consumption is scaled by a factor of 10 to match the plot limit.

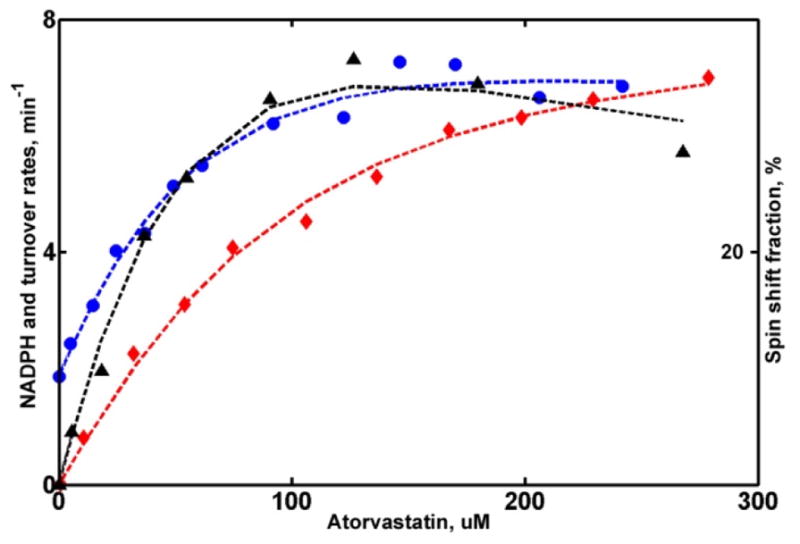

Metabolism of mixtures of DND with ARVS and ARVL

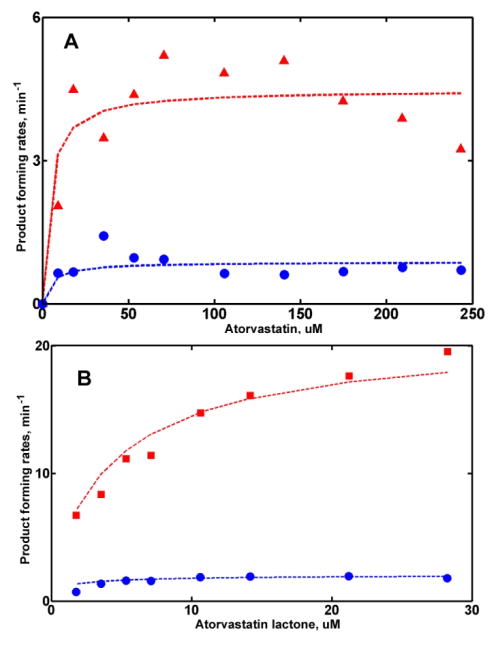

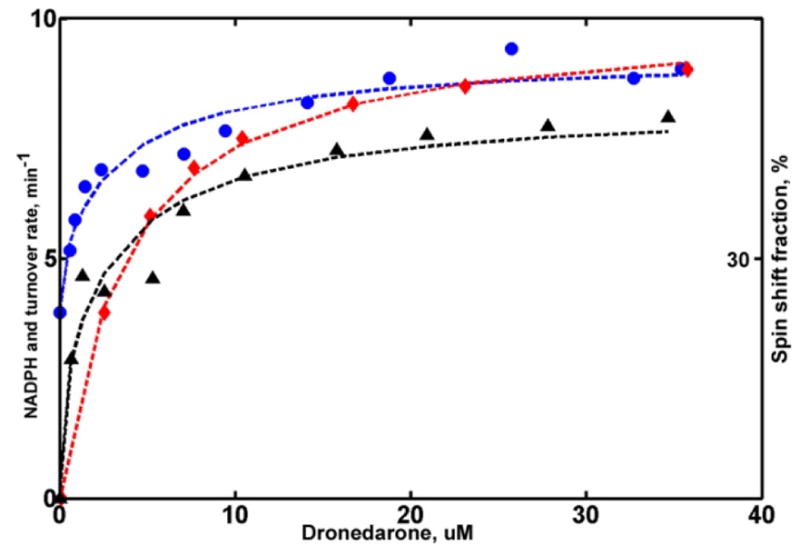

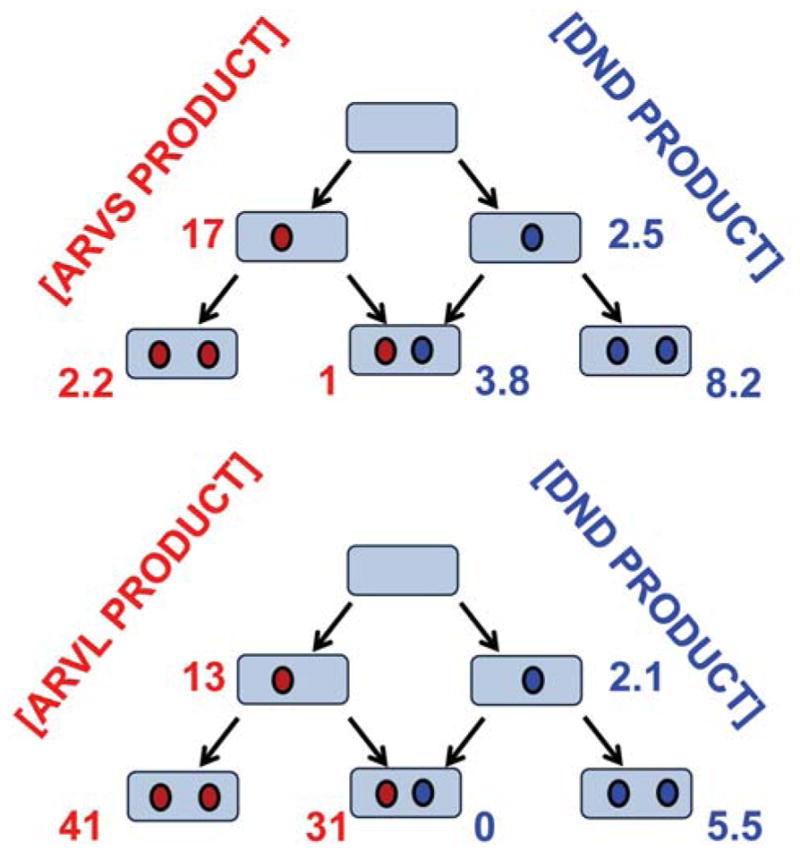

In order to understand the mutual effects of two drugs on their metabolism in the mixture, steady state turnover experiments were performed with the binary mixtures of substrates, i.e. ARVS, or ARVL, and DND. The results of these experiments can be analyzed using the parameters obtained from functional studies of CYP3A4 with pure substrates (Table 2). Parameters for the mixed intermediate with one of each substrate bound to the CYP3A4 monomer are obtained from the amounts of both products measured at various concentrations of substrates, but at the same stoichiometric ratios, as described in Methods. (Figure 6)

Figure 6.

Global analysis of turnover in the mixture of: (A) ARVS (triangles) and DND (circles); (B) ARVL (squares) and DND (circles).

For the mixture of ARVS and DND at a ratio of concentrations of 15:1, the turnover numbers resolved for the mixed intermediate show that the metabolic rates for both substrates are approximately two times lower than those measured for CYP3A4 with two molecules of the same substrate, 1 min−1 for ARVS (compare to 2.2 min−1 for pure ARVS, Table 2) and 3.8 min−1 for DND, vs. 8.2 min−1 for pure DND. This means that the interaction between ARVS and DND is not specific and can be considered as competitive binding at the active site resulting in competitive mutual inhibition. This type of drug-drug interactions was identified in a previous study of ARVS metabolism of CYP3A4 in the mixture with clopidogrel.(69)

Analysis of turnover experiments with the mixture of ARVL and DND performed at the constant molar ratio 2.9:1, shows that ARVL is predominantly metabolized when both substrates are bound to the CYP3A4 monomer in the Nanodisc. No product of DND metabolism was detected from the mixed intermediate, while the rate of ARVL metabolism, 31 min−1, was slightly lower than 41 min−1 measured for the CYP3A4 saturated with pure ARVL. (Figure 7)

Figure 7.

Summary of the results of the global analysis of CYP3A4 metabolism of mixtures of DND with ATVS and ATVL

Taken together, our results provide a detailed description of drug metabolism and drug-drug interactions for two widely used compounds, ARVS and DND, both of which are largely metabolized by CYP3A4. Using monomeric CYP3A4 incorporated in Nanodiscs, we resolved fractional contributions of binding intermediates with one or two substrates bound into the experimentally observed steady-state ARVS hydroxylation and DND demethylation catalyzed by CYP3A4. For pure DND metabolism the product turnover rate is three times faster when two substrates are bound, indicating moderate positive cooperativity. On the contrary, in the presence of ATVL, metabolism of DND is strongly inhibited. Comparison of ARVS and ARVL shows that binding is much more tight and hydroxylation is significantly faster for ARVL. This means that the main channel of atorvastatin metabolic removal from blood plasma is via ARVL, while only ARVS and hydroxylated metabolites are active with regards to the lipid lowering effect(70). As a consequence of these results, we focused MD simulation study only on the mechanism of drug-drug interactions between ARVL and DND.

Molecular Dynamics results

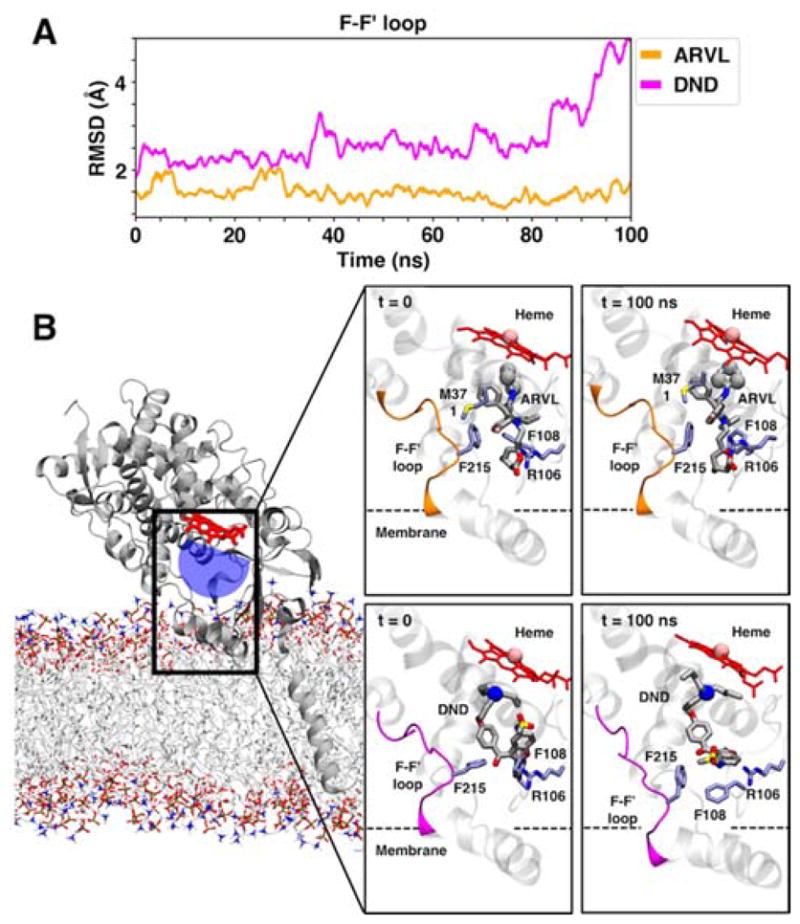

Productive binding of a single DND induces rearrangement of F-F″ loop

To investigate the molecular details of ARVL and DND binding to membrane-bound CYP3A4, we employed a combination of MD simulations with molecular docking of the two drugs in different configurations (see Methods section). The simulations performed are summarized in Table 1. Our first set of simulations started from molecular models where a single copy of the drug(DND or ARVL) was docked in either the productive, or allosteric site.

Analysis of the interaction energies of the drugs with residues in the productive site (labeled System 1 and System 2 in Table 1) reveals that ARVL and DND form mostly similar interactions with CYP3A4 (Table 2), occupying most of the volume in the active site cavity (Fig. 8). In our simulation of ARVL in the productive site, the lactone group of ARVL established electrostatic interactions with Arg-106 that stabilized its position near the heme. Interestingly, in our DND simulation, a rearrangement of the F-F′ region (formed by residues 212 to 219) was observed to stabilize a productive orientation of DND. After this rearrangement (with RMSD 5 Å relative to substrate free membrane-bound CYP3A4 model previously reported (53)), the side chains of Phe-108 and Phe-215 interact with the bicyclic portion of DND to stabilize a potentially productive orientation of this drug (Fig. 8). For ARVL no significant rearrangement of CYP3A4 is needed for accommodation of this substrate in a productive orientation

Figure 8.

Change in F-F′ loop in the presence of a drug in the productive site of CYP3A4. (Top) Time series of the backbone RMSD of the F-F′ loop of CYP3A4 (residues 209 to 218), calculated for System 1 and System 2 (Table 1). For the RMSD, the structure of our membrane-bound model of CYP3A4 reported in [1] was employed. (Bottom) Initial and final snapshots of ARVL and DND in the active site of CYP3A4 obtained from molecular docking and MD simulations. Protein in shown in cartoon representation, with the F-F′ loop highlighted in orange or magenta color for ARVL or DND simulations, respectively. The dashed line represents the average location of the membrane in the simulated systems. The drug, heme and important residues are shown in in stick representation. The iron of the heme and the sites of metabolism of each drug are shown as spheres.

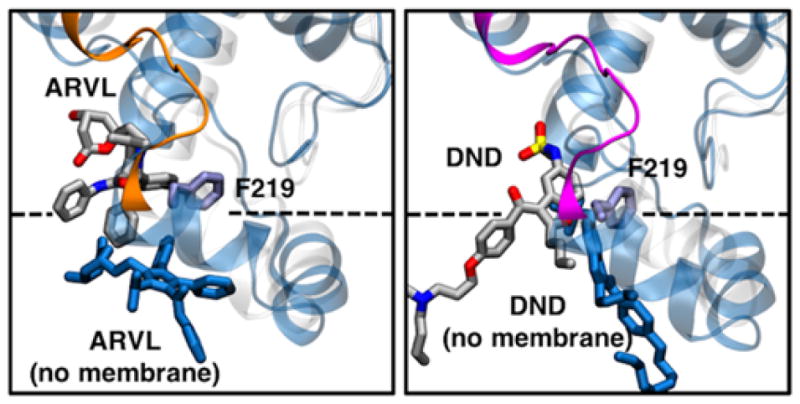

Our interaction energy analysis of the drugs in the allosteric site (System 3 and 4 in Table 1) showed that ARVL interacts with more protein residues than DND (Table S1). Interestingly, both drugs interact with Phe-219, located at the membrane interface, further suggesting that this is a key residue for allosteric modulation of metabolism of these drugs. Importantly, our control simulations of both substrates in the allosteric site in the absence of the membrane (System 5 and 6 in Table 1) showed that drug binding is not stable, and they are quickly repositioned away from the allosteric site (Figure 9). In the absence of the membrane, the drugs are significantly displaced from their initial position, despite their initial interactions with Phe-219 and other hydrophobic residues, highlighting the role of the lipid bilayer in stabilizing drug binding at the peripheral site of CYP3A4.

Figure 9.

Effect of the lipid bilayer on drug binding at the allosteric site of CYP3A4. Representative snapshots (i.e., most observed configuration during the simulations) of ARVL (left) and DND (right) bound in the allosteric site of CYP3A4. For the membrane simulations, protein, drug and Phe-219 side chain are shown using the same scheme as in Fig. 1. For the control simulations without the membrane, protein and drug are shown as blue cartoon and sticks, respectively.

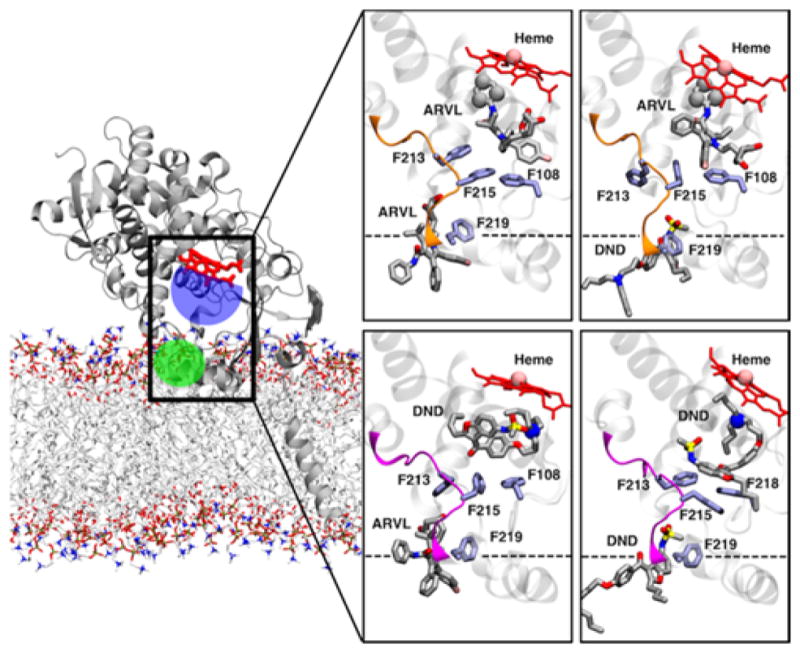

Binding of two drug molecules to membrane-bound CYP3A4

Starting from snapshots obtained from our simulations of drugs bound to the allosteric site of CPY3A4, we produced molecular models where two drugs were bound to CYP3A4 (see Methods). These models were then employed for additional MD simulations performed to elucidate the dynamics of membrane-bound CYP3A4 with two drugs bound to its binding sites. In these simulations, the drugs bound in the peripheral site retained their main interaction with residues located in the peripheral binding site (as shown in Table S1), with Phe-219 being the key residue for allosteric interactions.

The interactions energies of the drugs in the productive site of CYP3A4 calculated from our simulations consistently indicated a similar interaction pattern as in the single-drug case (Table S1), regardless of which drug was bound in the allosteric site. For ARVL, the main contributions come from hydrophobic residues, including Phe-108 and Met-371. Here, we point out that molecular docking of a second ARVL molecule in the productive site of CYP3A4 with ARVL in the allosteric site did not yield poses with the same orientation as in the single ARVL in the productive site simulation (System 1, Fig 8,) or when DND was in the allosteric site (System 8, shown in Fig. 10). This was due to subtle reorientation of side chains in the active site in our preliminary simulation of ARVL in the peripheral site with an empty productive site (System 3 in Table S1). However, the resulting docked pose that we simulated (System 7) still could potentially result in ARVL product formation, since the sites of metabolism remain close to the heme (e.g., within 5 Å of the heme iron). Overall, our simulations of ARVL in the active site did not show any significant changes when another drug was present in the allosteric site.

Figure 10.

Membrane-bound CYP3A4 with drugs in the productive and allosteric binding sites. Representative snapshots of CYP3A4 bound to two drug molecules. Dashed line represents the average location of the membrane in the simulations. Protein, drugs and key side chains are shown following the same scheme as described in Fig. 1. The iron of the heme and the sites of metabolism of drugs in the productive site are shown as spheres.

On the other hand, our simulations of DND in the active site in the presence of another drug bound to the allosteric site reveal notable differences. Interaction energies calculated from our simulations show a consistent interaction pattern with residues located in the active site cavity of CYP3A4 (Table S1). Notably, we observed that when ARVL was in the allosteric site (System 9 in Table 1, DND did not adopt a favorable orientation in the productive site during the 100 ns simulation (Figure 10). In contrast, when a second DND molecule was bound in the allosteric site, DND in the active site adopts a potentially productive orientation, consistent with our observation in System 2 simulation (Fig. 10). In this orientation, the bicyclic portion of DND interacts with hydrophobic side chains in the active site, including Phe-108, Phe-213 and Phe-215. Importantly, we did not observe any major F-F′ rearrangement in these DND simulations, which suggest that the presence of this drug in allosteric site changes orientation of side chains of several amino acids, which in turn modulates productive drug binding.

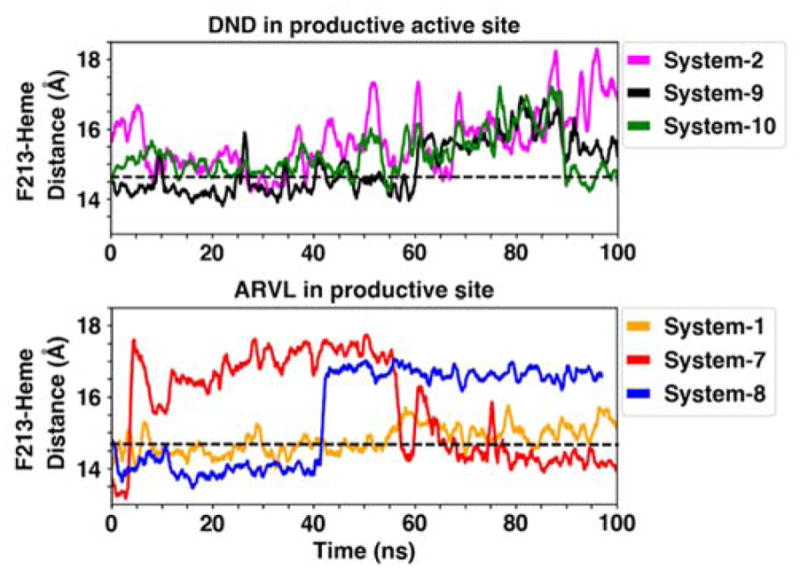

Interestingly, we observed that Phe-213, which we have previously identified as a key residue in progesterone and carbamazepine interactions with CYP3A4 (1), does not strongly interact with ARVL or DND at either binding site, appearing to contribute only transiently to binding (Table S1 and Table S2). This residue still underwent significant rearrangements during our simulations, transiently coming in and out of the active site as we have previously reported, especially when ARVL was located in the productive site (Figure 11). However these changes do not appear to be correlated to stable drug binding at either site.

Figure 11.

Dynamics of Phe-213 in drug-binding simulations. Time series of the center-of-mass distance of the Phe-213 side chain and the heme in out MD simulations. The dashed line indicates the average reference distance of 14.7 Å calculated from the apo membrane-bound CYP3A4 simulation, as we previously reported(1)

Discussion

Adverse drug interactions represent a common problem in modern clinical practice, especially when they involve drugs with low therapeutic window, including Multaq® (DND). Because interactions between DND and statins involve CYP3A4 (69, 70), but molecular mechanism is currently unknown, we decided to study this system. In order to evaluate the allosteric mechanism of drug-drug interactions mediated by CYP3A4 we combined global analysis of experimental functional studies with MD simulations. Combination of DND and ATVS provided better insight into the structural origin of observed effects than in previous work, because only one substrate molecule could bind to the active site, unlike two molecules of PGS or CBZ.(1) In addition, ARVL was also studied in combination with DND, because it exists in equilibrium with ARVS in humans in vivo (70) and is a good substrate for CYP3A4. Analysis of activity measurements and binding studies demonstrated that ARVL binds to CYP3A4 much tighter than ARVS and is the main player in drug-drug interactions with DND, appearing as a strong inhibitor of DND demethylation. ARVS also interacts with DND as a competitive inhibitor, although weak binding makes this interaction non-relevant at physiological concentrations.

Multiple MD simulations of CYP3A4 with substrate molecules bound in the active site, in allosteric site, and in both sites simultaneously, provided a consistent picture of molecular mechanism of allosteric effects in CYP3A4, and allowed to derive the main factors determining experimentally observed drug-drug interactions. These factors can be broadly categorized as structural and dynamic, and include size and shape of substrate molecules, their ability to perform the role of allosteric effector, and on positioning of CYP3A4 monomer in the membrane, where allosteric site is formed it the protein-lipid interface.

Substrate connection to the allosteric site

Size and structure of substrate molecule are decisive factors in the packing mode at the catalytic site and necessary conformational changes in CYP3A4 which help to position it against iron-oxygen intermediate critical for catalysis. When DND is bound at the active site, MD simulations show that productive orientation requires significant rearrangement of the F-F′ helix. This movement of residues 212 – 219 indicated direct communication between binding mode of this substrate and conformational changes at the allosteric site. As seen from activity data, this conformational change is compatible with binding of second DND molecule at the allosteric site, which improves rate of metabolism and coupling of DND demethylation. On the contrary, positioning of ARVL at the allosteric site changes conformation of F-F′ helix and forces DND to unproductive configuration. As a result, metabolism of DND in the mixed ARVL-DND intermediate is completely inhibited.

Binding of ARVL in a productive orientation at the active site does not require such a rearrangement of allosteric pocket, except for movements of Arg212, Phe213 and Phe215 side chains, which provide necessary space for the substrate near the heme. Neither F-F′ nor G-G′ loops undergo significant rearrangement, and thus do not suggest a high sensitivity of ARVL metabolism towards effector binding at the allosteric site. Comparison of residues interacting with ARVL at productive position in the absence of effectors with those in the presence of ARVL or DND at the allosteric site reveals replacement of Phe220, Ile223, and Val240 by Phe213 in both cases and also by Phe241 when two ARVL molecules are bound. Acceleration of ARVL metabolism in the presence of both ARVL and DND at the allosteric site may be attributed to better coupling, which is observed in both cases.

Role of the membrane

Control MD simulations without a membrane show initial unstable position of both substrates at the allosteric site, followed by quick dissociation. As it was observed previously for PGS(1), substrate binding as effector at the shallow crevice between F-F′ and G-G′ loops of CYP3A4 in solution is unstable. However, when enzyme is inserted into the membrane, lipid head groups render a pocket for the effector molecule, and thus the membrane is engaged in assisting and shaping of allosteric perturbation of substrate binding and metabolism.

Allosteric effect of binding at the effector site

ARVL at the allosteric site displaces DND from productive position, resulting in inhibition. Contrary, DND at the allosteric site stabilizes productive positioning of DND and improves turnover. This asymmetry demonstrates specific effects in the mixture, where DND and ARVL competitively bind to the allosteric site with opposite effect on DND metabolism. This is a new aspect of competitive binding, unlike simple competitive binding at the catalytic site, which results in inhibition, competitive binding to the allosteric site may result in activation, homotropic (as with DND in both sites), or heterotropic (as PGS activating CBZ metabolism,(1)).

Specific interactions of effectors and substrates with CYP3A4

With both DND and ARVL it is Phe219 interacting with both substrate and effector as the most important residue in mediating the observed allosteric effects, while with PGS and CBZ the main switch was Phe213. This difference underscores importance of specific details of molecular structures of substrate and effector interacting with CYP3A4.

In conclusion, we performed experimental characterization of the mechanism of heterotropic interactions between two popular drugs, atorvastatin and dronedarone, and found structural origin of these drug-drug interactions using a series of MD simulations. In the absence of DND, ARVS is metabolized faster when only one substrate is bound. A second binding induces significant inhibition observed at high concentrations. ARVL binds much tighter than ARVS, and is metabolized faster, manifesting apparent positive functional cooperativity. This makes ARVL the major player in drug-drug interactions with DND.

In the absence of ARVL or ARVS, DND is metabolized faster when two substrate molecules are bound. The second binding happens with much lower affinity, significantly increases spin shift and coupling, and reveals positive cooperativity and acceleration of metabolism in the presence of DND at the allosteric site.

In the presence of DND, metabolism of ARVS is strongly inhibited, as well as DND metabolism is also inhibited at high (non-physiological) concentrations of ARVS. In this pair mutual effects are due to competitive binding, as both substrates are metabolized with comparable rates from [11] intermediate. Rates of their metabolism are approximately two-fold lower than from doubly ligated binding intermediates [20] and [02], suggesting weak or no allosteric interactions between ARVS and DND.

ARVL is a better substrate than ARVS and is metabolized preferentially in the mixture with DND. In addition, ARVL interaction with DND results in asymmetric drug-drug interactions in CYP3A4 metabolism. With DND is present in the active site, binding of ARVL at the allosteric site displaces DND molecule from productive orientation to non-productive position and results in complete inhibition of DND metabolism. In contrast, DND binding at the allosteric site does not change productive orientation of ARVL in the catalytic site and no inhibition of ARVL metabolism is observed.

MD simulations results are in a good agreement with experiment and reveal important structural rearrangements giving insight into allosteric regulation in CYP3A4. When a DND molecule is bound at the allosteric site, productive positioning of the second DND molecule at the catalytic site is stabilized. On the contrary, binding of ARVL and ARVS at the allosteric site perturbs orientation of DND at the active site and displaces it from productive position. Importantly, control simulations with the same substrates placed at the allosteric site of CYP3A4 with no membrane present did not result in stable complexes, indicating that membrane incorporation of CYP3A4 is critically important for the correct functioning of allosteric regulation.

Taken together, our results enable assessing the details of molecular mechanism of allosteric modulation of CYP3A4 metabolism. This mechanism of drug-drug interactions mediated by CYP3A4 involves an allosteric site at the protein-membrane interface, formed by F-F′ and G-G′ loops and lipid head-groups. Binding of effectors at this site changes conformation and dynamics of the CYP3A4 catalytic site and, as a result, may inhibit or activate drug metabolism and clearance. Analysis and prediction of possible drug-drug interactions can be done experimentally, by running functional studies using a mixed titration approach, and by MD simulations, in order to quickly probe the effects of variations in the chemical structure of target compounds. The presence of a lipid membrane is critically important, because the binding mode of any effector molecule at the allosteric site is determined by the lipid – protein interactions.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

Global analysis of CYP3A4 metabolism of ATVS. NADPH oxidation rates (circles), product formation rates (triangles) and percent of high spin (diamonds) are fitted as a function of substrate concentrations as described in Methods section. Rate of NADPH consumption is scaled by a factor of 20 to match the plot limit.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a MIRA grant from the National Institutes of Health R35 GM118145.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Denisov IG, Grinkova YV, Baylon JL, Tajkhorshid E, Sligar SG. Mechanism of Drug-Drug Interactions Mediated by Human Cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 Monomer. Biochemistry. 2015;54:2227–2239. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mast N, Li Y, Linger M, Clark M, Wiseman J, Pikuleva IA. Pharmacologic Stimulation of Cytochrome P450 46A1 and Cerebral Cholesterol Turnover in Mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289:3529–3538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.532846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mast N, Linger M, Pikuleva IA. Inhibition and stimulation of activity of purified recombinant CYP11A1 by therapeutic agents. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;371:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egnell A-C, Houston JB, Boyer CS. Predictive models of CYP3A4 heteroactivation: in vitro-in vivo scaling and pharmacophore modeling. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2005;312:926–937. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosa A, Neunzig J, Gerber A, Zapp J, Hannemann F, Pilak P, Bernhardt R. 2beta- and 16beta-hydroxylase activity of CYP11A1 and direct stimulatory effect of estrogens on pregnenolone formation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blobaum AL, Byers FW, Bridges TM, Locuson CW, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Daniels JS. A Screen of Approved Drugs Identifies the Androgen Receptor Antagonist, Flutamide, and its Pharmacologically Active Metabolite, 2-Hydroxy-Flutamide, as Heterotropic Activators of CYP 3A In vitro and In vivo. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015 doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.064006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed JR, Backes WL. The functional effects of physical interactions involving cytochromes P450: putative mechanisms of action and the extent of these effects in biological membranes. Drug Metabolism Reviews. 2016;48:453–469. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2016.1221961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed JR, Backes WL. Formation of P450. P450 complexes and their effect on P450 function. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott EE, Wolf CR, Otyepka M, Humphreys SC, Reed JR, Henderson CJ, McLaughlin LA, Paloncyova M, Navratilova V, Berka K, Anzenbacher P, Dahal UP, Barnaba C, Brozik JA, Jones JP, Estrada DF, Laurence JS, Park JW, Backes WL. The Role of Protein-Protein and Protein-Membrane Interactions on P450 Function. Drug Metab Dispos. 2016;44:576–590. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.068569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davydov DR, Halpert JR. Allosteric P450 mechanisms: multiple binding sites, multiple conformers or both? Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4:1523–1535. doi: 10.1517/17425250802500028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davydov DR, Davydova NY, Sineva EV, Kufareva I, Halpert JR. Pivotal role of P450-P450 interactions in CYP3A4 allostery: the case of alpha-naphthoflavone. Biochem J. 2013;453:219–230. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davydov DR, Davydova NY, Sineva EV, Halpert JR. Interactions among Cytochromes P450 in Microsomal Membranes: Oligomerization of Cytochromes P450 3A4, 3A5 and 2E1 and its Functional Consequences. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:3850–3864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.615443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davydov DR. Microsomal monooxygenase as a multienzyme system: the role of P450-P450 interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7:543–558. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.562194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sligar SG, Denisov IG. Understanding Cooperativity in Human P450 Mediated Drug-Drug Interactions. Drug Metab Rev. 2007;39:567–579. doi: 10.1080/03602530701498521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denisov IG, Frank DJ, Sligar SG. Cooperative properties of cytochromes P450. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;124:151–167. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denisov IG, Sligar SG. A novel type of allosteric regulation: functional cooperativity in monomeric proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;519:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domanski TL, He YA, Khan KK, Roussel F, Wang Q, Halpert JR. Phenylalanine and tryptophan scanning mutagenesis of CYP3A4 substrate recognition site residues and effect on substrate oxidation and cooperativity. Biochemistry-Us. 2001;40:10150–10160. doi: 10.1021/bi010758a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xue L, Wang HF, Wang Q, Szklarz GD, Domanski TL, Halpert JR, Correia MA. Influence of P450 3A4 SRS-2 residues on cooperativity and/or regioselectivity of aflatoxin B(1) oxidation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:483–491. doi: 10.1021/tx000218z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan KK, He YQ, Domanski TL, Halpert JR. Midazolam oxidation by cytochrome P450 3A4 and active-site mutants: an evaluation of multiple binding sites and of the metabolic pathway that leads to enzyme inactivation. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:495–506. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korzekwa KR, Krishnamachary N, Shou M, Ogai A, Parise RA, Rettie AE, Gonzalez FJ, Tracy TS. Evaluation of Atypical Cytochrome P450 Kinetics with Two-Substrate Models: Evidence That Multiple Substrates Can Simultaneously Bind to Cytochrome P450 Active Sites. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4137–4147. doi: 10.1021/bi9715627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shou M, Dai R, Cui D, Korzekwa KR, Baillie TA, Rushmore TH. A kinetic model for the metabolic interaction of two substrates at the active site of cytochrome P450 3A4. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2256–2262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosea NA, Miller GP, Guengerich FP. Elucidation of distinct ligand binding sites for cytochrome P450 3A4. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5929–5939. doi: 10.1021/bi992765t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galetin A, Clarke SE, Houston JB. Quinidine and haloperidol as modifiers of CYP3A4 activity: multisite kinetic model approach. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2002;30:1512–1522. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.12.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernando H, Halpert JR, Davydov DR. Resolution of multiple substrate binding sites in cytochrome P450 3A4: the stoichiometry of the enzyme-substrate complexes probed by FRET and Job’s titration. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4199–4209. doi: 10.1021/bi052491b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsalkova TN, Davydova NY, Halpert JR, Davydov DR. Mechanism of interactions of alpha-naphthoflavone with cytochrome P450 3A4 explored with an engineered enzyme bearing a fluorescent probe. Biochemistry. 2007;46:106–119. doi: 10.1021/bi061944p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller CS, Knehans T, Davydov DR, Bounds PL, von Mandach U, Halpert JR, Caflish A, Koppenol WH. Concurrent Cooperativity and Substrate Inhibition in the Epoxidation of Carbamazepine by Cytochrome P450 3A4 Active Site Mutants Inspired by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biochemistry. 2015;54:711–721. doi: 10.1021/bi5011656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cameron MD, Wen B, Roberts AG, Atkins WM, Campbell AP, Nelson SD. Cooperative binding of aceta-minophen and caffeine within the P450 3A4 active site. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:1434–1441. doi: 10.1021/tx7000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nath A, Fernandez C, Lampe JN, Atkins WM. Spectral resolution of a second binding site for Nile Red on cyto-chrome P4503A4. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;474:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nath A, Koo PK, Rhoades E, Atkins WM. Allosteric effects on substrate dissociation from cytochrome P450 3A4 in nanodiscs observed by ensemble and single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15746–15747. doi: 10.1021/ja805772r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams PA, Cosme J, Vinkovic DM, Ward A, Angove HC, Day PJ, Vonrhein C, Tickle IJ, Jhoti H. Crystal structures of human cytochrome P450 3A4 bound to metyrapone and progesterone. Science. 2004;305:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1099736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denisov IG, Shih AY, Sligar SG. Structural differences between soluble and membrane bound cytochrome P450s. J Inorg Biochem. 2012;108:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denisov IG, Grinkova YV, Baas BJ, Sligar SG. The ferrous-dioxygen intermediate in human cytochrome P450 3A4: Substrate dependence of formation of decay kinetics. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:23313–23318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denisov IG, Grinkova YV, McLean MA, Sligar SG. The one-electron autoxidation of human cytochrome P450 3A4. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:26865–26873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denisov IG, Baas BJ, Grinkova YV, Sligar SG. Cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4: Linkages in substrate binding, spin state, uncoupling, and product formation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:7066–7076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank DJ, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Analysis of heterotropic cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4 using alpha-naphthoflavone and testosterone. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5540–5545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.182055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao S, Juhaeri J, Schiappacasse HA, Koren AT, Dai WS. Evaluation of dronedarone use in the US patient population between 2009 and 2010: a descriptive study using a claims database. Clin Ther. 2011;33:1483–1490e1483. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaik AN, Bohnert T, Williams DA, Gan LL, LeDuc BW. Mechanism of Drug-Drug Interactions Between Warfarin and Statins. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105:1976–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schafer JA, Kjesbo NK, Gleason PP. Dronedarone: current evidence and future questions. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;28:38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2009.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang YC, Hsieh TC, Chou CL, Wu JL, Fang TC. Risks of Adverse Events Following Coprescription of Statins and Calcium Channel Blockers: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2487. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel G, King A, Dutta S, Korb S, Wade JR, Foulds P, Sumeray M. Evaluation of the effects of the weak CYP3A inhibitors atorvastatin and ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate on lomitapide pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56:47–55. doi: 10.1002/jcph.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanger U, Klein K, Thomas M, Rieger J, Tremmel R, Kandel B, Klein M, Magdy T. Genetics, Epigenetics, and Regulation of Drug-Metabolizing Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Clin Pharmacol Ther (N Y, NY, U S) 2014 doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.220. Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis MW, Wason S. Effect of steady-state atorvastatin on the pharmacokinetics of a single dose of colchicine in healthy adults under fasted conditions. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34:259–267. doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong Y, Chia YM, Yeo RH, Venkatesan G, Koh SK, Chai CL, Zhou L, Kojodjojo P, Chan EC. Inactivation of Human Cytochrome P450 3A4 and 3A5 by Dronedarone and N-Desbutyl Dronedarone. Mol Pharmacol. 2016;89:1–13. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.100891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klieber S, Arabeyre-Fabre C, Moliner P, Marti E, Mandray M, Ngo R, Ollier C, Brun P, Fabre G. Identification of metabolic pathways and enzyme systems involved in the in vitro human hepatic metabolism of dronedarone, a potent new oral antiarrhythmic drug. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2014;2:e00044. doi: 10.1002/prp2.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamargo J, Lopez-Farre A, Caballero R, Delpon E. Dronedarone. Drugs Today (Barc) 2011;47:109–133. doi: 10.1358/dot.2011.47.2.1545699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang T. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of disposition and drug-drug interactions for atorvastatin and its metabolites. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2015;77:216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Denisov IG, Grinkova YV, Lazarides AA, Sligar SG. Directed self-assembly of monodisperse phospholipid bi-layer Nanodiscs with controlled size. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3477–3487. doi: 10.1021/ja0393574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grinkova YV, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Functional reconstitution of monomeric CYP3A4 with multiple cytochrome P450 reductase molecules in Nanodiscs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Domanski TL, He YA, Harlow GR, Halpert JR. Dual role of human cytochrome P450 3A4 residue Phe-304 in substrate specificity and cooperativity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:585–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Cera E. Thermodynamic Theory of Site-Specific Binding Processes in Biological Macromolecules. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frank DJ, Denisov IG, Sligar SG. Mixing apples and oranges: Analysis of heterotropic cooperativity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2009;488:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yano JK, Wester MR, Schoch GA, Griffin KJ, Stout CD, Johnson EF. The structure of human microsomal cytochrome P450 3A4 determined by X-ray crystallography to 2.05-A resolution. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:38091–38094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baylon JL, Lenov IL, Sligar SG, Tajkhorshid E. Characterizing the membrane-bound state of cytochrome P450 3A4: structure, depth of insertion, and orientation. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:8542–8551. doi: 10.1021/ja4003525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VDM: visual molecular dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. plates, 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacKerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FT, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacKerell AD, Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL., III Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: Limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004;25:1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hart K, Foloppe N, Baker CM, Denning EJ, Nilsson L, MacKerell AD. Optimization of the CHARMM Additive Force Field for DNA: Improved Treatment of the BI/BII Conformational Equilibrium. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2012;8:348–362. doi: 10.1021/ct200723y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klauda JB, Venable RM, Freites JA, O’Connor JW, Tobias DJ, Mondragon-Ramirez C, Vorobyov I, MacKerell AD, Pastor RW. Update of the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2010;114:7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, Darian E, Guvench O, Lopes P, Vorobyov I, Mackerell AD., Jr CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2010;31:671–690. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mayne CG, Saam J, Schulten K, Tajkhorshid E, Gumbart JC. Rapid parameterization of small molecules using the force field toolkit. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2013;34:2757–2770. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feller SE, Zhang Y, Pastor RW, Brooks BR. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: the Langevin piston method. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1995;103:4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martyna GJ, Tobias DJ, Klein ML. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1994;101:4177–4189. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller GP, Guengerich FP. Binding and oxidation of alkyl 4-nitrophenyl ethers by rabbit cytochrome P450 1A2: Evidence for two binding sites. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7262–7272. doi: 10.1021/bi010402z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Collom SL, Laddusaw RM, Burch AM, Kuzmic P, Perry MD, Jr, Miller GP. CYP2E1 substrate inhibition. Mechanistic interpretation through an effector site for monocyclic compounds. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:3487–3496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707630200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Clarke TA, Waskell LA. The metabolism of clopidogrel is catalyzed by human cytochrome P450 3A and is inhibited by atorvastatin. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:53–59. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riedmaier S, Klein K, Winter S, Hofmann U, Schwab M, Zanger UM. Paraoxonase (PON1 and PON3) Polymorphisms: Impact on Liver Expression and Atorvastatin-Lactone Hydrolysis. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:41. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2011.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.