Abstract

Background

Treatment guidelines for colon cancer recommend colectomy with lymphadenectomy of at least 12 lymph nodes for stage I to III disease as surgery adherence (SA), and adjuvant chemotherapy (C) for stage III. We evaluated adherence to these guidelines among older Texas colon cancer patients and the associated survival outcomes.

Methods

Using Texas Cancer Registry (TCR) linked with Medicare data, we included stage II and III colon cancer patients ≥66 years diagnosed between 2001 and 2011. SA and C adherence rates to treatment guidelines were estimated. Chi-square test, general linear regression, survival probability and Cox regression were used to identify factors associated with adherence and survival.

Results

SA increased from 47.2% to 84% among 6029 stage II or III patients from year 2001 to 2011, and C increased from 48.9% to 53.1% for stage III patients. SA was associated with marital status, tumor size, surgeon’s specialty and diagnosis year. Patients’ age, sex, marital status, Medicare state-buy-in status, comorbidity status, and diagnosis year were associated with C. The five-year survival probability for patients with guideline-concordant treatment was the highest; 87% for stage II and 73% for stage III. After adjusting for demographic and tumor characteristics, improved cancer-cause specific survival was associated with the receipt of stage-specific guideline-concordant treatment for stage II or III patients.

Conclusions

The adherence to guideline-concordant treatment among Texas older colon cancer patients improved over time, and it was associated with better survival outcomes. Future studies should be focused on identifying interventions to improve guideline-concordant treatment adherence.

Keywords: colon cancer, stage II and III, treatment adherence, lymphadenectomy of at least 12 lymph nodes, cancer-specific survival

Introduction

Stage II or III colon cancer patients had better five-year survival if they received guideline-concordant treatment[1]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) surgery guidelines for stages I–III colon cancer include colectomy with lymphadenectomy of at least 12 nearby lymph nodes; we denote this as surgery adherence (SA) [2]. For stage III colon cancer, the NCCN recommends using 5-FU/leucovorin or capecitabine. The adding oxaliplatin to 5-FU/leucovorin in patients ≥ 70 years is uncertain as it has not shown a survival benefit [2]. Since patients treated according to guideline recommendations have better survival outcomes [1, 3–5], it is important to estimate the rate of guideline-concordant colon cancer care to monitor the quality of cancer treatment.

Each year, about 9,000 Texans are diagnosed with colorectal cancer and about 60% of them are ≥65 years [6]. The five-year survival rate for regional stage (which included stage II and III ) patients were 68.2% and the cost of colorectal cancer care was about $3.6 billion in Texas in 2007[6]. In order to reduce the colon cancer burden and provide effective cancer care to Texas patients, we evaluated the trends in adherence to evidence-based guidelines for stage II and III colon cancer patients diagnosed between 2001 and 2011. We hypothesized that the adherence increased over the years analyzed, and it was associated with the increased survival of colon cancer patients.

Materials and methods

We used TCR data linked with Medicare for this study. The Texas cancer patients were linked with the Medicare data by matching patients’ social security number, name, sex, and date of birth[7]. We identified colon cancer patients who were diagnosed between 2001 and 2011 by using The International Classification of Disease for Oncology (ICD-O-3)/WHO 2008 Site Recode B recodes 21041–21049. Since the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging was not recorded in the TCR before 2006, we selected patients with regional stage disease with tumor direct extension without regional lymph nodes invasion (stage II), and regional nodal involvement (stage III). Patients were ≥ 66 years, with Medicare Part A and B and not covered by a health maintenance organization for 1 year prior to and 1 year after diagnosis or until death if patients died within 12 months after diagnosis. The index month for the cohort selection was patients’ cancer diagnosis month. Patients had colectomy within 6 months since index month and survived at least six months after cancer diagnosis. Details about the cohort selection are in Supplemental Table 1.

We included patient-level covariates such as demographics, socioeconomic status, residence area, tumor characteristics, surgery and chemotherapy, surgeon’s specialty and comorbidity status at diagnosis. Charlson comorbidity status was generated using Medicare claims [8, 9]. We defined surgery as conventional colectomy or laparoscopy-assisted colectomy by using ICD-9-CM procedure or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT)/Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes. Receipt of chemotherapy was defined by whether the patient had their first claim for fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, capecitabine or leucovorin after colectomy and within four months after colon cancer diagnosis. We defined surgeon’s specialty by using the Medicare Specialty Codes in the surgery claims from physician files. The codes for defining surgery and chemotherapy are in Supplemental Table 2.

SA was defined as a patient receiving colectomy with lymphadenectomy of at least 12 lymph nodes. Adjuvant chemotherapy (C) adherence for stage III patients was defined as initiating chemotherapy within 4 months of diagnosis after colectomy in patients 80 years or younger according to the treatment guidelines published by NCCN, National Quality Forum and the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) [10].

We evaluated the survival outcomes for patients based on stage-specific treatment. Patients were divided into four treatment groups according to patients’ SA and C: colectomy with < 12 lymph nodes removed with no chemotherapy (S), SA with no chemotherapy (SA), S followed by chemotherapy (S+C), SA followed by chemotherapy (SA+C). We defined stage-specific adherence to treatment guidelines as SA for stage II and SA+C for stage III. We estimated the five-year colon cancer-specific survival (CSS). The survival time was calculated from the diagnosis month till death month or end of the study. If a patient was alive or died due to causes other than colon cancer, the patient was censored at one of the following time points (whichever had occurred first): 1) date of death; 2) five years if the patient survived more than five years; 3) December 31, 2012 (the end date of our available Medicare claims) if the patient was followed up for less than five years.

Means, medians and frequencies were used to describe continuous and categorical variables. We used chi-square test to compare the characteristics distribution of the adherent and non-adherent patients for nominal variables and Cochrane-Armitage trend test for ordinal categorical variables. Since the adherence rate was found to be greater than 10%, we used general linear regression analysis to compute risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to evaluate the association of these factors with adherence status [11].

We estimated the stage-specific adherence rate and computed the five-year CSS using the Kaplan-Meier method and conducted pairwise log-rank test to compare survival rates by treatment groups. In Cox regression analysis of evaluating association between treatment adherence and patients’ survival, we used propensity score (PS) adjustment to control the differences in patients’ baseline prognosis factors of receiving a specific cancer treatment. We first computed the PS for each patient who received a specific treatment by using multinomial logistic regression model, and then we calculated the inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) using the PS. Finally, we used forward stepwise Cox regression model adjusted for other covariates and IPTW to obtain the hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% CI for CSS for the each of the three non-adherence groups. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of p ≤ 0.1 was used to select variables in the final Cox model.

All statistical tests were two-sided at a significance level of 0.05 by using SAS 9.4 software developed by SAS Institute (Cary, North Carolina). This research received exemption from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 2161 stage II and 3868 stage III Texas colon cancer patients who received colectomy within 6 months of diagnosis; patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. About 64.4% of these 6029 stage II or III patients received SA. The age distribution for SA and non-SA were similar, with a median age of 76 years for both groups. The median number of lymph nodes examined was 18 for SA and 8 for non-SA. From 2001 to 2011, the SA rate steadily increased from 47.2% to 84.0%. Patients who were married, with stage III disease, large tumor size or operated on by a colorectal specialist surgeon were more likely to have SA. The C rate was 50.3% among the 2737 stage III patients who were ≤ 80 years. Over the 11 year period, the C rate increased from 48.9% in 2001 to 56.2% in 2005, and then slightly decreased to 53.1% in 2011. There was no significant increasing trend for C during the years examined. Factors associated with non-adherence to chemotherapy guidelines included being older than 75 years, male, and having a Charlson comorbidity score > 1. Patients’ marital status and year of diagnosis were significantly associated with SA and C. Patients who had Medicare covered by a state buy-in program were 18% less likely to have C compared with those not enrolled in a state buy-in program (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of stage II or III colon cancer patients by adherence to treatment guidelines

| Variables | Surgery Adherence Stage II or III |

Chemotherapy Adherence Stage III (age 80 years or younger) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (Column%) | Yes (Row%) | P | N (Column%) | Yes (Row%) | P | |

| Total | 6029 (100) | 3880 ( 64.4 ) | 2737 ( 100 ) | 1378 ( 50.3 ) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 66–70 | 1290 ( 21.4 ) | 841 ( 65.2 ) | 0.43 | 875 ( 32.0 ) | 478 ( 54.6 ) | <.01 |

| 71–75 | 1501 ( 24.9 ) | 957 ( 63.8 ) | 990 ( 36.2 ) | 516 ( 52.1 ) | ||

| 76–80 | 1351 ( 22.4 ) | 888 ( 65.7 ) | 872 ( 31.9 ) | 384 ( 44.0 ) | ||

| >80 | 1887 ( 31.3 ) | 1194 ( 63.3 ) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 3433 ( 56.9 ) | 2253 ( 65.6 ) | 0.02 | 1448 ( 52.9 ) | 754 ( 52.1 ) | 0.06 |

| Male | 2596 ( 43.1 ) | 1627 ( 62.7 ) | 1289 ( 47.1 ) | 624 ( 48.4 ) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 4524 ( 75.0 ) | 2979 ( 65.8 ) | <.01 | 1964 ( 71.8 ) | 1020 ( 51.9 ) | 0.05 |

| Hispanic | 853 ( 14.1 ) | 498 ( 58.4 ) | 442 ( 16.1 ) | 209 ( 47.3 ) | ||

| Black | 553 ( 9.2 ) | 328 ( 59.3 ) | 281 ( 10.3 ) | 124 ( 44.1 ) | ||

| Other | 99 ( 1.6 ) | 75 ( 75.8 ) | 50 ( 1.8 ) | 25 ( 50.0 ) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 2220 ( 36.8 ) | 1465 ( 66.0 ) | <.01 | 1160 ( 42.4 ) | 628 ( 54.1 ) | <.01 |

| Not married | 1761 ( 29.2 ) | 1175 ( 66.7 ) | 668 ( 24.4 ) | 303 ( 45.4 ) | ||

| Unknown | 2048 ( 34.0 ) | 1240 ( 60.5 ) | 909 ( 33.2 ) | 447 ( 49.2 ) | ||

| State buy-in status | ||||||

| No | 5065 ( 84.0 ) | 3303 ( 65.2 ) | <.01 | 2303 ( 84.1 ) | 1204 ( 52.3 ) | <.01 |

| Yes | 964 ( 16.0 ) | 577 ( 59.9 ) | 434 ( 15.9 ) | 174 ( 40.1 ) | ||

| Cancer stage | ||||||

| Stage II | 2161 ( 35.8 ) | 1277 ( 59.1 ) | <.01 | |||

| Stage III | 3868 ( 64.2 ) | 2603 ( 67.3 ) | ||||

| Tumor grade* | ||||||

| I | 345 ( 5.7 ) | 206 ( 59.7 ) | <.01 | 150 ( 5.5 ) | 72 ( 48.0 ) | 0.29 |

| II | 4017 ( 66.6 ) | 2574 ( 64.1 ) | 1747 ( 63.8 ) | 873 ( 50.0 ) | ||

| III | 1389 ( 23.0 ) | 923 ( 66.5 ) | 702 ( 25.6 ) | 367 ( 52.3 ) | ||

| IV | 55 ( 0.9 ) | 42 ( 76.4 ) | 29 ( 1.1 ) | 14 ( 48.3 ) | ||

| Unknown | 223 ( 3.7 ) | 135 ( 60.5 ) | 109 ( 4.0 ) | 52 ( 47.7 ) | ||

| Tumor size(mm) | ||||||

| 0–31 | 1402 ( 23.3 ) | 821 ( 58.6 ) | <.01 | 740 ( 27.0 ) | 378 ( 51.1 ) | 0.95 |

| 32–44 | 1604 ( 26.6 ) | 1051 ( 65.5 ) | 731 ( 26.7 ) | 373 ( 51.0 ) | ||

| 45–59 | 1242 ( 20.6 ) | 835 ( 67.2 ) | 515 ( 18.8 ) | 264 ( 51.3 ) | ||

| ≥60 | 1249 ( 20.7 ) | 904 ( 72.4 ) | 500 ( 18.3 ) | 254 ( 50.8 ) | ||

| Unknown | 532 ( 8.8 ) | 269 ( 50.6 ) | 251 ( 9.2 ) | 109 ( 43.4 ) | ||

| Surgery type | ||||||

| Conventional | 5002 ( 83.0 ) | 3064 ( 61.3 ) | <.01 | 2226 ( 81.3 ) | 1115 ( 50.1 ) | 0.57 |

| Laparoscopic | 1027 ( 17.0 ) | 816 ( 79.5 ) | 511 ( 18.7 ) | 263 ( 51.5 ) | ||

| Surgeon Type | ||||||

| General surgeon | 4121 ( 68.4 ) | 2537 ( 61.6 ) | <.01 | 1823 ( 66.6 ) | 931 ( 51.1 ) | 0.28 |

| Specialty& | 1141 ( 18.9 ) | 867 ( 76.0 ) | 563 ( 20.6 ) | 287 ( 51.0 ) | ||

| Other | 236 ( 3.9 ) | 150 ( 63.6 ) | 120 ( 4.4 ) | 53 ( 44.2 ) | ||

| Unknown | 531 ( 8.8 ) | 326 ( 61.4 ) | 231 ( 8.4 ) | 107 ( 46.3 ) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity | ||||||

| 0 | 3809 ( 63.2 ) | 2441 ( 64.1 ) | 0.83 | 1742 ( 63.6 ) | 921 ( 52.9 ) | <.01 |

| 1 | 1397 ( 23.2 ) | 914 ( 65.4 ) | 652 ( 23.8 ) | 316 ( 48.5 ) | ||

| >1 | 823 ( 13.7 ) | 525 ( 63.8 ) | 343 ( 12.5 ) | 141 ( 41.1 ) | ||

| Year at diagnosis | ||||||

| 2001 | 665 ( 11.0 ) | 314 ( 47.2 ) | <.01 | 266 ( 9.7 ) | 130 ( 48.9 ) | 0.17 |

| 2002 | 716 ( 11.9 ) | 363 ( 50.7 ) | 287 ( 10.5 ) | 139 ( 48.4 ) | ||

| 2003 | 680 ( 11.3 ) | 314 ( 46.2 ) | 304 ( 11.1 ) | 149 ( 49.0 ) | ||

| 2004 | 632 ( 10.5 ) | 365 ( 57.8 ) | 313 ( 11.4 ) | 144 ( 46.0 ) | ||

| 2005 | 620 ( 10.3 ) | 373 ( 60.2 ) | 283 ( 10.3 ) | 159 ( 56.2 ) | ||

| 2006 | 581 ( 9.6 ) | 410 ( 70.6 ) | 283 ( 10.3 ) | 149 ( 52.7 ) | ||

| 2007 | 521 ( 8.6 ) | 413 ( 79.3 ) | 247 ( 9.0 ) | 120 ( 48.6 ) | ||

| 2008 | 419 ( 6.9 ) | 330 ( 78.8 ) | 210 ( 7.7 ) | 96 ( 45.7 ) | ||

| 2009 | 411 ( 6.8 ) | 340 ( 82.7 ) | 190 ( 6.9 ) | 105 ( 55.3 ) | ||

| 2010 | 416 ( 6.9 ) | 349 ( 83.9 ) | 177 ( 6.5 ) | 93 ( 52.5 ) | ||

| 2011 | 368 ( 6.1 ) | 309 ( 84.0 ) | 177 ( 6.5 ) | 94 ( 53.1 ) | ||

Tumor grade I to IV is well, moderately, poorly, and undifferentiated, respectively.

Specialty: colorectal surgeon or surgical oncology

Table 2.

Factors associated with surgery or chemotherapy adherence among stage II or III colon cancer patients

| Variable | Stratum | Stage II or III N=6029 Risk ratio (95%CI) |

P | Stage III N=2737 Risk ratio (95%CI) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years | 66–70 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 71–75 | 1.00 ( 0.97, 1.02 ) | 0.76 | 0.96 ( 0.88, 1.05 ) | 0.36 | |

| 76–80 | 1.00 ( 0.97, 1.03 ) | 0.89 | 0.83 ( 0.76, 0.92 ) | <.01 | |

| >80 | 0.99 ( 0.96, 1.01 ) | 0.35 | NA | ||

| Sex | Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 0.99 ( 0.97, 1.00 ) | 0.14 | 0.88 ( 0.81, 0.95 ) | <.01 | |

| Race | White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 0.99 ( 0.96, 1.03 ) | 0.68 | 0.96 ( 0.84, 1.08 ) | 0.48 | |

| Black | 0.97 ( 0.93, 1.00 ) | 0.07 | 0.91 ( 0.79, 1.05 ) | 0.18 | |

| Other | 1.03 ( 0.96, 1.11 ) | 0.40 | 1.09 ( 0.83, 1.43 ) | 0.55 | |

| Marital status | Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Not married | 1.00 ( 0.97, 1.02 ) | 0.88 | 0.87 ( 0.79, 0.97 ) | 0.01 | |

| Unknown | 0.97 ( 0.95, 1.00 ) | 0.02 | 0.92 ( 0.84, 1.01 ) | 0.07 | |

| State buy-in | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.99 ( 0.96, 1.02 ) | 0.43 | 0.82 ( 0.72, 0.93 ) | <.01 | |

| Urban/Rural | Big Metro | Reference | Reference | ||

| Metro | 0.98 ( 0.94, 1.01 ) | 0.18 | 1.10 ( 0.96, 1.27 ) | 0.18 | |

| Urban | 0.98 ( 0.93, 1.02 ) | 0.30 | 1.11 ( 0.93, 1.32 ) | 0.24 | |

| Less urban | 0.97 ( 0.94, 1.01 ) | 0.15 | 1.01 ( 0.87, 1.18 ) | 0.86 | |

| Rural | 0.99 ( 0.92, 1.07 ) | 0.87 | 1.19 ( 0.89, 1.59 ) | 0.24 | |

| Cancer stage | Stage II | Reference | |||

| Stage III | 1.02 ( 1.00, 1.04 ) | 0.03 | NA | ||

| Tumor grade | I | Reference | Reference | ||

| II | 1.02 ( 0.98, 1.06 ) | 0.37 | 1.07 ( 0.90, 1.26 ) | 0.47 | |

| III | 1.02 ( 0.97, 1.06 ) | 0.47 | 1.12 ( 0.94, 1.34 ) | 0.21 | |

| IV | 1.05 ( 0.94, 1.16 ) | 0.39 | 1.04 ( 0.70, 1.57 ) | 0.83 | |

| unknown | 0.99 ( 0.93, 1.06 ) | 0.84 | 1.03 ( 0.80, 1.32 ) | 0.82 | |

| Tumor size(mm) | 0–31 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 32–44 | 1.03 ( 1.00, 1.06 ) | 0.02 | 0.99 ( 0.90, 1.09 ) | 0.87 | |

| 45–59 | 1.04 ( 1.01, 1.07 ) | <.01 | 1.00 ( 0.89, 1.11 ) | 0.94 | |

| ≥60 | 1.06 ( 1.03, 1.09 ) | <.01 | 1.00 ( 0.89, 1.11 ) | 0.98 | |

| Unknown | 1.00 ( 0.96, 1.04 ) | 0.85 | 0.85 ( 0.73, 1.00 ) | 0.05 | |

| Surgery type | Conventional | Reference | Reference | ||

| Laparoscopic | 1.00 ( 0.98, 1.03 ) | 0.78 | 0.96 ( 0.87, 1.07 ) | 0.48 | |

| Surgeon specialty | General surgeon | Reference | Reference | ||

| Specialty* | 1.04 ( 1.01, 1.07 ) | <.01 | 0.99 ( 0.90, 1.10 ) | 0.89 | |

| Other | 1.02 ( 0.97, 1.07 ) | 0.54 | 0.85 ( 0.69, 1.04 ) | 0.12 | |

| Unknown | 1.01 ( 0.98, 1.04 ) | 0.60 | 0.92 ( 0.80, 1.06 ) | 0.26 | |

| Charlson comorbidity | 0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 1 | 1.00 ( 0.98, 1.02 ) | 0.91 | 0.92 ( 0.85, 1.01 ) | 0.09 | |

| >1 | 0.99 ( 0.97, 1.02 ) | 0.66 | 0.80 ( 0.70, 0.91 ) | <.01 | |

| Diagnosis year | 2001 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2002 | 1.02 ( 0.98, 1.06 ) | 0.40 | 1.04 ( 0.88, 1.23 ) | 0.64 | |

| 2003 | 1.00 ( 0.96, 1.05 ) | 0.85 | 1.01 ( 0.86, 1.20 ) | 0.89 | |

| 2004 | 1.06 ( 1.02, 1.11 ) | 0.01 | 1.05 ( 0.88, 1.24 ) | 0.61 | |

| 2005 | 1.06 ( 1.02, 1.11 ) | <.01 | 1.21 ( 1.03, 1.42 ) | 0.02 | |

| 2006 | 1.11 ( 1.07, 1.16 ) | <.01 | 1.17 ( 0.99, 1.39 ) | 0.06 | |

| 2007 | 1.15 ( 1.10, 1.20 ) | <.01 | 1.10 ( 0.92, 1.33 ) | 0.30 | |

| 2008 | 1.15 ( 1.10, 1.21 ) | <.01 | 1.01 ( 0.83, 1.23 ) | 0.91 | |

| 2009 | 1.16 ( 1.11, 1.21 ) | <.01 | 1.21 ( 1.01, 1.45 ) | 0.04 | |

| 2010 | 1.17 ( 1.11, 1.22 ) | <.01 | 1.18 ( 0.97, 1.42 ) | 0.09 | |

| 2011 | 1.16 ( 1.11, 1.22 ) | <.01 | 1.23 ( 1.02, 1.49 ) | 0.03 |

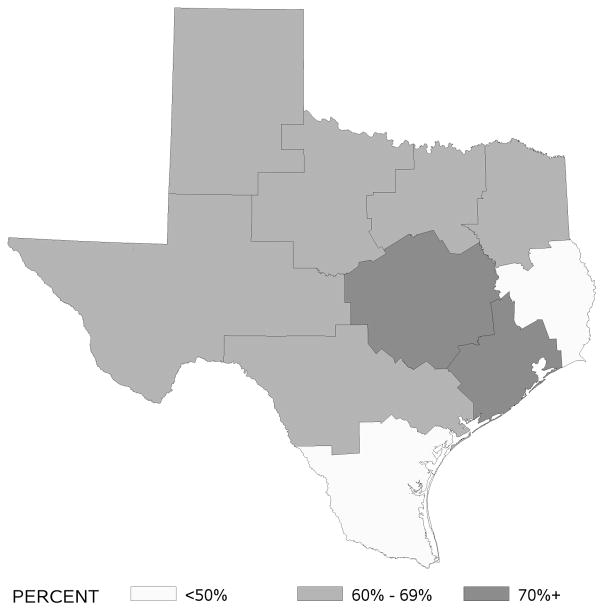

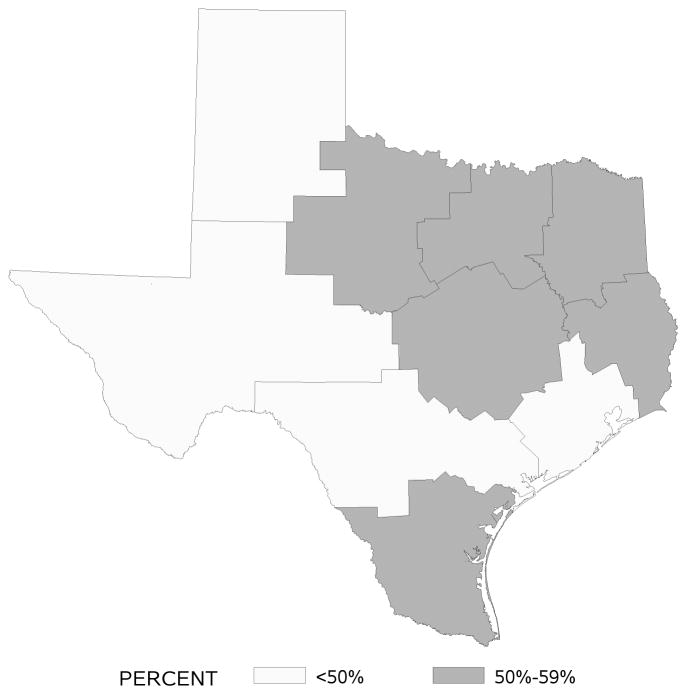

Rates of SA and C based on patients’ residence area by Health Services Region are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. SA rates were highest in regions that included large cities like Houston, Austin, and Dallas (e.g., > 70% in the Houston area). In contrast, C rates were not high in any one particular region of Texas with range from 45% to 57%.

Figure 1.

Adherence rates to surgical removal of at least 12 nodes by Texas Health Services Region

Figure 2.

Adherence rates to adjuvant chemotherapy by Texas Health Services Region

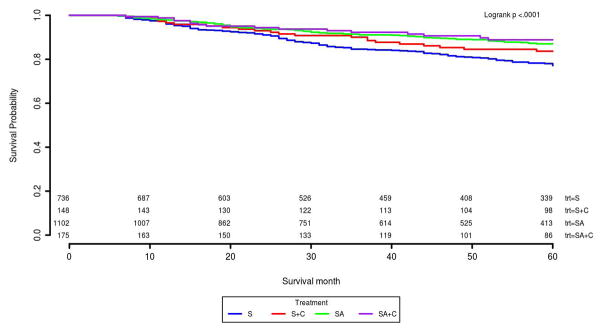

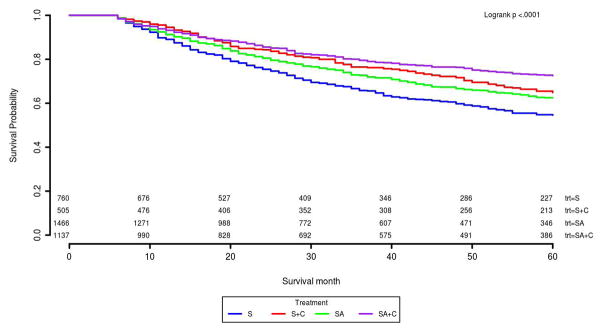

About 51% of stage II and 30% of stage III patients received stage-specific guideline recommended treatment (Table 3). For stage II patients, SA had the best 5-year survival rate of 87% compared with S of 77% and S+C of 84% (Table 3 and Figure 3). This survival benefit persisted after adjusting for other covariates and IPTW in the Cox model. The HR and its 95% CI for S and S+C was 1.94 (1.50, 2.50), 1.75 (1.08, 2.84) compared with SA patients (Table 4). For stage III, we found chemotherapy was significantly associated with better survival compared with surgery only patients. SA+C patients had the highest survival probability (73%) among four treatment groups. In Kaplan-Meier survival curves, S+C was slightly better than SA patients (Figure 4). Although S+C patients had lower 5-year survival rate compared with SA+C, these patients had similar risk of cancer caused death in the Cox model adjusted for covariates and IPTW (Table 3 and Figure 4). Other factors such as age, race, tumor size, and surgery type etc., were also found significantly associated with risk of death for stage II or III in the final Cox model (Supplemental Table 3). The proportional hazard assumptions for the final Cox model was satistifed for both the stage II and III patients.

Table 3.

Stage-specific treatment adherence and five-year colon cancer specific survival probability for stage II or III colon cancer patients

| Treatment* | Stage II (N=2161)

|

P* | Stage III (N=3868)*

|

P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Survival probability | N (%) | Survival probability | |||

| S | 736 (34.06) | 77% | <.01 | 760 (19.65) | 55% | <.01 |

| S+C | 148 (6.85) | 84% | 0.02 | 505 (13.06) | 65% | <.01 |

| SA | 1102 (50.99) | 87% | Reference | 1466 (37.90) | 62% | <.01 |

| SA+C | 175 (8.10) | 89% | 0.18 | 1137 (29.40) | 73% | Reference |

Abbreviations: S= non-adherent surgery (i.e., less than 12 lymph nodes removed); C= adjuvant chemotherapy; SA= surgery adherence to guidelines

Stage III*: included patients who were older than 80 years

P* is the p-value of log-rank test.

Figure 3.

Five year cause-specific survival curves for 2161 stage II colon cancer patients

Abbreviations: S= non-adherent surgery; C= adjuvant chemotherapy; SA= surgery adherence to guidelines

Table 4.

Association of adherence to treatment and cancer cause specific mortality among stage II or III colon cancer patients

| Treatment | Stage II Hazard ratio* (95% CI) |

P* | Stage III Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 1.94 ( 1.50, 2.50 ) | <.01 | 1.72 ( 1.45, 2.05 ) | <.01 |

| S+C | 1.75 ( 1.08, 2.84 ) | 0.02 | 1.16 ( 0.94, 1.43 ) | 0.16 |

| SA | Reference | 1.32 ( 1.13, 1.54 ) | <.01 | |

| SA+C | 1.31 ( 0.84, 2.04 ) | 0.23 | Reference |

Hazard ratios* and p-values* were from the final Cox model adjusted for other covariates and IPTW.

Abbreviations: S= non-adherent surgery; C= adjuvant chemotherapy; SA= surgery adherence to guidelines

Figure 4.

Five year cause-specific survival curves for 2161 stage II colon cancer patients

Abbreviations: S= non-adherent surgery; C= adjuvant chemotherapy; SA= surgery adherence to guidelines

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that adherence to surgical guidelines increased over time from 2001 to 2011, yet adherence to chemotherapy guidelines has not increased substantially. Patients who received stage-specific guideline-recommended therapy had better five-year CSS compared to patients whose treatment differed from the guidelines.

Our study is the first one that estimated the stage-specific treatment adherence rates for older colon cancer patients according to colectomy with lymphadenectomy of at least 12 lymph nodes and chemotherapy. Earlier studies that evaluated stage-specific adherence rates based on National Cancer Data Base or Medicare data linked with cancer registry data had found a 67% adherence rate for stage II patients and an adherence rate ranging from 40%–50% for stage III patients [1, 12]; these values are slightly higher than our findings. This may be due to those studies using colectomy as the criterion for surgery adherence without evaluating the number of lymph nodes removed. Using SA to evaluate the surgery or chemotherapy treatment effect is important since this criterion is significantly associated with better survival outcomes.

This study identified potential modifiable factors that may improve colon cancer patients’ survival. We found that patients who operated on by a colorectal specialist surgeon were 15% more likely to have SA than patients operated on by a general surgeon. This result is consistent with a study by Jeganathan et al, which revealed a 14% increase in SA when treatment was performed by a colorectal specialist surgeon compared to a general surgeon [13]. Thus, hospitals or health care facilities should provide resources to improve general surgeons’ knowledge and techniques to provide guideline-recommended care to patients since only 14% of colon cancer patients underwent surgery with a colorectal surgeon in Jeganathan’s study[13]. We also found that low-income patients enrolled in Medicare state buy-in programs were 18% less likely to receive guideline-concordant chemotherapy treatment compared with non-buy-in enrollees. The Medicare state buy-in program is eligible for low income individuals with income of 135% or less of the poverty line. This disparity in chemotherapy receipt for low income patients may be due to buy-in patients not being as physically or mentally fit as non-buy-in patients to receive chemotherapy. It may also be due to a lack of oncologists that accept state buy-in patients since reimbursement for patients’ cost sharing by the state buy-in program are low compared to that of non-buy-in patients [14]. The latter should encourage Texas healthcare policy makers to identify resources to improve chemotherapy reimbursement so more oncologists would be willing to accept state buy-in patients.

Our study has a number of strengths. It is the first study to describe the SA and C trend for colon cancer patients ≥ 66 years in Texas. It is a large population-based cohort, which allowed various subgroup analyses to evaluate the survival benefit for patients who had adherent vs non-adherent treatment. Although AJCC staging information was not available for patients diagnosed before 2006, we conducted a sensitivity analysis among patients who had AJCC staging and the concordance rates were above 90% for both stage II and III. There are several limitations to the study. Since our study focused on Texans who were older than 65 years, the results may not be generalizable to patients in other states or those 65 years of age or younger. We selected patients who survived for at least six months after diagnosis which excludes individuals who were too sick to receive treatment or patients who did not survive surgery or chemotherapy treatment within six months of its administration; this may have led to an overestimation of the adherence rates since our cohort included relatively healthier patients. This study did not assess potential confounding factors such as patients’ frailty and performance status, preferences or physical and mental resilience, which may have affected their choice of treatment and survival.

Our future work will focus on validating the stage-specific treatment adherence rates in older Medicare patients using a larger sample.

Conclusion

In Texas from 2001 to 2011, 64.4% of colon cancer patients had SA and thus had guideline-concordant treatment. During the same period, 50.3% of stage III patients aged 80 years or younger received adjuvant chemotherapy per the recommended guidelines. Patients who received stage-specific adherent treatment had significant better survival than those with non-adherent treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gary M. Deyter for editing the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the Texas cancer registries, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and Information Management Services, Inc. in the creation of the TCR-Medicare data.

FUNDING

This research was supported in part by grants (RP140020 and RP130051) from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, the Duncan Family Institute, and by Cancer Center Support Grants (CCSGs) for National Cancer Institute-designated Cancer Centers 2P30 CA016672.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: H. Zhao, M. Chavez-MacGregor, S.H. Giordano

Development of methodology: H. Zhao, V. Ho, D. Zorzi, and X. Du

Analysis and interpretation of data: N. Zhang, M. Ding, W. He, J. Niu, M. Yang

Administrative, technical, or material support: S.H. Giordano

References

- 1.Boland GM, et al. Association between adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network treatment guidelines and improved survival in patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(8):1593–601. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(NCCN)., N.C.C.N. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Colon Cancer. 2017 [cited 2017 February 23]; Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf.

- 3.Andre T, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(19):3109–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haller DG, et al. Phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in high-risk stage II and III colon cancer: final report of Intergroup 0089. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8671–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chagpar R, et al. Adherence to stage-specific treatment guidelines for patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(9):972–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colorectal Cancer in Texas: A Closer Look. 2010:21. ]. Available from: www.cprit.state.tx.us/images/uploads/report_colorectal_a_closer_look.pdf.

- 7.Warren JL, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlson ME, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klabunde CN, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–67. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho V, et al. Regional differences in recommended cancer treatment for the elderly. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:262. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1534-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins AS, Chao SY, Fonseca VP. What’s the relative risk? A method to directly estimate risk ratios in cohort studies of common outcomes. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(7):452–4. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanoff HK, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival of patients with stage III colon cancer diagnosed after age 75 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2624–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeganathan AN, et al. Colorectal Specialization Increases Lymph Node Yield: Evidence from a National Database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(7):2258–65. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren JL, et al. Receipt of chemotherapy among medicare patients with cancer by type of supplemental insurance. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(4):312–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.