Abstract

Background

Although larger social networks have been associated with lower all-cause mortality, few studies have examined whether social integration predicts survival outcomes among colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. We examined the association between social ties and survival after CRC diagnosis in a prospective cohort study.

Methods

Participants included 896 women in the Nurses’ Health Study who were diagnosed with stage I, II, or III CRC between 1992 and 2012. Social integration was assessed every 4 years since 1992 using the Berkman-Syme Social Networks Index that included marital status, social network size, contact frequency, religious participation, and other social group participation.

Results

There were 380 total deaths, 167 due to CRC, during follow-up. In multivariable analyses, women who were socially integrated before diagnosis had a subsequent reduced risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 0.65; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46–0.92) and CRC mortality (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.38–1.06) compared with women who were socially isolated. In particular, women with more intimate ties (family and friends) had lower all-cause mortality (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.42–0.88) and CRC mortality (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.34–1.03) compared with those with few intimate ties. Participation in religious or community activities was not related to outcomes. The analysis of post-diagnosis social integration yielded similar results.

Conclusions

Socially integrated women had better survival after diagnosis of CRC, possibly due to beneficial caregiving from their family and friends. Interventions aimed at strengthening social network structures to ensure access to care may be valuable programmatic tools in the management of CRC.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, survival, social networks, social support, mortality, women’s health

Introduction

Over four decades of research have established that stronger social relationships predict lower all-cause mortality,1–4 and the health risks associated with social isolation are comparable to traditional risk factors, such as smoking, blood pressure, and obesity.3,5 Large social networks may improve survival through biological pathways, including neuroendocrine and immunologic changes that influence tumor progression, and through increased instrumental support, including assistance in getting to medical appointments, reminders to take medications, and help with nutrition and mobility.1,6,7 Greater social integration, defined as participation in a broad range of intimate and extended social relationships,6,8 has been associated with lower overall mortality in healthy populations2 and in disease-specific populations, particularly breast cancer patients.9–15 However, few studies have examined this association in other cancer sites.7

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed and second leading cause of cancer death in the US.16 Although marital status has been shown to predict CRC-specific and all-cause mortality among CRC patients,17,18 less is known about the association between social integration and mortality among CRC patients.19–21 In the only study that examined this association, Goodwin et al.20 did not find a relationship between post-diagnosis social integration and all-cause mortality in 211 CRC patients who were followed for up to 10 years. However, this study was limited by a small sample and lack of information on CRC-specific mortality. Given the knowledge gap due to the paucity of research, more studies are needed to determine the potential influence of social relationships on CRC survival outcomes, which would inform a general effect of social networks.7

We therefore examined the association between social integration and all-cause and CRC-specific mortality among 896 CRC patients with up to 22 years of follow-up in the Nurses’ Health Study. Given the theorized health benefits of stronger social networks, we hypothesized that greater social integration would be associated with better survival after CRC diagnosis. We also examined whether social-emotional support, as indicated by the presence and availability of a confidant,11,22 was associated with outcomes, since one study found that low social support was associated with higher risk of CRC mortality in Japanese men but not women.22 However, some evidence suggests that having a large social network is more predictive of survival among cancer patients than social support.14

Patients and Methods

Study Population

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) is a prospective cohort study of 121,700 US female nurses who were between 30 and 55 years of age when the study began in 1976. Since then, participants have received biennial mailed questionnaires about their medical and health behavior history, with each follow-up having at least a 90% response rate. Social networks questions were added in 1992, which we considered baseline in this study, and subsequently collected in 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012. The study population consisted of 896 women who were diagnosed with stages I, II, or III colorectal adenocarcinoma between 1992 and 2012 and who responded to social integration questions prior to diagnosis. Women who had a prior cancer diagnosis other than non-melanoma skin cancer were excluded. Among these 896 women who had pre-diagnosis measurements of social integration, 668 women completed social integration questions after diagnosis and were included in post-diagnosis analyses. Participants were followed until death or June 30, 2014, whichever occurred first. The institutional review board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA) approved the study, and all study participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

Measurement of social integration

Social integration was measured every 4 years since 1992 by the Berkman-Syme Social Networks Index (SNI).23 The seven-item index is a composite measure of four types of social connection: marital status; frequency and number of contacts with close relatives and friends; religious service attendance; and participation in other social groups. The responses to these items yield a total score from 1 to 12 that is typically analyzed as a four-level categorical variable, ranging from I (socially isolated) to IV (socially integrated). The validity of the SNI has been demonstrated previously.24–26 Women in the lowest category of social integration (the most socially isolated) were the reference group. In addition, we examined social network changes before and after diagnosis. Women were defined as having declining or increasing networks versus no change (reference group).

We also considered the association of outcomes with both intimate ties, including marriage and close relatives and friends (sociability), and extended ties, including participation in religious and other social groups.27,28 The intimate ties score ranged from I (not married and low sociability) to III (married and high sociability), and the extended ties score ranged from I (no religious or other social group participation) to IV (both religious and other social group participation).

Measurement of social-emotional support

Similar to Kroenke et al.,11 we assessed pre-diagnosis social-emotional support using two items: the presence and availability of a confidant. Women were asked whether they have a close confidant (yes or no) and, if so, how often they talk with their confidant. We created an indicator variable from these two questions. Categories included: no confidant (reference group), communicate with confidant once/mo or less, communicate with confidant more than once/mo but less often than once/wk, communicate with confidant more than once/wk but less often than once/d, and communicate with confidant once/d or more. Questions were asked in 1992 and every 4 years thereafter until 2012, with the exception of 1996. The correlation between presence and availability of a confidant and social integration was low (r = .09, P < .01).

Measurement of CRC

On biennial mailed questionnaires, participants were asked to self-report diagnoses, including CRC. With participant permission, physicians blinded to exposure information reviewed medical and pathology records to confirm incident CRC and abstract information on the cancer’s anatomic location, stage, and histologic type. CRC was defined according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). CRC was further classified into colon cancer (ICD-9 codes 153.0–153.4, 153.6 to 153.9) and rectal cancer (ICD-9 codes 154.0 or 154.1).

Measurement of mortality

Deaths were ascertained using reports from family or postal authorities and the US National Death Index, which has been shown to have 98% sensitivity and 100% specificity for death ascertainment.29 Date of death was determined from death certificates, and physician reviewers classified individual causes of death. Based on cause of death, we defined CRC mortality as death from CRC and all-cause mortality as death from any cause.

Measurement of covariates

Biomedical and lifestyle factors, including body mass index (BMI), smoking, and aspirin use, have been self-reported biennially. Physical activity and diet have been self-reported every 4 years.

Statistical Analyses

Participants contributed person-years from the date of diagnosis until death or the end of follow-up (June 30, 2014), whichever came first. Follow-up ranged from 0 to 22 years, with a median of 9.5 years. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess associations of social networks most recent to and before diagnosis with time to CRC death and all-cause mortality. We focused on the analysis of social networks before diagnosis to increase power, ensure appropriate time order of exposures and outcomes, and avoid biases that may occur if women with late-stage disease are less likely to fill out later social network questionnaires.11 This is particularly appropriate since social networks tended to be stable from before to after CRC diagnosis (r = .69; P < .001 in our sample). We also examined post-diagnosis social networks and pre- to post-diagnosis changes in social networks in relation to outcomes. In addition, we assessed the association of the presence and availability of a confidant before diagnosis with outcomes. We did not examine change in the presence and availability of a confidant because it was not measured at all time points. We tested the proportional hazards assumption by likelihood ratio tests comparing models with and without interaction terms of age with the predictors, and observed no evidence of violation.

We modeled the medians within each category of social integration to test for linear trends across the categories. Initial models were adjusted for age at diagnosis. We compared these initial models to a second set of models that were adjusted for the following: age at diagnosis (continuous), date of diagnosis (continuous), race/ethnicity (white, black, other), smoking status (never, past, current), alcohol intake (none, 0.1 to <5, 5 to <15, or ≥15 g/d), aspirin use (nonuser, current user), physical activity (quintiles), and BMI (<21, 21 to <23, 23 to <25, 25 to <29, or ≥29 kg/m2). We further adjusted for cancer stage (I, II, III), histologic grade (well differentiated, moderately, poorly, missing/unknown), and cancer site (proximal, distal, rectum, missing/unknown) to assess the association independent of these strong predictors of survival. For pre-diagnosis analysis, information on social integration, smoking, alcohol intake, aspirin use, physical activity, and BMI was taken from the questionnaires closest in time prior to diagnosis. For post-diagnosis analysis, variables were taken from the questionnaires closest in time after diagnosis. In addition, we used Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test to compare CRC-specific and overall mortality according to social integration categories.

We also conducted stratified analyses by age at diagnosis, BMI, cancer stage, and cancer site. Interaction terms were computed based on the cross-product of each dichotomized stratification variable and the continuous social integration variable. When analyses suggested differences in associations across strata, we evaluated interaction terms using Wald chi-square tests. All statistical analyses were done with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). All significance tests were two-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Between 1992 and 2012, 896 women were diagnosed with CRC. Characteristics of women diagnosed with CRC, according to their social integration category prior to diagnosis, are provided in Table 1. Approximately 10.7% (n = 96) of participants were in the lowest category of social integration prior to diagnosis, while 33.4% (n = 299) of participants were in the highest category of social integration. Compared with the most socially integrated women, socially isolated women were more likely to be current smokers and were less physically active.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 896 Women with Stage I, II, or III Colorectal Cancer, by Social Integration Category Prior to Diagnosisa

| Social Integration Category

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (Lowest) (n = 96) |

II (n = 358) |

III (n = 143) |

IV (Highest) (n = 299) |

|

| Age at diagnosis, M (SD), y | 69.9 (8.0) | 71.7 (7.6) | 67.8 (7.9) | 68.4 (6.5) |

| White, % | 93.4 | 93.1 | 89.5 | 97.6 |

| Current smoking, % | 18.8 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 7.7 |

| Alcohol intake, M (SD), g/d | 6.4 (12.2) | 5.4 (10.2) | 6.3 (10.0) | 5.2 (9.1) |

| Aspirin use, % | 50.0 | 48.6 | 49.7 | 44.5 |

| Physical activity, M (SD), METs/wk | 11.2 (18.8) | 15.2 (21.9) | 20.1 (53.9) | 18.8 (21.5) |

| Body mass index, M (SD), kg/m2 | 27.2 (5.6) | 26.8 (5.4) | 26.7 (5.3) | 26.9 (5.7) |

| Stage | ||||

| Stage I, % | 20.8 | 31.0 | 39.9 | 29.1 |

| Stage II, % | 42.7 | 36.9 | 32.9 | 39.8 |

| Stage III, % | 36.5 | 32.1 | 27.3 | 31.1 |

| Grade | ||||

| Well differentiated, % | 9.4 | 10.6 | 13.3 | 13.0 |

| Moderately differentiated, % | 59.4 | 63.7 | 67.8 | 65.2 |

| Poorly differentiated, % | 28.1 | 17.6 | 12.6 | 16.1 |

| Missing/Unknown, % | 3.1 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 5.7 |

| Site | ||||

| Proximal colon, % | 49.0 | 54.5 | 50.3 | 52.5 |

| Distal colon, % | 20.8 | 27.7 | 24.5 | 27.8 |

| Rectum, % | 30.2 | 17.0 | 25.2 | 19.7 |

| Missing/Unknown, % | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Abbreviations: METs, metabolic equivalents; BMI, body mass index.

Except for age at diagnosis, variables were standardized to the age distribution of the study population. Values of polytomous variables may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

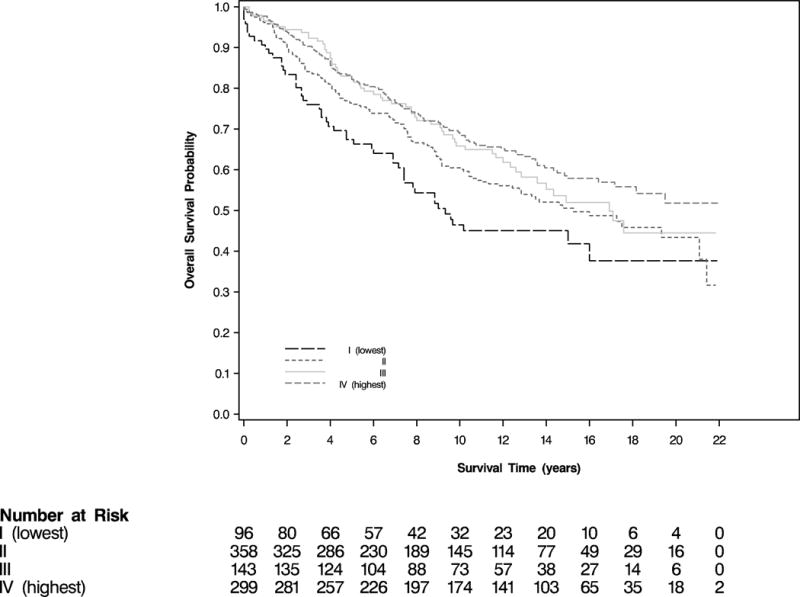

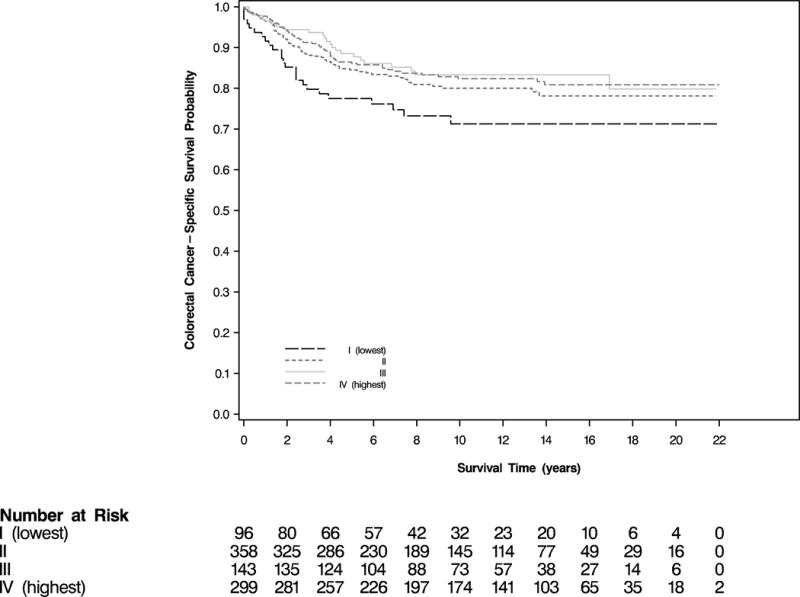

Among the 896 women diagnosed with CRC between 1992 and 2012, there were 380 total deaths, 167 due to CRC. Social integration before diagnosis was associated with a significant reduction in overall mortality (log-rank P = .002; Figure 1). Women who were the most socially integrated were significantly less likely to die from any cause compared with women who were socially isolated (multivariable hazard ratio [HR], 0.65; 95% CI, 0.46–0.92; Table 2). In addition, greater social integration was also associated with a reduction in CRC-specific mortality, although this was not statistically significant (log-rank P = .08; Figure 2); the multivariable HR associated with the highest social integration was 0.63 (95% CI, 0.38–1.06; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Overall Survival According to Category of Social Integration Prior to Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis (log-rank P = .002)

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios (95% CI) of Mortality, by Social Integration Category Prior to Diagnosis

| Social Integration Category

|

Ptrend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (Lowest) (n = 96) |

II (n = 358) |

III (n = 143) |

IV (Highest) (n = 299) |

||

| All-cause mortality | 51 | 155 | 59 | 115 | |

| Age-adjusted | Ref | 0.65 (0.47–0.90) | 0.64 (0.44–0.93) | 0.54 (0.39–0.76) | 0.002 |

| Multivariable model 1 | Ref | 0.72 (0.52, 1.00) | 0.72 (0.49, 1.06) | 0.61 (0.43, 0.86) | 0.01 |

| Multivariable model 2 | Ref | 0.75 (0.54–1.05) | 0.78 (0.53–1.16) | 0.65 (0.46–0.92) | 0.03 |

| Colorectal cancer deaths | 25 | 67 | 23 | 52 | |

| Age-adjusted | Ref | 0.66 (0.42–1.05) | 0.53 (0.30–0.93) | 0.56 (0.35–0.91) | 0.04 |

| Multivariable model 1 | Ref | 0.66 (0.41, 1.06) | 0.52 (0.29, 0.92) | 0.54 (0.33, 0.88) | 0.02 |

| Multivariable model 2 | Ref | 0.73 (0.45–1.20) | 0.61 (0.33–1.11) | 0.63 (0.38–1.06) | 0.11 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Multivariable model 1 was adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), race/ethnicity (white [ref], black, other), smoking status (never [ref], past, current), alcohol intake (none [ref], 0.1 to <5, 5 to <15, or ≥15 g/d), aspirin use (nonuser [ref], current user), physical activity (quintiles), and body mass index (<21 [ref], 21 to <23, 23 to <25, 25 to <29, or ≥29 kg/m2).

Multivariable model 2 was further adjusted for cancer stage (I [ref], II, III), cancer grade (well differentiated [ref], moderately, poorly, missing/unknown), and cancer site (proximal [ref], distal, rectum, missing/unknown).

Figure 2.

Colorectal Cancer-Specific Survival According to Category of Social Integration Prior to Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis (log-rank P = .08)

The social integration components before diagnosis were also examined separately (Table 3). Compared with the lowest intimate ties score, having more intimate ties (i.e., being married and having a large number of friends or relatives seen frequently) was associated with lower all-cause mortality (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.42–0.88) and CRC-specific mortality (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.34–1.03). In addition, being married was significantly associated with lower all-cause mortality (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.42–0.88). Extended social ties (religious service attendance and other social group participation) were unrelated to outcomes.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios (95% CI) of Mortality, by Social Integration Components

| N | Cause of Death

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Cause

|

Colorectal Cancer

|

||||

| Deaths | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Deaths | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | ||

| Intimate ties scorea | |||||

| I (lowest) | 346 | 162 | Ref | 73 | Ref |

| II | 445 | 181 | 0.97 (0.77–1.21) | 77 | 0.88 (0.63–1.24) |

| III (highest) | 105 | 37 | 0.61 (0.42–0.88) | 17 | 0.59 (0.34–1.03) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Not married | 291 | 150 | Ref | 60 | Ref |

| Married | 605 | 230 | 0.76 (0.61–0.95) | 107 | 0.86 (0.61–1.21) |

| Relatives and friends score | |||||

| I (lowest) | 134 | 60 | Ref | 32 | Ref |

| II | 622 | 263 | 0.99 (0.74–1.32) | 112 | 0.74 (0.49–1.12) |

| III (highest) | 140 | 57 | 0.81 (0.55–1.20) | 23 | 0.58 (0.33–1.02) |

| Extended ties scoreb | |||||

| I (lowest) | 218 | 99 | Ref | 46 | Ref |

| II | 165 | 62 | 0.77 (0.55–1.07) | 24 | 0.69 (0.41–1.15) |

| III | 117 | 54 | 0.84 (0.60–1.19) | 22 | 0.65 (0.37–1.11) |

| IV (highest) | 396 | 165 | 0.93 (0.71–1.21) | 75 | 0.94 (0.63–1.40) |

| Religious service attendance | |||||

| Less than once per wk | 383 | 161 | Ref | 70 | Ref |

| At least once per wk | 513 | 219 | 1.02 (0.82–1.28) | 97 | 1.00 (0.72–1.41) |

| Social group participation | |||||

| None | 335 | 153 | Ref | 68 | Ref |

| Any number of hours (>0) | 561 | 227 | 0.91 (0.72–1.15) | 99 | 1.03 (0.73–1.47) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Models were adjusted for variables indicated in Table 2, Multivariable model 2.

In stratified analyses, high social integration before diagnosis was significantly associated with reduced all-cause (HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.25–0.63) and CRC-specific mortality (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.16–0.73) among women who were older than 70 (the mean age at diagnosis) but not among those who were younger, although the interaction term was statistically significant for all-cause mortality only (P = .03; Supporting Table 1 [see online supporting information]). No statistically significant interactions were observed for BMI, cancer stage, or cancer site.

Effect estimates from analyses of post-diagnosis social integration and outcomes were similar to those from pre-diagnosis analyses. High social integration after diagnosis was associated with reduced all-cause (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.37–0.88; Ptrend = .01) and CRC-specific mortality (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.25–1.15; Ptrend = .19), compared with low social integration (Supporting Table 2 [see online supporting information]).

The presence and availability of a confidant was not associated with all-cause or CRC-specific mortality (data not shown). The majority of women (64%) had no change in social networks from pre- to post-diagnosis (Supporting Table 3 [see online supporting information]). Compared to women whose social networks did not change, those whose networks declined had higher, albeit not statistically significant, risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.94–1.73) and CRC-specific mortality (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.73–2.21). Women whose social networks increased had a reduced risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.48–1.10) and CRC-specific mortality (HR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.20–0.92). However, from pre- to post-diagnosis, only 8% of women had a decrease and 3% had an increase of more than one level.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, women with high levels of social integration before CRC diagnosis had significantly reduced risk of all-cause and CRC-specific mortality, particularly among older women. Although the presence and availability of a confidant and the number of extended ties were not associated with survival, having more intimate ties was associated with a significantly lower death rate. Effect estimates were similar in analyses of post-diagnosis social networks. Women whose social networks increased from pre- to post-diagnosis had a significantly reduced risk of CRC-specific mortality.

To our knowledge, only one study has examined the association between social integration, as measured by the SNI, and mortality among CRC patients,20 and it did not find an association between post-diagnosis social integration and overall survival (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.6–1.9). However, this study was relatively small (211 CRC patients). In comparison, the current study had more patients and adjusted for additional confounding factors including CRC severity.

Several pathways were proposed through which social networks may confer improved survival among cancer patients. Some research showed that higher levels of social integration were associated with lower levels of pro-inflammatory markers, such as interleukin-6,6,30 which may directly influence disease progression. In addition, social relationships may reduce psychosocial stress and thereby affect cancer progression by altering the release of glucocorticoids from the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and catecholamines from the sympathetic nervous system, both of which modulate tumor progression.31,32 Moreover, animal models have shown that chronic stress promoted CRC tumor growth and metastasis.33,34 In addition, social networks may influence survival among cancer patients through the provision of instrumental social support before diagnosis (e.g., prompting preventive healthcare) and after diagnosis (e.g., assistance in getting to medical appointments and adhering to medical regimens).6,7 Social networks may also indirectly affect disease progression by influencing health behavior, such as smoking behavior, physical activity patterns, and cancer screening behavior. Socially isolated people may be more likely to engage in poor health behaviors, thereby precipitating cancer progression and its related mortality.14

When we examined the types of social ties, we found that having more intimate ties was associated with better survival among women with a CRC diagnosis, while having more extended ties was not associated with outcomes. Specifically, being married was associated with a significantly reduced all-cause mortality, which is consistent with other studies in CRC patients that have found that being married predicts lower mortality risk.17,18,35 In our sample of women diagnosed with CRC in the NHS, it is possible that women’s spouses acted as their caregivers, providing women with instrumental support (e.g., rides to the hospital, reminders to take medications) that may have improved survival outcomes.1,6,7 Additionally, it has been suggested that the quality of emotional support supplied by a social network, such as that provided by a close confidant, is also important for survival.7,10,22 However, we did not find that the presence and availability of a confidant was associated with overall or CRC survival.

We also found that the association between social integration and survival was present among older women only. It is unclear why older women might have derived greater benefit from their social networks than younger women. A possible explanation is that older women may be more likely to receive instrumental support from their spouses, who may be retired and have the time and resources to provide care. Indeed, a study of breast cancer patients found that marriage had a stronger association with all-cause and breast cancer-specific mortality among older white women than younger white women.12

The current study also has limitations. In general, the NHS lacks diversity in race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status,36 which may limit the results’ generalizability to other populations. Additionally, since the NHS includes only women, we were unable to examine whether gender modifies the association of social integration and CRC survival, and marital status has been shown to have stronger inverse association with CRC survival in men than in women.35 Moreover, since having a confidant is a limited proxy for emotional support from social contacts, we cannot rule out the possibility that social-emotional support may influence survival.

In summary, we found that socially integrated women had better survival after diagnosis of CRC, possibly due to beneficial caregiving from their family and friends. At the time of diagnosis, health care providers may assess women’s social networks to determine whether these networks provide necessary resources and whether external help, e.g., assistance from social workers, is needed to ensure access to care. Interventions aimed at strengthening social network structures may be valuable programmatic tools in the management of CRC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The Nurses’ Health Study is supported by NIH grants UM1CA186107 and P01CA87969. Dr. Bao is supported by NIH grants KL2TR001100 and P30DK046200, and by Department of Defense grant CA150357. Dr. Fuchs is supported by NIH grants P30CA016359, R01CA169141, R01CA118553, and by Stand-Up-to-Cancer.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

Author Contributions: Elizabeth A. Sarma: Interpretation, drafting, revising, and approval of the manuscript. Ichiro Kawachi: Interpretation, revising, and approval of the manuscript. Elizabeth M. Poole: Interpretation, revising, and approval of the manuscript. Shelley S. Tworoger: Interpretation, revising, and approval of the manuscript. Edward L. Giovannucci: Data acquisition and assembly, interpretation, revising, and approval of the manuscript. Charles S. Fuchs: Data acquisition and assembly, interpretation, revising, and approval of the manuscript. Ying Bao: Study conception and design, data acquisition and assembly, analysis, interpretation, drafting, revising, responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis (full access to all the data in the study), and approval of the manuscript.

Women with stronger social networks in the Nurses’ Health Study had better survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. Interventions aimed at strengthening social network structures to ensure access to care may be valuable programmatic tools in the management of colorectal cancer.

References

- 1.Berkman LF. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:245–254. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, et al. A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996;50:245–251. doi: 10.1136/jech.50.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D, Syme SL, Balmes J, Adler N. Social isolation: a predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:2056–2062. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkman LF, Krishna A. Social network epidemiology. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, editors. Social Epidemiology. 2nd. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 234–289. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;75:122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brissette I, Cohen S, Seeman TE. Measuring social integration and social networks. In: Cohen S, Underwood L, Gottlieb B, editors. Measuring and Intervening in Social Support. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 53–85. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beasley JM, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Social networks and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:372–380. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0139-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Boer MF, Ryckman RM, Pruyn JF, Van den Borne HW. Psychosocial correlates of cancer relapse and survival: a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37:215–230. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1105–1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroenke CH, Michael YL, Poole EM, et al. Postdiagnosis social networks and breast cancer mortality in the After Breast Cancer Pooling Project. Cancer. 2017;123:1228–1237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroenke CH, Quesenberry C, Kwan ML, Sweeney C, Castillo A, Caan BJ. Social networks, social support, and burden in relationships, and mortality after breast cancer diagnosis in the Life After Breast Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:261–271. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nausheen B, Gidron Y, Peveler R, Moss-Morris R. Social support and cancer progression: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waxler-Morrison N, Hislop TG, Mears B, Kan L. Effects of social relationships on survival for women with breast cancer: a prospective study. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:177–183. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90178-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansen C, Schou G, Soll-Johanning H, Mellemgaard A, Lynge E. Influence of marital status on survival from colon and rectal cancer in Denmark. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:985–988. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Wilson SE, Stewart DB, Hollenbeak CS. Marital status and colon cancer outcomes in US Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registries: Does marriage affect cancer survival by gender and stage? Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ell K, Nishimoto R, Mediansky L, Mantell J, Hamovitch M. Social relations, social support and survival among patients with cancer. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:531–541. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodwin JS, Samet JM, Hunt WC. Determinants of survival in older cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1031–1038. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.15.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villingshøj M, Ross L, Thomsen BL, Johansen C. Does marital status and altered contact with the social network predict colorectal cancer survival? Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:3022–3027. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda A, Kawachi I, Iso H, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Social support and cancer incidence and mortality: the JPHC study cohort II. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:847–860. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berkman LF, Breslow L. Health and Ways of Living. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodenow C, Reisine ST, Grady KE. Quality of social support and associated social and psychological functioning in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Health Psychol. 1990;9:266–284. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer C, Coyne JC, Lazarus RS. The health-related functions of social support. J Behav Med. 1981;4:381–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00846149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai AC, Lucas M, Kawachi I. Association between social integration and suicide among women in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:987–993. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai AC, Lucas M, Sania A, Kim D, Kawachi I. Social integration and suicide mortality among men: 24-year cohort study of U.S. health professionals. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:85–95. doi: 10.7326/M13-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the National Death Index and Equifax Nationwide Death Search. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:1016–1019. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loucks EB, Sullivan LM, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Larson MG, Berkman LF, Benjamin EJ. Social networks and inflammatory markers in the Framingham Heart Study. J Biosoc Sci. 2006;38:835–842. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, et al. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:240–248. doi: 10.1038/nrc1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutgendorf SK, Andersen BL. Biobehavioral approaches to cancer progression and survival: mechanisms and interventions. Am Psychol. 2015;70(2):186–197. doi: 10.1037/a0035730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Q, Wang F, Yang R, Zheng X, Gao H, Zhang P. Effect of chronic restraint stress on human colorectal carcinoma growth in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao L, Xu J, Liang F, Li A, Zhang Y, Sun J. Effect of chronic psychological stress on liver metastasis of colon cancer in mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3869–3876. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, et al. Origin, methods, and evolution of the three Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1573–1581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.