Abstract

Objective

To examine reasons for seeking abortion services outside the formal healthcare system in Great Britain, where abortion is legally available.

Study Design

We conducted a mixed-methods study among women resident in England, Scotland, and Wales who requested at-home medication abortion through online telemedicine initiative Women on Web (WoW) between November 22nd 2016 and March 22nd 2017. We examined the demographics and circumstances of all women requesting early medication abortion and conducted a content analysis of a sample of their anonymized emails to the service to explore their reasons for seeking help.

Results

Over a 4-month period, 519 women contacted WoW seeking medication abortion. These women were diverse with respect to age, parity, and circumstance. 180 women reported 209 reasons for seeking abortion outside the formal healthcare setting. Among all reasons, 49% were access barriers, including long waiting times, distance to clinic, work or childcare commitments, lack of eligibility for free NHS services, and prior negative experiences of abortion care; 30% were privacy concerns, including lack of confidentiality of services, perceived or experienced stigma, and preferring the privacy and comfort of using pills at home; and 18% were controlling circumstances, including partner violence and partner/family control.

Conclusion

Despite the presence of abortion services in Great Britain, a diverse group of women still experiences logistical and personal barriers to accessing care through the formal healthcare system, or prefer the privacy of conducting their abortions in their own homes. Health services commissioning bodies could address existing barriers if supported by policy frameworks.

Keywords: Abortion, Access, Preference, Great Britain, United Kingdom, Telemedicine

1. Introduction

The landmark 1967 Abortion Act brought legalized abortion to Great Britain, the geographical area comprising England, Scotland, and Wales [1]. As a result, women in Great Britain (hereafter, Britain) are often assumed to have access to available, acceptable, and affordable services, especially when compared to other parts of the United Kingdom and the British Isles, including Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man, where abortion remains illegal under most circumstances [2].

Several key provisions of the Abortion Act, however, as well as additional regulations on service provision may pose impediments to access. First, all abortion requests, irrespective of gestation or procedure type, must be reviewed and approved by two registered practitioners [3]. Both practitioners must complete legal documentation before the procedure can be carried out [3]. Second, both mifepristone and misoprostol for an early medication procedure must be administered at a registered clinical site (misoprostol cannot be taken at home), with a recommended 24–48 hour interval between receipt of each medication [4], although some sites do now offer simultaneous administration. Third, abortions carried out outside the specific provisions of the act are illegal and carry a criminal penalty of penal servitude for life under the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act in England and Wales, and under common law in Scotland [5]. The criminal penalty attached to abortion not conducted according to a specific set of circumstances prohibits telemedicine abortion under current regulatory policy in Britain and also contributes to stigma [6].

Despite these potential barriers, little is known about British women’s experiences accessing abortion. In light of this knowledge gap, we sought to examine the reasons why women in Britain might look for other avenues to abortion care outside the formal healthcare system. Using data from an online telemedicine organization that is not available in Britain, but which nevertheless receives requests for early medication abortion from British women, our objectives are to explore: 1) any barriers women report to accessing services; and 2) their perspectives on self-sourcing their own medication abortions to carry them out at home.

2. Methods

We examined data from Women on Web (WoW), an online non-profit initiative that provides early medication abortion through telemedicine in areas where access to safe abortion is restricted. The service consists of a multilingual, specially trained helpdesk team [7], which receives and handles requests for help from women around the world, and a team of doctors who prescribe mifepristone and misoprostol according to the WHO recommended dosage regimen for medication abortion [8]. A partner organization dispatches the medications to an address provided by the woman. Women make a request for medication abortion by filling out an online consultation form. Further details about the full operation of the service are available elsewhere [7]. While women in Britain are not able to avail of the service, many nonetheless fill out the online consultation form on the WoW website [9] to request medication abortion. Due to a rise in requests from women in Britain, WoW began a new, non-advertised helpdesk service in November 2016, which helps women to explore individually-tailored options in their local and surrounding areas. To avail of this service, women are asked to describe their specific circumstances or reasons for requesting abortion outside of the formal healthcare setting.

We retrieved online consultation forms for all women in Britain who contacted WoW to request medication abortion between November 22nd 2016 and March 22nd 2017. Consultation forms contained information about age, parity, weeks’ gestation at the time of request, any worries regarding feelings about the decision to end the pregnancy, circumstances of pregnancy, and reasons for seeking abortion. We categorized age as “Under 20 years”, and into 5-year increments thereafter, with a final group of “45 years and over”. For gestational age women selected from a list of options (displayed in Table 1). For circumstances of pregnancy and decision to end pregnancy, women could select one or more options from a list and/or write a free text response. Check box and free text responses were integrated and women could choose as many responses as desired (displayed in Table 1). Women could decline to answer any question that did not determine medical eligibility.

Table 1.

Characteristics of British women requesting at-home medication abortion through Women on Web, 22 November 2016 – 22 March 2017 (n=519)

| Reported Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Under 20 | 9.4 |

| 20–24 | 21.4 |

| 25–29 | 24.5 |

| 30–34 | 20.0 |

| 35–39 | 17.3 |

| 40–44 | 5.8 |

| 45 and over | 1.5 |

| Paritya | |

| 0 | 68.9 |

| 1 | 18.5 |

| 2 | 7.1 |

| 3 | 3.0 |

| 4 or more | 2.5 |

| Weeks’ gestation | |

| Fewer than 7 weeks | 76.5 |

| Between 7 and 10 weeks | 23.5 |

| Circumstances of pregnancy | |

| Did not use contraception | 45.1 |

| Contraception used incorrectly or did not work | 51.6 |

| Rape | 3.3 |

| Reasons decided to terminate pregnancyb | |

| I just cannot cope with a child at this point in my life | 67.9 |

| I have no money to raise a child | 39.5 |

| My family is complete | 26.7 |

| I feel I am too young to have a child | 17.2 |

| I want to finish school | 14.7 |

| I feel I am too old to have a child | 6.0 |

| I have health problems | 3.3 |

We examined numbers of women living in Britain requesting abortion in each of the four months since the service began. For all four months combined, we examined age distribution, parity, weeks’ gestation, circumstances of pregnancy, and reason decided to end the pregnancy. For those women who wished to receive further support, including information about clinical services in their local and surrounding area, the emails they sent to the helpdesk describing their circumstances were provided with all potentially identifying personal information removed. Two of the authors independently analyzed the content of the emails and coded them according to an iteratively developed coding guide. Differences were resolved via group discussion using a summative content analysis approach [10]. Each woman reporting more than one reason could be coded under multiple categories.

All data analysis was completed using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp. 2013. College Station, Texas). At the time of accessing the service, women consented to the fully anonymized use of their data for research purposes. The University of Texas Institutional Review Board approved the study.

3. Results

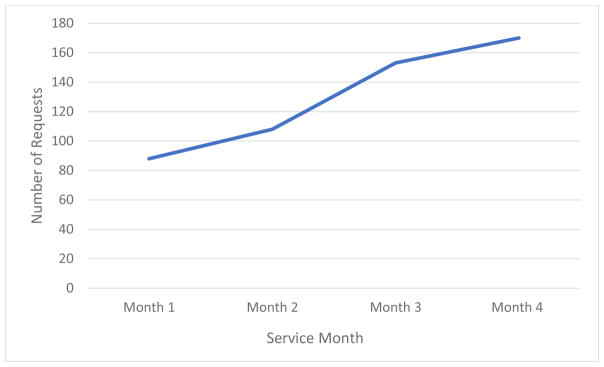

Between November 22nd 2017 and March 22nd 2017, 519 women living in Britain contacted WoW to request medication abortion. Over the first four months of the service, the number of women contacting WoW almost doubled from 88 in the first month to 170 in the fourth month (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Volume of requests from women in Great Britain over the first four months of the new Women on Web Great Britain support service (n=519)

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 519 women who made an online request. Women from all reproductive age groups are represented, with a mean age of 28 years. Sixty-nine percent were nulliparous. At the time of making the request, 77% reported a gestational age of fewer than 7 weeks, with the remaining 23% reporting between 7 and 10 week’s gestation. Slightly over half (52%) had experienced a contraceptive failure, 45% had not being using a method at the time of the pregnancy, and 3% had become pregnant as a result of rape. The most common reason for choosing to end the pregnancy (reported by 68% of women) was not being able to cope with a child at this point in their lives.

Among the 519 women who contacted WoW for help, 180 (35%) wished to receive individually-tailored help accessing clinical services and thus provided further details about their circumstances. Of these, 29 (16%) reported more than one reason, for a total of 209 reasons. We identified several key categories of reasons (Table 2) and discuss each below with illustrative examples from women’s reported experiences. Each woman is assigned a pseudonym to preserve anonymity. For the same reason, we identify women’s location only at the country level. The sample, however, exhibited widespread geographical variation and included women from both urban and rural settings across Britain.

Table 2.

Key categories of circumstances and reasons for accessing abortion services outside the formal healthcare setting in Great Britain (n=209)

| Circumstance/Reason | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Barriers to Accessing in-Clinic Care | 49.3 |

| Waiting Times and multiple appointments | 30.1 |

| Lack of eligibility of free NHS services | 13.4 |

| Inability to make available appointment times due to work or childcare | 9.1 |

| Distance or lack of transport to clinic | 9.1 |

| Prior negative experience with the healthcare system | 2.9 |

| 2. Privacy Concerns and Preferences | 30.1 |

| Perceived or experienced stigma | 12.9 |

| Preference for privacy and comfort of home environment | 8.6 |

| Fear of breach of confidentiality | 8.1 |

| 3. Threat of Violence or Controlling Circumstances | 18.2 |

| Fear or experience of intimate partner violence and control | 11.5 |

| Fear or experience of family control | 6.7 |

| 4. Other | 2.4 |

3.1 Barriers to Accessing In-Clinic Care

The most common reason for seeking abortion services from WoW was experiencing barriers to accessing in-clinic abortion care, representing almost half of all reported reasons (49%). Among these barriers, the most prevalent was experiencing delays in accessing services, including waiting times of several weeks. Amelia, a 34-year-old woman living in England explained: “I’ve been in touch with my doctor and have been referred but they can’t see me for nearly three weeks. I cannot wait that long. I have 9 children who need me and every day is feeling like torture at the minute. My marriage has ended and I cannot physically face another child on my own. I just want to get on with my life and raising the children I do have and who need me now.”

For others, such waiting times would push them over the threshold for a medication abortion. Alison, a 30-year-old woman living in England explained: “I am currently between 7–8 weeks pregnant and want a medical termination however all abortion services in the U.K. are heavily backed up and cannot offer me an appointment for over three weeks. I’ve called every service provider in my area and also gone through my GP. There is a difference between legal and accessible and a wait of a month to terminate pregnancy is much too long. I can’t endure the mental anxiety of staying pregnant for another three weeks and then having a surgical procedure.”

Another common barrier was logistical difficulties getting to a clinic due to inability to get time away from work or childcare to attend one or more appointments. Linda, a 31-year-old working mother living in Scotland echoed many others when she explained: “I am only 2 weeks pregnant, I already have 3 kids and I am a single working mum. I am unable to go to the hospital as I do not have the funds to pay for childcare while I would be in there. I am unable to take time off work and I can’t tell my family so there is no one I can ask to look after the kids. I really need to do this in my own home.”

For other women, major barriers to clinic access were long travel distances or lack of transport. Rachel, a 30-year-old woman living in England explained: “My nearest clinic is over 100 miles away and I have no idea how I would get there and back home after the abortion.” Lisa, who is 25 years old and lives in a different area of England echoed these concerns and explained how they intersect with many of the others barriers previously discussed: “Unfortunately, my local area is somewhat out of the way. I do not drive and cannot afford the public transport to attend the 3–4 appointments that they require to complete the abortion. I also have a young child at home who requires a lot of attention due to being premature. I’m really desperate and I’ve been told there is a 3 week wait, I’m really distressed and I just want the procedure over and done with.”

Women who are ineligible for free, non-emergency NHS services face particular barriers finding and paying for abortion care on their own. Most commonly, these women are either undocumented immigrants, or have been admitted under a visa program and are thus considered visitors to rather than naturalized ordinary residents of Great Britain. Leila, who is 22 years old and living in England explained “I completely lack the money for services and I am not a resident of UK. I am completely alone and really need help.” For many of these women, the minimum cost of an abortion would be approximately £545 [11].

Finally, some women reported prior negative experiences with clinical services or experienced judgmental attitudes from healthcare providers, and were afraid of encountering the same situation a second time. Jessica, who is 27 years old and living in England explained: “I know what is available to me. I’ve had bad experiences in the past. I do not want to talk to anyone or go anywhere. I won’t have a hospital abortion again. I find it ironic that it would be easier for me to get what I need in a country where abortion is illegal!”

3.2 Privacy Concerns, Confidentiality Concerns and Privacy Preferences

Almost one third (30%) of reasons for seeking abortion outside the formal healthcare setting were due to concerns about privacy and confidentiality, and preferences for at-home abortion. Many women wished to keep their abortion secret because of either perceived or experienced stigma around abortion. As Meera, who is 29 years old and lives in England explained: “I’m ashamed and embarrassed to return to clinic as I’ve been for an abortion before and know I will be judged for having another one. The stigma of having to walk into any face-to-face setting is too much.”

Others feared breach of confidentiality if they accessed in-clinic services, sometimes due to working within the hospital or clinic themselves, or having friends or family working there. Some even feared the abortion would be inappropriately disclosed to members of the local community or that someone would see them accessing abortion services and tell others. In many Health Board areas and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCG, a clinically-led statutory NHS body that plans and commissions health care services for a specific area), there is no choice of local service provider to mitigate this potential situation. Samantha, who is 38 years old and lives in Wales described a situation similar to that of other women living in smaller communities “I live in a quite remote town and a family member works at my local doctor’s. I just can’t go there with an unwanted pregnancy looking for an abortion. I am unable to travel anywhere because of care for two other children.”

For other women, issues such as severe anxiety made it hard for them to leave the house, leading to a strong preference or necessity for both consultations and procedures to take place in private at home. Tina, who is 35 years old and lives in England explained: “I am on medication for the depression and anxiety and I struggle to leave the house. I do all my shopping online, my child is picked up and dropped off for school in a taxi. Simple things like leaving the house to take the bins out are an impossible task for me... I know I couldn’t cope with this pregnancy and I certainly wouldn’t be able to cope with a baby but I know I can’t go outside to the doctors and I certainly wouldn’t cope with a hospital visit.”

Other women simply preferred the privacy and comfort of using abortion medications at home. Olivia, a 30-year-old woman living in England said: “I have had one medical abortion 6 years ago and I didn’t like the fact I had to stay in hospital where I wasn’t at all comfortable. I would much rather be in my own home with my partner there to support me.” Some women also commented that they felt they would be better off living in a country where abortion is not legally available so that they could access services from WoW rather than go through the suffering they were experiencing in Britain. For others, a change in law to decriminalize self-sourced and self-managed abortion was the clear solution. Petra, a 38-year-old woman living in England explained: “I can’t agree with the law as it stands because surely allowing a woman to buy the pills as she may buy a ’morning after pill’ would save the NHS so much time and money and resources. I’ve previously had two relatively late terminations due to fetal anomaly. If I could have done it at 5 weeks, it would have been way less traumatic. At the very least, my GP should be able to give me the pills right after I found out I was pregnant.”

3.3 Threat of Violence or Controlling Circumstances

Just over 1 in 6 reasons (18%) involved a situation where women did not feel able to seek abortion services at a clinic or hospital because of the fear or threat of partner violence or a situation involving a controlling family. These circumstances ranged from fear of strong disapproval on religious grounds—leading to shunning or, in extreme circumstances, fear of honor killing—to inability to leave the house without permission from a partner and fear of physical violence from a partner disapproving of abortion. Zara, who is 32 years old and lives in England explained “I’m never allowed to go anywhere alone without my husband or a member of his family escorting me. I don’t have a normal life since getting married. Abortion is against his family’s religion and I’m very anxious what would happen if I was caught.” Anna, who is 35 years old and living in a different part of England echoed many others when she described her terrifying situation: “I have restrictions that could jeopardize my safety here. The pregnancy is a result of adultery. I do not want to defy certain family members and bring shame on them knowing that I depend on them. That would put my life at risk and mean that I would have to flee with no job and no skills. This is beyond doubt the safest option for me.” Susan, who is 30 years old and lives in England, described her situation living with domestic violence and unable to seek care at a clinic or hospital for fear of partner intervention or retaliation: “I’m in a controlling relationship, he watches my every move, I’m so scared he will find out, I believe he’s trying to trap me and will hurt me. I can’t breathe. If he finds out, he wouldn’t let me go ahead, then I will be trapped forever. I cannot live my life like this.”

A small number of reasons (3%) did not fit into any of the categories listed above. These included reasons such as convenience and wanting an early medication abortion even though gestational age was too advanced.

4. Discussion

Our findings indicate that despite the presence of safe, legal abortion services in Britain, these services are not universally accessible. Although almost 198,000 abortions were carried out in Britain in 2016 [12][13], it is clear from our findings that some groups of women still experience particularly challenging, if not impossible, circumstances when seeking abortion access. Challenges highlighted in this study include health system barriers, fear of breach of confidentiality, stigma, and risk of serious consequences for personal safety by attempting to access services. Moreover, some women would simply prefer to manage their abortions in the comfort and familiar environment of their own homes. While we cannot say for sure why the number of women contacting WoW has increased so rapidly since their new helpdesk service began, possible reasons include information sharing between women and changes in provider capacity [14] that may have increased pressure on abortion services in the UK.

Strengths of the study include the ability to access and analyze first-hand information from women who have experienced difficulties accessing abortion in Britain or who hold preferences for at-home management. The main limitations are that women contacting WoW for help are unlikely to represent all British women who experience difficulty accessing abortion services, especially those at later gestations and those who do not have internet access or skills. While 90% of households in Britain have internet access and 88% of British adults use the internet every week either on a computer or smartphone [15], these figures do not necessarily represent those who are homeless, itinerant, or living in other unstable or vulnerable situations. The WoW Great Britain helpdesk has, however, received requests both from homeless and itinerant women. Additionally, while only 35% of the women who contacted WoW elected to describe the reasons why they were seeking assistance, the fact that any woman in a universal healthcare system such as the NHS is experiencing access barriers is cause for concern. Our study is intended only to provide a non-generalizable snapshot of the range of barriers and circumstances women in Britain experience. These findings illustrate multiple access problems, some unique to abortion care, in sufficient detail for healthcare commissioners to begin taking steps to address them.

Prior research has demonstrated barriers encountered by women living in rural or remote areas of Britain, who must travel long distances to access their nearest clinic and who frequently encounter delays in getting an appointment [16][17]. Our results demonstrate that these barriers are not unique to women living in remote areas. Indeed, long waiting times, distances to clinics, and lack of appointments that can accommodate childcare and work commitments indicate a lack of service capacity that is not unique to Britain. In the United States, women living in areas where abortion clinics have been forced to close due to legislative restrictions commonly report lengthy waiting times for appointments [18][19]. Distance and travel issues are shared by women in some Australian states, where remote areas lack local clinics [20], while women in some Canadian provinces face similar barriers with respect to waiting times and multiple appointments [21]. Our findings suggest that service capacity in Britain could be increased through adequate local funding, training more providers, and closer alignment of service availability with demand.

Other reported barriers suggest that publicly available information on locally commissioned service access and patient pathways is lacking. Women must be correctly informed about the necessary steps required to obtain abortion in the clinic setting (e.g. that a consult with a family doctor is not required) and women who cannot access their local services should be informed of available alternatives at the time of trying to make their appointment. NHS Choices, NHS Inform and NHS Direct, the national information services for England, Scotland, and Wales, respectively, that provide advice about healthcare choices in broad geographical areas, could be leveraged to provide precise details of services available at the local CCG level. Another possibility is to set up a connection program, by which a local CCG-identified contact could help advise on particularly complex cases, much as the current WoW helpdesk service for British women operates.

Our results also demonstrate that individual women often experience more than one barrier, which are interrelated and compounding, crossing the boundaries of health and social care. For example, a combination of partner violence, financial difficulty, and multiple appointments may mean that simply locating a nearby local service with a short waiting time is insufficient to ensure access to care. Solutions require an integrated and innovative service that can respond simultaneously to multiple patient needs. Partner abuse may start or escalate during pregnancy [22], and mental health issues, including anxiety may be exacerbated by the stress of an unwanted pregnancy [23]. Our results also reflect previous studies of stigma, finding that internalized negative attitudes from partners, family, and friends may cause women to conceal or delaying seeking abortion [24].

A National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline to set the clinical standard for abortion care in Britain, is currently under development. This guideline will provide the evidence base for service improvements, which in turn will influence clinical regulation. The numerous challenges women report to accessing abortion services in our study highlights the need for clinical care that is women-centered. In particular, women experienced two outdated clinical requirements that presented considerable barriers. First, the requirement of a 24–48hr interval between taking mifepristone and taking misoprostol meant that women had to return to the clinic to receive misoprostol. This practice is no longer supported by updated clinical evidence and should be replaced with either home-use of misoprostol or simultaneous administration of mifepristone and misoprostol [25]. Second, women who attempted to access care at very early gestations were required to wait, sometimes for multiple weeks, until their pregnancy was detectable on ultrasound. Recent evidence indicates that this requirement is also unnecessary and offers no improvement in efficacy or safety over proceeding without ultrasound confirmation of intrauterine pregnancy [26].

Looking to the future, our finding that some women would prefer to conduct their abortions at home is reflected by studies in a variety of settings indicating that women find self-administration of misoprostol and self-management at home highly acceptable [27][28][29]. Future service commissioning opportunities should include a critical appraisal of the role of telemedicine, which has demonstrated success in increasing access for women in other countries [30][31][32]. In Britain, at-home use of mifepristone and misoprostol would require regulatory policy changes to designate the home as an approved healthcare site in which abortion can take place, preferably accompanied by legislative changes to decriminalize abortion performed outside a registered healthcare facility. Decriminalization has been demonstrated in other settings including Victoria, Australia, to increase focus on abortion as an issue of health and empowerment rather than an issue of law [33]. Several reproductive health organizations in Britain have recently called for the criminal code to be reformed [34]. Ultimately, for commissioners to provide accessible and responsive services, they must be supported by updated policy and clinical frameworks informed by the best scientific evidence.

Implications.

The presence of multiple barriers to accessing abortion care in Great Britain highlights the need for future guidelines to recommend a more woman-centered approach to service provision. Reducing the number of clinic visits and designing services to meet the needs of those living in controlling circumstances are particularly important goals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Worrell and Maaike Schippefelt for excellent research assistance.

Funding

Support for this research was provided by the Society of Family Planning through a Career Development Award SFPRF10-JI2 (ARAA) and in part by infrastructure grants for population research from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health R24HD04284 (ARAA) and P2C HD047879 (JT). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Society of Family Planning or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests

ARAA reports no conflicts of interest. RG is the Founder and Director of Women on Web. KG and MS are members of the Women on Web helpdesk team. JT is a member of the Board of Directors of the Women on Web Foundation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1. [Accessed April 22nd 2017];The Abortion Act. 1967 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1967/87/section/1.

- 2.Mills S. Brief background to Irish abortion law. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017;124(8):1216. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britain’s Abortion Law: What it says and why. [Accessed April 22nd 2017];Bpas Reproductive Review. 2013 May; http://www.reproductivereview.org/images/uploads/Britains_abortion_law.pdf.

- 4.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Evidence-based Guideline Number 7. [Accessed April 22nd 2017];The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion. 2011 Nov; https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/abortion-guideline_web_1.pdf.

- 5. [Accessed April 22nd 2017];Offences Against the Person Act. 1861 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/24-25/100/contents.

- 6.Goldbeck-Wood S. Reforming abortion services in the UK: less hypocrisy, more acknowledgment of complexity. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 2017:3–4. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101696. Online Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomperts RJ, Jelinska K, Davies S, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Kleiverda G. Using telemedicine for termination of pregnancy with mifepristone and misoprostol in settings where there is no access to safe services. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2008;115(9):1171–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. 2. World Health Organization; 2012. [Accessed April 22nd 2017]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70914/1/9789241548434_eng.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [Accessed April 22nd 2017];Women on Web website. https://www.womenonweb.org/en/i-need-an-abortion.

- 10.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.British Pregnancy Advisory Service. [Accessed April 22nd 2017];Information on Abortion Prices. https://www.bpas.org/abortion-care/considering-abortion/prices/

- 12.UK Department of Health. [Accessed September 3rd 2017];Report on abortion statistics in England and Wales for 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/618533/Abortion_stats_2016_commentary_with_tables.pdf.

- 13.Information Services Division Scotland. [Accessed September 3rd 2017];Termination of Pregnancy Statistics Year ending. 2016 Dec; https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Sexual-Health/Publications/2017-05-30/2017-05-30-Terminations-2016-Report.pdf.

- 14.Care Quality Commission. [Accessed April 22nd 2017];Overview and CQC Inspection Ratings. 2016 Dec 20; http://www.cqc.org.uk/content/cqc-publishes-inspection-reports-marie-stopes-international.

- 15.UK Office for National Statistics. [Accessed September 3rd 2017];Internet access – households and individuals. 2017 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/2017.

- 16.Caird L, Cameron ST, Hough T, Mackay L, Glasier A. Initiatives to close the gap in inequalities in abortion provision in a remote and rural UK setting. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 2016;42(1):68–70. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heller R, Purcell C, Mackay L, Caird L, Cameron ST. Barriers to accessing termination of pregnancy in a remote and rural setting: a qualitative study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2016;123(10):1684–91. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baum SE, White K, Hopkins K, Potter JE, Grossman D. Women’s Experience Obtaining Abortion Care in Texas after Implementation of Restrictive Abortion Laws: A Qualitative Study. PloS one. 2016;11(10):e0165048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jerman J, Frohwirth L, Kavanaugh ML, Blades N. Barriers to Abortion Care and Their Consequences For Patients Traveling for Services: Qualitative Findings from Two States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2017;49(2):95–102. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doran FM, Hornibrook J. Barriers around access to abortion experienced by rural women in New South Wales, Australia. Rural and remote health. 2016;16(3538) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster AM, LaRoche KJ, El-Haddad J, DeGroot L, El-Mowafi IM. “If I ever did have a daughter, I wouldn’t raise her in New Brunswick:” exploring women’s experiences obtaining abortion care before and after policy reform. Contraception. 2017 Feb 21; doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.02.016. Online Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall M, Chappell LC, Parnell BL, Seed PT, Bewley S. Associations between intimate partner violence and termination of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(1):e1001581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bahk J, Yun SC, Kim YM, Khang YH. Impact of unintended pregnancy on maternal mental health: a causal analysis using follow up data of the Panel Study on Korean Children (PSKC) BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2015;15(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0505-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelman A, Rosenfeld EA, Nikolajski C, Freedman LR, Steinberg JR, Borrero S. Abortion Stigma Among Low-Income Women Obtaining Abortions in Western Pennsylvania: A Qualitative Assessment. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2017;49(1):29–36. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ngo TD, Park MH, Shakur H, Free C. Comparative effectiveness, safety and acceptability of medical abortion at home and in a clinic: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011 May;89(5):360–70. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.084046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bizjak I, Fiala C, Berggren L, Hognert H, Sääv I, Bring J, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Efficacy and Safety of Very Early Medical Termination of Pregnancy: a cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14904. Online Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lohr PA, Wade J, Riley L, Fitzgibbon A, Furedi A. Women’s opinions on the home management of early medical abortion in the UK. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 2010;36(1):21–5. doi: 10.1783/147118910790290894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kallner HK, Fiala C, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Assessment of significant factors affecting acceptability of home administration of misoprostol for medical abortion. Contraception. 2012;85(4):394–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purcell C, Cameron S, Lawton J, Glasier A, Harden J. Self-management of first trimester medical termination of pregnancy: a qualitative study of women’s experiences. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017 Apr 19; doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14690. Online Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raymond, Elizabeth G, Chong Erica, Hyland Paul. Increasing access to abortion with telemedicine. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176(5):585–586. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossman DA, Grindlay K, Buchacker T, Potter JE, Schmertmann CP. Changes in service delivery patterns after introduction of telemedicine provision of medical abortion in Iowa. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(1):73–78. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aiken ARA, Digol I, Trussell J, Gomperts R. Self-Reported Outcomes and Adverse Events Following Medical Abortion via Online Telemedicine: A Population-based Study in Ireland and Northern Ireland. BMJ. 2017;357:j2011. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wise J. Reform UK abortion law, say health organisations. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online) 2016 Dec 28;:355. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheldon S. Abortion law reform in Victoria: lessons for the UK. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 2017;43(1):25. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]