Abstract

Functional cardiac tissue engineering holds promise as a candidate therapy for myocardial infarction and heart failure. Generation of “strong-contracting and fast-conducting” cardiac tissue patches capable of electromechanical coupling with host myocardium could allow efficient improvement of heart function without increased arrhythmogenic risks. Towards that goal, we engineered highly functional 1cm × 1cm cardiac tissue patches made of neonatal rat ventricular cells which after 2 weeks of culture exhibited force of contraction of 18.0 ± 1.4 mN, conduction velocity (CV) of 32.3 ± 1.8 cm/s, and sustained chronic activation when paced at rates as high as 8.7 ± 0.8 Hz. Patches transduced with genetically-encoded calcium indicator (GCaMP6) were implanted onto adult rat ventricles and after 4–6 weeks assessed for action potential conduction and electrical integration by two-camera optical mapping of GCaMP6-reported Ca2+ transients in the patch and RH237-reported action potentials in the recipient heart. Of the 13 implanted patches, 11 (85%) engrafted, maintained structural integrity, and conducted action potentials with average CVs and Ca2+ transient durations comparable to those before implantation. Despite preserved graft electrical properties, no anterograde or retrograde conduction could be induced between the patch and host cardiomyocytes indicating lack of electrical integration. Electrical properties of the underlying myocardium were not changed by the engrafted patch. From immunostaining analyses, implanted patches were highly vascularized and expressed abundant electromechanical junctions, but remained separated from the epicardium by a non-myocyte layer. In summary, our studies demonstrate generation of highly functional cardiac tissue patches that can robustly engraft on the epicardial surface, vascularize, and maintain electrical function, but do not couple with host tissue. The lack of graft-host electrical integration is therefore a critical obstacle to development of efficient tissue engineering therapies for heart repair.

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease often results in myocardial infarction (MI), one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide [1]. Patients suffering from MI can progress to heart failure as the injured ventricles dilate and remodel. These patients are also at increased risk of fatal arrhythmias due to the presence of electrically inactive scar tissue [2, 3]. While current therapies for MI are based on interventional and surgical revascularization techniques to prevent further ischemic injury, the irrecoverable loss of functional myocardium typically leads to progressive pathological remodeling and loss of pumping function [4–7]. In terminal situations, mechanical assist devices and heart transplantation provide therapeutic options, however, available donor hearts are limited and these interventions are not without complications [8]. Consequently, significant effort is being devoted to developing methods for repair and/or regeneration of damaged myocardium to prevent or improve the physical and electrical sequela of MI.

Previous studies have described the implantation of engineered cardiac tissues in injured animal hearts, with notable results including partial preservation of ventricular function [9–13], reduction in fibrosis and scar size [10, 11], and improved vasculature in the infarct region [9, 10, 14, 15]. Expression of genetically encoded calcium sensors within stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (CM) prior to intramyocardial injection has indicated that these cells can survive long-term, exhibit functional calcium transients, and electrically couple with host tissue [16–19]. Interestingly, results in rodent models have reported suppression of arrhythmias after implantation of human CMs [16, 17], while CM implantation in non-human primate models resulted in significant induction of arrhythmias [18, 20]. Although it has been speculated that these conflicting observations can be attributed to the differences in animal sizes and heart rates [18], the ability to precisely monitor electrical activity at the host-graft interface is critical to understanding the mechanism of any observed anti- or pro-arrhythmic effects of cardiac cell therapy. Thus, in this study we developed an optical mapping technique to simultaneously visualize action potential propagation in both the implant and the recipient myocardium.

Mesoscopic hydrogel molding methods have been previously utilized for engineering of functional cardiac tissue network patches [21–24]. More recently, dynamic free-floating culture conditions were reported to enhance structural and functional properties of miniature and large engineered heart tissues termed “cardiobundles” [25, 26] and “cardiopatches” [27]. In the present study, we combined a simple hydrogel molding fabrication procedure and dynamic culture to produce 1×1 cm2 engineered cardiac tissue patches with high contractile forces and fast action potential propagation. These patches were implanted onto nude rat hearts, and 4–6 weeks later a dual-camera optical mapping system was used to simultaneously and distinctly record action potential propagation in the implanted patch and the recipient heart, thus enabling the precise evaluation of their electrical interactions and ability to undergo functional coupling. While no electrical integration was observed between the patch and the heart, the patch remained structurally intact, maintained electrical properties comparable to those before implantation, and did not alter electrophysiological function of the underlying myocardium. These results demonstrate generation of highly functional cardiac tissue patches capable of long-term preservation of structural and functional properties on the epicardial surface of the heart, and warrant future studies to improve functional coupling of graft and host cardiomyocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of neonatal rat ventricular cells

Cardiac cells were isolated from the ventricles of 2-day old neonatal rat hearts according to previously described methods [25, 28]. Animals were sacrificed using humane standards approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Duke University. Ventricles were harvested, minced, and enzymatically dissociated by serial digestion with trypsin and collagenase. Isolated cells were resuspended in DMEM/F-12 with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum and 10% Horse Serum, and pre-plated for 45 min at 37 °C to increase the fraction of cardiomyocytes in the cell suspension [28, 29]. To assess cardiomyocyte purity, pre-plated cells were fixed and permeabilized according to the manufacturer instructions (BD Biosciences # 554714), then stained with cardiac troponin T (cTnT) primary antibody (Abcam ab45932) and Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody. To assess fraction of endothelial cells, pre-plated cells were washed with PBS and stained with PE-conjugated CD31 antibody (BD Biosciences #555027) and APC-conjugated CD90 antibody (BD Biosciences #561409). Stained cells were analyzed in Beckman Astrios Sorter and BD FACSCanto A analyzer at the Duke Cancer Institute’s Flow Cytometry Shared Resource. Endothelial cells and fibroblasts were identified as CD31+ and CD90+ /CD31− [30] cells, respectively.

Patch fabrication and culture

Cellular preparations obtained from the neonatal rat hearts were utilized for fabrication of cardiac tissue patches by adapting previously described methods [22, 23, 31]. Reusable polydimethysiloxane (PDMS, Dow Corning) tissue molds were created by curing the polymer in a custom PTFE template. The tissue mold consisted of an 18mm × 18mm × 2mm volume with rectangular posts arranged near the outer boundary of the mold (Fig. 1A). After coating the tissue mold with 0.2% pluronic F-127 for 1 hour, a porous “frame” (inner dimensions 15 mm × 15 mm) laser-cut from spunbound nylon fabric (PBN-II, Cerex Advanced Fabrics) was inserted around the rectangular posts. The frame served to anchor the tissue patch during culture and facilitate functional measurements in vitro and implantation in vivo. A cell/hydrogel mixture was prepared with a final composition of 2 mg/mL fibrinogen, 1 U/mL thrombin, 10% matrigel, and 10 × 106 cells/mL [25]. To allow for tracking of cells and measurement of electrical propagation after implantation, a lentivirus was prepared to induce expression of a genetically-encoded calcium indicator under a myocyte-specific promoter (pRRL-MHCK7-GCaMP6 [32], full plasmid information available on AddGene). The lentivirus and polybrene (8 µg/mL) were mixed with the suspension of heart cells immediately prior to preparation of the hydrogel for patch fabrication. The cell/hydrogel mixture was pipetted into each tissue mold (600 µL per mold) and allowed to polymerize for 45 minutes at 37 °C. The tissue molds with polymerized cell/hydrogel mixture were then submerged in culture media consisting of low-glucose DMEM, 8% horse serum, 1% chick embryo extract, 1 mg/mL aminocaproic acid, 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, and 5 U/mL penicillin. Immediately after submerging the polymerized gel in culture media, the frame with patch was carefully removed from the tissue mold (Fig. 1B) and cultured in a 6 well plate under free-floating dynamic culture conditions, as previously described [25]. Media was initially changed 24 hours after patch fabrication and every 48 hours thereafter. Engineered patches were cultured for 12–14 days prior to functional assessment, immunohistology, or implantation.

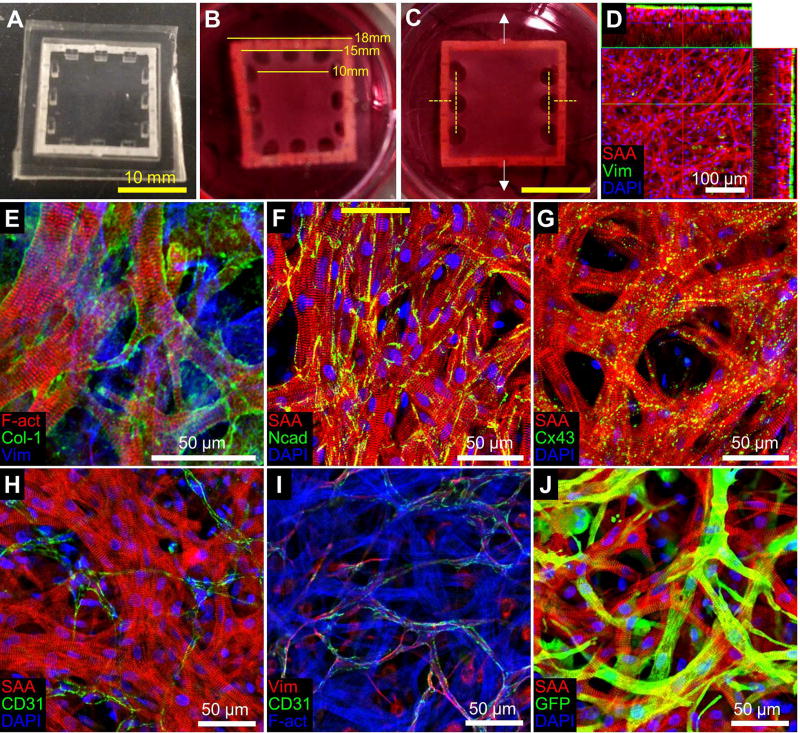

Figure 1. Structure of engineered cardiac tissue patch.

(A) PDMS mold and porous nylon frame used for fabrication of tissue patches. (B) Engineered rat cardiac patch after 12 days of culture, with dimensions shown for the outer part of the frame, the inner part of the frame, and the patch itself. (C) For isometric force testing patches only had side pores; yellow dashed lines represent locations where tissue and frame were cut allowing unidirectional force measurement in the direction of white arrows. (D) Engineered rat cardiac patch after two weeks of culture stained for sarcomereic α-actinin (SAA, red), vimentin (Vim, green), and DAPI (blue), with side projections derived from stack of confocal images. (E) Staining of cardiac patch for F-actin (F-act, red), Collagen 1 (Col-1, green), and Vim (blue). (F–H) Engineered rat cardiac patch stained for SAA (red), DAPI (blue), and either N-cadherin (Ncad, F), Connexin43 (Cx43, G) or CD31 (H) in green. (I) Staining of cardiac patch for Vim (red), CD31 (green), and F-act (blue). (J) Lentiviral transduction of GCaMP6 infects a significant fraction of cardiomyocytes in the patch. SAA (red), GFP (green), and DAPI (blue).

Patch histology

In vitro cultured tissue patches were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked as previously described [25]. Primary antibodies against sarcomeric alpha-actinin (Sigma A7811, 1:200 dilution), vimentin (Abcam ab92547, 1:500), collagen 1 (Abcam ab34710, 1:500), GFP (ThermoFisher A11122 / A11120, 1:500 / 1:100), CD31 (Abcam ab28364, 1:50), N-cadherin (Abcam ab12221, 1:500), and connexin-43 (Abcam ab11370, 1:200) were diluted in blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (ThermoFisher, 1:500 dilution) and nuclear stain (DAPI or Hoechst) were applied for 2 hours at room temperature, then samples were imaged with a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510).

Patch electrical and mechanical function

Action potential propagation in the cardiac patch was measured following 12–14 days of culture using a voltage-sensitive membrane dye, as previously described [22, 23, 33]. Patches were stained with 10 µM di-4 ANEPPS, incubated in 37 °C Tyrode’s solution with the excitation-contraction uncoupler blebbistatin (10 µM), and stimulated at the patch periphery by a platinum point electrode connected to a Grass SD9 stimulator. Optical signals were recorded by a photo diode array connected to 504 hexagonally arranged, 750 µm optical fibers. Data were acquired in 2–5 sec episodes after 10 sec of pre-pacing at a sampling rate of 1.2 kHz. Custom MATLAB software [34] was used to analyze the 504-channel recordings and derive propagation movies, activation maps, average conduction velocity (CV), action potential duration (APD), and maximum capture rate (MCR). To measure contractile force, engineered cardiac patches were fabricated fully attached along two opposite edges of the frame by removing half of the posts in the PDMS mold (Fig. 1C). Contractile forces were measured after 12–14 days of culture using a custom system consisting of a heated tissue bath (Cell MicroControls BD-42) maintained at 37 °C, a force transducer, and platinum field stimulus electrodes [21, 22, 31]. After mounting opposite edges of the patch frame to the force transducer and to a fixed PDMS block, the two unmounted sides of the frame were cut and detached from the patch (Fig. 1C). Patches were then stimulated at a rate of 1 Hz in Tyrode’s solution containing 1.8 mM Ca2+, and force data were acquired at a sampling rate of 1 kHz. The patches were stretched in increments of 3% up to 15% elongation using a 1-axis motorized stage (Thorlabs MT1-Z8), and active and passive force were measured at each tissue length.

Patch implantation on rat epicardium

Nude rats (Taconic Inc.) weighing approximately 150–200 grams were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and ventilated by endotracheal intubation. Following left thoracotomy, rats underwent ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery with 7-0 polypropylene suture. Two weeks after LAD ligation, echocardiography was performed to identify rats meeting the target inclusion criterion of fractional area shortening (FAS) less than 40% [9, 35]. However, surviving rats did not meet the inclusion criterion and instead exhibited only a mild decline in cardiac function (FAS = 48.1 ± 4.9% post-MI vs. 56.9 ± 6.6% pre-MI). The implantation study thus proceeded without exclusion to address the primary objective of quantifying patch survival, function, and ability to structurally and functionally integrate with recipient heart. A subset of patches was also implanted during the LAD ligation surgery (acute MI) or onto healthy hearts. For implantation, the patches were folded in half, attached cranially and caudally with two single 7-0 polypropylene sutures, and cut from the frame (Fig. 3A). Similar to previous studies [9, 11, 14, 36], patches remained implanted for 24 to 42 days, after which animals were sacrificed for functional and histological analysis. Following intraperitoneal injection of heparin (5 mg / kg body weight), rats were anesthetized as previously described, and the heart was excised and placed in ice-cold Tyrode’s solution. The aorta was rapidly cannulated with an 18-gauge feeding needle and affixed with suture thread. The heart was then attached to a Langendorff perfusion system with 37 °C oxygenated Tyrode’s solution, and flow rate was adjusted to maintain a perfusion pressure of 60–80 mmHg. Langendorff-perfused hearts were used for optical recordings of electrical activity as follows.

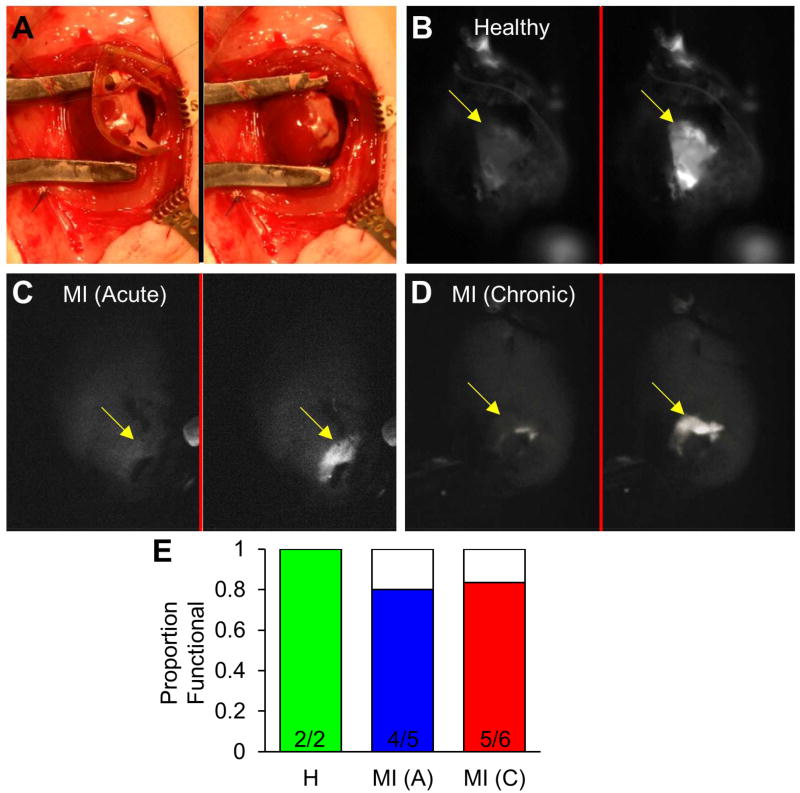

Figure 3. Survival and functionality of cardiac tissue patches following epicardial implantation in rats demonstrated by fluorescence recordings.

(A) Implantation of engineered cardiac tissue patch folded in half (left panel) and following removal of frame (right panel). (B–D) Snapshots of green fluorescence from Langendorff-perfused hearts 24–29 days after implantation of GCaMP6+ engineered cardiac patch in the setting of healthy heart (B), Acute MI (C), or Chronic MI (D); left panel shows patch at rest and right panel shows peak of Ca2+ transient during point stimulus-induced patch activation. (E) Proportion of implanted patches exhibiting Ca2+ transients in response to electrical stimulation. See also: Supplemental Video 3.

Ex vivo imaging of calcium transients in implanted patches

To initially assess whether implanted patches survived and exhibited calcium transients, the perfused hearts were imaged by an EMCCD camera with a 512 × 512 sensor (Andor iXon Ultra 897) and a 50mm f/0.95 TV lens (Navitar) at a sampling rate of 50 Hz. The heart was positioned with its anterior surface facing up towards the camera, located directly above the heart. The epicardial surface was illuminated by a 465–495 nm LED light source (SciMedia LEX2) and viewed through a 510–560 nm emission filter to image the patch-specific GCaMP6-reported calcium transients. If fluorescent flashing was not observed during normal sinus rhythm, then the implantation site was probed with a bipolar platinum point electrode by applying 1 Hz stimulation. Hearts which contained functional patches (exhibiting either spontaneous or stimulated GCaMP6 flashes) were then assessed by dual mapping of electrical propagation with high spatial and temporal resolution.

Dual optical mapping of action potential propagation in patch and heart

Hearts were labeled with voltage-sensitive dye RH237 (50 µM), by manually injecting 3 mL of dye solution at room temperature into the perfusion line at a rate of approximately 0.5 mL/sec. The perfusate was then changed to Tyrode’s solution with 10 µM blebbistatin to prevent motion artifacts. At the time of RH237 injection, the heart was maintained in a 50 mL conical tube for 5 minutes to prevent effluent dye from entering the imaging chamber and to improve epicardial staining. After staining, hearts were immersed in a cuboid acrylic chamber with one side wall made of thin glass to facilitate acquisition of fluorescent signals from the dual-camera system. During signal acquisition, the heart was lightly pressed against the coverslip wall to reduce curvature of the ventricle [37]. Perfused hearts were imaged with one objective lens (Leica) and two tube lenses (Leica) each directed to a separate CMOS camera (MiCAM Ultima, SciMedia, 100 × 100 recording sites), as depicted in Fig. 4A. The magnification was adjusted to obtain a 15mm × 15mm field of view (150 µm spatial resolution) by modulating the distance between the tube lenses and the camera sensors. Data from the two cameras were acquired simultaneously at a 1 kHz sampling rate. Fluorescent emissions of GCaMP6 and RH237 were separated by a dichroic mirror with 565 nm cutoff, a 510–560 nm band-pass emission filter for the GCaMP6 camera, and a >710 nm long-pass emission filter for the RH237 camera (Fig. 4A&B). To assess electrical coupling of the patch with the heart, data were acquired during normal sinus rhythm and during epicardial point pacing positioned several mm from the patch location. To measure conduction velocity (CV) of the patch and heart, data were acquired while applying point stimulus to the patch periphery. Generation of isochrones activation maps and CV calculation were performed using custom MATLAB software [38]. Heart CVs and APDs were also determined separately for the epicardial region under the patch (at recording sites also exhibiting GCaMP6 signals) and the region at least 1 mm away from the patch.

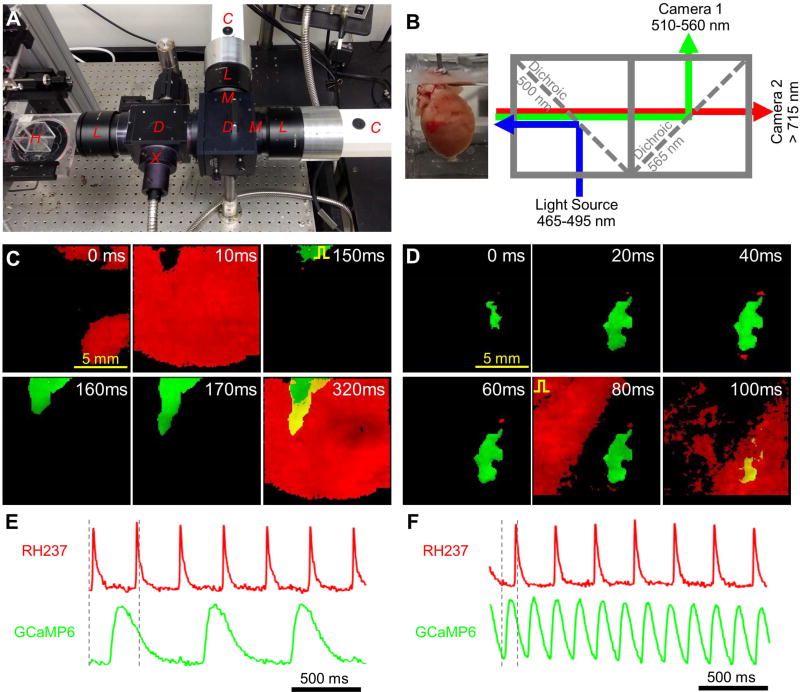

Figure 4. Simultaneous dual optical mapping of electrical signals from host heart and implanted engineered cardiac tissue patch.

(A) Photograph of dual-camera optical imaging system with labeled components: Cameras, Lenses, Dichroic mirrors, eXcitation filter, eMission filters, and Heart chamber. (B) Schematic of optical mapping system depicting fluorescent excitation of patch-specific calcium indicator (GCaMP6) and membrane voltage indicator (RH237) and separation of their emission spectra by dichroic mirrors and emission filters. (C) Movie snapshots demonstrating spontaneous activity of the heart (red) and simultaneous action potential propagation in the patch (green) electrically stimulated at a rate of 1.5 Hz (pulse sign indicates electrode location) (D) Movie snapshots demonstrating rapid spontaneous activity of engineered cardiac patch (green) and simultaneous action potential propagation in the heart (red) electrically stimulated at a rate of 3.5 Hz (pulse sign indicates electrode location). (E–F) Representative single-channel RH237 (red) and GCaMP6 (green) signals from (C) and (D), respectively; dashed vertical lines indicate period of time represented in panel C (0 – 320 ms) and panel D (0 – 100 ms).

See also: Supplemental Video 4.

Cardiac explant histology

After optical mapping on the Langendorff apparatus, hearts designated for H & E staining were cut into 6–8 transverse sections of approximately equal thickness, then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hr at 4 °C. Samples were embedded in paraffin and cut in 10 µm thick sections onto microscopy slides by the Research Histology Laboratory in the Department of Pathology at Duke University. After deparaffinization with Histo-Clear, samples were rehydrated with ethanol/water mixtures of gradually decreasing ethanol content, and stained with hematoxylin and Eosin Y. For immunostaining, live hearts were embedded in OCT compound, flash frozen on liquid nitrogen, sectioned on a cryotome (Leica CM3050, 10 µm thickness), fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, and immunostained as previously described for in vitro cultured engineered patches. Additional antibodies for explant sections included α myosin heavy chain (MYH, Santa Cruz sc-32732, 1:100 dilution) and von Willebrand factor (VWF, Abcam ab6994, 1:500). DAPI+ nuclei and VWF+ blood vessel branches were counted in the patch region (GFP+) and in the native myocardium (MYH+/GFP−).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. For comparisons of conduction velocity, calcium transient duration, action potential duration, nuclei density, and blood vessel density, a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine statistical significance with a significance level of α = 0.05.

RESULTS

In vitro properties of engineered cardiac tissue patches

The isolated heart cell population used for cardiac patch fabrication contained 82.4 ± 5.1% cardiomyocytes (Fig. S1A–B), 3.9 ± 0.6% CD31+ endothelial cells (Fig. S1C–D), 2.7 ± 0.8% CD90+/CD31− fibroblasts (Fig. S1C–D), and the remainder consisting of other stromal cells. After two weeks of dynamic culture, engineered cardiac patches had a thickness of approximately 100 µm, with cardiac fibroblasts mostly located on the top and bottom surfaces of the patch (Fig. 1D). They exhibited vigorous contractions yielding uniform bending of the supporting frame (Supplemental Video 1). Within the patch, collagen 1 was deposited in the extracellular spaces around cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1E), which, consistent with our previous reports [25, 31], displayed high density and elongated and cross-striated phenotype with abundant adherens junctions and gap junctions present at cell-cell contacts (Fig. 1F–G). Interestingly, endogenous endothelial cells that were present in the isolated cardiac cell population formed tube-like structures resembling microvascular networks (Fig. 1H–I). Lentiviral transduction during the patch preparation resulted in at least 50% of CMs expressing GCaMP6 (Fig. 1J), allowing tracking of patch survival and functionality after implantation.

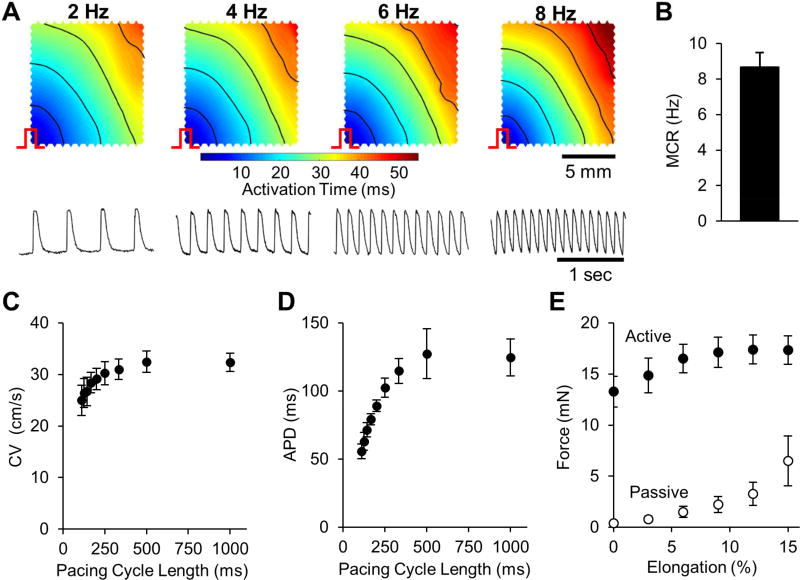

From optical mapping studies, the engineered cardiac tissue patches supported uniform propagation of action potentials in response to point stimuli (Fig. 2A, Supplemental Video 2) with an average maximum capture rate of 8.7 ± 0.8 Hz (Fig. 2B). At a basal pacing rate of 1 Hz, the patches exhibited an average conduction velocity (CV) of 32.3 ± 1.8 cm/s and an average APD of 124 ± 14 ms (Fig. 2C–D). As expected, patches demonstrated physiological CV and APD restitution curves, with APDs and CVs that decreased at increasing pacing rates. At optimal tissue elongation, the average isometric twitch force was 18.0 ± 1.4 mN, the highest reported in the field. Passive and active force-length curves showed expected trends with passive force exponentially increasing with tissue elongation and active force increasing until reaching maximum value at 12–15% elongation (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2. Electrical and mechanical function of engineered cardiac tissue patch in vitro.

(A) Representative isochronous maps of action potential propagation (top row) and optical traces of transmembrane voltage vs. time (bottom row) in a 2-week old engineered cardiac patch following point stimulus (pulse sign) at the bottom-left corner at 4 different pacing rates (2, 4, 6, and 8 Hz). (B) Maximum capture rate (MCR) measured as the highest rate at which each stimulus elicited an action potential. (C) Conduction velocity (CV) of action potentials vs. pacing cycle length (time between stimulus pulses). (D) Action potential duration (APD) at 80% repolarization vs. pacing cycle length. (E) Isometric active and passive force of engineered cardiac tissue patches at different levels of tissue elongation. n = 6 patches from 4 cell isolations for (B–E).

Survival of functional cardiac tissue patches 4–6 weeks after epicardial implantation

A total of 13 tissue patches were implanted onto adult rat hearts with chronic MI, acute MI, or no MI (healthy) for a period of 24 to 42 days. As noted in the Methods, surviving rats undergoing MI did not have a significant decline in ventricular function. Evidence of spontaneous patch activity (in the form of GCaMP6 flashing) was observed in 4 out of the 13 implanted patches, and an additional 7 patches displayed calcium transients in response to direct point stimulation (Fig. 3B–D, Supplemental Video 3). Overall, the presence of GCaMP6 signals confirmed that 11 out of 13 implanted patches (85%) survived and exhibited calcium transients (Fig. 3E), while we were unable to visualize 2 patches at the time of analysis (31 days post-implantation in chronic MI, 42 days post-implantation in acute MI).

Dual mapping of implanted tissue patch and heart to assess electrical integration

Simultaneous dual-wavelength fluorescent imaging was used to distinguish electrical propagation in the GCaMP6+ cardiac patch from electrical propagation of the underlying RH237-stained heart (Fig. 4A–B). For each of the 11 mapped patches, spontaneous activations in the heart did not result in GCaMP6 transients in the patch (Fig. 4C,E, Supplemental Video 4), indicating the absence of anterograde propagation from host to implanted cardiac tissue. In addition, spontaneous patch activations did not result in activations of the heart, indicating the absence of retrograde propagation. For example, occasional periods of rapid spontaneous beating in the patch did not accelerate the heart rate (Fig. 4D,F, Supplemental Video 4) or disturb its propagation pattern. Collectively, these results demonstrated that no graft-host electrical coupling of functional significance (i.e., able to support action potential propagation) occurred in the present study.

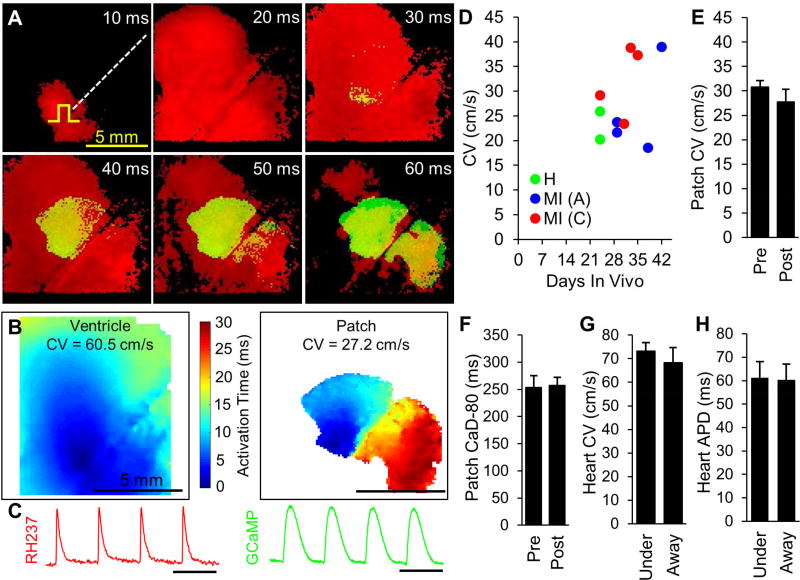

Electrical function of cardiac patches after implantation

In addition to evaluating survival and integration, we quantified the electrical function of the epicardially implanted patch by measuring its CV and Ca2+ transient duration during 2 Hz point stimulation (Fig. 5A–C, Supplemental Video 5). For the range of post-implantation periods in this study (24 – 42 days), there was no significant correlation between duration that patch spent on the epicardial surface in vivo and measured CV of the patch (Fig. 5D, r = 0.44, p = 0.198 for test of slope ≠ 0). Furthermore, the average CV of all mapped implanted patches (27.7 ± 2.6 cm/s) was not significantly different from the CV of same-batch patches tested at the time of implantation (30.8 ± 1.3 cm/s, Fig. 5E). Calcium transient duration (CaD) was also not significantly altered (Fig. 5F). The longitudinal CV of the native adult ventricle was 70.9 ± 6.2 cm/s, in agreement with previous reports [9, 39]. Furthermore, we found no difference in heart CV and APD under vs. away from the patch (Fig. 5G–H). Overall, measurements of patch CVs and CaDs from the GCaMP6 signals and host CVs and APDs from RH237 signals suggested that cardiac patches retain stable electrical phenotype several weeks after epicardial implantation, exert no local paracrine effects on the electrophysiology of underlying myocardium, and do not functionally couple with the host heart tissue.

Figure 5. Simultaneous assessment of propagation patterns and conduction velocities in the heart and patch.

(A) Snapshots of electrical propagation in engineered cardiac patch (green) and in the heart (red) following a 2 Hz point stimulus (pulse sign), 42 days after patch implantation. (B–C) Isochronous activation maps of the heart (left) and patch (right) (B) and representative optical signals from the heart (RH237, red) and the patch (GCaMP6, green) (C), derived from propagation movie represented in panel A. (D) Graph of patch CV vs. duration of implantation for patches in the setting of healthy heart (green), Acute MI (blue), or Chronic MI (red). (E–F) Average CV (E) and calcium transient duration at 80% repolarization (CaD-80, F) of patches designated for in vitro functional assessment pre-implantation (Pre, n = 9) and those explanted 24 – 42 days post-implantation (Post, n = 10). (G–H) CV (G) and action potential duration (APD, H) of the heart regions underneath the implanted patch (Under) vs. the regions at least 1 mm away from the patch (Away).

See also: Supplemental Video 5.

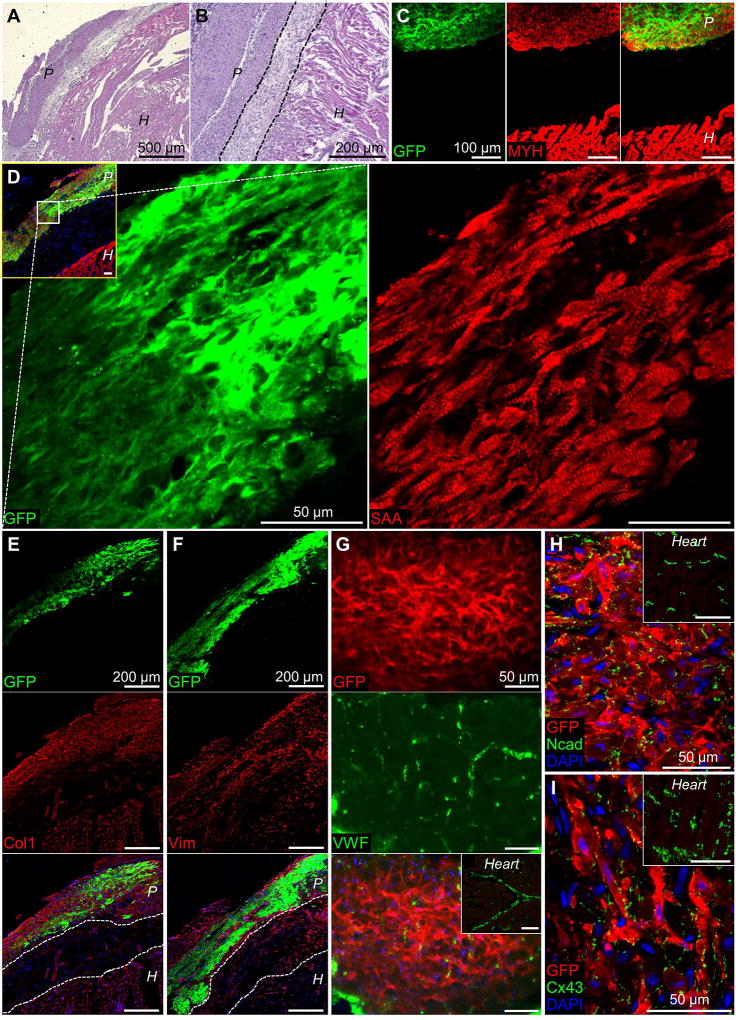

Histological assessment of cardiac patches after implantation

In hematoxylin and eosin staining of transverse heart sections, the patch was readily identified as being apposed to the epicardial surface (Fig. 6A). Cells in the patch were noticeably smaller compared to the larger cardiomyocytes of the heart and separated by a distinct cellular region with pale appearance (Fig. 6B). In the region identified as the implanted patch, immunofluorescent staining confirmed presence of GFP+ CMs (Fig. 6C), which displayed ubiquitously cross-striated structure (Fig. 6D). The implanted patches contained similar densities of cells (Fig. S2A) and vascular structures (Fig. S2B) relative to pre-implantation, which were higher and lower than in the host ventricle, respectively (Fig. S2). While the barrier region separating the patch from the heart did not contain more collagenous matrix compared to either the patch or heart (Fig. 6E), it contained a significant number of vimentin+ cells (Fig. 6F) and was devoid of CMs (Fig. 6C–D). Endothelial cells stained by VWF were found in the patch with evidence of capillary organization (Fig. 6G). Patch CMs were robustly connected with electrical and mechanical junctions (Fig. 6H–I), both of which were also readily observed pre-implantation (Fig. 1F–G). Thus, while the implanted patches maintained the structural and functional characteristics of in vitro engineered myocardium, the presence of insulating scar tissue between patch and heart prevented the graft-host functional integration.

Figure 6. Histological assessment of implanted cardiac tissue patches.

(A–B) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of transverse heart sections 33 days (A) or 24 days (B) after implantation of engineered cardiac patch. “P” and “H” denote patch and heart regions, respectively. (C) Representative immunofluorescence of transverse heart section with implanted patch stained for GFP (green) and myosin heavy chain (MYH, red, cardiomyocytes). (D) Higher magnification sections of implanted patch stained for GFP (green) and sarcomeric α-actinin (SAA, red); inset shows low-magnification merged image with DAPI (blue). Note cross-striated structure of the patch. (E–F) Implanted patch stained for GFP (top row) and collagen 1 (Col-1, E) or vimentin (Vim, F) in the middle row; bottom row shows merged images with DAPI (blue). (G) Representative section of implanted patch stained for GFP (top) with branched capillaries stained for von Willebrand factor (VWF, middle); bottom panel shows merged image with DAPI (blue); inset shows GFP/VWF staining of the host heart. (H–I) En face sections of implanted patch stained for GFP, Ncad (H) or Cx43 (I), and DAPI; insets show GFP/Ncad and GFP/Cx43 staining of the host heart.

DISCUSSION

In this study, methods for engineering highly functional cardiac tissues [22, 25] were scaled up to generate larger tissue patches suitable for rat epicardial implantation. The input cell number in our tissue patches (6 million) is approximately 20% of the population of adult rat ventricles (30 million [40, 41]), and thus comparable to the amount of cells lost in smaller infarcts (range of 23% – 50% [42, 43]). The implanted patches contain a primitive network of endothelial cells with a vessel density (252 ± 18 per mm2) falling within the range reported for engineered vascular tissues [15, 44–46] but significantly lower than that of native myocardium [47, 48]. The resulting contractile force of 18 mN and force per input cell of 3 nN/cell are significantly larger than previously described for neonatal rat engineered cardiac tissues (1.8 – 3.5 mN from 1 – 5 million input cells [9, 49–51]), likely due to reported advantages of auxotonic loading [9] and dynamic culture [25, 27]. With a final tissue cross-sectional area of ~ 1 mm2 (100 µm thick, 10 mm wide), the specific force of 18 mN/mm2 falls between the values reported for neonatal and adult rat myocardium (7.8–8.7 and 40–71 mN/mm2, respectively [52–55]). Additionally, the MCR of 8.7 Hz is faster than the resting heart rate of the adult rat (~6 Hz [56, 57]). Collectively, highly functional cardiac tissue patches developed in this study mimicked the contractile function of adolescent myocardium and were capable of sustaining uniform action potential propagation at physiological, adult rat heart rates.

In addition to the amplitude of force generation, the velocity of action potential conduction is another functional parameter that is critical for safe and effective patch therapy. The conduction velocity is a tissue-level, composite measure of myocardial function determined by CM size and orientation [58–60], expression of fast voltage-gated sodium channels [61–63], gap junctional coupling [64, 65], and density of extracellular space [66, 67]. Previous reports have assessed electrophysiological activity in the patch region using extracellular recording electrodes [9] or topical application of voltage-sensitive dyes [36, 68]. A more conclusive technique to assess electrical integration of implanted CMs has been described by Murry and coworkers [16–19] who compared GCaMP3-reported calcium transients in transplanted CMs with the ECG activity of host heart to derive evidence for synchronization and functional coupling. To enable detailed understanding of how grafted cells are activated relative to the activation of the underlying myocardium and to assess electric events at the graft-heart interface, we have utilized 2 high-speed CMOS cameras to map simultaneously, with high spatiotemporal resolution, the propagation of action potentials in both the implanted patch and the heart. This approach can allow important mechanistic studies of how implanted CMs can alter host electrophysiology and suppress or induce cardiac arrhythmias [16, 18, 20, 27, 69, 70].

By labeling implanted cardiomyocytes with a genetic calcium sensor, we demonstrate that the average conduction velocity of grafted isotropic patches was maintained in vivo at ~ 30 cm/s, consistent with the observed preservation of a dense but isotropic organization of CMs within the patch. The patch CV is thus intermediate between the maximal CVs of neonatal and adult rat ventricular myocardium (22–27 cm/s and 66–70 cm/s, respectively [9, 28, 39, 71]) and comparable with the transverse CV of the adult rat ventricular myocardium (32 cm/s [72]). While the maintenance of CV and CaD suggests that the patch remains healthy upon epicardial implantation, it also indicates a lack of further functional maturation. Interestingly, two recent studies have reported that mouse and human pluripotent stem cell-derived CMs (PSC-CMs) injected into neonatal or infarcted adult hearts undergo certain aspects of functional maturation, including increased cell size and faster calcium handling kinetics [73, 74]. The discrepancy could be due to several reasons including the absence of electrical integration in our study, while injection of CMs generally results in functional coupling with host cardiomyocytes [18, 20] (albeit with significantly decreased cell retention and survival compared to patch implantation [14]), or because we have measured tissue-level functional properties instead of single-cell properties. Furthermore, implanted PSC-CMs start at a more immature (and potentially plastic) state compared to neonatal rat CMs used in our study, which can allow detection of earlier maturation process even if full maturation to an adult phenotype is not supported. Interestingly, Kadota et al. reported complete maturation of neonatal rat CMs when injected into neonatal rat hearts for 3 months (9–10 weeks), whereas we have implanted engineered tissues in adult hearts for 3–6 weeks. The initial maturation state of implanted CMs, developmental stage of host heart, duration of implantation, and method of implantation (cell injection vs. 3D patch) may all affect the in vivo functional maturation of grafted CMs and warrant future studies to optimize cell therapies for post-infarction disease.

In this study, we found no evidence for electrical integration between any of the eleven grafted cardiac patches and host hearts that were either healthy or with modest degrees of infarct-induced injury. The degree of blood vessel integration between patch and heart in this study is unclear, although previous reports indicate that host vessel ingrowth and anastomosis are present after a similar period of time post-implantation [15, 27]. Simultaneously, we found no adverse paracrine effects of grafted cells on the electrical properties (CV and APD) of the underlying heart tissue. Histological analyses suggested that the lack of functional integration was caused by the formation of insulating scar barrier between patch and heart, which has been also observed in previous studies [11, 19, 68]. This barrier tissue was likely contributed by the thin layer of fibroblasts on the surface of the patch, host epicardial cells, and/or newly produced scar tissue. The existence of unexcitable and injury-activated epicardial cell layer [75], continuous motion of the contracting heart along with patch-heart interface, and the fact that cardiomyocytes are non-migratory cells, all represent serious obstacles to formation of stable cell-cell contacts necessary for robust gap junctional coupling between patch and heart. While two recent studies suggested a possibility that engrafted engineered tissues can functionally couple with host myocardium [68, 76], the rigorous dual-camera optical mapping assessment used in the current study could provide more conclusive evidence. Regardless, future advances to remove insulating patch-heart barrier or make it permissive to action potential conduction will be needed to enable direct functional benefits of cardiac patch therapy to infarcted hearts, beyond mere paracrine effects [77–79]. Conceivably, active modulation of the factors driving epicardial fibrosis after injury, including SDF-1 [80] or CCAAT enhancer-binding proteins [81], could reduce the amount of barrier tissue, while genetic engineering to render the barrier tissue electrically excitable [82] could enable patch-heart synchronization.

In summary, we developed highly functional cardiac tissue patches that retain structural organization and electrical properties for at least 6 weeks after epicardial implantation. We also describe a novel and versatile methodology to simultaneously track propagation of electrical signals in the patch and heart with high spatial and temporal resolution to allow more rigorous studies of their functional integration. Overall, these results are expected to aid ongoing efforts towards future use of engineered cardiac tissues for treatment of heart disease.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Video 1: Representative spontaneous contractions of a 2-week old cardiac tissue patch fabricated within a polymer frame. Attachment branches around a patch enable efficient removal from the frame during implantation.

Supplemental Video 2: Representative optically mapped action potential propagation in a 2-week cardiac tissue patch at progressively higher pacing rates. Patch (1cm × 1cm area) is paced by a point electrode from the bottom-left corner. Blue to red represent rest to peak of propagating action potential.

Supplemental Video 3: Survival and functionality of cardiac tissue patches following epicardial implantation in rats demonstrated by fluorescence recordings. Green fluorescence from surface of Langendorff-perfused rat hearts 24 days after implantation of GCaMP6+ engineered cardiac patch.

Supplemental Video 4: Simultaneous dual optical mapping of electrical signals from host heart and implanted engineered cardiac tissue patch. Transmembrane voltage of RH237-labeled heart (red) and intracellular calcium transients of GCaMP6+ engineered cardiac patch (green) recorded simultaneously during point pacing of the patch or the heart, 24–35 days after implantation.

Supplemental Video 5: Simultaneous assessment of propagation patterns in the heart and patch. Transmembrane voltage of RH237-labeled heart (red) and intracellular calcium transients of GCaMP6+ engineered cardiac patch (green) recorded during simultaneous pacing of the patch and heart together, 29–42 days after implantation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank H.D. Himel and J.J. Kim for technical assistance with the dual camera mapping system. This work has been supported by NIH grants HL104326, HL134764, and HL132389 and a grant from Foundation Leducq to N.B.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

References

- 1.Minino AM, et al. Deaths: final data for 2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;59(10):1–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henkel DM, et al. Ventricular arrhythmias after acute myocardial infarction: A 20-year community study. American Heart Journal. 2006;151(4):806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorenek B, et al. Cardiac arrhythmias in acute coronary syndromes: position paper from the joint EHRA, ACCA, and EAPCI task force. Europace. 2014;16(11):1655–1673. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolognese L, et al. Left ventricular remodeling after primary coronary angioplasty: patterns of left ventricular dilation and long-term prognostic implications. Circulation. 2002;106(18):2351–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000036014.90197.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savoye C, et al. Left ventricular remodeling after anterior wall acute myocardial infarction in modern clinical practice (from the REmodelage VEntriculaire [REVE] study group) Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(9):1144–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St John Sutton M, et al. Quantitative two-dimensional echocardiographic measurements are major predictors of adverse cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. The protective effects of captopril. Circulation. 1994;89(1):68–75. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeymer U, et al. Effects of a secondary prevention combination therapy with an aspirin, an ACE inhibitor and a statin on 1-year mortality of patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with a beta-blocker. Support for a polypill approach. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2011;27(8):1563–1570. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.590969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm MJ. Long-term outcome following heart transplantation: current perspective. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2015;7(3):549–551. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.01.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmermann W-H, et al. Engineered heart tissue grafts improve systolic and diastolic function in infarcted rat hearts. Nature Medicine. 2006;12(4):452–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawamura M, et al. Feasibility, safety, and therapeutic efficacy of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte sheets in a porcine ischemic cardiomyopathy model. Circulation. 2012;126(11 Suppl 1):S29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.084343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wendel JS, et al. Functional consequences of a tissue-engineered myocardial patch for cardiac repair in a rat infarct model. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20(7–8):1325–35. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riegler J, et al. Human Engineered Heart Muscles Engraft and Survive Long Term in a Rodent Myocardial Infarction Model. Circ Res. 2015;117(8):720–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iseoka H, et al. Pivotal Role of Non-cardiomyocytes in Electromechanical and Therapeutic Potential of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Engineered Cardiac Tissue. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2017 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekine H, et al. Cardiac Cell Sheet Transplantation Improves Damaged Heart Function via Superior Cell Survival in Comparison with Dissociated Cell Injection. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riemenschneider SB, et al. Inosculation and perfusion of pre-vascularized tissue patches containing aligned human microvessels after myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2016;97(Supplement C):51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiba Y, et al. Human ES-cell-derived cardiomyocytes electrically couple and suppress arrhythmias in injured hearts. Nature. 2012;489(7415):322–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiba Y, et al. Electrical Integration of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes in a Guinea Pig Chronic Infarct Model. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19(4):368–381. doi: 10.1177/1074248413520344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong JJ, et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate nonhuman primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510(7504):273–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerbin KA, et al. Enhanced Electrical Integration of Engineered Human Myocardium via Intramyocardial versus Epicardial Delivery in Infarcted Rat Hearts. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0131446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiba Y, et al. Allogeneic transplantation of iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerates primate hearts. Nature. 2016;538(7625):388–391. doi: 10.1038/nature19815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liau B, et al. Pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac tissue patch with advanced structure and function. Biomaterials. 2011;32(35):9180–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang D, et al. Tissue-engineered cardiac patch for advanced functional maturation of human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes. Biomaterials. 2013;34(23):5813–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bian W, et al. Robust T-tubulation and maturation of cardiomyocytes using tissue-engineered epicardial mimetics. Biomaterials. 2014;35(12):3819–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bian W, et al. Mesoscopic hydrogel molding to control the 3D geometry of bioartificial muscle tissues. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(10):1522–34. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackman CP, Carlson AL, Bursac N. Dynamic culture yields engineered myocardium with near-adult functional output. Biomaterials. 2016;111:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Asfour H, Bursac N. Age-dependent functional crosstalk between cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes in a 3D engineered cardiac tissue. Acta Biomater. 2017;55:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shadrin IY, et al. Cardiopatch platform enables maturation and scale-up of human pluripotent stem cell-derived engineered heart tissues. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1825. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01946-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bursac N, et al. Cardiac muscle tissue engineering: toward an in vitro model for electrophysiological studies. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(2 Pt 2):H433–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedrotty DM, et al. Cardiac fibroblast paracrine factors alter impulse conduction and ion channel expression of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83(4):688–97. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ieda M, et al. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate myocardial proliferation through beta1 integrin signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;16(2):233–44. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bian W, Jackman CP, Bursac N. Controlling the structural and functional anisotropy of engineered cardiac tissues. Biofabrication. 2014;6(2):024109. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/2/024109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madden L, et al. Bioengineered human myobundles mimic clinical responses of skeletal muscle to drugs. Elife. 2015;4:e04885. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkton RD, Bursac N. Engineering biosynthetic excitable tissues from unexcitable cells for electrophysiological and cell therapy studies. Nat Commun. 2011;2:300. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badie N, Bursac N. Novel micropatterned cardiac cell cultures with realistic ventricular microstructure. Biophys J. 2009;96(9):3873–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laflamme MA, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(9):1015–24. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furuta A, et al. Pulsatile cardiac tissue grafts using a novel three-dimensional cell sheet manipulation technique functionally integrates with the host heart, in vivo. Circ Res. 2006;98(5):705–12. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000209515.59115.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Efimov IR, et al. Optical mapping of repolarization and refractoriness from intact hearts. Circulation. 1994;90(3):1469. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Badie N, Satterwhite L, Bursac N. A method to replicate the microstructure of heart tissue in vitro using DTMRI-based cell micropatterning. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009;37(12):2510–21. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nygren A, et al. Voltage-sensitive dye mapping in Langendorff-perfused rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284(3):H892–902. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00648.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eschenhagen T. New tissue for failing hearts. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2013;15(1):1–2. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anversa P, et al. Myocyte cell loss and myocyte hypertrophy in the aging rat heart. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1986;8(6):1441–1448. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anversa P, et al. Myocardial infarction in rats. Infarct size, myocyte hypertrophy, and capillary growth. Circulation Research. 1986;58(1):26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller TD, et al. Infarct Size After Acute Myocardial Infarction Measured by Quantitative Tomographic 99mTc Sestamibi Imaging Predicts Subsequent Mortality. Circulation. 1995;92(3):334–341. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang CC, et al. Angiogenesis in a Microvascular Construct for Transplantation Depends on the Method of Chamber Circulation. Tissue Engineering. Part A. 2010;16(3):795–805. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghanaati S, et al. Rapid vascularization of starch–poly(caprolactone) in vivo by outgrowth endothelial cells in co-culture with primary osteoblasts. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2011;5(6):e136–e143. doi: 10.1002/term.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morin KT, Dries-Devlin JL, Tranquillo RT. Engineered microvessels with strong alignment and high lumen density via cell-induced fibrin gel compaction and interstitial flow. Tissue engineering. Part A. 2014;20(3–4):553–565. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rakusan K, et al. Morphometry of human coronary capillaries during normal growth and the effect of age in left ventricular pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation. 1992;86(1):38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hudlická O. Growth of capillaries in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Circulation Research. 1982;50(4):451. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kensah G, et al. A Novel Miniaturized Multimodal Bioreactor for Continuous In Situ Assessment of Bioartificial Cardiac Tissue During Stimulation and Maturation. Tissue Engineering Part C-Methods. 2011;17(4):463–473. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morgan KY, Black LD. Mimicking isovolumic contraction with combined electromechanical stimulation improves the development of engineered cardiac constructs. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2014:140111113629001. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimizu T, et al. Long-term survival and growth of pulsatile myocardial tissue grafts engineered by the layering of cardiomyocyte sheets. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(3):499–507. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moreno-Gonzalez A, et al. Cell therapy enhances function of remote non-infarcted myocardium. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2009;47(5):603–613. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasenfuss G, et al. Energetics of isometric force development in control and volume-overload human myocardium. Comparison with animal species. Circulation research. 1991;68(3):836–846. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.3.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solaro RJ, et al. Effects of acidosis on ventricular muscle from adult and neonatal rats. Circ Res. 1988;63(4):779–87. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.4.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raman S, Kelley M, Janssen P. Effect of muscle dimensions on trabecular contractile performance under physiological conditions. Pflügers Archiv. 2006;451(5):625–630. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bolter CP, Atkinson KJ. Maximum heart rate responses to exercise and isoproterenol in the trained rat. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 1988;254(5):R834. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.254.5.R834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu Y, Wu EX. MR study of postnatal development of myocardial structure and left ventricular function. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2009;30(1):47–53. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spach MS, et al. Electrophysiological effects of remodeling cardiac gap junctions and cell size: experimental and model studies of normal cardiac growth. Circ Res. 2000;86(3):302–11. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic Mechanisms of Cardiac Impulse Propagation and Associated Arrhythmias. Physiological Reviews. 2004;84(2):431–488. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang X, Pabon L, Murry CE. Engineering Adolescence: Maturation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Cardiomyocytes. Circulation Research. 2014;114(3):511–523. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Remme CA, Bezzina CR. REVIEW: Sodium Channel (Dys)Function and Cardiac Arrhythmias. Cardiovascular Therapeutics. 2010;28(5):287–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krause U, et al. Characterization of maturation of neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels SCN1A and SCN8A in rat myocardium. Molecular and Cellular Pediatrics. 2015;2:5. doi: 10.1186/s40348-015-0015-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harrell MD, et al. Large-scale analysis of ion channel gene expression in the mouse heart during perinatal development. Physiological Genomics. 2007;28(3):273–283. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00163.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaw RM, Rudy Y. Ionic Mechanisms of Propagation in Cardiac Tissue. Circulation Research. 1997;81(5):727. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Angst BD, et al. Dissociated Spatial Patterning of Gap Junctions and Cell Adhesion Junctions During Postnatal Differentiation of Ventricular Myocardium. Circulation Research. 1997;80(1):88–94. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Henriquez CS. Simulating the electrical behavior of cardiac tissue using the bidomain model. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 1993;21(1):1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fleischhauer J, Lehmann L, Kléber AG. Electrical Resistances of Interstitial and Microvascular Space as Determinants of the Extracellular Electrical Field and Velocity of Propagation in Ventricular Myocardium. Circulation. 1995;92(3):587. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weinberger F, et al. Cardiac repair in guinea pigs with human engineered heart tissue from induced pluripotent stem cells. Science Translational Medicine. 2016;8(363):363ra148. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roell W, et al. Engraftment of connexin 43-expressing cells prevents post-infarct arrhythmia. Nature. 2007;450(7171):819–824. doi: 10.1038/nature06321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gepstein L, et al. In Vivo Assessment of the Electrophysiological Integration and Arrhythmogenic Risk of Myocardial Cell Transplantation Strategies. STEM CELLS. 2010;28(12):2151–2161. doi: 10.1002/stem.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun LS, et al. Sympathetic innervation modulates ventricular impulse propagation and repolarization in the immature rat heart. Cardiovascular Research. 1993;27(3):459–463. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hardziyenka M, et al. Electrophysiologic Remodeling of the Left Ventricle in Pressure Overload-Induced Right Ventricular Failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;59(24):2193–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kadota S, et al. In Vivo Maturation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes in Neonatal and Adult Rat Hearts. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8(2):278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cho G-S, et al. Neonatal Transplantation Confers Maturation of PSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes Conducive to Modeling Cardiomyopathy. Cell Reports. 2017;18(2):571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou B, Pu WT. Epicardial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in injured heart. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(12):2781–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01450.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cingolani E, et al. Engineered Electrical Conduction Tract Restores Conduction in Complete Heart Block: From In Vitro to In Vivo Proof of Concept. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;64(24):2575–2585. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ogle BM, et al. Distilling complexity to advance cardiac tissue engineering. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(342):342ps13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jackman CP, et al. Human Cardiac Tissue Engineering: From Pluripotent Stem Cells to Heart Repair. Curr Opin Chem Eng. 2015;7:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yanamandala M, et al. Overcoming the Roadblocks to Cardiac Cell Therapy Using Tissue Engineering. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):766–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ruiz-Villalba A, et al. Interacting Resident Epicardium-Derived Fibroblasts and Recruited Bone Marrow Cells Form Myocardial Infarction Scar. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015;65(19):2057–2066. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huang GN, et al. C/EBP Transcription Factors Mediate Epicardial Activation During Heart Development and Injury. Science. 2012;338(6114):1599. doi: 10.1126/science.1229765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nguyen HX, Kirkton RD, Bursac N. Engineering prokaryotic channels for control of mammalian tissue excitability. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13132. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Video 1: Representative spontaneous contractions of a 2-week old cardiac tissue patch fabricated within a polymer frame. Attachment branches around a patch enable efficient removal from the frame during implantation.

Supplemental Video 2: Representative optically mapped action potential propagation in a 2-week cardiac tissue patch at progressively higher pacing rates. Patch (1cm × 1cm area) is paced by a point electrode from the bottom-left corner. Blue to red represent rest to peak of propagating action potential.

Supplemental Video 3: Survival and functionality of cardiac tissue patches following epicardial implantation in rats demonstrated by fluorescence recordings. Green fluorescence from surface of Langendorff-perfused rat hearts 24 days after implantation of GCaMP6+ engineered cardiac patch.

Supplemental Video 4: Simultaneous dual optical mapping of electrical signals from host heart and implanted engineered cardiac tissue patch. Transmembrane voltage of RH237-labeled heart (red) and intracellular calcium transients of GCaMP6+ engineered cardiac patch (green) recorded simultaneously during point pacing of the patch or the heart, 24–35 days after implantation.

Supplemental Video 5: Simultaneous assessment of propagation patterns in the heart and patch. Transmembrane voltage of RH237-labeled heart (red) and intracellular calcium transients of GCaMP6+ engineered cardiac patch (green) recorded during simultaneous pacing of the patch and heart together, 29–42 days after implantation.