Abstract

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are predominantly M2 phenotype in solid cancers including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Though differentiation of M2 macrophages has been recently linked to fatty acid oxidation (FAO), whether FAO plays a role in functional maintenance of M2 macrophages is still unclear. Here, we used an in vitro model to mimic TAM-HCC interaction in tumor microenvironment. We found that M2 monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) enhanced the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells through an FAO-dependent way. Further investigations identified that IL-1β mediated the pro-migratory effect of M2 MDM. Using etomoxir and siRNA to inhibit FAO and palmitate to enhance FAO, we showed that FAO was responsible for the up-regulated secretion of IL-1β and, thus, the pro-migratory effect in M2 MDMs. In addition, we proved that IL-1β induction was reactive oxygen species and NLRP3-dependent. Our study demonstrates that FAO plays a key role in functional human M2 macrophages by enhancing IL-1β secretion to promote HCC cell migration. These findings provide evidence for different dependency of energy sources in macrophages with distinct phenotypes and functions, and suggest a novel strategy to treat HCC by reprogramming cell metabolism or modulating tumor microenvironment.

Keywords: Tumor-associated macrophage, inflammation, metabolism, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, β-oxidation

1. Introduction

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have been proven to enhance tumor progression in various ways including promoting angiogenesis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Noy et al., 2014). These TAMs harboring tumor-promoting capacity are primarily alternatively-activated M2 phenotype, which—in contrast to M1 phenotype—was previously thought to be anti-inflammatory (Mantovani et al., 2002). However, recent investigations revealed a pro-inflammatory role of M2 macrophages in certain conditions such as arthritis and pancreatic cancer (Liu et all, 2013; Vogelpoel et al., 2014). In reality, macrophages are multi-functional and highly heterogeneous; their phenotypes change rapidly in response to distinct local tissue microenvironments (Gordon et al., 2014).

The shift of phenotypes in macrophages provokes significant changes of cellular metabolism. Macrophages with M1 phenotype dominantly use glycolysis (like “Warburg effect”) while M2 macrophages seem to prefer oxidative phosphorylation, particularly through enhanced fatty acid oxidation (FAO) (Kelly and O’Neill, 2015). It has been reported that FAO is essential for alternative activation of mouse macrophages (Huang et al., 2014; Vats et al., 2006). In contrast, FAO is dispensable for human macrophage M2 polarization (Namgaladze and Brune, 2014). However, whether FAO is required for the functional maintenance of M2 phenotype in macrophages is currently unknown.

TAMs play key roles in various types of solid tumor including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Shirabe et al., 2012), however, the mechanisms are still not fully understood. We previously identified a pro-inflammatory role of M2 macrophage in HCC with up-regulated interleukin (IL)-1β secretion, leading to enhanced EMT via hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α in HCC and pancreatic cancer cells (Zhang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2017). In conjunction, FAO promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation consequently leading to increased IL-1β secretion in both mouse and human macrophages (Moon et al., 2016). We, thus, asked whether FAO is involved in this event and whether FAO inhibition can reduce TAM-mediated tumor progression.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and reagents

HCC cell lines HepG2 and Hep3B were derived from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and were cultured in high glucose (4.5 g/L) Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Huh-7 cells were purchased from Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (JCRB) Cell Bank (Saito-Asagi, Ibaraki Osaka, Japan) and were cultured in low glucose (1.0 g/L) DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Human elutriated monocytes were derived from Blood Bank of National Institutes of Health (NIH) donated by healthy people. For macrophage differentiation, monocytes were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight and then cultured in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 30 ng/ml recombinant human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) for seven days. A half volume of medium was changed and fresh M-CSF was supplemented on the third day of differentiation. All culture medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For induction of M2 phenotype macrophages, cells were treated with 20 ng/ml human recombinant interleukin (IL)-4 (Peprotech) for 24 hours.

Etomoxir, bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES), 2-cyano-3-(1-phenyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-2-propenoic acid (UK5099), 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-HC), glybenclamide, mitoTEMPO, and sodium palmitate were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Loius, MO, USA). Bovine serum albumin (BSA)-conjugated palmitate was prepared using BSA and sodium palmitate according to the protocol (Seahorse Bioscience; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.2. Co-culture and migration/invasion assays

Co-culture of macrophages and HCC cells were performed using Transwell chambers with 8-µm pores on the membrane (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) in a 24-well plate. Macrophages and HCC cells were cultured in the lower and upper compartments of the Transwell chamber, respectively, for 48 hours. Macrophages were seeded at a density of 200,000 cells in 0.5 ml medium, and HCC cells were seeded at a density of 225,000 cells in 0.3 ml medium. For invasion assays, 30 µl Matrigel Matrix (1:5 dilution; Corning) was coated for 5 hours in the upper compartments. The non-invasive HCC cells in the upper chambers were removed by cotton swabs, and were stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution for 10 minutes. Migratory or invasive cells were counted under an optical microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), and results of five high power fields were averaged.

2.3. Cell proliferation assays

In brief, 500,000 M2 MDMs were cultured in a 12 well plate with or without etomoxir (100 µM) for 48 hours. Supernatants were collected, and floating cells and cell debris were removed by centrifugation (500 g, 10 min) at 4 °C. Then, 8,000 HCC cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and were cultured in normal or conditioned medium (1:1 diluted with fresh complete medium) for 48 hours. Cell proliferation was then detected using Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Techonlogies, Rockville, MD, USA) according to the manufacture’s instructions.

2.4. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen), and was reverse-transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA) using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR (Invitrogen). Totally 200 ng cDNA was used for qRT-PCR using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and specific primers. The following primers were used in this study: IL1B (forward: 5’-TCCAGGGACAGGATATGGAG-3’, reverse: 5’-TCTTTCAACACGCAGGACAG-3’), IL6 (forward: 5’-ATGAACTC CTTCTCCACAAGC-3’, reverse: 5’-GTTTTCTGCCAGTGCCTCTTTG-3’), IL10 (forward: 5’-AGAACCTGAAGACCCTCAGGC-3’, reverse: 5’-CCACGGCCTTGCTCTTGTT-3’), TNFA (forward: 5′-AGGCGCTCCCCAAGAAGACAGG-3’, reverse: 5’-CAGCAGGCAGAAGAGCGTGGTG-3′), VEGF (forward: 5’-GCCTTGCCTTGCTGCTCTAC-3’, reverse: 5’-TGATTCTGCCCTCCTCCTTCTG-3’), TGFB (forward: 5’-CCCAGCATCTGCAAAGCTC-3’, reverse: 5’-GTCAATGTACAGCTGCCGCA-3’), GAPDH (forward: 5′-AGGGCTGCTTTTAACTCGGT-3′, reverse: 5′-CCCCACTTGATTTTGGAGGGA-3’), mouse Il1b (forward: 5’-GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT-3’, reverse: 5’-ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT-3’), mouse Gapdh (forward: 5’-CAAAATGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTG-3’, reverse: 5’-TGATGTTAGTGGGGTCTCGCTC-3’).

2.5. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

For detection of IL-1β in the supernatants, 5 mM adenosine triphosphate (ATP; Sigma-Aldrich) was added 1 hour before supernatant collection. IL-1β concentration was then determined using human IL-1β/IL-1F2 Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacture’s instructions.

2.6. Metabolic analyses

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were assessed using Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer (Agilent Technologies). Totally 20,000 macrophages were seeded in each well for 9 to 12 wells. OCR and ECAR were detected using Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacture’s instructions. FAO-related OCR was performed and calculated using Seahorse XF Mito Fuel Flex Test Kit (Agilent Technologies). The results were normalized to cell number using cell protein concentration.

2.7. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) and plasmids transfection

Specific siRNA targeting IL1B, CPT1A, and NLRP3 and negative control (nc)-siRNA were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Transfection of macrophages was performed using P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector × Kit and 4D-Nucleofector Unit (Lonza; Walkersville, MD, USA) according to the manufacture’s instructions. In all experiments, siRNA was used at 100 nM, and plasmids were used at 3 µg per transfection.

2.8. Detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Macrophages were treated as indicated and stained with 4 µM MitoSOX Red Mitochondrial Superoxide Indicator (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 minutes at 37°C. After washing twice with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS)/Ca/Mg, fluorescence was detected using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon).

2.9. Lactate detection

Macrophages were cultured in 6-well plate and treated with IL-4 for 24 hours, followed by etomoxir treatment for another 36 hours. Supernatants were collected, and lactate concentration was determined using a Lactate Colorimetric Assay Kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA, USA). Samples were tested in duplicates, and totally three donors were included.

2.10. Lipid staining

Cellular lipid droplets were stained and quantified using Oil Red O Staining Kit (BioVision) according to the manufacture’s instructions.

2.11 Xenograft mouse model

The animal experiment was approved by the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee. Nude mice were randomized into two groups, and 1×106 Huh-7 cells were subcutaneously inoculated. After 10 days, etomoxir (20 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally injected every other day for a total of five times. An equal amount of phosphate buffer saline was injected as a negative control. Xenografts were harvested and homogenized for RNA extraction. The expression of mouse Il1b was detected using qRT-PCR.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD) or means ± standard error of the mean (SEM), as indicated. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For lactate analysis, paired Student’s t test was used. Other continuous variables were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test for comparison between two groups. For all statistical analyses, a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. FAO is required for macrophages to exert pro-tumoral effects in HCC cells

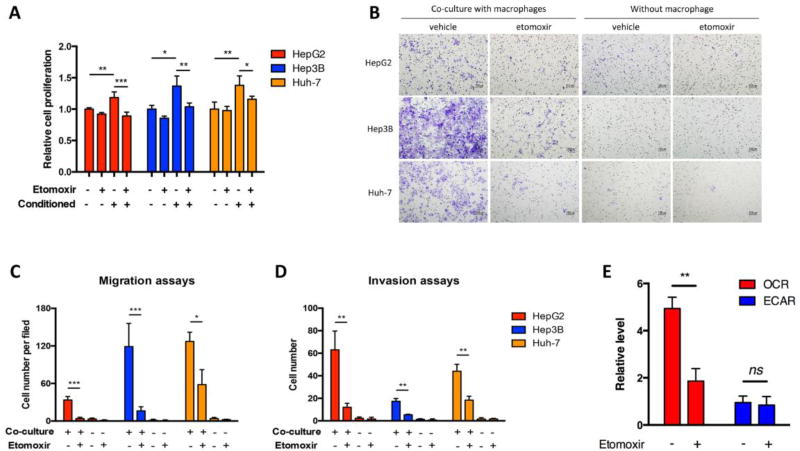

To confirm the roles of FAO in terms of TAMs-induced tumor progression, we first used an indirect co-culture method by using the conditioned media of M2-polarized human monocyte-derived macrophages (M2 MDMs) to culture HCC cells. In agreement with previous reports (Chen et al., 2012; Yeung et al., 2014), M2 MDM-conditioned medium significantly enhanced the proliferation of HCC cells (Figure 1A). Similarly, M2 MDMs also facilitated migration and invasion of HCC cells (Figure 1B–D). Of note, these pro-tumoral effects of M2 MDMs could be largely blocked by etomoxir (Figure 1A–D), an FAO inhibitor (Figure 1E). However, M0 MDMs had no effects in promoting cell proliferation and a much weaker potential of facilitating cell migration in regard to HCC cells, and these M0 MDM-induced effects had no responses to etomoxir treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Etomoxir attenuated M2 MDM-induced pro-tumoral effects. (A) M2 MDM-conditioned medium was collected after 48 hours of culture with or without etomoxir (100 µM). HepG2, Hep3B, and Huh-7 cells were cultured in normal medium or M2 MDM-conditioned medium for 48 hours, and cell proliferation was detected. (B and C) HCC cells and M2 MDMs were cultured in Transwell chambers with or without etomoxir (100 µM) for 24 hours. Migrated cells were stained with crystal violet and counted. (D) Invasion assays performed similar to migration assays in (B and C), but with Matrigel Matrix coated in the upper compartments of Transwell chambers. (E) M2 MDMs were treated with etomoxir (100 µM). Oxygen consumption rate and extracellular acidification rate were detected by Seahorse assays. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

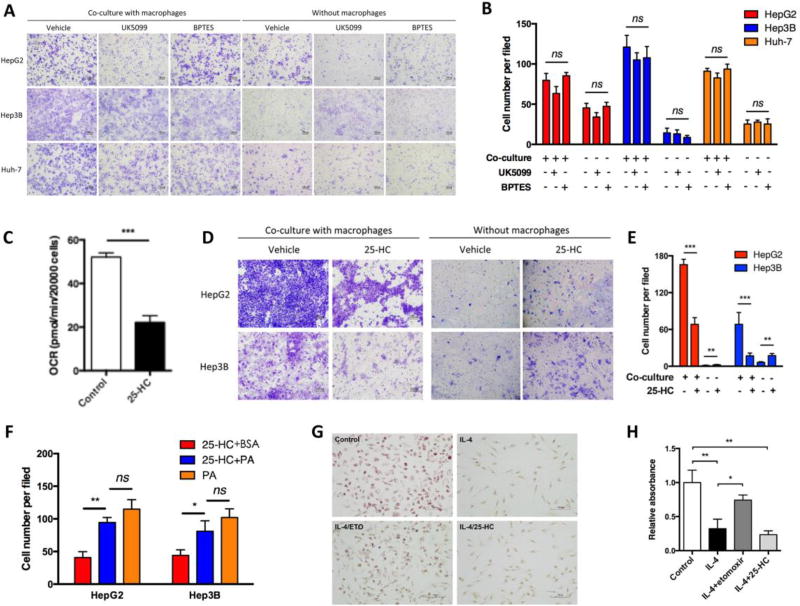

Given that M2 polarization is associated with increased mitochondrial respiration (Huang et al., 2014), we asked whether the pro-tumor effects of M2 MDMs in our settings were FAO-specific. The main sources of oxidative respiration for cells are glucose, glutamine, and fatty acid. We thus used BPTES and UK5099 to inhibit glutamine and glucose oxidation, respectively. Neither BPTES nor UK5099 was able show an anti-migratory effect in all three HCC cell lines (Figure 2A and B). Furthermore, we used 25-HC to inhibit fatty acid synthesis, which limited subsequent FAO in M2 MDMs by restraining fatty acid supply (Figure 2C). As expected, the M2 MDM-induced HCC migration was impaired with pretreatment of 25-HC (Figure 2D and E). Inversely, when palmitate was added in the presence of 25-HC to support FAO, the M2 MDM-induced HCC migration was restored to a great extent (Figure 2F). In support, IL-4 induced M2 polarization in the absence or presence of 25-HC decreased lipid droplets in MDMs while etomoxir partially restored them (Figure 2G and H). These results suggested that fatty acid metabolism, particularly FAO, was required for macrophage-induced HCC migration.

Fig. 2.

FAO played a specific role in M2 MDM-enhanced pro-migratory effect in HCC cells. (A and B) M2 MDMs were treated with UK5099 (50 µM) and BPTES (10 µM) for 41 hours to inhibit glutamine oxidation and glucose oxidation, respectively. Migration assays of HCC cells were performed using Transwell chambers and migrated cells were counted. (C) M2 MDMs were treated with 25-HC (5 µM) for 24 hours, and oxygen consumption rate was detected by Seahorse assays. (D and E) M2 MDMs were treated with 25-HC (5 µM) for 24 hours, and migration assays of HCC cells were performed and quantified. Migration of HCC cells without M2 MDMs co-culture was also tested. (F) M2 MDMs were cultured in medium supplemented with BSA-conjugated palmitate (200 µM) or BSA control, and Transwell assays of HCC cells were performed. (G and H) MDMs were treated as indicated (IL-4, 24 hours; etomoxir and 25-HC, 45 hours). Cellular lipid was stained and quantified using Oil Red O. Bar, 100 µm. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

3.2. FAO inhibition reduces IL-1β expression and secretion

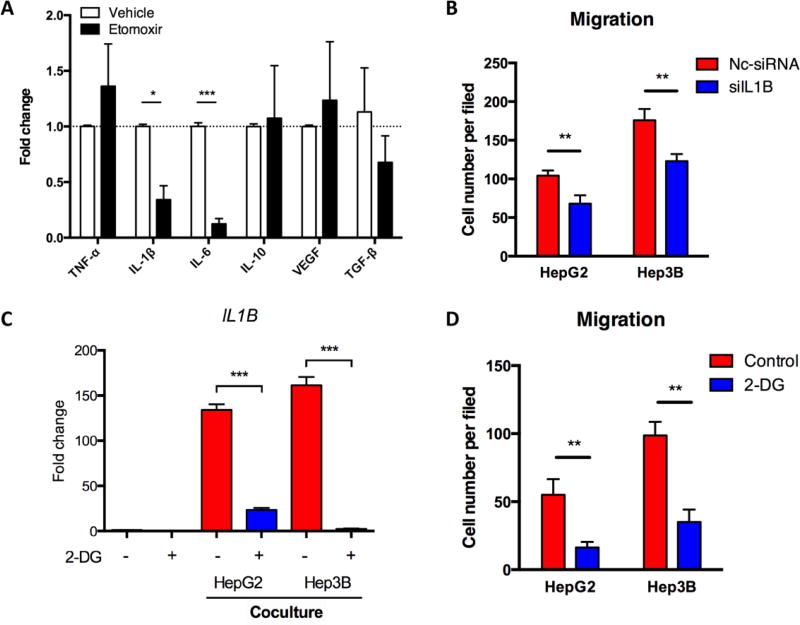

To explore the mechanism by which FAO mediates macrophage-enhanced migration in HCC cells, we tested the expression of several pro-invasive/migratory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transform growth factor (TGF)-β, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 in M2 MDMs co-cultured with HCC cells to seek the ones that could be inhibited by etomoxir. Among these cytokines, only IL-1β and IL-6 were significantly down-regulated in the presence of etomoxir (Figure 3A). IL-1β is a potent HIF-1α inducer even at a very low concentration in normoxia (Frede et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2017), and can induce EMT in many types of cancer including HCC (Li et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2017). A previous study also showed that etomoxir suppressed Il1b expression (Xu et al., 2015). Intriguingly, in M0 MDMs, etomoxir slightly increased rather than decreased IL1B transcription (data not shown). We thus hypothesized that IL-1β might be critical for etomoxir to affect M2 MDM-induced tumor migration. However, we only detected significant IL-1β secretion in MDMs after IL-4 treatment when co-cultured with HCC cells and non-significant IL-1β in HCC cell absence (data not shown). Although the exact reason is unknown, this result may be due to some HCC cell-derived stimulators such as IgG (Vogelpoel et al., 2014; Yi et al., 2015).

Fig. 3.

IL-1β mediated M2 MDM-enhanced pro-migratory effect in HCC cells. (A) M2 MDMs were treated with etomoxir (100 µM) for 24 hours and co-cultured with Hep3B cells. QRT-PCR was performed to identify the mRNA levels of indicated genes. (B) M2 MDMs were transfected with siIL1B (100 nM). MDMs-HCC cells co-culture and migration assays were performed. (C) M2 MDMs were treated with 2-DG (5 mM) and co-cultured with HCC cells for 24 hours. IL1B mRNA level was detected by qRT-PCR. (D) M2 MDMs were treated with 2-DG (5 mM) and co-cultured with HCC cells for 48 hours. Migration assays of HCC cells were performed. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

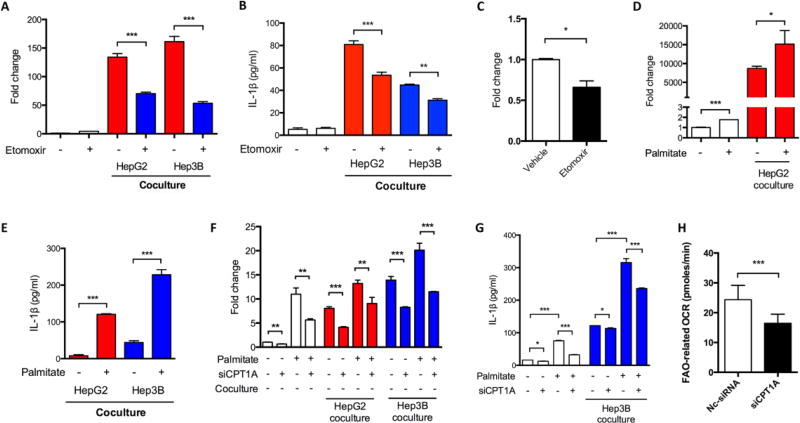

When we used IL1B siRNA to interfere IL-1β expression in M2 MDMs co-cultured with HCC cells, the pro-migratory effect of MDMs was inhibited (Figure 3B), indicating an IL-1β-mediated pro-migratory effect of macrophages. Intriguingly, the secretion of IL-1β is comparable in TAMs of both M1 and M2 phenotypes within tumor microenvironments (Chen et al., 2012). However, the mechanisms underlying IL-1β secretion in M1 and M2 TAMs are supposed to be different. It is well known that glycolysis contributes to IL-1β expression and secretion in M1 macrophages; yet, the mechanistic and metabolic involvements of IL-1β secretion in M2 macrophages are unclear and probably cannot be explained by glycolysis due to their FAO preference. Nevertheless, we found that 2-DG-mediated glycolysis inhibition in M2 MDMs significantly down-regulated IL1B transcription and MDM-induced HCC migration (Figure 3C and D), demonstrating that glycolysis was still critical in M2 macrophages. In addition, we found the mRNA and protein levels of IL1B were decreased by etomoxir in M2 MDMs co-cultured with HCC cells (Figure 4A and B). The etomoxir-induced inhibition of Il1b transcription was further confirmed in a xenograft mouse model (Figure 4C). In parallel, when palmitate was added to enhance FAO in M2 MDMs, IL-1β expression and secretion was further enhanced (Figure 4D and E). Furthermore, we found that palmitate-enhanced IL-1β expression could be partially blocked by knockdown of CPT1A using siRNA (Figure 4F and G), which encodes a protein critical for transporting fatty acids into mitochondria for FAO-mediated degradation. As expected, CPT1A knockdown reduced FAO of M2 MDMs (Figure 4H).

Fig. 4.

FAO mediated IL-1β secretion in M2 MDMs. (A and B) M2 MDMs were treated with etomoxir (100 µM) and co-cultured with HCC cells for 48 hours. IL1B mRNA level was detected by qRT-PCR. IL-1β concentration was determined by ELISA. (C) Nude mice subcutaneously inoculated with Huh-7 cells, etomoxir (20 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally administered. Mouse Il1b mRNA level in the xenografts was determined by qRT-PCR. (D) M2 MDMs were treated with palmitate (200 µM) and co-cultured with or without HepG2 cells for 48 hours. IL1B mRNA level was detected by qRT-PCR. (E) M2 MDMs were treated with palmitate (200 µM) and co-cultured with HCC cells for 48 hours. IL-1β secretion was detected by ELISA. (F and G) M2 MDMs were treated as indicated with palmitate (200 µM) and/or siCPT1A (100 nM). Co-culture with HCC cells sustained for 48 hours. IL1B mRNA level was detected by qRT-PCR. IL-1β secretion was detected by ELISA. (H) M2 MDMs were transfected with siCPT1A or negative control-siRNA (100 nM). FAO-related oxygen consumption rate was determined by Seahorse. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

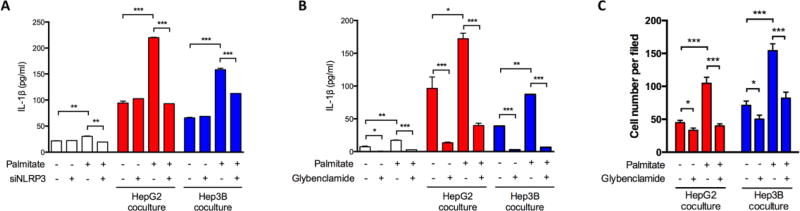

We then investigated whether FAO also affects the maturation of IL-1β, given that FAO can promote NLRP3 activation (Moon et al., 2016). We analyzed the secretion of IL-1β in MDMs co-cultured with HCC cells in response to the specific NLRP3 inflammasome activator ATP. Enhanced FAO by palmitate promoted IL-1β secretion, while NLRP3 siRNA transfection significantly impaired this effect of palmitate in MDMs (Figure 5A). Consistently, macrophages treated with glybenclamide, an inhibitor of NLRP3 inflammasome (Lamkanfi et al., 2009), showed a steady and remarkable decrease of IL-1β secretion regardless of palmitate addition (Figure 5B). A reduced pro-migratory effect of M2 MDMs was also observed in the presence of glybenclamide (Figure 5C). According to these findings, we inferred that FAO regulated MDM-induced HCC migration by promoting IL-1β expression and secretion.

Fig. 5.

NLRP3 was activated by FAO and mediated FAO-related IL-1β production. (A) M2 MDMs were transfected with siNLRP3 or negative control-siRNA (100 nM). Co-culture with HCC cells in the absence or presence of palmitate (200 µM) sustained for 48 hours. IL-1β secretion was detected by ELISA. (B and C) M2 MDMs were treated as palmitate (200 µM) and/or glybenclamide (200 µM), with or without co-culture of HCC cells for 48 hours. (B) IL-1β secretion was detected by ELISA. (C) HCC cell migration was assessed by Transwell assays. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

3.3. ROS is critical in FAO-associated IL-1β expression

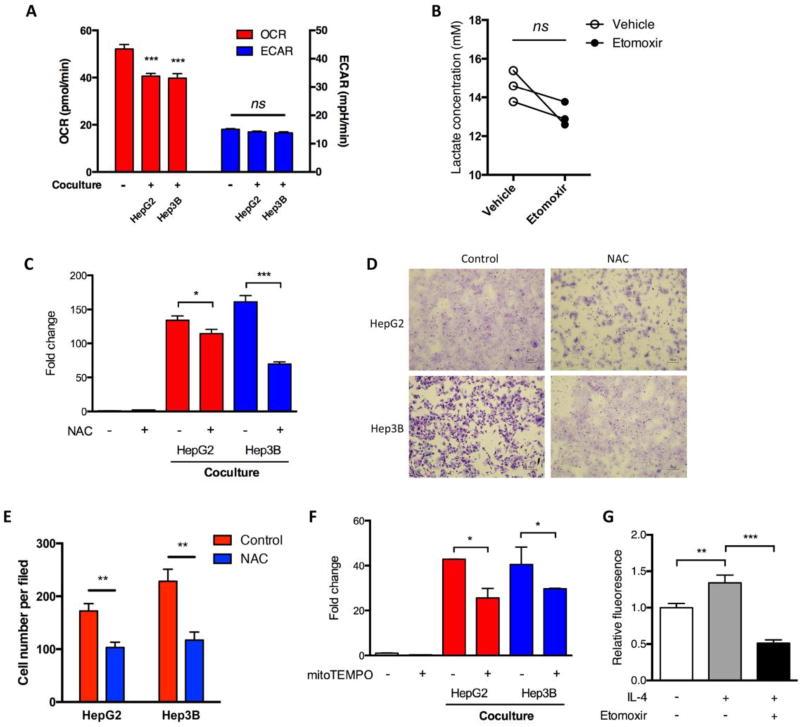

Although we showed that 2-DG inhibited HCC cell-induced IL1B transcription in MDMs, co-culture with HCC cells did not significantly enhance glycolysis of M2 MDMs in our settings (Figure 6A). Similarly, etomoxir failed to induce glycolysis as suggested by comparable levels of ECAR and released lactate in M2 MDMs with or without etomoxir treatment (Figures 1E and 6B). These findings suggested that glycolysis probably served as a basal and constitutional energy source and that an alternative way of IL-1β induction by FAO might exist.

Fig. 6.

ROS was important in FAO-related IL-1β production. (A) M2 MDMs were co-cultured with HCC cells for 24 hours. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were determined by Seahorse. (B) M2 MDMs from three donors were treated with etomoxir (100 µM) for 48 hours, and the lactate level in the supernatants was detected. (C) M2 MDMs were treated with NAC (10 mM) for 2 hours and co-cultured with HCC cells in the presence of NAC for another 24 hours. IL1B mRNA level was detected by qRT-PCR. (D and E) M2 MDMs were treated as in (C), and migration assays of HCC cells were performed. (F) M2 MDMs were pre-treated with mitoTEMPO (200 µM) for 2 hours and co-cultured with HCC cells in the presence of mitoTEMPO for another 24 hours. IL1B mRNA level was detected by qRT-PCR. (G) M2 MDMs were treated with or without etomoxir (100 µM). Mitochondrial ROS was determined using MitoSOX. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

We thus explored the mechanism by which IL-1β was induced by FAO. Since FAO produces more ROS than glycolysis (Rosca et al., 2012), and ROS can induce IL-1β expression in macrophages (Mills et al., 2016), we tested whether ROS mediated FAO-induced IL-1β in M2 MDMs. A decreased oxygen consumption rate of M2 MDMs in case of tumor cell co-culture suggested the metabolic repurposing of mitochondrial from ATP generation to ROS generation (Figure 6A), similar to the previous report (Mills et al., 2016). Similar to previous studies (Snodgrass et al., 2015), depletion of ROS by NAC decreased the mRNA level of IL1B in M2 MDMs (Figure 6C). NAC also weakened the pro-migratory effect of MDMs in both HepG2 and Hep3B cells (Figure 6D and E). Using mitoTEMPO, a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, we observed a similar pattern of alterations with NAC (Figure 6F). Because FAO is dependent on oxidative respiration in mitochondria, we further confirmed that inhibition of FAO by etomoxir led to decreased ROS (Figure 6G). Altogether, these results indicated that ROS mediated FAO-associated IL-1β expression in M2 macrophages.

4. Discussion

Different microenvironments influence many immune cells, including macrophages and T lymphocytes, to express distinct and even opposite functions; recent studies have linked this phenotypic shift in macrophages to metabolic change (Kelly and O’Neill, 2015). It is established that macrophages are dependent on glycolysis for classic activation; however, there is no consensus of metabolic dependency in alternatively activated macrophages. A few investigations reported that FAO plays key roles in macrophage alternative activation, but the conclusions were conflicting between human and murine results. Finkel’s group and Wolfgang’s group independently argued for the misleading conclusion that FAO plays a role in M2 polarization using bone marrow-derived macrophages by providing limited but convincing data acquired from a CPT2A conditional knockout mouse model (Gonzalez-Hurtado, et al., 2017; Nomura et al., 2016). While it seems convincing if two separate groups come to the same conclusion, this discrepancy may be explained by two reasons. On one hand, there may be an off-target effect of etomoxir or a FAO-irrelevant role of CPT1A because etomoxir did impair M2 polarization of macrophages in various ways (Huang et al., 2014; Vats et al., 2006). On the other hand, a subset of bone marrow-derived macrophages may have low expression of lysozyme M-encoding locus (Lyz2) (Vannella et al., 2014), which was used to introduce conditional CPT2A knockout in macrophages in the two above-mentioned studies. If the effect of FAO on M2 polarization of macrophage is highly flexible and redundant, it is likely that only extensive or even complete inhibition of FAO can compromise alternative activation of macrophages. Therefore, further data are needed to figure out whether FAO is necessary for alternative activation in human macrophages. Furthermore, the role of FAO in maintenance of the function of M2 macrophages is also unclear. Here, we reported that in M2 MDMs, FAO enhanced IL-1β secretion by a ROS and NLRP3-dependent manner and further facilitated MDM-induced malignant characteristics, especially migration of HCC cells. To show the effect of FAO we used different approaches including etomoxir, 25-HC, and siCPT1A to limit the FAO. However, these approaches still have some limitations. Etomoxir and siCTP1A may be argued by their FAO-irrelevant effects of CPT1A. 25-HC may affect tumor cell migration through other mechanisms. In fact, 25-HC slightly promoted tumor cell migration in the absence of macrophages as shown in our study, similar to the results observed in lung cancer (Chen et al., 2017). However, in the presence of macrophages, 25-HC reduced IL-1β production (Chen et al., 2017; Reboldi et al., 2014) and largely eliminated the IL-1β-enhanced migration of tumor cells. Taken these fingdings together, we believe FAO plays a role in macrophage-mediated enhancement of tumor cell migration.

In order to further investigate this pathway, we needed to delve into the novel field of immunometabolism since changes of macrophages were found closely related to cellular metabolism. For example, mitochondria within macrophages can be repurposed between ATP generation and ROS production according to an M2 or M1 inductor (Mills et al., 2016). The state of mitochondria—predominantly ATP or ROS production—also influences phenotypic shift of macrophages (Van den Bossche, et al., 2016). The slightly decreased OCR and potentially increased ROS in the presence of tumor cells in our study also suggested mitochondrial repurposing from ATP production to ROS generation. Despite these findings, the causal relationship between shifting of metabolism and gene expression is still unclear. We know that mitochondria-derived ROS seems to play key roles in macrophages in both M1 and M2 scenarios. On the other hand, ATP generated by oxidative phosphorylation or by glycolysis is not likely to be a defining factor of phenotype and function of macrophages. The predominance of glycolysis or oxidative phosphorylation in macrophages may be explained by the accompanied metabolites-related gene expression or cellular material synthesis. In our study, we used IL-4-induced M2 MDMs to mimic the M2 TAMs frequently found in tumor microenvironment. We showed that, similar to M1 macrophages, M2 MDMs also secreted IL-1β in the presence of cancer cells through FAO-associated ROS production, which could provoke IL1B transcription via up-regulation of Hif-1α (Mills et al., 2016). Proving that some M2 macrophage functions, such as HCC cell-induced pro-inflammatory and pro-migratory effects, relied on FAO, we found a new clue towards establishing the relation between macrophage FAO metabolism and function.

As versatile cells, macrophages present distinct functions and phenotypes depending on the local microenvironments in vivo (Ruffell et al., 2012). Our data confirmed that the functional change of macrophages could be achieved merely by modulating energy sources such as palmitate. Palmitate was found to promote inflammation in human macrophages (Snodgrass et al., 2015). However, we noticed that the effects of palmitate and etomoxir in human MDMs were highly case-dependent, though the exact reasons are under investigation. Currently, many studies have shown that HCC has altered fatty acid metabolism. For instance, HCC cells up-regulate de novo lipogenesis and down-regulate FAO (Li et al., 2015). Although this conclusion was still under debate because other investigators observed elevated FAO in HCC (Huang et al., 2013; Nath et al., 2015), our studies support this hypothesis by suggesting that the reprogrammed fatty acid metabolism of cancer cells may affect the function of TAMs by altering the amount of fatty acids in tumor microenvironment. Therefore, modulating energy sources in tumor microenvironment or targeting fatty acid metabolism in TAMs and cancer cells can be novel strategies in HCC treatment. In fact, some pioneer work has suggested the anti-tumoral efficacy of etomoxir in HCC, lung cancer, and breast cancer (Camarda et al., 2016; Li et al., 2013; Schlaepfer et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016). As far as we know, our study revealed for the first time that the M2 macrophage is another target of anti-FAO therapy in solid cancers.

Our final investigation looked towards the pro-inflammatory identities of macrophages as a result of modulation of cellular metabolism. An integral part of pro-inflammatory identities is the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β. This cytokine was traditionally believed to be mainly secreted by M1 macrophages. We, together with other groups, revealed that M2 macrophages show IL-1β secretion and pro-inflammatory effects with minimal to no change of M2 markers in several diseases such as cancer and arthritis (Vogelpoel et al., 2014). The mechanisms of pro-inflammatory effects in M2 macrophages are largely unknown. Currently, limited evidence argues that though M1 and M2 macrophages both have pro-inflammatory identities and suggests that the mechanisms differ between macrophage subtypes. As an example, glycolysis is involved in both M1 and M2 macrophage-related inflammation, but functions through different pathways. Glycolysis is predominant in and enhances pro-inflammatory effects of M1 macrophages (Galvan-Pena and O’Neill, 2014); whereas, similar with previous reports (Chiba et al., 2017), we demonstrate that glycolysis more likely plays a basal role in M2 MDMs. We also noticed that palmitate failed to enhance IL1B transcription in M1 MDMs induced by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ (data not shown). In addition, etomoxir was reported to suppress the expression of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, in M2 MDMs (Chiba et al., 2017). Thus, FAO seems to be more important in the pro-inflammatory effects of M2 macrophages, most likely in taking advantage of powerful mitochondrial respiration and avoiding frequent conversion between different energy supply modes in a rapidly changing microenvironment.

The interaction between tumor cells and macrophages seems important for the pro-inflammatory role of M2 macrophages since the presence of tumor cells significantly increased IL-1β production in M2 macrophages. While the exact mechanisms of this phenomenon are largely unknown, our recent studies revealed that tumor cell-derived IgG and O-glycoproteins promoted IL-1β production through FcγRI/III-Syk and TLR4-TRIF signaling pathways, respectively (data not shown). However, further investigations are needed.

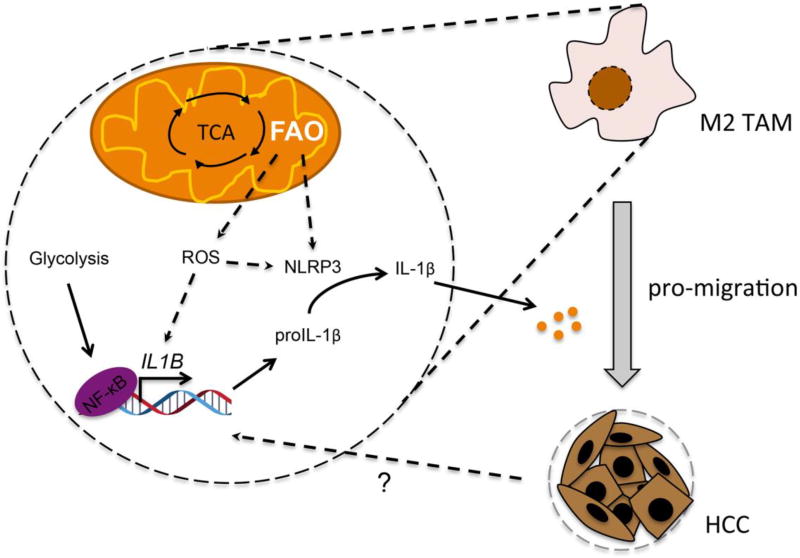

In conclusion, we demonstrate that FAO plays a critical role in M2 macrophage-enhanced tumor migration in a cancer cell co-cultural setting mimicking tumor microenvironment. M2 macrophage-secreted IL-1β can be regulated by modulation of FAO through an ROS and NLRP3-dependent manner (Figure 7). We demonstrate that certain functions of M2 macrophages, such as IL-1β secretion in tumor microenvironment, rely on FAO. Our study provides a novel perspective of immunometabolism in regulation of tumor migration.

Fig. 7.

A mechanistic scheme for the role of FAO in M2 macrophage-enhanced HCC migration. HCC-derived signaling induces IL-1β expression in M2 macrophage. FAO promotes IL-1β transcription and secretion by increasing ROS and by activating NLRP3, respectively. Secretion of IL-1β then enhanced migration of HCC cells.

Highlights.

-

●

Fatty acid oxidation rather than other energy sources supports M2 polarized macrophages-mediated enhancement of tumor cell migration.

-

●

M2 polarized macrophages can promote tumor cell migration by secreting IL-1β.

-

●

Fatty acid oxidation is essential for IL-1β secretion in M2 polarized macrophages.

-

●

Fatty acid oxidation increases reactive oxygen species and activates NLRP3 inflammasome.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Intramural Program of National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) at National Institutes of Health (NIH). We appreciate Mrs. Xiang Wang from NINDS for her technical support and critical discussion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interests: None.

References

- Camarda R, Zhou AY, Kohnz RA, Balakrishnan S, Mahieu C, Anderton B, Eyob H, Kajimura S, Tward A, Krings G, Nomura DK, Goga A. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation as a therapy for MYC-overexpressing triple-negative breast cancer. Nat. Med. 2016;22:427–432. doi: 10.1038/nm.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Zhang L, Xian G, Lv Y, Wang Y. 25-Hydroxycholesterol promotes migration and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;484:857–863. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Ma T, Shen XN, Xia XF, Xu GD, Bai XL, Liang TB. Macrophage-induced tumor angiogenesis is regulated by the TSC2-mTOR pathway. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1363–1372. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba S, Hisamatsu T, Suzuki H, Mori K, Kitazume MT, Shimamura K, Mizuno S, Nakamoto N, Matsuoka K, Naganuma M, Kanai T. Glycolysis regulates LPS-induced cytokine production in M2 polarized human macrophages. Immunol. Lett. 2017;183:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frede S, Freitag P, Otto T, Heilmaier C, Fandrey J. The proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 1beta and hypoxia cooperatively induce the expression of adrenomedullin in ovarian carcinoma cells through hypoxia inducible factor 1 activation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4690–4697. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan-Pena S, O'Neill LA. Metabolic reprograming in macrophage polarization. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:420. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Hurtado E, Lee J, Choi J, Selen Alpergin ES, Collins SL, Horton MR, Wolfgang MJ. Loss of macrophage fatty acid oxidation does not potentiate systemic metabolic dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;312:E381–E393. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00408.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S, Pluddemann A, Martinez Estrada F. Macrophage heterogeneity in tissues: phenotypic diversity and functions. Immunol. Rev. 2014;262:36–55. doi: 10.1111/imr.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SC, Everts B, Ivanova Y, O'Sullivan D, Nascimento M, Smith AM, Beatty W, Love-Gregory L, Lam WY, O'Neill CM, Yan C, Du H, Abumrad NA, Urban JF, Jr, Artyomov MN, Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Cell-intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:846–855. doi: 10.1038/ni.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Tan Y, Yin P, Ye G, Gao P, Lu X, Wang H, Xu G. Metabolic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma using nontargeted tissue metabolomics. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4992–5002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B, O'Neill LA. Metabolic reprogramming in macrophages and dendritic cells in innate immunity. Cell Res. 2015;25:771–784. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, Mueller JL, Vitari AC, Misaghi S, Fedorova A, Deshayes K, Lee WP, Hoffman HM, Dixit VM. Glyburide inhibits the Cryopyrin/Nalp3 inflammasome. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:61–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CW, Xia W, Huo L, Lim SO, Wu Y, Hsu JL, Chao CH, Yamaguchi H, Yang NK, Ding Q, Wang Y, Lai YJ, LaBaff AM, Wu TJ, Lin BR, Yang MH, Hortobagyi GN, Hung MC. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by TNF-alpha requires NF-kappaB-mediated transcriptional upregulation of Twist1. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1290–1300. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Huang Q, Long X, Zhang J, Huang X, Aa J, Yang H, Chen Z, Xing J. CD147 reprograms fatty acid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through Akt/mTOR/SREBP1c and P38/PPARalpha pathways. J. Hepatol. 2015;63:1378–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhao S, Zhou X, Zhang T, Zhao L, Miao P, Song S, Sun X, Liu J, Zhao X, Huang G. Inhibition of lipolysis by mercaptoacetate and etomoxir specifically sensitize drug-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cell to paclitaxel. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CY, Xu JY, Shi XY, Huang W, Ruan TY, Xie P, Ding JL. M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages promoted epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells, partially through TLR4/IL-10 signaling pathway. Lab. Invest. 2013;93:844–854. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. Inflammatory cytokines augments TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in A549 cells by up-regulating TbetaR-I. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:935–944. doi: 10.1002/cm.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–555. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills EL, Kelly B, Logan A, Costa AS, Varma M, Bryant CE, Tourlomousis P, Dabritz JH, Gottlieb E, Latorre I, Corr SC, McManus G, Ryan D, Jacobs HT, Szibor M, Xavier RJ, Braun T, Frezza C, Murphy MP, O'Neill LA. Succinate Dehydrogenase Supports Metabolic Repurposing of Mitochondria to Drive Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell. 2016;167:457–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon JS, Nakahira K, Chung KP, DeNicola GM, Koo MJ, Pabon MA, Rooney KT, Yoon JH, Ryter SW, Stout-Delgado H, Choi AM. NOX4-dependent fatty acid oxidation promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages. Nat. Med. 2016;22:1002–1012. doi: 10.1038/nm.4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Namgaladze D, Brune B. Fatty acid oxidation is dispensable for human macrophage IL-4-induced polarization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1841:1329–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath A, Li I, Roberts LR, Chan C. Elevated free fatty acid uptake via CD36 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14752. doi: 10.1038/srep14752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M, Liu J, Rovira II, Gonzalez-Hurtado E, Lee J, Wolfgang MJ, Finkel T. Fatty acid oxidation in macrophage polarization. Nat, Immunol. 2016;17:216–217. doi: 10.1038/ni.3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboldi A, Dang EV, McDonald JG, Liang G, Russell DW, Cyster JG. 25-Hydroxycholesterol suppresses interleukin-1-driven inflammation downstream of type I interferon. Science. 2014;345:679–684. doi: 10.1126/science.1254790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosca MG, Vazquez EJ, Chen Q, Kerner J, Kern TS, Hoppel CL. Oxidation of fatty acids is the source of increased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in kidney cortical tubules in early diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:2074–2083. doi: 10.2337/db11-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffell B, Affara NI, Coussens LM. Differential macrophage programming in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer IR, Rider L, Rodrigues LU, Gijon MA, Pac CT, Romero L, Cimic A, Sirintrapun SJ, Glode LM, Eckel RH, Cramer SD. Lipid catabolism via CPT1 as a therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2361–2371. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirabe K, Mano Y, Muto J, Matono R, Motomura T, Toshima T, Takeishi K, Uchiyama H, Yoshizumi T, Taketomi A, Morita M, Tsujitani S, Sakaguchi Y, Maehara Y. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg. Today. 2012;42:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00595-011-0058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass RG, Boß M, Zezina E, Weigert A, Dehne N, Fleming I, Brüne B, Namgaladze D. Hypoxia potentiates palmitate-induced pro-inflammatory activation of primary human macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2015;291:413–424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.686709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bossche J, Baardman J, Otto NA, van der Velden S, Neele AE, van den Berg SM, Luque-Martin R, Chen HJ, Boshuizen MC, Ahmed M, Hoeksema MA, de Vos AF, de Winther MP. Mitochondrial dysfunction prevents repolarization of inflammatory macrophages. Cell Rep. 2016;17:684–696. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannella KM, Barron L, Borthwick LA, Kindrachuk KN, Narasimhan PB, Hart KM, Thompson RW, White S, Cheever AW, Ramalingam TR, Wynn TA. Incomplete deletion of IL-4Ralpha by LysM(Cre) reveals distinct subsets of M2 macrophages controlling inflammation and fibrosis in chronic schistosomiasis. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004372. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vats D, Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, Zhang L, Smith KL, Morel CR, Wagner RA, Greaves DR, Murray PJ, Chawla A. Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1beta attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelpoel LT, Hansen IS, Rispens T, Muller FJ, van Capel TM, Turina MC, Vos JB, Baeten DL, Kapsenberg ML, de Jong EC, den Dunnen J. Fc gamma receptor-TLR cross-talk elicits pro-inflammatory cytokine production by human M2 macrophages. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5444. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MD, Wu H, Huang S, Zhang HL, Qin CJ, Zhao LH, Fu GB, Zhou X, Wang XM, Tang L, Wen W, Yang W, Tang SH, Cao D, Guo LN, Zeng M, Wu MC, Yan HX, Wang HY. HBx regulates fatty acid oxidation to promote hepatocellular carcinoma survival during metabolic stress. Oncotarget. 2016;7:6711–6726. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Chi F, Guo T, Punj V, Lee WNP, French SW, Tsukamato H. NOTCH reprograms mitochondrial metabolism for proinflammatory macrophage activation. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:1579–1590. doi: 10.1172/JCI76468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung OW, Lo CM, Ling CC, Qi X, Geng W, Li CX, Ng KT, Forbes SJ, Guan XY, Poon RT, Fan ST, Man K. Alternatively activated (M2) macrophages promote tumour growth and invasiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2015;62:607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi CH, Weng HL, Zhou FG, Fang M, Ji J, Cheng C, Wang H, Liebe R, Dooley S, Gao CF. Elevated core-fucosylated IgG is a new marker for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1011503. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1011503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JY, Zhang Q, Lou Y, Fu QH, Chen Q, Wei T, Yang JQ, Tang JL, Wang JX, Chen YW, Zhang XY, Zhang J, Bai XL, Liang TB. HIF-1α/IL-1β signaling enhances hepatoma epithelial-mesenchymal transition via macrophages in a hypoxic-inflammatory microenvironment. Hepatology. 2017 doi: 10.1002/hep.29681. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Bai XL, Chen W, Ma T, Hu QD, Liang C, Xie SZ, Chen CL, Hu LQ, Xu SG, Liang TB. Wnt/β-catenin signaling enhances hypoxia-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma via crosstalk with hif-1α signaling. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:962–973. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]