Abstract

A long-standing question in cellular neuroscience is how microtubules in the axon become organized with their plus ends out, a pattern starkly different from the mixed orientation of microtubules in vertebrate dendrites. Recent attention has focused on a mechanism called polarity sorting, in which microtubules of opposite orientation are spatially separated by molecular motor proteins. Here we discuss this mechanism, and conclude that microtubules are polarity sorted in the axon by cytoplasmic dynein, but that additional factors are also needed. In particular, computational modeling and experimental evidence suggest that static cross-linking proteins are required to appropriately restrict microtubule movements so that polarity sorting by cytoplasmic dynein can occur in a manner unimpeded by other motor proteins.

Keywords: microtubule, axon, microtubule polarity orientation, microtubule polarity sorting, microtubule sliding, cytoplasmic dynein

How do microtubules in the axon achieve their pattern of polarity orientation?

Neurons are terminally post-mitotic cells that use their microtubule arrays not for cell division, but as architectural elements for the elaboration of elongated axons and dendrites [1]. In addition to acting as compression-bearing struts that provide for the shape of the neuron, microtubules (see Glossary) also act as directional railways for organelle transport. Microtubules in the axon are nearly uniformly oriented, with the plus ends of the microtubules directed away from the cell body (“plus ends out”) [2, 3]. Preservation of this microtubule pattern, which directs organelle traffic by molecular motor proteins, is crucial for the normal functioning of the axon throughout the life of the neuron. This microtubule polarity pattern is also important for distinguishing features of the axon from the dendrite, as dendrites of vertebrate neurons have a mixed pattern of microtubule polarity orientation [4-7]. Long-standing questions in cellular neuroscience are how the plus-end-out polarity pattern of microtubules arises in the axon, how axons maintain this pattern during the life of the neuron, and how flaws are repaired in microtubule polarity orientation that may arise from plastic events or external insults (figure 1).

Figure 1. The axon's nearly uniform (plus-end-out) microtubule polarity pattern is at constant risk of being corrupted.

Schematic depicting the nearly uniform microtubule polarity pattern characteristic of the axon (left), and three ways that individual microtubules in the axon might undergo reversal of polarity orientation (right): microtubule severing, local nucleation, and microtubule looping/breaking. Such reversals need to be corrected to preserve the axon's plus-end-out polarity pattern. Microtubule severing, underlying plastic events such as axonal branch formation, can lead to microtubules short enough to flip orientation. Local microtubule nucleation via gamma-tubulin is normally restricted by augmin to the sides of pre-existing microtubules, thus ensuring that the new microtubule adopts the orientation of the pre-existing microtubule, but this could go awry if the augmin connection fails. Finally, microtubules at the growth cone can loop back on themselves, and if the looped microtubule breaks, the result will be a reverse-oriented microtubule.

A persistent but not uncontested idea in the literature has been that the polarity orientation of axonal microtubules is the direct result of the manner by which they are moved through the axon by molecular motor proteins [3, 8-11]. This movement of microtubules is generally referred to either as microtubule transport or microtubule sliding. In the axon, shorter microtubules are more readily transported than longer microtubules, with live-cell imaging revealing the rapid, robust and concerted transport of microtubules shorter than ten microns in length [11-14]. Some of these short microtubules elongate into long stationary microtubules, while others disassemble to yield subunits for the elongation of their neighbors [15]. Ongoing severing of long microtubules into shorter ones is crucial to ensure that the collective array of microtubules keeps moving down the axon. This is essential for axons to grow and also for the microtubule array to replenish itself throughout the life of the neuron [15]. Severing of microtubules may result in some microtubules being short enough (less than a micron in length) to flip orientation; such flipping is especially likely during plastic events such as axonal branch formation or during malfunctions of the cytoskeleton associated with disease or injury [16, 17]. Flipping is likely caused by the mix of available motor proteins imposing forces on very short microtubules, thus spinning them around in the axon. This would be especially likely in wider areas of the axon, such as lamellae. Local microtubule nucleation in the axon also introduces the possibility of reverse-oriented microtubules, specifically if the nucleation is not restricted to the sides of pre-existing microtubules, as it is when the system is functioning optimally [18]. Looping of microtubules at sites such as growth cones [19, 20] may also produce minus-end-out microtubules if the looped microtubule breaks.

How does the motor-driven transport of short microtubules impose order on the microtubule array of the axon and correct errors that might arise? One potential mechanism, called “polarity sorting,” is reflected in the behavior of microtubules and molecular motor proteins in vitro, in which a particular motor protein can spatially separate microtubules of opposite polarity orientation, thus creating uniformly oriented microtubule arrays. The fact that only short microtubules have been observed in rapid transit in the axon, however, suggests that the simplest kind of polarity-sorting mechanism may not be sufficient to explain how axons organize their microtubules.

Microtubule polarity sorting – lessons from the coverslip

In the early days of microtubule biology, the main idea for how cells organize their microtubules was via attachment of the minus end of the microtubules to an organizing structure such as the centrosome [21]. With growing awareness of myriad complex patterns of microtubule organization in specialized cell types such as neurons and polarized epithelial cells, this mechanism proved insufficient, especially given that microtubules often have their minus ends free in the cytoplasm, rather than attached to any recognizable organizing structure [22]. While cell biologists struggled with this conundrum, biophysicists were beginning to show that motor proteins could organize microtubules into asters, vortices and various three-dimensional arrays of higher order. The particular arrangement of microtubules depended on physical constraints (i.e., the shape of the space occupied by the microtubules), the particular motors, and the presence of other components such as chromatin beads or cross-linker proteins [23-28]. The idea of polarity sorting of microtubules in the axon is based on experiments in which microtubules of random orientation are applied to a lawn of a particular molecular motor protein adhered to a glass coverslip. A minus-end-directed motor moves the microtubules apart with their plus ends leading, while a plus-end-directed motor moves the microtubules apart with their minus ends leading (figure 2). Either way, the result is two populations of microtubules of uniform polarity orientation. In living cells, not all motor proteins are able to polarity sort microtubules, as a motor would have to interface via its cargo domain (or adaptor proteins) with a less moveable structure in order for its motor domain to be available to move a microtubule.

Figure 2. Dynein-mediated organization of microtubules on coverslips.

Dynein molecules anchored on coverslips by their cargo domain are capable of sorting microtubules by ‘walking’ towards the minus-end of microtubules and thereby driving microtubules of opposite orientation apart. Plus-end-out and minus-end-out orientations are relative to a hypothetical axon with cell body to the left, and growth cone or axon terminal to the right. Modified from Rao et. al. 2017 [29].

A motor-based polarity-sorting mechanism for axonal microtubules is appealing because it exploits the self-organizing properties of microtubules and motor molecules. Simply by exploiting these properties, the system works like a two-way conveyor belt that builds the microtubule array of the axon while ensuring that flaws do not accumulate. In the axon, plus-end-out microtubules would presumably move forward down the axon to populate its length, while minus-end-out microtubules would presumably move backward, in order to be cleared back to the cell body so that they do not accumulate and corrupt the microtubule polarity pattern of the axon [17, 29]. Consistent with this prediction of a polarity-sorting process occurring in the axon, live-cell imaging experiments on cultured vertebrate neurons have consistently revealed microtubules moving in both directions in the axon [11, 13, 29-31].

To generate and maintain a plus-end-out microtubule polarity pattern, a minus-end-directed motor would presumably be required. The minus-end-directed motor would carry out this function by interfacing with a less moveable structure than the mobile microtubule, such that it is the microtubule upon which the motor walks that moves, rather than the “cargo,” with the latter remaining stationary. However, living axons are not coverslips.

Axons contain an array of different motor proteins as well as a variety of non-motor microtubule-interacting proteins and structures. Recent studies suggest that various motors can influence microtubule organization in the axon, as can certain non-motor proteins that limit microtubule mobility. In light of these considerations, we posit that microtubule organization in the axon is established and preserved by a polarity-sorting mechanism with certain critical enhancements. The purpose of this article is to explore this idea, with emphasis on recent findings from our laboratory and others.

Cytoplasmic dynein as the chief microtubule transport motor in the axon

Cytoplasmic dynein, the best known minus-end-directed molecular motor protein, is a polarity-sorting motor in many cell types [32, 33]. Cytoplasmic dynein was first suggested to be the motor that transports microtubules anterogradely down the axon on the basis of the need for a motor that would transport microtubules with their plus ends leading [9, 34]. The idea was first given credence by experimental data on laboratory rodents indicating that most of the dynein that is transported anterogradely down the axon is transported in association with cytoskeletal proteins in the “slow component” of axonal transport [34], rather than in association with membranous vesicles in the “fast component.” Experimental data on cultured vertebrate neurons [9] and other cells [35] then showed that dynein is responsible for the outward transport of microtubules after their release from the centrosome. Visualizing microtubule transport in the axon of living neurons has been technically challenging [36], but a breakthrough in experimental design [13] enabled the movement of microtubules to be visualized in the axons of cultured rodent neurons using a photobleach approach (figure 3). These studies revealed that (i) most of the microtubule mass in the axon is stationary at any given time; (ii) only relatively short microtubules are in rapid concerted motion; and (iii) the short mobile microtubules move in both directions. When dynein heavy chain was partially depleted by RNA interference, substantially fewer anterograde movements of microtubules were observed [11]. However, in apparent contradiction to a dynein-based polarity-sorting mechanism, no decrease in the number of retrograde microtubule movements was observed. On this basis, a multi-motor model (rather than a simple polarity-sorting mechanism) was proposed, in which different motors move the microtubules in each direction in the axon [15].

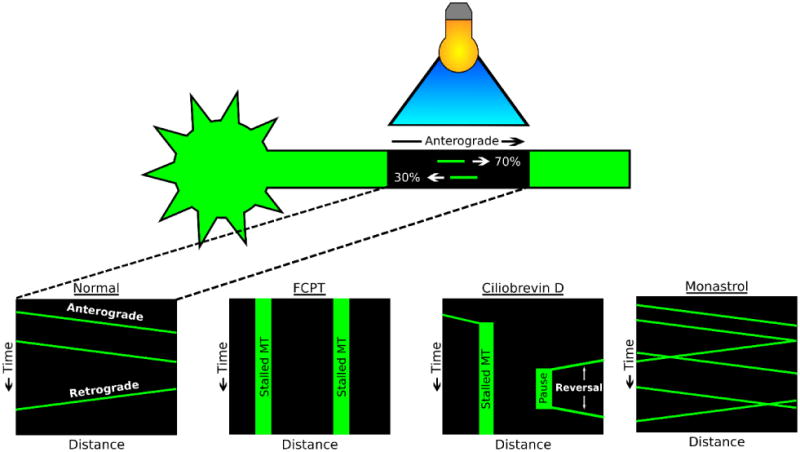

Figure 3. Contemporary technique for assaying microtubule transport in the axon.

Schematic depicting the photobleach-based technique for assaying microtubule transport in the axon of cultured neurons, with schematic kymographs (plots of distance versus time). Bottom panels: normal conditions, as well as neurons treated with drugs that result in a kinesin-5 rigor complex, dynein inhibition, or kinesin-5 inhibition (FCPT, Monastrol, or Ciliobrevin D, respectively). Note: In the first study to visualize axonal microtubule transport using this method, rhodamine-tagged tubulin was microinjected into cultured neurons [13]. In subsequent studies, GFP-tubulin was expressed in neurons [12, 30, 43]. In the most recent studies, tdEos-tubulin was expressed rather than GFP-tubulin [10, 29, 50-52]. tdEos fluoresces in the green channel, but after exposure to 405 nm laser light, the tdEos fluorophore switches to red channel fluorescence [65]. This “photoconversion” affords the opportunity for visualization of microtubule movements through the “photoconverted” zone in the green channel, and out of the zone in the red channel. Intermingling of red and green signal can also be monitored as a readout of sliding of longer microtubules, for example in migratory neurons [10].

In search of other motor proteins that are known to be able to regulate microtubule transport, our laboratory investigated as possibilities kinesin-5 (kif11), kinesin-6 (kif23) and kinesin-12 (kif15), all of which regulate the transport (i.e. “sliding”) of microtubules in the mitotic spindle. All three were found to be expressed in vertebrate neurons, but depletion of none of them reduced microtubule transport in either direction. In fact, in all three cases, microtubule transport frequency was elevated, and in both directions, when the motor was depleted or inhibited, and microtubule transport frequency was reduced when kinesin-5 was experimentally put into a rigor state [12, 14, 37] (figure 3). We concluded that these three motors, each functioning in its own way, act as energy-burning brakes to attenuate the number of microtubules that are in motion in the axon. Kinesins 5 and 12 act in the axon itself, while kinesin-6 acts at the level of the cell body to restrict movement of microtubules into the axon.

Is cytoplasmic dynein the polarity-sorting motor for axonal microtubules?

Two potential explanations for the RNA interference data may still support a dynein-based polarity-sorting model. The first is that the depletion of dynein by this method is incomplete [11], and the small amount of residual dynein may be sufficient to fuel a great deal of microtubule transport. Related to this first explanation is the possibility that a kinesin-14 family member might share some of the polarity-sorting duties with cytoplasmic dynein [15]. The second explanation, perhaps more likely, is that other motors that normally do not transport microtubules in the axon become capable of doing so, as dynein is gradually depleted by this method [17, 38, 39]. If the latter explanation is correct, microtubule polarity flaws (minus-end-out microtubules) would be expected to accumulate in the axon as dynein is gradually depleted, due to the ‘wrong’ motors transporting microtubules. In addition, acute dynein inhibition would be expected to prevent microtubule transport in both directions. In a recent report, we found both of these predictions to hold true [29]. When we applied Ciliobrevin D, a potent and specific inhibitor of cytoplasmic dynein [40], to cultures of rat sympathetic neurons just prior to imaging microtubule transport, we observed marked reductions of microtubule movements in both directions in the axon. We were able to capture images of mobile microtubules abruptly stopping in response to the drug. In cultures exposed to the drug for prolonged periods of time, minus-end-out microtubules began to accumulate, and the same was true of neurons in which dynein had been depleted or inhibited by other methods. These observations are consistent with work on both Drosophila and vertebrate axons, in which microtubule polarity flaws have been observed in axons with disrupted dynein-related proteins, including Lis1, dynactin, and Ndel1 [38, 39, 41].

In living cells, there is no glass coverslip against which microtubules can be transported by molecular motor proteins. Instead, the motors most likely interface with long stationary microtubules that act as substrates against which the short microtubules move, or the motor could interface with the actin cytoskeleton to provide such a substrate. In the case of dynein, there is precedent for both in the mitotic spindle, with astral microtubules sliding via dynein against the actin-based cell cortex and overlapping spindle microtubules sliding against one another [33, 42]. Experimental data on neurons indicates that both of these substrates are also used in the axon to transport short microtubules [43]. In the case of the actin cytoskeleton, it remains unclear whether dynein or dynein-related proteins interact directly with actin or with other structures associated with the actin filaments, but we suspect that the mechanism is analogous to how dynein slides astral microtubules during mitosis.

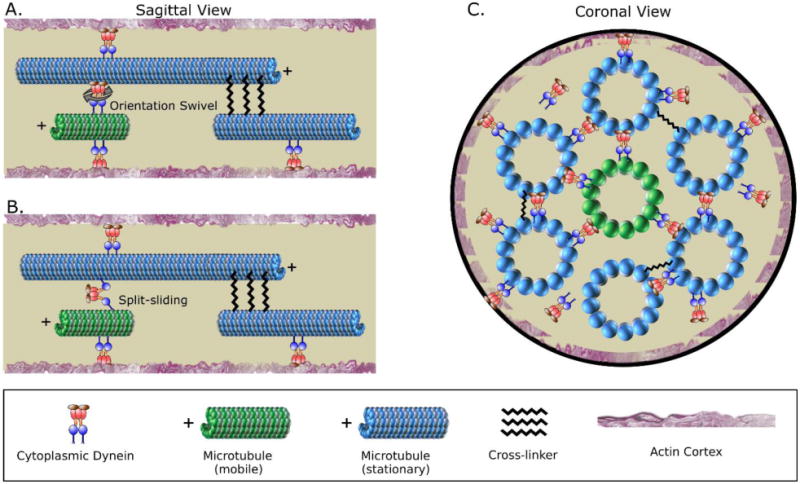

Questions arise about the logistics of a dynein-based polarity-sorting mechanism. For example, does it make sense that the same long microtubule could act equally well as a substrate for the transport of a minus-end-out short microtubule or a plus-end-out microtubule, both using dynein as the motor? The answer to this question lies within the known ability of dynein to swivel [42] (figure 4A). As long as dynein can swivel, the orientation of dynein's binding to the long microtubule is irrelevant, just as it is with regard to the binding of dynein to a glass coverslip or the actin cytoskeleton. Another possibility that would polarity sort the microtubules in a different way is a phenomenon called “split-sliding,” in which the two motor domains of a dynein complex each interacts with a different microtubule, in which case the polarity orientation of both microtubules would be relevant [42]. In this scenario (figure 4B), no motion of commonly oriented microtubules would be generated, but oppositely orientated microtubules would be driven apart in a manner that would thrust plus-end-out microtubule down the axon and minus-end-out microtubules back to the cell body [42]. However, because the long microtubules in the axon are stationary, this would only produce motion in the case of the short microtubule of the pair. Such a mechanism would not be sufficient to provide the axon with an ongoing supply of plus-end-out microtubules, but it may contribute to clearing minus-end-out microtubules back to the cell body. Other types of dynein interaction with microtubules, which include “end-on” modes as well as “side-on” modes, have been discussed in other contexts [44-47], and may also have counterparts in the axon.

Figure 4. Cytoplasmic dynein has properties that make it an effective polarity-sorting molecule for the axon.

– A. Dynein is known to be able to swivel, which is important for enabling it to polarity sort microtubules. When a short mobile microtubule moves relative to a long stationary microtubule, via a sliding-filament mechanism, the polarity orientation of the long stationary microtubule is irrelevant. The short mobile microtubule is transported relative to its polarity orientation. B. In another potential scenario, recent studies indicate that dynein has the capacity to “split-slide” microtubules, meaning that the two motor domains of a dynein complex interact with different microtubules. It is not known whether this occurs in the axon, but if it does, then the polarity orientation of both the short mobile microtubule and the long stationary microtubule would be relevant. If the microtubules are oppositely oriented, the forces would theoretically thrust the minus-end-out microtubule back to the cell body, and the plus-end-out microtubule forward down the axon. However, because the long microtubules in the axon are stationary, this would only produce motion in the case of the short microtubule of the pair. C. A short mobile microtubule can in principle interact with multiple different long microtubules surrounding it, thus optimizing the probability that the short microtubule will be transported as a sliding filament in a polarity-sorting manner as opposed to being transported as “cargo” in a manner that would not recognize the polarity orientation of the short mobile microtubule but would recognize the polarity orientation of the long immobile microtubule. Modified from Rao et. al. 2017 [29].

A trickier question is why the short microtubule does not simply move as cargo toward the minus ends of long microtubules in a fashion similar to membranous organelles moving via dynein. In other words, why does dynein (presumably via adaptor proteins) associate with the long microtubule (rather than the short microtubule) in a manner that makes dynein's motor domain available to transport the short microtubules? One possibility is that the short mobile microtubules are compositionally specialized, such that they are less compatible for dynein or its adaptor proteins to bind [48]. However, a probability argument seems more appealing. Each short microtubule is essentially surrounded by long microtubules. So, assuming that dynein is coming on and off all microtubule surfaces with roughly equal frequency, the likelihood is overwhelmingly larger of the short microtubule encountering motor domains of dynein molecules on long microtubules than it would be for the short microtubule to adhere to a dynein molecule and move along the long microtubule as cargo (figure 4C).

A potential role for kinesin-1

Kinesin-1 (kif5, conventional kinesin), the predominant plus-end-directed motor for transporting membranous organelles, has not classically been considered in the context of microtubule transport. However, a domain of kinesin-1 has recently been posited to serve as an ATP-independent microtubule-binding site that enables kinesin-1 to slide antiparallel microtubules relative to one another [49]. In studies on cultured Drosophila neurons expressing a fluorescently-tagged tubulin, live-cell imaging together with genetic manipulations suggested that the sliding of antiparallel microtubules by kinesin-1 in the cell body may contribute to the formation of axons [50, 51]. Dynein, on the other hand, was implicated by these studies in the transport of minus-end-out microtubules from the early axon back to the cell body, but not in the transport of plus-end-out microtubules into the axon [51]. In another curious difference compared to vertebrate axons, the dynein-driven retrograde transport of microtubules was concluded to occur only against the actin cytoskeleton and not against other microtubules. The relevance of these findings on the relatively short axons of the cultured insect neuron to the elongation and maintenance of vertebrate axons remains unclear. To the best of our understanding, the model put forth on the basis of these findings does not provide for an ongoing stream of motor-sorted microtubules throughout the life of the axon, but only speaks to microtubule sliding during axogenesis, or locally in the axon during regeneration after injury when antiparallel microtubules may arise at the axon's tip [52].

In a recent paper on vertebrate muscle cells, microtubule sliding was shown to occur via dynein, but could occur via kinesin-1 when dynein was depleted [53]. Consistent with this finding, computational modeling using available data on the two motors suggests that when dynein and kinesin-1 compete to slide microtubules, dynein would generally win [29]. Individual microtubules moving within vertebrate axons occasionally pause and even reverse direction, suggesting that there is an opposing force tugging on the microtubules in the opposite direction of dynein's forces. It makes sense that kinesin-1 might be the motor that generates these forces, and if it is, then kinesin-1 might be the motor (or one of the motors) that aberrantly transports microtubules in the axon when dynein is depleted. However, it seems counterintuitive that kinesin-1's ability to slide microtubules would be only counterproductive to the axon. It may be, as suggested by the studies on invertebrates as well as recent work on zebrafish, that particular events in the axon, such as growth-related challenges at the axon's tip [52] or perhaps axonal branch formation [54], benefit from the forces of antiparallel microtubule sliding by kinesin-1.

Cross-linker Proteins

One of the long-standing mysteries of the microtubule transport data is why only short microtubules undergo rapid concerted transport down the axon. We previously considered it reasonable that long microtubules are stationary because multiple dynein molecules could presumably interface between the two microtubules, some with their motor domains interacting with the first microtubule and others with their motor domains interacting with the other microtubule [55]. Thus, the forces would cancel out, leading to non-movement of long microtubules. However, our computational analyses suggested that a “winner takes all” scenario is more likely, in which movement of long microtubules would actually occur if dynein were the only factor involved [29]. Thus, a simple dynein-based mechanism is insufficient within itself to explain this aspect of the data. Introducing static cross-linkers that limit microtubule movements provides a more satisfactory simulation of the observed data [29]. By putting limits on microtubule transport, these cross-linkers can account for the length-dependence of microtubule transport, because the cross-links are transient and a certain number of them would have to accumulate over the length of the microtubule in order to impede its movement. In addition, the cross-links may also assist the system in favoring dynein-based transport of microtubules over the influence of other motors, such as kinesin-1. In other words, if the overall mobility within the microtubule array is too high, then the polarity-sorting mechanism becomes overwhelmed by what other motors can do. Precedent for this idea comes from the study on muscle cells mentioned earlier, in which depletion of an isoform of MAP4 called oMAP4 resulted in aberrant sliding of microtubules by kinesin-1 rather than normal sliding by cytoplasmic dynein, which in turn led to microtubule disorganization [53].

What are these hypothetical cross-linking proteins in the axon? Experimental depletion of a critical cross-linking protein would presumably result in movement of long microtubules as well as microtubule polarity flaws due to non-dynein motors aberrantly transporting microtubules. Neither of these have been observed when the kinesin “brakes” discussed earlier were depleted, suggesting that the relevant proteins are more likely to be static cross-linkers. In recent studies, a microtubule cross-linking protein called TRIM46, enriched in the axon initial segment but also present along the axonal shaft, was suggested to play a role in maintaining the polarity orientation of microtubules in the axons of cultured rat hippocampal neurons [56]. It was posited that TRIM46 cross-links microtubules specifically of the same orientation, and this conclusion was supported by studies on TRIM46 overexpression, which led to uniformly-oriented microtubule bundles in cells [56]. However, tau overexpression in cells also results in microtubule bundles of uniform polarity orientation [57], despite the fact that the microtubule-bundling properties of tau have no known ability to preferentially bundle microtubules of common orientation. In those tau studies, we posited that tau forms bundles of microtubules of uniform orientation in cells because of the presence in cytoplasm of “transport machinery” that sorts microtubules on the basis of their polarity orientation [57]. The same may be true for TRIM46. However, TRIM46 appears to play a special role in regulating microtubule polarity orientation not shared by tau because depletion of TRIM46 causes microtubule polarity flaws in the axons of cultured hippocampal neurons [56], whereas depletion of tau does not [16]. Indeed, partial depletion of TRIM46 from cultured rat sympathetic neurons led to an increase in microtubule sliding, with longer microtubules moving as well as short ones [29]. We suspect that the polarity flaws observed in the original study [56] resulted from lack of sufficient control over the microtubule transport system, such that non-dynein motors, presumably kinesin-1, became able to move the microtubules in the absence of TRIM46. We suspect that TRIM46 is not the only relevant cross-linking protein for axonal microtubules, with others, such as oMAP4 potentially participating as well.

What about dendrites?

Uniformly-oriented microtubule arrays are far more common in cells than arrays of mixed orientation, and even examples of mixed orientation, such as in the mitotic spindle, consist, in fact, mostly of two overlapping arrays of uniform orientation. The appeal of the polarity-sorting model for the axon is that it achieves a classic pattern of microtubule organization and does so by exploiting known self-organizing properties of microtubules and motor proteins. The question arises as to how vertebrate dendrites develop microtubule arrays of mixed orientation. One possibility is that minus-end-out microtubules are added to dendrites by local microtubule nucleation events, via gamma-tubulin and perhaps Golgi outposts [58, 59]. In axons, local nucleation of new microtubules via gamma-tubulin is limited to the sides of pre-existing microtubules by a protein called augmin, such that newly-nucleated microtubules adopt the polarity orientation of pre-existing microtubules [18] (figure 1). This presumably is not the case in dendrites if they utilize local nucleation as a means for adding minus-end-out microtubules to an array that starts out as uniformly plus end out.

In keeping with a motor-based mechanism for organizing neuronal microtubules, we have proposed that certain kinesins transport minus-end-out microtubules into developing dendrites, and then hold them there in opposition to dynein's polarity-sorting efforts. In a remarkable display of microtubule polarity sorting, when these kinesins are depleted, the minus-end-out microtubules are chased back into the cell body, and the dendrite reverts to an axonal identity [60]. These kinesins are kinesin-6 and kinesin-12, which serve the axon in a different manner (see earlier). Both of these kinesins diminish in expression in adult neurons [3, 61] and hence the mixed orientation of dendritic microtubules probably requires other factors, such as cross-linker proteins that limit microtubule sliding, to oppose the polarity-sorting properties of dynein over the life of the neuron. Whether these hypothetical cross-linkers are the same or different from those in the axon will be a matter of great interest. Another possibility for the mixed orientation in dendrites is that dendritic microtubules eventually segregate into bundles of common orientation, so that minus-end-out microtubules are no longer driven back to the cell body simply because they do not interact with oppositely-oriented microtubules. Finally, it is worth mentioning that many invertebrate dendrites contain nearly uniformly minus-end-out microtubules after undergoing a transient phase of mixed orientation [62], and this is possibly due to clearing of plus-end-out microtubules from these dendrites by kinesin-1 [63].

Concluding remarks

A single-motor polarity sorting model for generating and preserving the axon's microtubule polarity pattern is appealing in its simplicity, yet the complexity of the biological reality of a living axon could demand a more elaborate mechanism. We posit that axons evolved as direct manifestations of what cytoplasmic dynein and microtubules do when they are allowed to self-organize under the spatial constraints of an elongated cytoplasmic process. However, like any structure facing complex challenges, additional tools and building materials became necessary to accommodate axon-specific demands and constraints. Localized kinesin-1-driven antiparallel microtubule sliding, for example, may have provided a solution to certain growth-related challenges, but also introduced a risk of corrupting the microtubule polarity pattern of the axon, if not tamped back by a cross-linker such as TRIM46 or oMAP4. Boosts of gamma-tubulin-based nucleation of microtubules in some axons may have proven useful for addressing other challenges, but only if limited to the sides of pre-existing microtubules, so as not to introduce reverse-oriented microtubules. We hypothesize that a dynein-based microtubule polarity-sorting mechanism is foundational for what makes the axon an axon, but we also emphasize that such a mechanism is only the starting point of the story of how axonal microtubules are organized. The current state of our mechanistic thinking, buoyed by additional computational modeling [64], is shown in figure 5. Many exciting questions remain (see Outstanding Questions).

Figure 5. (key figure) – A dynein-based polarity sorting model for organizing microtubules in the axon.

Schematic depicting our proposed model, wherein microtubules are polarity sorted by cytoplasmic dynein, but with other molecular players (i.e. a plus-end directed motor and a cross-linker protein) introducing regulatory kinetics such as pauses and inhibition of microtubule transport. In theory, cytoplasmic dynein, by itself, has the appropriate properties to establish and maintain the nearly uniform plus-end-out polarity orientation of microtubules in the axon, by transporting plus-end-out microtubules into the axon and down its length, and transporting back to the cell body minus-end-out microtubules that might rise in the axon. However, the observed characteristics of microtubule transport and organization in the axon indicate the need for additional players. Computational modeling suggested that an opposing plus-end directed motor force (such as kinesin-1) and static cross-linkers can help explain the data. Recent experimental data indicate that a cross-linker protein called TRIM46 functions in this manner in the axon [29], and kinesin-1 is a reasonable candidate for the motor protein that provides the opposing force. Modified from Rao et. al. 2017 [29].

Trends Box.

Almost all microtubules in the axon are uniformly oriented with their plus ends out, but the question remains as to how this essential pattern is generated and preserved, in the face of potential corruption.

Polarity sorting of microtubules by molecular motor proteins has been posited as the mechanism by which the microtubule polarity pattern of the axon is established and preserved. In this mechanism, microtubules of opposite orientation are spatially separated, so that minus-end-out microtubules are cleared from the axon by transport back to the cell body and plus-end-out microtubules are conveyed into and down the axon to populate its length.

Cytoplasmic dynein is the principal motor protein that polarity sorts microtubules in the axon.

A simple polarity sorting mechanism is insufficient to explain microtubule organization in the axon, especially in light of other motors, such as kinesin-1, that may impede the dynein-based sorting process. Static microtubule cross-linking proteins may be the means by which microtubule movements are sufficiently restricted so that dynein-based polarity sorting can be effective.

Live-cell imaging and computer simulations have been instrumental in developing this model.

Outstanding Questions Box.

What are the various molecular players that modify or impinge upon the dynein-based polarity sorting of axonal microtubules?

Do the axons of different kinds of neurons utilize different formulations of the various factors involved in polarity sorting? Conceivably, such differences could depend, for instance, on axon initial segment variability across neuronal subtypes, whether or not the axon makes collateral branches, whether it has on average longer or shorter microtubules, or the particular length the axon achieves.

Might a kinesin-14 family member have some overlapping functions with cytoplasmic dynein in the polarity-sorting mechanism?

Is kinesin-1 a motor protein that can slide microtubules in vertebrate axons? If so, what useful functions does such sliding provide, and can such sliding impose the potential for microtubule polarity corruption, if not appropriately regulated?

What is the contribution of microtubule polarity flaws to neuronal malfunction or degeneration of the axon during disease and injury? Can knowledge of the polarity-sorting mechanism assist in developing therapies to improve the capacity of the axon to correct those flaws?

What specialized mechanisms exist to enable the dendrite to overcome the polarity-sorting mechanism so that it can be populated with minus-end-out microtubules as well as plus-end-out microtubules, and do these mechanisms vary for different kinds of dendrites?

Glossary

- Microtubule

architectural polymer of tubulin subunits with structural polarity. The plus end is favored over the minus end for microtubule assembly/disassembly dynamics. The polarity of the microtubule is also relevant to the directionality in which different molecular motor proteins ‘walk’ along the surface of the microtubule

- Molecular Motor Proteins

enzymes that use the energy of ATP hydrolysis to ‘walk’ along the surface of the microtubule. These proteins can, for instance, convey cargo along the microtubule's length, or cause the microtubule itself to move against other structures

- Microtubule Transport (also referred to as microtubule sliding)

the movement of microtubules by molecular motor proteins. The term “microtubule transport” has been used more often to refer to longer concerted bouts of movement of short microtubules, whereas “microtubule sliding” has more often been used to refer to shorter bouts of microtubule movement, and also often refers to longer microtubules and to antiparallel microtubule movements. Despite these nuances in terminology, the two terms (microtubule transport and microtubule sliding) are interchangeable

- Cytoplasmic dynein

a molecular motor protein that walks toward the minus end of the microtubule

- Kinesins

Molecular motors, most of which walk toward the plus end of the microtubule, except for the kinesin-14, which walks toward the minus end of the microtubule

- Microtubule-severing proteins

enzymes (such as katanin and spastin) that use the energy of ATP hydrolysis to tug a tubulin subunit from the microtubule and thereby cause the microtubule to break

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- tdEos

tandem-dimer Eos protein, a protein that that changes from green to red fluorescence emission upon ≈390 nm exposure of the green fluorescence; the photoconversion from green to red occurs because of a light-induced alteration involving a break in the peptide backbone next to the chromophore

- RNA interference

ribonucleic acid interference, a mechanism by which RNA molecules inhibit gene expression by targeting and disrupting the processing of specific mRNA molecules

- TRIM46

tripartite motif-containing protein 46, a member of the tripartite motif containing (TRIM) protein family that is thought to have a unique role in microtubule organization

- oMAP4

splice variant of the MAP4 (microtubule-associated protein 4) gene which has been implicated in regulating microtubule sliding by molecular motor proteins

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Conde C, Caceres A. Microtubule assembly, organization and dynamics in axons and dendrites. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(5):319–32. doi: 10.1038/nrn2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidemann SR, Landers JM, Hamborg MA. Polarity orientation of axonal microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1981;91(3):661–665. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baas PW, Lin S. Hooks and comets: the story of microtubule polarity orientation in the neuron. Developmental neurobiology. 2011;71(6):403–418. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharp DJ, et al. Identification of a microtubule-associated motor protein essential for dendritic differentiation. The Journal of cell biology. 1997;138(4):833–843. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yau KW, et al. Dendrites in vitro and in vivo contain microtubules of opposite polarity and axon formation correlates with uniform plus-end-out microtubule orientation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2016;36(4):1071–1085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2430-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baas PW, Black MM, Banker GA. Changes in Microtubule Polarity Orientation during the Development of Hippocampal-Neurons in Culture. Journal of Cell Biology. 1989;109(6):3085–3094. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baas PW, et al. Polarity Orientation of Microtubules in Hippocampal-Neurons -Uniformity in the Axon and Nonuniformity in the Dendrite. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(21):8335–8339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baas PW, Ahmad FJ. The transport properties of axonal microtubules establish their polarity orientation. The journal of cell biology. 1993;120(6):1427–1437. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.6.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad FJ, et al. Cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin are required for the transport of microtubules into the axon. The Journal of cell biology. 1998;140(2):391–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao AN, et al. Sliding of centrosome-unattached microtubules defines key features of neuronal phenotype. J Cell Biol. 2016:jcb. 201506140. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201506140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Y, et al. Role of cytoplasmic dynein in the axonal transport of microtubules and neurofilaments. J Cell Biol. 2005;168(5):697–703. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu M, et al. Kinesin-12, a mitotic microtubule-associated motor protein, impacts axonal growth, navigation, and branching. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(44):14896–14906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3739-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Brown A. Rapid movement of microtubules in axons. Current Biology. 2002;12(17):1496–1501. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers KA, Baas PW. Kinesin-5 regulates the growth of the axon by acting as a brake on its microtubule array. J Cell Biol. 2007;178(6):1081–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baas PW, Vidya Nadar C, Myers KA. Axonal transport of microtubules: the long and short of it. Traffic. 2006;7(5):490–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiang L, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor elicits formation of interstitial axonal branches via enhanced severing of microtubules. Molecular biology of the cell. 2010;21(2):334–344. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-09-0834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baas PW, Mozgova OI. A novel role for retrograde transport of microtubules in the axon. Cytoskeleton. 2012;69(7):416–425. doi: 10.1002/cm.21013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sánchez-Huertas C, et al. Non-centrosomal nucleation mediated by augmin organizes microtubules in post-mitotic neurons and controls axonal microtubule polarity. Nature communications. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dent EW, et al. Reorganization and movement of microtubules in axonal growth cones and developing interstitial branches. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19(20):8894–8908. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08894.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsui HcT, et al. Novel organization of microtubules in cultured central nervous system neurons: formation of hairpin loops at ends of maturing neurites. Journal of Neuroscience. 1984;4(12):3002–3013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-12-03002.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J, Akhmanova A. Microtubule-Organizing Centers. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 20170 doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishita M, et al. Regulatory mechanisms and cellular functions of non-centrosomal microtubules. The Journal of Biochemistry. 2017:mvx018. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvx018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heald R, et al. Self-organization of microtubules into bipolar spindles around artificial chromosomes in Xenopus egg extracts. Nature. 1996;382(6590):420. doi: 10.1038/382420a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janson ME, et al. Crosslinkers and motors organize dynamic microtubules to form stable bipolar arrays in fission yeast. Cell. 2007;128(2):357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nédélec F, Surrey T, Karsenti E. Self-organisation and forces in the microtubule cytoskeleton. Current opinion in cell biology. 2003;15(1):118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sumino Y, et al. Large-scale vortex lattice emerging fromcollectively moving microtubules. Nature. 2012;483(7390):448. doi: 10.1038/nature10874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walczak CE, et al. A model for the proposed roles of different microtubule-based motor proteins in establishing spindle bipolarity. Current biology. 1998;8(16):903–913. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White D, et al. Microtubule patterning in the presence of moving motor proteins. J Theor Biol. 2015;382:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao AN, et al. Cytoplasmic Dynein Transports Axonal Microtubules in a Polarity-Sorting Manner. Cell Reports. 2017;19(11):2210–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myers KA, Baas PW. Kinesin-5 regulates the growth of the axon by acting as a brake on its microtubule array. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;178(6):1081–1091. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konzack S, et al. Swimming against the tide: mobility of the microtubule-associated protein tau in neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(37):9916–9927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0927-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zemel A, Mogilner A. Motor-induced sliding of microtubule and actin bundles. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2009;11(24):4821–4833. doi: 10.1039/b818482h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazel T, et al. Direct observation of microtubule pushing by cortical dynein in living cells. Molecular biology of the cell. 2014;25(1):95–106. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-07-0376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dillman JF, III, et al. Functional analysis of dynactin and cytoplasmic dynein in slow axonal transport. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16(21):6742–6752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06742.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abal M, et al. Microtubule release from the centrosome in migrating cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;159(5):731–737. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baas PW. Strategies for studying microtubule transport in the neuron. Microscopy research and technique. 2000;48(2):75–84. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000115)48:2<75::AID-JEMT3>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin S, et al. Mitotic motors coregulate microtubule patterns in axons and dendrites. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(40):14033–14049. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3070-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng Y, et al. Dynein is required for polarized dendritic transport and uniform microtubule orientation in axons. Nature cell biology. 2008;10(10):1172. doi: 10.1038/ncb1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arthur AL, et al. Dendrite arborization requires the dynein cofactor NudE. J Cell Sci. 2015;128(11):2191–2201. doi: 10.1242/jcs.170316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roossien DH, Lamoureux P, Miller KE. Cytoplasmic dynein pushes the cytoskeletal meshwork forward during axonal elongation. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(16):3593–3602. doi: 10.1242/jcs.152611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klinman E, Tokito M, Holzbaur EL. CDK5-dependent activation of dynein in the axon initial segment regulates polarized cargo transport in neurons. Traffic. 2017 doi: 10.1111/tra.12529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanenbaum ME, Vale RD, McKenney RJ. Cytoplasmic dynein crosslinks and slides anti-parallel microtubules using its two motor domains. Elife. 2013;2:e00943. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasaka TP, Myers KA, Baas PW. Role of actin filaments in the axonal transport of microtubules. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(50):11291–11301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3443-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samora CP, et al. MAP4 and CLASP1 operate as a safety mechanism to maintain a stable spindle position in mitosis. Nature Cell Biology. 2011;13(9):1040–1050. doi: 10.1038/ncb2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akhmanova A, van den Heuvel S. Tipping the spindle into the right position. J Cell Biol. 2016:jcb. 201604075. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201604075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dehmelt L. Cytoskeletal self-organization in neuromorphogenesis. Bioarchitecture. 2014;4(2):75–80. doi: 10.4161/bioa.29070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gusnowski EM, Srayko M. Visualization of dynein-dependent microtubule gliding at the cell cortex: implications for spindle positioning. The Journal of cell biology. 2011;194(3):377–386. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baas PW. Microtubule stability in the axon: new answers to an old mystery. Neuron. 2013;78(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jolly AL, et al. Kinesin-1 heavy chain mediates microtubule sliding to drive changes in cell shape. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(27):12151–12156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004736107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu W, et al. Initial neurite outgrowth in Drosophila neurons is driven by kinesin-powered microtubule sliding. Current Biology. 2013;23(11):1018–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.del Castillo U, et al. Interplay between kinesin-1 and cortical dynein during axonal outgrowth and microtubule organization in Drosophila neurons. Elife. 2015;4:e10140. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.del Castillo U, et al. Pavarotti/MKLP1 regulates microtubule sliding and neurite outgrowth in Drosophila neurons. Current Biology. 2015;25(2):200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mogessie B, et al. A novel isoform of MAP4 organises the paraxial microtubule array required for muscle cell differentiation. Elife. 2015;4:e05697. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee TJ, et al. The kinesin adaptor Calsyntenin-1 organizes microtubule polarity and regulates dynamics during sensory axon arbor development. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2017;11 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baas PW, Matamoros AJ. Inhibition of kinesin-5 improves regeneration of injured axons by a novel microtubule-based mechanism. Neural regeneration research. 2015;10(6):845. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.158351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Beuningen SF, et al. TRIM46 controls neuronal polarity and axon specification by driving the formation of parallel microtubule arrays. Neuron. 2015;88(6):1208–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baas PW, Pienkowski TP, Kosik KS. Processes induced by tau expression in Sf9 cells have an axon-like microtubule organization. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1991;115(5):1333–1344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen MM, et al. Γ-tubulin controls neuronal microtubule polarity independently of Golgi outposts. Molecular biology of the cell. 2014;25(13):2039–2050. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-09-0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Delandre C, Amikura R, Moore AW. Microtubule nucleation and organization in dendrites. Cell Cycle. 2016;15(13):1685–1692. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1172158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu W, et al. Depletion of a microtubule-associated motor protein induces the loss of dendritic identity. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(15):5782–5791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05782.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferhat L, et al. Expression of the mitotic motor protein CHO1/MKLP1 in postmitotic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10(4):1383–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rolls MM. Neuronal polarity in Drosophila: sorting out axons and dendrites. Developmental neurobiology. 2011;71(6):419–429. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yan J, et al. Kinesin-1 regulates dendrite microtubule polarity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Elife. 2013;2:e00133. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Craig EM, et al. Polarity Sorting of Axonal Microtubules: A Computational Study. Mol Biol Cell. 2017 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McKinney SA, et al. A bright and photostable photoconvertible fluorescent protein. Nature methods. 2009;6(2):131–133. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]