Abstract

Background

Throughout the human aging lifespan, neurons acquire an unusually high burden of wear and tear; this is likely why age is considered the strongest risk factor for the development of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Von Economo neurons (VENs) are rare, spindle-shaped cells mostly populated in anterior cingulate cortex. In a prior study, “SuperAgers” (individuals older than 80 years of age with outstanding memory ability) showed higher VEN densities compared to elderly controls with average memory, and those with amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI). The intrinsic vulnerabilities of these neurons are unclear, and their contribution to neurodegeneration is unknown. The current study investigated the influence of age and the severity of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) on VEN density.

Methods

VEN and total neuronal densities were quantitated using unbiased stereological methods in the anterior cingulate cortex of postmortem samples from the following subject groups: younger controls (age 20–60), SuperAgers, cognitively average elderly controls (age 65+), individuals diagnosed antemortem with aMCI, and individuals diagnosed antemortem with dementia of AD (N=5, per group).

Results

The AD group showed significantly lower VEN density compared to younger and older controls (p<0.05), but not compared to the aMCI group, and VENs bearing neurofibrillary tangles were discovered in AD cases. The aMCI group showed lower VEN density than elderly controls, but this was not significant. There was a significant negative correlation between VEN density and Braak stages of AD (p<0.001). Consistent with prior findings, SuperAgers showed highest mean VEN density, even when compared to younger cases.

Conclusions

VENs in human anterior cingulate cortex are vulnerable to AD pathology, particularly in later stages of pathogenesis. Their densities do not change throughout aging in individuals with average cognition, and they are more numerous in SuperAgers.

Search Terms: Alzheimer’s disease, Von Economo Neurons, Cognitive Aging, Neurodegeneration

INTRODUCTION

Age is the strongest risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), likely due to typical “wear-and-tear” that occurs in post-mitotic neurons across the human lifespan. The typical dementia of AD is preceded by an amnestic mild cognitive impairment stage (aMCI) where both AD pathology and cognitive impairment are less pronounced. What remain unknown are the intrinsic vulnerabilities of specific neuronal subpopulations that undergo neurodegeneration and potentially contribute to cognitive decline across the lifespan.

The great anatomists of the 19th and 20th century—Vladimir Betz (1881), Carl Hammarberg (1895), Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1896) and Constantin von Economo (1925)—were intrigued by the odd-looking “spindle-shaped” brain cells of the cerebral cortex recently renamed “von Economo neurons” (VENs), after von Economo and Koskinas (1925) who carried out a detailed cytoarchitectonic study of these cells1. In a more current description, VENs are characterized as slender, apical, and bipolar neurons2 that are localized to the anterior cingulate cortex, frontal portions of insula, and orbitofrontal cortices3. Studies have shown VENs to be present in other cortical regions in low density including the subiculum and entorhinal cortex4, superior frontal cortex5, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex6. These cells have regained recognition in the last decade as they were found to be absent or dysmorphic in various disease processes such as autism7, schizophrenia8, and agenesis of the corpus callosum9; these findings, however, were met with contradictory evidence (see Cauda et al., 2012 for review). In a series of studies, VENs were also shown to be selectively reduced in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia11 but not significantly in Alzheimer’s disease, in which VENs were found to be comparable to age-matched controls12. The reduction of VENs in neurodegenerative disorders is of particular interest as it suggests a link between pathogenesis, cognitive function, and selective vulnerability of certain neuronal populations.

These neurons were also thought to selectively appear in phylogenetically complex species (for review see Raghanti et al., 2015). In one study, the volume of VENs was correlated with relative brain size5 leading to the speculation that the emergence of VENs in species with large brains, including hominids, may support complex higher-order cognitive functions, such as social affiliative behaviors. In a prior study, we quantitated anterior cingulate VENs in a group of cognitive SuperAgers, individuals over age 80 with memory capacity that is greater-than-or-equal-to individuals 20–30 years their junior. We found that VEN density in SuperAgers was significantly higher than in age-matched, elderly individuals with “average” cognitive abilities, and individuals at the aMCI stage of Alzheimer pathology14. These findings suggested that VENs might be vulnerable to AD pathology and that their presence in higher densities may have some yet-to-be-explained relationship to the high memory capacity of SuperAgers.

The current study investigated differences in the density of VENs and the ratio of VENs to total density of cingulate neurons in relationship to age and more severe stages of AD pathology. We studied 25 human autopsied cases reflecting five distinct states of age and cognition: young cognitively-average individuals, elderly cognitively-average individuals, SuperAgers, individuals at the aMCI stage of AD and the dementia of AD. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate age-related changes in VEN integrity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Post-mortem Specimens

Cases obtained from pathologists across the country including the Northwestern University Alzheimer’s Disease Center Brain Bank, were surveyed to identify 5 right-handed cases (per group) that met strict study criteria for inclusion into the following five groups: a young cognitively-normal control group, elderly cognitively-average control group, SuperAgers, a group of individuals diagnosed antemortem with aMCI, and a group of individuals with clinically confirmed dementia of the Alzheimer type and pathologic diagnosis of AD (see below). Cases were required to lack clinical evidence or history of other neurologic or psychiatric disease; substance use history was not available for review. For cases in which neuropsychological test performance were unavailable, chart review was undertaken, and when needed, information was obtained from the next of kin if available. Samples from representative brain regions of each case were surveyed qualitatively by an expert neuropathologist (Eileen Bigio, MD) and found to be free of pathologies other than amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Braak staging15 was also surveyed in each case to identify tangle involvement in transentorhinal/entorhinal cortex, other limbic cortical areas, and neocortical regions. To assess AD pathology, specific antibodies to tau (AT8, Pierce-Endogen, Rockford, IL, USA) and beta-amyloid (4G8, Signet, Dedham, MA, USA) were used to visualize neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques, respectively. The study was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration http://www.wma.net/e/policy/17-c_e.html). See Table 1 for case information.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cases.

| Case | Age at Death (years) | Sex | PMI (hours) | Brain Weight (gms) | Braak Staging |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young 1 | 50 | F | 48 | 1150 | 0 |

| Young 2 | 61 | F | 22 | 1080 | I |

| Young 3 | 57 | F | 6 | 1100 | 0 |

| Young 4 | 45 | M | 13 | 1650 | 0 |

| Young 5 | 26 | M | 8 | 1560 | 0 |

| SuperAger 1 | 87 | F | 11 | 1090 | III |

| SuperAger 2 | 90 | F | 4.5 | 1100 | II |

| SuperAger 3 | 90 | F | 4 | 990 | III |

| SuperAger 4 | 81 | F | 9.5 | 1269 | 0 |

| SuperAger 5 | 95 | F | 5 | 1241 | 0–I |

| Elderly 1 | 95 | F | 3.25 | 1096 | III |

| Elderly 2 | 89 | F | 9 | 1180 | II |

| Elderly 3 | 72 | F | 7.5 | 1310 | III–IV |

| Elderly 4 | 88 | M | 12 | 1250 | III–IV |

| Elderly 5 | 89 | F | 6 | 1160 | III–IV |

| aMCI 1 | 89 | F | 4.5 | 1280 | II |

| aMCI 2 | 99 | F | 5 | 1060 | IV |

| aMCI 3 | 92 | F | 3.5 | 1084 | IV |

| aMCI 4 | 90 | M | 3 | 1380 | III |

| aMCI 5 | 92 | M | 4.5 | 1100 | V |

| AD 1 | 80 | M | 26 | NA | V |

| AD 2 | 72 | M | 7 | NA | VI |

| AD 3 | 87 | M | 13 | 1000 | VI |

| AD 4 | 80 | F | 25 | NA | V |

| AD 5 | 83 | F | 23 | NA | VI |

PMI = Post mortem interval; Braak staging followed published guidelines (Braak & Braak, 1991, 1995); NA = Data not available.

Inclusion Criteria

Cognitive SuperAgers

All cases considered “Cognitive SuperAgers” were identified based on strict cognitive criteria determined at the visit closest to death. Three cases from our sample were community-dwelling participants that were recruited through the Northwestern University Cognitive SuperAging Study and who had agreed to brain donation. They were required to be ≥age 80 and meet psychometric criteria on a battery of neuropsychological tests, which were chosen for their relevance for cognitive aging and their sensitivity to detect clinical symptoms associated with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type16. The delayed recall score of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) was used as a measure of episodic memory and SuperAgers were required to perform at or above average normative values for individuals in their 50s and 60s (midpoint age=61; RAVLT delayed-recall raw score≥9; RAVLT delayed-recall scaled score≥10). A 30-item version of the Boston Naming Test (BNT-3018), Trail Making Test Part B (TMT Part B19), and Category Fluency test (“Animals”20), a semantic memory test sensitive to early stages of AD dementia, were used to measure cognitive function in non-memory domains. On the BNT-30, TMT Part B, and Category Fluency, SuperAgers were required to perform within or above one standard deviation of the average range according to published normative values based on age and demographic factors21–23. In one case, neuropsychological data were available from the telephone interview for cognitive status24, which includes immediate and delayed recall of a 10-word list; on this task, subjects were required to recall at least 9/10 words on the delayed recall portion. The final SuperAging case was included based on the delayed recall memory performance from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) word list20. Data from this group was previously published in Gefen et al., 2015.

Elderly Cognitively-Average Individuals

Cognitively-average elderly individuals, all ≥age 80, were identified through the Northwestern University Alzheimer’s Disease Center and were determined to be “average” compared to their same-age peers based on neuropsychological performance. Elderly controls were required to fall within one standard deviation of the average range for their age and education21–23. In some cases, memory scores closest to death from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease were used to determine cognitive status20. Criteria are also in accordance with the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) criteria for elderly individuals considered “not demented”25.

Young Cognitively-Normal individuals

Ages of the young cognitively-normal cases ranged from 26–61 years. Clinical records were available for each participant and were assessed carefully for evidence of cognitive deficits. If the clinical history did not definitively validate normal cognitive function, this information was obtained from the next of kin.

Individuals with aMCI Diagnosis

Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI) cases were identified based on the criteria proposed by the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) 25. aMCI cases were required to show clear impairment on neuropsychological tests of memory, and no impairment in other cognitive domains.

Individuals with postmortem AD

A final group of cases were identified that were clinically diagnosed as having dementia of the Alzheimer type and showed post-mortem AD pathology, based on the histopathologic processing outlined below, according to NIA-AA guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease 26 and consistent with Braak stages V or VI15.

Tissue Processing and Histopathology

Post-mortem intervals ranged from 3–48 hours. Specimens were cut into 3–4cm coronal blocks and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30–36 hours at 4°C, then taken through sucrose gradients (10–40% in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for cryoprotection and stored at 4°C. Blocks were sectioned at 40 μm on a freezing microtome and stored in 0.1M phosphate buffer containing 0.02% sodium azide at 4°C until use. Samples were taken from Brodmann area (BA) 25 (parolfactory cortex/rostral anterior cingulate) and BA 24 (caudal anterior cingulate). Up to 6 sections (intersection interval=24 or 54) in each cortical region were stained for Nissl substance with .5–1.0% cresyl violet used to visualize neurons, including VENs in cingulate cortex. In cases with severe AD pathology, anterior cingulate regions were surveyed to identify tangle-bearing VENs in pre-stained sections available with Alz5027, antiserum to paired helical filaments (PAM28) or the monoclonal antibody PHF-1 which recognizes tau phosphorylated at Ser396/404, Thr18129. All cases were qualitatively examined for tau-stained tangles and pre-tangles, including VENs. This study did not attempt to examine laterality effects among VENs in cingulate cortex.

Quantitative Analysis of Neuronal Density

For each case, anterior cingulate regions were traced at 4X and analyzed at 40X magnification by a single individual (T.G) who was blinded to case information and group affiliation. Stereological analysis was carried out on up to 6 sections according to procedures previously described in detail14, 30, employing the fractionator method and the StereoInvestigator software (MicroBrightField). The sections used in analysis were treated as adjacent sections, allowing determination of neuronal density in the total volume within sections; samples were obtained from both Brodmann areas 25 and 24, despite a prior subfield effect reported in Gefen et al., 2015. The cingulate cortex in each section was traced from the cortical surface to the white matter. The top and bottom 2μm of each section were set as guard height. The dimensions of the counting frame were 170 × 170μm chosen based on data that was generated algorithmically with a Schmitz-Hof coefficient of error of approximately 0.15. Stereological counts obtained were expressed as mean counts per cubic millimeter, based on planimetric calculation of volume by the fractionator software. Counts were expressed as density of neurons per mm3. Estimated counts included: density of VENs, density of total neurons, and the ratio of VEN density to total neuronal density to account for VEN concentration relative to baseline total neurons. VENs were defined by their distinct morphology: thin, elongated cell body and long, bipolar dendrites and location in the deep cortical layers2. Mean density was compared between the five groups to evaluate significant differences.

Statistical Analysis of Stereological Data

Three separate one-way, ANOVAs with post-hoc Bonferonni corrections for multiple comparisons were conducted for anterior cingulate VEN density, total neuronal density (including VENs), and ratio of VEN/total neuronal density, to analyze comparisons between cognitively-average elderly individuals, young cognitively-normal individuals, individuals with an aMCI diagnosis, and AD. Data passed the test of normality (Kolmogorov and Smirnov) and therefore parametric ANOVAs were used. We subsequently compared VEN density in SuperAgers to all other groups. Spearman correlations were performed between age at death, VEN density, and neuronal density in the young cognitively-normal group and cognitively-average elderly group. Spearman correlation was conducted between VEN density, neuronal density, ratio of VEN/total neuronal density and Braak staging in all subject groups combined (N=25). Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS (v. 23) software and the GraphPad Prism software, v. 5.0. The probability for significant effects was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic Information

As expected, the mean age of the young cognitively-normal individuals (M=47.8; SD=13.7) was significantly lower than the mean age of SuperAgers (M=88.6; SD=5.1), cognitively-average elderly individuals (M=86.6; SD=8.6), individuals with aMCI (M=92.4; SD=3.9), and individuals with severe postmortem AD (M=80.4; SD=5.5) (p< 0.001); there were no other significant differences in age between groups. There were no significant differences in post-mortem interval (PMI) across groups (p>0.05). Our sample was predominantly female (17 female vs. 8 male specimens). See Table 1.

Stereological Quantitation of VENs and Total Neuronal Densities

There were no significant correlations between age at death and VEN or neuronal densities across the young cognitively-normal and the cognitively-average elderly groups.

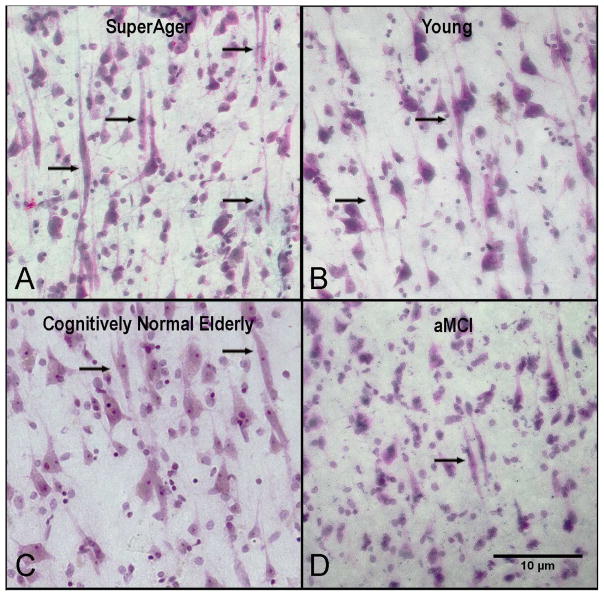

Overall mean density of VENs was significantly higher in the SuperAging group, compared to the elderly control group (p<0.05), the aMCI group (p<0.01), the dementia/AD group (p<0.001), and even young cognitively-normal individuals (p<0.05). Within the other 4 groups, the highest density of VENs and total neuronal density were found in cognitively-normal young individuals, followed by cognitively-average elderly individuals, individuals with aMCI, and individuals with the dementia of AD (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Abundance of VENs in SuperAgers compared to young, cognitively-normal elderly, and aMCI groups.

Nissl stain at 20× magnification in anterior cingulate shows an abundance of VENS (black arrows) in a SuperAger (A) compared with young control (B), a cognitively-normal elderly control (C) and an individual with aMCI (D). Scale bar at 10 μm.

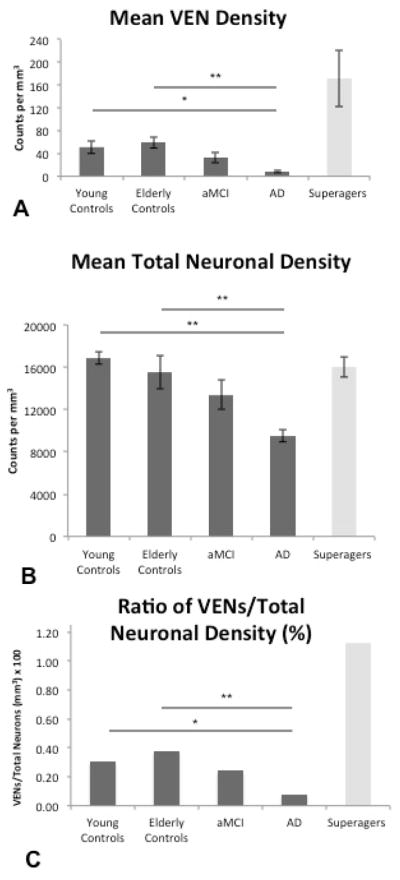

In the dementia/AD group, VEN density was significantly lower than the young (p<0.05) and elderly (p<0.01) control groups. There were trends of lower density in the aMCI group when compared to the elderly group, and higher density compared to the dementia/AD group, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2A). Similar patterns were observed when accounting for total neuronal density (mean per group of total VENs/total neuronal density) (Figure 2C). Total neuronal density in cingulate cortex, including VENs, was significantly lower in the AD group compared to young cognitively-normal individuals (p<0.01) and cognitively-average elderly individuals (p<0.01), but not the aMCI group (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Heights of the bars represent mean estimated VEN density, total neuronal density, and ratio of VEN density/total neuronal density, per cubic millimeter in all five subject groups (n = 5 per group) in the anterior cingulate cortex. Error bars represent standard error. (A) Consistent with prior findings (Gefen et al. 2015), SuperAgers showed higher VEN density compared to all groups. The following relationships were found among the other 4 groups: AD subjects showed significantly lower VEN density compared to young controls and cognitively-normal controls; there were no differences between aMCI subjects and AD subjects or aMCI subjects and elderly controls. In addition, there were no significant differences between the cognitively normal young and normal older groups. (B) Highest total neuronal density was found in young controls, followed by elderly controls, aMCI subjects, and AD subjects; there were no significant differences between elderly and young controls. Neuronal density in SuperAgers was at levels comparable to young and old cognitively average subjects. (C) When total neuronal count was accounted for, VEN distributions (illustrated as the ratio of VEN density to total neuronal density × 100) remained similar to the distribution illustrated in VEN counts alone. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

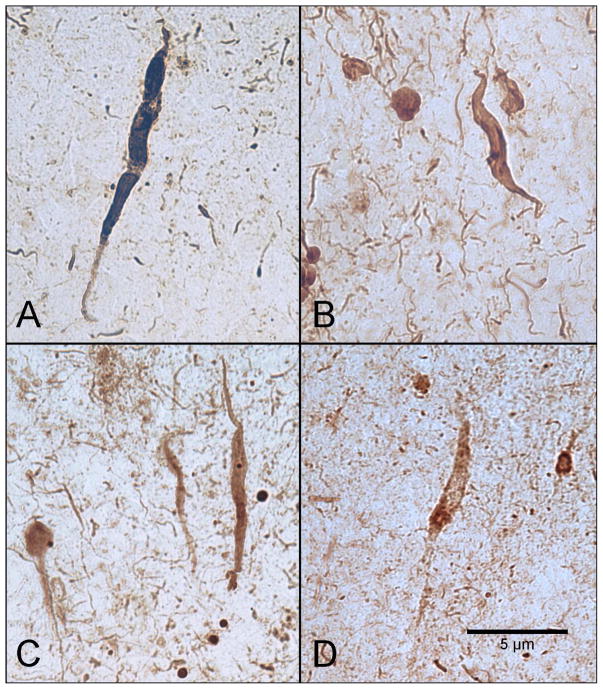

Qualitative Analysis of VEN Tangles

We reported previously on five aMCI cases stained with Thioflavin-S in which there were no apparent tangle-bearing VENs visualized in cingulate cortical regions 14. For this study we surveyed five cases with dementia and end-stage post-mortem AD pathology (Braak stage V or VI) for the presence of tangle-bearing VENs within anterior cingulate cortex. All 5 AD cases showed very sparse tangle-bearing VENs in layer V, each stained with PHF-1, Alz50, or PAM (Figure 3). In some sections, tangle-bearing VENs appeared particularly dysmorphic (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Tangle/pre-tangle-bearing von Economo Neurons (VENs) in anterior cingulate cortex of postmortem cases with Alzheimer disease.

Very sparse, infrequent VENs are demonstrated at 40x magnification in vertical orientation and are characterized based on their slender morphology and bipolar dendritic architecture. In some cases, VENs appeared dysmorphic. Tangle/pre-tangle-bearing VENs are visualized with PHF-1 (A & B), PAM (C), and Alz50 (D). Scale bar at 5 μm.

Braak staging of neurofibrillary tangles was performed using Thioflavin-S and tau stained sections. When all 25 cases were included in analyses, a significant negative correlation was found between VEN density and Braak staging (r2=−.603, p<0.001), where higher Braak staging (i.e. increased severity of tangle pathology) was related to lower VEN density. The same pattern held true for Braak staging and total neuron density (r2 =−.608, p<0.001) and Braak staging and ratio of VEN/total neuronal density (r2 =−.519, p<0.01). These patterns were maintained when the SuperAging group was excluded from analyses, suggesting that correlational results were not driven by uniquely high numbers of VENs demonstrated in the SuperAging group.

DISCUSSION

Our study sought to determine age-related changes in VEN density across cognitive aging trajectories in an attempt to make inferences about VEN vulnerability. We investigated 25 postmortem specimens from 5 groups of subjects: cognitively normal young, cognitively normal elderly, aMCI, and dementia of AD (N=5 per group). The group as a whole spanned a broad range of tangle pathology from Braak stages 0 to VI. In the elderly groups, the Braak stages tended to be higher along a sequence from SuperAgers to average elderly, aMCI, and dementia, but there were also overlap. We discovered tangle-bearing VENs in cases where AD pathology led to dementia. These cases showed a drastic reduction of VENs compared to cognitively normal groups of young and elderly. We also found a significant negative correlation between VENs and Braak stages, further demonstrating the vulnerability of these neurons to the neurofibrillary degeneration of AD. There were no significant differences between aMCI and cognitively normal elderly in the density of VENs, total neurons and ratio of VENs to total neurons. Moreover, our earlier findings did not reveal the presence of VEN tangles in aMCI. These observations suggest that VEN vulnerability to AD may start in later stages of the pathological cascade leading to dementia.

In prior brain imaging studies of SuperAgers, we had found greater thickness of the anterior cingulate cortex compared to 50-to-60-year-old cognitively average adults14, 31, SuperAgers also had higher densities of cingulate VENs compared to cognitively average elderly and those in the aMCI stage of AD14. Here, we strengthen these findings by showing a higher density of these cells in SuperAgers, not only when compared with cognitively average elderly, but also when compared with the cognitively average younger subjects. There are two possibilities for explaining higher densities of VENs in SuperAgers. The first is postnatal neurogenesis of VENs, which has been previously proposed32, 33. The second and more plausible option is that SuperAgers have constitutionally higher densities of VENs at birth or during post-natal stages of early cortical development. Our current findings did not show a correlation between age at death and VEN or neuronal density; indeed, a larger sample size of cases per age group would allow for investigation of a more definitive relationship.

In 1885, Carl Hammarberg performed a quantitative study of layer V spindle neurons in the prefrontal cortex in 9 post-mortem brains from subjects who had demonstrated varying degrees of “feeble-mindedness”. He concluded that “numerical deficiencies” of these cells were a constituent element of cognitive deficiency34. Within the last century, research into the morphological and functional significance of VENs has evolved quite drastically. Initially VENs were thought to exist solely in great apes and hominids5. The discovery of VENs in additional species such as cetaceans (e.g. humpback whale), perissodactyls (e.g. black rhinoceros), and afrotherians (e.g. Indian elephant) led to the suggestion that VENs are peculiar to “large-brained” species, which are dependent for survival on particularly complex cognitive and affiliative behaviors13, 35. In humans, there is evidence that VENs are vulnerable to neurodevelopmental and psychiatric illnesses7, 8. Because of the density and location of these neurons within anterior limbic regions 36, a number of studies have investigated VEN density in neurodegenerative disease, including Alzheimer’s disease and behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) 37,38. In one study, Seeley et al., (2006), reported a selective decline of VENs in the bvFTD, specifically a reduction of 74% compared with neighboring cingulate pyramidal neurons, and showed a relative sparing of VENs in cases with dementia and postmortem AD pathology. Santillo et al., (2013) also showed a significant reduction of VENs in cases with postmortem frontotemporal lobar degeneration (tauopathy, TDP-43, and FUS), and while AD patients showed a 30% reduction of VENs compared with normal controls, this finding was statistically non-significant.

This report is the first to describe tangle-bearing VENs in the cingulate cortex of AD. Significant negative correlations between Braak staging of neurofibrillary tangles and VEN density appear to highlight the potential contribution of AD pathology to loss of VEN integrity. Corkscrew and twisted tangle-bearing VEN morphologies were encountered in the AD group, similar to what was previously reported in cases with frontotemporal lobar degeneration11. Our findings, however, were in contrast to prior findings, which showed extensive VEN loss in FTD but relative sparing in AD. It is possible that disparate findings may be due to methodological differences.

The mechanism of VEN degeneration in AD is not known, although tangle formation may figure prominently in this process. Prior studies have examined the biochemical identity of these cells40–42, while others have explored the functional connectivity of VEN-bearing anatomic regions 10. Still, the putative circuits in which VENs are involved are largely unknown. The recent discovery of VENs in macaques 43 and other terrestrial mammals may in time allow for further clarification of the neuroanatomic and functional properties of these fascinating cells in normal cognition and in disease states.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Von Economo neurons (VENs) are rare cells found in human anterior cingulate cortex.

VEN densities do not change throughout aging in individuals with average cognition.

“SuperAgers” (age 80+) show higher density of VENs than younger cases (age 20–60).

VENs in anterior cingulate cortex are vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG045571; T32 AG20506), the Northwestern University Alzheimer’s Disease Center (AG13854), The Davee Foundation, and the Florane and Jerome Rosenstone Fellowship.

Footnotes

Statistical analysis conducted by Tamar Gefen, PhD.

Authors’ Disclosures: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Von Economo C, Koskinas G. Die Cytoarchitectonik der Hirnrinde des erwachsenen. Menschen: Springer; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson KK, Jones TK, Allman JM. Dendritic architecture of the von Economo neurons. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1107–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allman JM, Tetreault NA, Hakeem AY, Park S. The von economo neurons in apes and humans. Am J Hum Biol. 2011;23:5–21. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ngowyang G. Neuere Befunde ü ber die Gabelzellen. Cell Tissue Research. 1936;25:236–239. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimchinsky EA, Gilissen E, Allman JM, Perl DP, Erwin JM, Hof PR. A neuronal morphologic type unique to humans and great apes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5268–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fajardo C, Escobar MI, Buritica E, et al. Von Economo neurons are present in the dorsolateral (dysgranular) prefrontal cortex of humans. Neurosci Lett. 2008;435:215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos M, Uppal N, Butti C, et al. von Economo neurons in autism: a stereologic study of the frontoinsular cortex in children. Brain Res. 2011;1380:206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brune M, Schobel A, Karau R, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of suicide in psychosis: the possible role of von Economo neurons. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufman JA, Paul LK, Manaye KF, et al. Selective reduction of Von Economo neuron number in agenesis of the corpus callosum. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:479–489. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cauda F, Torta DM, Sacco K, et al. Functional anatomy of cortical areas characterized by Von Economo neurons. Brain Struct Funct. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seeley WW, Carlin DA, Allman JM, et al. Early frontotemporal dementia targets neurons unique to apes and humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:660–667. doi: 10.1002/ana.21055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim EJ, Sidhu M, Gaus SE, et al. Selective Frontoinsular von Economo Neuron and Fork Cell Loss in Early Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia. Cerebral Cortex. 2011 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghanti MA, Spurlock LB, Uppal N, Sherwood CC, Butti C, Hof PR. Von Economo Neurons. In: Toga A, editor. Brainmapping: An Encyclopedic Reference. USA: Elsevier Inc; 2015. pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gefen T, Peterson M, Papastefan ST, et al. Morphometric and histologic substrates of cingulate integrity in elders with exceptional memory capacity. J Neurosci. 2015;35:1781–1791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2998-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:960–969. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318232a379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weintraub S, Wicklund AH, Salmon DP. The neuropsychological profile of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012;2:a006171. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt M. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test: A Handbook. Los Angeles Western Psychological Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saxton J, Ratcliff G, Munro CA, et al. Normative data on the Boston Naming Test and two equivalent 30-item short forms. Clin Neuropsychol. 2000;14:526–534. doi: 10.1076/clin.14.4.526.7204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivnik RJ, Malec JF, Smith GE, Tangalos EG, Petersen RC. Neuropsychological tests’ norms above age 55: COWAT, BNT, MAE token, WRAT-R reading, AMNART, STROOP, TMT, and JLO. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1996;10:262–278. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaton R, Miller S, Taylor M, Grant I. Revised Comprehensive Norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically Adjusted Neuropsychological Norms for African American and Caucasian Adults. Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shirk SD, Mitchell MB, Shaughnessy LW, et al. A web-based normative calculator for the uniform data set (UDS) neuropsychological test battery. Alzheimer’s research & therapy. 2011;3:32. doi: 10.1186/alzrt94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandt JSM, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology. 1988;1:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Wolozin BL, Davies P, Kromer LJ, Damasio AR. Alz-50 antibody recognizes Alzheimer-related neuronal changes. Annals of neurology. 1988;23:371–379. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ihara Y, Abraham C, Selkoe DJ. Antibodies to paired helical filaments in Alzheimer’s disease do not recognize normal brain proteins. Nature. 1983;304:727–730. doi: 10.1038/304727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauckner J, Frey P, Geula C. Comparative distribution of tau phosphorylated at Ser262 in pre-tangles and tangles. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:767–776. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geula C, Mesulam MM, Saroff DM, Wu CK. Relationship between plaques, tangles, and loss of cortical cholinergic fibers in Alzheimer disease. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1998;57:63–75. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199801000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrison TM, Weintraub S, Mesulam MM, Rogalski E. Superior memory and higher cortical volumes in unusually successful cognitive aging. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18:1081–1085. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712000847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allman JM, Tetreault NA, Hakeem AY, et al. The von Economo neurons in frontoinsular and anterior cingulate cortex in great apes and humans. Brain Structure & Function. 2010;214:495–517. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butti C, Santos M, Uppal N, Hof PR. Von Economo neurons: Clinical and evolutionary perspectives. Cortex. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Southard EE. General Aspects of the Brain Anatomy of the Feeble-Minded. Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 1918;14(2):25–58. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raghanti MA, Spurlock LB, Robert Treichler F, et al. An analysis of von Economo neurons in the cerebral cortex of cetaceans, artiodactyls, and perissodactyls. Brain Struct Funct. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0792-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nimchinsky EA, Vogt BA, Morrison JH, Hof PR. Spindle neurons of the human anterior cingulate cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1995;355:27–37. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan RH, Pok K, Wong S, Brooks D, Halliday GM, Kril JJ. The pathogenesis of cingulate atrophy in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:30. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim EJ, Sidhu M, Gaus SE, et al. Selective frontoinsular von Economo neuron and fork cell loss in early behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22:251–259. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santillo AF, Nilsson C, Englund E. von Economo neurones are selectively targeted in frontotemporal dementia. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:572–579. doi: 10.1111/nan.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dijkstra AA, Lin L-C, Nana AL, Gaus SE, Seeley WW. Von Economo Neurons and Fork Cells: A Neurochemical Signature Linked to Monoaminergic Function. Cerebral Cortex. 2016 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cobos I, Seeley WW. Human von Economo Neurons Express Transcription Factors Associated with Layer V Subcerebral Projection Neurons. Cereb Cortex. 2013 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stimpson CD, Tetreault NA, Allman JM, et al. Biochemical specificity of von economo neurons in hominoids. Am J Hum Biol. 2011;23:22–28. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evrard HC, Forro T, Logothetis NK. Von Economo neurons in the anterior insula of the macaque monkey. Neuron. 2012;74:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]