Abstract

Background

Herbal medicine (HM) regulation is less developed than that of allopathic medicines, with some countries lacking specific regulations.

Objective

For the purpose of informing a registration system for HMs in Kuwait, which does not manufacture but imports all HMs, this study compared the similarities and differences between the current HM registration systems of five countries.

Methods

The five countries were selected as major source countries of HM in Kuwait (United Kingdom (UK), Germany and United States of America (USA)) or because of geographical proximity or size and approach (United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kingdom of Bahrain). Documentary analysis of HM classification systems was performed by reviewing the regulatory and law documentation of these countries’ drug regulatory authority websites. Data on HM definition, classification and the main requirements for registration were extracted and analysed for similarities and differences.

Results

There was diversity in the classification of HMs across all five countries including terms used, definitions, type of law, requirements, restrictions and preparation type. The regulatory authorities of the UK, Germany, UAE and Kingdom of Bahrain offer simplified registration for HMs, where plausible efficacy as a result of established traditional use is sufficient. In USA, the concept of traditional use does not exist, instead, the product can be categorised as a dietary supplement where no assessment or evaluation is required prior to marketing.

Conclusions

Owing to the inconsistencies in how drug regulatory authorities define HMs, it will be important to design a clear definition of what constitutes a HM in Kuwait, which is a country that does not produce and register its own products but assesses products registered elsewhere.

Key Points

| To inform the design of a registration system for herbal medicines (HMs) in Kuwait, which does not produce but imports all HMs, the drug regulatory authorities’ approaches to HM regulation were compared in five countries. |

| There was a lack of consistency in the definition of what constitutes an HM, and how these are assessed, reviewed and regulated. |

| Some drug regulatory authorities, USA in particular, do not assess dietary supplements prior to marketing, which has implications for regulatory systems in a country like Kuwait where review currently depends on how a HM is defined and regulated in the source country. |

Introduction

Historically, plants have been used for the treatment and prevention of various illnesses. With the revolution of science, the popularity of herbal medicines (HMs) has widened. It is estimated that 80% of the world’s population use HMs in some capacity within their primary healthcare [1]. With the increasing consumer demand, the HM worldwide market is expected to reach US $107 billion by the end of 2017 [2]. As the global use of HMs continues to grow, public health issues related to their safety are also increasingly recognised. The consumption of some HMs has resulted in serious adverse reactions such as hypersensitivity and organ toxicities [1]. HMs have also been found to modify the pharmacokinetics of some drugs [3]. In the Gulf Region, the highest incidences of HMs were attributed to contamination with toxic substances and the adulteration of HMs with conventional medicines especially in slimming and sexual performance products [4].

Given the increasing consumer demand, the market value and potential toxicity, national health authorities have developed laws to ensure the safe use of HMs. In some national markets, such as Germany, France and Austria, HMs are well defined and the HM registration system is well established under existing laws [5]. However, in other markets, such as Kuwait, adequate regulatory measures for HM registration are lacking, leading to safety concerns [6].

For the purpose of this article, HMs are defined as “Herbal preparations that are manufactured industrially in which the active ingredient(s) is/are purely and naturally original plant substance(s), which is/are not chemically altered and is/are responsible for the overall therapeutic effect of the product”.

Kuwait: A Country without a Herbal Medicine Definition and Classification System

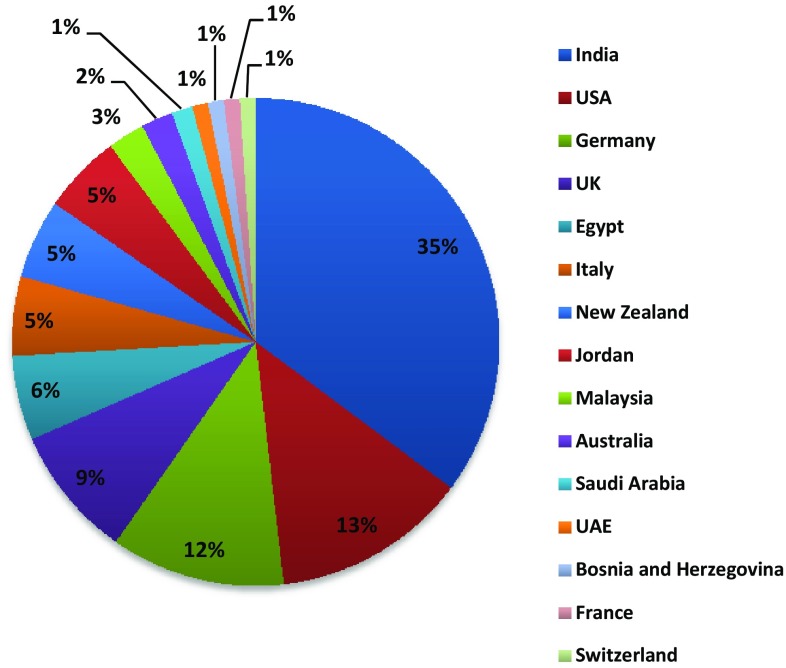

Kuwait is a small wealthy emirate located at the top of the Arabian Gulf between Iraq and Saudi Arabia. The pharmaceutical manufacturing environment in Kuwait is not very competitive because of the country’s small population of 4.4 million (with 30.5% being Kuwaiti) [7]. As a result, all HMs in Kuwait are imported from other countries and registered through the Kuwait Drug and Food Control Administration (KDFCA). The registration departments in the KDFCA consist of five separate registration units: the pharmaceutical unit, herbal unit, veterinary unit, unclassified unit (borderline), cosmetics unit and food supplements unit. The herbal unit registers herbal teas, herbal coffees, homeopathic medicines and HMs. For an HM to be approved into the market, two main steps must be carried out: agent and company registration, and HM registration. Because all HMs in Kuwait are imported from other countries, the first step ‘agent and company registration’ involves the manufacturing company appointing a local agent to represent the product in Kuwait. This process is a one-off procedure required for the registration of all products. Moreover, the company registration requires the submission of an original and legalised Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) certificate and a manufacturing licence from the health authority of the product’s country of origin. In the second step, ‘HM registration’, the agent must submit a sample of the product and a dossier containing documents required for the registration of HMs in accordance with Ministerial Decree 201/9. The dossier must contain an original and legalised Certificate of Pharmaceutical Product or Free Sale Certificate, patient information leaflet, artwork of the finished product outer pack and label, original proposed price certificate authenticated by the Kuwaiti Embassy in the country of origin, toxicological and clinical studies or evidence of acknowledged scientific references, certificate of analysis of finished product and full stability studies. All products under the herbal unit must be analysed in the KDFCA quality control (QC) laboratory prior to their marketing. The QC tests depend on the certificate of analysis of the finished products that the agent provides in the initial submission of the dossier. This certificate is used to compare the specifications on the certificate with the QC analytical results. Currently, there are 191 HMs registered under the herbal unit at the KDFCA. Further relevant products are registered under the unclassified and food supplement units, but there is no clear or current database of these. Kuwait imports the majority of its HMs from India, USA, Germany and the UK (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of imported registered herbal medicines at the herbal unit in the Kuwait Drug and Food Control Administration with countries of origin. UAE United Arab Emirates.

(Source: Kuwait Drug and Food Control Administration Herbal Registration Department)

The regulatory status of HMs varies from one country to another [8]. Depending on certain factors, where a HM may be defined as a functional food or a dietary supplement in one country, it may be defined as a herbal or a conventional medicine in others. This results in HMs imported into Kuwait being registered under different units in the KDFCA, as the allocation is not based on the nature or characteristics of the product itself, but its regulatory status in the country of origin.

Because of the lack of a clear definition of what constitutes an HM and a classification and registration system for HMs in the KDFCA, the registration process is uncoordinated. Consequently, some HMs are registered under the unclassified unit as dietary supplements or as functional food under the food supplements unit, both requiring few and less stringent requirements for registration. These units do not require the submission of safety studies or scientific references and not all products are analysed in the laboratory prior to their marketing. As a result, some products are marketed with poor quality and safety, resulting in safety issues for the public’s health. This is evident in the case of a young Kuwaiti girl who died after consuming registered herbal diet pills, which resulted in a heart attack and liver failure [6]. It is therefore important to establish a clear classification of HMs in the KDFCA structure, to allow a standardised approach for evaluating the safety, efficacy and quality of HMs imported into Kuwait.

In his book ‘Public Policymaking’, Anderson proposes that the policymaking process is a cycle with functional activities consisting of five steps [9]: (1) identify problem, (2) formulate options, (3) state contents of selected option, (4) implement option and (5) evaluate outcome of implemented option. He suggests that the policy steps are a workable approach to the analysis and study of policymaking with a scientific and academic approach. Having identified the problem, namely the absence of a classification and definition for imported HM registration in the KDFCA, for the second step (formulation of options), the authors reviewed relevant literature on policy implementation particularly with regard to HM regulations. However, limited documentation was identified on concepts from existing policies of other countries on how HM classifications were developed and implemented into their drug regulatory authority's (DRA) system. Furthermore, despite World Health Organization efforts in producing international guidelines and consensus on HMs [10–19], countries continue to face difficulties in the implementation of HM regulations, owing to their diversity and complexity [20]. In the context of a wider project to inform a HM registration system in Kuwait, the aim of this article is to investigate the existing laws of DRA classification and definition of HMs in five countries and to illustrate a comparison.

Materials and Methods

Country Choice

Generally, countries were selected for this comparison because they either have established registration processes and are major source countries for HMs imported into Kuwait (Germany, the UK and USA (Fig. 1)) or are countries similar to Kuwait in geographical proximity or size and approach (United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kingdom of Bahrain). In countries within the European Union (EU), in this case Germany and the UK, the regulation of HMs falls within the scope of European Directive 2004/24/EC, which obligates the marketing of each product to be granted, based on rigid legislation for all EU countries. However, the EU directive guides implementation in each country’s own law; therefore, there may be differences in the implementation of Directives [21]. We chose Germany and the UK because of the differences between the two. Germany has a very well-established HM registration system in place that predates EU legislation and approximately 70% of German physicians have confidence in prescribing HMs to their patients [22]. Conversely, the UK introduced a system for HMs relatively recently based on the EU Directive.

In USA, the current pharmaceutical medicine regulatory system is acknowledged internationally as the gold standard for drug safety and efficacy [23]. However, there have been numerous criticisms about the regulation of dietary supplements and whether the regulation of HMs as dietary supplements is sufficient in USA [1, 24, 25]. USA is the major market for the pharmaceutical industry in which approximately 20,000 HMs are available in USA alone [24] with an estimated value of US $62 billion, which the World Health Organization expect will increase to US $5 trillion by 2050 [26].

In UAE and the Kingdom of Bahrain, about 90% of pharmaceutical products are imported from abroad [27]. The regulation of pharmaceuticals in these countries is harmonised in view of their special relationship, geographic proximity, similar political systems based on Islamic beliefs and common objectives, ensuring a joint management of the safety, quality and efficacy of medicines. Therefore, the Kingdom of Bahrain and UAE were included in this country comparison. India has been excluded, despite being the largest source country of HMs imported into Kuwait, as the published literature indicates essential regulatory processes in the Indian HM registration system are found to be lacking, with existing legislation containing loopholes and being weakly implemented [28–30].

Data Collection and Analysis

We used document analysis, which is a systematic form of qualitative analysis requiring official documents to be reviewed and interpreted by the researcher to give meaning to an assessment topic [31]. Official law documents of HM registrations were identified from the five countries’ competent DRA websites: UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency [32, 33]; Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices Germany [34]; US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [35]; Department for Pharmacy and Drug Control UAE [36]; and Bahrain National Health Regulatory Authority [37]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria used for the data search in each regulatory authority website are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for data used in the document analysis

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Available in English or Arabic | Language other than English or Arabic |

| Herbal preparations manufactured industrially in which the active ingredient(s) is/are purely and naturally original plant substance(s), which is/are not chemically altered and is/are responsible for the overall therapeutic effect of the product | Other types of preparations including homeopathic products, cosmetics, medical devices and conventional medicines including conventional medicines containing herbal substance(s) as active substance(s) that has/have been synthesised or chemically altered Herbal products as teas or coffees |

| Herbal preparations used for treating/curing purposes or supporting/improving body functions | Herbal preparations that do not have a therapeutic effect and are used as flavours or additives or have a cosmetic effect |

| Herbal preparations for human use only | Herbal preparations for animal use |

| Herbal preparations in a packed form | Raw unpacked herbs |

| Premarketing registration of herbal products (initial registration) | Renewal of registration, amendments and cancelation of HMs Post-marketing handling and control of HMs |

| HM registration for the consumption of the general public | HMs as parcels for personal use HMs for the purpose of supplying to patients by herbal practitioners following a one-to-one consultation |

HMs herbal medicines

The selection of data started by searching through each country’s DRA website. The illustration of data categories or ‘themes’ could not be separated from the data selection phase. Because our aim was to inform policy design and implementation for a classification and definition for HM registration in Kuwait, the first category of choice was the definition of an “authorised industrially manufactured therapeutic herbal product for registration”, which is associated with the registration pathways in each country’s DRA. The second category was the main technical registration requirements that ensure the product’s safety, quality and efficacy. A subcategory ‘label requirements’ was added, as it is an essential element for marketing a HM in some countries. The third category concerned how HMs are classified in each DRA. This category consists of factors that guide the classification decisions for the registration pathways and requirements in each DRA; the presentation of the product and the purpose for which it is administered.

Data selected were extracted into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, analysed for similarities and differences across the countries within each category, and presented in a comparison table. The terminology used to describe (herbal) medicines in one country is different in another country; therefore, to maintain consistency in the comparison procedure, where appropriate, the authors have described the “authorised industrially manufactured therapeutic herbal product for registration” as “HM”.

Results

Definitions and Pathways

Table 2 summarises the definitions of HMs in each of the investigated country’s DRA. Under each definition, DRAs divide the product into different pathways for registration according to specific laws. All comparative authorities in their definitions state that HMs consist of substances of plant materials. The UK, Germany, UAE and the Kingdom of Bahrain have the highest resemblance in defining HMs, also defining a preparation. The UK and Germany use the term herbal medicine to describe HMs. USA uses the term botanical preparation, the UAE uses the term product derived from plant origin and the Kingdom of Bahrain uses the term herbal product.

Table 2.

Summary comparison of herbal medicine (HM) definition and its regulation pathways in the drug regulatory authority systems of the UK, Germany, USA, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kingdom of Bahrain

| Regulatory authority | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | Germany | USA | UAE | Kingdom of Bahrain | |

| Definition | “A product is an herbal medicine if the active ingredients are herbal substances and/or herbal preparations only” “The herbal substance being processed can be reduced or powdered, a tincture, an extract, an essential oil, an expressed juice or a processed exudate” “A herbal preparation is when herbal substances are put through specific processes which include extraction, distillation, expression, fractionation, purification, concentration and fermentation” |

“Herbal products are medicinal products which exclusively contain as active substances, either one or more herbal substances, one or more herbal preparations, or one or more such herbal substances in combination with one or more such herbal preparations. Herbal substances are all mainly whole, fragmented or cut plants, plant parts, algae, fungi, lichen in an unprocessed, usually dried form, but sometimes fresh” “Herbal substances are precisely defined by the plant part used and the botanical name according to the binomial system” “Herbal preparations are obtained by subjecting herbal substances to treatments such as extraction, distillation, expression, fractionation, purification, concentration or fermentation. These include comminuted or powdered herbal substances, tinctures, extracts, essential oils, expressed juices and processed exudates” |

“Botanical preparations consist of vegetable materials, which include plant materials, algae, macroscopic fungi, or a combination of these materials. Botanical preparations often have unique features, for example, complex mixtures, lack of a distinct active ingredient, and substantial prior human use” “Dietary supplement is a product other than tobacco intended to supplement the diet: a vitamin, a mineral, herbs or other botanical, an amino acid, a dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake, or a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or a combination of any of the aforementioned ingredients” |

“Product derived from plant origin is a finished labelled medicinal product that contains as active ingredients aerial or underground parts of plants, or other plant materials or combinations thereof, where in the crude state or as plant preparations intended for prophylactic or therapeutic or other human health benefits” “Plant preparations are herbal ingredients present in a form other than the crude medicinal plant material including powdered plant material, balsams, dried and fluid extracts, tinctures, essential oils etc., prepared from plant material, and plant preparations obtained by fractionation, purification or concentration, without chemically defined isolated constituents regardless of whether or not its therapeutically active constituents have been identified” |

“Herbal product contains as active substances herbal substances or herbal preparations, alone or in combination” “A herbal substance is whole, fragmented or cut plants, plant parts, algae, fungi, lichen in an unprocessed, usually dried form but sometimes fresh” “A herbal preparation is obtained by subjecting herbal substances to treatments such as extraction, distillation, expression, fractionation, purification, concentration or fermentation. These include comminuted or powdered herbal substances, tinctures, extracts, essential oils, expressed juices and processed exudates” |

| Registration pathways |

THR (traditional use) with directive 2004/24/EC or MA (conventional) with directive 2001/83/EC |

THR (traditional use) with directive 2004/24/EC or MA (conventional) with directive 2001/83/EC |

Dietary supplement with DSHEA of 1994 (does not get registered) or Botanical drug with Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act |

THM (traditional use)

or HM with Ministerial decree No. 3276/1997 for registration and re-registration of products derived from natural source |

Health product (traditional use) with decree amendments by law No. (20) of 2015 or Medicine with vegetable substance with decree by law No. (18) of 1997 |

DSHEA Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act, MA marketing authorisation, THM traditional herbal medicine, THR traditional herbal registration

Each of the authorities analysed divided HMs into one of two registration pathways. Registration pathways in the UK and Germany are traditional herbal registration (THR) or marketing authorisation (MA); in USA, dietary supplement or botanical drug; in UAE, traditional herbal medicine (THM) or herbal medicine; and in the Kingdom of Bahrain, health product or medicine.

In the UK, Germany, UAE and the Kingdom of Bahrain, the registration pathways offer a simplified registration for HMs, where instead of full registration as a medicine (i.e. requiring an MA and proven clinical efficacy), plausible efficacy as a result of established traditional use is sufficient (simplified registration); THR in the UK and Germany; THM in the UAE and health product in the Kingdom of Bahrain. A manufacturer can still register a medicine containing only herbal ingredients as any other allopathic medicine, which means stricter requirements with regard to evidence of efficacy (strict registration); MA in UK and Germany, registration of HM in the UAE and the registration of a medicine with a vegetable substance in the Kingdom of Bahrain. USA differs from the other comparative authorities in that the traditional use pathway does not exist, instead, the product can be categorised under the dietary supplement pathway where products do not get assessed or registered prior to their marketing, which is in accordance with the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. The second pathway in USA involves registering the HM as a botanical drug (strict registration), which requires scientific evaluation and review by the authority prior to marketing.

Main Registration Requirements

Table 3 summarises the main registration requirements for assessing HMs in each of the investigated country’s DRA. Under all registration pathways included in this study, apart from the dietary supplement pathway in USA, the authorities require the submission of evidence of GMP and QC tests for quality, bibliographic data or toxicological tests for safety, and evidence of traditional use or clinical studies for efficacy. In the dietary supplement pathway in the USA regulatory authority, products do not require registration; however, if it is a dietary supplement that contains a new dietary ingredient (NDI), the manufacturer must notify the authority and the notification must include evidence that the NDI is safe. An NDI means a dietary ingredient that was not marketed in USA as a dietary supplement before 15 October, 1994. All dietary supplements sold before 1994 were considered safe and could remain on the market without the need to file an NDI notification. The manufacturer may choose to market the dietary supplement even if the FDA indicated that the NDI notification was unsatisfactory. Although dietary supplements do not undergo assessment or registration, the FDA compels that a disclaimer must be added to the products showing that the FDA has not evaluated the product, the product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease and it should clearly state that it is a dietary supplement.

Table 3.

Summary comparison of herbal medicine (HM) main registration requirements in the drug regulatory authority systems of the UK, Germany, USA, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kingdom of Bahrain

| Main registration requirements | Regulatory authority | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | Germany | USA | UAE | Kingdom of Bahrain | |

| Evidence of quality | GMP standards and QC tests for THR and MA | GMP standards and QC tests for THR and MA | Not required for dietary supplements GMP standards and QC tests for botanical drugs |

GMP standards and QC tests for traditional HMs and HMs Declaration of pork-free contents Declaration of alcohol content |

GMP standards and QC tests for health products and medicines with a vegetable substance Declaration of pork-free contents Declaration of alcohol content |

| Evidence of safety | Bibliographic data for THR Toxicological tests for MA |

Bibliographic data for THR Toxicological tests for MA |

Not required for dietary supplements unless it is a NDI Toxicological tests for botanical drugs |

Bibliographic data for traditional HMs Toxicological studies for HMs |

Bibliographic data for health products Toxicological studies for medicines with a vegetable substance |

| Evidence of efficacy | Long tradition of use for at least 30 years (including 15 years in the EU) for THR Clinical studies for MA |

Long tradition of use for at least 30 years (including 15 years in the EU) for THR Clinical studies for MA |

Not required for dietary supplements Clinical studies for botanical drugs |

Copies of at least two traditional HMs for each herbal ingredient for traditional HMs Clinical studies for HMs |

Copies of published scientific literature or international monographs for health products Clinical studies for medicines with a vegetable substance |

| Label requirement | For THR: must include a statement that the product is exclusively based on long-standing use Must include a certification mark (THR) |

For THR: must include the words “traditional medicines” and “traditionally used” | For dietary supplements: must include a disclaimer: “This statement has not been evaluated by the FDA. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease” Must state on the label that it is a dietary supplement |

No requirements | No requirements |

EU European Union, FDA US Food and Drug Administration, GMP Good Manufacturing Practice, MA marketing authorisation, NDI new dietary ingredients, QC quality control, THR traditional herbal registration

In the UK and Germany, as part of the EU harmonisation under Directive 2004/24/EC, the THR (simplified) pathway was established to create a simplified registration procedure for all traditional HMs not fulfilling the requirements for the MA (strict) pathway under Directive 2001/83/EC. Directive 2004/24/EC substitutes the requirement for medicines to have undergone randomised controlled trials with a clause of traditional use that includes evidence of 30 years of safe use; at least 15 years of which must be within the EU, to demonstrate plausible efficacy. Directive 2001/83/EC is still in use and the simplified procedure should be used only where no MA can be obtained. The regulatory authorities in those countries also require that the manufacturing company must include a statement and/or a mark clearly showing that the product is traditionally used. Similarly, in the UAE and the Kingdom of Bahrain, submission of copies of bibliographic published scientific references for traditional use is sufficient for proving the product’s safety and efficacy and accordingly the product would be eligible for the simplified registration pathway. In addition, being Islamic countries, both countries have passed similar laws requiring that medicines including herbals must be free from any pork materials, and if a product contains any alcohol, a declaration of alcohol percentage must be submitted along with specifying the reason.

Classifications

For a HM to be assessed and evaluated under the appropriate registration pathway, HMs in the study authorities are classified according to two key features or characteristics; the presentation of the product and the purpose for which it is administered (Table 4). In all the comparative authorities, the medical claims and the preparation type affect the product classification under the two registration pathways in each regulatory authority. The strictest registration pathway is applied to products with medical claims of curing and treating diseases.

Table 4.

Summary comparison of herbal medicine (HM) classification factors under the different pathways in the drug regulatory authority systems of the UK, Germany, USA, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kingdom of Bahrain

| Classification factors | Regulatory authority | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | Germany | USA | UAE | Kingdom of Bahrain | |

| Presentation | If a claim to treat major health conditions is added, the product is classified as a medicine that requires MA If a therapeutic indication based on long-standing use is added, the product is classified as a medicine that requires THR THR products can only be presented as oral, external and inhalation preparations MA products may include any preparation type |

If a claim to treat major health conditions is added, the product is classified as a medicine that requires MA If a therapeutic indication based on long-standing use is added, the product is classified as a medicine that requires THR THR products can only be presented as oral, external and inhalation preparations MA products may include any preparation type |

For a product to be classified as a dietary supplement, only function and structure claims are allowed Products that include claims of treating, diagnosing, preventing or curing diseases are automatically classified as botanical drugs Dietary supplements are only allowed in oral preparations Botanical drugs can be presented in any preparation |

Products that include medical claims are classified as HMs If a product uses traditional use claims, it is classified as a traditional HM Traditional HMs can be presented in an oral, topical and rectal formulations Only HMs can be presented in any preparation |

Products that contain claims based on traditional use are classified as health products If a medical claim to cure, treat or prevent a disease is added on the label, the product is classified as a medicine with a vegetable substance Health products can only be presented as oral, topical and nasal formulations Medicines with a vegetable substance can be presented in any preparation |

| Purpose | If a product requires the supervision of a medical practitioner, or a medical prescription, the product is classified as a medicine that requires MA | If a product requires the supervision of a medical practitioner, or a medical prescription, the product is classified as a medicine that requires MA | Not specified | Not specified | Products that contain a substance that is supplied on a medical prescription is classified as a medicine with a vegetable substance |

MA marketing authorisation, THR traditional herbal registration

In the USA regulatory authority, dietary supplements are only allowed in oral preparations, all other preparation types are classified under botanical drugs, which require the strictest registration requirements. In comparison, the UK, Germany, UAE and the Kingdom of Bahrain regulatory authorities, the traditional (simplified) registration pathway may include other preparations that can be administered externally but not by injection. In the UK, Germany and the Kingdom of Bahrain regulatory authorities, if the herbal product requires a medical prescription or practitioner, the product is automatically classified in the pathway that requires the most strict registration requirements; i.e. requiring MA.

Discussion

This study compared the similarities and differences between the current HM registration systems of five countries, indicating diversity in the classification of HMs including terms used, definitions, type of licence, requirements, restrictions and preparation type. Comparing the five countries, the UK, Germany, UAE and the Kingdom of Bahrain have applied a reasoned and more structured approach to registering HMs. USA differs from these four countries in two important aspects.

First, the marketing of HMs. The regulation of HMs in USA differs considerably from that in UK, Germany, UAE and the Kingdom of Bahrain. In USA, when HMs are regulated under the dietary supplements pathway, along with vitamins, minerals and other nutritionals, they do not undergo pre-marketing safety evaluation by the FDA. Conversely, HMs marketed in the UK, Germany, UAE and the Kingdom of Bahrain must adhere to pre-marketing HM registration laws and registration requirements including specific laboratory, manufacturing and storage standards. The FDA’s intervention with dietary supplements does not begin unless the product enters the market and is proven to have a significant risk to the consumer. A study conducted by the National Institutes of Health found that 15.5% of US hepatotoxic events were associated with the consumption of dietary supplements and herbal products [38]. In another study conducted in 2013 by researchers in Toronto who analysed 44 herbal supplements sold in both USA and Canada, it was revealed that less than half the supplements contained any herbal substances mentioned on the label and more than half the analysed supplements contained additional ingredients that were not on the label [39]. The assessment of safety has therefore become more challenging in USA as a result of the type of regulation used [40]. While regulating HMs as dietary supplements increases the availability and variety of many products for the consumer, the lack of registration and assessment of such products can be a major disadvantage for consumer safety.

Second, registration requirements for HMs. In USA, if a claim to treat or cure a disease is added to the label of a dietary supplement, the product will be regarded as a drug and require assessing and registering prior to marketing. This classifies the product under the botanical drug pathway and the same rigorous requirements and standards of conventional drugs apply, including the evidence of clinical studies. As a result, the FDA received over 400 botanical drug applications between 2004 and 2013, in which only two have so far received the FDA approval [41]. On the contrary, the UK, Germany, UAE and the Kingdom of Bahrain established simpler registration requirements based on traditional use as evidence of efficacy existing. This ensures that the efficacy of traditional herbal medicinal products is considered plausible without the need for conducting extensive clinical studies. In Germany and the UK, as per the regulatory harmonisation of EU member states under the latest Directive 2004/24/EC, HMs registered by one member state shall be accepted automatically by other member states. The new policy provides public health benefits to those countries that did not have such legislation previously. The directive obligates that the members’ health authorities must also perform a premarketing product quality and safety check. Therefore, this legislation may reduce the risk that unsafe HMs will enter the market [42].

Overall, because HMs imported into Kuwait are registered according to the product’s status in the country of origin, a major challenge is the inconsistency in the definition of a HM across the international DRAs. This explicates the uncoordinated registration process in the Kuwaiti DRA, which results in some unevaluated products, for example, imported dietary supplements from USA, being registered under units with insufficient evaluation measures.

A reasonable anticipated step would be the possibility for all international DRAs including Kuwait to adopt a universal harmonised definition of what constitutes a HM for the purpose of registration that would guide the product into the most appropriate conformity assessment. A proposed definition could be: herbal preparations made from one or more herbs as the active ingredients, which may additionally contain excipients; however, finished products to which the active substance has been chemically altered or added, including synthetic compounds and/or isolated constituents from herbal material, are not considered herbal [43]. Such a clear definition would also allow a standardised regulation, which could ensure that all HMs approved for sale are safe on a global scale, especially with USA being one of the world’s largest exporters for HMs. In Kuwait, in addition to adopting a universal definition for HMs, a directive should also be specified that all products that match the proposed definition must be assessed under one department (the herbal unit). This is to prevent HMs from being categorised as dietary supplements, which as a result circumvent the detailed assessment procedure of the KDFCA. Moreover, in the process of improving HM legislation, the KDFCA will need to consider carefully how to regulate products imported from countries where regulations are very loose or do not exist.

This study has some limitations, the main one being the decision of disqualifying India despite their existing HM regulations, which has led us to neglect a major source country for HMs in Kuwait. However, this study focused on gaining insights of international, well-established, competent health regulatory systems to inform a robust HM registration system in Kuwait, and evidence indicating the absence of essential regulatory processes in the Indian HM registration system and weak implementation of the current legislation [26–28] required the exclusion of India as a competent DRA. Another limitation is that the findings of the study were limited to the information available on each country’s DRA website. Therefore, to be consistent, it has only been possible to analyse and compare the data available in all DRAs together and was not always possible to compare all countries across other aspects that may not be publicly available. For example, guidelines or standard operating procedures for the classification of HMs. Despite the limitations, the study provided an international classification reference and recommends a definition for HM registration for Kuwait and other countries that do not currently have such laws implemented.

Conclusion

Some jurisdictions allow an additional less stringent registration process for HMs, which permits efficacy to be plausible as a result of traditional use, while others, USA in particular, do not. Consequently, many such products escape sufficiently rigorous review as they are instead marketed as dietary supplements. This needs to be considered in designing or updating registration systems in countries such as Kuwait, which import such products and assess these in the light of their regulatory status in their country of origin. Because of the heterogeneity in other countries’ definitions, it will be essential for Kuwait to clearly define what constitutes a HM and require that all relevant products be reviewed in one unit to prevent any being misinterpreted as dietary supplements.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

The study was undertaken as part of a PhD, which is fully funded by the Kuwaiti Ministry of Health. Open Access was funded through an institutional agreement with Springer Nature.

Conflict of interest

Azhar H. Alostad, Douglas T. Steinke and Ellen I. Schafheutle have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this study.

References

- 1.Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol. 2014;4:177. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nirali J, Shankar M. Global market analysis of herbal drug formulations. Int J Ayu Pharm Chem. 2016;4(1):59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreira DDL, Teixeira SS, Monteiro MHD, De-Oliveira ACA, Paumgartten FJ. Traditional use and safety of herbal medicines. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2014;24(2):248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bjp.2014.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fahmy SA, Abdu S, Abuelkhair M. Pharmacists’ attitude, perceptions and knowledge towards the use of herbal products in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2010;8(2):109–115. doi: 10.4321/S1886-36552010000200005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan T-P, Deal G, Koo H-L, Rees D, Sun H, Chen S, Shikov AN. Future development of global regulations of Chinese herbal products. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140(3):568–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Enzi M. Woman dies after consuming unidentified slimming pills. Kuwait: Times; 2015. p. 148b. [Google Scholar]

- 7.PACI. Public Authority of Civil Information (PACI): population statistics. 2017. http://www.paci.gov.kw/stat/default.aspx. Accessed 21 Jul 2017.

- 8.World Health Organization. Legal status of traditional medicine and complementary/alternative medicine: a worldwide review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/h2943e/h2943e.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr 2017.

- 9.Anderson JE. Public policymaking. Stamford (CT): Cengage Learning; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. WHO traditional medicines strategy 2014–2023. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/92455/1/9789241506090_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 28 Apr 2017.

- 11.World Health Organization. Quality control methods for herbal materials. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/h1791e/h1791e.pdf. Accessed 5 Oct 2017.

- 12.World Health Organization. Benchmarks for training in traditional Chinese medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s17556en/s17556en.pdf. Accessed 2 Sept 2016.

- 13.World Health Organization. Guidelines for assessing quality of herbal medicines with reference to contaminants and residues. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s14878e/s14878e.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr 2017.

- 14.World Health Organization. The world medicines situation. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s6160e/s6160e.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr 2017.

- 15.World Health Organization. WHO traditional medicine strategy 2002–2005. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2002. http://www.wpro.who.int/health_technology/book_who_traditional_medicine_strategy_2002_2005.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr 2017.

- 16.World Health Organization. Report of the inter-regional workshop on intellectual property rights in the context of traditional medicine. Bangkok: World Health Organization. 2000. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/66788/1/WHO_EDM_TRM_2001.1.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr 2017.

- 17.World Health Organization. Regulatory situation of herbal medicine, worldwide review. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1998. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/whozip57e/whozip57e.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2017.

- 18.World Health Organization. Traditional practitioners as primary health care workers. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1995. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/h2941e/h2941e.pdf. Accessed 2 Sept 2016.

- 19.World Health Organization. Traditional medicine and health care coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1988. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js7146e/. Accessed 2 Sept 2016.

- 20.Bhat SG. Challenges in the regulation of traditional medicine: a review of global scenario. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2015;3(6):110–120. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiesener S, Falkenberg T, Hegyi G, Hök J, di Sarsina PR, Fønnebø V. Legal status and regulation of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe. Forsch Komplementmed. 2012;19(Suppl. 2):29–36. doi: 10.1159/000343125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joos S, Glassen K, Musselmann B. Herbal medicine in primary healthcare in Germany: the patient’s perspective. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:294638. doi: 10.1155/2012/294638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handoo S, Arora V, Khera D, Nandi PK, Sahu SK. A comprehensive study on regulatory requirements for development and filing of generic drugs globally. Int J Pharm Investig. 2012;2(3):99. doi: 10.4103/2230-973X.104392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bent S. Herbal medicine in the United States: review of efficacy, safety, and regulation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):854–859. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0632-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro VJ, Barnhart H, Bonkovsky HL, Davern T, Fontana RJ, Grant L, Sherker AH. Liver injury from herbals and dietary supplements in the US Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology. 2014;60(4):1399–1408. doi: 10.1002/hep.27317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ajazuddin SS. Legal regulations of complementary and alternative medicines in different countries. Pharmacogn Rev. 2012;6(12):154. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.99950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandra K, Prabahar A, Rao N. A breif analysis of regulatory structure and approval process of pharmaceuticals in GCC. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;4(7):1596–1611. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parveen A, Parveen B, Parveen R, Ahmad S. Challenges and guidelines for clinical trial of herbal drugs. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(4):329. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.168035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahoo N, Manchikanti P. Herbal drug regulation and commercialization: an Indian industry perspective. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(12):957–963. doi: 10.1089/acm.2012.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sen S, Chakraborty R, De B. Challenges and opportunities in the advancement of herbal medicine: India’s position and role in a global context. J Herb Med. 2011;1(3):67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2011.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res. 2009;9(2):27–40. doi: 10.3316/QRJ0902027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Traditional herbal medicines: registration form and guidance, herbal and homeopathic medicines and patient safety. 2014. http://www.gov.uk/guidance/apply-for-a-traditional-herbal-registration-thr. Accessed 2 Aug 2017.

- 33.Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. A guide to what is a medicinal product. 2007. http://www.dweckdata.com/PIP/Guidance_note_8_MHRA_June_2007.pdf. Accessed 13 Jul 2017.

- 34.Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. Complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) and traditional medicinal products (TMP). 2013. http://www.bfarm.de/EN/Drugs/licensing/zulassungsarten/pts/_node.html;jsessionid=7FD01B5F05CB6E9253E5953F70860A11.1_cid332. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 35.US Food and Drug Administration. US Food and Drug Administration 101: dietary supplements. 2015. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm050803.htm. Accessed 10 Mar 2017.

- 36.Ministry of Health. United Arab Emirates Ministry of Health, Department of Pharmacy and Drug Control: rules and requirements for registration and re-registration of products derived from natural source. 1997. http://www.moh.gov.ae/en/OpenData/Pages/CPDData.aspx. Accessed 4 Mar 2017.

- 37.National Health Regulatory Authority. Pharmaceutical product classification guideline: Kingdom of Bahrain. 2013. http://www.nhra.bh/SitePages/View.aspx?PageId=43. Accessed 5 Feb 2017.

- 38.Fontana RJ, Watkins PB, Bonkovsky HL, Chalasani N, Davern T, Serrano J, Group DS Drug-induced liver injury network (DILIN) prospective study. Drug Saf. 2009;32(1):55–68. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932010-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newmaster SG, Grguric M, Shanmughanandhan D, Ramalingam S, Ragupathy S. DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):222. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Ventola CL. Current issues regarding complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the United States: Part 1: the widespread use of CAM and the need for better-informed health care professionals to provide patient counseling. Pharm Ther. 2010;35(8):461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Avigan M, Mozersky R, Seeff L. Scientific and Regulatory Perspectives in Herbal and Dietary Supplement Associated Hepatotoxicity in the United States. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(3):331. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Smet PA. Herbal medicine in Europe: relaxing regulatory standards. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(12):1176–1178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization. General guidelines for methodologies on research and evaluation of traditional medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/66783/1/WHO_EDM_TRM_2000.1.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2016.