Abstract

Background:

Palliative care programs are rapidly evolving for patients with life-threatening illnesses. Increased and earlier access for facilities is a subject of growing importance in health services, policy, and research.

Aim:

This study was conducted to explain stakeholders’ perceptions of the factors affecting the design of such a palliative care system and its policy analysis.

Methodology:

Semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted following purposive sampling of the participants. Twenty-two participants were included in the study. The interviews were analyzed using qualitative-directed content analysis based on "policy analysis triangle" framework.

Results:

The findings showed the impact of four categories, namely context (political, social, and structural feasibility), content (target setting), process (attracting stakeholder participation, the standardization of care, and education management), and actors (the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, health-care providers, and volunteers) in the analysis of the palliative care policies of Iran.

Conclusion:

In the past 6 years, attention to palliative care has increased significantly as a result of the National Cancer Research Network with the support of the Ministry of Health. The success of health system plan requires great attention to its aspects of social, political, and executive feasibility. Careful management by policymakers of different stakeholders is vital to ensure support for any national plan, but this is challenging to achieve.

Keywords: Cancer, health policy, palliative care, policymaking

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the third leading cause of death in Iran,[1] and Cancer statistics indicate the registration of 90,000 new cases in the country every year.[2] Considering cancer patients’ need for specialized supportive care, pain management, and symptom control, one of the main requirements of the health systems of all countries is to provide palliative care services to cancer patients.[3] The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended all countries to give priority to this type of care in their public health programs. The lack of access to these services in a community is synonymous with neglecting human rights.[4] This type of care is relatively new in Iran and is provided in a sporadic manner, and the number of service-providing centers is very low in proportion to the entire population.[5] Given the prioritization of palliative care services at various levels by the WHO, Iran's Ministry of Health has recently been designing a palliative care system by prioritizing national cancer control programs, establishing a palliative care workgroup, and using extensive resources and the views of experts.[6] Designing a plan for providing these services as part of the health system necessitates attention to the way people in need of these services can access them, the required workforce and funding, the role and position of health-care centers and personnel, the role of information technology, and the impact of social, ethical, and cultural issues.[7] Every country has different views on palliative care as part of its health system.[8] The first step for health-care policymaking, therefore, seems to be to explain the stakeholders’ perceptions in the context of the country's health-care system. At the same time, common principles hold in the programs, or at the very least, there are many common dimensions that influence policymaking, and the use of the existing models can play an important role in identifying these common dimensions.

Conceptual framework

The Walt and Gilson policy analysis framework 1994, presented for analyzing the health policymaking process in developing countries, addresses four dimensions that make up the totality of a policy, namely context, content, process, and actors.[9] This model offers a method of problem analysis and finding ways to deal with the problem and can be used to analyze how a set of policies, organizations, and social values affect an issue.[10] It answers the question of what political, economic, social, and cultural factors affect health policymaking at the national level.[11] This framework is especially designed for policy analysis in the health sector and analyzes the four aforementioned dimensions together.[12] This model is a simple approach to intersectoral communication in the health sector and emphasizes that these four factors interact with each other. For instance, the "actors" dimension is influenced by the context in which people live and work; "context" is affected by the various political, economic, and social factors at play; the "process" of policymaking is affected by the "actors;" and the "content" of policy refers to the general objective of the policy or a set of specific objectives and actions planned to achieve the goal. Since one of the concerns of policymakers in the current health system of Iran is to design a palliative care system, the present study was conducted to explain stakeholders’ perceptions of the factors affecting the design of such a palliative care system and its policy analysis.

METHODOLOGY

This qualitative research was conducted from August 2016 to February 2017 using the content analysis method. The participants included 22 stakeholders, including cancer patients, caregivers, health-care providers, experts, and policymakers, who were selected using purposive sampling. The patients included in the study had received a definitive diagnosis of cancer by a specialist and at least 6 months had passed since their diagnosis and were undergoing treatment or were in the follow-up stage of their treatment. The studied caregivers had been directly involved in taking care of a cancer patient for more than 6 months. The studied health-care providers included nurses, physicians, social workers, and psychologists, with more than 1 year of experience in working with cancer patients. Cancer experts and policymakers were also among the participants of this study. The present research was carried out at the oncology departments and clinics affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences as the main referral centers in the country. Data were collected through semi-structured in-depth interviews. The interviews were held at a quiet place preferably of participants’ choice with prior arrangements and continued until data saturation occurred.

The interviews were designed differently for the patients, care providers, and policymakers. Before beginning the interviews, the participants were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire and sign an informed consent form; permission to record their voices and take notes was also obtained from them and they were ensured of the confidentiality of their data and their anonymity in the publication of the results and also of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage they wished. The interviews began with a general open-ended question such as "Please talk about when you first learned about your disease. What training needs did you have then?" (question for the patients), "What were your training needs for providing care to the patients?" (question for the care providers), and "What are the training needs of a care system developed for patients?" (question for the policymakers). The interviews were recorded and then transcribed verbatim to ensure that participants’ entire words were preserved. The text of the interviews was first read to gain a comprehensive understanding of its content, and meaning units and initial codes were then determined.[13] The initial codes were categorized and analyzed based on the Walt and Gilson (1994) health policy analysis framework.[9] To ensure the reliability of this study, Guba and Lincoln's four criteria were used.[14] The ethics approval for the research was obtained from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences under the code IR. SBMU. RAM. REC.1395.70.

RESULTS

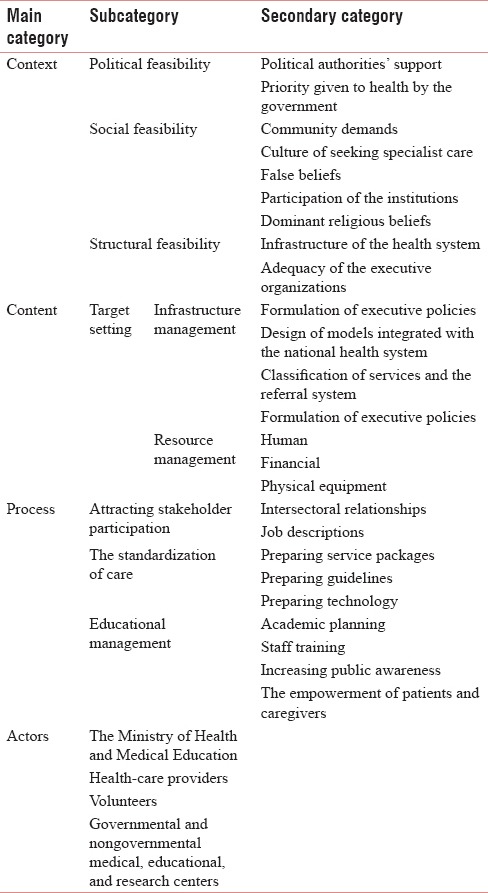

Twenty-two participants were interviewed in this study, including seven cancer patients, two caregivers, six health-care providers, and seven policymakers. A total of 546 codes were extracted from the analysis of the interviews. After removing the repeated codes and merging the similar codes based on the health policy analysis framework, the codes were categorized into four main categories, namely context, content, process, and actors, and 11 subcategories and 25 secondary categories were also formed [Table 1].

Table 1.

Main categories, subcategories, and secondary categories

Context

The main category of "context" includes political, social, and cultural factors that were classified into three secondary categories, namely political feasibility, social feasibility, and structural feasibility.

Political feasibility

The health sector has an important role in the main policies set by governments. Political authorities’ support and the priority given to health by the government were extracted as the subcategories of this secondary category. The participants noted that the support of political authorities and health-care and health education administrators from scientific and academic centers in different educational and research fields related to cancer leads to the production of new science. They also believed that the health sector should be the priority in the government's macro plans and decisions. One of the physicians believed that, " In this government, health is one of the country's top priorities, and the Health Sector Evolution Plan seeks to reduce the out-of-pocket costs of treatment, improve the access to services, and develop the health infrastructures."

Social feasibility

According to the participants, social factors are one of the determinants of health policies and their subcategories include community demands, the culture of seeking specialist care, false beliefs, the participation of the institutions, and the dominant religious beliefs. In this study, attention to health services was considered a public demand by the participants. Moreover, the participants pointed to the unreasonable behaviors of the general public about the use of some services, which can affect palliative care programs, including family physicians and the referral system. "People think that they should visit a specialist as soon as they develop a problem, although our media is also responsible for this. In most television shows about health issues, they tell people to visit a specialist when they have this or that ailment" (a physician).

The spiritual and religious approach in dealing with diseases was noted by the participants as an underlying factor affecting palliative care systems. "When I accepted my illness, I knew my greatest reliance was on God, and I poured my heart out for Him and said "You have redeemed me with this illness and made me pure" (a patient).

The lack of familiarity in the public with the concept of palliative care and the stigma of cancer were also considered an underlying factor affecting the design of such a care system. The stakeholders argued that facilitating state, nongovernmental organization, and public participation in the provision of these care services could be an effective social factor.

Structural feasibility

The participants considered the Ministry of Health's structure an effective factor involved in the design of a care system. This subcategory includes the infrastructure of the health system and the adequacy of the executive organizations, which refer to the available resources and facilities and the role of the executive units (in particular, universities and their affiliated centers) as the first centers for providing health-care services. "According to the health sector evolution plan, hospitals are obliged to procure all the medications and equipment they need for their patients themselves, and insurers are committed to reducing people's share of the costs paid, which means that we have a good potential for providing services" (a physician).

Content

This main category is comprised of a set of objectives and actions planned to achieve the general objective and includes the secondary category of target setting and the two subcategories of infrastructure management and resources.

Target setting

From the perspective of the participants, the design of a care system requires attention to various infrastructures, including the formulation of executive policies, the design of models integrated with the national health system, and the classification of services and the referral system (infrastructure management). The participants noted the importance of transparency in organizational policies. "At the macro level, certain policies and goals are designed with respect to international norms, but executive policies are also needed with specific goals and practical executive mechanisms; planning should be carried out on all three levels – the macro, meso, and micro" (policymaker).

The stakeholders proposed integrating the services of the palliative and supportive care system with the health system as one of the most important goals. Considering that the health-care system is organized to provide justice and access to services for all people at the first, second, and third levels, the participants also noted the importance of the classification of services and the access of those in need of more specialized services through a referral system predicted in policymaking.

One of the most important goals in designing a care system is to consider resources in three categories, namely human resources, financial resources, and physical equipment (resource management). The most important challenges of a palliative care system in this category, as discussed by the stakeholders, include the required size, composition and skills of the workforce, the special attention to reducing patients’ out-of-pocket costs and the attention of policymakers to the share of insurance companies, and providing the needed physical space for the care recipients. An insurance policymaker said, "For patients with cancer, what's happening is that the person himself/herself should not be the one taking care of himself/herself; a system has to be designed for them regardless, and the most appropriate way to do it is through insurance; other ways won’t work."

Process

This category consists of the secondary categories of attracting stakeholder participation, the standardization of care, and educational strategies.

Attracting stakeholder participation

In this study, the participants argued that stakeholder participation is a significant help in the identification of the needs of the care system. The most important components of this subcategory are intersectoral relationships and job descriptions, which refer to the existence of various paths for coordinating the activities and programs of the care system and the clarity of everybody's performance.

The standardization of care

The participants discussed the promotion of standard measures, clinical guidelines, and updated services, which can be classified into three subcategories, namely preparing service packages, guidelines, and technology. Due to the types and complexity of cancer, patients need different service packages. These packages can include instructions on how to provide services at different service points and for different types of cancer and can also define different insurance tariffs for different patients. At the same time, the participants believed that there has to be a valid system of scientific evidence in clinical encounters with the patients. Moreover, the remarkable advances in information technology in the world have led to the idea of using these services for improving care services.

Educational management

The participants proposed educational management as an effective factor in the policymaking process of a palliative care system that can be divided into four subcategories, including academic planning, staff training, increasing public awareness, and the empowerment of patients and caregivers.

The interviewed stakeholders noted the importance of a specific palliative care curriculum and an educational content appropriate to cancer-related disciplines and research as the academic needs of the palliative care system. Among the issues raised by the stakeholders is the design and development of a postgraduate course in palliative medicine as an effective intervention in the field of education: "A palliative medicine fellowship program has been designed by the educational planning commission of the Ministry of Health's medical education secretariat to raise physicians’ knowledge in this area" (a physician).

The continuous and multidisciplinary training of human resources to create and strengthen the various required skills is a major need in the field of education, and multiprofessional team management was most emphasized by the participants.

In this study, public awareness and the necessity of attracting the public attention to the sources of information were considered by the stakeholders as part of the subcategory of increasing public awareness. The participants emphasized the importance of increasing public awareness about advanced types of care, the public's willingness to access valid information resources, and the need to change the society's attitude toward refractory diseases such as cancer.

The findings of the study showed that patient and caregiver training has mostly led to the empowerment of the patients and caregivers and is most effective in their own view when it continues from the time of the patient's admission to the time of discharge and later on: "When the training given is continuous and the follow-ups are ongoing, our confidence in the care received and the process of recovery also increases" (a patient). Regarding the importance of home care and the care needs of cancer patients and their families, the willingness of this group to receive home care creates a good opportunity for empowering the patients and their families.

Actors

Actors, defined both inside and outside the government, have an important role in policy implementation and include the following secondary categories in this study:

Ministry of Health and Medical Education

In the national health system of Iran, of all the top-level actors, the Ministry of Health is in charge of designing the palliative care system and is held responsible for it on behalf of the government. "In our country, the Ministry of Health is the policymaking entity and medical science universities are its executive entities. Universities are expected to have a great influence on the design of this system, including education, support, and even program monitoring" (a faculty member).

Health-care service staff

Palliative care is provided within an interdisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, social workers, psychologists, nutritionists, and rehabilitation specialists. Physicians and nurses are key members of the palliative care team. A policymaker said "The complex nature of cancer necessitates a comprehensive team for providing care. A nurse is the head of this care team, and they have trained a specialist nurse for each disease in advanced countries who serves as the link between the care team and the treatment team."

In a palliative care system, physicians are one of the main pillars of care provision. A policymaker said, "In particular, the presence of general practitioners (GPs) and family physicians at the first level of care provision reduces unnecessary care and hospitalization and also facilitates the access to health-care services."

Volunteers

Volunteer groups and community-based philanthropic organizations perform effective actions since their motivations to support patients are personal.

Governmental and nongovernmental medical, educational, and research centers

Policymakers and care providers have noted the importance of strengthening universities and their affiliated centers to train an expert workforce and multidisciplinary teams.

DISCUSSION

Palliative care is currently one of the challenges of the health system in Iran and its establishment as one of the goals of the health system requires the identification of its effective factors. This study was, therefore, conducted to analyze the factors affecting palliative care policymaking in Iran. The findings showed the impact of four categories, namely context (political, social, and structural feasibility), content (target setting), process (attracting stakeholder participation, the standardization of care, and education management), and actors (the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, health-care providers, and volunteers) in the analysis of the palliative care policies of Iran.

Regarding context, the support of responsible entities, such as the government's prioritization of health, the health infrastructures, and the presence of executive agencies in the country play an important role in the development of a care system. Based on success stories from other countries regarding the establishment of a palliative care system, national macro policies have played a key role in the systematic provision of care services,[15] and "the design of a palliative care package for cancer patients in Iran" has begun since 2011 in the National Cancer Committee with the support of the Cancer Department of the Ministry of Health and is still in progress.[16] In addition to the public attention to health services, the present study found that some people believe that this approach is merely associated with end-of-life services. Other studies have also discussed the improper perceptions of health-care workers[17,18] and the misconceptions of patients and their families about palliative care.[19] Although public attitudes toward palliative and end-of-life care are complex and vague,[20] changing people's attitudes toward these services is one of the key factors underlying the achievement of palliative care goals.[21]

The growing culture of seeking specialist care in the field of health and people's referral to specialists before the diagnosis of the disease leads to the imposition of additional costs and the patient's confusion; in most parts of the world, GPs or clinical nurse specialists are the key providers of palliative care.[22] Overcoming this challenge, as stressed by the participants, can play a significant role in designing a proper care system by encouraging the participation of private and public institutions in raising public awareness about these services and their means of access and also by training GPs and nurses who can provide these services.[23,24] Spirituality can therefore affect the quality of patient care by affecting the caregivers’ health.[25] Considering that 98% of Iranians are Muslim, spirituality is considered an essential component of people's life that is deeply rooted in the culture and history of the country;[26] it can be considered an underlying factor affecting the design of a palliative care system.

Regarding content, it is important to determine the executive policies of the service provision system. Countries that have been successful in providing palliative care have treated these services as part of their health system[27] and have integrated them with oncology care services,[28] while, according to the participants of the present study, no such thing is defined in the health system of Iran. A similar challenge posed is the classification of services. Theoretically, health services and referrals are presented at three levels in the health system of Iran; given this important infrastructure, these services have been designed in Iran in the form of the comprehensive national program for palliative and supportive cancer care at three levels, including the first-level care, which is provided in the community, health houses, and rural clinics. The most important pillar of the first-level palliative care is the referral system established which seeks to meet the patients’ needs at very little cost, and if necessary, refers them to higher levels of the service.[29] This scenario is the basis for providing services in successful health systems.[30]

Another major challenge in target setting is financing. Although after launching the health sector evolution plan, chemotherapy and radiotherapy have become free of charge for cancer patients if admitted to public hospitals, which is an almost unique advantage of the Iranian health-care system throughout the world,[31] there are no tariffs for other services such as home care and hospice. Designing service packages for different insured is a good financing policy that enables better access to health-care services. In some countries, such as Canada, the UK, and Italy, insurance tariffs have been defined by the private and public sectors and by charities, especially for providing home care and hospice services,[32] while there are still no home and hospice care centers in Iran.

According to the health policy analysis, process is concerned with people's performance and provision of services. The complexity of cancer and the various levels of services in palliative care mean that people's performance should be determined in different settings. The results indicate the lack of a defined job description for members of palliative care teams in Iran[17] and demonstrate the need for building a proper infrastructure.

Moreover, the limited palliative care services in Iran are often lacking in clinical guidelines and are only offered based on personal experience and knowledge. Some guidelines have been prepared and used locally in institutions. Examples include a guideline for spiritual services and pain protocol which significantly affects the patient's quality of life.[33,34] Meanwhile, as reported by the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (2013) in the US, the expansion and diversification of palliative care areas has led to the design and updating of guidelines and consequently the improvement of the quality of life, the continuity of care, and the standardized provision of services to the patients.[35]

The newly emerged palliative care system of Iran is faced with an inadequate training, awareness, and expertise among its health-care providers, especially nurses and physicians,[36] and the lack of public knowledge and awareness about the services offered through this system.[37] A reason for the inadequate training in this area is the lack of formal training in palliative care, which hinders the provision of these services. Developed countries have the experience of designing palliative care curricula, offering palliative care programs at the postgraduate level, and training both a general and an expert workforce.[32] In response to these needs, some measures have been taken in Iran, such as the design of an interdisciplinary curriculum for palliative care with the situation analysis and needs assessment of cancer patients; however, these measures may prove more effective if palliative care service points are also established.[38]

Actors play an important role in the design and implementation of policies. In Iran, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education is the top-level agency in charge of the health system and is responsible for planning and implementing health policies at the national level; part of this responsibility is delegated to medical science universities across the country. Considering that health-care services are classified into different levels in Iran, community-based health-care providers such as health workers (behvarz), midwives, GPs, and nurses can help in providing community-based palliative care. The interdisciplinary nature of palliative care with a team approach consisting of caregivers is a factor that contributes to the provision of services, cost reduction, and quality of life.[39] Continuous interdisciplinary education can help overcome the challenges in this area, such as the failures in teamwork, the ambiguities in the job description of health-care workers, and the lack of coordination between different sectors of the palliative care system. Attracting volunteer help to the palliative care system helps provide financial assistance to the patients and controls and coordinates the services provided by charitable entities and community volunteers and thus plays an important role in the development of a proper care system, since volunteers are one of the main funders of palliative care systems.[40]

Although the present study is one of the few studies that analyze palliative care system policies through the policy analysis framework, considering the extent of the issue and the fact that this study is qualitative and has been conducted on a small number of the stakeholders, the generalizability of the findings is low.

CONCLUSION

The growing number of cancer patients in Iran and the aging population, on the one hand, and the importance of health equity as a national policymaking goal, on the other hand, demonstrate the importance of designing a comprehensive care system more than ever. The success of a health system plan requires great attention to its aspects of social, political, and executive feasibility, the use of suitable scientific capacities, and consideration for the different actors involved. Making policies on this important issue with a comprehensive and holistic view of its components, including an emphasis on proper target setting, using methods of payment, regionalization and referral system in the health care system. In view of these findings, future studies are recommended to design a palliative care system for cancer patients and employ a pilot study to implement it as an operational model.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rasaf MR, Ramezani R, Mehrazma M, Rasaf MR, Asadi-Lari M. Inequalities in cancer distribution in Tehran; a disaggregated estimation of 2007 incidencea by 22 districts. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:483–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva: International Agency For Research on Cancer; 2012. International Agency For Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bingley A, Clark D. A comparative review of palliative care development in six countries represented by the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC) J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD. The public health strategy for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:486–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch T, Connor S, Clark D. Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global update. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:1094–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.PACT. Atomic Energy Agency PACT Program Experts’ Recommendations and the World Health Organization on Cancer Control Program in Iran. 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.login.research.ac.ir/Repository/UploadSenderSubSystem/32416bdd-f3f5-4117-a0b3-6a295bf3e1d1.pdf .

- 7.Ddungu H. Palliative care: What approaches are suitable in developing countries? Br J Haematol. 2011;154:728–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higginson IJ, Hart S, Koffman J, Selman L, Harding R. Needs assessments in palliative care: An appraisal of definitions and approaches used. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:500–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walt G, Gilson L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: The central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. 1994;9:353–70. doi: 10.1093/heapol/9.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Making Health Policy. UK: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walt G. Health policy: an introduction to process and power. 1994:226. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H, Murray SF, Brugha R, Gilson L, et al. ’Doing’ health policy analysis: Methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23:308–17. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 1994;2:163–94. [Google Scholar]

- 15.London: The Economist Intelligence Unit; 2015. Economist Intelligence Unit. The 2015 Quality of Death Index: Ranking Palliative Care Across the World. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Research Center. Development of a Comprehensive National Program for Palliative and Supportive Cancer Care Project. [Last accessed on 2014 Nov 8]. Available at: http://crc.tums.ac. ir/Default.aspx.tabid=519 .

- 17.Khoshnazar TA, Rassouli M, Akbari ME, Lotfi-Kashani F, Momenzadeh S, Haghighat S, et al. Structural challenges of providing palliative care for patients with breast cancer. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:459–66. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.191828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aldridge MD, Hasselaar J, Garralda E, van der Eerden M, Stevenson D, McKendrick K, et al. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: A literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30:224–39. doi: 10.1177/0269216315606645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sajjadi M, Rassouli M, Abbaszadeh A, Brant J, Majd HA. Lived experiences of "Illness uncertainty" of Iranian cancer patients: A Phenomenological hermeneutic study. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:E1–9. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox K, Bird L, Arthur A, Kennedy S, Pollock K, Kumar A, et al. Public attitudes to death and dying in the UK: A review of published literature. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3:37–45. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, Kernohan W. Exploring public awareness of palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care. 2013;28:273–80. doi: 10.1177/0269216313502372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramanayake RP, Dilanka GV, Premasiri LW. Palliative care; role of family physicians. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5:234–7. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.192356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bajwah S, Higginson IJ. General practitioners’ use and experiences of palliative care services: A survey in South East England. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silbermann M, Arnaout M, Daher M, Nestoros S, Pitsillides B, Charalambous H, et al. Palliative cancer care in Middle Eastern countries: Accomplishments and challenges. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 3):15–28. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemati S, Rassouli M, Ilkhani M, Baghestani AR. The spiritual challenges faced by family caregivers of patients with cancer: A Qualitative study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2017;31:110–7. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rassouli M, Khanali L, Farahani AS. Palliative care perspectives and practices in the Islamic republic of Iran, and their implication on patients’ quality of life. In: Silbermann M, editor. Palliative Care: Perspectives, Practices and Impact on Quality of Life. New York: Publisher In Press, Nova Scientific; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Strengthening of Palliative Care as a Component of Comprehensive Care Throughout the Life Course. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higginson IJ, Evans CJ. What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families? Cancer J. 2010;16:423–35. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181f684e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirvani N, Ashrafian Amiri H, Motlagh M, Kabir M, Maleki MR, Shabestani MA, et al. Introduction to Health Sector Reform. 1st Ed. Tehran: Asare Mouaser; 2006. pp. 233–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.May P, Hynes G, McCallion P, Payne S, Larkin P, McCarron M, et al. Policy analysis: Palliative care in Ireland. Health Policy. 2014;115:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rassouli M, Sajjadi M. Switzerland: Springer; 2016. Cancer care in countries in transition: The Islamic Republic of Iran. Cancer Care in Countries and Societies in Transition; pp. 317–36. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centeno Cortes C, Pons Izquierdo JJ, Lynch T, Donea O, Rocafort J, Clark D. EAPC atlas of palliative care in Europe 2013 cartographic edition. Eur Assoc Palliat Care. 2013:176–334. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Memaryan N, Jolfaei AG, Ghaempanah Z, Shirvani A, Vand H, Ghahari S, et al. Spiritual Care for Cancer Patients in Iran. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 2016;17:4289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services- Nursing Administration. [Last accessed on 2017 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.amuzesh.muq.ac.ir/uploads/pain.pdf .

- 35.Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project; 2013. Dahlin Constance, Care National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mojen LK. Palliative care in Iran: The past, the present and the future. History. 2016;6:8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motlagh A, Yaraei N, Mafi AR, Hosseini Kamal F, Yaseri M, Hemati S, et al. Attitude of cancer patients toward diagnosis disclosure and their preference for clinical decision-making: A national survey. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17:232–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irajpour A, Alavi M, Izadikhah A. Situation analysis and designing an interprofessional curriculum for palliative care of the cancer patients. Iran J Med Educ. 2015;14:1047–56. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott R. London: Hospice UK; 2014. Volunteering: Vital to Our Future. How to Make the Most of Volunteering in Hospice and Palliative Care. [Google Scholar]