Abstract

Background

The detrimental impact of smoking on health has been widely documented since the 1960s. Numerous studies have also quantified the economic cost that smoking imposes on society. However, these studies have mostly been in high income countries, with limited documentation from developing countries. The aim of this paper is to measure the economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases in countries throughout the world, including in low- and middle-income settings.

Methods

The Cost of Illness approach is used to estimate the economic cost of smoking attributable-diseases in 2012. Under this approach, economic costs are defined as either ‘direct costs' such as hospital fees or ‘indirect costs’ representing the productivity loss from morbidity and mortality. The same method was applied to 152 countries, which had all the necessary data, representing 97% of the world's smokers.

Findings

The amount of healthcare expenditure due to smoking-attributable diseases totalled purchasing power parity (PPP) $467 billion (US$422 billion) in 2012, or 5.7% of global health expenditure. The total economic cost of smoking (from health expenditures and productivity losses together) totalled PPP $1852 billion (US$1436 billion) in 2012, equivalent in magnitude to 1.8% of the world's annual gross domestic product (GDP). Almost 40% of this cost occurred in developing countries, highlighting the substantial burden these countries suffer.

Conclusions

Smoking imposes a heavy economic burden throughout the world, particularly in Europe and North America, where the tobacco epidemic is most advanced. These findings highlight the urgent need for countries to implement stronger tobacco control measures to address these costs.

Keywords: Economics, Smoking Caused Disease, Global health

Introduction

The detrimental impact of smoking on physical health and well-being has been widely documented throughout the world since the early 1960s.1 2 Numerous studies have also quantified the economic cost that smoking imposes on society. However, these studies have mostly been in high-income countries, with less documentation available from developing countries.3 Today, the growing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in developing countries has further heightened interest in monitoring the economic cost of associated risk factors such as tobacco use.

Global concern about the impact of NCDs resulted in the 2012 Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases.4 This Declaration notes with grave concern the ‘increased burden that NCDs impose through impoverishment from long-term treatment costs, and from productivity losses that threaten household incomes and the economies of Member States’. In 2015, the UN General Assembly also adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.5 It includes 17 Goals (sustainable development goals (SDGs)) that all Member States have agreed to achieve by 2030. SDG 3 to ‘ensure healthy lives and promoting well-being for all ages’ includes target 3.4 to reduce by one-third premature mortality from NCDs, and target 3.a to strengthen country implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC).5–7

The WHO has previously noted that—despite some good progress—many countries have yet to introduce tobacco control measures at their highest level of implementation. This has left their populations at increased risk from tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure, with the illness, disability and death they cause.8 All countries have the ability to implement proven cost-effective tobacco control policies to protect the health of their citzens.9 10 Tobacco control can potentially make a significant contribution towards the achievement of development priorities such as the SDGs.

The aim of this study is to measure the global economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases (ie, those caused by direct exposure to smoking). These findings will highlight the need for countries to implement more comprehensive tobacco control measures to address these economic costs, while also helping to achieve global development priorities under the SDGs.

Methods

This study adopts a classic Cost of Illness approach to modelling the economic impact of an illness as developed by Rice and colleagues in the 1960s.3 Under this approach, the gross economic impact of an illness is divided into ‘direct costs’ incurred in a given year (eg, hospitalisation and medications) and ‘indirect costs’ representing the value of lost productivity in current and future years due to disability and mortality. Direct and indirect costs are then summed to provide the overall economic cost to society, often expressed as a percentage of annual gross domestic product (GDP).11 This approach has been used in the vast majority of studies on the economic costs of smoking, particularly in developing countries.3 12 Some variations of this approach have been developed over time, for example, the life cycle approach to direct cost estimation. We compare these developments with the classic approach in our discussion section.

We were able to collect the necessary data to complete our calculations for 152 countries, representing 97% of the world's smokers. The countries were grouped according to World Bank income status and WHO region. Key results for all countries are contained in the online supplementary material file. The findings are reported in international dollars using International Monetary Fund (IMF) purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates for 2012. The use of international dollars (PPP$s) is common practice to ensure that the estimation of economic costs in different countries are comparable, and properly reflect underlying differences in the cost of living for people in countries at different levels of development.13 However, we also report the key findings in US dollar (US$) terms.

tobaccocontrol-2016-053305supp001.pdf (367.4KB, pdf)

Estimation of direct costs

Cost of Illness studies often categorise direct costs into either healthcare or non-healthcare expenditures. Healthcare expenditures are those incurred from the diagnosis and treatment of smoking-attributable diseases (hospitalisation, physician services, medications, etc), while non-healthcare expenditures are incurred outside of the health system (eg, property loss from fires caused by cigarettes). For the purpose of this study, we limit our investigation of direct costs to healthcare expenditure.

A literature search was undertaken to gather data on smoking-attributable healthcare expenditures in different countries. We searched four bibliographic databases (EconLit, EMBASE, PubMed and Cochrane), checked the reference list of recent systematic reviews and searched Google for grey literature.12 Studies were included if they were published in the past 25 years, calculated health costs on an annual basis and included at least three major smoking-attributable diseases. The reasoning behind these search criteria was to assess the finding of studies that were comparable in scale and scope. Titles and abstracts were screened before potentially eligible studies were assessed by two reviewers. Studies were then excluded if they were funded by the tobacco industry, or were for areas that are not UN Member States (we lack the background data for provinces or special administrative regions). Overall, the literature search found 33 studies covering 44 countries.14–46

These 44 countries are shown in table 1 alongside background information such as the World Bank income status and smoking-attributable death (SAD) rate for each population as reported by WHO.47 Based on the 2012 WHO Global Health Expenditure database, these 44 countries accounted for 86% of total health expenditure (THE) worldwide in international dollar terms.48

Table 1.

Health cost studies of smoking-attributable diseases, 1990–2015

| Study authors | Country name | Income group | Diseases included | SAD rate | SAF (% health expenditure) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadilhac et al 14 (2011) | Australia | HIC | HS | 170 | 4.8 |

| Collins and Lapsley15 (2002) | Australia | HIC | M C R S O | 170 | 3.9 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Austria | HIC | M C R | 188 | 5.8 |

| WHO17 (2005) | Bangladesh | LIC | M C R T | 255 | 6.7 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Belgium | HIC | M C R | 295 | 6.4 |

| Pinto et al 18 (2015) | Brazil | UMIC | M C R S | 143 | 6.1 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Bulgaria | UMIC | M C R | 296 | 4.0 |

| Rehm et al 19 (2006) | Canada | HIC | M C R O | 239 | 3.7 |

| Sung et al 20 (2009) | China | UMIC | M C R T | 137 | 3.1 |

| Yang et al 21 (2011) | China | UMIC | M C R T | 137 | 3.0 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Cyprus | HIC | M C R | 101 | 3.6 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Czech Rep | HIC | M C R | 296 | 7.2 |

| Sovinova et al 22 (2002) | Czech Rep | HIC | M C R O | 296 | 11.0 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Denmark | HIC | M C R | 358 | 7.5 |

| Rasmussen et al 23 (2004) | Denmark | HIC | M C R | 358 | 9.2 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Estonia | HIC | M C R | 349 | 9.6 |

| Taal et al 24 (2004) | Estonia | HIC | M C R O | 349 | 7.0 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Finland | HIC | M C R | 155 | 5.3 |

| GHK16 (2009)1 | France | HIC | M C R | 193 | 6.1 |

| GHK16 (2009)1 | Germany | HIC | M C R | 215 | 5.9 |

| Neubauer et al 25 (2006) | Germany | HIC | M C R T | 215 | 3.2 |

| Ruff et al 26 (2000) | Germany | HIC | M C R | 215 | 4.3 |

| Welte et al 27 (2000) | Germany | HIC | M C R T O | 215 | 4.9 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Greece | HIC | M C R | 238 | 6.4 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Hungary | UMIC | M C R | 495 | 11.9 |

| John et al 28 (2009) | India | LMIC | M C R T | 112 | 3.6 |

| John et al 29 (2015) | India | LMIC | M C R T | 112 | 3.3 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Ireland | HIC | M C R | 284 | 7.1 |

| Ginsberg and Geva30 (2014) | Israel | HIC | M C R O | 114 | 2.6 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Italy | HIC | M C R | 211 | 6.3 |

| Izumi et al 31 (2001) | Japan | HIC | HS | 200 | 3.8 |

| GHK16 (2009)1 | Latvia | HIC | M C R | 326 | 8.1 |

| Chaaban et al 32 (2010) | Lebanon | UMIC | M C R | 121 | 4.2 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Lithuania | HIC | M C R | 282 | 8.3 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Luxemburg | HIC | M C R | 214 | 6.5 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Malta | HIC | M C R | 150 | 5.5 |

| Reynales-Shigematsu et al 33 (2006) | Mexico | UMIC | M C R | 65 | 4.3 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Netherlands | HIC | M C R | 268 | 7.2 |

| van Genugten et al 34 (2004) | Netherlands | HIC | M C R | 268 | 8.5 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Poland | HIC | M C R | 353 | 6.6 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Portugal | HIC | M C R | 155 | 4.5 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Romania | UMIC | M C R | 295 | 5.0 |

| Potapchik and Popovich35 (2014) | Russia | UMIC | M C R | 398 | 13.0 |

| Quah et al 36 (2006) | Singapore | HIC | M, C, R, F | 157 | 1.8 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Slovakia | HIC | M C R | 268 | 6.1 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Slovenia | HIC | M C R | 279 | 6.6 |

| Kang et al 37 (2003) | South Korea | HIC | M C R O | 211 | 7.3 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Spain | HIC | M C R | 185 | 6.0 |

| Bolin et al 38 (2007) | Sweden | HIC | M C R O | 147 | 1.2 |

| GHK16 (2009) | Sweden | HIC | M C R | 147 | 4.9 |

| Priez et al 39 (1999) | Switzerland | HIC | M C R | 153 | 3.4 |

| Leartsakulpanitch et al 40 (2007) | Thailand | UMIC | M C R | 174 | 3.6 |

| Allender et al 41 (2009) | UK | HIC | M C O | 330 | 5.5 |

| GHK16 (2009) | UK | HIC | M C R | 330 | 6.4 |

| Scarborough et al 42 (2011) | UK | HIC | M C O | 330 | 4.7 |

| CDC43 (2002) | USA | HIC | M C R O | 318 | 6.0 |

| Xu et al 44 (2015) | USA | HIC | HS | 318 | 8.7 |

| Hoang Anh et al 45 (2014) | Vietnam | LMIC | M C R | 228 | 5.8 |

| Ross et al 46 (2007) | Vietnam | LMIC | M C R | 228 | 4.3 |

C, cardiovascular and circulatory diseases; HIC, high income; HS, health system; LIC, low income; LMIC, lower middle income; M, malignant neoplasms; O, other; R, non-malignant respiratory disease; S, secondhand smoke; SAD, smoking-attributable death; SAF, smoking-attributable fraction; T, tuberculosis; UMIC, upper middle income.

The final column of table 1 shows the proportion of health expenditure that each of these studies found to be attributable to smoking. These smoking-attributable fractions (SAFs) were reported by the authors, with the exception of the studies for Australia, Bangladesh, Brazil and Thailand. We calculated the SAF for these four countries by dividing the authors' estimate of the absolute amount of smoking-attributable health expenditure (SAHE) by THE for the relevant year.

The dollar amount of SAHEi in all of these 44 countries was then calculated for 2012 as:

where  is the smoking-attributable fraction for each country

is the smoking-attributable fraction for each country  and

and is total health expenditure in PPP$ for 2012.

is total health expenditure in PPP$ for 2012.

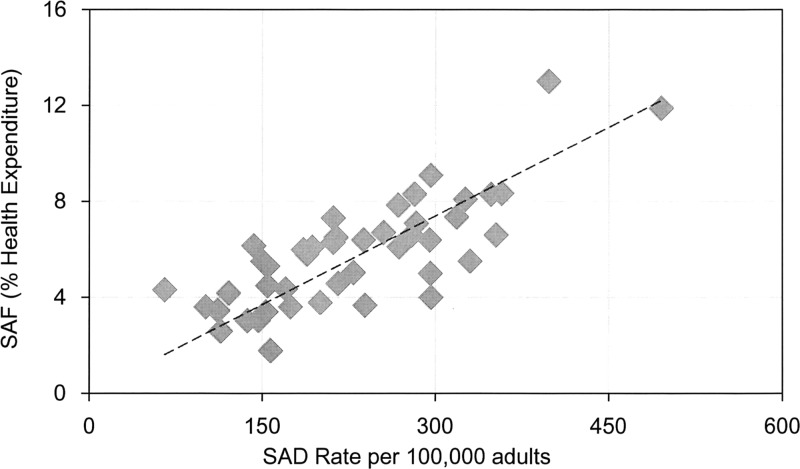

Simple linear regression analysis was then used to estimate the SAF in countries not included in table 1. Figure 1 shows that there is a strong correlation between the SAF and the SAD rate in our sample of 44 countries form the literature search. Although this correlation alone does not prove causation, the direction of the relationship seems clear (ie, as the disease burden from smoking increases, a greater share of health resources is allocated to treat them). Simple linear regression analysis confirms the statistical strength of this relationship, with an adjusted R2 of 0.9219 and a p value of <0.001. Note that GDP/capita was initially included in the analysis to control for income, but was found to be insignificant. The model was also tested for heteroscedasticity using White's test and specification error for omitted variables using Ramsey regression specification-error test in STATA 13. The regression is run through the origin after finding insignificant constant term.

Figure 1.

Smoking-attributable fraction (SAF) for healthcare expenditure and smoking-attributable death (SAD) rate.

The regression coefficient from the estimated equation  and the SAD rate was used to estimate the SAF for health expenditure in the countries not included in table 1. These SAFs were then multiplied by THE for each country as before to arrive at the SAHE. Note—since the majority of global health expenditure has already been accounted for by the 44 countries in table 1—this approach was applied to countries that constitute just 14% of total global health expenditure.

and the SAD rate was used to estimate the SAF for health expenditure in the countries not included in table 1. These SAFs were then multiplied by THE for each country as before to arrive at the SAHE. Note—since the majority of global health expenditure has already been accounted for by the 44 countries in table 1—this approach was applied to countries that constitute just 14% of total global health expenditure.

Estimation of indirect costs

Indirect costs measure the economic loss associated with excess levels of morbidity and mortality caused by smoking-attributable diseases. This economic loss has been quantified in our study using the human capital method (HCM), which calculates the present value of labour productivity loss due to morbidity and mortality. As discussed, the HCM has also been used in the vast majority of studies on the economic cost of smoking.3 12

The first step is to establish the physical burden of disease among smokers in the working-age population. This study uses updated WHO estimates for each Member State of the number of SADs among adults aged 30+in 2012 (WHO. WHO global report: mortality attributable to tobacco. Geneva; World Health Organization; forthcoming). These estimates are based on the methodology pioneered by Peto (1992) with a further explanation available in WHO (2012).47 49 The causes of death include tuberculosis, lower respiratory infections, malignant neoplasms, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases. The age cohorts include adults aged 30–59 and 60–69 years, with the latter being the best available approximation for age of retirement.

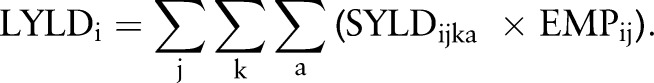

With respect to morbidity, earlier WHO estimations in 2004 included the number of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) lost to smoking—where the DALY measure defines morbidity as the number of years lost to disability (YLD). This study updates the 2004 estimates of smoking-attributable years lost to disability  to 2012 using the following calculation:

to 2012 using the following calculation:

where  is the fraction of years lost to disability attributable to smoking by gender

is the fraction of years lost to disability attributable to smoking by gender  , age

, age  and disease

and disease for country

for country  in 2004, and

in 2004, and  is the absolute number of years lost to disability in 2012 for the same gender, age, disease and country. As the SAF for YLDs in 2012 was not available, the fraction from 2004 was instead applied to the disability statistics contained in the 2012 Global Burden of Disease database.50

is the absolute number of years lost to disability in 2012 for the same gender, age, disease and country. As the SAF for YLDs in 2012 was not available, the fraction from 2004 was instead applied to the disability statistics contained in the 2012 Global Burden of Disease database.50

The estimates of smoking-attributable disability and mortality were then converted into equivalent labour years lost using the World Bank employment-to-population ratio for each country.51 The number of labour years lost due to disability  was calculated as the smoking-attributable years lost to disability (

was calculated as the smoking-attributable years lost to disability ( for all diseases by gender

for all diseases by gender  and age

and age  multiplied by the corresponding employment-to-population ratio

multiplied by the corresponding employment-to-population ratio  for each country

for each country  and gender

and gender :

:

|

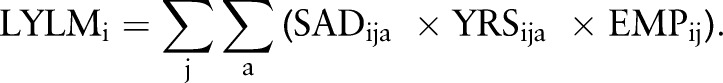

The number of labour years lost due to mortality includes all future labour years lost until retirement at age 69. This total was calculated as the sum of SADs (SADija) by gender

includes all future labour years lost until retirement at age 69. This total was calculated as the sum of SADs (SADija) by gender  and age group (a)for country

and age group (a)for country  multiplied by the average years until reaching retirement

multiplied by the average years until reaching retirement  after accounting for survival rates through retirement age using WHO life tables, and then by the corresponding employment-to-population ratio:

after accounting for survival rates through retirement age using WHO life tables, and then by the corresponding employment-to-population ratio:

|

The final step in the HCM is to calculate the total loss in productivity associated with the decrease in labour years. Note that the loss in productivity from disability is calculated annually, while the loss from death is calculated as the present value of productivity losses over all future years that an individual would have worked had they not died prematurely from a smoking-attributable disease. The value of lost productivity due to disability  in each country was calculated as follows:

in each country was calculated as follows:

where  is the combined number of male and female labour years lost due to disability and (PRODi) is the amount of GDP generated per adult worker in PPP international dollar terms for 2012. Note that GDP/worker was calculated for each country by dividing national GDP by total employment in the 30–69 working-age cohorts.51

52

is the combined number of male and female labour years lost due to disability and (PRODi) is the amount of GDP generated per adult worker in PPP international dollar terms for 2012. Note that GDP/worker was calculated for each country by dividing national GDP by total employment in the 30–69 working-age cohorts.51

52

As discussed, the present value of lost productivity due to mortality  includes current and future labour years lost and was calculated as:

includes current and future labour years lost and was calculated as:

|

where  is the growth rate of labour productivity in country (i) and

is the growth rate of labour productivity in country (i) and are the discount rates. The sum is over the age of premature death up until the age of retirement at 69 years. The IMF's forecast of growth in GDP/capita was used as a proxy for productivity growth

are the discount rates. The sum is over the age of premature death up until the age of retirement at 69 years. The IMF's forecast of growth in GDP/capita was used as a proxy for productivity growth . As per standard practice in health economics, a discount rate of 3% was applied to all countries.53

. As per standard practice in health economics, a discount rate of 3% was applied to all countries.53

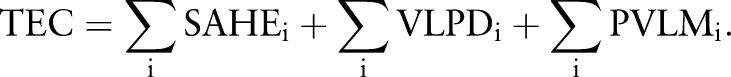

The total economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases  is given by the sum of the direct and indirect costs of morbidity and mortality aggregated over all countries:

is given by the sum of the direct and indirect costs of morbidity and mortality aggregated over all countries:

|

Summary of data sources

THE for each member state in 2012 was taken from the WHO Global Health Expenditure database.48 Smoking-attributable mortality in 2012 was sourced from a forthcoming update of the WHO global report on mortality attributable to tobacco, while smoking-attributable disability was separately updated to 2012 using the Global Burden of Disease database.50 Employment-to-population ratios for each Member State was taken from the World Bank World Development Indicators.51 GDP and GDP/capita in PPP international dollars for each Member State was sourced from the IMF World Economic Outlook.52

Findings

Health burden and labour loss

Table 2 summarises the physical burden of disease and labour force loss due to smoking-attributable diseases in 2012 categorised by World Bank income group and WHO region. Smoking caused 2.1 million deaths and 13.6 million years lost to disability (YLDs) among adults aged 30–69. Note that these 2.1 million deaths reflect a subset of the total 5 million deaths directly attributable to smoking.47 In total, smoking-attributable diseases accounted for 12% of all deaths among the world's working-age population, with this proportion being highest in Europe and the Americas where the tobacco epidemic is at a late or mature stage of development.

Table 2.

Smoking-attributable burden of disease and labour force loss among adults aged 30–69 years

| Burden of disease |

Labour force loss |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years lost to disability | Adult deaths | All deaths | Lost workers | Labour lost: disability | Labour lost: mortality | |

| (000 years) | (000s) | (per cent) | (000s) | (000 years) | (000 years) | |

| High-income | 4717 | 764 | 23 | 462 | 2721 | 5409 |

| Upper-middle-income | 3539 | 581 | 10 | 386 | 2300 | 4919 |

| Lower-middle-income | 4213 | 685 | 9 | 501 | 2988 | 6862 |

| Low-income | 1139 | 82 | 6 | 63 | 827 | 830 |

| World | 13 607 | 2112 | 12 | 1412 | 8837 | 18 021 |

| Africa | 361 | 37 | 3 | 20 | 204 | 258 |

| Americas | 2863 | 336 | 15 | 209 | 1730 | 2591 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 714 | 76 | 6 | 51 | 442 | 710 |

| Europe | 3206 | 722 | 26 | 433 | 1817 | 5287 |

| Southeast Asia | 3863 | 558 | 10 | 422 | 2832 | 5663 |

| Western Pacific | 2601 | 382 | 9 | 277 | 1813 | 3512 |

The main impact on the labour market occurs via the permanent loss of workers due to early mortality. In 2012, it is estimated that the total 2.1 million SADs included 1.4 million deaths in those adults who otherwise would have been in the workforce (eg, representing a global adult employment rate of around 67%). The number of labour years lost (LYLs) due to smoking-related mortality includes the future labour years foregone until retirement. The number of LYLs due to smoking-attributable diseases came to 26.8 million years, with 18.0 million years lost due to mortality and 8.8 million years lost due to disability.

Smoking-attributable health expenditure

Table 3 summarises the global economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases in 2012, with the two main components being direct smoking-attributable health expenditures (SAHE) and indirect costs from productivity losses due to smoking-attributable disability and mortality. These findings are also categorised by World Bank income group and WHO region.

Table 3.

The economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases, PPP international dollars

| Direct Cost |

Indirect Cost |

Total Cost |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAHE | THE | Disability | Mortality | Total | GDP | |

| (PPP$ mn) | Per cent | (PPP$ mn) | (PPP$ mn) | (PPP$ mn) | Per cent | |

| High-Income | 369 002 | 6.5 | 275 097 | 478 833 | 1 122 932 | 2.2 |

| Upper-Middle-Income | 75 031 | 4.0 | 74 456 | 205 091 | 354 578 | 1.2 |

| Lower-Middle-Income | 21 236 | 3.9 | 91 447 | 246 365 | 359 048 | 1.7 |

| Low-Income | 2011 | 4.0 | 5272 | 8300 | 15 583 | 1.2 |

| World | 467 279 | 5.7 | 446 273 | 938 589 | 1 852 141 | 1.8 |

| Africa | 4566 | 3.5 | 5571 | 9317 | 19 454 | 1.0 |

| Americas | 239 559 | 6.7 | 159 445 | 226 886 | 625 890 | 2.4 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 6583 | 2.0 | 13 291 | 24 807 | 44 680 | 0.6 |

| Europe | 141 787 | 6.6 | 134 552 | 339 503 | 615 843 | 2.5 |

| Southeast Asia | 15 299 | 4.1 | 83 880 | 220 320 | 319 499 | 1.8 |

| Western Pacific | 59 485 | 3.8 | 49 534 | 117 756 | 226 775 | 0.9 |

GDP, gross domestic product; THE, total health expenditure; PPP, purchasing power parity; SAHE, smoking- attributable health expenditure

SAHE totalled PPP$467 billion (equivalent to US$422 billion) in 2012, and accounted for 5.7% of THE worldwide. This proportion was highest in HICs, the Americas and Europe. In Eastern Europe—where the tobacco epidemic is generally the most advanced—our calculations suggest that smoking is responsible for around 10% of THE in this subregion.

Indirect and total economic loss

The indirect cost of smoking-attributable diseases is estimated at PPP$1385 billion (US$1014 billion), with disability accounting for PPP$446 billion (US$357 billion) and mortality accounting for PPP$939 billion (US$657 billion), respectively. The total economic cost of smoking is thus estimated at PPP$1852 billion (US$1436 billion), equivalent in magnitude to 1.8% of the world's annual GDP. Almost 40% of the total economic cost occurs in low-income and middle-income countries reflecting the substantial loss these countries suffer due to tobacco use. Indeed, the four BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) account for as much as 25% of the total economic cost of smoking.

The economic burden of smoking is proportionately highest in Europe, where the cost of smoking-attributable diseases is equivalent in magnitude to 2.5% of the region's annual GDP. This includes significant subregional variation, with the costs in Eastern Europe amounting to as much as 3.6% of GDP compared with 2.0% in the rest of Europe. Similarly, the costs in Canada and the USA combined represent 3.0% of GDP compared with 1.0% in the rest of the Americas. The cost of smoking-attributable diseases is proportionately lowest in Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean region where smoking prevalence and the intensity of tobacco use is currently low compared to the ‘high burden’ populations like Eastern Europe. Many countries in Africa and other regions are still at an early stage of the epidemic, and the full societal cost of smoking may not be evident yet.

Discussion

In this section, we discuss the findings of our sensitivity analyses, highlight the limitations of our study for future improvement, and discuss some alternatives to the classic Cost of Illness approach.

Sensitivity analysis

We explored the sensitivity of our findings for smoking-attributable healthcare expenditure by using the CI on the coefficient for SAF (0.022817; 0.026469) and the range of estimates for the 44 countries in table 1. Based on this sensitivity test, smoking-attributable health expenditure ranges between PPP$418 and 514 billion globally, representing between 5.12% and 6.30% of THE. Similarly, the total economic cost of smoking ranged between PPP$1803 and 1899 billion globally—equivalent in magnitude to between 1.76% and 1.85% of worldwide GDP.

Study limitations

The estimates in our study relate to direct exposure through smoking and do not include the harm from secondhand smoke or smokeless forms of tobacco. Secondhand smoke is responsible for around 600 000 deaths per annum and their inclusion would thus have a measurable impact on our estimate of the economic cost of smoking.54 Smokeless tobacco products are widely used in many countries notably in South-East Asia. In India, it has been estimated that smokeless tobacco accounts for as much as 30% of all medical expenditures attributable to tobacco use.29 Given more detailed monitoring and statistics, these other forms of exposure can be included in future estimations.

Our estimation of health expenditures relies on past studies in this field of research (table 1). These studies examine different diseases and use different techniques to calculate the SAF. Thus, we cannot state that the findings are fully comparable. However, our search criteria meant that only studies with at least three diseases—typically malignant neoplasms, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases—were included in our sample. As these conditions account for the vast majority (>90%) of SADs, we can claim a reasonable degree of comparability. This is also evident in the statistical strength of the correlation, as well as the tight range of results we found in our sensitivity analysis.

Our estimation of indirect cost uses the Human Capital Method (HCM) to estimate loss in production. While the HCM is a convenient measure for macroeconomic analysis, it does have some inherent limitations. For example, the HCM only calculates the indirect loss for people who are ‘economically active’ and may not reflect the full loss in societal welfare. Wage and productivity differentials between countries also mean that the HCM attributes greater loss to workers in high-income countries relative to those in low-income and middle-income countries. Note that our use of PPP$ only partly adjusts for this bias. Finally, the HCM does not capture the potential dynamic linkages between health and economic growth through channels such as demography, education and investment.

Methodological considerations

The healthcare costs associated with smoking have traditionally been measured on an annual basis. However, there is a growing body of literature that uses longitudinal information to measure these costs on a life cycle basis.55 This life cycle approach yields a richer source of evidence including for cost-effectiveness analyses. Nonetheless, the annual approach remains a valid form of analysis in its own right, and our contribution is to highlight the risk of ‘cost escalation’ particularly for countries that are still at the early stage of the tobacco epidemic (refer figure 1).

Several alternatives to the Human Capital Method (HCM) have been proposed in recent years. For example, the Friction Cost Method (FCM) aims to provide a more realistic description of the loss in economic output by measuring the time it takes employers to replace workers.56 Under the FCM, long-term absentees are replaced and production levels are restored after a period of adjustment. The length of adjustment depends on the availability of labour (eg, unemployment). The FCM has been criticised for lacking theoretical underpinnings, and has not been taken-up widely to date.

The Willingness To Pay (WTP) approach uses different techniques to quantify peoples willingness to pay to avoid death.57 This includes intangible factors like the value of leisure time or the absence of pain and suffering. The WTP approach has gained traction due to its grounding in welfare economics. The FCM yields the lowest estimate of indirect economic loss, while WTP yields the highest. The HCM yields estimates that are in-between. The HCM can also be applied relatively easily and consistently across countries, and arguably continues to be the most widely accepted approach. Nonetheless, future updates of this study might usefully include one or more of these alternative approaches together with the HCM.

Conclusion

We found that diseases caused by smoking accounted for 5.7% of global health expenditures in 2012, while the total economic cost of smoking was equivalent to 1.8% of global GDP. Smoking imposes a heavy economic burden throughout the world, particularly in Europe and North America where the tobacco epidemic is most advanced. These findings highlight the urgent need for all countries to implement comprehensive tobacco control measures to address these economic costs, while also helping to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals of Member States.

What this paper adds.

The detrimental impact of smoking on physical health and well-being has been widely documented throughout the world since the early 1960s. Numerous studies have also quantified the economic burden that smoking imposes on society through avoidable healthcare expenditures and via indirect losses associated with morbidity and mortality.

These economic studies have mostly been undertaken in high-income countries, with less documentation available in developing countries. The rapidly rising burden of non-communicable diseases in developing countries has further heightened interest in measuring and monitoring the economic cost of associated risk factors such as tobacco use.

This paper measures the economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases throughout the world, including in low- income and middle-income countries. To the best of our knowledge, there has previously been no peer reviewed study published on this subject. The same Cost of Illness method was applied to 152 countries, representing 97% of the world's smokers. We found that diseases caused by smoking accounted for 5.7% of global health expenditure in 2012, while the total economic cost of smoking was equivalent to 1.8% of global gross domestic product (GDP).

Acknowledgments

We thank Sameer Pujari, Avdyl Ramaj and Stephanie Kandasami for their assistance in the literature search and data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: MG led the study design, the literature search, the modelling and the drafting of the manuscript. NN and ET contributed to the study design, the model testing and drafting of the manuscript.

Disclaimer: The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article, and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. USDHHS. The health consequences of smoking: a report to the Surgeon General. Washington DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global burden of disease study. Lancet 1997;349:1498–15. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO. Economics of tobacco toolkit: assessment of the economic costs of smoking. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. UN. Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases. New York: United Nations General Assembly, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. UN. Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United National General Assembly, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO. Health in 2015: from MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2015: raising taxes on tobacco. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. WHO. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2008: the MPOWER package. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO & WEF. From burden to “best buys": reducing the economic impact of NCDs in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization & World Economic Forum, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. WHO. WHO guide to identifying the economic consequences of disease and injury. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guindon E, Tobin P, Lim M, et al. The costs attributable to tobacco use: a critical review of the literature. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Bank. What is purchasing power parity? Washington DC: International Comparison Programme, World Bank, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cadilhac DA, Magnus A, Sheppard L, et al. The societal benefits of reducing six behavioural risk factors: an economic modelling study from Australia. BMC Public Health 2011;11:483 10.1186/1471-2458-11-483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Collins D, Lapsley H. The costs of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug abuse to Australian society in 2004/05. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16. GHK. A study on liability and the health costs of smoking. London, GHK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17. WHO. Impact of tobacco-related illnesses in Bangladesh. Dhaka: World Health Organization, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pinto M, Pichon-Riviere A, Bardach A. The burden of smoking-related diseases in Brazil: mortality, morbidity and costs. Cad. Saude Publica 2015;31:1283–97. 10.1590/0102-311X00192013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rehm K, Baliunas D, Brochu S, et al. The costs of substance abuse in Canada. Ontario: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sung HY, Wang L, Jin S, et al. Economic burden of smoking in China, 2000. Tob Control 2006;15 (Suppl I):i5–i11. 10.1136/tc.2005.015412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang L, Sung HY, Mao Z, et al. Economic Costs Attributable to Smoking in China: update and an 8-year Comparison, 2000–2008. Tob Control. 2011;20:266–72. 10.1136/tc.2010.042028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sovinová H, Csémy L, Procházka B, et al. Smoking attributable hospital treatment, treatment costs and smoking attributable mortality in the Czech Republic in 2002. Cent Eur J Public Health 2007;15:79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rasmussen SR, Prescott E, Sorensen TI, et al. The total lifetime cost of smoking. Eur J Public Helath 2004;14:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taal A, Kiivet R, Hu T. The economics of tobacco in Estonia. Health, nutrition and population discussion paper series, economics of tobacco control paper no. 19. Washington DC: World Bank, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neubauer S, Welte R, Beiche A, et al. Mortality, morbidity and costs attributbale to smoking in Germany: update and a 10-year comparison. Tob Control. 2006;15:464–71. 10.1136/tc.2006.016030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruff LK, Volmer T, Nowak D, et al. The economic impact of smoking in Germany. Eur Respir J 2000;16:385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Welte R, Koing H, Leidl R. The costs of health damage and productivity losses attributable to cigarette smoking in Germany. Tob Control 1999;8:290–300.10599574 [Google Scholar]

- 28. John RM, Sung HY, Max W. Economic cost of tobacco use in India, 2004. Tob Control 2009;18:138–43. 10.1136/tc.2008.027466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. John R, Rout S, Kumar B, et al. Economic burden of tobacco-related diseases in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ginsberg G, Geva H. The burden of smoking in Israel–attributable mortality and costs—2014. Israel J Health Policy Res 2014;3:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Izumi Y, Tsuji I, Ohkubo T, et al. Impact of smoking habit on medical care use and its costs: a prospective observation of National Health Insurance beneficiaries in Japan. In J Epidemiol 2001;30:616–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chaaban J, Naamani N, Salti N. The economics of tobacco in Lebanon: an estimation of the social costs of tobacco consumption. Beirut: American University in Beirut Tobacco Control Research Group, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Rodríguez-Bolaños RL, Jimenez JA, et al. Health care costs attributable to tobacco consumption on a national level in the Mexican Social Security Institute. Salud Pública Méx 2006;48 (Suppl 1):S48–64. Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Genugten ML, Hoogenveen RT, Mulder I, et al. Future burden and costs of smoking-related disease in the Netherlands: a dynamic modeling approach. Value Health 2003;6:494–9. 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.64157.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Potapchik E, Popovich L. Social cost of substance abuse in Russia. Value in Health Regional 2014;4:1–5. 10.1016/j.vhri.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Quah E, Tan KC, Saw SL, et al. The social cost of smoking in Singapore. Singapore Med J 2002;43:340–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kang HY, Kim HJ, Park TK, et al. Economic burden of smoking in Korea. Tob Control 2003;12:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bolin K, Borgman B, Gip C, et al. Current and future avoidable cost of smoking—estimates for Sweden 2007. Health Policy 2011;103:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Priez F, Jeanrenaud C, Vitale S, et al. The social cost of tobacco in Switzerland. Switzerland: IRER—University of Neuchâtel, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Leartsakulpanitch J, Nganthavee W, Salole E. The economic burden of smoking-related disease in Thailand: a prevalence-based analysis. J Med Assoc Thai 2007;90:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Allender S, Balakrishnan R, Scarborough P, et al. The burden of smoking-related ill health in the UK. Tob Control 2009;18:262–7. 10.1136/tc.2008.026294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scarborough P, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, et al. The economic burden of ill health due to diet, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol and obesity in the UK: an update to 2006–07 NHS costs. J Public Health 2011;33:527–35. 10.1093/pubmed/fdr033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs--United States, 1995–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51:300–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xu X, Bishop EE, Kennedy SM, et al. Annual Healthcare Spending Attributable to Cigarette Smoking—an update. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:326–33. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoang Anh P, Thu L, Ross H, et al. Direct and indirect costs of smoking in Vietnam. Tob Control 2014;0:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ross H, Vu Trung D, Xuan Phu V. The cost of smoking in Vietnam: the case of inpatient care. Tob C ontrol 2007;16:405–9. 10.1136/tc.2007.020396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. WHO. WHO global report: mortality attributable to tobacco. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.http://www.who.int/gho/health_financing/en/ WHO Global Health Expenditure database accessed online 1 September 2015.

- 49. Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, et al. Mortality from tobacco in developing countries: indirect estimation from national vital statistics. Lancet 1992;339:1268–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/ WHO Global Burden of Disease data accessed online 8 May 2015.

- 51.http://data.worldbank.org/products/wdi World Bank Group World Development Indicators data accessed online 25 May 2015.

- 52.http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/weodata/index.aspx IMF World Economic Outlook April 2015 update accessed online 25 May 2015.

- 53. WHO. WHO guide to cost effectiveness analysis. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Oberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, et al. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet 2011;377:139–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Feirman SP, Glasser AM, Teplitskaya L, et al. Medical costs and quality-adjusted life years associated with smoking: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2016;16:646 10.1186/s12889-016-3319-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FF, van Ineveld BM, et al. The friction cost method for measuring indirect costs of disease. J Health Econ 1995;14:171–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Viscusi W, Aldy J. The Value of a Statistical Life: A Critical Review of Market Estimates Throughout the World. Harvard Law School John M. Olin Center for Law, Economics and Business Discussion Paper Series. Paper 392. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

tobaccocontrol-2016-053305supp001.pdf (367.4KB, pdf)