Abstract

Background

Lower extremity muscle weakness is a primary contributor to post-stroke dysfunction. Resistance training is an effective treatment for hemiparetic weakness and improves walking performance. Post-stroke subject characteristics that do or do not improve walking speed following resistance training are unknown.

Objective

The purpose of this paper was to describe baseline characteristics, as well as responses to training, associated with achieving a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in walking speed (≥0.16 m/s) following Post-stroke Optimization of Walking Using Explosive Resistance (POWER) training.

Methods

Seventeen participants completed 24 sessions of POWER training, which included intensive progressive leg presses, jump training, calf raises, sit-to-stands, step-ups, and over ground fast walking. Outcomes included SSWS, FCWS, DGI, FMA-LE, 6-MWT, paretic knee power, non-paretic knee power, and paretic step ratio.

Results

Specific to those who reached MCID in SSWS (e.g. “responders”), significant improvements in SSWS, FCWS, 6-MWT, paretic knee power, and non-paretic knee power was realized. Paretic knee power and non-paretic knee power significantly improved in those who did not achieve MCID for gait speed (e.g. “non-responders”).

Conclusion

The potential for POWER training to enhance general locomotor function was confirmed. Baseline paretic knee strength/power may be an important factor in how an individual responds to this style of training. The lack of change within the non-responders emphasizes the contribution of factors other than lower extremity muscle power improvement to locomotor dysfunction.

Keywords: Stroke, exercise, gait, strength training, power training

Introduction

Post-stroke muscle weakness is in part due to primary damage caused by the stroke, as well as secondary changes due to immobility and physical inactivity.1,2 Primary weakness post-stroke is the result of diminished signal transmission along descending neural pathways causing a loss in voluntary activation.2–4 Alterations in muscle structure and function following stroke are among the secondary changes that contribute to weakness and are evident by muscle atrophy and fiber-type transformations caused in large part by sedentary behaviors.5–7 Post-stroke weakness translates to locomotor disturbances and contributes to approximately 65% of individuals with stroke who are unable to ambulate independently and efficiently about their homes and communities.8–10

Following stroke, a frequent locomotor impairment observed is slow walking speed. Improving gait and gait-related activities post-stroke is the most often stated goal during rehabilitation.11–13 There exists a variety of intervention approaches designed to improve post-stroke walking, including aerobic exercise training,14,15 functional electrical stimulation.16 treadmill walking with or without body weight support,17–19 biofeedback therapy,20 and progressive strength training.21,22 However, a critical review of post-stroke walking rehabilitation interventions found no differences in post-treatment self-selected walking speed (SSWS) changes across widely used rehabilitation modalities.23 This lack of superiority amongst intervention approaches may reflect the heterogeneity of the post-stroke population and the various deficits that likely contribute to post-stroke walking dysfunction. Thus, we are left to speculate on what determines whether a given individual will or will not “respond” to a given intervention.

The purpose of the initial study was to examine the effects of Post-stroke Optimization of Walking Using Explosive Resistance (POWER) training, a high-intensity and high-velocity lower limb power training program, on post-stroke muscular and locomotor function.21,24 To better understand which individuals respond to this type of training, our interest in the current study was in analyzing subgroups of “responders” and “non-responders” to this training intervention. Specifically, the purpose of this paper was to determine baseline and training response differences in individuals who achieved a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of ≥0.16 m/s in walking speed to those who achieved only minimal gains following POWER training.

Methods

Participants

Seventeen individuals with chronic (≥6 months) post-stroke hemiparesis who completed the POWER training intervention were included in analysis. Two subjects were withdrawn from the initial study due to a previous injury not due to training and work commitments. For subjects to be considered for data analysis, all training sessions had to be completed within a maximum of 14 weeks from the initial training session. Subjects were recruited from May of 2012 to August of 2016. Inclusion criteria for training were: (1) age 18–70, (2) residual paresis in the lower extremity (Fugl-Myer Lower Extremity score <34), (3) ability to walk without support from another person for 100 feet and (4) a self-selected walking speed (SSWS) <1.0 m/s. Subjects were excluded if they have experienced: (1) intermittent claudication while walking, (2) severe arthritis or other impairments from previous injuries in the hip, knee, or ankle that limit range of motion, (3) history of congestive heart failure, unstable cardiac arrhythmias, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, severe aortic stenosis, COPD, angina or dyspnea at rest or during ADL’s, (4) previous or concurrent neurological disorders or major head trauma, (5) severe visual impairments, and (6) severe hypertension with systolic >200 mm Hg and diastolic >110 mm Hg at rest. As suggested by the American Heart Association’s physical activity and exercise recommendations,25 all subjects who met criteria completed an exercise tolerance test and were cleared for participation by the study cardiologist. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to participation and all aspects of this study were performed in accordance with the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina.

Training intervention

The POWER training program included 24 sessions (2–3 sessions/ wk for up to 12 wks). Bilateral and unilateral lower extremity exercises were performed, along with task specific exercises. To emphasize muscle power production during training subjects were instructed to perform the concentric phase of each exercise as quickly as possible with a slow controlled eccentric phase. Before training, 1-repetition maximum (1RM) was found for the leg press and jump training exercises. The modified version of 10-RM was used to find a predicted 1RM, which requires individuals to perform the exercise at a weight that only 10 repetitions could be completed. Once individuals could complete all sets and repetitions without rest the exercises progressed (e.g. increase weight, increase step height, weighted vest, etc.). Three sets of 20 repetitions were always performed unless otherwise stated. If a weight vest was used the initial weight was set to 5% of bodyweight and increased by 5% for each progression.

Each session before training individuals warmed up for 5 min on a NuStep® T5XR Recumbent Cross Trainer (NuStep Inc.; Ann Arbor, MI) or Monark recumbent cycle ergometer (Monark Exercise AB; Vansbro, Sweden), as well as performing 20 repetitions of bilateral leg press at 20% of 1RM. Leg press, jumping, and calf raises were performed on a supine exercise device (Jump Trainer; Shuttle MVP Pro, Shuttle System Inc: Glacier, Washington, Figure 1). Leg presses started at 3 sets of 20 repetitions with a reduction in repetitions by 5 every 6 sessions, therefore final sessions were 3 sets of 5 repetitions. Training load was increased by 10% when repetitions decreased. Training began with double limb jumps and progressed to single limb jumps by week 4. Load was increased by 10% when all sets and repetitions were completed without rest. Calf raises were initially performed on the jump trainer and progressed to upright with wall support to upright without wall support to a step. Each training position began with double limb support and progressing to single limb support before moving on to the next training position (e.g. jump training, upright without wall support). Sit-to-stands were initially performed at a higher chair with bodyweight and progressed to a lower chair with bodyweight to a lower chair with weight vest. Step-ups were initially performed at a lower step and step height was progressively increased. When max step height was reached a weight vest was added. To emphasize task specific power generation participants completed 10 m of fast walking training (10 trials/session; 3 trials forward, 3 trial backward, and 2 trials lateral) at 125% of overground SSWS. Individual trials were timed to ensure speed was met.

Figure 1.

Stroke participant on a Jump Trainer.

Clinical outcome measures

The Fugl-Meyer Lower Extremity Assessment (FMA-LE) was an indicator of lower extremity motor recovery.26 The Dynamic Gait Index (DGI) measured both general and task-specific balance and functional mobility, as well as fall risk.27 Walking endurance was assessed by the 6-min walking test (6-MWT).28 Licensed physical therapists performed all clinical assessments.

Lower extremity muscle power

Muscle power generation was assessed using a dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems Inc; Shirley, New York). Prior to testing each subject was allowed a period of familiarization and warm-up. Subjects were positioned on the dynamometer and the axis of the dynamometer aligned with the knee joint axis of rotation. First, maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) was determined in the paretic and non-paretic knee extensor muscle groups. Individuals performed three rounds (3 trials each round) of isometric contractions: (1) 50% of MVIC, (2) 75% of MVIC, and (3) 100% of MVIC. Secondly, peak isotonic power was assessed in the paretic and non-paretic knee extensor muscle groups using an external resistance set at approximately 40% of MVIC. This criterion was used because differences in lower limb maximal velocity occur at relatively low external forces and are most closely associated with gait velocity in older individuals.21,29 Peak isotonic paretic (PKP) and non-paretic knee power (NPKP) were normalized to bodyweight (kg) for data analysis.

Overground walking

Subjects walked on a 20 ft-long gait mat (GAITRite, CIR Systems Inc; Sparta, New Jersey) to measure self-selected walking speed (SSWS) and fastest comfortable walking speed (FCWS).30 Three trials at each speed were performed with data averaged for analyses. Paretic step ratio (PSR), calculated from the GAITRite, is a biomechanical marker that represents the percentage of stride length accounted for by the paretic step and was used to assess walking-specific motor control and is expressed as a percentage.31,32 PSR was calculated using the equation: Paretic step length/(Paretic + Non-paretic step length). PSR reflects the degree of step length asymmetry, which is a good indicator of walking impairment in hemiparetic individuals with changes towards a more symmetric pattern correlating with faster and more efficient walking. PSR is reported as the absolute value of the deviation from the symmetrical value of 0.5.32

Data analysis

Data were analyzed for the entire sample, as well as by responder and non-responder groups, based on the magnitude of response to the intervention defined by the change in SSWS. Participants were placed in the responder group if they had a change score from baseline to post training of ≥0.16 m/s in SSWS. The value of ≥0.16 m/s has been previously determined as the MCID in post-stroke subjects and individuals who meet this criteria are more likely to experience improvement in disability level.33 For continuous variables (SSWS, FCWS, 6-MWT, PKP, NPKP, and PSR), a 2-tailed independent sample t-test was used to test for differences between the responder and non-responder groups at baseline. Paired sample t-tests were used to test for within-group differences in pre- versus post-training outcomes. For discrete variables (DGI and FMA-LE), the Mann-Whitney U test compared responders to non-responders at baseline, and the Wilcoxon signed rank test compared pre- vs. post-training values. Correlations were only run between primary outcomes of power (PKP and NPKP) and locomotion measures (SSWS, FCWS, and 6MWT). Baseline correlations, baseline correlations with change scores, and change score correlations for outcomes were determined by Pearson’s correlational coefficients. Only moderate (r = 0.45) or higher correlations are reported.

Results

Participants

There were 10 subjects identified as responders and seven as non-responders. Responders included 5 males, 5 with left hemiparesis, and a mean age of 43.70 ± 18.3 years (range 19–66). Non-responders included 5 males, 4 with left hemiparesis, and a mean age of 54.71 ± 11.7 (range 33–66). There were no significant differences between groups at baseline for demographics (age, gender, hemiparetic side). There were no significant differences between groups at baseline for clinical outcomes except for the 6-MWT (difference of 497.00 ± 416.1; p = 0.04), with responders being able to significantly walking further at baseline. However, PKP (p = 0.05) was right at the cut-off of <0.05 significance.

For the entire sample (n = 17), SSWS increased by 0.17 ± 0.2 m/s, which is both statistically significant (p = 0.001) and clinically meaningful. FCWS (p = 0.02), 6-MWT (p = 0.02), paretic knee power (p < 0.0001) and non-paretic knee power (p < 0.0001) all improved significantly from baseline to post-training (Table 1). The responder group significantly improved SSWS (0.28 ± 0.1 m/s), FCWS (0.31 ± 0.2), 6-MWT (153.52 ± 173.6), PKP (17.89 ± 11.1) and NPKP (65.36 ± 43.2). The non-responder group significantly improved PKP (p = 0.008) and NPKP (p = 0.02) following training (Table 2).

Table 1.

Pre- and post-training values for entire sample (n = 17).

| Pre | Post | |

|---|---|---|

| SSWS (m/s) | 0.46 ± 0.3 | 0.63 ± 0.4* |

| FCWS (m/s) | 0.70 ± 0.6 | 0.90 ± 0.6* |

| DGI | 13.69 ± 4.2 | 13.44 ± 4.5 |

| FMA-LE | 17.81 ± 5.7 | 18.88 ± 7.3 |

| 6-MWT (ft.) | 624.39 ± 476.0 | 730.92 ± 473.3* |

| PKP (V*Nm/kg) | 51.27 ± 46.5 | 64.25 ± 46.0* |

| NPKP (V*Nm/kg) | 152.83 ± 64.5 | 219.04 ± 71.5* |

| PSR | 0.10 ± 0.1 | 0.10 ± 0.1 |

Indicates a significant improvement from pre to post training (p < 0.05) for entire sample.

SSWS, Self-selected walking speed; FCWS, Fastest comfortable walking speed; DGI, Dynamic Gait Index; FMA-LE, Fugl-Myer Lower Extremity Assessment; 6-MWT, 6-min walk test; PKP, paretic knee power; NPKP, non-paretic knee power; and PSR, paretic strep ratio.

Table 2.

Pre- and post-training values for responder (n = 10) and nonresponders (n = 7) groups.

| Responder | Non-responder | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| SSWS (m/s) | 0.55 ± 0.3 | 0.84 ± 0.4* | 0.34 ± 0.3 | 0.34 ± 0.2 |

| FCWS (m/s) | 0.83 ± 0.5 | 1.14 ± 0.5* | 0.51 ± 0.6 | 0.54 ± 0.5 |

| DGI | 14.56 ± 4.5 | 14.89 ± 4.3 | 12.57 ± 3.8 | 11.57 ± 4.4 |

| FMA-LE | 19.56 ± 5.4 | 20.56 ± 6.1 | 15.57 ± 5.7 | 16.71 ± 8.7 |

| 6-MWT (ft.) | 856.31 ± 507.6 | 1009.83 ± 435.3* | 359.34± 273.0 | 412.16 ± 281.8 |

| PKP (V*Nm/kg) | 68.18 ± 50.4 | 86.07 ± 45.5* | 27.10 ± 28.4 | 33.07 ± 24.7* |

| NPKP (V*Nm/kg) | 157.53±67.1 | 222.89±75.8* | 146.11 ± 65.2 | 213.53 ± 70.4* |

| PSR | 0.08 ± 0.1 | 0.08 ± 0.1 | 0.13 ± 0.1 | 0.13 ± 0.1 |

Indicates a significant difference from pre- to post-training (p < 0.05) for responder and non-responder groups.

SSWS, Self-selected walking speed; FCWS, Fastest comfortable walking speed; DGI, Dynamic Gait Index; FMA-LE, Fugl-Myer Lower Extremity Assessment; 6-MWT, 6-min walk test; PKP, paretic knee power; NPKP, non-paretic knee power; and PSR, paretic strep ratio.

Baseline correlations

For the entire sample, baseline PKP correlations show a moderate/strong positive relationship with baseline SSWS (r = 0.60), FCWS (r = 0.63), and NPKP (r = 0.57), as well as a strong positive correlation with baseline 6-MWT (r = 0.75). These results suggest that paretic power has a strong relationship with non-paretic power and locomotor performance. In the responder group, baseline associations were the same as seen in the whole sample. PKP had moderate/strong correlations with SSWS (r = 0.64) and NPKP (r = 0.64), as well as strong correlations with FCWS (r = 0.75) and 6-MWT (r = 0.76), however, in the non-responder group the only association was between PKP and NPKP (r = 0.54).

Baseline correlations with change scores

For the entire sample, baseline PKP showed a moderate/strong positive correlation with a change in SSWS (r = 0.58), however, this did not hold true for NPKP. Baseline SSWS, FCWS, and 6-MWT speed and distance did not correlate with changes in PKP or NPKP. In the responder group, baseline PKP had a moderate positive associated with a change in SSWS (r = 0.51) and a negative associated with a change in PKP (r = −0.53), as well as a negative moderate correlation between baseline NPKP and a change in PKP (r = −0.47). Within the non-responder group, PKP had a strong negative association with a change in PKP (r = −0.70) and NPKP had a strong positive correlation with a change in SSWS (r = 0.72). For baseline SSWS, no correlations were seen with PKP or NPKP in the responder group, however a moderate/strong negative association was seen with a change in PKP (r = −0.59) in the non-responder group. For baseline FCWS, no correlations were seen in the responder group, however there was a moderate/strong negative association was seen with a change in PKP (r = −0.67) in the non-responder group. For baseline 6-MWT, a moderate/strong negative correlation was found with a change in PKP (r = −0.62) in the responder group as well as in the non-responder group (r = −0.67).

Change score correlations

The only correlation between PKP or NPKP changes with locomotor changes was a moderate correlation between PKP and 6-MWT (r = 0.51). Within the responder group, a change in PKP had a moderate positive correlation with a change in 6-MWT (r = 0.47) and a strong positive correlation with a change in NPKP (r = 0.73). In the non-responder group, a change in NPKP had a moderate negative correlation with a change in 6-MWT (r = −0.46).

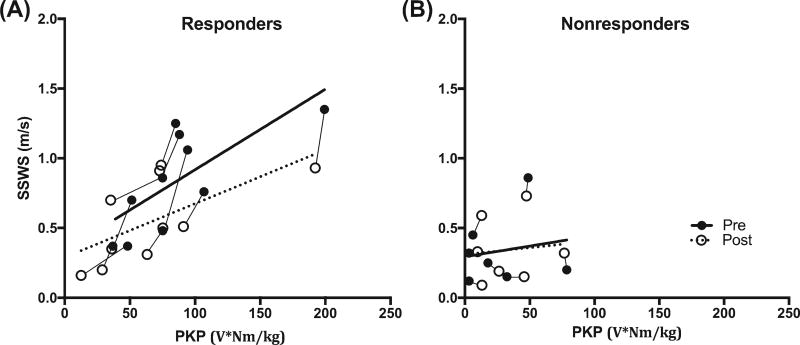

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between SSWS and PKP in responders (panel A) and non-responders (panel B). Fit lines for pre and post-training time points show the positive relationship between SSWS and PKP in responder group while this relationship is not evident in non-responders. In addition, the increase in post-training SSWS and PKP is also apparent in responders compared to non-responders.

Figure 2.

Each line is a single subject in the responder group (panel A) and non-responder group (panel B). Pre-training (solid circles) and post-training (non-solid circles) individual subject results of paretic knee power (PKP) plotted against self-selected walking speed (SSWS). Dotted line is the fit line for pre-training and solid line is fit line for post-training.

Discussion

Subjects with chronic stroke who underwent 24 sessions of POWER training showed statistically significant improvements in SSWS, FCWS, 6-MWT, paretic and non-paretic knee power post-training. When focusing on the individuals that met the MCID for SSWS, the same variables significantly improved, however improvements in “non-responders” were limited to muscle function outcomes (i.e. muscle power generation).

Often times resistance training and power training are used interchangeably, however there is a distinct difference between these two training methodologies. Resistance training is defined as an activity that is designed to improve muscular fitness by exercising a muscle or muscle group against external resistance. Power training falls under the umbrella term of strength training but has a specific definition of an activity that is designed to improve muscular fitness by developing a muscle or muscle group’s ability to contract at maximum force in minimal time.34 The majority of rehabilitation research has focused on traditional resistance training in individuals post-stroke,22,35–37 with only one other study focusing on power training.21,38 Therefore, it is difficult to compare our results to previous studies, however comparisons have been made to higher intensity resistance training programs and the one study found that focuses on the time component needed for proper power training.

Resistance training research that assessed locomotor performance in individuals with chronic stroke has shown limited effects. Ouellette et al.22 trained individuals at 70% of 1RM, which is considered a high-intensity intervention. Individuals performed 3 sets of 8–10 repetitions of leg press, unilateral knee extension, unilateral ankle dorsiflexion, and plantarflexion with training intensity adjusted biweekly by reassessing 1RM. The progressive training group significantly improved strength in all muscle groups tested with the exception of the non-paretic ankle dorsiflexors. Strength in the knee extensors improved by 31.4% in the paretic limb and 38.2% in the non-paretic limb. Additionally, peak power increased 33% for paretic and 28.5% for non-paretic knee extensors. However, in contrast to our results SSWS, FCWS, and 6-MWT did not significantly improve after a 12-week intervention. Another 12-wk high-intensity strength training intervention by Weiss et al.37 had individuals perform standing hip flexion, abduction, and extension, as well as sitting knee extension and leg press using 3 sets of 8–10 repetitions. All muscle groups significantly improved strength except the hip extensors with a 64% gain in paretic strength and 70% gain in non-paretic strength in the knee extensors. SSWS did not significantly improve in this study and the other functional outcomes were not assessed. To our knowledge only one other study focused on the speed component of training and assessed locomotor outcomes. Hill et al.38 trained individuals 3×/wk for 8-wks and completed 4 sets of 4 repetitions unilaterally at 85–95% of 1RM for both leg press and plantarflexion. Individuals were encouraged to focus on explosive concentric movement and controlled eccentric movement such that the time of each phase was a ratio of 1:2. Post-training results showed a significant improvement in strength by 54% in the paretic and 57% in non-paretic limbs. Additionally, significant improvements were seen in the 6-MWT, unfortunately neither muscle power generation nor walking speeds were assessed.

After separating individuals in our cohort into responder and non-responder groups based on changes in SSWS, responders significantly improved walking and muscle power generation outcomes while non-responders only improved muscle power generation (PKP and NPKP). The significant improvements in PKP and NPKP are important as proof-of-principle for this intervention, thus allowing interpretation of other outcomes relative to improvements in muscle function following training. In responders, baseline PKP correlated with baseline SSWS and FCWS. Interestingly, in the non-responder group, no baseline correlations between muscle power generation and walking function were found. Kim & Eng39 previously reported that neither paretic nor non-paretic knee extensor torque was associated with SSWS. In contrast, Davies et al.,40 Bohannon et al.,41 and Nakamura et al.42 suggest that paretic knee extensor muscle function correlates with walking speed post-stroke. Our data extend on these results to muscle power generation and their association with locomotor function as our results agree with Davies et al.,40 Bohannon et al.,41 and Nakamura et al.42 that paretic knee extensors may be an important factor in locomotor function and improvement in locomotor function, but non-paretic knee extensor power may not be a limiting factor.

Our findings show a positive association between baseline PKP and gains in SSWS for the entire sample, suggesting improvements in locomotor performance may be dependent on baseline power. However, when the sample is separated into subgroups, the association between baseline PKP and changes in SSWS was found only in the responder group. In the non-responder group, baseline NPKP was associated with changes in SSWS. PKP was significantly less at baseline in non-responders, thus the possibility exists that a certain level of muscle power generation must be present for improvements in paretic muscle function to drive changes in functional performance.

Another potentially important factor to consider when describing post-stroke walking performance is walking endurance. At baseline there was a significant difference between responders and non-responders for 6-MWT, with responders walking further prior to training despite almost identical overground walking speeds. Notwithstanding greater baseline performance, the responder group significantly improved walking distance following training. In contrast, non-responders did not improve walking endurance post-training (i.e. 6-MWT). Similar to SSWS, changes in 6-MWT were positively correlated with PKP at baseline for the responder group only. Additionally, changes in PKP were associated with changes in 6-MWT. These results are supported by Patterson et al.43 and Pang et al.44 who suggest that a predictive factor for walking endurance is knee extension strength of the paretic leg.

Being able to identify if an individual will “respond” to a given intervention would be extremely valuable for clinical decision-making. Whether guided by baseline assessments or identification of mechanisms of change, information that can help rehabilitation professionals optimize outcomes is a critical goal for optimizing post-stroke locomotor recovery. Although the only baseline differences between responders and non-responders was the 6-MWT in the current study, the lack of any improvement in locomotor outcomes in the non-responder group suggests the potential for early identification of responders based on these outcomes. Importantly, this lack of change in locomotor function in the non-responders, despite significant improvements in muscle function, highlights the possible contribution of factors other than lower extremity muscle power generation to locomotor dysfunction in some subjects. Future work should focus on the time course of changes in walking function for responders so as to identify early on those subjects who are/are not appropriate for this type of intervention. In addition, in depth neuromechanical analyses of walking (e.g. kinematics, kinetics and EMG) may provide more insight as to why and how certain subjects respond to this type of training.

The focus of this manuscript was to analyze data from a previously completed study to assess justification for further study of strength/power as a potential limiting factor in increasing walking speed by comparing “responder” and “non-responders.” This type of analysis is often neglected, however it is extremely important because it focuses in on the principle of individual differences in exercise physiology that states all individuals will not respond similarly to a given training stimulus.45 Clinicians will encounter high and low responders due to potentially limiting factors and it is important to identify an individual early on what intervention style they will respond to best. Researchers most often report group mean changes and conclusions are based upon these results; suggesting an effective or ineffective intervention. Rarely are studies separating cohorts into subgroups, such as responder and non-responders or young and older, to determine how the interventions impacted different types of individuals.

Limitations

The results of this study are somewhat limited by the sample size in each group, which restricts the ability to predict the changes in walking speed following POWER training. In addition, the different elements included in POWER training (high-velocity resistance training and fast walking) limit conclusions as to their independent contribution to improvements in muscular function and walking speed seen in the responder group. Knowing the independent contributions of these activities to walking performance will improve individualize training interventions. Next, our walking outcomes were limited to walking speed and distance, thus we may have potentially missed other functional gains that might result from enhancing lower extremity muscle power generation. Finally, analyses of muscle power generation were limited to the paretic and non-paretic knee extensor muscle groups. Data for other lower extremity muscle groups (e.g. ankle plantar flexor/dorsi flexor and hip flexor/extensor) may prove valuable in similar analyses.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate clinical outcomes in an effort to differentiate individuals who do or do not respond to this type of training intervention. Of the subjects who meet criteria for MCID in walking speed (e.g. “responders”), significant improvements in SSWS, FCWS, 6-MWT, and muscular power of both the paretic and non-paretic limbs were realized, while non-responders only significantly improved paretic and non-paretic muscle power generation. Baseline correlations showed that paretic knee power was associated with walking speed and endurance. Additionally, baseline paretic knee power, but not non-paretic knee power, was associated with changes in locomotor outcomes. These findings suggest the potential importance of lower extremity muscle power, especially in the paretic limb, on walking speed and distance. Targeting outcomes that predict treatment success could lead to better outcomes and a more individualized treatment plan.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the American Heart Association [grant number 11BGIA7450016]; and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs [grant number RR&D I01 RX000844].

Abbreviations

- 6-MWT

6-min walk test

- DGI

Dynamic Gait Index

- FCWS

fastest comfortable walking speed

- FMA-LE

Fugl-Myer Lower Extremity Assessment

- MCID

minimal clinically important difference

- MVIC

maximum voluntary isometric contraction

- NPKP

non-paretic knee power

- PKP

paretic knee power

- PSR

paretic step ratio

- POWER

Post-stroke Optimization of Walking using Explosive Resistance

- SSWS

self-selected walking speed

References

- 1.Signal NE. Strength training after stroke: Rationale, evidence and potential implementation barriers for physiotherapists. N Zeal J Physiotherapy. 2014;42:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teixeira-Salmela LF, Olney SJ, Nadeau S, Brouwer B. Muscle strengthening and physical conditioning to reduce impairment and disability in chronic stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(10):1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris ML, Polkey MI, Bath PM, Moxham J. Quadriceps muscle weakness following acute hemiplegic stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15(3):274–281. doi: 10.1191/026921501669958740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newham DJ, Hsiao SF. Knee muscle isometric strength, voluntary activation and antagonist co-contraction in the first six months after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(9):379–386. doi: 10.1080/0963828001006656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jorgensen L, Jacobsen BK. Changes in muscle mass, fat mass, and bone mineral content in the legs after stroke: A 1 year prospective study. Bone. 2001;28(6):655–659. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metoki N, Sato Y, Satoh K, Okumura K, Iwamoto J. Muscular atrophy in the hemiplegic thigh in patients after stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82(11):862–865. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000091988.20916.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunnerhagen KS, Svantesson U, Lonn L, Krotkiewski M, Grimby G. Upper motor neuron lesions: Their effect on muscle performance and appearance in stroke patients with minor motor impairment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(2):155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perry J, Garrett M, Gronley JK, Mulroy SJ. Classification of walking handicap in the stroke population. Stroke. 1995;26(6):982–989. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyaert C, Vasa R, Frykberg GE. Gait post-stroke: Pathophysiology and rehabilitation strategies. Neurophysiol Clin = Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;45(4–5):335–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alguren B, Lundgren-Nilsson A, Sunnerhagen KS. Functioning of stroke survivors – a validation of the ICF core set for stroke in Sweden. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(7):551–559. doi: 10.3109/09638280903186335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris JE, Eng JJ. Goal priorities identified through client-centred measurement in individuals with chronic stroke. Physiother Canada. 2004;56(3):171–176. doi: 10.2310/6640.2004.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirschberg GG. Ambulation and self-care are goals of rehabilitation after stroke. Geriatrics. 1976;31(5):61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohannon RW, Andrews AW, Smith MB. Rehabilitation goals of patients with hemiplegia. Int J Rehabil Res. 1988;11(2):181–183. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MJ, Kilbreath SL, Singh MF, Zeman B, Lord SR, Raymond J, et al. Comparison of effect of aerobic cycle training and progressive resistance training on walking ability after stroke: A randomized sham exercise-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):976–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macko RF, DeSouza CA, Tretter LD, Silver KH, Smith GV, Anderson PA, et al. Treadmill aerobic exercise training reduces the energy expenditure and cardiovascular demands of hemiparetic gait in chronic stroke patients. A preliminary report. Stroke. 1997;28(2):326–330. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCrimmon CM, King CE, Wang PT, Cramer SC, Nenadic Z, Do AH. Brain-controlled functional electrical stimulation therapy for gait rehabilitation after stroke: A safety study. J NeuroEng Rehabil. 2015;12:57. doi: 10.1186/s12984-015-0050-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YW, Moon SJ. Effects of treadmill training with the eyes closed on gait and balance ability of chronic stroke patients. J Phys Therapy Sci. 2015;27(9):2935–2938. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laufer Y, Dickstein R, Chefez Y, Marcovitz E. The effect of treadmill training on the ambulation of stroke survivors in the early stages of rehabilitation: A randomized study. J Rehabil Res Develop. 2001;38(1):69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hesse S, Werner C, Bardeleben A, Barbeau H. Body weight-supported treadmill training after stroke. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2001;3(4):287–294. doi: 10.1007/s11883-001-0021-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Del Din S, Bertoldo A, Sawacha Z, Jonsdottir J, Rabuffetti M, Cobelli C, et al. Assessment of biofeedback rehabilitation in post-stroke patients combining fMRI and gait analysis: A case study. J Neuro Eng Rehabil. 2014;11:53. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-11-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan P, Embry A, Perry L, Holthaus K, Gregory CM. Feasibility of lower-limb muscle power training to enhance locomotor function poststroke. J Rehabil Res Develop. 2015;52(1):77–84. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2014.04.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouellette MM, LeBrasseur NK, Bean JF, Phillips E, Stein J, Frontera WR, et al. High-intensity resistance training improves muscle strength, self-reported function, and disability in long-term stroke survivors. Stroke. 2004;35(6):1404–1409. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000127785.73065.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickstein R. Rehabilitation of gait speed after stroke: A critical review of intervention approaches. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22(6):649–660. doi: 10.1177/1545968308315997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunnicutt JL, Aaron SE, Embry AE, Cence B, Morgan P, Bowden MG, et al. The effects of POWER training in young and older adults after stroke. Stroke Res Treat. 2016;2016:7316250. doi: 10.1155/2016/7316250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Billinger SA, Arena R, Bernhardt J, Eng JJ, Franklin BA, Johnson CM, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2532–2553. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fugl-Meyer AR, Jaasko L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Steglind S. The poststroke hemiplegic patient. 1. A method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7(1):13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonsdottir J, Cattaneo D. Reliability and validity of the dynamic gait index in persons with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(11):1410–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fulk GD, Echternach JL, Nof L, O’Sullivan S. Clinometric properties of the six-minute walk test in individuals undergoing rehabilitation poststroke. Physiother Theory Pract. 2008;24(3):195–204. doi: 10.1080/09593980701588284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bean JF, Kiely DK, Herman S, Leveille SG, Mizer K, Frontera WR, et al. The relationship between leg power and physical performance in mobility-limited older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):461–467. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuys SS, Brauer SG, Ada L. Test-retest reliability of the GAITRite system in people with stroke undergoing rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(19–20):1848–1853. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.549895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balasubramanian CK, Bowden MG, Neptune RR, Kautz SA. Relationship between step length asymmetry and walking performance in subjects with chronic hemiparesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowden MG, Clark DJ, Kautz SA. Evaluation of abnormal synergy patterns poststroke: Relationship of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment to hemiparetic locomotion. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(4):328–337. doi: 10.1177/1545968309343215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tilson JK, Sullivan kJ, Cen SY, Rose DK, Koradia CH, Azen SP, et al. Meaningful gait speed improvement during the first 60 days poststroke: Minimal clinically important difference. Phys Ther. 2010;90(2):196–208. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swain DP, Brawner CA, Chambliss HO, Nagelkirk PR, Bayles MP, Swank AM, editors. ACSM’s resource manual for guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 7. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. Musculoskeletal Exercise Prescription; pp. 482–495. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivey FM, Prior SJ, Hafer-Macko CE, Katzel Li, Macko RF, Ryan AS. Strength training for skeletal muscle endurance after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovascu Dis. 2017;26(4):787–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flansbjer UB, Miller M, Downham D, Lexell J. Progressive resistance training after stroke: Effects on muscle strength, muscle tone, gait performance and perceived participation. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(1):42–48. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss A, Suzuki T, Bean J, Fielding RA. High intensity strength training improves strength and functional performance after stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79(4):369–376. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill TR, Gjellesvik TI, Moen PM, Torhaug T, Fimland MS, Helgerud J, et al. Maximal strength training enhances strength and functional performance in chronic stroke survivors. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91(5):393–400. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31824ad5b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim CM, Eng JJ. The relationship of lower-extremity muscle torque to locomotor performance in people with stroke. Phys Ther. 2003;83(1):49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davies JM, Mayston MJ, Newham DJ. Electrical and mechanical output of the knee muscles during isometric and isokinetic activity in stroke and healthy adults. Disabil Rehabil. 1996;18(2):83–90. doi: 10.3109/09638289609166022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bohannon RW, Andrews AW. Correlation of knee extensor muscle torque and spasticity with gait speed in patients with stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71(5):330–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakamura R, Hosokawa T, Tsuji I. Relationship of muscle strength for knee extension to walking capacity in patients with spastic hemiparesis. The Tohoku J Exp Med. 1985;145(3):335–340. doi: 10.1620/tjem.145.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patterson SL, Forrester LW, Rodgers MM, Ryan AS, Ivey FM, Sorkin JD, et al. Determinants of walking function after stroke: Differences by deficit severity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(1):115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pang MY, Eng JJ, Dawson AS. Relationship between ambulatory capacity and cardiorespiratory fitness in chronic stroke: Influence of stroke-specific impairments. Chest. 2005;127(2):495–501. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.2.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meendering J, Fountaine C. Cardiorespiratory fitness assessments and exercise programming for apparently health participants. In: Liguori G, Dwyer GB, Fitts TC, Lewis BL, editors. ACSM’s resources for the exercise physiologist. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. pp. 44–79. [Google Scholar]