Summary

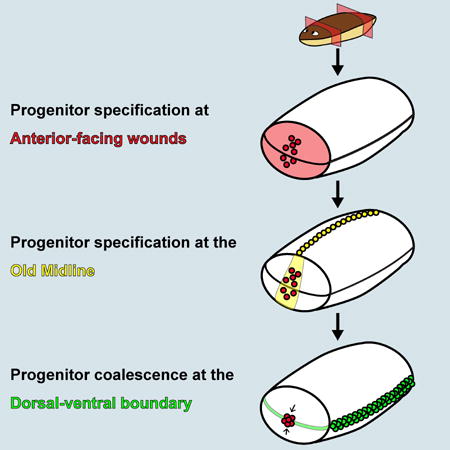

Regeneration in many organisms involves the formation of a blastema, which differentiates and organizes into the appropriate missing tissues. How blastema pattern is generated and integrated with pre-existing tissues is a central question in the field of regeneration. Planarians are free-living flatworms capable of rapidly regenerating from small body fragments [1]. A cell cluster at the anterior tip of planarian head blastemas (the anterior pole) is required for establishment of anterior-posterior (AP) and midline blastema pattern [2–4]. Transplantation of the head tip into tails induced host tissues to grow patterned head-like outgrowths containing a midline. Given the important patterning role of the anterior pole, understanding how it becomes localized during regeneration would help explain how wounds establish pattern in new tissue. Anterior pole progenitors were specified at the pre-existing midline of regenerating fragments, even when this location deviated from the medial-lateral (ML) median plane of the wound face. Anterior pole progenitors were specified broadly on the dorsal-ventral (DV) axis, and subsequently formed a cluster at the DV boundary of the animal. We propose that three landmarks of pre-existing tissue at wounds set the location of anterior pole formation – a polarized AP axis, the pre-existing midline, and the dorsal-ventral median plane. Subsequently, blastema pattern is organized around the anterior pole. This process, utilizing positional information in existing tissue at unpredictably shaped wounds, can influence patterning of new tissue in a manner that facilitates integration with pre-existing tissue in regeneration.

Graphical Abstract

Results and Discussion

Pattern formation during animal development can be initiated by symmetry-breaking mechanisms including asymmetric maternal factors in oocytes and the location of sperm entry [5,6]. Similar to development, animal regeneration requires mechanisms to establish tissue pattern, in tissue outgrowths called blastemas. However, tissue pattern establishment in blastemas must occur in the absence of embryonic pattern-initiating processes. Furthermore, regeneration has the additional challenge of integrating new tissue with existing tissue in the context of unpredictable injuries. An elegant solution to this challenge would be if pattern-initiating processes relied on cues present at the wound face. Planarians are a classic regenerative model system and are capable of regenerating from a large array of injuries, making them well suited to address the origins of pattern in blastemas. Planarian regeneration involves both blastema formation and the remodeling of pre-existing tissue [1], and requires proliferative cells (neoblasts) that include pluripotent stem cells [7].

Planarian head regeneration involves the formation of a cluster of specialized muscle cells at the anterior head tip called the anterior pole [2]. The anterior pole expresses notum [8], follistatin [9,10], and the transcription factors foxD [2,10] and zic-1 [3,4]. foxD [2] and zic-1 [3,4] are required for anterior pole formation through the specialization of neoblasts into anterior pole progenitors. foxD or zic-1 RNAi blocks pole regeneration and results in aberrant AP and ML patterning gene expression and absent or medially collapsed differentiated head tissues. These findings indicate a requirement for the anterior pole in AP and ML blastema patterning [2–4]. The planarian anterior pole has some similarities to other discrete regions of cells in developing embryos, such as the amphibian Spemann-Mangold organizer, that regulate patterning of neighboring tissue [2,3,11]. Therefore, the position of the regenerated anterior pole is likely critical to proper patterning, but how this positioning is controlled is poorly understood.

Tissue fragments containing the anterior pole can induce patterned outgrowths in host tissue following transplantation

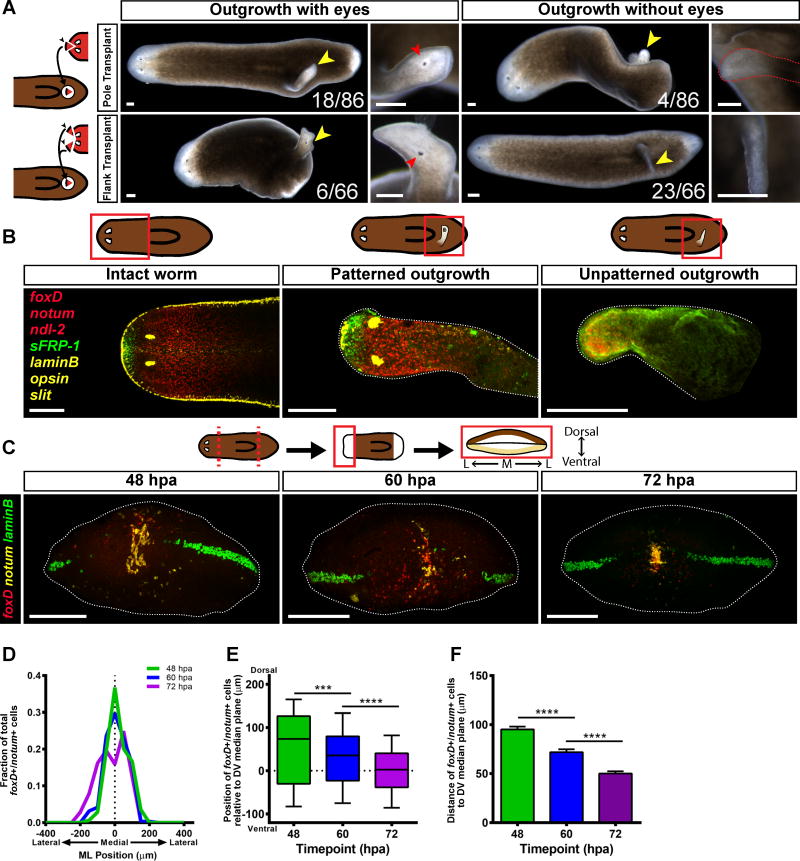

Transplantation was used to test the inductive capacities of the planarian head tip, which contains the anterior pole (“pole fragments”) (Figure 1A, Figure S1A–G). Donor animals were lethally irradiated to ablate all neoblasts [12]; any resultant outgrowth involving new cells would therefore be produced by host tissues in response to the transplant. As a control, we also transplanted equally sized head tip regions that were offset from the midline and lacking the anterior pole (“flank fragments”). Juxtaposition of different body regions causes outgrowths in planarians [13–17], and accordingly, both pole and flank transplants generated outgrowths (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Anterior pole progenitors are specified medially and in a broad DV domain.

(A) Live images of animals 14 days after pole or flank transplantation. Yellow arrowheads mark the site of an outgrowth. Red arrowheads mark an ectopic eye. (B) Animals were labeled using RNA FISH for the expression of foxD/notum (anterior pole), sFRP-1 (anterior head tip), slit (midline), ndl-2 (pre-pharyngeal region), opsin (photoreceptor neurons), and laminB (DV boundary). Merged images are displayed. For single-channel images see Figure S1H. The fact that some flank transplants triggered patterned outgrowths could reflect a less efficient but not absent complete head patterning potential of this region, or contaminating pole cells in some flank transplants. (A–B) Dorsal view, anterior is to the left. Scale bars, 200 μm. (C) Wild-type animals were subjected to a transverse amputation, fixed at 48, 60, and 72 hpa, and the expression of foxD (red), notum (yellow) and laminB (green) was analyzed by triple FISH. foxD+/notum+ cells appear around 48 hpa at the ML median plane of the anterior-facing wound, and accumulate over time near the DV median plane. Images shown are maximal intensity projections. Images are an en face view of the anterior blastema. Dorsal is up. Scale bars, 200 μm. (D) The distribution of the positions of foxD+/notum+ cells on the ML axis is centered roughly around the ML median plane of the fragment (dotted line). 48 hpa, n=18 worms; 60 hpa, n=24 worms; 72 hpa, n=18 worms. (E) The distribution of the positions of foxD+/notum+ cells on the DV axis becomes tighter and closer to the DV median plane over time. Data were compared with a Mann-Whitney test. 48 vs 60 hpa, ***p=0.0003, n>289 cells; 60 vs 72 hpa, ****p<0.0001, n>289 cells. (F) The distance between foxD+/notum+ cells and the DV median plane grows smaller over time. Data were compared using a Student’s t-test. 48 vs 60 hpa, ****p<0.0001, n>289 cells; 60 vs 72 hpa, ****p<0.0001, n>289 cells.

See also Figure S1 and Figure S2, as well as Movies S1 and S2.

Out of 86 “pole fragment” transplantations, 22 animals exhibited outgrowths, 18 of which possessed two eyes and were mobile (Figure 1A, Movie S1). Out of 66 “flank fragment” transplantations, 29 animals exhibited outgrowths, only six of which possessed eyes; the rest were immobile tissue spikes (Figure 1A, Movie S2). To assess patterning in these outgrowths, we performed fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) with RNA probes for foxD/notum (anterior pole), sFRP-1 (anterior head tip), slit (midline), ndl-2 (pre-pharyngeal region), opsin (photoreceptor neurons), and laminB (DV boundary). Pole transplant outgrowths with eyes (n = 8/8) and without eyes (n=3/4) displayed AP patterning and a midline (Figure 1B, S1H). These outgrowths displayed entirely dorsal identity and little dorsal-ventral boundary (n=4/4) (Figure S1I). Flank transplant outgrowths with eyes also had AP patterning and a midline (n = 6/6), whereas the spike outgrowths expressed only ndl-2 and no other anterior or midline markers (n = 8/8) (Figure 1B, S1H). Transplanted flank regions thus had less efficient but not absent potential to induce head pattern. Together with prior RNAi experiments that ablated the anterior pole, these data indicate an important role for cells at the anterior head tip in organizing head pattern. This motivated study of pole formation mechanisms to understand the logic by which head blastema pattern is formed and integrated with the pattern of pre-existing tissue.

Anterior pole progenitors are specified medially and in a broad DV domain

To understand pole positioning during regeneration, we first characterized anterior pole progenitor specification. Anterior pole progenitors are specified by expression of transcription factors such as foxD and zic-1 and appear medially at anterior-facing wounds [3,4,18]. The distribution of pole progenitors along the DV axis is poorly understood, so we imaged and quantified anterior pole progenitor specification in blastemas viewed en face (head-on) (Figure 1C, Figure S2A).

Pole progenitors were detected with foxD and notum expression. Because notum is also expressed in the brain [8,19], we examined only foxD/notum double-positive cells, which were present by 48 hours post amputation (hpa). These cells were centered at the ML median plane (midpoint between the right and left wound sides) from 48 hpa to 72 hpa (Figures 1C–D). The position of pole progenitors was quantified relative to the DV median plane (the midpoint between the dorsal and ventral sides) estimated using laminB expression (which marks the dorsal-ventral boundary [20]). foxD+/notum+ cells were initially dispersed on the DV axis (Figure 1C, Figure 1E). The distributions of these progenitors grew narrower and closer to the DV median plane with time, accumulating in a cluster by 72 hpa (Figure 1C, Figure 1E). Similarly, the average distance of anterior pole progenitors to the DV median plane grew smaller with time (Figure 1F). zic-1+/notum+ cells and follistatin+/notum+ cells displayed similar dynamics (Figures S2B–H).

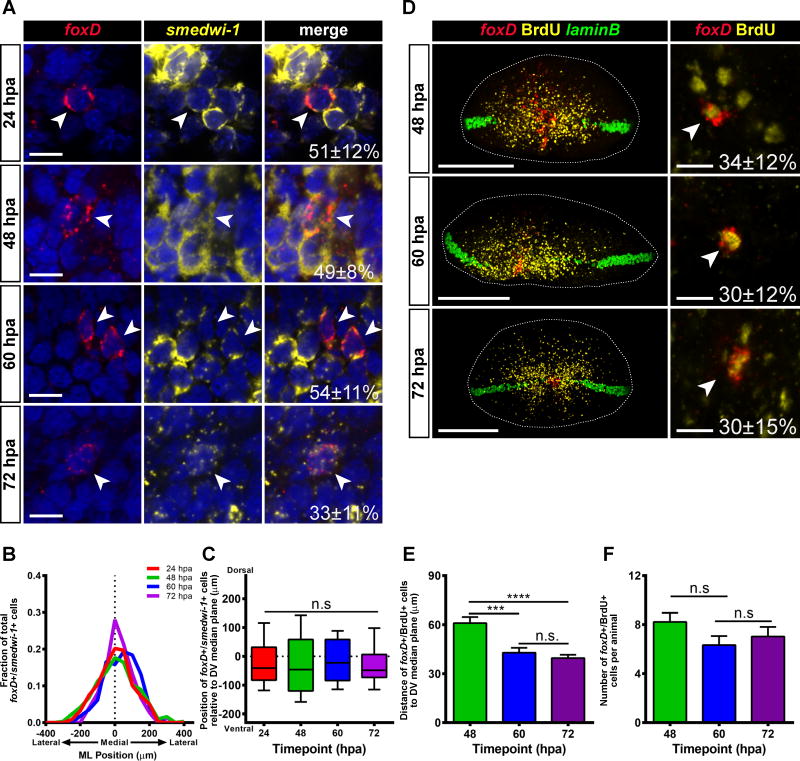

We hypothesized that the foxD+/notum+ cells include early stage anterior pole progenitors, which are the result of neoblast specialization. Irradiation depletes neoblasts (Figure S2J) and, consistent with previous reports [2,3], blocked formation of anterior pole progenitors and the pole (Figures S2K). To support the idea that the foxD+/notum+ cells observed were the result of neoblast specialization, animals were labeled with RNA probes to foxD and smedwi-1, which is a marker for neoblasts [26]. foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells were present from 24 to 72 hpa (Figure 2A) and were biased medially (Figure 2B), similar to foxD+/notum+ cells. However, the distributions of foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells along the DV axis did not become significantly narrower over time (Figure 2C) and the distance between the foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells and the DV median plane did not become smaller over time (Figure S2I). These results suggest that anterior pole progenitors are specialized from neoblasts at the ML median plane, but broadly along the DV axis, only accumulating at the DV median plane as post-mitotic progenitors.

Figure 2. Anterior pole progenitors are specified medially and in a broad DV domain.

(A) Wild-type animals were transversely amputated, fixed at 24, 48, 60 and 72 hpa, and expression of foxD (red) and smedwi-1 (yellow) was analyzed by triple FISH. Nuclear signal (DAPI) is shown in blue. A proportion of foxD+ cells were also smedwi-1+ at all timepoints examined (24 hpa, 51±21%; 48 hpa, 49±8%; 60 hpa, 54±11%; 72 hpa, 33±11%). (B) The distribution of the positions of foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells on the ML axis is centered roughly around the ML median plane of the fragment (dotted line). 24 hpa, n=29 worms; 48 hpa, n=19 worms; 60 hpa, n=8 worms; 72 hpa, n=8 worms. (C) The distribution of the positions of foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells on the DV axis does not significantly contract over time. The reference point for these coordinates is the DV median plane, which is estimated using laminB expression (dotted line). The box is defined by the first quartile, median, and third quartile, and the whiskers are defined by the 10th and 90th percentiles. Comparisons were made between all timepoints with a Kruskal-Wallis test. n.s. n>75 cells. (D) Wild-type animals were transversely amputated, pulsed for 2 hours in a BrdU solution, and then chased in 5g/L Instant Ocean. Animals were fixed at 48, 60 and 72 hpa, and expression of foxD (red), laminB (green) was analyzed by double FISH. Immunostaining for BrdU is shown in yellow. Left panel: foxD+/BrdU+ cells are scattered along the DV axis, and coalesce to a cluster with time. Right panel: Higher magnification image of a foxD+/BrdU+ cell. White arrowhead indicates cells double positive for foxD and BrdU. Percent of foxD+ cells which were also BrdU+ is displayed in the lower right corner of the merged image. (E) The distance between foxD+/BrdU+ cells and the DV median plane is smaller at 60 and 72 hpa than it is at 48 hpa. Data were compared using a Student’s t-test. 48 hpa vs 60 hpa, ***p=0.0007, n>114 cells; 48 hpa vs 72 hpa, ****p<0.0001, n>189 cells; 60 hpa vs 72 hpa, n.s., n>114 cells. (F) The number of foxD+/BrdU+ cells per animal is similar at all timepoints examined. Data were compared using a Student’s t-test. 48 hpa vs 60 hpa, n.s., n>18 animals; 60 hpa vs 72 hpa, n.s., n>18 animals. For the left panels of (D), images shown are maximal intensity projections. Images are an en face view of the anterior blastema. Dorsal is up. Scale bars, 200 μm. For (A) and right panels of (D), images shown are single confocal slices. Images are an en face view of the anterior blastema. Dorsal is up. Scale bars, 10 μm. For (E–F) data are represented as mean ± SEM.

See also Figure S2.

Anterior Pole Cells Coalesce at the DV Median Plane

Neoblast-derived progenitors have been observed to move from a specification location to their final destination for several tissue types, notably for the epidermis [21,22] and the eye [23,24]. To assess possible movement of dispersed pole progenitors along the DV axis into the anterior pole, we utilized bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling. BrdU is incorporated into neoblasts and can be used to trace the behavior of a cell cohort [25]. Animals were amputated, immediately BrdU-pulsed, and analyzed in a regeneration time course (Figure 2D). The average distance of foxD+/BrdU+ cells to the DV median plane was smaller at 60 and 72 hpa than at 48 hpa (Figure 2E), even as the number of foxD+/BrdU+ cells per animal remained relatively constant (Figure 2F). These results are consistent with net movement of pole progenitors from broadly dispersed on the DV axis into a coalesced anterior pole.

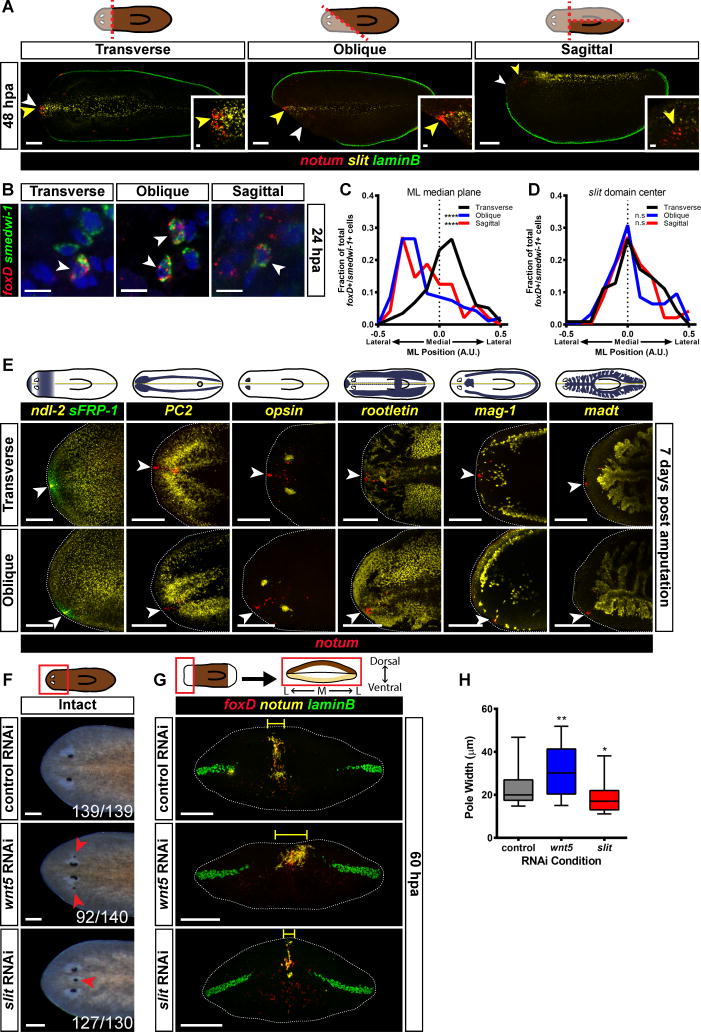

Anterior Pole Progenitor Specification Occurs at the Old Midline

Anterior pole progenitor specification could in principle occur either at the ML median plane of the wound, such as might be the case if the blastema involves de novo pattern organization, or at the midline of pre-existing tissue. To distinguish between these possibilities, animals were subjected to either transverse, oblique, or sagittal amputations, and the expression of notum, laminB, and slit (which marks the midline [26]) were examined. In transversely amputated animals, the anterior pole formed at the pre-existing midline (yellow arrowheads), which was coincident with the ML median plane of the anterior-facing wound (white arrowheads) (Figure 3A, Figure S3A). Strikingly, in the oblique and sagittal amputations, the anterior pole progenitors formed at the pre-existing midline, even though this point was far from the ML median plane of the wound. (Figure 3A, Figure S3A). Although the pole was shifted away from the ML median plane, with time these animals regenerated with the correct shape (Figure S3B). foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells (Figure 3B) were also shifted away from the ML median plane of the wound in oblique and sagittal fragments (Figure 3C). Instead, the pole-specialized neoblasts were present at the pre-existing slit+ midline, suggesting that the anterior pole progenitor specification zone is biased to be within the pre-existing midline (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Anterior pole formation occurs at the prior midline.

(A) Wild-type animals were subjected to either a transverse, oblique, or sagittal amputation, fixed at 48 hpa, and expression of notum (red), slit (yellow) and laminB (green) was analyzed by triple FISH. notum+ cells appear near the slit domain, even when that domain is no longer the middle of the wound face. Cartoon above shows type of injury; fully opaque region indicates the fragment selected for analysis. White arrowheads indicate the estimated ML median plane of the anterior-facing wound, and yellow arrowheads indicate the old midline, as marked by slit expression. Transverse 48 hpa, n=5/5; Oblique 48 hpa, n=10/10; Sagittal 48 hpa n=9/9. (B) Wild-type animals were subjected to either a transverse, oblique or sagittal amputation, fixed at 24 hpa, and expression of foxD (red) and smedwi-1 (green) was analyzed by double FISH. Nuclear signal (DAPI) is shown in blue. foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells could be found and quantified. Images are a single confocal slice. Images are an en face view of the anterior blastema. Dorsal is up. Scale bars, 10 μm. (C) Histogram of the coordinates of foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells along the medial-lateral axis. The reference point for these coordinates is the ML median plane of the wound face, which is marked with a dotted line on the graph. For transverse amputations the distribution of the positions of foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells is centered roughly around the ML median plane, whereas in oblique and sagittal fragments the peaks of the distributions are shifted away from this point. Data were compared using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test. Transverse vs Oblique ****p<0.0001 n>94 cells; Transverse vs Sagittal ****p<0.0001 n>48 cells. (D) Histogram of the coordinates of foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells along the medial-lateral axis. The reference point for these coordinates is the center of the slit expression domain, which is marked with a dotted line on the graph. The distribution of the positions of foxD+/smedwi-1+ cells is centered roughly around the middle of the slit expression domain. Data were compared using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test. Transverse vs Oblique n.s. n>94 cells; Transverse vs Sagittal n.s. n>48 cells. (E) Wild-type animals were subjected to either a transverse or oblique amputation as described in (A), fixed at 7 days following wounding, and expression of notum (red), and the following markers were analyzed by triple FISH: ndl-2 (yellow) and sFRP-1 (green); PC2 (yellow); opsin (yellow); rootletin (yellow); mag-1 (yellow); and madt (yellow). White arrowheads mark the position of the anterior pole. For clarity, ventral images (PC2) were vertically flipped to have the same orientation as dorsal images. The plane of symmetry for gene expression was centered at the position of the anterior pole, even in animals that had an asymmetric wound. (A, E) Images shown are maximal intensity projections. Dorsal view, anterior is to the left. Scale bars, 200 μm. For insets, scale bars are 20 μm. (F) Live images of control RNAi, wnt5(RNAi), and slit(RNAi) animals 28 days after the first RNAi feeding. wnt5(RNAi) animals displayed ectopic lateral eyes and slit(RNAi) animals displayed ectopic medial eyes. Number of animals with the phenotype is displayed in the lower right corner of each image. Red arrowheads indicate ectopic eyes. Anterior is to the left. Scale bars, 200 μm. (G) control RNAi, wnt5(RNAi), or slit(RNAi) animals were transversely amputated, fixed at 60 hpa, and expression of foxD (red), notum (yellow), and laminB (green) was analyzed by triple FISH. foxD+/notum+ cells occupied a wider area in wnt5(RNAi) animals, and a narrower area in slit(RNAi) animals, compared to control RNAi animals. The yellow bracket indicates the estimated pole width for the images shown. Images shown are maximal intensity projections. Images are an en face view of the anterior blastema. Dorsal is up. Scale bars, 200 μm. (H) Each animal was assigned a “pole width” score, which is the average distance of a cell to the center of its pole for that animal. wnt5(RNAi) animals had wider anterior poles and slit(RNAi) animals had narrower anterior poles. The box is defined by the first quartile, median, and third quartile, and the whiskers are defined by the 10th and 90th percentiles. Data were compared with a Mann-Whitney test. control RNAi vs wnt5 RNAi, **p=0.0025, n>41 animals; control vs slit RNAi, *p=0.0137, n>44 animals.

See also Figure S3.

If pole progenitors are specified at a pre-existing midline, what happens to planarian fragments lacking a midline? To address this question, we generated fragments that had little-to-no pre-existing midline with parasagittal amputation (Figure S3D). As expected, the anterior pole in the parasagittal thick fragments regenerated at the pre-existing midline (Figure S3E). The thin fragments, which had no pre-existing midline, displayed new slit expression, followed by an anterior pole (Figure S3F). This result is consistent with the possibility that anterior pole formation happens at the midline, and that body fragments lacking a midline undergo a process of de novo midline formation prior to anterior pole formation.

The Plane of Symmetry in Asymmetric Fragments is Centered on the Anterior Pole

The asymmetric formation of the anterior pole in amputated fragments lacking initial ML symmetry (Figure 3A) is consistent with the fact that obliquely amputated planarian body fragments produce head blastemas offset from the center of the wound face [1,27]. We assessed the expression patterns of multiple patterning genes (sFRP-1, ndl-2, wnt2, slit, and nlg7) in these regenerating, asymmetric fragments at seven days post amputation. The plane of spatial expression symmetry for each of these patterning molecules was centered at the regenerating anterior pole (Figure 3E, Figure S3C). The plane of symmetry during regeneration for many differentiated tissues, including the cephalic ganglia (PC2+), mechanosensory neurons (cintillo+), photoreceptor neurons (opsin+), GABAergic neurons (gad+), ciliated epidermis (rootletin+), secretory cells (mag-1+), and intestine (madt+), was also aligned with the location of the anterior pole (Figure 3E, Figure S3C). These results demonstrate for many tissues and gene expression domains that symmetry is centered around the pole, even if this position is offset from the ML midpoint of the wound face. These results are consistent with the role of the anterior pole in facilitating organization of new tissue pattern.

Midline Patterning Molecules Affect the Medial Zone of Pole Progenitor Specification

The appearance of pole progenitors at the prior (slit+) midline raised the possibility that the environment of the prior midline is permissive for pole progenitor specification at anterior-facing wounds. To test this possibility, animals were subjected to RNAi of wnt5 and slit, which regulate the planarian ML axis [26,28]. wnt5 negatively regulates the expression domain of slit. After 8 dsRNA feedings, wnt5(RNAi) animals displayed ectopic lateral eyes, and slit(RNAi) animals displayed ectopic medial eyes, confirming RNAi had perturbed medial-lateral pattern (Figure 3F). Furthermore, the slit expression domain was wider in wnt5(RNAi) animals and slit expression in slit(RNAi) animals was reduced and narrower than in controls (Figures S3G–H). Some wnt5(RNAi) animals had wider anterior poles than did control animals, whereas some of the slit(RNAi) animals had narrower poles than did control animals (Figures 3G–H). When we examined the distributions of pole-specialized neoblasts in these animals, we found that the distributions were wider in wnt5(RNAi) animals (Figures S3I–J). We conclude that the zone marked by expression of slit, and defined by antagonistic roles for wnt5 and slit, regulates the ML zone competent for pole progenitor specification at anterior-facing wounds.

Anterior Pole Progenitors Accumulate at the DV Median Plane of the Blastema

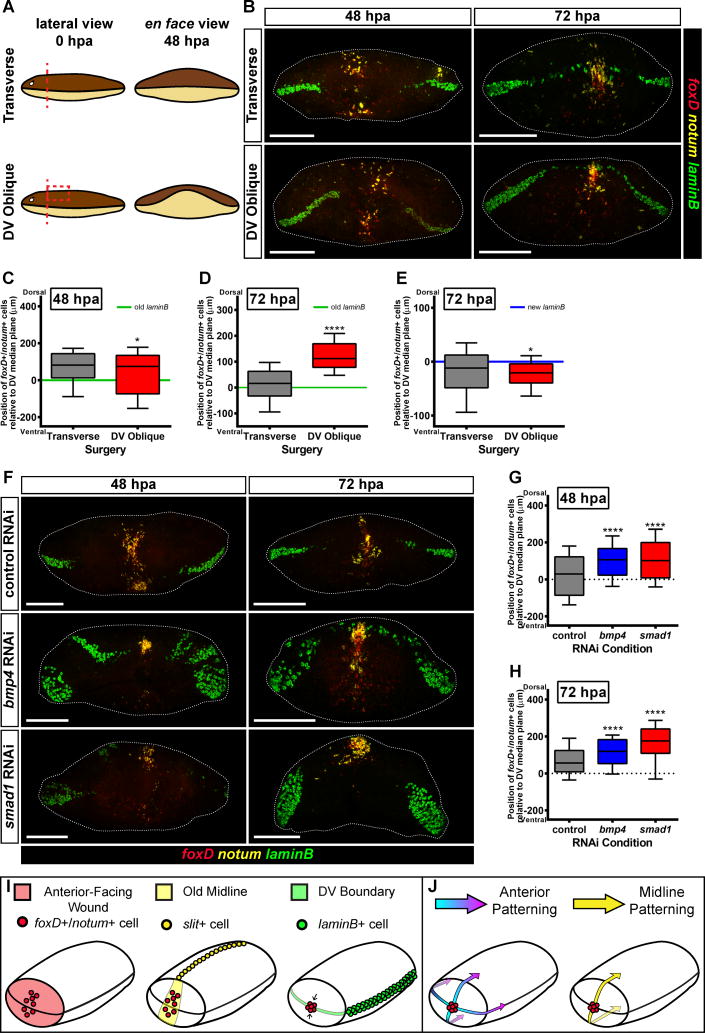

We next sought to understand how the anterior pole is placed at a particular location along the DV axis. Of the many surgeries applied to planarians, few create asymmetry along this shortest of planarian axes. We developed a DV oblique cut involving transverse amputation and dorsal tissue removal, creating a wound with more dorsal than ventral tissue removed (Figure 4A). Despite the severity of this wound, these animals eventually regenerated relatively normally (Figure S4A).

Figure 4. The final location of the anterior pole is influenced by the DV axis.

(A) Left panel: Cartoon of a transverse and DV oblique amputation. To generate DV oblique fragments, animals had a transverse amputation followed by a precise removal of dorsal tissue. Lateral view, dorsal is up. Right panel: In order to close the wound following a DV oblique cut, ventral tissue must migrate further to make contact with dorsal tissue and seal the wound. en face view, dorsal is up. (B) Wild-type animals were subjected to either a transverse or DV oblique amputation, fixed at 48 and 72 hpa, and expression of foxD (red), notum (yellow), and laminB (green) was analyzed by triple FISH. At 48 hpa, foxD+/notum+ cells appeared distributed along the DV axis, whereas at 72 hpa, cells accumulated near the new DV boundary, even when that domain was shifted dorsally to where it should be. (C) The distribution of foxD+/notum+ cells on the DV axis at 48 hpa was slightly wider in DV oblique animals, but not dorsally shifted. The transverse and DV oblique conditions were compared with a Mann-Whitney test. *p<0.0417, n>228 cells. (D) The distribution of foxD+/notum+ cells on the DV axis at 72 hpa was shifted dorsally in DV oblique animals. The transverse and DV oblique conditions were compared with a Mann-Whitney test. ****p<0.0001, n>297 cells. (E) The distribution of foxD+/notum+ cells on the DV axis was centered near the DV boundary in both transverse and DV oblique animals, and as a group cells were slightly closer to the DV boundary in DV oblique animals. The transverse and DV oblique conditions were compared with a Mann-Whitney test. *p<0.0152, n>230 cells. (F) control RNAi, bmp4(RNAi), or smad1(RNAi) animals were transversely amputated, fixed at 48 and 72 hpa, and expression of foxD (red), notum (yellow), and laminB (green) was analyzed by triple FISH. foxD+/notum+ cells were shifted dorsally in bmp4(RNAi) and smad1(RNAi) as compared to control RNAi animals. (G) The position of the anterior pole was shifted dorsally in bmp4(RNAi) and smad1(RNAi) animals at 48 hpa. Data were compared with a Mann-Whitney test. control RNAi vs bmp4 RNAi, ****p<0.0001, n>346 cells; control RNAi vs smad1 RNAi, ****p<0.0001, n>354 cells. (H) The position of the anterior pole is shifted dorsally in bmp4(RNAi) and smad1(RNAi) animals at 72 hpa. Data were compared with a Mann-Whitney test. control RNAi vs bmp4 RNAi, ****p<0.0001, n>295 cells; control RNAi vs smad1 RNAi, ****p<0.0001, n>295 cells. For (B) and (F) images shown are maximal intensity projections. Images are an en face view of the anterior blastema. Dorsal is up. Scale bars, 200 μm. For (C–D) and (G–H) the reference point for these coordinates is the DV median plane, which is estimated using old laminB expression (green or dotted line). For (E) the reference point for these coordinates is the DV boundary in the blastema, which was estimated using new laminB expression (blue line). The box is defined by the first quartile, median, and third quartile, and the whiskers are defined by the 10th and 90th percentiles. (I) Anterior pole formation relies on three landmarks at wounds in order to integrate the pattern of the new and pre-existing tissues: an anterior-facing wound, the prior midline, and the boundary between the dorsal and ventral sides of the animal. (J) Once the anterior pole is formed, it acts to help pattern the AP and ML axes of the regenerating head.

See also Figure S4.

DV oblique animals formed a line of laminB+ cells in the blastema that was shifted dorsally from the preexisting laminB+ plane, consistent with a dorsal shift in the boundary formed between the dorsal and ventral epidermis during wound closure (Figure 4A–B). Early after DV oblique injury, pole progenitors were distributed along the DV axis; at later timepoints the anterior pole coalesced far dorsal to the DV median plane of pre-existing tissue (Figure 4B–D). laminB expression in the blastema was used to estimate the DV boundary in the blastema at 72 hpa. Pole progenitors at 72 hpa were coincident with this new laminB expression plane (Figure 4E), suggesting that anterior pole progenitors accumulate near the approximate location of contact between the dorsal and ventral sides formed early during regeneration (DV boundary). At 7 days post injury, the expression gap in ndl-2, sFRP-1 expression, and the location of the brain as visualized by PC2 expression, were all shifted dorsally and retained their relative position to the anterior pole (Figure S4B).

Perturbation of Bmp Signaling Affects the DV Positioning of Pole Progenitors

To determine if the pre-existing DV axis has a role in positioning anterior pole progenitors, animals were subjected to RNAi of bmp4 and smad1, which normally promote dorsal tissue identity for the DV axis [29–31]. As previously reported, the laminB expression domain was thickened with ectopic dorsal patches in both bmp4 RNAi and smad1 RNAi animals (Figure 4F, Figure S4C) [29,32]. RNAi of bmp4 and smad1 causes ventralization; cells responding to Bmp activity levels for localization should be shifted dorsally when that signal is reduced. Indeed, anterior pole progenitors were shifted dorsally at 48 hpa relative to laminB+ cells in pre-existing tissue in both bmp4 and smad1 RNAi animals (Figure 4F). This result was confirmed by measuring the position of the anterior pole progenitors relative to the pre-existing DV median plane, and by examining their distributions (Figure 4G). This dorsal bias persisted at 72 hpa (Figure 4H). These results indicate that the correct DV localization of anterior pole progenitors requires Bmp signaling.

Conclusions

One of the central challenges of regeneration is having a system that is capable of responding to injuries with different wound site architectures to produce a correctly patterned animal. Regenerative tissue outgrowths (blastemas) likely initiate pattern formation by a mechanism distinct from what occurs at the beginning of embryogenesis given the drastically different starting conditions for these processes. Given prior RNAi data [2–4] and the head tip transplantation results, the anterior pole likely has an important role in determining how the planarian head blastema organizes its pattern. Our findings suggest that the position of anterior pole regeneration relies on three cues: an anterior-facing wound [2–4], the pre-existing midline, and the DV boundary in the blastema (Figure 4I). The positioning of the pole at the midline during regeneration can allow ML pattern of new tissue to align with ML pattern of pre-existing tissue. Coordinating AP axis information with a DV axial plane to set a point of tissue organization and growth has parallels to other biological systems, such as in Drosophila imaginal discs [33,34]. Positioning of an organizer at the DV median plane in regeneration could facilitate a vector of growth and pattern formation on the AP axis perpendicular to the old DV axis. Planarians use positional information actively as adults for maintenance and restoration of axial pattern [35]. We conclude that the process of anterior pole formation during regeneration integrates axial cues at wounds, providing a mechanism to coordinate patterning and growth during head regeneration in a manner coherent with pre-existing tissue pattern (Figure 4J).

Experimental Procedures

See the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. For information on genes used in this study please see Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Reddien Lab for comments and discussion. D.J.L is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (T32GM007753) and by the Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowship for New Americans. P.W.R. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an associate member of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. We acknowledge support from the NIH (R01GM080639).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, four figures, one table, and two movies, and can be found with this article online.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: IMO DJL MLS MAG PWR. Performed the experiments: IMO DJL MLS PWR. Analyzed the data: IMO PWR. Wrote the paper: IMO PWR. Revised the paper: IMO DJL MLS PWR.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Reddien PW, Sánchez Alvarado A. Fundamentals of Planarian Regeneration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:725–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scimone ML, Lapan SW, Reddien PW. A forkhead Transcription Factor Is Wound-Induced at the Planarian Midline and Required for Anterior Pole Regeneration. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1003999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vásquez-Doorman C, Petersen CP. zic-1 Expression in Planarian Neoblasts after Injury Controls Anterior Pole Regeneration. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogg MC, Owlarn S, Pérez Rico YA, Xie J, Suzuki Y, Gentile L, Wu W, Bartscherer K. Stem cell-dependent formation of a functional anterior regeneration pole in planarians requires Zic and Forkhead transcription factors. Dev Biol. 2014;390:136–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Driever W, Nüsslein-Volhard C. A Gradient of bicoid Protein in Drosophila Embryos. Cell. 1988;54:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Robertis EM, Larraín J, Oelgeschläger M, Wessely O. The establishment of Spemann’s organizer and patterning of the vertebrate embryo. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:171–81. doi: 10.1038/35042039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner DE, Wang IE, Reddien PW. Clonogenic Neoblasts Are Pluripotent Adult Stem Cells That Underlie Planarian Regeneration. Science. 2011;332:811–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1203983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersen CP, Reddien PW. Polarized notum activation at wounds inhibits Wnt function to promote planarian head regeneration. Science. 2011;332:852–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1202143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaviño MA, Wenemoser D, Wang IE, Reddien PW. Tissue absence initiates regeneration through Follistatin-mediated inhibition of Activin signaling. eLife. 2013;2:e00247. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts-Galbraith RH, Newmark PA. Follistatin antagonizes Activin signaling and acts with Notum to direct planarian head regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1363–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214053110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spemann H, Mangold H. Uber Induktion von Embryonalanlagen durch Implantation artfremder Organisatoren. Arch Fur Mikroskopische Anat Und Entwicklungsmechanik. 1924;100:599–638. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubois F. Contribution a l’etude de la migration des cellules de regeneration chez les Planaires dulcicoles. Bulletin Biologique de la France et de le Belgique. 1949 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugino H. Transplantation experiments in Planaria gonocephala. Jour Zool. 1937;7:373–439. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos FV. Studies on transplantation in planaria. Biol Bull. 1929;57:188–97. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos FV. Studies on transplantation in planaria. Physiol Zool. 1931;4:111–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandebois R. Intercalary regeneration and level interactions in the fresh-water planarian Dugesia lugubris. Roux’s Arch Biol. 1985;53:390–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00848890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato K, Orii H, Watanabe K, Agata K. The role of dorsoventral interaction in the onset of planarian regeneration. Development. 1999;126:1031–40. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scimone ML, Kravarik KM, Lapan SW, Reddien PW. Neoblast specialization in regeneration of the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:339–52. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill EM, Petersen CP. Wnt/Notum spatial feedback inhibition controls neoblast differentiation to regulate reversible growth of the planarian brain. Development. 2015;142:4217–29. doi: 10.1242/dev.123612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tazaki A, Kato K, Orii H, Agata K, Watanabe K. The body margin of the planarian Dugesia japonica: characterization by the expression of an intermediate filament gene. Dev Genes Evol. 2002;212:365–73. doi: 10.1007/s00427-002-0253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhoffer GT, Kang H, Sánchez Alvarado A. Molecular analysis of stem cells and their descendants during cell turnover and regeneration in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:327–39. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Wolfswinkel JC, Wagner DE, Reddien PW. Single-Cell Analysis Reveals Functionally Distinct Classes within the Planarian Stem Cell Compartment. Cell Stem Cell. 2014:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lapan SW, Reddien PW. dlx and sp6-9 Control Optic Cup Regeneration in a Prototypic Eye. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapan SW, Reddien PW. Transcriptome Analysis of the Planarian Eye Identifies ovo as a Specific Regulator of Eye Regeneration. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newmark PA, Sánchez Alvarado A. Bromodeoxyuridine specifically labels the regenerative stem cells of planarians. Dev Biol. 2000;220:142–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cebrià F, Guo T, Jopek J, Newmark PA. Regeneration and maintenance of the planarian midline is regulated by a slit orthologue. Dev Biol. 2007;307:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgan TH. Regeneration in Planarians. Arch Fur Entwickelungsmechanik Der Org. 1900;10:58–119. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurley KA, Elliott SA, Simakov O, Schmidt HA, Holstein TW, Sánchez Alvarado A. Expression of secreted Wnt pathway components reveals unexpected complexity of the planarian amputation response. Dev Biol. 2010;347:24–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Kicza AM, Sánchez Alvarado A. BMP signaling regulates the dorsal planarian midline and is needed for asymmetric regeneration. Development. 2007;134:4043–51. doi: 10.1242/dev.007138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molina MD, Saló E, Cebrià F. The BMP pathway is essential for re-specification and maintenance of the dorsoventral axis in regenerating and intact planarians. Dev Biol. 2007;311:79–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orii H, Watanabe K. Bone morphogenetic protein is required for dorso-ventral patterning in the planarian Dugesia japonica. Dev Growth Differ. 2007:345–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaviño MA, Reddien PW. A Bmp/Admp Regulatory Circuit Controls Maintenance and Regeneration of Dorsal-Ventral Polarity in Planarians. Curr Biol. 2011;21:294–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.FJDB, SMC, Diaz-Benjumea FJ, Cohen SM. Interaction between dorsal and ventral cells in the imaginal disc directs wing development in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;75:741–52. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90494-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diaz-Benjumea FJ, Cohen SM, FJ DB, SM C. Serrate signals through Notch to establish a Wingless-dependent organizer at the dorsal/ventral compartment boundary of the Drosophila wing. Development. 1995;121:4215–25. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddien PW. Constitutive gene expression and the specification of tissue identity in adult planarian biology. Trends Genet. 2011;27:277–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.