Abstract

Positron emission tomography (PET) is an immensely important imaging modality in biomedical research and drug development but must use selective radiotracers to achieve biochemical specificity. Such radiotracers are usually labeled with carbon-11 (t1/2 = 20 min) or fluorine-18 (t1/2 = 110 min), but these are only available from cyclotrons in a few simple chemical forms. [18F]Fluoroform has emerged for labeling tracers in trifluoromethyl groups but is severely limited in utility by low radioactivity per mass (low molar activity). Here we describe the synthesis of [11C]fluoroform, based on CoF3-mediated fluorination of cyclotron-produced [11C]methane. This process is efficient and repetitively reliable. [11C]Fluoroform shows versatility for labeling small molecules in very high molar activity (> 200 GBq/μmol), far exceeding that possible from [18F]fluoroform. Therefore, [11C]fluoroform represents a major breakthrough for labeling prospective PET tracers in trifluoromethyl groups at high molar activity.

Keywords: carbon-11, [11C]fluoroform, PET, radiochemistry, trifluoromethyl

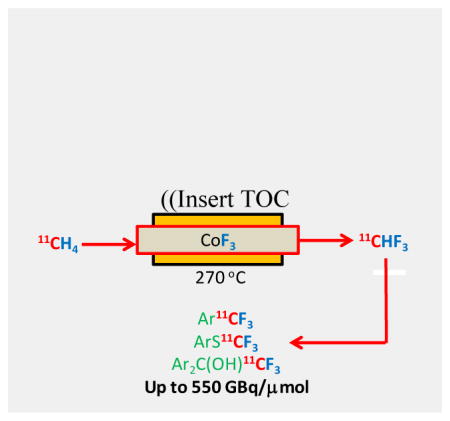

Graphical Abstract

Co(III) fluoride mediates efficient transformation of cyclotron-produced [11C]methane into [11C]fluoroform with high molar activity. [11C]Fluoroform shows broad utility as an efficient labeling synthon for prospective PET radiotracers.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is immensely important for biomedical research and for drug discovery and development. The value of PET for imaging molecular targets in a living human or animal subject depends on biochemically specific radiotracers being available, where the radiolabel is usually one of the short-lived cyclotron-produced positron-emitters, carbon-11 (t1/2 = 20.4 min) or fluorine-18 (t1/2 = 109.8 min). The label position is often critical for avoiding troublesome radiometabolites that may confound attempts to quantify radiotracer interaction with the imaging target.1 Therefore, in many cases it is preferable to label in one part of the structure rather than in another. A further very important consideration is the molar activity of the radiotracer, namely the radioactivity (Bq) per total mass of tracer (mol), where the latter is predominantly the accompanying non-radioactive tracer known as carrier. For low density imaging targets, such as enzymes, transporters, receptors and plaques, the radiotracer molar activity needs to be very high. A low molar activity may result in far too high occupancy of the target by carrier with consequent violation of the tracer principle, or even to obliteration of any target-specific signal.1 Minimal occupancy of the target by carrier may also be needed to avoid unwanted pharmacological effects. 2

The most popular methods for labeling PET radiotracers at high molar activity use [11C]methyl iodide or [18F]fluoride ion as labeling agents.1b [11C]Methyl iodide is produced from cyclotron-produced [11C]methane or [11C]carbon dioxide, whereas [18F]fluoride ion is produced directly from a cyclotron.1b However, the use of these labeling agents or of others restricts the kind of groups that might be labeled in radiotracers, for example to methyl (Me) groups for [11C]methyl iodide1b,3 and to monofluoro (CF) groups for [18F]fluoride ion.1b,4

Many drugs and potential PET radiotracers contain trifluoromethyl (CF3) groups. A methyl, chloro or other substituent can often be replaced with a CF3 group with good retention of physicochemical and pharmacological properties.5 Also, the CF3 group is generally considered to be metabolically stable. Consequently, Pharma develops many drugs with CF3 groups. In parallel, academic groups are developing methods for labeling such groups with fluorine-18,6 with the most recent methods being based on conversion of [18F]fluoride ion into [18F]fluoroform7, and then in-situ generation of the reactive derivative [18F]CuCF38 (Figure 1). These [18F]fluoroform production methods at best deliver only moderate molar activity (<32 GBqμmol−1) due to [18F]fluoride ion dilution with carrier fluoride ion in the solution reaction systems. Generally, the radiotracer molar activities that are needed for PET imaging of low density protein targets are several-fold higher.1b,9 The range of useful PET radiotracers that may be produced from [18F]fluoroform or [18F]CuCF3 that is produced by the best-performing methods is therefore limited to the low proportion not requiring such high molar activities.

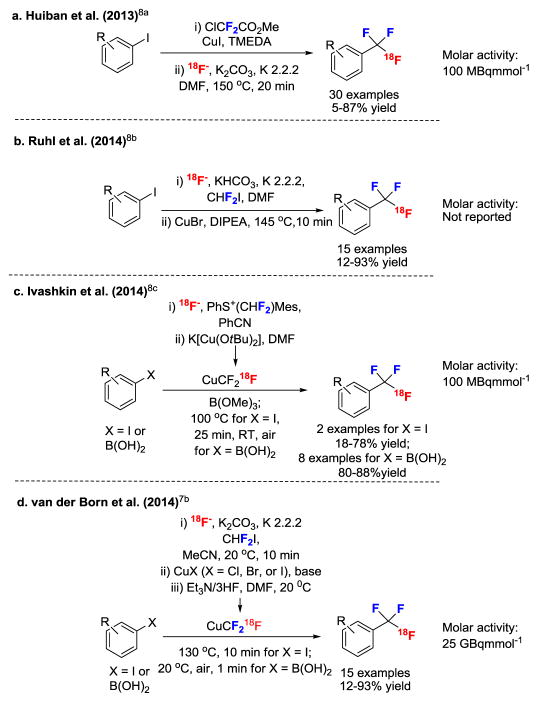

Figure 1.

Methods for the synthesis of [18F]fluoroform or the derivative [18F]CuCF3 for conversion into [18F]trifluoromethylarenes.

We noted that 11C-labeling of the trifluoromethyl group has never been achieved at any molar activity. [11C]Methane is produced in high activity in numerous PET research facilities, either directly by the 14N(p,α)11C nuclear reaction on nitrogen-10% hydrogen or by reduction of cyclotron-produced [11C]carbon dioxide. By either route, [11C]methane typically has very high molar activity that well exceeds that of cyclotron sources of fluorine-18.10,11 We reasoned that if [11C]fluoroform could be produced from readily accessible [11C]methane, very high molar activity might be retained and well exceed that currently achievable for [18F]fluoroform or [18F]CuCF3. Moreover, [11C]fluoroform would be expected to participate in labeling reactions without any further dilution with carrier, and therefore the labeling of PET radiotracers in trifluoromethyl groups at high molar activity would then become possible. Therefore we aimed to produce [11C]fluoroform form [11C]methane.

To meet our objective, a rapid and efficient fluorination method was required. In order to maintain high molar activity in the [11C]fluoroform, the method would need to be applicable to [11C]methane in the presence of only a low amount of carrier methane (typically ≪1 μmol) and without introducing an appreciable amount of extra carrier. Moreover, the method would need to be amenable to easy remote-control within a lead-shielded ‘hot-cell’ for radiation safety to personnel.

We noted that heated cobalt(III) fluoride (CoF3) has been used to fluorinate hydrocarbons to give mixtures of fluorinated products on a macro-scale.12 An unappealing feature of a typical fluorination process was that the CoF3 needed to be generated in situ by passing fluorine gas over heated CoF2. Nonetheless, we noted that CoF3 is now commercially available and might be used to avoid any need for noxious and highly reactive fluorine. Passage of [11C]methane over heated CoF3 therefore seemed an attractive possibility for producing [11C]fluoroform, provided that over-fluorination of the sub-micromole amount of carrier methane would not be a major issue nor the formation of other hydrocarbon byproducts. Therefore, we set out to test the feasibility of using commercially available CoF3 for producing [11C]fluoroform in useful yield.

Herein, we report that heated CoF3 successfully mediates efficient conversion of [11C]methane into [11C]fluoroform. We further report a remotely controllable and reliable apparatus for [11C]fluoroform production, and illustrate the utility of the [11C]fluoroform for labeling model compounds and examples of drug-like compounds by various chemical routes, some known and some novel. These labeled compounds show very high molar activities that match those to be expected6 from cyclotron-produced [11C]methane in the absence of further dilution with carrier and which far exceed those previously attained for [18F]fluoroform or [18F]CuCF3. In particular, these molar activities rival those for PET radiotracers commonly used for imaging low density protein targets, such as neurotransmitter receptors, transporters, enzymes and plaques.

Our initial experiments showed that [11C]methane readily passed through a heated column of commercial CoF3 without any hold-up of radioactivity or any restriction of flow and with some production of [11C]fluoroform. Figure 2 illustrates the apparatus that we finally developed for routinely preparing [11C]fluoroform after further experimentation.

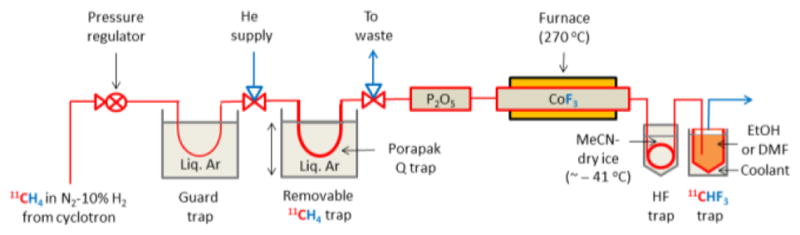

Figure 2.

Apparatus for producing [11C]fluoroform. Cyclotron-produced 11CH4 in N2-10% H2 is passed first through a cold (–186 °C) stainless steel U-tube and then another cold U-tube (–186 °C) containing Porapak Q. Waste gas goes to a collection bag. The U-tube is then raised and allowed to warm to RT over 4 min while the tube is also flushed with He gas (20 mLmin−1) to transfer the 11CH4 over Sicapent and into a heated (270 °C) stainless steel tube containing CoF3 (17 g). The effluent passes through MeCN-dry-ice (~ −41 °C) to trap any trace HF (b.p. 19.5 °C) and then into a trap containing EtOH cooled with hexane-liquid N2 (~−94 °C) or DMF cooled with MeCN-dry ice (~−41 °C) to trap the generated [11C]CHF3. See Supporting Information for complete apparatus construction and operation details.

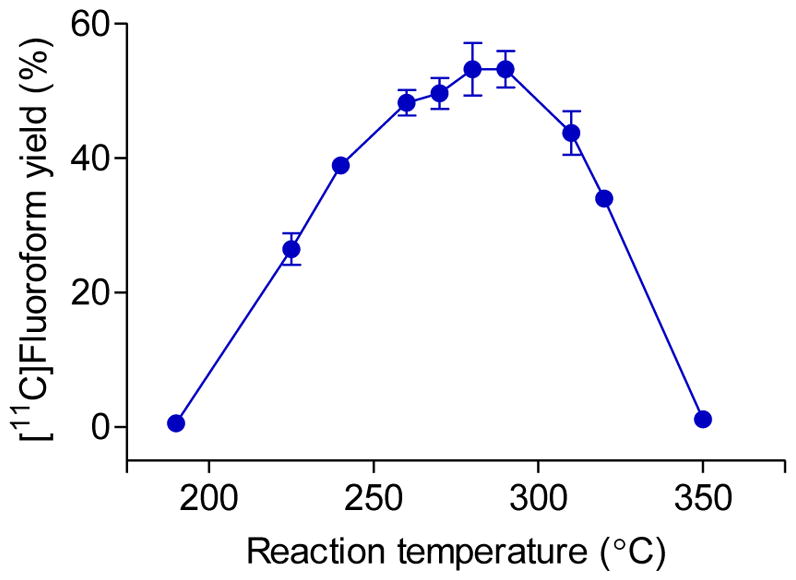

The temperature dependence of the conversion of [11C]methane into [11C]fluoroform was investigated in the apparatus with carrier helium flow set at 20 mLmin−1. Radioactivity trapped in cold (~ −94 °C) ethanol was used to calculate the yield (radioactivity breakthrough was relatively low). High yields of [11C]fluoroform were obtained between 260 and 290 °C (Figure 3). The average yield of [11C]fluoroform in this range was 53±4%, based on 11 experiments conducted with two different CoF3 columns. The overall process for producing [11C]fluoroform from [11C]methane required only 7 min from the end of a cyclotron irradiation, and was thus much less than one half-life of carbon-11.

Figure 3.

Dependence of yield of [11C]fluoroform from [11C]methane on temperature. Values are means ± S.D (n >3).

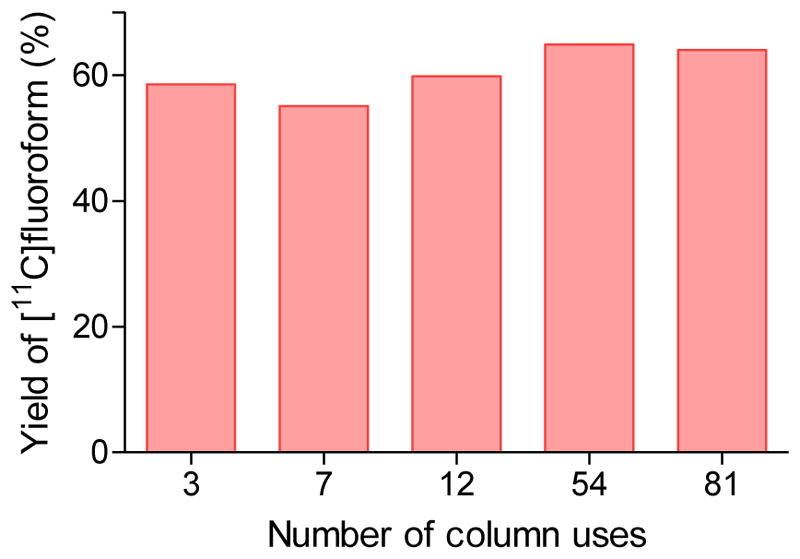

Whereas we observed that heating a CoF3 column to 350 °C many times resulted in severely impaired performance, initial conditioning of a newly installed CoF3 column by heating it once to 350 °C while sealed under helium subsequently resulted in optimal yields of [11C]fluoroform at lower temperatures. Moreover, such a heat-conditioned CoF3 column showed remarkably consistent performance over a very large number (> 80) of [11C]fluoroform productions (Figure 4). Therefore, once set up and conditioned, the apparatus required no significant maintenance other than to be kept filled with helium. Also the apparatus was very simply adapted for automation and remotely control to ensure radiation protection to personnel (see Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Dependence of [11C]fluoroform yields on the number of CoF3 column uses. Data are for the column operating at 270 °C with helium flow set at 20 mLmin−1.

The robustly repeatable performance of a conditioned CoF3 column suggests that the fluorination process does not depend on prior decomposition of CoF3 to CoF2 and fluorine. More likely is that the [11C]methane interacts directly and stoichiometrically with CoF3 to replace one hydrogen atom with fluorine to give [11C]fluoromethane, with this replacement process repeated until [11C]fluoroform is formed.

The reactivity of [11C]fluoroform was tested on model substrates (Figure 5). When [11C]fluoroform in DMF was added to a solution of benzophenone (1) and t-BuOK at RT, [11C]α-(trifluoromethyl)-benzhydrol ([11C]2) was obtained quantitatively in just 5 min. Treatment of 4-nitrophenylboronic acid (3) with [11C]fluoroform under Cu(I)-mediated conditions7b,8c for 1 min at RT gave [11C]1-nitro-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzene ([11C]4) in 99% yield with a molar activity of 551 GBqμmol−1. This molar activity is over 20-fold higher than that reported for [18F]4 prepared from [18F]fluoroform. Similarly, Cu(I)-mediated treatment of 3-fluorophenylboronic acid (5) with [11C]fluoroform gave [11C]1-fluoro-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzene; [11C]6) in 98% yield and with a molar activity of 242 GBqμmol−1. Together, these results confirmed that [11C]fluoroform was produced from [11C]methane without appreciable dilution of molar activity.

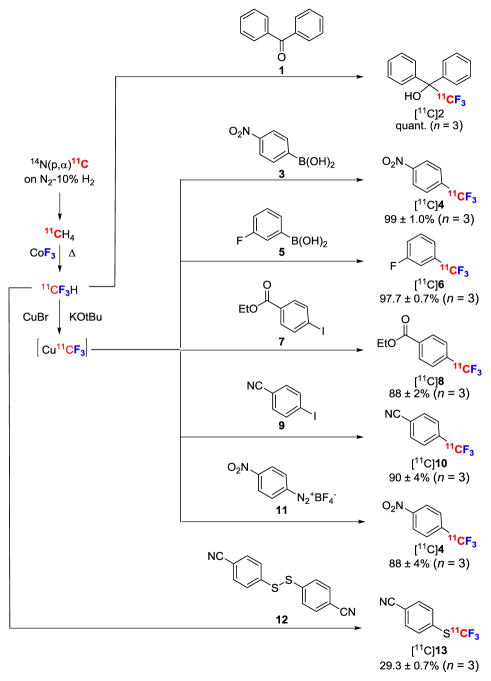

Figure 5.

Preparation and use of [11C]fluoroform for labeling model organic compounds with trifluoromethyl groups.

We also investigated the reactivity of [11C]fluoroform towards other substrates. Thus, under Cu(I)-mediated conditions,5b ethyl 4-iodobenzoate (7) and 4-iodobenzonitrile (9) were converted rapidly into ethyl [11C]4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoate ([11C]8) and [11C]4-(trifluoromethyl)benzonitrile ([11C]10) in 88 and 90% yields, respectively. These high yields attest to the absence of troublesome impurities in the collected [11C]fluoroform; only low levels of minor unreactive fluorinated-11C species were ever seen as contaminants.

The easy access to [11C]fluoroform enabled us to explore the development of new labeling chemistries. Thus, we showed that treatment of a commercially available ‘wet’ diazonium salt 11 with [11C]CuCF3 gave [11C]4 in high yield approaching that from the boronic acid precursor 3. Moreover showed the versatility of [11C]fluoroform for labeling diverse functional groups through its reaction with the diaryldisulfane 12, which gave the labeled trifluoromethylsulfur arene [11C]13 rapidly (<10 min) in 29% non-optimized yield.

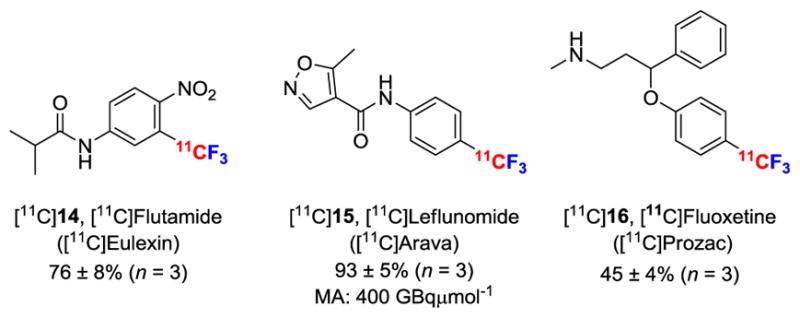

Finally, we demonstrated the utility of [11C]fluoroform for labeling trifluoromethyl groups with carbon-11 in drug-like or PET radiotracer-type molecules. For example, we used [11C]fluoroform to label three known drugs, namely the antiandrogen flutamide (Eulexin) (14), the antirheumatic drug leflunomide (Arava) (15), and the antidepressant fluoxetine (Prozac) (16) (Figure 6). [11C]14 was obtained in 76% yield from the corresponding iodo-precursor (17) and [11C]fluoroform under Cu(I)-mediated conditions. This yield compares very favorably with that of [18F]14 prepared with the much lower molar activity method of Huiban et al.8a (55%). [11C]15 was labeled in 93% yield and with a high molar activity of 400 GBqμmol−1 (corrected to end of radionuclide production) from the Cu(I)-mediated reaction on the corresponding boronic acid precursor (19). Finally, [11C]16 was obtained in 45% yield from a Cu(I)-mediated reaction on a Boc-protected iodo precursor (20) followed by deprotection.

Figure 6.

11C-Labeled drugs prepared from NCA [11C]fluoroform.

In conclusion, [11C]fluoroform is readily and simply produced in usefully high yield and in high molar activity from cyclotron-produced [11C]methane by passage over heated CoF3. The process is rapid, repetitively robust and low-maintenance. [11C]Fluoroform represents a breakthrough as an agent for labeling PET radiotracers at trifluoromethyl groups in high molar activity sufficient for imaging low density targets in human subjects. We now envisage access to an enhanced range of exciting radiotracers for PET applications based on adapting the known richly diverse chemistry of fluoroform13 to [11C]fluoroform for unprecedented 11C-labeling at trifluoromethyl groups.

Experimental Section

Production of [11C]fluoroform

The apparatus (Figure 2) was constructed, set-up and operated as detailed in Supporting Information. The collected [11C]fluoroform was analyzed with HPLC (see Supporting Information).

Conversion of [11C]fluoroform into [11C]CuCF3

Within a glovebox, t-BuOK in DMF (0.3 M, 50 μL, 15 μmol) was added to CuBr (0.7 mg, 5 μmol) in a 1-mL vial. The vial was septum-sealed and removed from the glovebox. [11C]Fluoroform (185–555 MBq) in DMF (50–300 μL) was added to the vial, mixed and left at RT for 1 min. A solution of Et3N.3HF in DMF (1.64% v/v; 5 μL) was then added. The mixture was mixed thoroughly and allowed to stay at RT for another minute.

Labeling reactions

For details of labeling reactions and product analyses see Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIMH; ZIA MH002793). We are grateful to Mr. George Dold and colleagues (NIMH) for apparatus construction and the NIH Clinical Center (Chief: Dr. P. Herscovitch) for cyclotron production of carbon-11.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

This work is the subject of a patent application.

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document

References

- 1.a) Pike VW. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:431. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pike VW. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23:1818. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160418114826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Lapi SE, Welch MJ. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:601. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hume SP, Gunn RN, Jones T. Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25:173. doi: 10.1007/s002590050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jagoda EM, Vaquero JJ, Seidel J, Green MV, Eckelman WC. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:771. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wuest F, Berndt M, Kniess T. In: PET chemistry, The Driving Force in Molecular Imaging. Schubiger PA, Lehmann L, Friebe M, editors. X. Springer-Verlag GmbH; New York: 2007. p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai L, Lu S, Pike VW. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:2853. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Zhu W, Wang J, Wang S, Gu Z, Aceña JL, Izawa K, Liu H, Soloshonok VA. J Fluor Chem. 2014;167:37. [Google Scholar]; b) Bassetto M, Ferla S, Pertusati F. Future Med Chem. 2015;7:527. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lien VT, Riss PJ. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:10. doi: 10.1155/2014/380124. Article ID 380124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/380124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) van der Born D, Herscheid JDM, Orru RVA, Vugts DJ. Chem Commun. 2013;49:4018. doi: 10.1039/c3cc37833k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) van der Born D, Sewing C, Herscheid JDM, Orru RVA, Windhorst AD, Vugts DJ. Angew Chem Ind Ed. 2014;53:11046. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Huiban M, Tredwell M, Mizuta S, Wan Z, Zhang X, Collier TL, Gouverneur V, Passchier J. Nature Chem. 2013;5:941. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rühl T, Rafique W, Lien VT, Riss P. Chem Commun. 2014;50:6056. doi: 10.1039/c4cc01641f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ivashkin P, Lemonnier G, Cousin J, Grégoire V, Labar D, Jubault P, Pannecoucke X. Chem, Eur J. 2014;20:9514. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madsen K, Marner L, Haahr M, Gillings N, Knudsen GM. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:1085. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christman DR, Finn RD, Karlstrom KI, Wolf AP. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1975;26:435. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Buckley K, Huser J, Jivan S, Chun K, Ruth T. Radiochim Acta. 2000;88:201. [Google Scholar]; b) Andersson J, Truong P, Halldin C. Appl Radiat Isot. 2009;67:106. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Björk H, Dahlström K, Bergström J-O, Truong P, Halldin C. 10th Workshop on Targetry and Target Chemistry; Madison, Wisconsin. p. 12. Abstract no. A02. [Google Scholar]; d) Gómez-Vallejo V, Gaja V, Koziorowski J, Llop J. In: Positron Emission Tomography — Current Clinical and Research Aspects. Schubiger PA, Lehmann L, Friebe M, Hsieh C-H, editors. X. Ch 7. Rijeka: InTech; 2012. p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Asovich VS, Kornilov VV, Kostyaev R, Maksimov VN. Russ J Appl Chem. 1994;67:94. [Google Scholar]; b) Kornilov VV, Kostyaev RA, Maksimov BN, Mel’nichenko BA, Fedorova T. Russ J Appl Chem. 1995;68:1227. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Lishchynskyi A, Guillaume B, Grushin VV. Chem Comm. 2014;50:10237. doi: 10.1039/c4cc04930f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Russell J, Roques N. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:13771. [Google Scholar]; c) Folléas B, Marek I, Normant JF, Saint-Jalmes L. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:275. [Google Scholar]; d) Surya PGK, Jog PV, Batamack PTD, Olah GA. Science. 2012;338:1324. doi: 10.1126/science.1227859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Kawai H, Yuan Z, Tokunaga E, Shibata N. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:1446. doi: 10.1039/c3ob27368g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.