Abstract

The posttranscriptional mechanisms whereby RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) regulate T cell differentiation remain unclear. RBPs can coordinately regulate the expression of functionally related genes via binding to shared regulatory sequences, such as the Adenylate-Uridylate-Rich Elements (ARE) present in mRNA’s 3′ untranslated region (UTR). The RBP HuR posttranscriptionally regulates IL-4, IL-13 and other Th2-cell-restricted transcripts. We hypothesized that the ARE-bearing GATA-3 gene, a critical regulator of Th2 polarization, is under HuR control as part of its coordinate posttranscriptional regulation of the Th2 program. We report that in parallel with stimulus-induced increase in GATA-3 mRNA and protein levels, GATA-3 mRNA half-life is increased after restimulation in the human T cell line Jurkat, in human memory and Th2 cells and in murine Th2-skewed cells. We demonstrate by immunoprecipitation of ribonucleoprotein complexes that HuR associates with the GATA-3 endogenous transcript in human T cells and found, using biotin pull-down assay, that HuR specifically interacts with its 3′UTR. Using both loss- and gain-of-function approaches in vitro and in animal models, we show that HuR is a critical mediator of stimulus-induced increase in GATA-3 mRNA and protein expression and that it positively influences GATA-3 mRNA turnover, in parallel with selective promotion of Th2 cytokine overexpression. These results suggest that HuR-driven posttranscriptional control plays a significant role in T cell development and effector function in both murine and human systems. A better understanding of HuR-mediated control of Th2 polarization may have utility in altering allergic airway inflammation in human asthmatic patients.

Keywords: Inflammation, Posttranscriptional gene regulation, RNA-binding proteins, HuR, GATA-3, Th2 cytokines, T cells

Introduction

The process of T cell activation involves complex phenotypic and functional changes that are dynamically modulated throughout the different stages of an immune response. Coordinate action of multiple gene regulatory pathways insures that the different molecular species involved in the T cell response are expressed with the proper timing, magnitude and duration. To this end, chromatin remodeling and transcriptional activation are highly integrated with posttranscriptional mechanisms, which specifically regulate the rate of mRNA transport, turnover and translation. It has been established that the activation of human T cells determines global, coordinate changes of mRNA turnover rates that impact more than half of the induced gene pool (1–3), and research in the last decade has identified several cis-elements and trans-factors that mediate these processes in T cells (4).

Messenger RNA molecules exist within the cell as components of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, in association with a host of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that dynamically interact with the mRNAs and modulate their correct splicing, nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, turnover and translation rates (5). Several conserved regions have been identified and recently defined as USER (Untranslated Sequence Elements for Regulations), as they are preferentially located in the mRNA untranslated regions (UTR), particularly in the 3′UTR (4, 6, 7). Among these, the Adenylate-uridylate-Rich Elements (ARE) are the most conserved and well-characterized regulatory elements mediating changes in mRNA turnover and translation in immune genes (8). ARE-mediated gene regulation occurs for many T cell cytokine genes such as IL2, IL3, CSF2, IL4, and IL13, although alternative USER do play a role in T cell gene regulation (4). Multiple ARE-binding proteins, acting either in a cooperative or exclusive fashion, regulate mRNA stability and translation and adapt the amplitude and duration of gene expression according to the cellular environment (5).

Genome-wide studies examining the transcript pools selectively associated with distinct RBPs have established that functionally related mRNAs that share a USER, such as the ARE, can be coordinately regulated by one or more cognate RBPs (6, 9). The ubiquitous RBP HuR binds to a heterogeneous group of AREs and is functionally characterized as a positive regulator of mRNA stability and/or translation, acting through multiple, often independent mechanisms yet to be fully characterized (10). HuR has been characterized as a critical positive regulator of genes transcribed in effector T cell polarized subsets and in the generation of T cells in the thymus (11–13). T cell activation induces HuR nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (12, 14–17), an event reflecting its functional activation, and positively regulates the mRNA turnover of several T cell-derived genes (15, 18–24). The complex role of HuR in T cell biology is also revealed by recent conditional knock-out mouse models. When the HuR gene was ablated in T cells using an lck cre recombinase system, the mouse phenotype was characterized by numerous abnormalities of T cell ontogeny (13). Another model of tamoxifen-inducible HuR conditional knock-out displayed atrophy of multiple organ systems due to apoptosis of progenitor cells in thymus, bone marrow and intestine (25).

The role of of HuR in Th2-restricted gene expression is supported by its established role in promoting IL-4 and IL-13 mRNA stability (14, 26, 27). We also showed that another selective marker of Th2 cells, the chemotactic PGD2 receptor CRTH2, is also regulated at the level of mRNA turnover (28). Interestingly, CRTH2 transcript, i.e., the product of the GPR44 gene, also harbors HuR binding sites (29). On this basis, we could infer that HuR may represent the posttranscriptional counterpart for nuclear proteins directing lineage-restricted transcription of these genes. One such protein is GATA-3, a factor that controls the coordinate expression of Th2 genes at both the epigenetic and transcriptional level (30, 31). GATA-3 is itself a Th2-selective marker, and its lineage-restricted induction is thought to be mediated by both intrinsic and extrinsic, instructive pathways (32, 33). While IL-4 has been primarily involved in GATA3 transcriptional activation via the JAK3-STAT6 pathway (32, 34), little is known about the contribution of posttranscriptional pathways to GATA3 expression. We and others have shown previously that, in airway epithelial cells, IL-4 can contribute to STAT6-dependent transcriptional signals and STAT6-independent posttranscriptional signals, the latter through the activation of HuR, in the regulation of CCL11 (24, 35, 36). It can be hypothesized then that GATA3, being an ARE-bearing gene activated by IL-4, might be regulated in a similar fashion. The regulation of a critical transcriptional effector of the Th2 gene program such as GATA-3 would provide an additional level at which HuR participates in the regulation of the coordinate expression of Th2-restricted genes, and lineage-restricted genes more in general. In light of these considerations, we investigated whether the GATA3 gene is part of a transcript pool under coordinate posttranscriptional control exerted by HuR, and evaluated the functional outcome of HuR regulation. Our results implicate HuR as a novel determinant of GATA-3 mRNA and protein levels in human and mouse T cells, involved in the control of GATA-3 mRNA stability as one of potentially multiple means of HuR-driven posttranscriptional regulation in T cells.

Methods

Cell Culture

Blood was obtained from healthy subjects under a protocol approved by a Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB and from buffy coats (Biological Specialty Corporation, Colmar, PA). Th2-skewed cells were generated in vitro as described (27, 37) and intracellular staining for IL-13, IL-4 and IFN-γ to quantify cell polarization was performed as established (27, 37). Human memory T cells were isolated using Memory CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and following manufacturer’s protocol. The human Jurkat T cell line was cultured in RPMI, 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen) and 100 μg/ml gentamycin (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD). The H2 cells, a clone of the human cell line H1299, a non-small cell lung carcinoma stably transfected with the pTet-Off plasmid (Clontech) (38), were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen), 10% FBS and penicillin (100 U/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (27). NIH/3T3 cells were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) and 10% BCS.

Murine T cell polarization in vitro

Naïve splenocytes were isolated from 8-wk-old female FVB HuR transgenic mice and female wild-type FVB mice. CD4+ T cells were isolated using CD4 (L3T4) MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were activated with anti-CD3 anti-CD28 (5 μg/ml each ) for 5 days in 10% FCS-DMEM media under Th1 polarizing (20 ng/ml rIL-12 and 20 μg/ml anti-IL-4 antibody), Th2 polarizing (20 ng/ml rIL-4 and 20 μg/ml anti-IFN-γ antibody), or non-polarizing conditions (no cytokines and blocking antibodies).

HuR silencing

Jurkat T cells were stably transfected using a lentivirus expressing a HuR shRNA as described (39). Alternatively, Jurkat T cells were transiently transfected with using previously described HuR siRNA (5′-AAGAGUGAAGGAGUUGAAACU-3′) or a scrambled control (5′-GCCAAUUCAUCAGCAAUGG, Qiagen (27). The same reagents were used to transfect primary human T cells using Amaxa Human T cell Nucleofector Kit and Nucleofector Device (Lonza) following manufacturer’s protocol.

Plasmid constructs and transfection protocols

The pTetBBB-GATA-3′UTR construct was generated by amplification from a Jurkat genomic template (Accession Number: NM_002051) and subsequently cloned into the unique BglII site of pTetBBB (40). Primers to amplify the GATA-3 3′UTR (forward/reverse) are described in Supplemental Table 1.

Transient transfection of H2 cells was done as described (27). Expression of eGFP or β-globin was allowed for 48h, transcription was then stopped by addition of doxycycline (DOX, 1 μg/ml), and mRNA decay was measured by Northern blot from total RNA harvested at different times from the addition of DOX (27).

RNA Isolation and Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) (41). Cytoplasmic RNA was isolated and DNase-treated with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA was reverse-transcribed using the Gene Amp Kit (Perkin-Elmer) and PCR amplified using the SYBR Green reagent Kit (Perkin Elmer). Northern blot analysis was carried out as described (24). The probe was a cDNA encompassing the full-length coding region of rabbit β-globin (40). The PCR primers (forward/reverse) for real-time PCR analysis are listed in Supplemental Table 1 and amplification parameters were applied as described (27) All samples were run in triplicate (SD < 0.1) for real-time fluorimetric determination in an ABI 7300 sequence detector (Perkin Elmer) and quantified using the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method (24, 42) using GAPDH mRNA expression for normalization.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting analysis was performed as described (27, 39) using anti-HuR clone 3A2 (1 μg/ml) (43) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-HA clone D66 (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-GATA-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-β-tubulin (1 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich). HuR and GATA-3 densitometric levels were determined using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad) after normalization to β-tubulin.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) of endogenous messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes (mRNP)

We used a modification of an established protocol (24, 27, 44). Jurkat cell lysates were obtained using polysome lysis buffer (PLB). For IP, Protein A-Sepharose beads (Sigma) were swollen 1:1 v/v in NT2 buffer. A 100-μl aliquot of the preswollen protein A bead slurry was used for IP reaction and incubated 4 h at RT with excess immunoprecipitating antibody, using the 3A2 anti-HuR antibody or an IgG1 isotype control antibody (B&D Life Sciences). The antibody-coated beads were washed with ice-cold NT2 buffer and resuspended in 900 μl of NT2 buffer supplemented with 100 U/ml RNaseOUT, 0.2% vanadyl-ribonucleoside complex, 1 mM DTT, and 20 mM EDTA. The IP reactions were tumbled at RT for 2 h, and washed beads were resuspended in 100 μl NT2 buffer supplemented with 0.1% SDS and 30 μg proteinase K, and incubated for 30 min at 55°C. The cytoplasmic RNA was extracted using phenol-chlorophorm-isoamylalcohol and precipitated in ethanol.

In vitro biotin pull-down assay

Biotinylated transcripts were generated by RT-PCR of Jurkat RNA for human transcripts or cDNA from pYX-Asc GATA-3 CDS BC062915 (Open Biosystems) for murine transcripts using forward primers that contained a T7 transcription initiation site [GTGAATTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG] as described (27). The primers used to generate cDNA are listed in Supplemental Table 1. PCR products were purified from agarose gels as described (45), and used as templates for the synthesis of biotinylated RNAs using T7 RNA polymerase and biotin-conjugated CTP for human RNAs or UTP for murine RNAs. Following an established protocol (29), cytoplasmic fractions of unstimulated Jurkat cells (40 μg) or NIH/3T3 cells (40 μg) were incubated for 1 h at RT with 1 μg of biotinylated transcripts, then RNP complexes were isolated with streptavidin-conjugated Dynabeads (Invitrogen). The presence of HuR in the pull-down pellet was verified by Western blot analysis (27). For generation of mutant biotinylated transcripts, AU-rich elements in the GATA-3′ UTR from the pYX-Asc GATA-3 CDS plasmid were mutated from [AATTGTTGTTTGTATG] to [TTTATTATGTTAGGTTG] at 2270–2286 and from [TGGAATAATACTATAA] to [ATAATAGATGATAACT] at 2762–2778 by site-directed mutagenesis (Mutagenex, Hillsborough, New Jersey).

Generation of the HuR transgenic mouse

A hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged HuR fragment containing SalI sites on both the 5′ and 3′ end was cloned in the SalI site of the mCD4.e/p-SalI(−) plasmid (46), which replaced the CD2 gene with HA-HuR. Plasmids were digested with NotI to remove bacterial genes. Fragments were then microinjected into FVB pronuclei and transplanted into an FVB female. Founder mice and their progeny were screened for the presence of the transgene using primers specific for HA-HuR. No gross abnormalities in organ architecture were found as determined by the University of Missouri Veterinary School Research Animal Diagnostic Laboratory (RADIL).

Intracellular staining and flow cytometry

In vitro polarized T cells were restimulated with 50 ng/ml PMA, 500 ng/ml ionomycin and 1 μg/ml brefeldin A for 6 h. Cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% saponin, then stained with anti-IL-4 FITC and anti-IFN APC (BD Bioscience). For GATA-3 intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Foxp3 Fix/Perm buffer set (BD Bioscience) and then stained with anti-GATA-3 (eBioscience). Cells were analyzed on the CyAn flow cytometer (Becton Coulter) using FloJo software. For detection of HA and HuR by intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Fix/Perm buffer set (BD Bioscience), stained with either 2 μg anti-HA (Sigma-Aldrich) or 2 μg anti-HuR (3A2) and then incubated with PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG to detect either HA or HuR. Cells were analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) using Cellquest software (BD Bioscience).

Cytokine assays

Supernatants (diluted 1:200) were used for cytokine detection using mIL-4, IL-13 or IFNγ ELISA Ready-SET-Go kit (eBioscience).

Statistical Analysis

The p values were calculated using the two-tailed Student t test.

Results

Activation-induced stabilization of GATA-3 mRNA

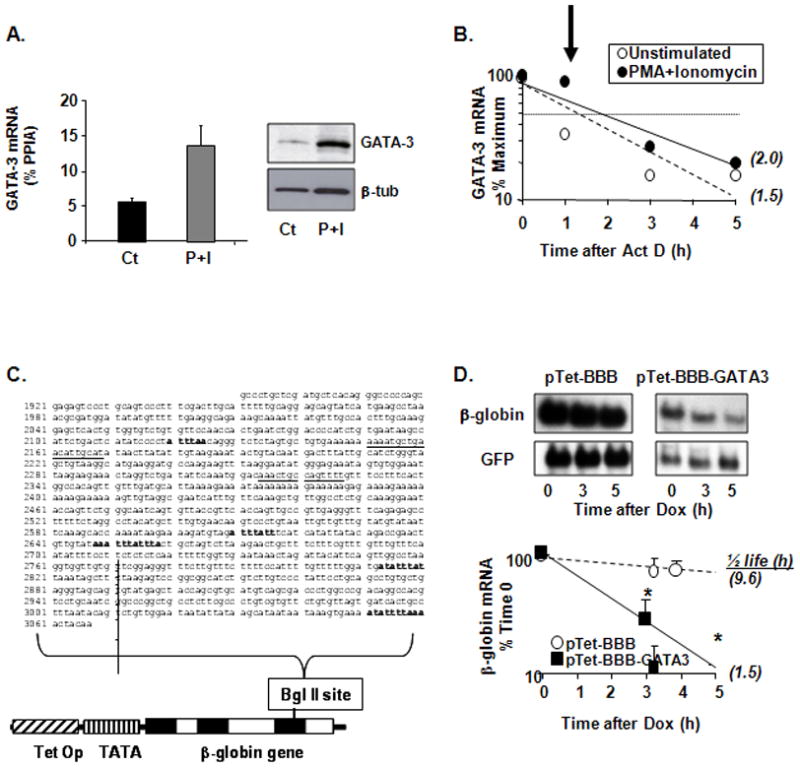

To test whether T-cell activation would regulate GATA-3 expression through posttranscriptional pathways, we first examined the expression and decay rate of GATA-3 mRNA turnover in human, in vitro Th2-skewed cells. Cells were left unchallenged, or were restimulated for 3 h with PMA (50 ng/ml) and the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (250 ng/ml), alone or in combination. Steady-state levels of GATA-3 mRNA were increased by cell treatment, as well as GATA-3 protein levels, as detected by Western blot (Figure 1A). To measure mRNA turnover, stimulated cells were either collected at the end of the stimulation (as time 0), or further treated with the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D (Act D, 3 μg/ml) for 1, 3 or 5 h. Total RNA was isolated for analysis of GATA-3 mRNA expression by RT-real-time PCR. Results were normalized to housekeeping mRNA levels and expressed as % of maximum (i.e., mRNA at time 0). GATA-3 mRNA was detectable at baseline (CT = 23.5) and displayed a fast turnover, as only 33% of the initial pool was detectable within 1 h from transcriptional termination (half-life 1.5 h; Figure 1B). Treatment with PMA plus ionomycin induced a stimulus-dependent stabilization of the GATA-3 mRNA, with 53% of the mRNA still detectable at the same 1-h time point (half-life: 2 h). The stabilizing effect was transient and peaked soon after activation, since the decay curves showed at later time points smaller differences between unstimulated and activated cells. The flattening of the decay curve at the later experimental time points could also be due to cell type- and time-dependent toxicity related to the Act D, as after longer incubation with this drug there is an increasing percentage of non-viable T cells that do not process RNA efficiently. However, stimulus-induced stabilization of GATA-3 mRNA occurred in parallel with that of another known HuR mRNA target, IL-13 (27).

Figure 1. Stabilization of GATA-3 mRNA in stimulated peripheral blood T cells: role of GATA-3 3′UTR.

(A) Detection of GATA-3 mRNA levels by real time RT-PCR (mean ± SEM of n = 9, *p<0.05 vs. control) and GATA-3 protein by Western blot from cultured peripheral blood T cells untreated or challenged with PMA (20 ng/ml) and the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (Iono, 250 ng/ml) for 3 h. (B) Kinetics of GATA-3 mRNA decay from cultured peripheral blood T cells assessed by real time RT-PCR (mean of n = 2) in Act D assay. Cells were left untreated or challenged with PMA and Iono as described above, and were then harvested (as time 0) or further treated with Act D (3 μg/ml) for 1, 3 or 5 h. The arrow indicates the time point at which the combined treatment markedly stabilized GATA-3 mRNA. In parenthesis: GATA-3 mRNA half-life, calculated as the time required for the transcript to decrease to 50% of its initial abundance. (C) The full 3′UTR of the GATA-3 mRNA (common to transcript variants 1 (NM_001002295) and 2 (NM_002051). AU-rich elements are bolded; underlined are other putative HuR recognition sites as described (29). This fragment was subcloned in the unique BglII site of the pTet-BBB reporter construct. Exons and introns in the rabbit β-globin gene are shown in white and black. TetOp, tetracycline operator sequences, TATA, minimal CMV promoter. (D) Representative Northern blot and, below, densitometric analysis (mean ± SEM of n = 3) of β-globin mRNA expression in H2 cells transfected with the indicated plasmids. Cytoplasmic RNA was harvested at baseline (time 0) or at the indicated times following transcriptional shut-off induced by doxycycline (Dox). In parenthesis: β-globin mRNA half-life, calculated as the time required for the transcript to decrease to 50% of its initial abundance. * p < 0.05 β-globin mRNA in pTet-BBB-GATA-3-transfected cells compared to pTet-BBB-transfectants.

Cis-elements and trans-factors involved in GATA-3 posttranscriptional regulation

We employed established models for the study of the cis-element (the ARE) and the trans-factor (HuR) that we hypothesized to be involved in the posttranscriptional regulation of GATA-3. As in the case of IL-13 and IL-4 (14, 27), the 3′-UTR of GATA-3 mRNA harbors “class 1” AREs (47), with four scattered AUUUA pentamers embedded in an A- and U-rich milieu. In addition, it displays two adjacent AUUUA pentamers and two additional described HuR consensus sites (29), (Figure 1C). We subcloned the full-length GATA-3 3′-UTR in a Tet-off promoter-driven reporter system expressing the rabbit β-globin gene (pTet-BBB) (38, 48). The construct expressing the GATA-3 UTR-bearing transcript, and its parent vector as control, were transiently transfected in parallel in H2 cells, which are stably transfected with the rTet factor (38), together with a GFP expression vector for normalization. The turnover of the β-globin mRNA, assessed by Northern blot after transcriptional shut-off with doxycycline (DOX; Figure 1D–E), was markedly accelerated by the insertion of the GATA-3 3′UTR, displaying a half-life of 1.5 h compared to 9.6 h in cells transfected with the control vector. The HuR-mediated stabilization of GATA-3 mRNA appears to rely on cell activation, while in unstimulated condition; the GATA-3 mRNA is fairly labile (Figure 1B). Therefore the behavior observed with the chimeric mRNA reporter supports the hypothesis that GATA-3 can be regulated at the level of mRNA turnover through its 3′UTR, and is consistent with the rapid decay observed for the endogenous GATA-3 mRNA in unstimulated Th2 cells.

As the GATA-3 mRNA displays dynamic changes in decay after cell activation, including a transient stabilization, we investigated whether HuR associated with endogenous GATA-3 transcript. We performed IP of mRNP isolated from Jurkat T cells either unstimulated or treated with PMA and ionomycin for 3 hr, using a monoclonal anti-HuR (3A2) or an isotype-matched antibody. Western blot analysis confirmed that the IP with anti-HuR was specific (Figure 2A) and using real-time PCR, GATA-3 mRNA was identified consistently enriched in the immunoprecipitated mRNA pool obtained with anti-HuR over the isotype control Ab-immunoprecipitates (Figure 2A). The same mRNA pool, previously studied for additional HuR targets, showed high enrichment for IL-13 in the HuR-IP as well as lack of specific association for the GAPDH mRNA (27). In unstimulated Jurkat cells, the difference of 6 cycles for GATA-3 detection between the HuR-dependent and the mock IP (ΔCT) indicated a 2-(6) = 64-fold enrichment in GATA-3 in the HuR IP. GATA-3 mRNA was enriched as well in stimulated cells compared to the control IP, with a ΔCT of 3 cycles, although levels of endogenous HuR did not change following cell stimulation (data not shown).

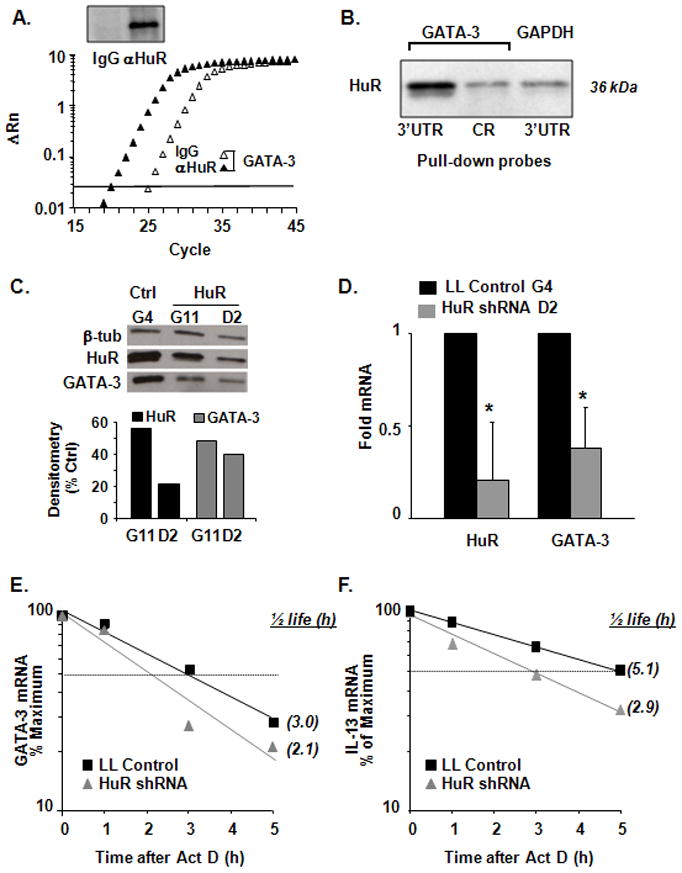

Figure 2. Functional association of HuR with GATA-3 mRNA.

(A) RNP-IP assay for detection of GATA-3 mRNA in Jurkat cell cytoplasmic extracts immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-HuR or isotype-matched Ab. Upper Panel: Western blot analysis showing specific HuR detection in the IP samples. Lower Panel: real-time PCR plot showing GATA-3 mRNA enrichment in the anti-HuR IP samples compared to isotype-matched IgG Ab (representative of n = 3). (B) HuR protein expression by Western blot after biotin pull-down assay (representative of n = 3) with biotinylated transcripts spaning the GATA-3 3′UTR and coding region (CR) and the 3′UTR of GAPDH, used as negative control. (C) Western blot (representative of n = 2) of HuR, GATA-3 and β-tubulin (as loading control) expression in Jurkat cell clones (G11 and D2) stably infected with HuR shRNA lentivirus knock-down and in control clone G4, stably infected with empty vector. Bargraphs represent the mean densitometric analysis normalized to β-tubulin. (D) Mean ± SEM (n=3) of HuR and GATA-3 mRNA steady-state levels as measured by real-time PCR in Jurkat cell clones G4 (control) and D2 (HuR shRNA). (E) GATA-3 and (F) IL-13 mRNA decay measured by real-time PCR in G4 and D2 cells after treatment with Act D (n = 3; p < 0.05 for half-life for both genes).

We further validated the interaction of HuR with the 3′UTR of GATA-3 mRNA using a biotin pull-down approach (Figure 2B). In vitro transcribed, biotinylated transcripts spanning the coding region or the full-length 3′-UTR of GATA-3, or the full-length 3′UTR of GAPDH (used as negative control) were incubated with cytoplasmic protein lysates from Jurkat cells. After pull-down with streptavidin-coated beads, HuR was robustly detected by Western blot in the samples precipitated by the GATA-3 3′UTR biotinylated probe, while the association with the coding region was comparable to the background obtained by the negative control, the biotinylated GAPDH 3′UTR.

In order to demonstrate the functional outcome of the interaction between HuR and GATA-3 mRNA, we established Jurkat cells stably transduced with a lentiviral shRNA targeting HuR expression. Individual clones with differing levels of HuR were established by limiting dilution techniques. Two representative individual Jurkat clones, G11 and D2, showed reduced levels of HuR protein (by 56% and 21%, respectively), as compared with Lentilox control (Figure 2C). The levels of β-tubulin, whose mRNA does not bind to HuR, were not affected. The levels of GATA-3 protein in the same clones were reduced in proportional fashion, by 49% (G11) and 40% (D2) (Figure 2C), suggesting that HuR association with GATA-3 mRNA could be functionally involved in regulating GATA-3 protein levels. We then compared steady-state GATA-3 mRNA levels, as well as transcript stability in Act D experiments between Lentilox control and D2 clone Jurkat cells. GATA-3 mRNA levels decreased by 60% in D2 cells (Figure 2D), with a small but significant reduction of the mRNA half-life (Figure 2E, from 3.0 h in the control to 2.1 h in D2 cells, n=3 p < 0.05). The mRNA decay of the HuR target IL-13 (27) was also affected, with a significantly decreased half-life in D2 cells compared to Lentilox control cells (Figure 2F, t1/2=2.9 h versus 5.1 h, n=3 p < 0.05). Comparable reductions in GATA-3 protein, as well as of mRNA steady-state levels and half-life were obtained using an alternative HuR siRNA transiently transfected in Jurkat cells (Supplemental Figure 1 A–C).

HuR siRNA knock down results in reduced GATA-3 expression in human Th2 polarized T and memory cells

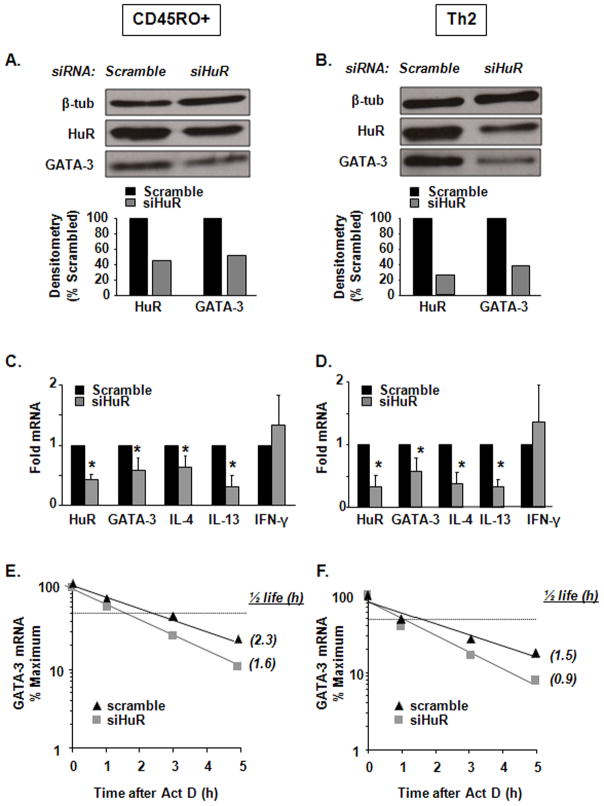

To further probe the relevance of HuR in human T cell responses, we examined Gata-3 expression in human peripheral T cells in which HuR was silenced using HuR specific siRNA. Silencing of HuR was implemented in both CD45RO+ memory T cells and in Th2-skewed CD4+ T cells, where levels of HuR were decreased by 67% and 82%, respectively (Figure 3A and 3B). Levels of GATA-3 protein were reduced as well by 57% and 71%, respectively (Figure 3A and 3B). In these cells, steady-state mRNA levels of GATA-3, IL-4 and IL-13 - but not IFN-γ were significantly reduced as well, compared to cells transfected with the scrambled siRNA control (Figure 3C and 3D). HuR silencing also consistently reduced GATA-3 transcript stability in both cell types (Figures 3E and 3F), though to a lesser extent than that documented in Jurkat cells (Figures 2 and S1).

Figure 3. HuR silencing in human CD45RO+ memory T cells and in Th2 cells affects GATA-3 and Th2 cytokine levels.

(A) Western blot (representative of n = 2) of HuR, GATA-3 and β-tubulin protein expression in human CD45RO+ memory T cells and (B) Th2-polarized cells transfected by specific HuR siRNA or a scrambled siRNA control. (C) mRNA steady-state levels of HuR, GATA-3, IL-4, IL-13, IFN-γ measured by real-time PCR in human memory T cells or (D) in human Th2 cells (Mean ± SEM n=3, p<0.05). (E) GATA-3 mRNA decay measured by real-time PCR after treatment with Act D in memory T cells and (E) Th2 cells transfected with HuR siRNA or scrambled control (n = 4; p < 0.05 for half-life). Each experiment (CD45RO+ and Th2 polarization) was performed independently four times (total of eight separate experiments). Western analysis in (A) was performed two times; real time PCR in (C) and (D) three times and actinomycin D in (E) and (F) was performed four times.

Activated transgenic T cells express increased GATA-3 mRNA and protein levels

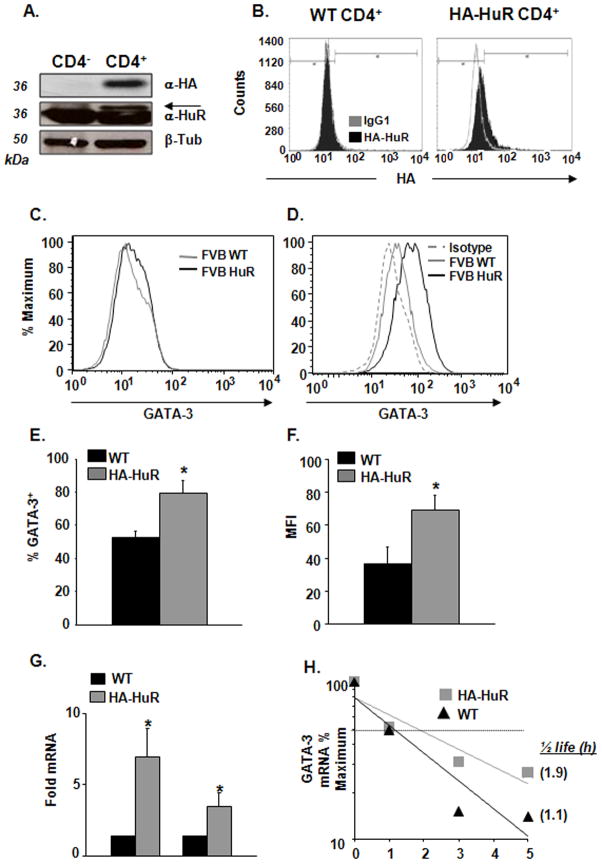

To further investigate the functional outcome of HuR association with GATA-3 mRNA, we generated a transgenic mouse model of HuR overexpression, in which HA-tagged HuR was expressed in a CD4+ T cell-restricted fashion. CD4+ T cells purified from transgenic mouse spleens selectively expressed the exogenous HA-HuR (Figure 4A), which was readily detectable either with an anti-HA Ab or with an anti-HuR Ab, together with the endogenous form. Flow cytometric and Western analysis estimated that CD4+ T cells from transgenic mice expressed approximately 120% of HuR levels present in WT littermates (Figure 4B). No abnormalities were seen in lymphoid or other organs in the HA-HuR transgenic mice (data not shown).

Figure 4. Increased GATA-3 expression in activated murine Th2 cells over-expressing HuR.

(A) CD4+ cells purified from FVB-HA-HuR transgenic mouse spleens (HA-HuR CD4+) expressing HA-HuR, as indicated by Western blot analysis using anti-HA Ab (upper panel) or anti-HuR (middle panel; arrow indicates the exogenous HuR). Lower panel, β-tubulin. Representative of n = 2. (B) CD4+ T cells from FVB-WT mice do not express HA (left panel). CD4+ T cells from FVB-HA HuR mouse spleens express HA-HuR (right panel), as indicated by intracellular HA staining compared to isotype control (IgG1). Representative of n = 2. (C) GATA-3 protein expression by FACS analysis in activated, unpolarized CD4+ T cells and in (D) activated Th2-polarized cells from FVB-HA HuR transgenic mouse and FVB-WT mice. (E) Increased percentages of GATA-3+ cells in Th2-polarized cells overexpressing HuR compared to WT control, as analyzed by FACS analysis. (*p <0.05) (F) Increased GATA-3-associated mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) in Th2-polarized cells overexpressing HuR. (Mean ± SEM of n = 3, *p < 0.05). (G) HuR and GATA-3 mRNA steady-state levels measured by real-time PCR in HA-HuR transgenic and WT-derived Th2 cells. (Mean ± SEM n=3, *p < 0.05). (H) GATA-3 mRNA decay measured by real-time PCR in HA-HuR transgenic and WT-derived Th2 cells after treatment with Act D (n = 3, p< 0.05 for GATA-3 mRNA half-life in HA-HuR cells vs. WT).

Unpolarized CD4+ T cells from HA-HuR transgenic and wild type (WT) littermates were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 for five days. GATA-3 expression was only marginally increased in CD4+ T cells from transgenic animals as compared to WT controls (Figure 4C). In contrast, when naïve CD4+ T cells from HA-HuR mice were cultured under Th2-polarizing conditions, we observed a significant increase in GATA-3 protein expression, as compared with WT littermates (Figure 4D). Th2-polarized cells from HA-HuR transgenic animals displayed greater frequencies of GATA-3+ cells (80% vs. 53% in WT), as well as significantly higher GATA-3-associated mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) (70% vs. 36.5% in WT, p<0.05) (Figures 4E and 4F). Furthermore, the GATA-3 mRNA steady-state levels and stability were consistently increased in Th2 HA-HuR-derived cells compared to cells from WT (n=3, half life 1.9 h vs. 1.1 h, respectively, p<0.05) (Figure 4G and 4H). Overall, these data indicate that a relatively modest increases in HuR levels brought by overexpression (20% higher that WT, Figure 4B) led to a significant increase in GATA-3 mRNA levels and stability and ultimately, of GATA-3 protein levels. We also confirmed, using the biotin pull down assay, that HuR binds to murine GATA-3 (Supplemental Figure 2A), and that this association is mediated by specific ARE-bearing sequences. In fact, using site-directed mutagenesis, we altered the sequence of GATA-3 3′UTR as indicated in Methods. This strategy abrogated HuR binding to murine GATA-3 3′UTR (Supplemental Figure 2B). Taken together, these data suggest that HuR is capable of regulating GATA-3 gene expression in mouse CD4+ T cells, and that this biological action is likely to be at least partially mediated by ARE-mediated changes in mRNA stability.

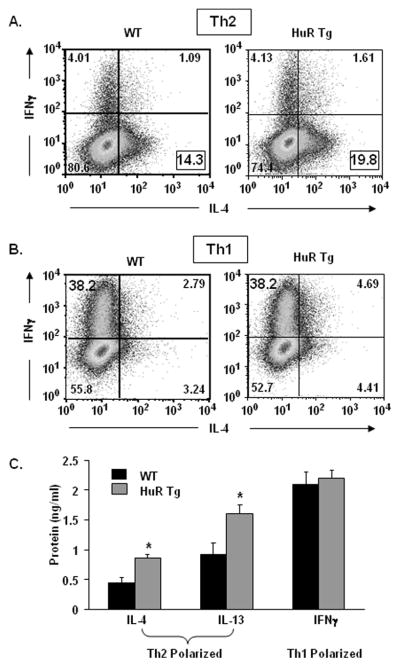

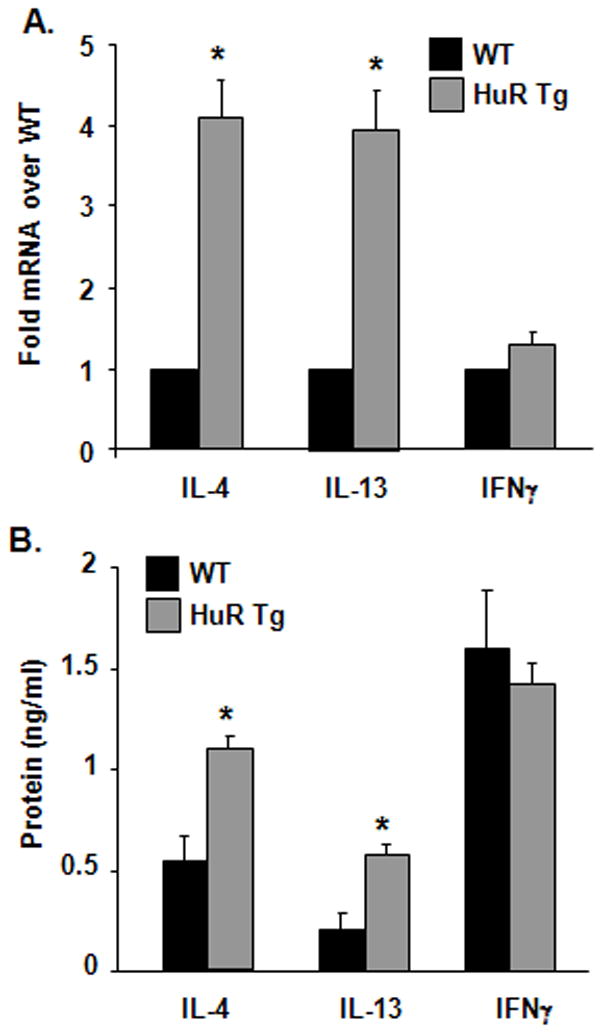

Activated splenocytes or polarized CD4+ Th2 cells from transgenic mice produce higher levels of Th2 cytokines

RBPs in general coordinate posttranscriptionally the expression of functionally related genes (9, 49), and in particular HuR has been shown to influence the GATA-3-regulated genes IL-4 and IL-13 (14, 26, 27). We asked whether higher expression levels of GATA-3 and HuR could affect levels of Th2 cytokines in both unpolarized and polarized T cells. Splenocytes from HA-HuR transgenic mice showed a significant increase in activation-induced IL-4 and IL-13, but not in IFNγ expression, at both the mRNA and protein level (Figure 5A, 5B) compared to WT. Levels of IL-5 were not reproducibly affected (data not shown). We then polarized naïve CD4+ T cells under either Th1 or Th2 conditions (Figure 6). While under Th1 conditions there was no appreciable differences among IFN-γ-or IL-4-producing cells between transgenic and WT mice, Th2 polarization led to a small but consistent increase in the frequencies of IL-4-secreting cells, ranging in 6 experiments from 4% to 16% (mean ± SEM: 7.4% ± 2.3%, p = 0.013, representative plot shown in Figure 6A), while the frequencies of IFN-γsecreting cells in Th1 cells were unchanged (Figure 6B). Furthermore, in agreement with the data generated in unpolarized cells (Figure 5), HA-HuR CD4+ transgenic Th2 cells secreted significantly higher amounts of IL-4 and IL-13 than the WT-derived Th2 cells, while IFN-γ secretion from Th1-polarized cells did not change in the two groups (Figure 6C). Taken together, these results indicate that in parallel with the increase in GATA-3 levels, HuR overexpression can lead to significant increases in Th2 cytokine production, as previously shown in vitro (14, 27).

Figure 5. Increased IL-4 and IL-13 levels in HuR-overexpressing mouse splenocytes.

(A) Cytokine mRNA measured by real-time PCR and (B) protein levels assessed by ELISA from splenocytes derived from FVB-HA HuR transgenic mouse and WT control activated with PMA and ionomycin. Mean ± SEM of n = 3. (*p < 0.005 compared to WT)

Figure 6. Increased frequencies of IL-4-expressing cells and increased IL-4 and IL-13 secretion in Th2-polarizing cultures of CD4+ T cells overexpressing HuR.

(A) Scatter plot of cytokine-associated fluorescence in Th2- (A) and Th1-polarized cells (B), showing an increased frequency of IL-4+ cells, but similar frequency of IFN-γ+ cells in FVB transgenic cells (HuR Tg) compared to WT cells. Plots representative of n = 6. (C) Increased secretion of IL-4 and IL-13 in Th2-polarized CD4+ T cells, but not of IFNγ in Th1-polarized cells from FVB transgenic mice compared to WT mice. Mean ± SEM of n = 5, *p < 0.05.

Discussion

The molecular mechanisms involved in Th2 differentiation and maintenance have been so far only partially understood. While much has been learned about the transcriptional programs which determine naïve CD4+ T-cell fate, very little is known about the role of posttranscriptional gene regulation in controlling T-cell lineage commitment. The transcription factor GATA-3 is considered to be one of the most important genes involved in the process of Th2 polarization, as it has been described to be necessary and sufficient to drive the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cell into the Th2 lineage (50).

Previously, we and others have described the cloning of HuR and demonstrated that its regulation is cell–cycle-dependent (16, 18, 51). Activation of T cells results in 10–14 fold increases in total cellular HuR levels (16), as well as its translocation from the nucleus into the cytoplasm, which correlates with its functional activation (12, 14–17). HuR has been subsequently shown to play an important role in regulation of many genes involved in Th2-driven inflammatory diseases, such as asthma (11, 14–16, 27).

Genes affecting Th2-polarized function, such as GATA-3, IL-4 and IL-13, harbor in their 3′UTR AREs and other sequences regulating mRNA turnover and translation, which are highly enriched in immune genes. RBPs like HuR, which bind the ARE in the 3′UTR regions of these genes, can powerfully affect the rates of mRNA transport in the cytoplasm, transcript stability and/or translation. Since HuR is known to regulate posttranscriptionally the expression of IL-4 and IL-13 by increasing the stability of their mRNA (14, 27), we hypothesized that it may also regulate GATA-3 expression as well, via interacting with specific AREs present in its 3′UTR, as part of a global, coordinate action on the Th2 phenotype. Our results demonstrate that the stability of GATA-3 mRNA is increased, along with its steady-state and with protein levels, in stimulated human and murine Th2-skewed cells, and that the prolonged mRNA turnover is modified accordingly in conditions of relative HuR overexpression and silencing, both in vitro and ex vivo (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, S1). In conjunction with the data showing association of HuR with both endogenous and synthetic GATA-3 mRNA shown in Figure 2 and S1, we provide strong evidence indicating that HuR directly regulates GATA-3, by association with its 3′UTR and stabilization of its transcript. Along the same lines, HuR silencing in Jurkat cells reduced GATA-3 mRNA steady-state levels and stability, as well as protein levels, similarly to what observed for GATA-3 mRNA and protein after HuR silencing in the human mammary epithelial cell line MCF-7 (52). We have also recently demonstrated by HuR RIP-Chip that GATA-3 mRNA is a HuR target in MCF-7 estrogen positive breast cancer (39). Of larger potential relevance to human disease, HuR silencing obtained in human CD45RO+ memory T cells as well as in human Th2 polarized cells significantly decreased GATA-3 mRNA and protein levels.

As a corollary to the data generated in human cells, even relatively modest levels of HuR overexpression generated in our transgenic mouse model resulted in increased GATA-3 mRNA steady-state and stability, and in increased GATA-3 protein expression. Importantly, increased levels of GATA-3 protein, as well as that of Th2 cytokine secretion, were paralleled in the transgenic model by a lack of effect on IFN-γ secretion in either Th1- or Th2-polarized cells. Interestingly, GATA-3 is the most highly expressed transcription factor in normal mammary epithelium as is required for its maintenance (53–55).

Exogenous changes in the levels of HuR in our experimental models confirmed that this factor regulates GATA-3 mRNA stability. In general, the decay profiles obtained with transcriptional inhibitor like Actinomycin D are better suited to document the occurrence of relative changes in decay induced by cell stimulation or by altered levels of regulatory factors – HuR in this study - rather than tracing the exact kinetic of decay, as there are limitations due to the toxicity of Act D (56). Overall, our mRNA decay data show in different experimental settings (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and S1) a significant, consistent stimulus-dependent change in GATA-3 mRNA stability that is susceptible of HuR regulation. However, we cannot exclude that HuR may regulate the overall levels of GATA-3 by other concurrent mechanisms. In fact, besides its positive effect on mRNA stabilization, HuR has been found to modulate, for other T cell targets, either cytoplasmic accumulation or translation (2, 14, 15, 57, 58).

While our results reveal a direct, functional interaction of HuR with GATA-3 mRNA, it remains to be established to what extent HuR participates in the regulation of Th2 polarization and function via controlling GATA-3 expression, as opposed to its direct role on IL-4 and IL-13 expression. Taken together, the results of our study highlight the central importance that HuR may play in CD4+ T-cell differentiation and function through the coordinated regulation of its targets, and points at posttranscriptional regulation as a critical, yet still largely uncharacterized component of T cell gene regulation.

In future studies, it will be important to perform more specific, targeted deletions of HuR in specific T cell subsets. Such approaches will help to more fully elucidate the impact of posttranscriptional gene regulation in phenotype initiation and maintenance during T cell differentiation. These efforts can potentially shed light on the mechanisms of Th2-driven inflammatory diseases such as asthma.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- Act D

actinomycin D

- ARE

adenylate-uridylate rich region

- ARE-BP

ARE-binding protein

- HA

hemagglutinin

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- RBP

RNA-binding protein

- mRNP-IP

immunoprecipitation of messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI080870-01and R21AI079341-01 (Dr. Atasoy) and AI060990-01A1 (Dr. Stellato).

References

- 1.Cheadle C, Fan J, Cho-Chung YS, Werner T, Ray J, Do L, Gorospe M, Becker KG. Control of gene expression during T cell activation: alternate regulation of mRNA transcription and mRNA stability. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghavan A, Dhalla M, Bakheet T, Ogilvie RL, Vlasova IA, Khabar KS, Williams BR, Bohjanen PR. Patterns of coordinate down-regulation of ARE-containing transcripts following immune cell activation. Genomics. 2004;84:1002–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghavan A, Ogilvie RL, Reilly C, Abelson ML, Raghavan S, Vasdewani J, Krathwohl M, Bohjanen PR. Genome-wide analysis of mRNA decay in resting and activated primary human T lymphocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:5529–5538. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vavassori S, Covey LR. Post-transcriptional regulation in lymphocytes: the case of CD154. RNA Biol. 2009;6:259–265. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.3.8581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson P. Post-transcriptional control of cytokine production. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:353–359. doi: 10.1038/ni1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keene JD. RNA regulons: coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilusz CJ, Wilusz J. Bringing the role of mRNA decay in the control of gene expression into focus. Trends in Genetics. 2004;20:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khabar KS. The AU-rich transcriptome: more than interferons and cytokines, and its role in disease. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:1–10. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keene JD, Tenenbaum SA. Eukaryotic mRNPs may represent posttranscriptional operons. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinman MN, Lou H. Diverse molecular functions of Hu proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raghavan A, Robison RL, McNabb J, Miller CR, Williams DA, Bohjanen PR. HuA and tristetraprolin are induced following T cell activation and display distinct but overlapping RNA binding specificities. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47958–47965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JG, Collinge M, Ramgolam V, Ayalon O, Fan XC, Pardi R, Bender JR. LFA-1-dependent HuR nuclear export and cytokine mRNA stabilization in T cell activation. J Immunol. 2006;176:2105–2113. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papadaki O, Milatos S, Grammenoudi S, Mukherjee N, Keene JD, Kontoyiannis DL. Control of thymic T cell maturation, deletion and egress by the RNA-binding protein HuR. J Immunol. 2009;182:6779–6788. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yarovinsky TO, Butler NS, Monick MM, Hunninghake GW. Early Exposure to IL-4 Stabilizes IL-4 mRNA in CD4+ T Cells via RNA-Binding Protein HuR. J Immunol. 2006;177:4426–4435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seko Y, Azmi H, Fariss R, Ragheb JA. Selective Cytoplasmic Translocation of HuR and Site-specific Binding to the Interleukin-2 mRNA Are Not Sufficient for CD28-mediated Stabilization of the mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33359–33367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atasoy U, Watson J, Patel D, Keene JD. ELAV protein HuA (HuR) can redistribute between nucleus and cytoplasm and is upregulated during serum stimulation and T cell activation. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 21):3145–3156. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.21.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu YZ, Di Marco S, Gallouzi I, Rola-Pleszczynski M, Radzioch D. RNA-binding protein HuR is required for stabilization of SLC11A1 mRNA and SLC11A1 protein expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8139–8149. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8139-8149.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma WJ, Cheng S, Campbell C, Wright A, Furneaux H. Cloning and characterization of HuR, a ubiquitously expressed Elav-like protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8144–8151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean JL, Wait R, Mahtani KR, Sully G, Clark AR, Saklatvala J. The 3′ untranslated region of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA is a target of the mRNA-stabilizing factor HuR. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:721–730. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.721-730.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ming XF, Stoecklin G, Lu M, Looser R, Moroni C. Parallel and independent regulation of interleukin-3 mRNA turnover by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5778–5789. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5778-5789.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixon DA, Tolley ND, King PH, Nabors LB, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM. Altered expression of the mRNA stability factor HuR promotes cyclooxygenase-2 expression in colon cancer cells. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1657–1665. doi: 10.1172/JCI12973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg-Cohen I, Furneauxb H, Levy AP. A 40-bp RNA element that mediates stabilization of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by HuR. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13635–13640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez-Pascual F, Hausding M, Ihrig-Biedert I, Furneaux H, Levy AP, Forstermann U, Kleinert H. Complex contribution of the 3′-untranslated region to the expressional regulation of the human inducible nitric-oxide synthase gene. Involvement of the RNA-binding protein HuR. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26040–26049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910460199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atasoy U, Curry SL, López de Silanes I, Shyu AB, Casolaro V, Gorospe M, Stellato C. Regulation of Eotaxin Gene Expression by TNF and IL-4 Through Messenger RNA Stabilization: Involvement of the RNA-binding protein HuR. J Immunol. 2003;171:4369–4378. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghosh M, Aguila HL, Michaud J, Ai Y, Wu MT, Hemmes A, Ristimaki A, Guo C, Furneaux H, Hla T. Essential role of the RNA-binding protein HuR in progenitor cell survival in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3530–3543. doi: 10.1172/JCI38263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler NS, Monick MM, Yarovinsky TO, Powers LS, Hunninghake GW. Altered IL-4 mRNA stability correlates with Th1 and Th2 bias and susceptibility to hypersensitivity pneumonitis in two inbred strains of mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:3700–3709. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casolaro V, Fang X, Tancowny B, Fan J, Wu F, Srikantan S, Asaki SY, De Fanis U, Huang SK, Gorospe M, Atasoy UX, Stellato C. Posttranscriptional regulation of IL-13 in T cells: role of the RNA-binding protein HuR. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:853–859 e854. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang JL, Gao PS, Mathias RA, Yao TC, Chen LC, Kuo ML, Hsu SC, Plunkett B, Togias A, Barnes KC, Stellato C, Beaty TH, Huang SK. Sequence variants of the gene encoding chemoattractant receptor expressed on Th2 cells (CRTH2) are associated with asthma and differentially influence mRNA stability. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2691–2697. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez de Silanes I, Zhan M, Lal A, Yang X, Gorospe M. Identification of a target RNA motif for RNA-binding protein HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2987–2992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho IC, Tai TS, Pai SY. GATA3 and the T-cell lineage: essential functions before and after T-helper-2-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes PJ. Role of GATA-3 in allergic diseases. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:330–334. doi: 10.2174/156652408785160952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy KM. Fate vs choice: the immune system reloaded. Immunol Res. 2005;32:193–200. doi: 10.1385/IR:32:1-3:193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson P. Post-transcriptional regulons coordinate the initiation and resolution of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:24–35. doi: 10.1038/nri2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul WE. What determines Th2 differentiation, in vitro and in vivo? Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:236–239. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsukura S, Stellato C, Georas SN, Casolaro V, Plitt JR, Miura K, Kurosawa S, Schindler U, Schleimer RP. Interleukin-13 upregulates eotaxin expression in airway epithelial cells by a STAT6-dependent mechanism. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:755–761. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.6.4351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heller NM, Matsukura S, Georas SN, Boothby MR, Rothman PB, Stellato C, Schleimer RP. Interferon-{gamma} inhibits STAT6 signal transduction and gene expression in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004:2004–0195OC. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0195OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Fanis U, Mori F, Kurnat RJ, Lee WK, Bova M, Adkinson NF, Casolaro V. GATA3 up-regulation associated with surface expression of CD294/CRTH2: a unique feature of human Th cells. Blood. 2007;109:4343–4350. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin S, Wang W, Wilson GM, Yang X, Brewer G, Holbrook NJ, Gorospe M. Down-regulation of cyclin D1 expression by prostaglandin A(2) is mediated by enhanced cyclin D1 mRNA turnover. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7903–7913. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.7903-7913.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calaluce R, Gubin MM, Davis JW, Magee JD, Chen J, Kuwano Y, Gorospe M, Atasoy U. The RNA binding protein HuR differentially regulates unique subsets of mRNAs in estrogen receptor negative and estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 10:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shyu AB, Belasco JG, Greenberg ME. Two distinct destabilizing elements in the c-fos message trigger deadenylation as a first step in rapid mRNA decay. Genes Dev. 1991;5:221–231. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heid CA, Stevens J, Livak KJ, Williams PM. Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res. 1996;6:986–994. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallouzi IE, Brennan CM, Stenberg MG, Swanson MS, Eversole A, Maizels N, Steitz JA. HuR binding to cytoplasmic mRNA is perturbed by heat shock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3073–3078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tenenbaum SA, Lager PJ, Carson CC, Keene JD. Ribonomics: identifying mRNA subsets in mRNP complexes using antibodies to RNA-binding proteins and genomic arrays. Methods. 2002;26:191–198. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang W, Caldwell MC, Lin S, Furneaux H, Gorospe M. HuR regulates cyclin A and cyclin B1 mRNA stability during cell proliferation. Embo J. 2000;19:2340–2350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawada S, Scarborough JD, Killeen N, Littman DR. A lineage-specific transcriptional silencer regulates CD4 gene expression during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 1994;77:917–929. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilusz CJ, Wormington M, Peltz SW. The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:237–246. doi: 10.1038/35067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu N, Loflin P, Chen CY, Shyu AB. A broader role for AU-rich element-mediated mRNA turnover revealed by a new transcriptional pulse strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:558–565. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keene JD. Ribonucleoprotein infrastructure regulating the flow of genetic information between the genome and the proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7018–7024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111145598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng W, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan XC, Steitz JA. HNS, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling sequence in HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15293–15298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Licata LA, Hostetter CL, Crismale J, Sheth A, Keen JC. The RNA-binding protein HuR regulates GATA3 mRNA stability in human breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:55–63. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kouros-Mehr H, Bechis SK, Slorach EM, Littlepage LE, Egeblad M, Ewald AJ, Pai SY, Ho IC, Werb Z. GATA-3 links tumor differentiation and dissemination in a luminal breast cancer model. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kouros-Mehr H, Kim JW, Bechis SK, Werb Z. GATA-3 and the regulation of the mammary luminal cell fate. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kouros-Mehr H, Slorach EM, Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. GATA-3 maintains the differentiation of the luminal cell fate in the mammary gland. Cell. 2006;127:1041–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ysla RM, Wilson GM, Brewer G, Lynne EM, Megerditch K. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 2008. Assays of Adenylate Uridylate-Rich Element-Mediated mRNA Decay in Cells; pp. 47–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Millard SS, Vidal A, Markus M, Koff A. A U-rich element in the 5′ untranslated region is necessary for the translation of p27 mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5947–5959. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.5947-5959.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prechtel AT, Chemnitz J, Schirmer S, Ehlers C, Langbein-Detsch I, Stulke J, Dabauvalle MC, Kehlenbach RH, Hauber J. Expression of CD83 Is Regulated by HuR via a Novel cis-Active Coding Region RNA Element. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10912–10925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.