Abstract

Background and aims

Abdominal aortic calcium (AAC) predicts future cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and all-cause mortality independent of CVD risk factors. The standard AAC score, the Agatston, up-weights for greater calcium density, and thus models higher calcium density as associated with increased CVD risk.

We determined associations of CVD risk factors with AAC volume and density (separately).

Methods

In a multi-ethnic cohort community living cohort, we used abdominal computed tomography scans to measure AAC volume and density. Multivariable linear regression was used to determine the period cross-sectional independent associations of CVD risk factors with AAC volume and AAC density in participants with prevalent AAC.

Results

Among 1413 participants with non-zero AAC scores, the mean age was 65 ± 9 years, 52% were men, 44% were European-, 24% were Hispanic-, 18% were African-, and 14% were Chinese Americans (EA, HA, AA, and CA respectively). Median (interquartile range, IQR) for AAC volume was 628 mm3 (157–1939 mm3), and mean AAC density was 3.0 ± 0.6. Compared to EA, each of HA, AA, and CA had lower natural log (ln) AAC volume, but higher AAC density. After adjustments for AAC density, older age, ever smoking history, higher systolic blood pressure, elevated total cholesterol, reduced HDL cholesterol, statin and anti-hypertensive medication use, family history of myocardial infarction, and alcohol consumption were significantly associated with higher ln(AAC volume). In contrast, after adjustments for ln(AAC volume), older age, ever smoking history, higher BMI, and lower HDL cholesterol were significantly associated with lower AAC density.

Conclusions

Several CVD risk factors were associated with higher AAC volume, but lower AAC density. Future studies should investigate the impact of calcium density of aortic plaques in CVD.

Keywords: Abdominal aortic calcium, Agatston calcium score, Cardiovascular disease risk factors, Coronary artery calcium, Density calcium score, Volume calcium score

Introduction

Abdominal aortic calcium (AAC) and coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores similarly predict future cardiovascular disease (CVD) events independent of CVD risk factors, but only AAC predicts all-cause mortality in mutually adjusted models.1–3 The Agatston method, used as the standard for AAC and CAC scores, up-weights plaque for higher calcium density, and thus models density as positively associated with CVD risk. However, evidence exists that more densely calcified coronary artery plaques may pose a lower CVD risk than less densely calcified plaques.4–6 Researches have reported that among patients with plaque measured from coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA), incident CVD was lowest among patients with only calcified plaques, compared to those with both calcified and non-calcified, and those with only non-calcified plaques.4,5 Researches have also reported that for a given CAC volume, higher CAC density was protective for CVD events.6 To date, most studies quantifying AAC and CAC for CVD risk prediction have used the Agatston score, which models a positive association between CVD risk factors and calcium density. We investigate this model by determining independent associations of CVD risk factors with AAC volume and density (separately).

Materials and methods

Study sample

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) is a multi-center, prospective cohort study designed to investigate the prevalence, risk factors, and CVD outcomes of individuals without clinical CVD at baseline. A detailed description of the study design, recruitment methods, examination components, and data collection has been published.7 In brief, participants included 6,814 men and women (age 45–84) of Caucasian, Hispanic-, African-, and Chinese-American descent, recruited between July 2000 and August 2002 from 6 U.S field centers; New York, NY; Baltimore, MD; Winston-Salem, NC; St Paul, MN; Chicago IL; and Los Angeles, CA. Signed informed consent was obtained for all participants, and institutional review board approval was obtained for all participating institutions. During follow up visits between August 2002 and September 2005, a randomly selected subsample of 2,202 MESA participants were invited to participate in an ancillary study that aimed to determine the presence and extent of AAC. Of these, 2,172 agreed to participate. Individuals were excluded if they were pre-menopausal, or had a recent (within prior 6 months) abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan. This left 1,970 participants who underwent abdominal CT scans to measure AAC. Since a density score only has meaning in those with non-zero calcium volume, this study was limited to 1,413 participants with prevalent AAC (Agatston scores > 0).

Calcium measurement

The methodology for acquisition and interpretation for AAC has previously been described.8 Abdominal images were obtained using multi-detector CT scanners at Columbia University, Wake Forest University, and University of Minnesota field centers (Sensation 64 [Siemens, Malvern, Pennsylvania] and GE Lightspeed [GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin], Siemens S4 Volume Zoom, and Siemens Sensation 16, respectively). Electron-beam CT scanners were utilized at Northwestern University and University of California, Los Angeles (Imatron C-150, Imatron Inc., South San Francisco, California). Images were reconstructed in a 35 cm field of view with a slice thickness of 3 mm (EBCT scanners) or 2.5mm (multi-detector scanners). For equal comparisons among participants with different abdominal aortic length, an 8cm segment proximal to the aortic bifurcation was used to quantify AAC.

AAC Agatston scores were quantified from abdominal CT scan slices by identifying an area of plaque defined by density Hounsfield Units (HU) greater than 130.9 The plaque area (mm2) was then multiplied by 1, 2, 3, or 4, depending on the plaque’s maximum density. Plaques with maximum density of 130 to 199 HU were multiplied by 1, those with 200 to 299 HU were multiplied by 2, those with 300 to 399 HU were multiplied by 3 and those with 400 HU or greater were multiplied by 4. AAC scores for all CT slices were then summed to produce the total plaque-specific scores. AAC volume (mm3) scores were the sum of all plaque areas multiplied by the CT slice thickness. The AAC density scores were calculated as: density = [Agatston] / [area, in mm2]. Where area, in mm2 = [volume, in mm3] / [CT scan slice thickness, in mm]. Thus density from these calculations represents a participant’s average multiplicative density factor (1–4 scale) derived from their original Agatston score.

Risk factor assessments

Participants were given standardized questionnaires at baseline, which were used to obtain information on demographics, medical history, family history of myocardial infarction (FHMI), ever smoking history, and alcohol use (#drinks/week). A medication inventory was also performed, and medications were grouped based on use to treat high blood pressure, elevated blood glucose or abnormal cholesterol. Standard measurements for height and weight were obtained, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight (kg) over height (cm2). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was measured 3 times in the seated position with a Dinamap model Pro 100 automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer after at least 5 minutes of rest. The average of the last 2 measurements was used. Blood samples were obtained after a 12 h fast for measurements of total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and glucose. Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, or use of hypoglycemic medications.

Statistical analysis

This is a period cross-sectional analysis of 1,413 participants with prevalent AAC measured from CT scans obtained between 2002 and 2005 and CVD risk factors measured at the baseline examination in MESA approximately 18 and 36 months previously. Descriptive statistics for the study cohort were presented across AAC density quartiles as means (SD) and medians (interquartile ranges, IQR) for normally distributed and skewed continuous variables (respectively), and frequencies for categorical variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the univariate associations of the AAC volume, and density scores. Backwards deleting multivariable linear regression (p < 0.10 for inclusion) was used to determine independent associations of CVD risk factors of age, sex, ethnicity, diabetes and ever smoking history, SBP, TC and HDL cholesterol, BMI, FHMI, use of alcohol, hypertension medications, and statin therapy with AAC volume and AAC density (separately). Models investigating correlates of AAC volume were additionally adjusted for AAC density, and vice versa. A multiplicative interaction term ethnicity X AAC volume (ethnicity*AAC volume) and ethnicity X AAC density (ethnicity*AAC density) was tested in models investigating correlates of AAC volume and density respectively. As AAC volume scores were skewed, natural log (ln) was used. All analyses were conducted using PSAW Statistics 20 (IBM, Corp., 2011 Amronk, NY).p-value ≤ 0.05 (two-sided) was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

Among the 1413 participants, the mean age was 65 ± 9 years, 52% were men, 44% were European-, 24% were Hispanic-, 18% were African-, and 14% were Chinese Americans (EA, HA, AA, and CA respectively). Median (IQR) for AAC volume, was 628 mm3 (157–1939 mm3), and mean AAC density was 3.0 ± 0.6 (Table 1). Compared to the lowest AAC density quartile, participants in the highest quartile had more AAC volume, were older, more likely to be male, less likely to be EA, and had a higher prevalence of statin use. Also, AAC density was correlated with ln(AAC volume) (correlation coefficient=0.65, p-value < 0.01) (not shown).

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics for participants with non-zero abdominal aortic calcium (AAC) scores by quartiles of AAC density.

| AAC density score, quartile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (0.88–2.75) N=354 |

Q2 (2.76–3.14) N=351 |

Q3 (3.15–3.46) N=355 |

Q4 (3.47–4.00) N=353 |

Cohort N= 1413 |

|

| AAC density, mean (SD) | 2.1 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.1) | 3.2 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.2) | 3.0 (0.6) |

| AAC volume, median (25–75th), mm3 | 92 (36–251) | 627 (266–1450) | 1259 (373–3202) | 1623 (600–3038) | 628 (157–1939) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 61 (8) | 65 (9) | 66 (9) | 67 (9) | 65 (9) |

| Men, N (%) | 186 (53%) | 197 (55%) | 172 (49%) | 175 (50%) | 730 (52%) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |||||

| European | 133 (38%) | 181 (51%) | 192 (54%) | 120 (34%) | 626 (44%) |

| Hispanic | 100 (29%) | 83 (23%) | 72 (21%) | 86 (24%) | 341 (24%) |

| African | 75 (21%) | 68 (19%) | 53 (15%) | 59 (16%) | 255 (18%) |

| Chinese | 42 (12%) | 26 (7%) | 35 (9%) | 88 (25%) | 191 (14%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Diabetes, N (%) | 41 (1 2%) | 50 (1 4%) | 42 (1 2%) | 44 (1 3%) | 177 (13%) |

| Ever smoker, N (%) | 184 (53%) | 197 (55%) | 206 (59%) | 192 (54%) | 779 (55%) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 29 (6) | 29 (5) | 28 (5) | 28 (5) | 28 (5) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | 127 (21) | 131 (22) | 131 (23) | 131 (21) | 130 (22) |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 195 (34) | 198 (34) | 198 (37) | 196 (35) | 197 (35) |

| HDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 50 (14) | 50 (13) | 50 (14) | 52 (15) | 50 (14) |

| Hypertension treatment, N (%) | 127 (36%) | 140 (39%) | 163 (46%) | 163 (46%) | 593 (42%) |

| Statin medication use, N (%) | 48 (14%) | 68 (19%) | 62 (18%) | 85 (24%) | 263 (19%) |

| Family history of myocardial infarction, N (%) | 127 (36%) | 178 (50%) | 163 (46%) | 137 (39%) | 605 (43%) |

| Alcohol use, median (25–75th), drinks/week | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–8) | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–7) |

HDL, high density lipoprotein.

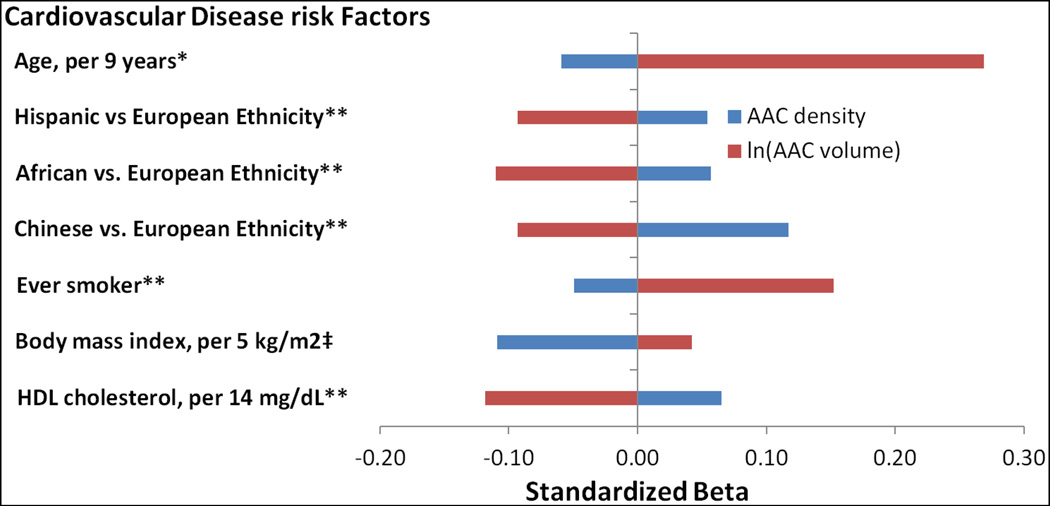

After adjustments for AAC density, compared to EA, each of HA, AA, and CA, had significantly lower ln(AAC volume) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). After similar adjustments, older age, ever smoking history, higher SBP, elevated TC, but reduced HDL cholesterol, FHMI, higher alcohol use, and Statin and antihypertensive medication use were significantly associated with higher ln(AAC volume). Finally higher BMI showed a borderline association (p=0.07) with higher ln(AAC volume). In contrast, after adjustments for ln(AAC volume), compared EA, each of HA, AA, and CA had significantly higher AAC density (Table 3 and Fig. 1). After similar adjustments, ever smoking history, higher BMI, and reduced serum HDL cholesterol were significantly associated with lower AAC density. Test for ethnicity*ln(AAC volume), and ethnicity*AAC density in models with AAC volume and AAC density as the outcome (respectively) was positive (p<0.01 for both).

Table 2.

Multivariable associations of ln(AAC volume) adjusted for AAC density in participants with non-zero AAC scores.

| Beta | 95% CI | Std. Betaa |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAC density | 1.50 | (1.39, 1.61) | 0.58 | <0.01* |

| Age, years | 0.05 | (0.04, 0.06) | 0.27 | <0.01* |

| Ethnicity (vs. European) | ||||

| Hispanic | −0.26 | (−0.43, −0.09) | −0. 07 | <0.0 1* |

| African | −0.47 | (−0.66, −0.28) | −0.11 | <0.01* |

| Chinese | −0.44 | (−0.66, −0.22) | −0.09 | <0.01* |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Ever smoker | 0.5 0 | (0.36, 0.64) | 0.1 5 | <0.0 1* |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.01 | (−0.001, 0.03) | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.01 | 0.002, 0.01) | 0.07 | <0.01* |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.004 | 0.002, 0.01) | 0.08 | <0.01* |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | −0.01 | (−0.02, −0.01) | −0.12 | <0.01* |

| Hypertension treatment | 0.16 | (0.01, 0.30) | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Statin medication use | 0.38 | (0.20, 0.55) | 0.09 | <0.01* |

| Family history of myocardial infarction | 0.22 | (0.08, 0.35) | 0.07 | <0.01* |

| Alcohol use, drinks/week | 0.01 | (0.003, 0.02) | 0.06 | <0.01* |

Standardized Beta, backwards deletion model with p-value < 0.1 for inclusion.

p-value (2-tailed) < 0.05 significant.

p-value for interaction term ethnicity X ln(AAC volume) <0.01.

Fig. 1. Differential associations of cardiovascular disease risk factors with abdominal aortic calcium (AAC) density and AAC volume separately.

Model for AAC density additionally adjusted for natural log (ln) AAC volume and vice versa. **Indicates significance (p-value < 0.05) in both models. *Indicates significance in ln(AAC volume) model only. ‡Indicates significance in AAC density model only.

Table 3.

Multivariable associations of abdominal aortic calcium (AAC) density adjusted for ln(AAC volume) in participants with non-zero AAC.

| Beta | 95% CI | Std. Betaa |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln(AAC volume) | 0.27 | (0.24, 0.29) | 0.71 | <0.01* |

| Age, years | −0.01 | (−0.01, 0) | −0.07 | <0.01* |

| Ethnicity (vs. European) | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.0 8 | (−0.01, 0.17) | 0.0 5 | 0.0 4* |

| African | 0.09 | (−0.02, 0.19) | 0.06 | 0.02* |

| Chinese | 0.22 | (0.14, 0.37) | 0.12 | <0.01* |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Ever smoker | −0. 06 | (−0.12, −0.003) | −0. 05 | 0.0 4* |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | −0.01 | (−0.02, −0.01) | −0.11 | <0.01* |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.003 | (0, 0.01) | 0.07 | <0.01* |

Standarized Beta, backwards deletion model with p-value < 0.1 for inclusion.

p-value (2-tailed) < 0.05 significant.

p-value for Interaction term ethnicity X AAC density < 0.01.

Discussion

In our study, compared to EA, each of HA, AA, and CA had lower AAC volume but higher AAC density. Also, older age, ever smoking history, reduced serum HDL cholesterol were independently associated with higher ln(AAC volume) but lower AAC density. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate correlates of calcified plaque composition (volume and density) separately.

While ethnic differences in the prevalence CAC have been reported, few studies have investigated AAC. In both a clinical and community cohort, CAC was more prevalent in EA, compared to other minority groups.10,11 In MESA, AAC was also more prevalent for EA.8 To date, most studies investigating calcified atherosclerotic plaques have used the Agatston method which up-weights for density, thus ethnic differences in calcium density in calcified plaques are unknown. In our study, compared to EA, each of HA, AA, and CA had less AAC volume but more AAC density, and CA had the strongest association with AAC density. Other MESA researchers have reported the lowest CVD event rates in CA, after adjustments for CVD risk factors.6

In our study, traditional atherosclerotic risk factors12 of older age, ever smoking history, higher BMI, and reduced HDL cholesterol, were positively associated with increased AAC volume, but lower AAC density. Furthermore, other known atherosclerotic risk factors such as; higher SBP and hypertension treatment, elevated total cholesterol and statin medication use, and FHMI were associated with higher AAC volume, but had no significant association with AAC density, and their associations tended to be inverse. Taken together, these results suggest that AAC density in contrast to AAC volume may not be independently associated with increased CVD risk, and further studies are needed to determine the impact of AAC density (in contrast to AAC volume) in CVD.

Supportive of our results are prior studies suggesting density of calcified plaque may be inversely associated with incident CVD. In two clinical cohorts of patients being evaluated for coronary artery disease by coronary CTA, the lowest CVD event rate was observed in participants with only calcified plaque, followed by those with mixed calcified and non-calcified plaques, while the highest rate was observed in those with non-calcified plaques.4,5 Furthermore, in MESA, after adjustments for CVD risk factors, higher CAC volume was associated increased CVD risk, while CAC density was protective.6 Studies of the differential association of AAC volume and density with CVD events are warranted.

The strengths of our study include a community-living, geographically and ethnically diverse cohort of both men and women who were free of clinically manifest CVD at recruitment. Our study, however, also has important limitations. First, the non-simultaneity of the predictor and outcome measures makes it problematic, even as a period cross-sectional study and we cannot assign temporality. However, it is unlikely that over a short period of time these measures would change systematically. Second, study sample was limited to participants with prevalent AAC, thereby limiting the generalizability of the results to individuals with calcified disease. Finally, AAC density was assessed using 4-point scale rather than a continuous HU scale (130 – 3000), thereby limiting power and the ability to detect significant associations.

Several CVD risk factors were associated with increased AAC volume, but lower AAC density. Further studies are needed to determine the impact of calcium density in the aorta and other vascular beds in CVD.

The standard method used to score calcified plaque in arteries, the Agatston, up-weights plaque for higher calcium density, thus modeling density as a CVD hazard. While the Agatston is widely used in CVD risk prediction models, the appropriateness of up-weighting for density is controversial. We observed that a greater burden of CVD risk factors was associated with higher AAC volume but lower AAC density. Our novel study supports prior research showing that increased calcium density in calcified plaque may be protective for CVD.

The composition of calcified plaque (calcium density content) which can be measured non-invasively may improve CVD risk stratification for the early implementation of CVD prevention strategies. Further studies are needed to better understand the impact of calcium density in CVD risk, and how best to incorporate calcium density in our CVD risk prediction models.

Highlights.

Older age was associated with higher abdominal aortic calcium (AAC) volume but lower AAC density

Compared to European ethnicity, minorities had lower AAC volume, but higher AAC density

A greater burden of cardiovascular (CVD) risk factors was associated with higher AAC volume but lower AAC density

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This study was supported by grant HL072403 and contracts N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants UL1-TR-000040 and UL1-TR-001079 from NCRR. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Abbreviations

- AA

African-Americans

- AAC

abdominal aortic calcium

- CA

Chinese-Americans

- CAC

Coronary artery calcium

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- EA

European-Americans

- HA

Hispanic-Americans.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared they do not have anything to disclose regarding conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, McClelland RL, et al. Abdominal aortic calcium, coronary artery calcium, and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1574–1579. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolland MJ, Wang TKM, van Pelt NC, et al. Abdominal aortic calcification on vertebral morphometry images predicts incident myocardial infarction. J Bone Miner Res Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:505–512. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.091005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson PW, Kauppila LI, O’Donnell CJ, et al. Abdominal aortic calcific deposits are an important predictor of vascular morbidity and mortality. Circulation. 2001;103:1529–1534. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou Z, Lu B, Gao Y, et al. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography and calcium score for major adverse cardiac events in outpatients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:990–999. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmadi N, Nabavi V, Hajsadeghi F, et al. Mortality incidence of patients with non-obstructive coronary artery disease diagnosed by computed tomography angiography. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Ix JH, et al. Calcium density of coronary artery plaque and risk of incident cardiovascular events. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:271–278. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Criqui MH, Kamineni A, Allison MA, et al. Risk factor differences for aortic versus coronary calcified atherosclerosis: the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2289–2296. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.208181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budoff MJ, Yang TP, Shavelle RM, et al. Ethnic differences in coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:408–412. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01748-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bild DE, Detrano R, Peterson D, et al. Ethnic differences in coronary calcification: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Circulation. 2005;111:1313–1320. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157730.94423.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]