Abstract

Transplantable murine models of ovarian high grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) that recreate key mutations seen in the human disease are greatly needed. These models would assist investigation of the relationship between tumour genotype, chemotherapy response and immune microenvironment. We performed whole exome sequencing of ID8, the most widely-used transplantable model of ovarian cancer, covering 194,000 exomes at a mean depth of 400x with 90% exons sequenced >50x. There were no functional mutations in genes characteristic of HGSC (Trp53, Brca1, Brca2, Nf1, Rb1), and p53 remained transcriptionally active. ID8 also demonstrated intact homologous recombination in functional assays. In addition, mutations typical of clear cell (Arid1A, Pik3ca), low grade serous (Braf), endometrioid (Ctnnb1) and mucinous (Kras) carcinomas were also absent. Using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, we generated novel ID8 derivatives with single (Trp53-/-) and double (Trp53-/-;Brca2-/-) deletions. In these CRISPR mutants, loss of p53 alone increases in vivo tumor growth rate within the peritoneal cavity of C57Bl/6 mice, and has significant effects upon immune microenvironment. Specifically, p53 loss increases CCL2 expression and induces immunosuppressive myeloid cell infiltration into tumour and ascites. Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- cells show significantly increased sensitivity to the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in vitro and slower intraperitoneal growth than Trp53-/-, with appearance of intra-tumoral tertiary lymphoid structures that are rich in CD3+ cells. These CRISPR-generated models represent a new and simple tool to investigate the biology of HGSC, and are freely available to researchers.

Keywords: ovarian high grade serous carcinoma, mouse model, ID8, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing

Introduction

Ovarian high grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) is the commonest subtype of human ovarian cancer (1) and long-term survival remains poor (2). Mutation in TP53 is essentially universal (3,4), whilst germline mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 is observed in approximately 15% cases (5,6). These mutations impair the ability to repair DNA double strand breaks (DSB) via homologous recombination (HR). The Cancer Genome Atlas consortium suggested that HR defects may be present in approximately 50% HGSC through a variety of additional mechanisms, including somatic BRCA1/2 mutation and epigenetic loss of BRCA1 expression (4). Another key development has been the finding that HGSC may arise in the fimbriae of the fallopian tube, rather than the ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) (7). Early STIC (serous tubal intra-epithelial carcinoma) lesions in the tubal fimbriae are observed in up to 10% of women with germline BRCA1/2 mutations undergoing prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy (8). Although a tubal origin of HGSC is widely accepted (9), STIC lesions are only seen in around half of HGSC cases (10). Recent data from mouse models (11,12) and clinical HGSC samples (13) suggest that the ovary itself may still be crucial in the pathogenesis of HGSC, and it is possible that there could be more than one origin of this tumor.

The absence of reliable murine models has been a major impediment in HGSC research (14). This is particularly important for investigation of the immune microenvironment. The presence of tumor infiltrating CD8 T lymphocytes (TILs) and tertiary intra-epithelial lymphoid aggregates are both associated with improved prognosis in HGSC (15,16), whilst intra-tumoral immunosuppressive myeloid and lymphoid cells (17,18) are associated with poor prognosis. However, it is unclear whether or how specific genomic events in HGSC influence the immune microenvironment.

The ID8 model, first described in 2000 (19), remains the only transplantable murine model of ovarian cancer routinely available. Whole ovaries from C57Bl/6 mice were trypsin-digested, and the dissociated cells passaged in vitro, initially in the presence of EGF. After approximately 20 passages, cells lost contact inhibition, and ten separate clones were derived, of which ID8 is the most widely used. Following intra-peritoneal injection of ID8 in syngeneic mice, diffuse peritoneal carcinomatosis, with blood-stained ascites, develops in approximately 110 days (19). Over 100 publications have utilized the ID8 model, but none has characterized it in light of current understanding of human ovarian cancer biology.

Here, we show that parental ID8 lacks mutations in Trp53, Brca1 and Brca2, and demonstrates HR competence in functional assays. We have used CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology to generate single (Trp53) and double (Trp53;Brca2) knockout derivatives of ID8 and evaluated their utility as a model of human HGSC. In particular, we show that loss of individual genes results in significant alterations in immune cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

ID8 cells, obtained from Dr Katherine Roby (University of Kansas Medical Center, KS), were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 4% fetal calf serum, 100µg/ml penicillin, 100µg/ml streptomycin and ITS (5 µg/ml insulin, 5µg/ml transferrin and 5ng/ml sodium selenite). As ID8 was obtained directly from their original source, separate STR validation was not performed. For cytotoxicity assays, cells were plated onto 24 plates (3x103 cells/well) in triplicate. Survival was assessed by MTT assay (Nutlin-3) or sulphorhodamine B assay (rucaparib) after 72 hours.

Next Generation Sequencing

Whole exome sequencing and analysis was performed by Beckman Coulter Genomics (Grenoble, France). Full details are given in Supplementary Methods. Summary results are presented in Supplementary tables 1 - 3. Primary sequencing data (BAM and VCF files) are available in the ArrayExpress database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MTAB-4663.

Sanger sequencing

Confirmatory Sanger sequencing of exons 2 – 9 of Trp53 was also performed on genomic DNA extracted from 107 parental ID8 cells in log-growth phase as well as from five separate ID8 microdissected tumors extracted from female C57Bl/6 mice after 110 days of intraperitoneal growth.

CRISPR/Cas9 and selection

Two open-access software programs, CHOPCHOP (https://chopchop.rc.fas.harvard.edu/) and CRISPR design (http://crispr.mit.edu/) were used to design guide RNAs (gRNA) targeted to Trp53 exon 5 and Brca2 exon 3. Three guides were designed per gene. Annealed oligonucleotides were ligated into BbsI-linearised pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro (PX459 (20), gifts from Feng Zhang via Addgene). Version 1 (Addgene # 48139) was employed for Trp53 deletion and version 2.0 (Addgene # 62988) for Brca2. All plasmids were sequenced to confirm successful ligation.

4x105 ID8 cells were plated overnight in antibiotic-free medium, and transfected with 4µg PX459 using Lipofectamine 2000, selected under puromycin (2.5 µg/ml) for 48 hours and plated onto 96 well plates (10 cells/ml). Single cell colonies were expanded for DNA extraction, protein extraction and cryopreservation.

PCR primers spanning potential sites of deletion were designed (Trp53: F 5’-cttccctcacattcctttcttg-3’; R 5’-gctgttaaagtagaccctgggc-3’, Brca2: F 5’-catggagggagtcacctttg-3’; R 5’-gctctggctgtctcgaactt-3’). Clones with large PCR deletions were selected for subsequent analysis. Remaining clones were screened using the Surveyor Nuclease Assay (Integrated DNA Technology). Mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. All sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT version 7 (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/)

Immunoblot and cytokine array

15μg of total protein was electrophoresed for at 140V for 1 hour, transferred onto nitrocellulose and blocked in 5% non-fat milk. Antibodies used were as follows: p53 (CM5, Novacastra and Ab26, Abcam), β actin (Sigma A1978). Membranes were exposed on a Chemi-doc MP (Biorad) with ECL (β actin) and ECL prime (p53). For array experiments, 5ml supernatant was collected from 106 cells plated for 16 hours on a 10cm plate, and centrifuged (2000 rpm for 5 min). Mouse Cytokine Antibody Array C1 (C-series) was blotted according to manufacturer’s instructions (RayBiotech, Inc. Norcross, GA).

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase PCR

RNA was extracted from 3x105 cells in log-growth phase, and 2µg was reverse transcribed (Applied Biosystems High Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit). 50ng cDNA was amplified using 10x iTaq qRT-PCR master mix (Biorad), 20X primer probe mix in a total of 20µl under the following cycle parameters: 2 minutes: 50°C, 10 minutes: 95°C, 40X (15 seconds: 95°C, 1 minute 60°C). All qRT-PCR primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems and Trp53 custom made from Sigma Aldrich: F 5’-catcacctcactgcatggac-3’, R 5’-cttcacttgggccttcaaaa-3’, probe 5’-ccccaggatgttgaggagt-3’. Values were normalised to Rpl-34.

γH2AX/Rad51 assay

Cells were seeded on coverslips and treated with rucaparib (10µM for 24 hours) or irradiated (10Gy), permeabilized with 0.2% Triton (Sigma) in PBS for 1min, then fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde and 2% sucrose for 10 min. Cells were stained with anti-γH2AX antibody (Millipore, Watford, UK) and co-stained with anti-Rad51 (Santa Cruz) antibody for 45 minutes at 37°C. Cells were co-stained with DAPI. Coverslips were mounted on slides and images captured using a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope and foci counted using ImageJ software. Cells were deemed HR competent if the number of Rad51 foci more than doubled in the presence of DNA double-strand break damage (≥2-fold increase in number of γH2AX foci) as previously described (21).

In vivo experiments

All experiments complied with the UK welfare guidelines (22) and were conducted under specific personal and project license authority. 5x106 cells were inoculated intraperitoneally (IP) in 6-8 week old female C57Bl/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories, UK). Mice were monitored regularly and killed upon reaching UK Home Office limits. All decisions about animal welfare and experiment endpoints were made by one of us (DA) independently of main study investigators to prevent bias. Ascites was collected and all visible tumor deposits dissected out. Half of tumor material was snap frozen (dry ice) and half fixed in neutral-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde. 5µm sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumors were stained (Dako Autostainer, Dako, UK) and quantified as detailed in Supplementary Methods.

Ascites preparation, tumor disaggregation and flow cytometry

Ascites was centrifuged (2200 rpm, 10 minutes) and supernatant stored at -80°C. The cell pellet was treated with red blood cell lysis buffer (Sigma Aldrich, UK – 5 minutes, room temperature), re-suspended in 10ml PBS, re-centrifuged, and stored at -80°C in FBS/10% DMSO. Solid tumor deposits in ice cold PBS/protease inhibitor solution were dissected into pieces less than 1mm diameter using a scalpel and digested at 37°C for 30 minutes (0.012% w/v collagenase type XI, 0.012% w/v dispase, 0.25% Trypsin in 0.1% BSA in RPMI.) 10ml of 0.1% BSA/RPMI was added and the tubes shaken vigorously followed by 100µm filtration. Cells were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1500 rpm, re-suspended in PBS containing 5% FBS, and then counted. Flow cytometry and gating strategies are presented in Supplementary Methods.

Results

Characterization of parental ID8 in vitro and in vivo

To assess the genomic landscape of ID8, we undertook whole exome sequencing, covering approximately 194,000 exons at a mean depth of 400x with 90% exons sequenced >50x. Approximately 6000 variants were identified, the vast majority of which were non-functional. Functional alterations (non-synonymous coding, stop-gain and frameshift) were identified in approximately 100 genes, the large majority of which were non-synonymous coding (See Supplementary Tables 1-3 for summary and list of all functional alterations). However, we were unable to identify any functional mutations in genes characteristic of HGSC (Trp53, Brca1, Brca2, Nf1, Rb1) and the absence of Trp53 mutations was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (data not shown). In addition, mutations typical of clear cell (Arid1A, Pik3ca), low grade serous (Braf), endometrioid (Ctnnb1) and mucinous (Kras) carcinomas were also notably absent. We did identify a mutation in Adamts3 (c.1089C>T; pV199I) – a recent analysis of TCGA data identified that mutations in ADAMTS genes were associated with platinum sensitivity as well as improved progression-free and overall survival in HGSC (23). In addition, mutation in Gabra6 (c.347T>G; pE22D) was identified. GABRA6 was one of the genes mutated at statistically significant frequency in TCGA analysis - however, transcription was absent in all TCGA tumors, suggesting that GABRA6 mutation is of minimal clinical relevance (4).

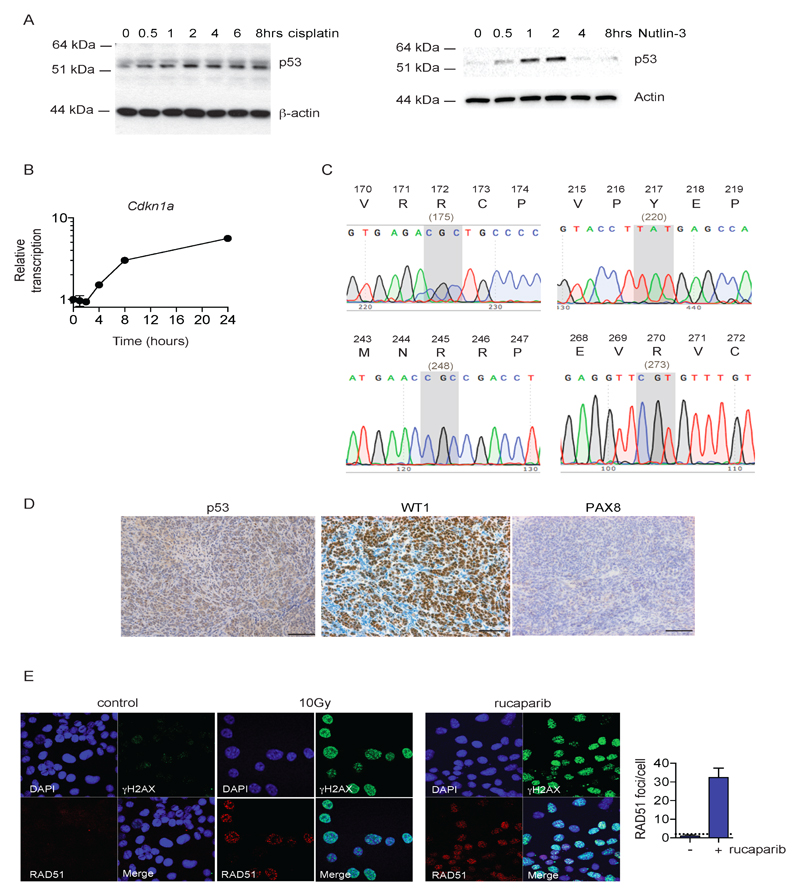

Given the centrality of TP53 mutations in HGSC, we also assessed p53 function in ID8. There was a robust increase in p53 protein following treatment with cisplatin and the MDM2 inhibitor Nutlin-3 (Fig. 1A), with marked increases in Cdkn1A (p21) transcription within 4 hours of cisplatin treatment (Fig. 1B), indicating that p53 remains transcriptionally active. Sanger sequencing of intraperitoneal ID8 tumors showed no Trp53 mutation in any tumor, including common hotspot mutations sites (R172, Y217, R245, R270 – Fig. 1C), whilst immunohistochemistry (IHC) confirmed a wild-type pattern of p53 expression (Fig. 1D). IHC examination of typical HGSC markers indicated that tumors were strongly and diffusely positive for WT1, but negative for Pax8 (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. ID8 retains wild-type p53 function and demonstrates competent homologous recombination.

A. Expression of p53 was assessed in ID8 cells following treatment for up to 8 hours with 10 µM cisplatin (left) or 10 µM Nutlin-3 (right)

B. Transcription of p53 target Cdkn1a in ID8 cells following treatment for up to 8 hours with 10 µM cisplatin was assessed by quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR, normalised to Rpl34. Data represent mean +/- s.d. (n=3) plotted relative to untreated cells (t = 0 hrs).

C. Representative chromatograms of Sanger sequencing of p53 from parental ID8 tumors harvested after 110 days intraperitoneal growth in female C57Bl/6 mice, demonstrating no mutations at critical hotspot mutations sites at residues 172, 217, 245 and 270 – the equivalent human codons are shown in parentheses below.

D. ID8 tumors, fixed in 4% neutral-buffered formalin, were stained for p53, WT1 and PAX8. Bars represent 100 µm.

E. ID8 cells were irradiated (10Gy) or treated with rucaparib (10µM for 24h), fixed and stained for γH2AX and RAD51, and counterstained with DAPI. RAD51 foci were counted in up to 30 untreated and rucaparib-treated cells. Bars represented mean (+/- s.d.) RAD51 foci per cell; dotted line represents two-fold increase in RAD51 foci/cell relative to untreated cells, suggestive of functional homologous recombination (21).

The whole exome sequencing data identified no functional abnormalities in Brca1, Brca2 or other HR genes. We confirmed that parental ID8 cells were able to form Rad51 foci in response to DNA double-strand break damage induced by irradiation as well as the PARP inhibitor rucaparib (Fig. 1E), and fulfilled the criteria of competent HR as previously described (21). Together, these data suggest that parental ID8 is poorly representative of human HGSC.

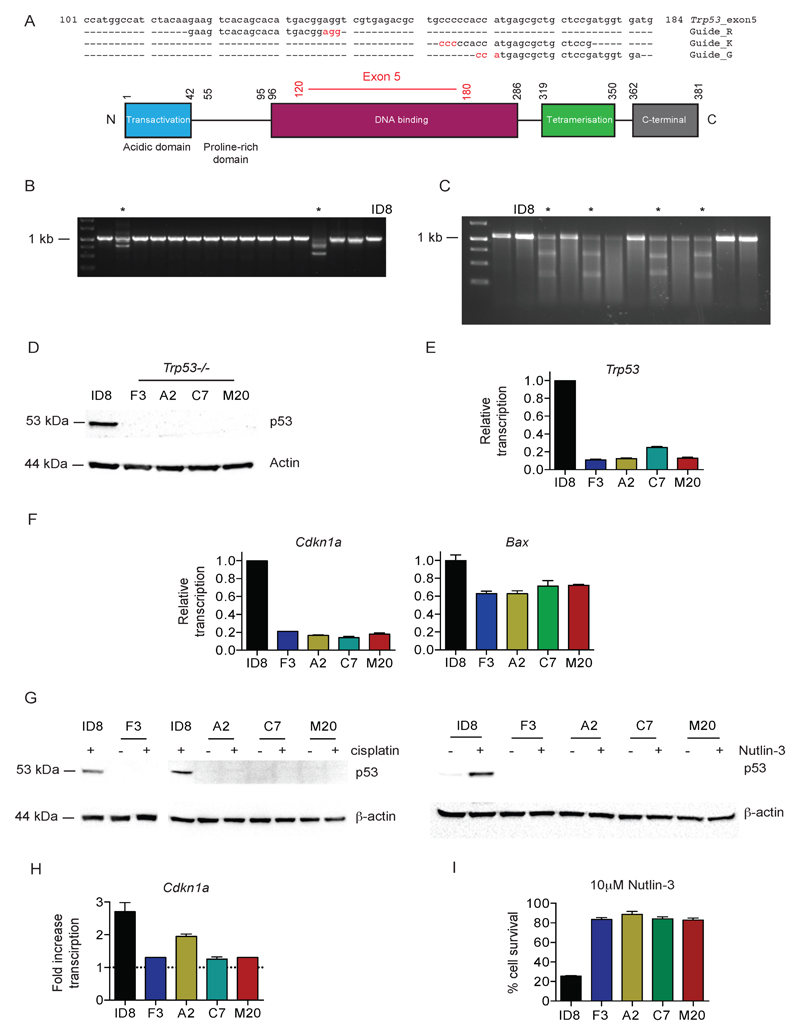

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Trp53 gene editing

Three separate guide RNA (gRNA) constructs targeted to exon 5 of Trp53 (Fig. 2A), were cloned into the PX450 plasmid. Following transfection and screening (Fig. 2B, C), clones were derived from all three guides (F3 – guide G; A2 – guide K; C7 and M20 – guide R), all of which contained bi-allelic deletions in Trp53 exon 5 (Fig. S1), ranging from 4bp (clone M20) to 280 bp (clone A2). All four null clones showed absent basal p53 expression by immunoblot (Fig. 2D), with significantly reduced basal transcription of Trp53 (Fig. 2E), Cdkn1a and Bax (Fig. 2F). There was also no increase in p53 expression following treatment with cisplatin or Nutlin-3 (Fig. 2G), nor an increase in Cdkn1a transcription following cisplatin (Fig. 2H). Finally, there was a significant reduction in cell death induced by Nutlin-3 in all four clones compared to parental ID8 (Fig. 2I). These results collectively indicate that all four Trp53-/- clones are functionally p53 deficient. We also isolated control clones that had been exposed to CRISPR plasmids (both empty PX459 and PX459 encoding Trp53 gRNA) but did not contain any Trp53 mutation on sequencing. These cells retained p53 transcriptional activity that was indistinguishable from parental ID8 (Fig. S2).

Figure 2. Generation and evaluation of Trp53-/- ID8 cells using CRISPR/Cas9.

A. Design of three gRNA sequences, targeted to exon 5 of Trp53 (upper). Nucleotides in red represent PAM sequences. Schematic representation of p53 protein (lower). Numbers represent amino acid positions. Amino acids encoded by exon 5 are marked in red.

B. Representative PCR of 1kb region spanning Trp53 exon 5 from genomic DNA extracted from ID8 and 15 single cell clones transfected with PX459 expressing gRNA K. Clones with demonstrable deletions are marked *.

C. Representative Surveyor Nuclease Assay, performed on ID8 and 11 single cell clones transfected with PX459 expressing Trp53 gRNA K as described in Material and Methods. Clones with mismatch suggestive of nucleotide deletion are marked *.

D. Expression of p53 was assessed in parental ID8 and four Trp53-/- clones by immunoblot

E. Transcription of Trp53 was assessed in parental ID8 and four Trp53-/- clones by quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR, normalised to Rpl34. Bars represent mean +/- s.d. (n=3) plotted relative to parental ID8.

F. Transcription of p53 target genes Cdkn1a and Bax was assessed in parental ID8 and Trp53-/- clones by quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR, normalised to Rpl34. Bars represent mean +/- s.d. (n=3) plotted relative to parental ID8.

G. Expression of p53 in ID8 and Trp53-/- clones before and after cisplatin (10 µM, 8 hours – left) and Nutlin-3 (10 µM, 2 hours – right).

H. Fold-increase in Cdkn1a transcription in ID8 and Trp53-/- clones following cisplatin treatment (10 µM, 8 hours). Bars represent mean +/- s.d. (n=3), and dotted line represents baseline transcription in each cell population.

I. ID8 and Trp53-/- clones were treated with 10 µM Nutlin-3, and cell survival assessed by MTT after 72 hours. Bars represent cell survival (mean +/- s.d., n=3) relative to untreated cells.

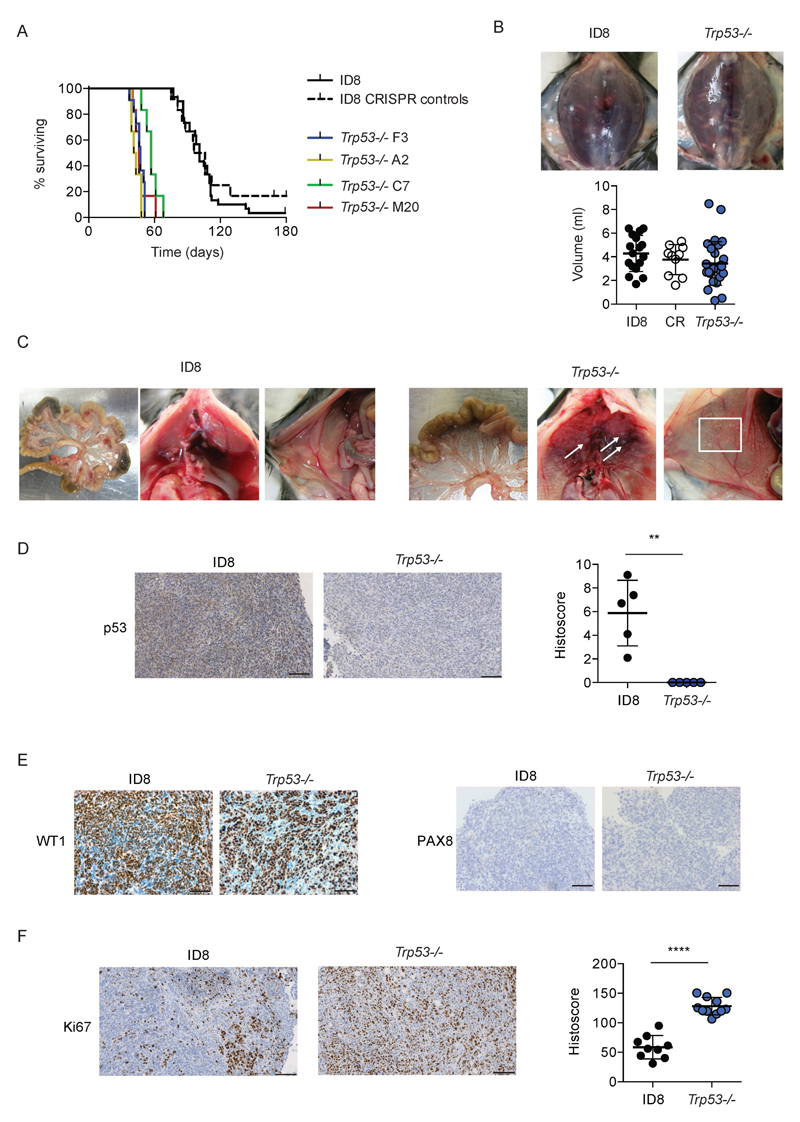

We then assessed intra-peritoneal growth of the Trp53-/- clones. Following intra-peritoneal injection into female C57Bl/6 mice, there was a highly significant reduction in time to reach predefined humane endpoints with all four clones. Median survival time ranged from 42-57 days (Fig. 3A), compared with 101 days for mice bearing either parental ID8 or CRISPR control cells (p<0.0001 for all clones compared to both parental ID8 and CRISPR controls). There was no difference in volume of ascites between parental ID8, CRISPR control or Trp53-/- tumors (Fig. 3B). Macroscopically, the patterns of growth and spread within the peritoneal cavity were similar, although there was some evidence of increased numbers of miliary deposits on the peritoneum and diaphragm in Trp53-/- tumors (Fig. 3C). By immunohistochemistry, we confirmed absence of p53 expression in Trp53-/- tumors (Fig. 3D). Trp53-/- tumors retained strong positivity for WT1, but remained negative for Pax8 (Fig. 3E). We also observed significant increases in Ki67 expression in Trp53-/- tumors (Fig. 3F), consistent with their more rapid intra-peritoneal growth.

Figure 3. Loss of p53 increases rate of intraperitoneal growth of ID8 tumors.

5x106 cells were injected intraperitoneally into female C57Bl/6 mice in groups of 6. Mice were killed when they reached humane endpoints. Ascites was taken from all mice and measured. Each point on histoscore plot represents mean score for multiple deposits (median 5, range 1 – 17) per animal normalised to tumor area.

A. Loss of p53 significantly increases rate of intraperitoneal growth (p<0.0001 for all Trp53-/- clones compared to both parental ID8 and CRISPR control cells). Data from four ID8 parental groups (total n=24) and two groups each of CRISPR control and Trp53-/- F3 (total n = 12) are plotted.

B. Loss of p53 does not alter volume of ascites at humane endpoint.

C. Loss of p53 increases number of tumor deposits on peritoneal (white box) and sub-diaphragmatic (arrows) surfaces. Representative images from at least mice per genotype.

D. Loss of p53 expression was confirmed by quantitative IHC in Trp53-/- tumors. **;p<0.01

E. No change in WT1 and PAX8 expression following p53 loss.

F. Loss of p53 expression significantly increases intraperitoneal tumor proliferation, as measured by Ki67 staining. ****;p<0.0001.

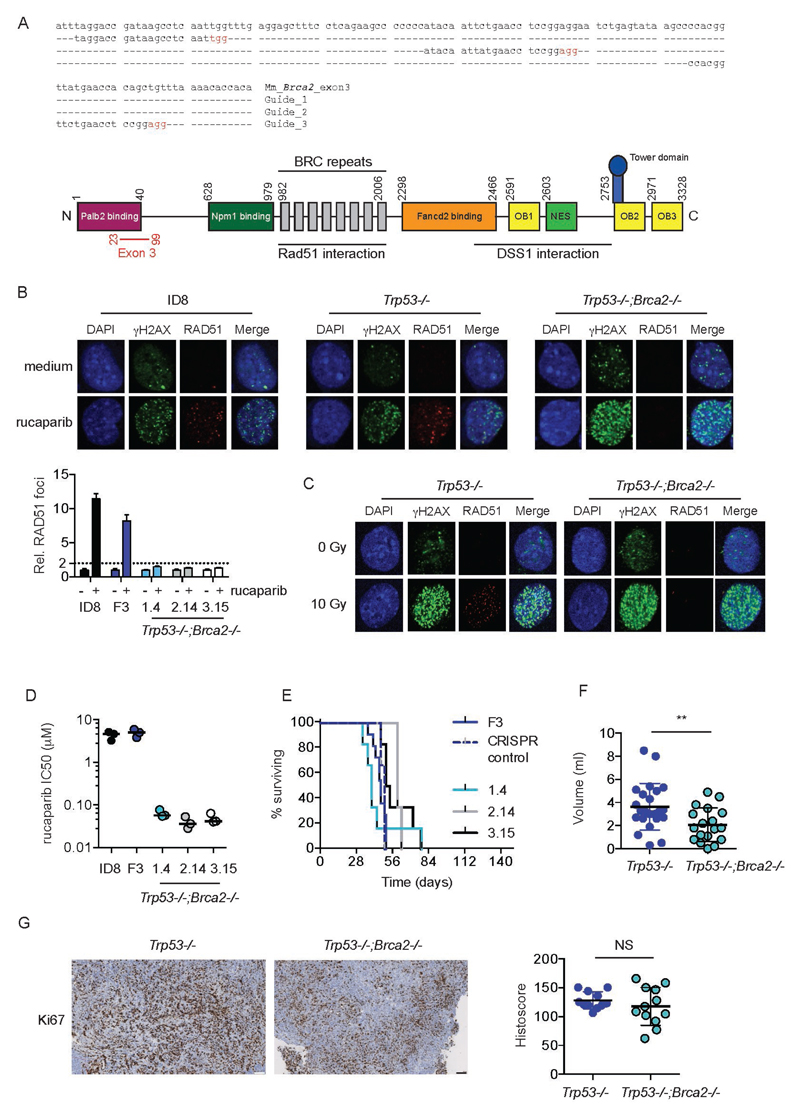

Generation of double Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- mutants

We next targeted exon 3 of Brca2, which encodes the PALB2 binding domain (Fig. 4A). Using the F3 Trp53-/- clone, we generated three separate double Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- clones (1.4, 2.14 and 3.15), each derived from a different guide, and each with distinct deletions (Fig. S3). All three Trp53-/- ;Brca2-/- clones fulfilled the criteria for defective HR (21) (Fig. 4B) and lost the ability to form Rad51 foci in response to irradiation (Fig. 4C, Fig. S4). In addition, all clones were significantly more sensitive to PARP inhibitor-mediated cytotoxicity (Fig. 4D). By contrast, control cells (Trp53-/- cells exposed to PX459 encoding Brca2 gRNA but with no Brca2 deletion) had the same sensitivity to rucaparib as parental ID8 and F3 Trp53-/-, and were HR competent by Rad51 assay (data not shown).

Figure 4. Generation and evaluation of Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- ID8 cells using CRISPR/Cas9.

A. Design of three gRNA sequences, targeted to exon 3 of Brca2 (upper). Nucleotides in red represent PAM sequences. Schematic representation of Brca2 protein (lower). Numbers represent amino acid positions. OB – oligonucleotide binding domain; NES – nuclear export signal. Amino acids encoded by exon 3 are marked in red.

B. Parental ID8, Trp53-/- cell line F3 and three Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- cells were treated with rucaparib (10µM), fixed and stained for γH2AX and RAD51, and counterstained with DAPI. Representative confocal microscopy images are presented (upper panels). RAD51 foci were counted in up to 30 untreated and rucaparib-treated cells. Bars represented mean (+/- s.d.) foci per cell relative to untreated cell; dotted line represents two-fold increase in foci/cell relative to untreated cells.

C. Trp53-/- cell line F3 andTrp53-/-;Brca2-/- 3.15 cells were irradiated (10Gy), fixed and stained for γH2AX and RAD51, and counterstained with DAPI.

D. Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- cells are significantly more sensitive to PARP inhibitor-induced cytotoxicity than either parental ID8 or Trp53-/- cell line F3. Each dot represents IC50 value from a single experiment performed in triplicate. Bars represent median IC50 for three separate experiments.

E. 5x106 cells were injected intraperitoneally into female C57Bl/6 mice in groups of 6. Mice were killed when they reached humane endpoints. Ascites was taken from all mice and measured. F3 CRISPR control cells are Trp53-/- F3 cells exposed to PX459 encoding Brca2 gRNA (Guide 1), but which contain no deletion in Brca2 on sequencing.

F. Loss of Brca2 and p53 reduces volume of ascites compared to loss of p53 alone. **;p<0.01.

G. Additional loss of Brca2 expression does not significantly alter intraperitoneal tumor proliferation, as measured by Ki67 staining. Bars on IHC images represent 100 µm. Each dot represents mean histoscore for multiple deposits (median 5, range 1 – 17) per animal, normalised to tumor area.

We also assessed intraperitoneal growth of Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- clones. When analyzed individually, there was no difference in mouse survival between Trp53-/- F3 tumors and any of the double null tumors (Fig. 4E). However, when analyzed collectively, there was a small, but significant, increase in survival: mice bearing Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- tumors survived 10 days longer than Trp53-/- F3 tumors (57 vs 47 days; p<0.01. Fig. S5). In addition, mice had significantly lower ascites volumes than either parental or Trp53-/- tumors (Fig. 4F). There were large diaphragmatic and peritoneal deposits, and ascites was consistently less hemorrhagic (Fig. S6). Ki67 histoscores were significantly higher than ID8 parental tumors (not shown) but not significantly different to those seen in Trp53-/- (Fig. 4G).

Tumor microenvironment

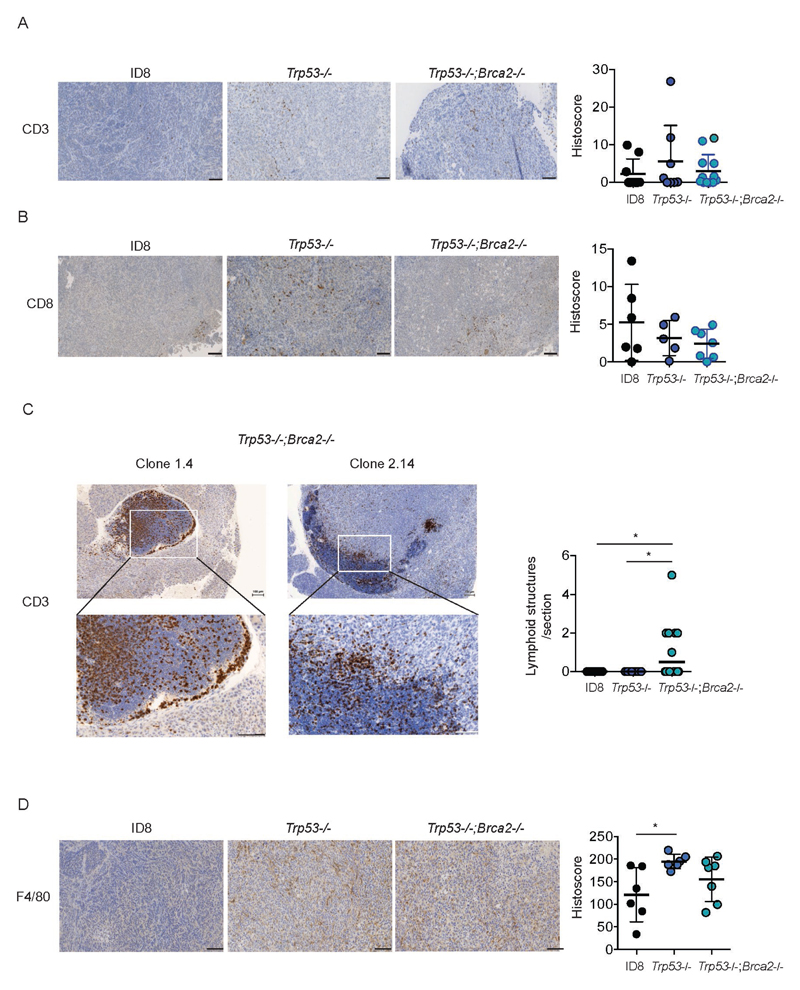

To investigate the utility of our new ID8 derivatives to study the relationship between specific mutations within malignant cells and the tumor microenvironment, we first stained tumors for the presence of T lymphocytes (both CD3 and CD8) and macrophages (F4/80). Intra-epithelial CD3+ and CD8+ cells were both generally sparse, with no significant differences between any of the tumor genotypes (Fig. 5A, 5B). However, we observed the presence of lymphoid aggregates within Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- tumors that were absent from both parental ID8 and Trp53-/- tumors (Fig. 5C, Fig. S7, 8). These aggregates were composed predominantly of CD3+ cells, although CD8+ populations were visible at the periphery (Fig. S9). We also observed striking and significant increases in macrophage infiltration in Trp53-/- tumors (Fig. 5D, Fig. S10). Macrophage infiltration was more variable in Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- tumors – median histoscore was greater than in ID8 parental tumors but lower than in Trp53-/- tumors, although neither difference was statistically significant (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. Loss of p53 and Brca2 expression alters immune cell infiltration in ID8 tumors.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumors from all three genotypes (parental ID8, Trp53-/- and Trp53-/-;Brca2-/-) were stained for CD3 (A) and CD8 (B). The number of intra-epithelial lymphoid aggregates, defined as an area >0.1mm2, was counted in tumors from all three genotypes (C). No aggregates were identified in ID8 and Trp53-/- tumors. Bar represents median. *:p<0.05. Tumors were also stained for F4/80 (D). All bars represent 100 µm. Intensity of expression was quantified as detailed in Materials and Methods. Each dot represents mean histoscore for multiple deposits per animal, normalised to tumor area. *;p<0.05.

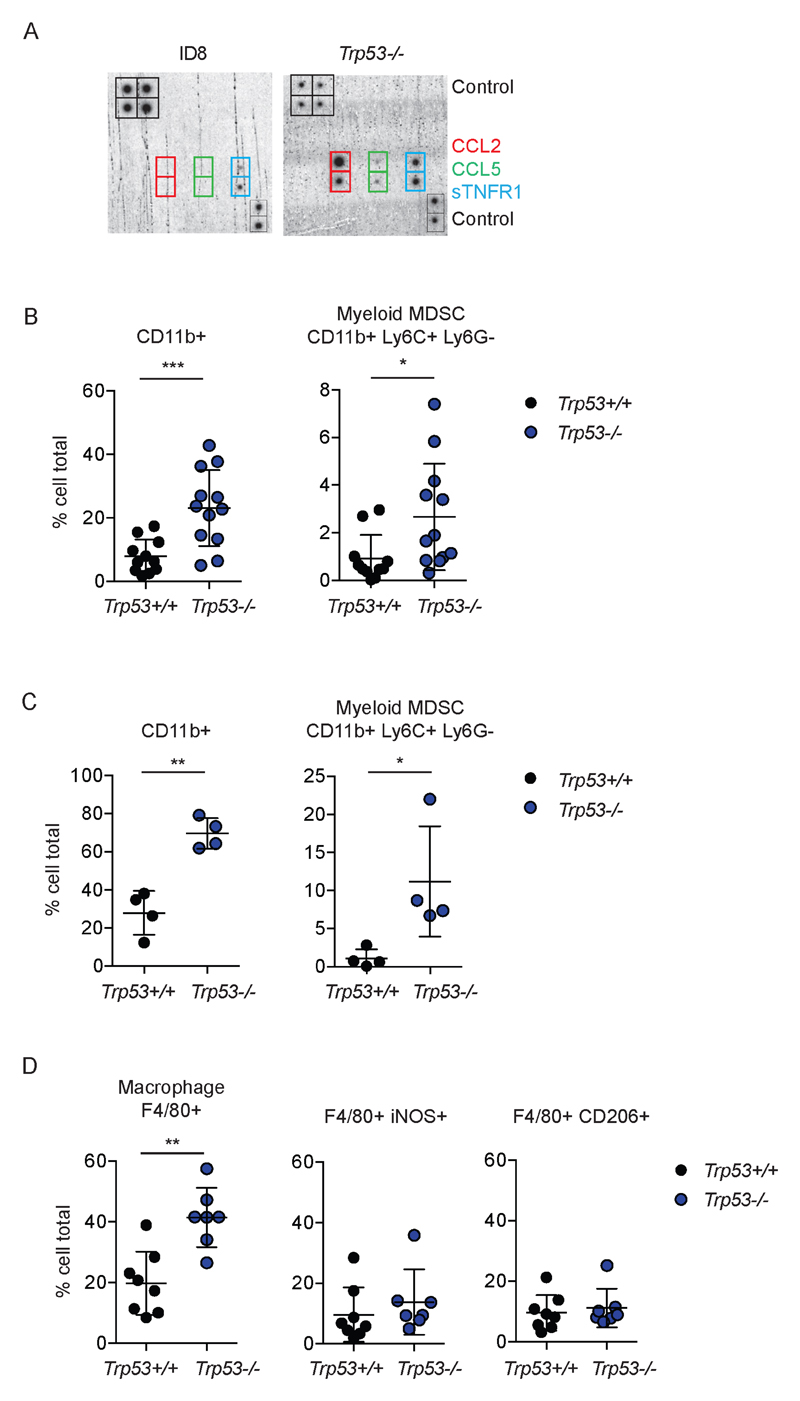

We next investigated the specific role of p53 loss upon myeloid populations. Immunoblot array showed marked increases in the monocyte chemoattractant CCL2, and, to a lesser extent, CCL5 and sTNFR1 in conditioned medium from Trp53-/- cells (Fig. 6A, Fig. S11). Immunophenotyping of disaggregated solid tumor deposits (Fig. 6B, Fig. S12) and ascites (Fig. 6C, Fig. S12) showed significant increases in CD11b+ populations in Trp53-/- tumors compared to Trp53 wild-type. Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (defined as CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G-) were the predominant myeloid population in both tumor and ascites compared to polymorphonuclear (PMN) MDSC populations (CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G+). Consistent with IHC, we found significantly more F4/80 positive cells within Trp53-/- ascites, although the proportions of iNOS+ and CD206+ cells did not alter significantly between the two genotypes (Fig. 6D, Fig. S13).

Figure 6. Loss of p53 expression increases CCL2 expression and induces immunosuppressive myeloid cell infiltration in tumor and ascites.

A. Expression of chemokines in conditioned medium was assessed using immunoblot array. See Fig. S9 for complete array layout.

B, C and D. Disaggregated whole tumor deposits (B) and ascites cells (C, D) were assessed by flow cytometry for CD4, CD8, CD11b, Ly6G, Ly6C, F4/80, CD206 and iNOS. Each dot represents a single tumor deposit (minimum three deposits/mouse) or ascites sample. Bars represent mean +/- s.d. Trp53+/+ populations include ID8 parental and CRISPR control cells lacking any Trp53 mutation. ***;p<0.001, **;p<0.01, *;p<0.05.

Discussion

Here we show that ID8, a widely used murine model of ovarian carcinoma, is poorly representative of HGSC, with a conspicuous absence of mutations in genes associated with the human disease, and evidence of functional p53 activity. The overall mutational burden in ID8 is low (functional variants in only 100 genes in 49MB of sequenced DNA), which concurs with very recent data from ID8-G7, a subline of ID8 that has been passaged in vivo (24). We did not observe activating mutations in common oncogenes (e.g. Kras, Nras, Myc, Egfr, Pik3ca) that may drive carcinogenesis in parental ID8 cells, but we have not undertaken copy number analyses, and thus cannot exclude the presence of an oncogenic amplification.

Using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, we generated sublines of ID8 bearing loss-of-function deletions in Trp53 and Brca2, and demonstrate that these alter tumor growth in the peritoneal cavity. In preliminary experiments, we also show that single gene mutations can alter the tumor microenvironment, with a significant increase in immunosuppressive myeloid populations within tumor and ascites upon loss of p53 expression, as well as the appearance of intra-epithelial lymphoid aggregates in tumors lacking both p53 and Brca2.

Genetically engineered mouse models of HGSC have been difficult to generate (25). Recently, two HGSC models were described: the Drapkin lab utilized the Pax8 promoter to drive Cre-mediated recombination of Trp53 and Pten with Brca1 or Brca2 in mouse fallopian tube secretory epithelium. This resulted in development of STIC lesions, and subsequent invasive tumors in the ovary and peritoneal cavity within 20 weeks (26). By morphology and immunohistochemistry, the tumors resembled human HGSC, but no ascites was observed and all Pten-/- mice developed endometrial lesions (hyperplasia, dysplasia or carcinoma). In addition, no transplantable cell lines have been described from these mice. A second fallopian tube model has been described, with SV40 large T-antigen under the control of the Ovgp-1 promoter (27,28). Again, STIC-like lesions with p53 signatures were described, as well as invasive tumors within the ovary. However, no peritoneal dissemination or ascites were seen, and, again, no lines that can be readily transplanted into non-transgenic mice have been described. Both of these models are undoubtedly of great importance. However, we believe that a transplantable model, based on a single genetic background (C57Bl/6), which recapitulates disseminated peritoneal disease with ascites and in which multiple genotypes can potentially be rapidly investigated in parallel, is an important adjunct to transgenic models.

One potential criticism of our models is that they arise from a single cell line. Although other murine ovarian cancer cell lines have been described (29), they derive from chimeric SV40 T-Ag animals, and thus cannot be transplanted into non-transgenic animals, which significantly reduces their utility. ID8 remains the only murine line derived from a single non-transgenic strain from which to base these models. A second potential criticism is the cell of origin of ID8 itself. In the original description of ID8 (19), whole mouse ovaries were trypsinized with the aim of removing the OSE layer, but the exact cell of origin of ID8 is unclear. Although the fallopian tube is undoubtedly the originating site of many HGSC, a potential ovarian origin is possible for a subset of these tumors (13). In addition, data from the Drapkin lab model indicated that oophorectomy reduced peritoneal dissemination, suggesting that the ovary plays a role in promoting metastatic spread of fallopian tube lesions (26). Thus, an OSE origin of ID8 does not preclude the applicability of our new cells as a model of HGSC, and our tumors do express some typical HGSC markers (e.g. WT1). However, the absence of Pax8 staining strongly suggests that ID8 is not of fallopian tube secretory origin. PAX8 staining is used in the diagnosis of HGSC and is usually strongly positive, although this is not universal (30). Therefore, the absence of Pax8 in our ID8 models is important to note, but is not a barrier to their use in HGSC research.

Although CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing is an extremely powerful tool, off-target effects can occur (31,32), which are difficult to quantify precisely in any given model without whole genome sequencing. Here, we used multiple different guides and selected at least one clone per guide. In addition, we utilized appropriate negative controls (cells exposed to CRISPR plasmid transfection but which do not contain mutations in target gene). The uniform phenotypes observed in each of our models suggest strongly that any off-target effects are not significant.

Finally, we have undertaken preliminary experiments to investigate the link between tumor-specific mutations and immune composition in the microenvironment. Here, we show that loss of p53 increases CCL2 expression and induces marked increases in immunosuppressive myeloid populations both within solid tumor deposits and ascites. CCL2 is a critical chemokine for attraction of monocyte populations; wild-type p53 can suppress CCL2 expression via direct binding to the CCL2 5’UTR (33) and can reduce CCL2-induced xenograft growth (34). In Trp53-/- tumors, there appeared to be a bias towards monocyte MDSC populations, which have been characterized as more immunosuppressive than PMN MDSC in tumor-bearing mice (35). Intriguingly, we also observed aggregates of lymphoid cells in tumors lacking both p53 and Brca2. The structures contained hundreds of cells, which were predominantly CD3+ but CD8-. Four different types of lymphoid aggregates in HGSC were recently described, the largest of which resembled activated lymph nodes (16), and which contain a variety of T and B cell lineages, including plasma cells. The presence of plasma cells was associated with expression of two genes, IGJ and TNFRSF17, but was independent of mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Our preliminary data suggest that loss of Brca2 and p53 can lead to formation of tertiary lymphoid aggregates, but further work, including gene expression analysis and further flow cytometry, will be required to elucidate this relationship. It is not clear whether these microenvironmental changes explain why loss of Brca2 and p53 function results in slower intraperitoneal growth compared to p53 loss alone. Ki67 staining suggests that there is no significant reduction in proliferation in the Trp53-/-;Brca2-/- tumors, suggesting that non-cell autonomous factors may be contributing. Certainly, in patients with HGSC, BRCA2 mutation and the presence of intra-tumoral lymphocytes (15) are both associated with longer overall survival (36), although the precise mechanisms for this remain unclear.

In summary, we have used gene editing technology to generate transplantable murine ovarian cancer cell lines that recapitulate critical mutations in human HGSC. Our results suggest that our ID8 models may act as an important tool, alongside GEMM and primary patient material, in understanding the complexities of HGSC biology. Further mutants are under construction, and all our ID8 derivatives are freely available to other researchers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the University of Glasgow (IAMcN) and Cancer Research UK (grants C16420/A12995 [IAMcN], C596/A18076 [KV], C608/A15973 [IAMcN], C596/A20921 [KV] and C16420/A16354 [FRB]). All animal work was performed in the Biological Services Unit facilities at the Cancer Research UK Beatson Institute (Cancer Research UK grant C596/A17196). We would like to thank Emma Johnson for expert technical assistance with mouse experiments and Colin Nixon and Marion Stevenson for immunohistochemistry.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 1.Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J, Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, Kristensen G, et al. A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2484–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowtell DD, Bohm S, Ahmed AA, Aspuria PJ, Bast RC, Jr, Beral V, et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer II: reducing mortality from high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(11):668–79. doi: 10.1038/nrc4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed AA, Etemadmoghadam D, Temple J, Lynch AG, Riad M, Sharma R, et al. Driver mutations in TP53 are ubiquitous in high grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. J Pathol. 2010;221(1):49–56. doi: 10.1002/path.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.TCGA. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang S, Royer R, Li S, McLaughlin JR, Rosen B, Risch HA, et al. Frequencies of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among 1,342 unselected patients with invasive ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(2):353–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, Defazio A, Emmanuel C, George J, et al. BRCA Mutation Frequency and Patterns of Treatment Response in BRCA Mutation-Positive Women With Ovarian Cancer: A Report From the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2654–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R, Nucci MR, Medeiros F, Saleemuddin A, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J Pathol. 2007;211(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/path.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y, Elvin JA, Callahan MJ, Feltmate C, et al. The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2006;30(2):230–6. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000180854.28831.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh N, Gilks CB, Hirschowitz L, Kehoe S, McNeish IA, Miller D, et al. Primary site assignment in tubo-ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma: Consensus statement on unifying practice worldwide. Gynecologic Oncology. 2016;141(2):195–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, Hirsch MS, Feltmate C, Medeiros F, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2007;31(2):161–9. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213335.40358.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flesken-Nikitin A, Hwang CI, Cheng CY, Michurina TV, Enikolopov G, Nikitin AY. Ovarian surface epithelium at the junction area contains a cancer-prone stem cell niche. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature11979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J, Coffey DM, Ma L, Matzuk MM. The ovary is an alternative site of origin for high-grade serous ovarian cancer in mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156(6):1975–81. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howitt BE, Hanamornroongruang S, Lin DI, Conner JE, Schulte S, Horowitz N, et al. Evidence for a dualistic model of high-grade serous carcinoma: BRCA mutation status, histology, and tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015;39(3):287–93. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaughan S, Coward JI, Bast RC, Jr., Berchuck A, Berek JS, Brenton JD, et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer: recommendations for improving outcomes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(10):719–25. doi: 10.1038/nrc3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, Gimotty PA, Massobrio M, Regnani G, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(3):203–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroeger DR, Milne K, Nelson BH. Tumor infiltrating plasma cells are associated with tertiary lymphoid structures, cytolytic T cell responses, and superior prognosis in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10(9):942–49. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kryczek I, Wei S, Zhu G, Myers L, Mottram P, Cheng P, et al. Relationship between B7-H4, regulatory T cells, and patient outcome in human ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67(18):8900–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roby KF, Taylor CC, Sweetwood JP, Cheng Y, Pace JL, Tawfik O, et al. Development of a syngeneic mouse model for events related to ovarian cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(4):585–91. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nature protocols. 2013;8(11):2281–308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukhopadhyay A, Elattar A, Cerbinskaite A, Wilkinson SJ, Drew Y, Kyle S, et al. Development of a functional assay for homologous recombination status in primary cultures of epithelial ovarian tumor and correlation with sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(8):2344–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Workman P, Aboagye EO, Balkwill F, Balmain A, Bruder G, Chaplin DJ, et al. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(11):1555–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Yasukawa M, Chen K, et al. Association of somatic mutations of adamts genes with chemotherapy sensitivity and survival in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncology. 2015;1(4):486–94. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin SD, Brown SD, Wick DA, Nielsen JS, Kroeger DR, Twumasi-Boateng K, et al. Low Mutation Burden in Ovarian Cancer May Limit the Utility of Neoantigen-Targeted Vaccines. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark-Knowles KV, Senterman MK, Collins O, Vanderhyden BC. Conditional inactivation of Brca1, p53 and Rb in mouse ovaries results in the development of leiomyosarcomas. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(12):e8534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perets R, Wyant GA, Muto KW, Bijron JG, Poole BB, Chin KT, et al. Transformation of the fallopian tube secretory epithelium leads to high-grade serous ovarian cancer in brca;tp53;pten models. Cancer Cell. 2013;24(6):751–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyoshi I, Takahashi K, Kon Y, Okamura T, Mototani Y, Araki Y, et al. Mouse transgenic for murine oviduct-specific glycoprotein promoter-driven simian virus 40 large T-antigen: tumor formation and its hormonal regulation. Molecular reproduction and development. 2002;63(2):168–76. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherman-Baust CA, Kuhn E, Valle BL, Shih Ie M, Kurman RJ, Wang TL, et al. A genetically engineered ovarian cancer mouse model based on fallopian tube transformation mimics human high-grade serous carcinoma development. J Pathol. 2014;233(3):228–37. doi: 10.1002/path.4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connolly DC, Bao R, Nikitin AY, Stephens KC, Poole TW, Hua X, et al. Female mice chimeric for expression of the Simian Virus 40 TAg under control of the MISIIR promoter develop epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63(6):1389–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Köbel M, Kalloger SE, Boyd N, McKinney S, Mehl E, Palmer C, et al. Ovarian Carcinoma Subtypes Are Different Diseases: Implications for Biomarker Studies. PLoS medicine. 2008;5(12):e232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai SQ, Zheng Z, Nguyen NT, Liebers M, Topkar VV, Thapar V, et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nature biotechnology. 2015;33(2):187–97. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim D, Bae S, Park J, Kim E, Kim S, Yu HR, et al. Digenome-seq: genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nature methods. 2015;12(3):237–43. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3284. 1 p following 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang X, Asano M, O'Reilly A, Farquhar A, Yang Y, Amar S. p53 is an important regulator of CCL2 gene expression. Current molecular medicine. 2012;12(8):929–43. doi: 10.2174/156652412802480844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang X, Amar S. p53 suppresses CCL2-induced subcutaneous tumor xenograft. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2015;36(4):2801–8. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2906-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A, et al. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111(8):4233–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Candido Dos Reis FJ, Song H, Goode EL, Cunningham JM, Fridley BL, Larson MC, et al. Germline mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 and ten-year survival for women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(3):652–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.