Abstract

Schizophrenia patients have an increased risk of cardiac dysfunction. A possible factor underlying this comorbidity are the common variants in the large set of genes that have recently been discovered in genome-wide association studies (GWASs) as risk genes of schizophrenia. Many of these genes control the cell electrogenesis and calcium homeostasis. We applied biophysically detailed models of layer V pyramidal cells and sinoatrial node cells to study the contribution of schizophrenia-associated genes on cellular excitability. By including data from functional genomics literature to simulate the effects of common variants of these genes, we showed that variants of voltage-gated Na+ channel or hyperpolarization-activated cation channel-encoding genes cause qualitatively similar effects on layer V pyramidal cell and sinoatrial node cell excitability. By contrast, variants of Ca2+ channel or transporter-encoding genes mostly have opposite effects on cellular excitability in the two cell types. We also show that the variants may crucially affect the propagation of the cardiac action potential in the sinus node. These results may help explain some of the cardiac comorbidity in schizophrenia, and may facilitate generation of effective antipsychotic medications without cardiac side-effects such as arrhythmia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a heritable mental disorder with a high burden of morbidity and large social impacts1. A recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) has identified more than a hundred genetic loci exceeding genome-wide significance2. The loci implicate genes that encode numerous ion channel subtypes and calcium transporters and are major contributors to the functions of cells in not only brain but also organs outside the central nervous system, such as heart. Evidence for increased cardiac dysfunction in SCZ patients are shown by meta-studies that reported a 2.5–3-fold increase in mortality rates3,4. Approximately 40% of the excess deaths are caused by accidents and suicides, while the remaining 60% are natural5—and largely due to cardiovascular disease6. Some of these excess deaths are linked to the increased risk of sudden cardiac death conveyed by long-term use of antipsychotic drugs7, many of which are known to have side-effects related to arrhythmia, including prolongation of QT interval8 and torsades de pointes9. In parallel to these observations, GWASs of cardiac phenotypes, such as electrocardiographic (ECG) measures, highlight a set of genes that overlaps with the one discovered in GWASs of SCZ10,11. Nevertheless, both the genetic and mechanistic connections between cardiac and neural phenotypes in SCZ patients remain poorly understood. Here, we attempt to combine our recently developed genetic approaches with biophysical models of well-characterized cardiac and neuronal cell types to provide general mechanistic links between neural and cardiac tissue for SCZ-associated variants.

It is of key relevance to know if there is an inherent, genetic risk in addition to the external, drug-induced risks in the treatment of SCZ that may underlie the comorbidity between cardiac disease and SCZ—the SCZ-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) might, however, as well be protective against cardiac disease. The effects of primarily brain disorder-related SNPs on cardiac phenotypes is a largely unexplored area, while there are a few examples of the opposite: SNPs that were first identified by a cardiac disease and then found to convey a risk of brain dysfunction, such as seizures12,13. The cellular homogeneity in the heart, in contrast to the heterogeneity in both structure and function of the brain, is an important aid in uncovering cross-tissue functional genetics in both approaches.

SCZ is associated with genes affecting transmembrane currents of all major cationic species, Na+, K+, and Ca2+ (ref. 2). In addition, some of the SCZ-linked genes are involved in regulation of intracellular Ca2+ dynamics2, which importantly modulate cellular excitability in both the heart and brain, via a range of Ca2+-sensitive plasma membrane current carriers. The rise of biophysical modeling of neurons14 and cardiac pacemaker cells15 provide a solid basis for analyzing this intrinsic excitability as a coordinated interplay of ion channels and ion transporters. In addition, there is an increasing amount of in vitro data on the effect of genetic variations on such ion channel or calcium transporter functions, and much of these data can be implemented in the biophysical models. This opens the door for a mechanistic analysis of SCZ-related genes16, mapping the functional genomics data to predictions of cellular function and dysfunction both in neural and cardiac tissue.

In this work, we use computational modeling to study the contribution of SCZ-associated genes to cardiac and neuronal excitability. We focus our analyses on two well-studied cell types that are central to cortical information processing and cardiac pacemaking, namely, layer V pyramidal cells (L5PCs) in the cortex and sinoatrial node cells (SANCs) in the myocardium. The apical tuft of an L5PC integrates non-local synaptic inputs, and is considered a biological substrate for cortical associations providing high-level context for low-level (e.g., sensory) inputs that arrive at the perisomatic compartments17. Therefore, the ability of L5PC to integrate the apical and perisomatic inputs has been proposed as one of the mechanisms that could be impaired in hallucinating patients17. The SANCs, in turn, have a key role in controlling heart rate as the primary pacemakers of the mammalian heart. While SANCs derive from cardiac lineage and are, therefore, regarded as a specialized form of myocardium, their morphology, electrophysiology, and ion-channel expression profiles are the most neuron-like of any studied cardiac muscle cell type. As such, they represent a population of cardiac cells that may be most apt to display functional alterations as a result of SCZ-associated variants. We apply two recent L5PC models18,19 and two recent SANC models20,21 to argue for the generality of our findings.

We show that subtle SNP-like variants of ion-channel and calcium-transporter-encoding genes cause notable effects in intrinsic excitability of both neurons and heart cells. Our approach is limited by the data concerning the functional effects of the SCZ-related common genetic variants. To overcome this limitation, we concentrate on a set of in vitro-observed effects of more extreme genetic variations, as described previously16. A key assumption of our approach is that the effects of SNP variants can be represented as downscaled versions of the more extreme variants, and that the emergence of disease phenotypes results from the combined effect of a large number of subtle SNP effects22,23. Our results contribute to explaining some of the cardiac comorbidity in schizophrenia, and could form the basis for development of antipsychotic medications that are free from cardiac side-effects.

Materials and methods

Models of neurons and cardiac pacemaker cells

We apply two multicompartmental L5PC models, “Hay”18 and “Almog”19 model, and two single-compartment SANC models, “Kharche”20 and “Severi”21 model. These models include Hodgkin-Huxley type description for channel activation and inactivation, and hence, changes related to certain ion-channel-encoding gene variants that have been observed in experiments can be directly attributed to a change of one or more parameters of these models. The Hay and Almog neuron models are based on electrophysiological recordings and cell stainings from rat neocortical slices, while the Kharche and Severi models are based on mouse and rabbit data, respectively. For details on the models, see Supplementary information.

Both L5PC models are simulated using NEURON software and Python interface using adaptive time-step integration. The 0-dimensional (point-cell) and 1-dimensional (chain of cells) SANC models are simulated using MATLAB, and the numerical integration is carried out using the variable time-step, stiff differential equation solver ode15s (0-dimensional) or the finite difference method with 0.01 ms time step (1-dimensional). For the 2-dimensional problem, we use the monodomain model24, which is simulated using the finite element method solver FEniCS25. For details on the spatial distribution of parameters in the 2D simulations, see ref.26. Scripts for running L5PC and 0D SANC simulations are publicly available (https://senselab.med.yale.edu/ModelDB/showModel.cshtml?model=187615).

Genes included in the study

We chose the set of SCZ-associated genes as follows: We used the SNP-wise p-value data of ref. 2, and for each gene of interest, determined the minimum p-value among those SNPs that were located in the considered gene. We performed this operation for all genes encoding either subunits of voltage-gated Ca2+, K+, or Na+ channels, subunits of an SK, leak, or hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channel, or Ca2+-transporting ATPases. Several of these genes were found to contain SNPs bearing a high risk of SCZ (p-value smaller than 3 × 10−8 in the data of ref. 2, namely, CACNA1C, CACNB2, CACNA1I, ATP2A2, and HCN1. Using a more relaxed threshold (p-value smaller than 3 × 10−5) extended this set by the genes CACNA1D, SCN1A, SCN9A, KCNN3, KCNS3, KCNB1, KCNMA1, and ATP2B2. This selection was identical to that in our previous work16. In this work, however, we concentrate on the genes that are likely to play a role in both L5PCs and SANCs: these are CACNA1C, CACNB2, CACNA1I, ATP2A2, HCN1, CACNA1D, and SCN1A.

It should be noted that we used the SNPs reported in ref. 2 only to name the above SCZ-related genes, and due to lack of data on their electrophysiological effects, we could not include the actual SCZ-related SNPs. In fact, only 14 of 527 SNPs that had a p-value smaller than 3 × 10−5 were highlighted in online databases (PubMed or SNPedia), and none of these 14 SNPs have yet been studied functionally, either in native or in heterologous cells. Therefore, we searched in PubMed for functional genomic studies reporting the effects of any genetic variant of the above genes, as described below. We only included studies that reported electrophysiological or intracellular Ca2+ imaging data, but we accepted studies performed using all tissue types. Nevertheless, most of the included studies were carried out in embryonic kidney cells.

Gene variants and their downscaled versions

Table 1 lists all studies27–56 that we found where the effects of a variant were measured in a way that could be directly implemented as a parameter change in our models. A more detailed version of this table is given in Supplementary information, Supplementary Table S1. As SCZ is a polygenic disorder, it has been proposed that the disorder will not be induced by any of the SCZ-related SNPs alone, but only when sufficiently many of them are represented. Furthermore, as most of these SNPs are common variants57, it is likely that none of them alone can cause radical cardiac dysfunction—however, their combination could underlie the risk of heart disease that has been observed in SCZ patients. This paradigm was used in this study in a similar fashion as in ref. 16. If the variants described in Supplementary Table S1 altered the neural response or cardiac pacemaking too dramatically (see conditions A1–A5 and B1–B2 in Supplementary information), the changes in the model parameters were brought closer to zero (all in proportion) until a point c ∈[0, 1] where one or more of the scaling conditions were first violated. This downscaling was performed so that those parameters that may receive both negative and positive values were scaled linearly (∆ → c∆, where ∆ denotes the original increment to the underlying parameter as obtained from the literature data) while the parameters that receive only positive values were scaled on the logarithmic scale (Γ → Γc, where Γ denotes the original factor of the underlying model parameter). In other words, the differences in offset and reverse potentials (V offm, V offh) between control and variant neuron were expressed as an additive term ( ± x mV), and this term x was multiplied by a parameter c in the downscaling procedure. By contrast, the differences in all the other model parameters (V slo, τ, P up, γ) between control and variant neuron were expressed as a multiplication (× x), where the downscaling caused this factor x to be exponentiated by the same parameter c.

Table 1.

Table of the genetic variants used in this study

| Gene | Refs. | Type of variant | Cell type |

|---|---|---|---|

| CACNA1C | 27 | L429T, L434T, S435T, S435A, S435P | TSA201 |

| CACNA1C | 27 | L779T, I781T, I781P | TSA201 |

| CACNA1C | 28 | G432X, A780X, G1193X, A1503X | TSA201 |

| CACNA1C | 29 | I781X, C769P, G770P, N771P, I773P, F778P, L779P, A780P, A782P, V783P | TSA201 |

| CACNA1C | 30 | I781T, N785A, N785G, N785L | TSA201 |

| CACNA1C | 31 | Splice variants a1C77-A, -B, -C, and -D | TSA201 |

| CACNA1D | 32,33 | Splice variant 42A | TSA201/HEK293 |

| CACNA1D | 32,33 | Splice variant 43S | TSA201/HEK293 |

| CACNA1D | 34,35 | Homozygous knockout | AV node cells / chromaffin cells |

| CACNA1D | 36 | A749G | TSA201 |

| CACNA1D | 37 | V259D, I750M, P1336R | TSA201 |

| CACNA1D | 38 | rCav1.3scg variant and related mutants | TSA201 |

| CACNB2 | 39 | T11I | TSA201 |

| CACNB2 | 40 | A1B2 vs A1 alone | HEK293 |

| CACNB2 | 41 | Splice variants N1, N3, N4, N5 | HEK293 |

| CACNB2 | 42 | D601E | TSA201 |

| CACNA1I | 43 | Alternative splicing of exons 9 and 33 | HEK293 |

| CACNA1I | 44 | Truncated cDNAs L4, L6, and L9 | HEK293 |

| ATP2A2 | 45,46 | Heterozygous null mutation | Myocytes, embryonic stem cells |

| ATP2A2 | 47 | Dairier’s disease related mutants | HEK293 |

| ATP2A2 | 48 | Dairier’s disease related mutants | HEK293 |

| SCN1A | 49 | Q1489K | Cultured neocortical cell |

| SCN1A | 50 | L1649Q | TSA201 |

| SCN1A | 51 | R859H | TSA201 |

| SCN1A | 51 | R865G | TSA201 |

| SCN1A | 52 | T1174S | TSA201 |

| SCN1A | 53 | M145T | TSA201 |

| HCN1 | 54 | D135W, D135H, D135N | HEK293 |

| HCN1 | 55 | E229A, K230A, G231A, M232A, D233A, S234A, E235G, V236A, Y237A, EVY235-237DDD | Oocytes |

| HCN1 | 56 | WAG-HCN1 | Oocytes |

The scaling conditions were designed such that the variant L5PCs and SANCs retain their baseline firing (L5PC) and pacemaking (SANC) behavior: Conditions A1–A3 require that the variant L5PCs respond with the same numbers of spikes to certain stimuli as the control L5PCs, while conditions A4 and B1 require that the firing (L5PC) or pacemaking (SANC) frequency is not radically changed, and conditions A5 and B2 make sure that the shape of the action potentials is not too different from that of the control cell.

The downscaling was done separately for each applied model; see Supplementary Table S2 for the scaling parameters c obtained for each variant and each model. Supplementary Fig. S1 illustrates the distribution of the variant effects of a single gene, SCN1A, on activation and inactivation voltage-dependency parameters in the Hay model, and shows that the variants span a large array of possible alterations of ion-channel dynamics. This is true also for the variants of other ion-channel-encoding genes (data not shown).

In the following, we present simulation data from the cells implemented with variants of different magnitude and direction, parametrized by variable ϵ. This parametrization is done so that the final effect sizes of the variants are the values of Supplementary Table S2 multiplied or exponentiated by ϵc (see Supplementary information). Variants with and mean that the variant effects on model parameters are half or quarter, respectively, of those of the threshold variants—these variants are, therefore, confirmed to obey the above-mentioned scaling conditions. In addition, we consider the variants and , which represent parameter changes that are opposite to those of and variants.

Results

Pleiotropic effects of Na+ and non-selective ion channel gene variants are analogous

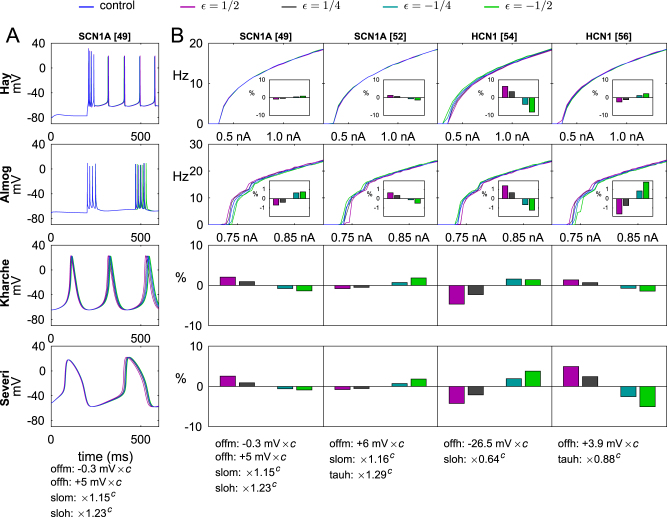

To characterize the joint implications of SCZ-related genes on neuron excitability and cardiac pacemaking, we started by analyzing the effects of the downscaled versions of genetic variants of Na+ and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channel-encoding genes, namely, SCN1A and HCN1. Fig. 1a shows the time course of the membrane potential for several versions of a SCN1A variant, predicted by both L5PC models (when a somatic DC stimulus is applied) and both SANC models (at steady pacemaking). Moreover, Fig. 1b shows the f–I curves, where the firing frequency is plotted against the amplitude of the injected current, and threshold currents for inducing a spike in an L5PC for several SCN1A and HCN1 variants, and the changes these variants cause to the pacemaking frequencies in SANCs.

Fig. 1. Effects of Na+ and HCN channel gene variants on L5PC and SANC excitability are qualitatively similar.

a The membrane-potential time courses of the modeled cells in control cells and Na+ channel variant cells. The L5PCs are stimulated with a somatic DC of amplitude 1.0 nA (Hay model, top panel) or 0.8 nA (Almog model, second from top) to induce stable spiking, while the SANCs rhythmically fire cardiac action potentials without any external stimulus (Kharche model third from top, Severi model on the bottom panel). Different colors represent different scalings of the same variant, parametrized by variable . Variants with and mean that the variant effects on model parameters are half or quarter, respectively, of those of the threshold variants (see threshold parameters c in Supplementary Table S2)—these variants are, therefore, confirmed to obey the above-mentioned scaling conditions. In addition, we consider the variants and , which represent parameter changes that are opposite to those of and variants. Blue: control, magenta:, gray: , cyan: , green: . b The f–I curves and pacemaking rhythms of the modeled cells for different Na+ channel and HCN channel variants. The L5PCs are stimulated with a somatic DC of amplitude ranging from 0.25 to 1.4 nA (Hay model) or 0.7 to 0.9 nA (Almog model), and the firing frequency is plotted against the stimulus amplitude. The insets show the change in threshold current at rest in relation to that of the control neuron (0.350 nA in the Hay model, 0.418 nA in the Almog model: note that the threshold for inducing single spikes at rest is lower than the threshold for inducing continuous spiking). For SANCs, the relative difference from control cell pacemaking rhythm (4.76 Hz in the Kharche model, 2.90 Hz in the Severi model) are shown. Apart for the varied effects of Na+ channel variants on L5PC f–I curves, it can observed that those variants that increase the L5PC firing frequency also mostly increase the pacemaking rhythm in SANCs, and vice versa

The results of Fig. 1 show that the changes in Na+ or HCN channels mostly caused similar effects in L5PCs and SANCs in terms of excitability. If the variant effect was excitatory (lower threshold of firing or steeper slope of f–I curve, i.e., higher gain) in L5PCs, usually the effect in SANCs was excitatory as well (faster pacemaking). We confirmed this observation by changing only one model parameter at a time (see Supplementary Fig. S2). However, the effects of Na+ channel variants on steady-state firing of the Hay-model neuron were usually small and often opposite to the corresponding effects in the Almog-model neuron. Exceptions to the above-mentioned trend arise also in HCN channel variants that affect both the threshold and slope of activation, leading to diverse effects in the two L5PC models (see Supplementary information).

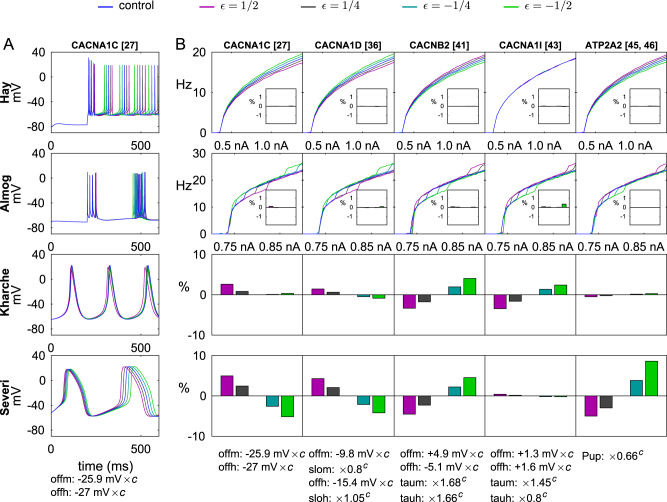

Pleiotropic effects of variants of Ca2+ channel or transporter-encoding genes are non-analogous

Next, we analyzed the implications of the genes that encode subunits of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (CACNA1C, CACNA1D, CACNB2, CACNA1I) or Ca2+ transporters (ATP2A2). In Fig. 2, a representative set of variants of these genes is picked, and their effects on L5PC and SANC behavior is illustrated. In a similar fashion as in Fig. 1, Fig. 2a shows the time course of the membrane potential for different versions of one variant, and Fig. 2b shows the f–I curves and pacemaking frequencies for several variants. A general trend is that variants that increase the pacemaking rhythm in SANCs decrease the firing frequency in L5PCs, and vice versa. This is supported by Fig. 3 showing the mean (averaged over the stimulus amplitudes of Fig. 1) firing frequencies of all implemented variants for the L5PC models and the corresponding pacemaking frequencies for the SANC models, and by Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4 showing results from single-parameter variants. The average firing rates and pacemaking rates of Ca2+ channel and transporter variants were anticorrelated with a correlation coefficient −0.53 to −0.79, while the corresponding correlation coefficients for Na+ and HCN channel variants were 0.47–0.78 (see Table 2). Exceptions to this trend are discussed in Supplementary information, and the reasons for them are illustrated in Supplementary Figs. S5, S6, S7, and S8, where the time courses of different current species are plotted for control and variant neurons.

Fig. 2. Ca2+ channel gene variants typically have opposite effects on L5PC firing and SANC pacemaking.

a The membrane potential time courses in control cells and cells implemented with a CACNA1C variant (the first variant in Supplementary Table S2), see Fig. 1a. b The f–I curves and pacemaking rhythms of the modeled cells implemented with a Ca2+ channel or transporter variant, see Fig. 1b. Apart from the CACNA1I variants that show mixed effects, it can be seen that those variants that increase the pacemaking rhythm in SANCs, decrease the L5PC firing frequency, and vice versa. Variant effects on threshold currents in L5PCs are generally small

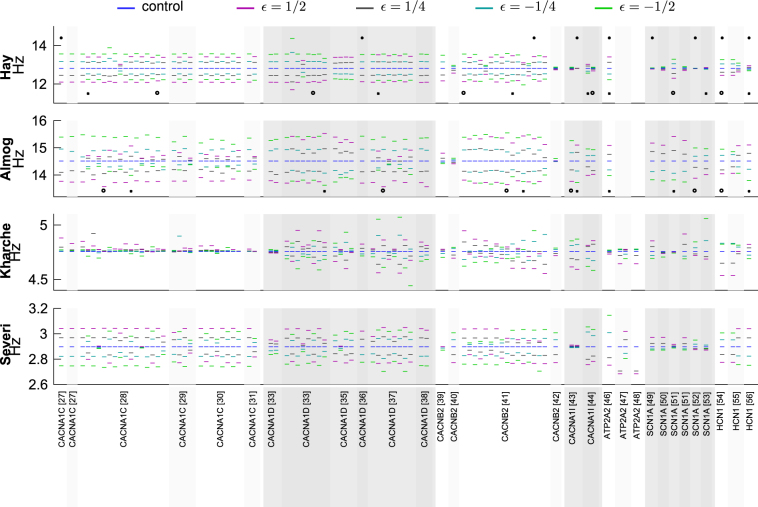

Fig. 3. Overview of variant effects on L5PC firing and SANC pacemaking.

The average firing frequencies and pacemaking rhythms are shown for all variants of Supplementary Table S2. Top panel: Firing rates in the Hay model, averaged over stimulus amplitudes 0.35–1.4 nA. Second panel: Firing rates in the Almog model, averaged over stimulus amplitudes 0.7–0.9 nA. Third panel: Pacemaking rates in the Kharche model. Bottom panel: Pacemaking rates in the Severi model. See Figs. 1 and 2 for more detailed data. Variants shown in Figs. 1 and 2 are highlighted with asterisks, and variants used in combinations of Supplementary Fig. S10 are highlighted with crosses (' × ') and circles (' ∘ ')

Table 2.

Firing frequencies of L5PCs and pacemaking frequencies of SANCs are correlated for Na+ channel and HCN1 variants, but anticorrelated for Ca2+ channel and Ca2+ transporter variants

| (A) Na+ and HCN channel variants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hay | Almog | |

| Kharche | 0.4965 | 0.7477 |

| Severi | 0.5031 | 0.7818 |

| (B) Ca2+ channel and transporter variants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hay | Almog | |

| Kharche | −0.5168 | −0.5971 |

| Severi | −0.7700 | −0.7905 |

| (C) All variants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hay | Almog | Kharche | Severi | |

| Hay | 1 | 0.6896 | −0.4364 | −0.7223 |

| Almog | 0.6896 | 1 | −0.4233 | −0.6501 |

| Kharche | −0.4364 | −0.4233 | 1 | 0.6645 |

| Severi | −0.7223 | −0.6501 | 0.6645 | 1 |

The table shows the correlation coefficients between the firing or pacemaking frequencies of variants (see Fig. 3), as predicted by the different models. A: Only data from SCN1A and HCN1 variants included. B: Only data from CACNA1C, CACNA1D, CACNB2, CACNA1I and ATP2A2 variants included. C: All variants included. The variants that were not applicable for L5PC models (see the Supplementary Table S2 entries corresponding to studies47,48) were omitted. The relatively strong anticorrelations between L5PC and SANC model data in (C) reflect the fact that majority (80) of the variants (94 in total) operated on Ca2+ channels and transporters

The difference in variant effects between L5PC and SANC models is caused by differences in downstream effects of the Ca2+ currents. All four models describe certain aspects of how the intracellular [Ca2+], increased by the current influx through the Ca2+ channels, affects the function of other transmembrane ion channels or exchangers. In the L5PC models, increased intracellular [Ca2+] activates the Ca2+-dependent K+ channels, i.e., the SK channels (and BK channels in the Almog model) that are hyperpolarizing. These channels are traditionally absent from the SANC models, and while recent evidence suggests they may contribute to sinus-node electrophysiology58,59, a well-recognized characteristic of SANC function is that enhanced Ca2+ cycling is an important contributor to increased pacemaking frequency both ex vivo and in vivo 60.

Changes in SANC excitability affect signal propagation

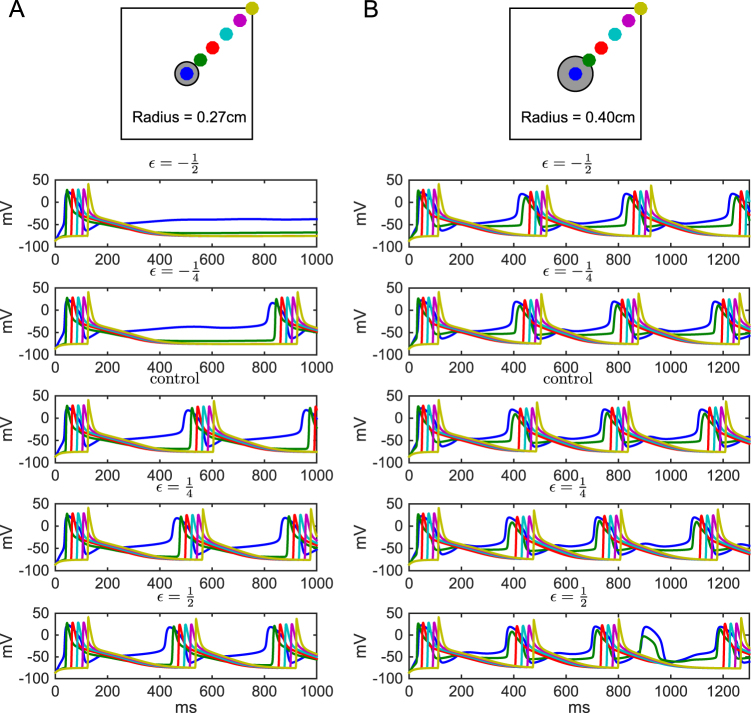

We implemented a simple 1-dimensional model of interconnected SANCs to analyze the effects of the variants on signal conduction. The SANCs were identical, and were connected to each other with a diffusion constant of 6 × 104 µm2/ms (as in ref. 61). In this 1-dimensional model, the SANC components were first voltage-clamped to a hyperpolarized membrane potential (−64 mV), and then a fraction of them was clamped to a depolarized membrane potential ( + 23 mV), and the conduction of this pulse of activation across the SANCs could be observed. Supplementary Fig. S9 shows that subtle variants of Ca2+ channel genes could slightly affect the signal conduction velocity along the sinoatrial node (SAN), and an overview of results for all variants is shown in Supplementary Fig. S11. This propagation is altogether rapid, and, therefore, unlikely to meaningfully alter the speed or sequence of cardiac activation. However, these subtle changes may have larger effects in multiple dimensions and particularly in determining the ability of the SAN to provide sufficient current to activate the surrounding tissue. To test this hypothesis, we applied our variants in a 2-dimensional model including SAN and surrounding atrial tissue. In this experiment, we modeled the SAN tissue using the Severi model and the atrial tissue using the model of ref. 62. We implemented the CACNA1C variant27 (the first entry of Supplementary Table S2) in the SAN tissue using the scaling threshold parameter c = 0.102. Figure 4 shows the initiation and propagation of cardiac action potentials in this composite 2-dimensional model tissue both for control and variant cases. An interesting finding is shown in Fig. 4b, where the variant caused failure of a premature SAN beat to propagate into the atrial tissue when a large SAN (radius r = 0.4 cm) was used. This in turn resulted in an increased beat-to-beat interval, which if frequent enough, would manifest as increased R-R variability and could be clinically identified as an SAN dysfunction.

Fig. 4. Signal propagation from SAN to surrounding atria is altered in a Ca2+ channel variant.

A tissue of size 3 × 3 cm was modeled using a diffusion constant of 1.2 cm2/s in the direction of the monitored fiber and 0.25 cm2/s in the direction orthogonal to this. A spatial resolution of 151 × 151 nodes (0.02 cm) and temporal resolution of ∆t = 0.125 ms was used. The panels show the membrane potential as a function of time at six different locations of the modeled tissue for different scalings of a CACNA1C variant (the first variant of Supplementary Table S2). The center (blue) expresses membrane potential dynamics similar to that seen in single-cell experiments (Figs. 1 and 2), while near the borders (magenta and yellow), the action potentials are sharper and more alike to those presented in ref.62. The left panels (A) show the results in a model tissue with a smaller (radius 0.27 cm) SAN, and the right panels (B) show the results using a larger (radius 0.40 cm) SAN. In the variants with smallest effect ( and ), only the pacemaking frequency is altered, but in other variants, more radical phenotypes are observed. The variant ceases pacemaking in the tissue with smaller SAN, and in the simulations with the larger SAN, all action potentials initiated by the variant SANCs are not successfully transmitted to the atrial tissue

Figure 4a shows that when a small SAN (radius r = 0.27 cm) was combined with the variant, spontaneous SAN activity was silenced. In this case the electrotonic load of the surrounding atrial tissue prevents the current generated by the SANCs from being sufficient to generate a propagating depolarization wave, and thus pacemaking ceases. Such a sharp loss of sinus excitation would be associated with severe (class 1) SAN dysfunction. In an intermediate-sized SAN (radius r = 0.34 cm), by contrast, all variants show a stable pacemaking (data not shown).

Discussion

In this work, using computational modeling we showed how subtle genetic variants of SCZ-associated genes can cause comorbid effects in neuronal and cardiac function. We used models of L5PCs and SANCs due to the biological significance of these cells (in cortical information processing and heart beat initiation, respectively), the high level of biophysical detail with which they are described, and the similarities in expression of the genes studied here. We showed that small changes in the parameters governing the voltage-dependence and time constants of activation and inactivation of different ion channels caused observable effects in both L5PC and SANC function (Figs. 1–3). In the case of Ca2+ channel gene variants, these changes typically had opposite effects on cell excitability in L5PCs compared to SANCs (higher L5PC firing frequency ↔ lower SANC pacemaking frequency, see Fig. 2), while in the case of Na+ or HCN channel variants, the effects were mostly similar (higher L5PC firing ↔ frequency higher SANC pacemaking frequency, see Fig. 1). Our framework is well suited to studying polygenic effects, which is especially important in SCZ: we showed that combinations of subtle variants of different genes can have a large effect on cell excitability (Supplementary Fig. S10). These results are, to our knowledge, the first findings from a polygenic analysis of the pleiotropic effects of genetic variants on neural and cardiac functions.

Our result showing that the gain-of-function Ca2+ channel variants (i.e., variants that increase Ca2+ currents) increase the excitability of SANCs but decrease the excitability of L5PCs, is in line with previous studies. For SANCs, early indirect experimental evidence (e.g., in ref. 63) indicated that larger Ca2+ currents (mediated by an increase in extracellular [Ca2+]) caused faster SAN pacemaking. More recent studies showed that a variety of manipulations that increase whole-cell Ca2+ load also increase SANC pacing frequency, and that their common mechanistic link is spontaneous sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release, which accelerates early SANC depolarization due to Na+-Ca2+ exchange60. The source of SANC pacing is, however, still under debate64. The contexts and molecular players determining the importance of these intracellular Ca2+ fluxes remain hotly debated, but there is little doubt that gain-of-function effects in SANC Ca2+ channels results in more rapid beating due either to direct depolarization or secondarily to Ca2+ release from the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum.

For L5PCs, there are numerous experimental studies analyzing the medium-duration after-hyperpolarization (mAHP) current, which is mediated by SK channels and is strong in L5PCs65, but its Ca2+ channel-dependent inhibitory effect on neuron firing has rarely been compared with the direct excitatory effect of the Ca2+ channels. In ref. 66, the effect of blockade of L-type Ca2+ channels on EPSP amplitude was non-significant (albeit slightly weakening the excitability) compared to control. By contrast, computational studies of L5PCs repeatedly predicted that a decrease in current through Ca2+ channels increase the L5PC excitability (due to the consequent decrease in Ca2+-dependent K+ current), and vice versa. In addition to the present work, this was concluded in our earlier work16 and in an independent study employing a network of L5PCs67, where the blockade of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (especially of those located at the soma) increased the network excitability. Confirming and extending these results may require a spatially detailed neuron model and an extended description of Ca2+ dynamics (cf.65,68).

Apart from L5PCs, the SK-Ca2+ current coupling that reverses the output gain of the Ca2+ currents has been experimentally observed in other types of neurons69. These data could be used to validate the results obtained from our method when applied to other cell types. L5PCs are of particular interest among the types of neuron in the brain due to their role as an integrator of sensory feed-forward and cortical feed-back information17. However, future work should address these research questions in other types of neurons as well, as made possible by the increasing availability of biophysical neuron models70, and models of other pacemaker cells and myocytes in the heart.

The differences in the levels of biophysical detail between the applied models prevent a consistent use of some of our variants. Ca2+ dynamics were described in more detail in the SANC models than in the L5PC models, which reflects the known importance of Ca2+ cycling in SANC function and allowed for more comprehensive analysis of SERCA (encoded by ATP2A2) variants and their effects on pacemaking. None of the models, however, takes into account nanoscale Ca2+ release events, which may crucially affect the cell electrophysiology71. The analyses of genetic effects of ATP2A2 were restricted in L5PC models to one variant45,46, whose functional effects had previously been measured both in terms of SERCA uptake and cytosolic Ca2+ transients. Of these quantities, the effect on SERCA uptake could be directly applied to SANC models, while the effect on cytosolic Ca2+ transients could be applied to L5PC model parameters. Note, however, that the latter effect might be highly dependent on the cell type—the experiments of46 were carried out in myocytes. There is a trend toward the development of increasingly detailed biophysical neuron models and hence a L5PC model incorporating the functions of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), SERCA pump, and relevant Ca2+ signaling molecules could be expected in the near future72. Using such models would mitigate the above-mentioned limitation in our approach.

The I f current has notably different characteristics in the two SANC models. In the Kharche model, the description of the I f current was formulated for HCN4-based currents, which have a very negative half-activation potential (−106.8 mV in the Kharche model) and a less steep slope (16.3 mV). By contrast, in the Severi model the I f current had a much higher half-activation potential (−52.5 mV) and a steeper slope (9.0 mV). The choices concerning the I f current in the Severi model are based on experiments made on rabbit SANCs where expression of both HCN1 and HCN4 were found21,73,74, while the Kharche model refers to experiments made on mouse SANCs where expression of only HCN4 was observed20,75. However, other studies found HCN1 expression also in mouse SANCs76,77—HCN1 is also expressed in human SANCs78. Thus, the contribution of HCN1 variants to SANC electrophysiology can be expected in both mice and humans, the latter contribution being an important assumption underlying our study.

Despite the differences in the voltage-dependencies of the I f current inactivation, both SANC models agree on the fact that the current is most of the time depolarizing (reversal potentials were approximately −24 mV and −4 mV in the Kharche and Severi models, respectively). Moreover, the (depolarizing) amplitude of the I f current is very similar in the two models (0.006 nA in Kharche model and 0.0067 nA in the Severi model, data not shown). Accordingly, the effects of the HCN channel variants on the SANC pacemaking were qualitatively similar in the two models, as shown in Figs. 1 and 3, and Supplementary Fig. S2 (an exception is the second-to-last variant of Fig. 3, whose effects on L5PC models were non-analogous as well, as discussed above).

Our framework is based on downscaling the electrophysiological effects of experimentally studied genetic variants, and as a theoretical approach, it has its limitations. It is not known whether the SCZ-associated SNPs in voltage-dependent ion channel-encoding genes have a measurable effect on the voltage-dependence and kinetics of the underlying channel or not. Furthermore, the magnitudes of the variant effects depend on the conditions used for downscaling the variants, and due to the non-linearity of the neuron models, these conditions may have to be adjusted for each operated model separately to ensure that a single (downscaled) variant does not totally change any fundamental aspect of the cell functionality. Nevertheless, the downscaling framework shows promise as a tool for studying interactions of modest genetic effects, and it can be extended to new cell types and classes of genes. Another limitation of our study stems from the biophysical details that are missing from our models. Like the vast majority of the neuron and cardiac cell models of today, our models do not allow examining the effects of certain biological phenomena controlling the function of ion channels, such as phosphorylation, spatial affinity, or heterogeneous subunit compositions. Extending the models to capture some of these biophysical details would be useful especially in the study of SCZ, as the risk of SCZ has been associated with alterations in not only genes controlling intrinsic electrogenesis (voltage-gated ion channels) and neurotransmission (synaptic ion channels), but also those controlling the calcium signaling machinery affecting the two through protein phosphorylation79. Meanwhile, novel tools in neuroinformatics, such as the automated large-scale classification of ion channel models as presented in ref. 80, could help in comparing the modeled effects of genetic variants between different neuron models and making predictions of the cellular functions in modified baseline conditions such as altered temperatures.

Our results shed light on the correlations between neuronal and cardiac phenotypes in SCZ patients. Due to the complexity of clinical manifestations of SCZ, the neural underpinnings of the symptoms are not well understood, but there is a generic hypothesis of SCZ being a disorder of cortical excitability81,82. To this end, altered L5PC excitability has been proposed as a contributor to the observed SCZ symptoms and phenotypes, such as hallucinations16,17. Altered synaptic function has also been associated to SCZ (suggested both by GWASs and imaging studies), but is out of the scope of the present study. The L5PC functions studied here were restricted to responses to somatic DC—for a more detailed analysis of the effects of the variants on integration of synaptic inputs, we refer to our earlier work16. In this work, we showed that the same subtle genetic variants that altered the L5PC excitability, also altered SANC pacemaking frequency and rate of propagation of the cardiac action potential. While these deviations are specific to pacemaker tissues in the heart, similar pleiotropic effects occurring in the ventricular myocardium could prolong the action potential or increase dispersion of repolarization, and thus be associated with the prolonged QT interval observed in drug-free SCZ patients83. An interesting observation is that the variants may affect the probability of successful signal propagation from the SAN to the surrounding atrial tissue, as shown in Fig. 4b. In these simulations, the variant effects were only implemented in the sinoatrial tissue—were they present also in the atrial tissue, the observed effects on signal propagation could be larger. When this propagation failure is complete, the condition is termed third degree sinoatrial block. More subtle effects include a sporadic block that simply alters P-P variability (and therefore R-R variability) similar to that shown in Fig. 4b. By inducing irregular long pauses in ventricular activation, this type of behavior may contribute to the emergence of ventricular tachycardias, particularly the torsade de pointes that accompanies both acquired and congenital long QT syndrome84,85. This form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia is also associated with the drug-induced long QT syndrome that is a major contraindication of many antipsychotic drugs9.

Our results provide interesting views on the dual effects of SNP-like effects on neuronal and cardiac excitability. While the rare variants of ion-channel-encoding genes often have a disabling or even life-threatening phenotypic effect, the effects of common variants may be subtle and highly specific to certain types of tissue or cell type. The work at hand illustrates the polygenic effects of SCZ-associated genes by borrowing the functional genomic data from gene variants that implicate other, typically larger, phenotypic consequences, and studying the cellular functions under downscaled variant effects. These results provide an important viewpoint on the polygenic alterations of neuronal and cardiac excitability, but eventually, the electrophysiological consequences of the common, SCZ-associated SNPs should be assessed as well. Novel automated cell-patching methods86,87 could help in this vast task.

To conclude, the current findings support the use of a polygenic mathematical modeling approach to understand more of the pathobiology related to the GWAS-revealed SCZ-associated loci. Our results suggest overlapping but non-identical mechanisms through which subtle SNP-like variants of ion-channel and calcium-transporter-encoding genes modulate the intrinsic excitability of neurons and heart cells. This may explain some of the comorbidity between cardiac disease and SCZ, and could facilitate development of antipsychotic drugs with fewer cardiac side-effects.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

NOTUR resources were used for the simulations. Funding: NIH grant 5 R01 EB000790-10, EC-FP7 grant 604102 (“Human Brain Project”), Research Council of Norway (216699, 248778, 223273, 249711, and 248828), South East Norway Health Authority (2017-112), and KG Jebsen Stiftelsen.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Authors' contributions

Designed the study: T.M.M., A.G.E., A.T., A.M.D., O.A.A. Provided data or analytical support: G.T.L., G.T.E. Performed the analysis: T.M.M., G.T.L. Interpreted the results: T.M.M., G.T.L., A.G.E., A.T., A.M.D., G.T.E., O.A.A. Wrote the manuscript: T.M.M., G.T.L., A.G.E., A.T., A.M.D., G.T.E., O.A.A.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41398-017-0007-4) contains supplementary material.

References

- 1.Ripke S, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1150–1159. doi: 10.1038/ng.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ripke S, et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: Is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2007;64:1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard M. Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Psychiatr. 2012;25:83–88. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835035ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatr. 1997;171:502–508. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan MC, Thakore JH. Physical consequences of schizophrenia and its treatment: The metabolic syndrome. Life Sci. 2002;71:239–257. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)01646-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N. Eng. J. Med. 2009;360:225–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reilly J, Ayis S, Ferrier I, Jones S, Thomas S. QTc-interval abnormalities and psychotropic drug therapy in psychiatric patients. The Lancet. 2000;355:1048–1052. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glassman AH, Bigger JT., Jr Antipsychotic drugs: Prolonged QTc interval, torsade de pointes, and sudden death. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2001;158:1774–1782. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sotoodehnia N, et al. Common variants in 22 loci are associated with QRS duration and cardiac ventricular conduction. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1068–1076. doi: 10.1038/ng.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arking DE, et al. Genetic association study of QT interval highlights role for calcium signaling pathways in myocardial repolarization. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:826–836. doi: 10.1038/ng.3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehnart SE, et al. Leaky Ca2+release channel/ryanodine receptor 2 causes seizures and sudden cardiac death in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2230. doi: 10.1172/JCI35346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Splawski I, et al. Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2005;102:8089–8096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502506102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markram H. The Human Brain Project. Sci. Am. 2012;306:50–55. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0612-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iop L. Conference Papers in Science. Vol. 2014, p. 369246 (Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2014).

- 16.M¨aki-Marttunen T, et al. Functional effects of schizophrenia- linked genetic variants on intrinsic single-neuron excitability: A modeling study. Biol. Psychiatr.: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2016;1:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larkum M. A cellular mechanism for cortical associations: An organizing principle for the cerebral cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hay E, Hill S, Schu¨rmann F, Markram H, Segev I. Models of neocortical layer 5b pyramidal cells capturing a wide range of dendritic and perisomatic active properties. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1002107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almog M, Korngreen A. A quantitative description of dendritic conductances and its application to dendritic excitation in layer 5 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:182–196. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2896-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kharche S, Yu J, Lei M, Zhang H. A mathematical model of action potentials of mouse sinoatrial node cells with molecular bases. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;301:H945–H963. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00143.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Severi S, Fantini M, Charawi LA, DiFrancesco D. An updated computational model of rabbit sinoatrial action potential to investigate the mechanisms of heart rate modulation. J. Physiol. 2012;590:4483–4499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.229435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottesman II, Shields J. A polygenic theory of schizophrenia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 1967;58:199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purcell SM, et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460:748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sundnes J., et al. Computing the Electrical Activity in the Heart. Vol. 1 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2007).

- 25.Logg A., Mardal K. A., Wells G. Automated Solution of Differential Equations by the Finite Element Method: The FEniCS Book. Vol. 84. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

- 26.Li P, Lines GT, Maleckar MM, Tveito A. Mathematical models of cardiac pacemaking function. Front. Phys. 2013;1:20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kudrnac M, et al. Coupled and independent contributions of residues in IS6 and IIS6 to activation gating of CaV1.2. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:12276–12284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808402200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Depil K, et al. Timothy mutation disrupts the link between activation and inactivation in Cav1.2 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:31557–31564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hohaus A, et al. Structural determinants of L-type channel activation in segment IIS6 revealed by a retinal disorder. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38471–38477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507013200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stary A, et al. Molecular dynamics and mutational analysis of a channelopathy mutation in the IIS6 helix of Cav1.2. Channels. 2008;2:216–223. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.3.6160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang ZZ, et al. Transcript scanning reveals novel and extensive splice variations in human L-type voltage-gated calcium channel, Cav1.2 α1 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:44335–44343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan BZ, et al. Functional characterization of alternative splicing in the C terminus of L-type CaV1. 3 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:42725–42735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.265207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bock G, et al. Functional properties of a newly iden- tified C-terminal splice variant of Cav1.3 L-type Ca2+channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:42736–42748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Q, et al. Expression and roles of Cav1.3 (α1D) L-type Ca2+channel in atrioventricular node automaticity. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011;50:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.P´erez-Alvarez A, Hern´andez-Vivanco A, Caba-Gonza´lez JC, Albillos A. Different roles attributed to Cav1 channel subtypes in spontaneous action potential firing and fine tuning of exocytosis in mouse chromaffin cells. J. Neurochem. 2011;116:105–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinggera A, et al. CACNA1D de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders activate Cav1.3 L-type calcium channels. Biol. Psychiatr. 2015;77:816–822. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azizan EA, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and CACNA1D underlie a common subtype of adrenal hypertension. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1055–1060. doi: 10.1038/ng.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lieb A, Scharinger A, Sartori S, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Striessnig J. Structural determinants of CaV1. 3 L-type calcium channel gating. Channels. 2012;6:197–205. doi: 10.4161/chan.21002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cordeiro JM, et al. Accelerated inactivation of the L-type calcium current due to a mutation in CACNB2b underlies Brugada syndrome. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009;46:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Massa E, Kelly KM, Yule DI, MacDonald RL, Uhler MD. Comparison of fura-2 imaging and electrophysiological analysis of murine calcium channel α 1 subunits coexpressed with novel β 2 subunit isoforms. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:707–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Link S, et al. Diversity and developmental expression of L-type calcium channel β2 proteins and their influence on calcium current in murine heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:30129–30137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu D, et al. Dual variation in SCN5A and CACNB2b underlies the development of cardiac conduction disease without Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2010;33:274–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murbartia´n J, Arias JM, Perez-Reyes E. Functional impact of alternative splicing of human T-type Cav3.3 calcium channels. J. Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3399–3407. doi: 10.1152/jn.00498.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomora JC, Murbartian J, Arias JM, Lee JH, Perez-Reyes E. Cloning and expression of the human T-type channel Cav3.3: insights into prepulse facilitation. Biophys. J. 2002;83:229–241. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75164-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Periasamy M, et al. Impaired cardiac performance in heterozygous mice with a null mutation in the sarco (endo) plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase isoform 2 (SERCA2) gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:2556–2562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ji Y, et al. Disruption of a single copy of the SERCA2 gene results in altered Ca2+homeostasis and cardiomyocyte function. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:38073–38080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dode L, et al. Dissection of the functional differences between sarco (endo) plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) 1 and 2 isoforms and characterization of Darier disease (SERCA2) mutants by steady-state and transient kinetic analyses. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:47877–47889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306784200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahn W, Lee MG, Kim KH, Muallem S. Multiple effects of SERCA2b mutations associated with Darier’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20795–20801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cest’ele S, et al. Self-limited hyperexcitability: Functional effect of a familial hemiplegic migraine mutation of the Nav1.1 (SCN1A) Na+channel. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7273–7283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4453-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vanmolkot KR, et al. The novel p.L1649Q mutation in the SCN1A epilepsy gene is associated with familial hemiplegic migraine: Genetic and functional studies. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:522–522. doi: 10.1002/humu.9486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volkers L, et al. Nav1.1 dysfunction in genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures-plus or Dravet syndrome. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011;34:1268–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cest’ele S, et al. Divergent effects of the T1174S SCN1A mutation associated with seizures and hemiplegic migraine. Epilepsia. 2013;54:927–935. doi: 10.1111/epi.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mantegazza M, et al. Identification of an Nav1.1 sodium channel (SCN1A) loss-of-function mutation associated with familial simple febrile seizures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2005;102:18177–18182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506818102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishii TM, Nakashima N, Ohmori H. Tryptophan-scanning mutagenesis in the S1 domain of mammalian HCN channel reveals residues critical for voltage-gated activation. J. Physiol. 2007;579:291–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lesso H, Li RA. Helical secondary structure of the external S3-S4 linker of pacemaker (HCN) channels revealed by site-dependent perturbations of activation phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:22290–22297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wemho¨ner K, et al. An N-terminal deletion variant of HCN1 in the epileptic WAG/Rij strain modulates HCN current densities. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2015;8:63. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee SH, et al. Estimating the proportion of variation in susceptibility to schizophrenia captured by common SNPs. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:247–250. doi: 10.1038/ng.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen WT, et al. Apamin modulates electrophysiological characteristics of the pulmonary vein and the sinoatrial node. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;43:957–963. doi: 10.1111/eci.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lai MH, et al. BK channels regulate sinoatrial node firing rate and cardiac pacing in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2014;307:H1327–H1338. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00354.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA, Vinogradova TM. A coupled system of intracellular Ca2+ clocks and surface membrane voltage clocks controls the timekeeping mechanism of the heart’s pacemaker. Circ. Res. 2010;106:659–673. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang H, et al. Mathematical models of action potentials in the periphery and center of the rabbit sinoatrial node. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000;279:H397–H421. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koivuma¨ki JT, Korhonen T, Tavi P. Impact of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release on calcium dynamics and action potential morphology in human atrial myocytes: a computational study. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1001067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seifen E, Schaer H, Marshall J. Effect of calcium on the membrane potentials of single pacemaker fibres and atrial fibres in isolated rabbit atria. Nature. 1964;202:1223–1224. doi: 10.1038/2021223a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lakatta EG, DiFrancesco D. What keeps us ticking, a funny current, a calcium clock, or both? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009;47:157. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stocker M. Ca2+-activated K+channels: Molecular determinants and function of the SK family. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:758–770. doi: 10.1038/nrn1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Faber E. Functional interplay between NMDA receptors, SK channels and voltage-gated Ca2+channels regulates synaptic excitability in the medial prefrontal cortex. J. Physiol. 2010;588:1281–1292. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.185645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Papoutsi A, Sidiropoulou K, Cutsuridis V, Poirazi P. Induction and modulation of persistent activity in a layer V PFC microcircuit model. Front. Neural Circuits. 2013;7:161. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jones SL, Stuart GJ. Different calcium sources control somatic versus dendritic SK channel activation during action potentials. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:19396–19405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2073-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simms BA, Zamponi GW. Neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels: Structure, function, and dysfunction. Neuron. 2014;82:24–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Markram H, et al. Reconstruction and simulation of neocortical microcircuitry. Cell. 2015;163:456–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Macquaide N, et al. Ryanodine receptor cluster fragmentation and redistribution in persistent atrial fibrillation enhance calcium release. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015;108:387–398. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blackwell K. Approaches and tools for modeling signaling pathways and calcium dynamics in neurons. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2013;220:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Altomare C, et al. Heteromeric HCN1–HCN4 channels: a comparison with native pacemaker channels from the rabbit sinoatrial node. J. Physiol. 2003;549:347–359. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.027698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barbuti A, Baruscotti M, Difrancesco D. The pacemaker current: from basics to the clinics. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2007;18:342–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu J, Dobrzynski H, Yanni J, Boyett MR, Lei M. Organisation of the mouse sinoatrial node: structure and expression of HCN channels. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;73:729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moosmang S, et al. Cellular expression and functional characterization of four hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channels in cardiac and neuronal tissues. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:1646–1652. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marionneau C, et al. Specific pattern of ionic channel gene expression associated with pacemaker activity in the mouse heart. J. Physiol. 2005;562:223–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.074047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li N, et al. Molecular mapping of sinoatrial node HCN channel expression in the human heart. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2015;8:1219–1227. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Devor A, et al. Genetic evidence for role of integration of fast and slow neurotransmission in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatr. 2017;22:792–801. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Podlaski WF, et al. Mapping the function of neuronal ion channels in model and experiment. eLife. 2017;6:e22152. doi: 10.7554/eLife.22152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.O’Donnell P. Cortical Deficits In Schizophrenia, p. 219–236 (Springer, 2008).

- 82.Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T. Transcranial brain stimulation in schizophrenia: Targeting cortical excitability, connectivity and plasticity. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20:405–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fujii K, et al. QT is longer in drug-free patients with schizophrenia compared with age-matched healthy subjects. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e98555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Viskin S, et al. Mode of onset of torsade de pointes in congenital long QT syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1996;28:1262–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Viskin S, et al. Arrhythmias in the congenital long QT syndrome: How often is torsade de pointes pause dependent? Heart. 2000;83:661–666. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.6.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ranjan R., et al. Automated Biophysical Characterization of the Complete Rat Kv-ion Channel Family, 2014. Society for Neuroscience Meeting (SfN 2014), Washington, DC, USA. November 15–19, 2014.

- 87.Kodandaramaiah SB, Franzesi GT, Chow BY, Boyden ES, Forest CR. Automated whole-cell patch-clamp electrophys- iology of neurons in vivo. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:585–587. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.