An estimated two billion people worldwide have been infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Specifically, the prevalence of HBV infection is particularly high in Asia, including Japan. HBV reactivation (HBVr) can occur in HBV carriers and in patients with resolved HBV infection who are receiving cancer chemotherapy. HBVr can induce severe flares of hepatitis and lead to fatal fulminant hepatitis. With the increasing availability of rituximab-based regimens, HBVr has become a well-known complication of lymphoma chemotherapy. However, before the era of novel agents, such as proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), there were few reports of HBVr in patients with multiple myeloma (MM). Since the approval of these novel agents, the number of reports has increased1–3. In our previous study of 641 patients with MM, we reported that 9 of 99 (9.1%) patients with resolved HBV infection experienced HBVr4. Furthermore, the cumulative incidences of HBVr at 2 and 5 years were 8% and 14%, respectively. While our previous study concluded that HBVr was not rare, reasonable risk factors were not identified4. Therefore, this nationwide retrospective study aimed to evaluate the actual incidence and risk factors of HBVr in Japanese patients with MM.

This study included patients who were diagnosed with symptomatic MM using the International Myeloma Working Group diagnostic criteria between January 2006 and February 2016 at board certified institutes of the Japanese Society of Hematology. The terminology and definitions used remain the same as in our previous report4. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics review board of each participating institution. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

A multivariate logistic regression model was applied to identify independent risk factors related to HBVr using SAS statistical analysis software (version 9.4.; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The other analyses were performed using the same methods as our previous report4.

This study collected data from 5078 patients, including data on 641 patients evaluated in our previous study, from 76 Japanese hospitals4. All patients had been treated with either novel agents (bortezomib, thalidomide, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, panobinostat, carfilzomib elotuzumab, and ixazomib) or had undergone autologous stem cell transplantation (auto-SCT). Of these patients, 52 (1.0%) were HBV carriers, and 760 (15.0%) exhibited resolved HBV infection. Prophylactic antiviral agents were administered to 46 (88.5%) of the 52 HBV carriers to prevent hepatitis; one of the remaining 6 developed hepatitis.

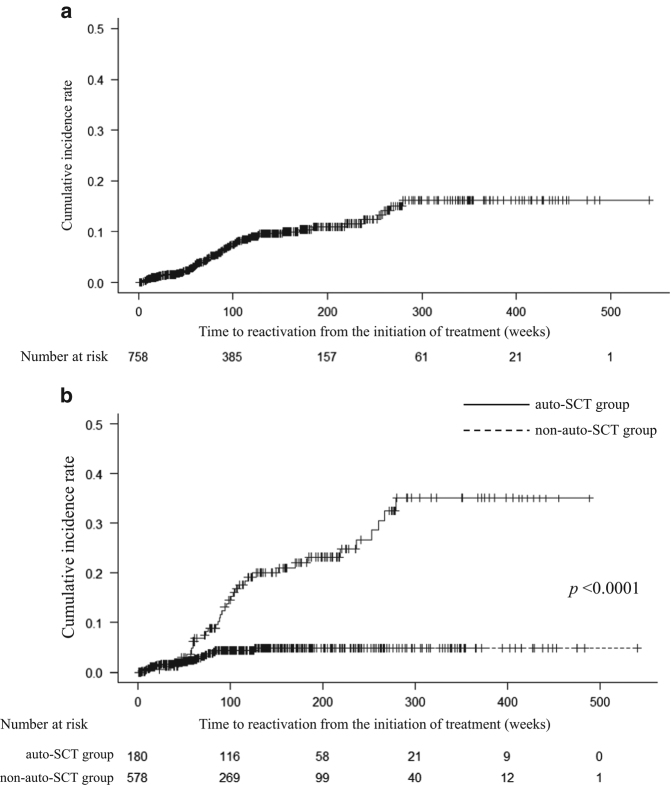

Baseline characteristics of MM patients with resolved HBV infection are shown in Table 1. We identified 180 (23.7%) patients who underwent auto-SCT (156 cases: upfront single, 13 cases: upfront tandem, 8 cases: relapse, 3 cases: upfront and relapse), and 178 patients received high-dose melphalan with or without bortezomib as a conditioning regimen. Sixty-one patients received post-auto-SCT maintenance therapy. During a median follow-up period of 101 weeks (range: 1–541 weeks), 58 of 758 (7.7%) patients with resolved HBV infection experienced HBVr. The cumulative incidence rates of HBVr at 2 and 5 years were 7.9% and 14.1%, respectively (Fig. 1a). Ten of fifty-eight (17.2%) patients with HBVr developed hepatitis, and one died of fulminant hepatitis despite the administration of antiviral agent. In these 10 patients, HBVr was diagnosed after an elevation of alanine aminotransferase levels was observed. Conversely, the other patients who had regular monitoring of HBV-DNA and/or preemptive antiviral therapy according to the Japan Society of Hepatology guidelines did not develop hepatitis5.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with resolved hepatitis B virus infection

| HBV reactivation (n = 58) | No HBV reactivation (n = 702) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.0001 | ||

| Mean (range) | 64 (44–83) | 70 (43–93) | |

| Male, n (%) | 34 (58.6) | 397 (56.6) | 0.7600 |

| MM subtype, n (%) | 0.1769 | ||

| IgG | 30 (51.7) | 376 (53.6) | |

| IgA | 12 (20.7) | 181 (25.8) | |

| IgD | 4 (6.9) | 15 (2.1) | |

| Light chain only | 12 (20.7) | 115 (16.4) | |

| Othersa | 0 (0.0) | 15 (2.1) | |

| Durie–Salmon staging system, n (%) | 0.9108 | ||

| IA | 4 (6.9) | 58 (8.3) | |

| IB | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.9) | |

| IIA | 16 (27.6) | 164 (23.4) | |

| IIB | 1 (1.7) | 26 (3.7) | |

| IIIA | 29 (50.0) | 336 (47.9) | |

| IIIB | 7 (12.1) | 104 (14.8) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.7) | 8 (1.1) | |

| International staging system, n (%) | 0.0943 | ||

| I | 19 (32.8) | 131 (18.7) | |

| II | 21 (36.2) | 297 (42.3) | |

| III | 16 (27.6) | 267 (38.0) | |

| Unknown | 2 (3.4) | 7 (1.0) | |

| HBV serological marker, n (%) | 0.1447 | ||

| Anti-HBs negative | 17 (29.3) | 163 (23.2) | |

| WBC (×10% μL) | 0.4892 | ||

| Mean (range) | 5.2 (2.1–9.3) | 5.3 (1.3–52.9) | |

| Lymphocyte (×10% μL) | 0.3978 | ||

| Mean (range) | 1.6 (0.3–3.1) | 1.5 (0.1–13.9) | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.0250 | ||

| Mean (range) | 3.6 (2.1–5.0) | 3.4 (1.0–5.3) | |

| ALT (IU/L) | 0.2574 | ||

| Mean (range) | 23 (7–73) | 20 (2–160) | |

| Gamma-GTP (IU/L) | 0.0035 | ||

| Mean (range) | 31 (9–115) | 43 (6–540) | |

| Novel agent, n (%) | |||

| Bortezomib | 48 (82.8) | 613 (87.3) | 0.3210 |

| Lenalidomide | 22 (37.9) | 401 (57.1) | 0.0047 |

| Thalidomide | 7 (12.1) | 138 (19.7) | 0.1574 |

| Steroid, n (%) | |||

| Dexamethasone | 53 (91.4) | 648 (92.3) | 0.7973 |

| Prednisolone | 14 (24.1) | 259 (36.9) | 0.0516 |

| Stem cell transplantation, n (%) | |||

| Auto-SCT | 38 (65.5) | 142 (20.2) | <0.0001 |

| Maintenance therapyb | 12(31.6) | 49 (34.5) | 0.7913 |

| Allo-SCT | 1 (1.7) | 2 (0.3) | 0.2122 |

| Follow up (week) | n = 58 | n = 700 | — |

| Median (range) | 74 (4–280) | 105 (1–541) |

Among the 5078 patients with MM, 760 patients exhibited resolved HBV infection. Of these 760 patients, 58 patients experienced HBV reactivation. Univariate analysis revealed that age, elevated serum albumin levels, and auto-SCT treatment were significant risk factors of HBV reactivation. Conversely, the administration of lenalidomide was significantly associated with a lower prevalence of HBV reactivation

Anti-HBs antibodies against hepatitis B surface antigen, WBC white blood cells, ALT alanine aminotransferase, gamma-GTP gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, auto-SCT autologous stem cell transplantation, allo-SCT allogeneic stem cell transplantation

aOthers, includes IgM, non-secretary, and biclonal gammopathy (IgG and IgA)

bMaintenance therapy was compared in patients who received auto-SCT

Fig. 1. Cumulative incidences of HBV reactivation a, and with or without auto-SCT b.

HBV reactivation occurred in 7.6% (58/760) of all patients with resolved HBV infection. The cumulative incidences of HBV reactivation at 2 years and 5 years were 7.9% and 14.1%, respectively a. HBV reactivation occurred in 21.1% (38/180) of patients who received auto-SCT treatment and 3.4% (20/580) of patients who received novel agent treatment. The cumulative incidences at 2 years and 5 years in the auto-SCT group were 16% and 30.6%, respectively. The cumulative incidences at 2 and 5 years in the novel agents group were 4.4% and 4.8%, respectively. The incidence rate was significantly higher in the auto-SCT group than in the novel agents group (p < 0.0001) b

In the univariate analysis, a high incidence of HBVr was observed in groups with elevated serum albumin levels, of younger age, with decreased gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels, and who received auto-SCT (Table 1). Multivariate analysis revealed that auto-SCT was a powerful risk factor for HBVr (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 11.56, 95% confidence interval (CI): 4.61–29.0) (Table 2). The cumulative incidence of HBVr in patients treated with auto-SCT at 2 and 5 years was significantly higher (16% vs. 30.6%, respectively) than those not treated with auto-SCT (4.4% vs. 4.8%, respectively) (log-rank test, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1b). Contrastively, lenalidomide treatment was associated with a low HBVr prevalence (adjusted OR 0.47 (95% CI: 0.26–0.83)) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with hepatitis B virus reactivation

| HBV reactivation (%) (n = 58) | No HBV reactivation (%) (n = 702) | Total (%) (n = 760) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | ||||||||||

| <70 | 40 | (11.0) | 324 | (89.0) | 364 | (47.9) | 2.59 | (1.458–4.611) | 0.52 | (0.200–1.341) |

| ≥70 | 18 | (4.5) | 378 | (95.5) | 396 | (52.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Albumin (g/dL) | ||||||||||

| <3.4 | 39 | (9.4) | 374 | (90.6) | 413 | (54.3) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥3.4 | 19 | (5.5) | 328 | (94.5) | 347 | (45.7) | 1.80 | (1.020–3.177) | 1.50 | (0.820–2.739) |

| Gamma-GTP (IU/mL) | ||||||||||

| <25 | 29 | (8.7) | 304 | (91.3) | 333 | (43.8) | 1.31 | (0.766–2.238) | 1.52 | (0.858–2.693) |

| ≥25 | 29 | (6.8) | 398 | (93.2) | 427 | (56.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Auto-SCT | ||||||||||

| Done | 38 | (21.1) | 142 | (78.9) | 180 | (23.7) | 7.49 | (4.229–13.275) | 11.56 | (4.606–28.994) |

| Not done | 20 | (3.4) | 560 | (96.6) | 580 | (76.3) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Lenalidomide | ||||||||||

| Received | 22 | (5.2) | 401 | (94.8) | 423 | (55.7) | 0.46 | (0.264–0.796) | 0.47 | (0.261–0.830) |

| Not received | 36 | (10.7) | 301 | (89.3) | 337 | (44.3) | 1 | 1 | ||

Multivariate analysis revealed that only auto-SCT was independently associated with a high prevalence of HBV reactivation. In contrast, lenalidomide significantly decreased the incidence of HBV reactivation

aThe adjusted OR was calculated by a conditional logistic regression, which was adjusted for age, albumin levels, gamma-GTP levels, auto-SCT treatment, and lenalidomide treatment

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, gamma-GTP gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, auto-SCT autologous stem cell transplantation

There have only been a few reports of HBVr among MM patients who were treated with lenalidomide or pomalidomide6, but this adverse effect is mentioned in the drug information sheets of both drugs in the EU. In this study, only one patient did not receive auto-SCT or novel agents (except lenalidomide). Lenalidomide is an IMiD that targets cereblon (CRBN) to induce antitumor activity. The argonaute2 (AGO2) is the only member with catalytic activity and plays an essential role within the RNA-induced silencing complex; thus, it regulates small RNA-guided gene splicing processes7. Recently, Xu et al.8 showed that AGO2 was a CRBN binding partner and was negatively regulated by CRBN in MM cells. In the study, administration of lenalidomide significantly increased expression of CRBN and decreased the levels of AGO2 and microRNAs in MM cell lines. Another study reported that the knock down of AGO2 induced decreased levels of HBsAg and HBV-DNA in cells transfected with plasmids of HBV components9. These results suggest that lenalidomide may decrease AGO2 levels and inhibit HBV proliferation in patients with MM.

In our previous study, auto-SCT was not significantly associated with HBVr4; however, in the present study, auto-SCT was shown to be a powerful risk factor for HBVr. This discrepancy could be a result of different samples sizes. Auto-SCT is a well-known risk factor for HBVr10, and a previous Korean retrospective study that analyzed 230 patients with resolved HBV infection similarly reported that auto-SCT significantly increased the prevalence of HBVr in patients with MM1. Conversely, only 17 patients with MM who experienced HBVr were reported from non-Asian regions, 14 (82.4%) of these received auto-SCT. It is possible that auto-SCT is a risk factor for HBVr not only in Asia but also worldwide.

Recently, several guidelines recommend antiviral prophylaxis for patients at high risk of HBVr from the initiation of chemotherapy11, 12. The present study and a prospective study on lymphoma showed that patients who received preemptive antivirals following HBV-DNA monitoring did not experience HBVr-related hepatitis13. Additionally, HBV-DNA monitoring is more economical than antiviral prophylaxis; these results suggest that prophylactic antiviral therapy might not always be recommended in MM.

There are three differences in results between the present study and the previously described Korean study1. First, the cumulative incidence of HBVr in the auto-SCT group was higher in the current study (16 and 7% at 2 years), which could be attributable to the different definitions of HBVr used. In the Korean study, HBVr was defined as the reappearance of HBsAg in the blood; therefore, our definition may lead to earlier and higher incidences of HBVr. The second difference is that the current study observed a longer time between auto-SCT and HBVr1. In the Korean study, all patients who underwent auto-SCT experienced HBVr within 6 months, and the investigators recommended monitoring HBV-DNA levels for at least 24 months after transplantation. In the present study, 6 of the 38 patients who received auto-SCT experienced HBVr after more than 2 years post transplantation (median, 55 weeks; range, 10–250 weeks). Two of these patients were not treated with chemotherapeutic agents after auto-SCT until they exhibited HBVr (maximum, 226 weeks). These results suggest that the appropriate period of HBV-DNA monitoring for patients with MM remains unclear; long-term monitoring may be required to prevent flares of hepatitis, especially among patients treated with auto-SCT. The third difference is that the Korean study, along with several other studies, identified negative or low titers of antibodies against the hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) to be a risk factor of HBVr1, 14. However, there was no significant association between anti-HBs negativity and HBVr in the present study, and serological markers could not be thoroughly assessed because each institution used different assay methods.

Our study had two major limitations. First, the duration of observation was relatively short (approximately 2 years). The therapeutic outcome MM treatment using novel agents has seen significant improvements. The current systematic chemotherapy, including the consolidation and/or maintenance phase15, requires a longer treatment period. There was no significant association between post-transplant maintenance therapy and HBVr in our study (p = 0.7913). However, the actual prevalence of HBVr in MM patients who experienced prolonged treatment could not be determined, as the incidence of HBVr gradually increased up to 5 years (260 weeks) after initiating treatment. Secondly, the relationship between HBVr and allogeneic SCT or recently approved novel agents apart from bortezomib, thalidomide, and lenalidomide, was unclear. The sample size was too small to evaluate the relationship.

In conclusion, this large-scale, nationwide retrospective study showed that HBVr in patients with MM was significantly higher, especially among patients who received auto-SCT. Additional prospective studies with long-term observation periods are needed to evaluate the optimal duration of HBV-DNA monitoring and to develop an effective strategy to prevent HBVr in patients with MM.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the following physicians of the cooperating hospitals for providing the clinical data: Michiaki Koike (Juntendo University Shizuoka Hospital), Hideto Tamura and Keiichi Moriya (Nippon Medical School), Shigeki Ito and Maki Asahi (Iwate Medical University School of Medicine), Yoichi Imai and Junji Tanaka (Tokyo Women’s Medical University), Hiroshi Handa and Hiromi Koiso (Gunma University), Sakae Tanosaki (The Fraternity Memorial Hospital), Yoshihiro Hatta (Nihon University School of Medicine), Jian Hua and Masao Hagihara (Eiju General Hospital), Ilseung Choi (National Hospital Organization Kyushu Cancer Center), Naoko Harada (National Hospital Organization Kumamoto Medical Center), Kensuke Ohta (Osaka Saiseikai Nakatsu Hospital), Toshihiro Fukushima (Kanazawa Medical University Hospital), Yoshitaka Imaizumi (Nagasaki University Hospital), Hiroyuki Kuroda (Steel Memorial Muroran Hospital), Yuichi Nakamura (Saitama Medical University Hospital), Tomoharu Takeoka (Otsu Red Cross Hospital), Mitsufumi Nishio (NTT Higashinihon Sapporo Hospital), Takeshi Yamashita (Keiju Kanazawa Hospital), Msayoshi Kobune (Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine), Nobuhiko Nakamura (Gifu University Hospital), Miyuki Ookura (University of Fukui Hospital), Eriko Sato (Juntendo University Nerima Hospital), Masahiro Onozawa (Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine), Shikiko Ueno (Kumamoto University Graduate School of Medicine), Riko Tsumanuma (Yamagata Prefectural Central Hospital), Hiroyuki Takamatsu (Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medical Science), Naoko Furuya (Tokyo Medical University), Yoshio Saburi (Oita Prefectural Hospital), Nobuhiko Uoshima (Japanese Red Cross Kyoto Daini Hospital), Tsuyoshi Takahashi (Mitsui Memorial Hospital), Satoru Hasuike (Faculty of Medicine, University of Miyazaki), Tadahiko Igarashi (Gunma Cancer Center), Akio Kohno (JA Aichi Konan Kosei Hospital), Kyoko Inokura (Faculty of Medicine, Yamagata University), Shigeru Hoshino (Saitama Red Cross Hospital), Nobuhito Ohno (Ikeda Hospital), Ayumi Numata (Kanagawa Cancer Center), Atsushi Inagaki (Nagoya City West Medical Center), Tohru Takahashi (Tenshi Hospital), Hirotsugu Kojima (Daido Hospital), Kazuki Tanimoto (Fukuoka Red Cross Hospital), Katsumichi Fujimaki (Fujisawa City Hospital), Yasushi Terasaki (Toyama City Hospital), Hirokazu Okumura (Toyama Prefectural Central Hospital), Tsuyoshi Nakamaki (Showa University School of Medicine), Norisato Hashimoto (Tokai University Hachioji Hospital), Masahide Yamazaki (Keiju Medical Center), Masayuki Ohnishi (Niigata Minami Hospital), Akio Saitoh (Fujioka General Hospital), Tomoyuki Imamura (Oita Memorial Hospital), Hiroto Kaneko (Aiseikai Yamashina Hospital), Masahiro Fujiwara (Kashiwazaki General Hospital and Medical Center), Naoki Harada (Chihaya Hospital), Masato Shikami (Daiyukai General Hospital), Takahiro Karasuno (Rinku General Medical Center), Nobuhisa Hirase (Nakatsu Municipal Hospital), Masanobu Nakata (Seirei Hamamatsu General Hospital), Yoshihito Iwahara (National Hospital Organization Kochi National Hospital), Tatsuyuki Hayashi (Tokyo Metropolitan Police Hospital), Sachiya Takemura (Yokohama Ekisaikai Hospital), Masaru Shibano (Sakai City Medical Center), Naoki Takezako (National Hospital Organization Disaster Medical Center). This work was supported by the grant (Takeda Research Support) from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company (to M.S.).

Competing interests

M.S. received research funding from Takeda. K.S. received honoraria from Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Ono Pharmaceutical, and received research funding from Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, Takeda, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, and Daiichi Sankyo. Ta.M. received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Celgene, and Ono Pharmaceutical. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee JY, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in multiple myeloma patients with resolved hepatitis B undergoing chemotherapy. Liver Int. 2015;35:2363–2369. doi: 10.1111/liv.12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, Huang B, Li Y, Zheng D, Zhou Z, Liu J. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with multiple myeloma receiving bortezomib-containing regimens followed by autologous stem cell transplant. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2015;56:1710–1717. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.941833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varma A, et al. Impact of Hepatitis B Core antibody seropositivity on the outcome of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple Myeloma. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23:581–587. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukune Y, et al. Incidence and clinical background of hepatitis B virus reactivation in multiple myeloma in novel agents’ era. Ann. Hematol. 2016;95:1465–1472. doi: 10.1007/s00277-016-2742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drafting Committee for Hepatitis Management Guidelines and the Japan Society of Hepatology. JSH Guidelines for the Management of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Hepatol. Res. 2014;44:1–58. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ataca P, Atilla E, Kircali E, Idilman R, Beksac M. Hepatitis B (HBV) reactivation rate and fate among multiple myeloma patients receiving lenalidomide containing regimens: a single center experience. Blood. 2015;126:5377. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye Z, Jin H, Qian Q. Argonaute 2: a novel rising star in cancer research. J Cancer. 2015;6:877–882. doi: 10.7150/jca.11735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Q, et al. Expression of the cereblon binding protein argonaute 2 plays an important role for multiple myeloma cell growth and survival. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:297. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2331-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes CN, et al. Hepatitis B virus-specific miRNAs and Argonaute2 play a role in the viral life cycle. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moses SE, Lim Z, Zuckerman MA. Hepatitis B virus infection: pathogenesis, reactivation and management in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2011;9:891–899. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phipps C, Chen Y, Tan D. Lymphoproliferative disease and hepatitis B reactivation: challenges in the era of rapidly evolving targeted therapy. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 2017;67:370–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kusumoto S, et al. Monitoring of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA and risk of HBV reactivation in B-cell lymphoma: a prospective observational study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015;61:719–729. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul S, et al. Role of surface antibody in hepatitis B reactivation in patients with resolved infection and hematologic malignancy: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66:379–388. doi: 10.1002/hep.29082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipe B, Vukas R, Mikhael J. The role of maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e485. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]