Abstract

The activity of certain G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and of glutamate N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) is altered in both schizophrenia and depression. Using postmortem prefrontal cortex samples from subjects with schizophrenia or depression, we observed a series of opposite changes in the expression of signaling proteins that have been implicated in the cross-talk between GPCRs and NMDARs. Thus, the levels of HINT1 proteins and NMDAR NR1 subunits carrying the C1 cytosolic segment were increased in depressives and decreased in schizophrenics, respect to matched controls. The differences in NR1 C1 subunits were compensated for via altered expression of NR1 subunits lacking the C1 segment; thus, the total number of NR1 subunits was comparable among the three groups. GPCRs influence the function of NR1 C1-containing NMDARs via PKC/Src, and thus, the association of mu-opioid and dopamine 2 receptors with NR1 C1 subunits was augmented in depressives and decreased in schizophrenics. However, the association of cannabinoid 1 receptors (CB1Rs) with NR1 C1 remained nearly constant. Endocannabinoids, via CB1Rs, control the presence of NR1 C1 subunits in the neural membrane. Thus, an altered endocannabinoid system may contribute to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression by modifying the HINT1-NR1 C1/GPCR ratio, thereby altering GPCR-NMDAR cross-regulation.

Introduction

Neural diseases such as schizophrenia and depression coincide with alterations in the function of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-type ionotropic glutamate receptors (NMDARs). The dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and adenosine systems, as well as metabotropic glutamate receptors, have been implicated in schizophrenia1. The serotonin system was initially related to depression2; however, later studies strongly suggested that it also participates in schizophrenia3,4. Serotonin directly and indirectly regulates dopaminergic neurons5. Thus, serotonin can participate in dopaminergic signaling dysregulation such as that observed in schizophrenic patients. GPCRs influence the strength of synaptic plasticity6 via regulation of NMDAR function. Thus, the increased activity of GPCRs such as dopamine 2 receptors (D2Rs) was initially proposed to decrease NMDAR activity in schizophrenia7–9. Similarly, in depression, the impaired function of mostly serotonergic GPCRs10 was thought to underlie the increases in NMDAR function11–13.

Nevertheless, GPCRs and NMDARs undergo bidirectional regulation wherein GPCRs that enhance NMDAR calcium influx may be negatively controlled by the recruited glutamate signaling, as has been extensively documented in the development of analgesic tolerance via mu-opioid receptors (MORs) (see e.g., ref. 14). A similar mechanism may account for the hypofunction of certain types of serotonergic receptor observed in depressive patients2. Thus, NMDARs appear to play a deterministic role in the onset and consolidation of these mental illnesses15, such as NMDAR hypofunction promotes deregulation of mostly dopamine 2 receptors (increased function) in the striatal and prefrontal regions of schizophrenic patients3,16,17, whereas in depressives NMDAR hyperfunction restrains primarily serotonin signaling in the prefrontal cortex18,19. In support of this notion, the antagonism of NMDARs by ketamine leads to rapid, robust, and relatively sustained antidepressant effects in patients with treatment-resistant major depression, in contrast to the delayed effects observed with the use of traditional antidepressants, e.g., serotonin uptake inhibitors20,21.

Thus, mood stability correlates with certain levels of NMDAR function, and mood instability may appear as a consequence of NMDAR hypo- or hyperfunction. Consequently, the molecular mechanisms implicated in NMDAR regulation play an essential role in determining individual behavior. NMDAR activity stimulates the release of endocannabinoids, which act through cannabinoid type 1 receptors (CB1Rs) thereby restraining NMDAR function22. Thus, the endocannabinoid system appears to be critical in the negative control of NMDAR function, and in the absence of CB1Rs, NMDAR-mediated excitotoxicity increases23.

At molecular level, a series of GPCRs functionally couple with NMDARs via NR1 subunits bearing the regulatory C1 cytosolic segment6, and the tandem histidine triad nucleotide-binding protein 1 (HINT1)/sigma receptor type 1 (σ1R) supports this cross-regulation24. Through this mechanism, cannabinoids promote CB1R coupling to NMDARs and the subsequent co-internalization of CB1Rs together with NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits25,26. Therefore, endocannabinoids by controlling the levels of NR1 C1 subunits may modulate the function of NMDARs. Inadequate endocannabinoid control may produce excess or insufficient dampening of NMDAR activity, thus promoting dopamine signaling, such as in schizophrenia, or diminishing serotonergic activity, as observed in depression. A growing body of evidence associates the dysregulation of the endogenous cannabinoid system with the pathogenesis of schizophrenia27,28, and thus, early cannabis exposure among vulnerable subjects confers an almost twofold increase in the risk of developing this illness29. Moreover, cannabis exposure among individuals with an established psychotic disorder can exacerbate the symptoms of schizophrenia, trigger relapse, and worsen the course of the illness30–32.

The possible relationship between cannabinoids and depression is also evident. Recreational cannabis is commonly believed not to precipitate signs of depression, and in fact it largely diminishes the perception of negative depressive behaviors33,34. A large-scale epidemiological study has found that frequent users of cannabis exhibit a less depressed mood and a more positive affect than non-consumers of cannabis35, and case study reports have indicated that cannabis use promotes antidepressant effects in some clinically depressed individuals36,37. A series of scientific reports have suggested that depression coincides with low levels of endocannabinoid activity38,39. In fact, the targeted deletion of CN1R gene induces depressive symptoms in rodents40, and decreased central endocannabinoid signaling has been observed in several stress-based models of depression in rodents41,42.

Therefore, anomalies that cause schizophrenia and depression may converge on certain molecular substrates, whose intertwined activities maintain the behavior of individuals within the limits of normality. We hypothesize that alterations in NR1 C1 subunits and in HINT1/σ1R proteins are consequences of endocannabinoid/CB1R dysfunctions, which subsequently affects cross-regulation between NMDARs and certain GPCRs. This pathway, together with other anomalies, may contribute to these mental disorders or promote such illnesses in a subset of patients affected by a dysregulated endocannabinoid system. To investigate this possibility, we performed a postmortem comparative study on prefrontal cortical samples from depressive and schizophrenic subjects. The data revealed robust and opposite changes in HINT1 and NR1 C1 protein levels in schizophrenic and depressive subjects, as well as altered associations of GPCRs, such as MOR and D2R, but not of CB1Rs, with NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits.

Materials and methods

Brain tissue samples

Postmortem human brain samples from the prefrontal cortex (Brodmann’s area 9) were obtained from the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) brain collection, according to the national policies of research and ethical review boards for postmortem brain studies at the time the samples were obtained. A total of 72 samples were collected from 24 schizophrenic patients, 24 patients with depression, and 24 normal subjects. Sample size was estimated based on previous studies43. Details about clinical inclusion criteria, sample dissection, storage and toxicological screening have been described previously43. None of the control subjects had a history of psychiatric disorders or had received antipsychotic and/or antidepressant medication, nor did any die as a result of suicide or a neurological disorder. Before assays, the three groups were individually matched for age ( ± 5 years), sex, race, side of the brain, and postmortem interval (PMI) elapsed before obtaining the sample tissue as much as possible. Prefrontal cortices were processed to obtain the synaptosomal fraction and immunoprecipitation assays were performed as previously described44,45. Allocation of each sample of the triplet was blind for the investigator until statistical analysis. Demographic and toxicological information and causes of death are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Primary cortical cell culture

Neuron-enriched mouse cerebral cortical cultures were prepared from the brains of embryonic day-16 wild-type 129 and HINT1 knockout mice. Cerebral cortices were dissociated and seeded (1.25 × 105 cells/cm2) onto multiwell dishes coated with poly-D-lysine. After 3 h, the culture medium was changed to Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27, GlutaMAX and antibiotics (100 IU/ml Penicillin and 100 µg/mL Streptomycin solution) (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). From days 5–7 in vitro, cytosine arabinoside (5 μM) was added to the cultures to eliminate the majority of proliferating non-neuronal cells. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. In some cases, cells were evaluated after transfection for 72 h, with the concentrated lentiviral vector coding the HINT1 protein cDNA.

Statistical analysis

The solubilized membranes obtained from each subject were processed individually, and the blotting data were normalized, when necessary, to the gel loading control, α-tubulin or IgGs used to immunoprecipitate the target GPCR (See Supplementary Fig. S1). Initially, the values corresponding to the schizophrenic (S), depressive (D) and control groups (C) were statistically compared by unpaired tests and the data are presented as the mean ± SEM of N subjects, typically 24 unless otherwise stated. This study was followed by a matched analysis, in which demographic parameters of the individuals, tissue procurement and conservation were considered to form triplets composed of one subject of each S, D, and C groups (see Supplementary Table S1 for description of triplets). For each triplet, the value of C was assigned an arbitrary value of 1, and those of matched S and D were compared to accordingly. In this case, the results are presented as the computed mean and 95% confidence interval, and the statistical paired analysis determined the confidence of the possible differences between S or D groups with respect to the C group.

In both conditions, data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc LSD. Normal distribution and similarity of variances were previously tested. Although subjects were individually matched, the potential influence of age and PMI on results was tested. Because age, but not PMI, appeared to correlate (Pearson’s r coefficient) with some of the protein expression values, ANCOVA was performed when necessary with age at the time of death as a covariate. The presence or absence of suicide was also included as variable in the ANCOVA analysis. In a post-hoc evaluation, schizophrenic subjects were differentiated between antipsychotic-free and antipsychotic-treated according to the toxicological information at death. A similar analysis was performed in depression between antidepressant-free and antidepressant-treated subjects. Statistical analyses were performed using the Sigmaplot/SigmaStat v.13 package (SPSS Science Software, Erkrath, Germany) and InVivo Stat v.3.2 (UK). Significance was defined as two sided p < 0.05.

The use of human and animal tissue was approved by the Ethical Committee for Research of the CSIC (SAF2012-34991 & CAM PROEX 225/14).

Results

The study was performed on postmortem human samples of prefrontal cortices obtained from schizophrenic (S), depressive (D), and control (C) subjects. The tissues were selected so that there were no significant differences with respect to parameters such as average age, postmortem delay and storage time (Supplementary Table S1). We then evaluated a series of signaling proteins that play an essential role in synaptic communication; hence, we determined their levels in synaptosomes obtained from the prefrontal cortices of the subjects. Table 1 shows the proteins and their phosphorylations evaluated in these samples. A significant negative correlation with age was observed for CB1R and HINT1 proteins, and a positive correlation with age was obtained for MOR. The PMI did not correlate with the expression of any of proteins studied. The total levels observed for β-catenin, GSK3β, nervous tissue-specific PKCγ, neural nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), σ1R, NMDAR total NR1 levels, and GPCRs such as MOR, CB1R, serotonin 1A (5HT1AR), serotonin 2A (5HT2AR) and dopamine 2 (D2R) were reasonably consistent with these reported in previous studies performed in prefrontal cortices of schizophrenics and depressives. In our study, each GPCR was immunoprecipitated with an antibody directed to a particular sequence located in the extracellular domain, whereas blotting analysis was performed with another antibody directed against a different amino acid sequence on the receptor. We found that this procedure was more reliable than direct detection on solubilized synaptosomal membranes, particularly for low-abundance receptors, for which antibodies may provide spurious signals45.

Table 1.

Expression, means and 95% confidence intervals, relative to matched controls (value of 1) of signaling proteins and GPCRs in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenic and depressive subjects

| Protein (prefrontal cortex) | Schizophrenia | Depression | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-catenin (total levels) | = 0.94 (0.62–1.26) | = 1.21 (0.60–1.82) | 94 S vs C |

| β-catenin P-S33/S37/T41 (GSK3β) | ↓ 0.76 (0.61–0.92) | = 1.34 (0.77–1.90) | |

| β-catenin P-S552 (Akt) | = 1.14 (0.48–1.81) | ↑ 2.42 (1.19–3.66) | |

| β-catenin P-S675 (PKA) | ↑ 2.34 (1.68–3.00) | ↑ 2.58 (1.11–4.05) | |

| GSK3β (total levels) | = 0.92 (0.65–1.17) | = 1.15 (0.73–1.57) | 94 S vs C |

| GSK3β P-S9 (Akt) | = 0.81 (0.39–1.24) | = 1.62 (0.90–2.33) | 94 S vs C |

| GSK3β P-Y216 | = 0.90 (0.76–1.06) | = 0.96 (0.82–1.10) | |

| PKCγ (total levels) | = 1.01 (0.70–1.34) | = 1.15 (0.72–1.58) | 95 D vs C |

| nNOS (total levels) | = 0.99 (0.89–1.10) | = 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 96 S vs C |

| nNOS P-S1417 (Akt) | ↓ 0.67 (0.45–0.89) | ↑ 1.51 (1.21–1.82) | |

| CaMKII P-T286 | = 0.98 (0.64–1.33) | ↑ 1.96 (1.08–2.84) | |

| σ1R (total levels) | = 0.97 (0.60–1.34) | = 0.88 (0.65–1.11) | |

| HINT1 (total levels) | ↓ 0.56 (0.49–0.63) | ↑ 1.56 (1.17–1.94) | 52 S vs C |

| 54 D vs C | |||

| NMDAR, NR1 (total levels) | = 0.95 (0.77–1.12) | = 1.08 (0.87–1.29) | 97 S vs C |

| 98 D vs C | |||

| NMDAR, NR1 C1 (total levels) | ↓ 0.59 (0.494–0.68) | ↑ 1.47 (1.23–1.71) | |

| MOR (total levels) | = 1.07 (0.87–1.27) | = 1.24 (0.81–1.66) | 99 S vs C |

| CB1R (total levels) | = 1.36 (0.70–2.04) | = 1.25 (0.77–1.75) | 100 S vs C |

| 60 S vs C | |||

| 61 S & D vs C | |||

| 5HT1AR (total levels) | = 1.14 (0.90–1.40) | = 1.08 (0.83–1.20) | 58 D vs C |

| 5HT2AR (total levels) | = 1.03 (0.91–1.16) | = 1.12 (0.96–1.28) | 58 D vs C |

| 59 D vs C | |||

| D2R (total levels) | = 1.11 (0.94–1.29) | = 0.86 (0.64–1.07) | 100 S vs C |

Proteins were determined by western blotting. Equal loading was verified and adjusted vs. α-tubulin, or for immunoprecipitated GPCRs vs. the heavy or light chains, as required, of the biotinylated immunoglobulins targeting the GPCR, which were captured by agarose streptavidin and accompanied the SDS-PAGE procedure. Human samples were matched as described in Methods into triplets containing one depressive, one schizophrenic and one control. Within each triplet, an arbitrary value of 1 was assigned to the control value and data from the schizophrenic and the depressive subjects were then compared to the matched control. Typically, the analysis was done on 24 triplets, with the exception of 5HT1AR and 5HT2AR, which was performed on 10 triplets. The means and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed for the schizophrenic and depressive values (SigmaPlot v.13/Sigmastat). Arrows indicate significant increases or decreases in protein expression vs. the control group, p < 0.05. The symbol = indicates that the 95% CI included the control value of 1. Previous studies that have reported similar results are shown, indicating the groups of the comparison. Additional details are given in the Methods.

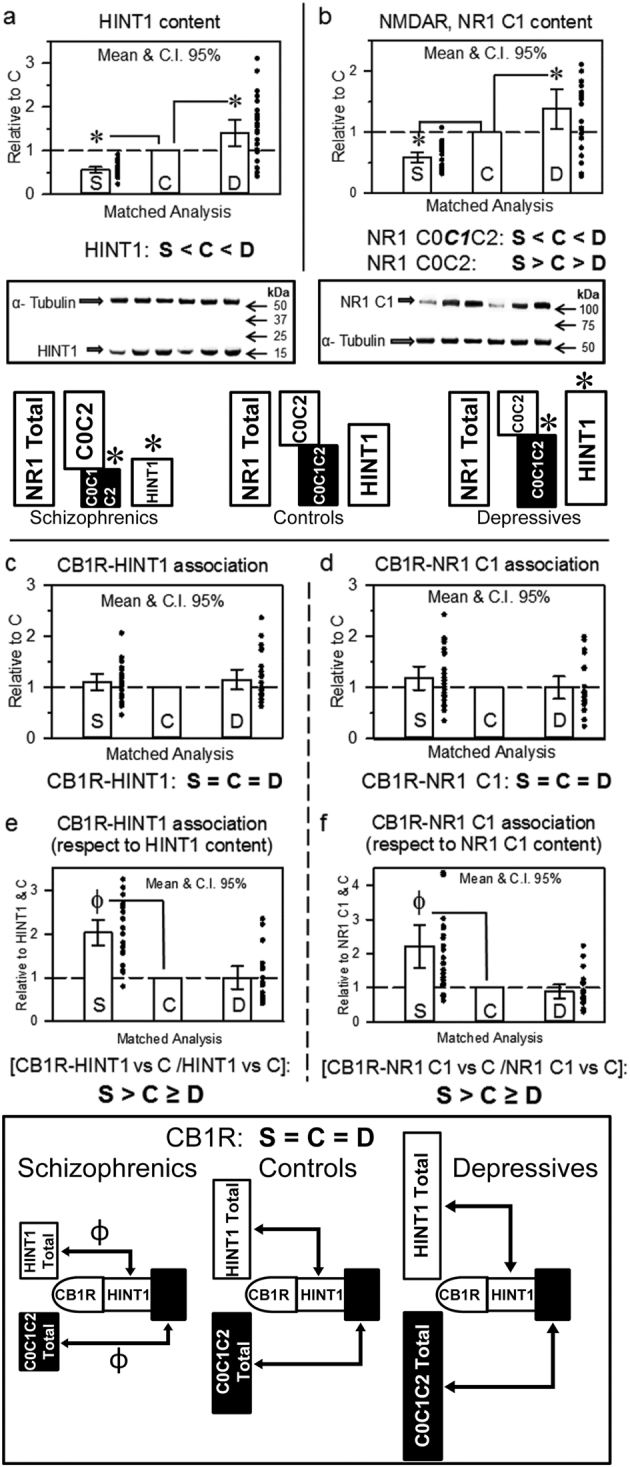

The GSK3β phosphorylation site in β-catenin (S33/S37/T41) decreased by approximately 25% in schizophrenics (F[2,68] = 3.67, p < 0.05), whereas that of Akt (S552) increased 2.4-fold in depressives and that of PKA (S675) increased 2.5-fold in both groups of patients (F[2,68] = 4.64, p < 0.05). Interestingly, certain proteins or their phosphorylation levels changed in both schizophrenics and depressives but in opposite directions (Table 1). Thus, HINT1 (Fig. 1a) (F[2,67] = 12.11, p < 0.0001), NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits (Fig. 1b) (F[2,68] = 12.60, p < 0.0001) proteins and the Akt-mediated activating phosphorylation of nNOS at S1417 increased by approximately 50% in depressives, and decreased 30–50% in schizophrenics (F[2,68] = 15.96, p < 0.0001). The activating auto phosphorylation of CaMKII at T286 augmented almost 2-fold in depressives (F[2,68] = 8.02, p < 0.001). The presence of death by suicide did not modify the findings. Because NMDARs, via calcium and calmodulin, activate CaMKII and nNOS, these observations correlated with increased NMDAR activity in depressives. We and others have shown that only C1 segment-containing NR1 subunits physically interact and form stable complexes with certain GPCRs25,44,46,47 and that this interaction is supported by the HINT1/σ1R complex24.

Fig. 1. HINT1 and NMDAR NR1 C1 subunit levels and their association with CB1Rs in postmortem human prefrontal cortices of schizophrenic and depressive subjects: a comparative study vs. control individuals.

The analysis was first performed for each individual group, schizophrenics (S), depressives (D), and controls (C). The levels of (a) HINT1 and (b) NMDAR NR1 subunits containing C1 cytosolic segment were normalized when necessary to α-tubulin levels. Representative blots are shown. Left, S/C/D triplet 9; right S/C/D triplet 10 (see Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S1). The assays were performed twice, and the average data for each individual were included in the subsequent matched analysis. The values of the schizophrenic and depressive subjects were compared to that of the corresponding matched control of the triplet (assigned an arbitrary value of 1), and for the S and D groups (n = 24) the means (bars), 95% CI (lines) and individual values (points) are shown. Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were performed with age, PMI and suicide as covariates. Inset: diagram indicating differences in HINT1 levels and ratios of the different NR1 subunits in the study groups. *p < 0.05 vs control in LSD post-hoc analyses. CB1R was immunoprecipitated, and CB1R-associated HINT1 (c) and NR1 C1 (d) protein levels were determined by western blotting. Data were normalized when necessary to the signals obtained probing the accompanying anti-CB1R IgGs used for immunoprecipitation with a secondary antibody (mouse anti-rabbit light chain HRP-conjugated monoclonal ab; Millipore #MAB201P). This antibody labels light chains on primary antibodies targeting the GPCR or a co-precipitated protein. Data expression and analyses as in (a) and (b). The CB1R-associated HINT1 and NR1 C1 were related to total HINT1 (e) and NR1 C1 (f) content, respectively. Inset: diagram showing the presence of CB1Rs and their association with HINT1 and NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits relative to the total content of these proteins in the study groups. Ф p < 0.05 vs control in LSD post-hoc analyses

The matched molecular analysis by ANCOVA indicated a significant decrease in HINT1 levels in the prefrontal cortices of schizophrenics (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.05), whereas HINT1 levels increased in depressive subjects (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.01), (Table 1 and Fig. 1a). However, the σ1R levels in the patient groups did not differ from those in the control group (Table 1). The NMDAR NR1 subunit undergoes splicing into four variants: 011/111 C0-C1-C2, 001/101 C0-C2, 010/110 C0-C1-C2’ and 000/100 C0-C2’48. The cytosolic C terminal region of the NR1 subunit is poorly accessible to immunoprecipitation, because it may interact with proteins such as calmodulin, CaMKII, σ1R or HINT149. To circumvent this drawback, we used antibodies against an N terminal extracellular sequence common to the four spliced variants of the NR1 subunit. This particular amino acid sequence does not bind to partner proteins and is free of post translational modifications such as glycosylation or sumoylation.

The total NR1 levels were similar between the three groups of subjects (Table 1). The direct evaluation of NR1 isoforms carrying the C1 segment (for each sample the immunosignal was compared to that of the house keeper α-tubulin), revealed expression differences with schizophrenics (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.01), and depressives (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.05) exhibiting lower and higher levels, respectively, than controls (Fig. 1b). Because the total levels of NR1 subunits were similar among the three groups, changes in NR1 C1 subunit expression were apparently compensated for by subunits lacking the ability to interact with GPCRs. Furthermore, in the schizophrenic group, NR1 C0-C1-C2/2’ subunit levels decreased, whereas NR1 C0-C2/2’ levels increased. In contrast, in the depressive group, NR1 C0-C2/2’ decreased, favoring NMDAR NR1 C1 interactions with GPCRs (Figs. 1a, b). The presence of antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenic patients and antidepressant treatment in depressives did not alter HINT1 or NMDAR NR1 C1 expression.

Cannabinoids negatively regulate NMDAR signaling via CB1Rs; thus, we performed co-immunoprecipitation studies to evaluate the influence of the aforementioned changes on the relation of CB1Rs with NR1 C1. Our study revealed that CB1R levels were comparable among controls, schizophrenics and depressive patients (Table 1). Because σ1R rarely forms stable complexes with the aforementioned proteins in neurons, we were only able to evaluate the formation of GPCR complexes with HINT1 and NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits. Similar amounts of HINT1 and NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits co-precipitated with CB1Rs in all three groups (Figs. 1c, d). Nevertheless, the ratio of CB1Rs coupling to HINT1 (F[2,69] = 8.176, p < 0.0001) and NR1 C1 subunits (F[2,69] = 15.83, p < 0.0001) was clearly altered. Thus, since HINT1 proteins and NR1 C1 subunits were less abundant in schizophrenics, the ratio of CB1R-HINT1 (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.0001) and CB1R-NR1 C1 (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.0001) associations clearly exceeded that in controls. In depressive subjects, these ratios diminished, although without reaching statistical significance (Figs. 1e, f).

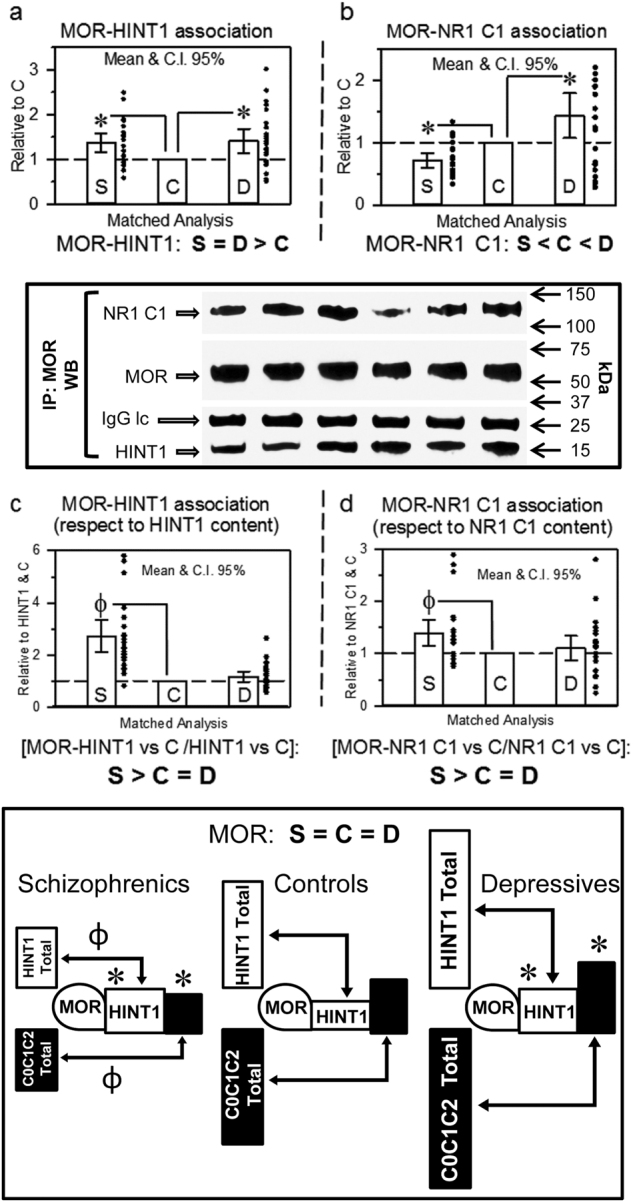

We then explored whether changes in NR1 C1 subunits might affect the physical coupling of GPCRs to NMDARs. The MOR was selected because it forms stable complexes with NR1 C1 subunits14,24 and has not been directly implicated in the mood diseases under study. Our data indicate that the MOR was evenly expressed in all three study groups (Table 1). Notably, the association of MORs with HINT1 proteins significantly increased in schizophrenic and depressive samples (F[2,69] = 6.10, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, schizophrenics showed less association between MORs and NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits and augmented in the depressive group (F[2,69] = 9.98, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2b). These associations of MORs, when normalized to HINT1 and NR1 C1 content, revealed that the proportion of MOR-coupled HINT1 was higher in schizophrenics than in controls (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2c), and schizophrenics were found to have more NR1 C1-coupled MORs than control individuals (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2. MOR association with HINT1 and NR1 C1 subunits in postmortem human prefrontal cortices of schizophrenic and depressive subjects: a comparative study vs. controls.

The MOR was immunoprecipitated and its association with HINT1 (a) and NR1 C1 subunits (b) was determined by western blotting. The regions of the blotting membrane incubated with different antibodies are indicated. The levels of anti-MOR IgG light chain (IgG lc) were used as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. Left, S/C/D triplet 9; right S/C/D triplet 10 (see Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S1). Data expression and analyses as in Fig. 1. The MOR-associated HINT1 and NR1 C1 were compared to total HINT1 (c) and NR1 C1 (d) content, respectively. Inset: diagram showing the presence of MORs and their association with HINT1 and NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits relative to the total content of these proteins in the study groups. *, Ф p < 0.05 vs control in LSD post-hoc analyses

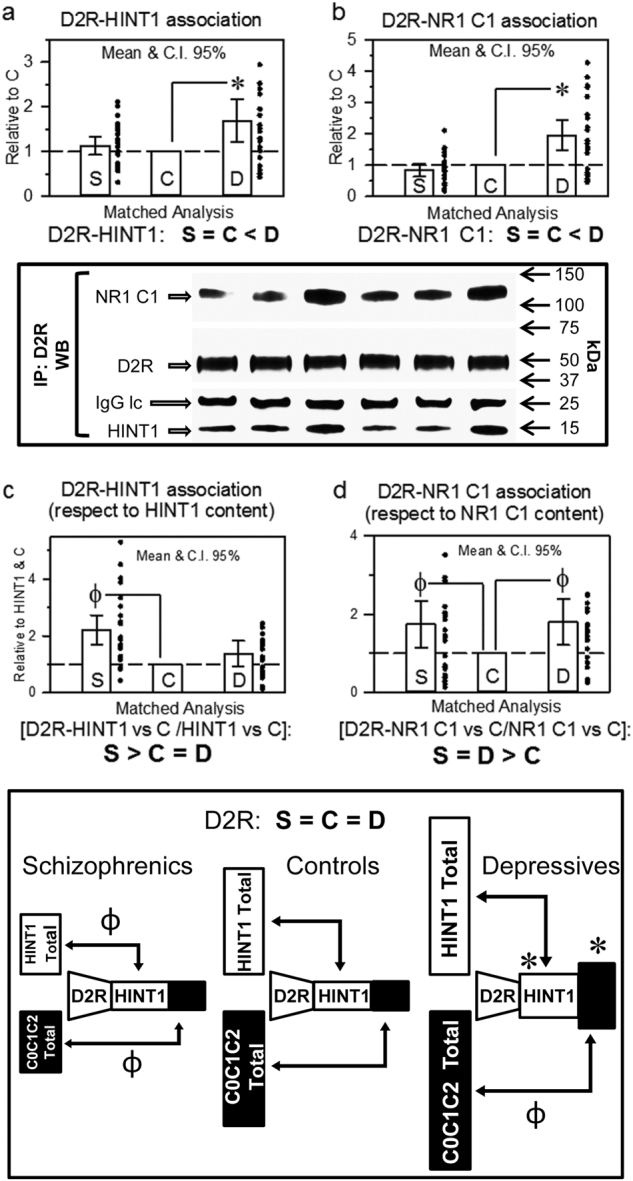

A similar analysis was performed for the D2R receptor, and all three groups showed similar D2R levels (Table 1). In schizophrenics, the association of D2Rs with HINT1 and NR1 C1 subunits was similar to that in controls; however, in depressives, both types of D2R complexes were augmented (D2Rs with HINT1: LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.001; D2Rs with NR1 C1 subunits: LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.0001) (Figs. 3a, b). These values, when normalized to HINT1 expression (F[2,69] = 10.33, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3c), showed a pattern of enhanced expression in schizophrenia similar to that seen for MORs (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.0001). In the case of D2R-NR1 C1, normalizing the data to NR1 C1 content revealed that this association (F[2,69] = 3.62, p < 0.05) increases in both schizophrenics (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.05) and depressives (LSD post-hoc test, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3d). The presence of antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenic patients and antidepressant treatment in depressives did not alter HINT1 or NMDAR NR1 C1 expression. CB1R, MOR and D2R expression and their corresponding associations to HINT1 or NR1 C1 were not modified by the presence of antipsychotic or antidepressant treatment.

Fig. 3. D2R association with HINT1 and NR1 C1 subunits in postmortem human prefrontal cortices of schizophrenic and depressive subjects: a comparative study vs. controls.

The D2R was immunoprecipitated, and its association with HINT1 (a) and NR1 C1 subunits (b) was determined by western blotting. Representative blots are shown. Left, S/C/D triplet 9; right S/C/D triplet 10 (see Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S1). Data expression and analyses as in Figs. 1 and 2. The D2R-associated HINT1 and NR1 C1 were referred to total HINT1 (c) and NR1 C1 (d) content, respectively. Inset: diagram showing the presence of D2Rs and their association with HINT1 and NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits relative to the total content of these proteins in the study groups. *, Ф p < 0.05 vs control in LSD post-hoc analyses

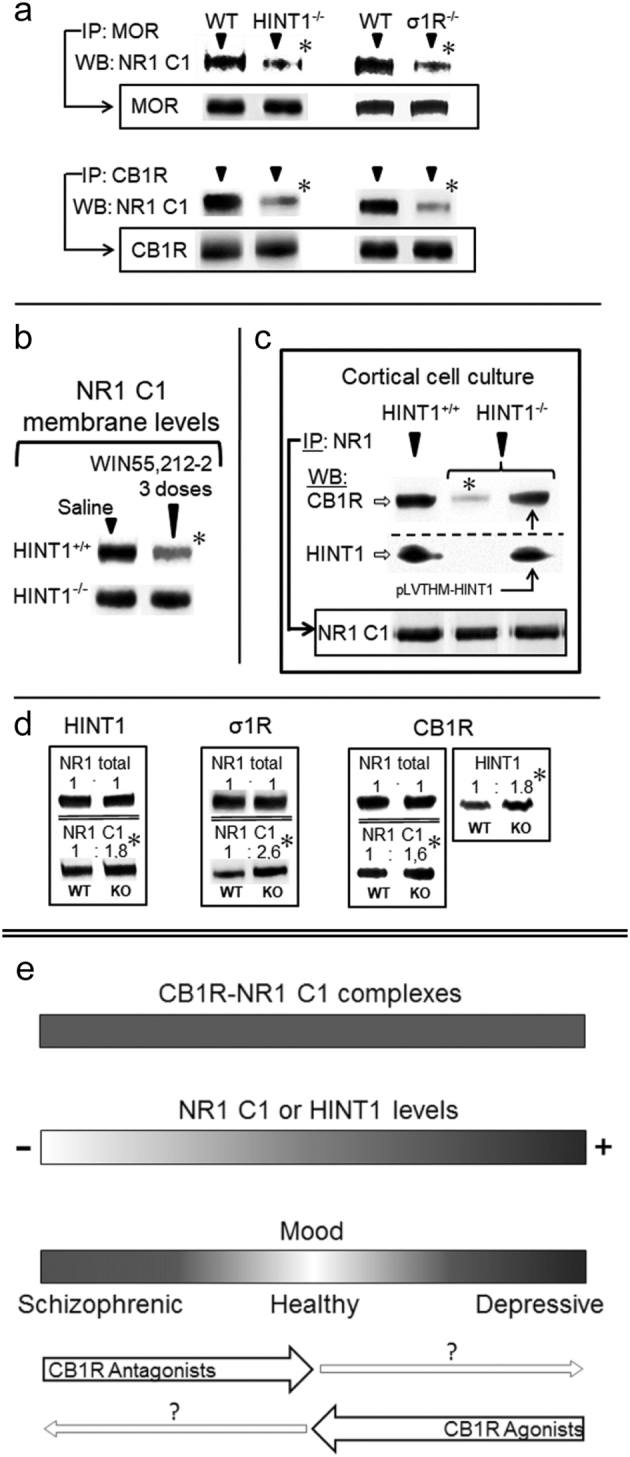

Our previous studies in knockout mice confirmed the essential role of HINT1/σ1R in the cross-talk between certain GPCRs and NMDARs. In Fig. 4, we summarize the findings relevant to the role of cannabinoid system on the negative control of NMDARs. In mice, targeted deletion of the HINT1 or σ1R genes impairs the association of MORs and CB1Rs with NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits25,50 (Fig. 4a). CB1Rs are negative regulators of NMDARs, and our previous studies showed that their activation decreases NR1 C1 subunit levels in the neural plasma membrane, but in mice lacking the HINT1 protein, the cannabinoid agonist WIN55,212-2 does not promote such a reduction in NR1 C1 subunit levels25 (Fig. 4b). In cortical cell cultures from wild-type and HINT1−/− mice, NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity increases and cannabinoids cannot control the activity of NMDARs. In these HINT1−/− cortical cells, we have shown that lentiviral expression of HINT1 restores the association between CB1Rs and NR1 C1 subunits (Fig. 4c) and rescues the neuroprotection mediated by cannabinoids23. In the absence of HINT1 or σ1R, the levels of NR1 C1 subunits increase, whereas total NR1 subunit levels do not change24,51. In mice lacking the CNR1 gene for CB1R, the levels of HINT1 and NR1 C1 increased, whereas total NR1 subunit levels did not differ from those of wild-type mice (Fig. 4d). These observations strongly suggest a role for GPCRs, such as the CB1R, in the changes of HINT1 and NR1 C1 subunit expression observed in schizophrenic and depressive patients.

Fig. 4. Cannabinoids, via CB1Rs negatively control the presence of NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits in neural membranes.

(a) In HINT1−/− and σ1R−/− mice, MOR/CB1R association with NR1 C1 subunits is impaired. IP immunoprecipitation, WB western blot. The immunoprecipitated levels of MORs and CB1Rs are indicated. (b) The cannabinoid agonist WIN55,212-2 promotes the co-internalization of CB1Rs and NR1 C1 subunits. Mice received three intracerebroventricular doses of WIN55,212-2 or saline spaced 90 min apart and were sacrificed 3 h after the last injection. Adapted from ref. 25. (c) The HINT1 protein restores the CB1R-NR1 C1 association. The HINT1 protein was introduced with lentiviral particles. Murine HINT1 was cloned in the pLVTHM vector downstream of the H1 promoter. Lentiviruses (pVLTHM-HINT1 cDNA, psPAX2, pMD2.G) were prepared in HEK-293T cells. Adapted from ref. 23. (d) Total NR1 and NR1 C1 subunits in the frontal cortices of HINT1−/−, σ1R−/− or CB1R−/− mice. For CB1R−/− mice, HINT1 levels are shown. Within each row, knockout (KO) values are compared with those of the respective wild-type (WT) mice (assigned an arbitrary value of 1). The * indicates a significant difference between the study and control group, ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons vs. control group, p < 0.05. Representative blots are shown. Details are given in the references indicated in Results. (e) Diagram showing the possible influence of HINT1/NR1 C1 levels on mental disorders such as schizophrenia and depression

Discussion

Our comparative study revealed that in the prefrontal cortex, the levels of a series of signaling proteins that support cross-regulation between GPCRs and NMDARs decreased in schizophrenics but increased in depressives. The σ1R/HINT1 protein complex regulates the functional coupling between these classes of receptors, and in the absence of either σ1R or HINT1, the communication between GPCRs and NMDARs is impaired or even absent24. In the present study we found no significant changes in σ1R levels; however, our data confirmed that HINT1 levels are lower in schizophrenics52,53, and higher in depressives54. Previous reports have primarily assessed in these mental illnesses total NR1 levels with no reference to spliced variants55,56. Our investigation performed on matched triplets (n = 24) of schizophrenics, depressives and control subjects, found no changes in total NR1 levels but found significant variations respect to controls in isoforms containing the cytosolic GPCR-interacting C1 segment. Accordingly, in response to changing situations, NR1 C0-C1-C2/2’ and NR1 C0-C2/2’ subunits may modify their relative levels without altering total NR1 subunit levels, which probably must be maintained within certain physiological limits. NMDAR activity and NR1 C1 subunits increase in depressives and decreases in schizophrenics, and changes in Akt-mediated nNOS phosphorylation provide an indication of NMDAR function. The NMDAR supplies calcium, which binds to and activates calmodulin. In this scenario, nNOS requires activation by calcium-calmodulin to produce nitric oxide (NO). From this initial point, Akt-mediated phosphorylation at S1417 enhances NO production, and the extent of the positive regulation directly correlates with NMDAR function57.

Using our immunoprecipitation approach to study GPCRs in synaptosomes, we detected no significant changes in the presence of MOR, D2R, 5HT1AR, 5HT2AR or CB1R in prefrontal cortices of schizophrenics or depressives. The level of 5HT2AR in depressives remains a subject of controversy, and whereas some reports have described increases58, others have found no significant changes59. Our data indicated a slight tendency to increase, but without reaching statistical confidence (mean ± 95% CI: 1.12 (0.96 – 1.28), n = 10). Differences in the evaluation techniques and the presence or absence of antidepressant treatment at death could explain some of the discrepancies. With respect to CB1Rs, the use of different techniques apparently leads to dissimilar findings in the prefrontal cortices of schizophrenic subjects. Immunohistochemistry analysis has indicated reductions in CB1R-related signals60,61, whereas these receptors show increases in ligand binding62,63. It is possible that in schizophrenics, an increase in CB1R coupling to G proteins enhances agonist binding to this receptor. Available antibodies for immunochemistry are directed to intracellular domains of GPCRs. Therefore, an increase in the association of signaling proteins such as G proteins with the cytosolic regions of CB1Rs would hamper the access of the antibody used to determine the CB1R levels. Without determining receptor affinity through tissue-costly assays, the data do not necessarily reflect increases in Bmax. Because moderate decreases in CB1R mRNA have also been reported in these patients60, we cannot exclude the possibility that CB1R levels undergo some decreases in the prefrontal cortices of schizophrenics; however, our direct assessment of the CB1R molecule revealed no such change, probably related to experimental limitations.

The NR1 C1 subunit assists NMDARs in the formation of stable complexes with GPCRs such as the MOR, CB1R, D1R and mGlu5a (see e.g., ref. 24). As a result of these associations, and in the absence of GPCR activation, the responsiveness of the GPCR-coupled NMDARs to direct activators diminishes23. This regulatory process depends on the HINT1/σ1R complex, and in HINT1−/− mice, GPCRs only weakly stimulate NMDAR activity24. GPGR activation enhances NMDAR function via non-receptor tyrosine kinases, such as Src and Fyn64, as well as through Ser/Thr kinases, such as PKC and PKA, and in this process, the cytosolic C1 segment of the NR1 subunit also plays an essential role6,65. Thus, the association of MORs and D2Rs with NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits varies, as do the levels of NR1 C1 subunits, with the exception of D2R-NR1 C1 interaction in schizophrenics, which was similar to that in control subjects. The use of typical antipsychotic dopamine antagonists or atypical antipsychotics that increase serotonin 5HT1A receptor and decrease 5HT2A receptor signaling to normalize dopamine function probably restored D2R-NR1 C1 interactions. In fact, although some of the schizophrenic subjects were antipsychotic-free at death, all of them had been or were under antipsychotic treatment. Overall, the changes in the associations of these GPCRs with NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits coincided with alterations in NMDAR activity, which increase in depression and decrease in schizophrenia. Thus, NMDAR-containing NR1 C1 subunits may largely determine the expression of the glutamate symptoms of these diseases. Consequently, alterations in the composition of NR1 subunits influence the extent of GPCR-NMDAR cross-regulation, thereby affecting the GPCR-dependent activation of NMDARs and subsequent NMDAR-mediated negative feedback on GPCR signaling6,14.

The extent of CB1R association with NMDAR NR C1 subunits was comparable between schizophrenics, depressives and control subjects, suggesting that CB1R-NMDAR NR1 C1 coupling must be kept within certain limits to ensure appropriate endocannabinoid control over NMDAR function. This result prompts the question of whether the mechanism that controls HINT1 and NR1 C1 levels is associated with the function of CB1Rs. The serotonin 5HT1A receptor, the dopamine D3 and D4 receptors, α1 and α2 adrenergic receptors, and probably other GPCRs as well, negatively influence NMDAR function66–69. Among the candidates that may regulate in humans HINT1/NR1 C1 levels, the serotonin and endocannabinoid systems are important regulators of mood and emotions and are notable for being consistently related to both schizophrenia and depression2,3,32,70. Notwithstanding, current literature provides most convincing evidence of endocannabinoids playing an essential role in the regulation of glutamate NMDAR function. Cannabinoids decrease the strength of NMDAR signaling by regulating signaling pathways that converge intracellularly with those triggered by this glutamate receptor71. Interestingly, the CB1R can establish HINT1- and σ1R-dependent interactions with NMDAR NR1 C1 subunits and consequently exert negative control on NMDAR calcium influx, zinc metabolism and excitotoxicity23,24.

The notion that CB1Rs localize almost exclusively to presynaptic terminals, which exhibit low presence of NMDARs, may diminish the physiological relevance of in vitro and ex vivo observations showing the HINT1-mediated CB1R physical interaction with NR1 C1 subunits. Initially, the CB1R was described primarily in axon terminals; however, most recent studies have challenged this dogma72. Although the CB1R is concentrated in axons (pre-synapse), immunocytochemical and ultrastructural studies have demonstrated its presence in the somatodendritic compartment (post-synapse), both at the spinal73,74 and supraspinal levels75,76, and it co-localizes with NMDARs and PSD95 proteins25. Most newly synthetized CB1Rs first appear in postsynaptic structures such as somata and dendrites, and from this cellular compartment they are transported through endocytosis and recycling to axons, where functional CB1R accumulates in the presynaptic membrane77. Presynaptic CB1R inhibits calcium entry and consequently depresses neurotransmitter release78, and postsynaptic CB1R inhibits calcium permeation in soma and dendrites79. In the somatodendritic compartment, interaction between CB1Rs with other GPCRs such as the D2R80 and calcium channels such as NMDARs diminishes CB1R endocytosis26,79. The activity of endo- and exocannabinoids on these complexes leads to the co-internalization of CB1Rs and NR1 C1 subunits25,81.

Thus, cannabinoids influence NMDAR subunit composition and consequently NMDAR function, which is altered in schizophrenia and depression. There is no significant association between mutations in the CNR1 gene and the predisposition to develop schizophrenia82. However, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in CB1R can increase the presence of neuroticism and susceptibility to developing a depressive episode after exposure to life stress83 and confer an increased risk of antidepressant resistance84. In the prefrontal cortices of schizophrenic or depressive subjects, no significant changes in CB1R abundance were detected, thus suggesting a role for endocannabinoids in the CB1R-mediated variations in NR1 C1 levels observed in these patients. In fact, anandamide (AEA) and palmitylethanolamide levels increase in the blood85 and cerebrospinal fluid86,87 of schizophrenics, and in major depression, the circulating levels of endocannabinoids significantly decrease88,89. In clinical trials for the treatment of obesity with the CB1R antagonist rimonabant, a significant proportion of individuals manifested symptoms of anxiety and depression90,91. Notably, deficient endocannabinoid signaling also appears to precipitate a “depressive-like” phenotype in rodents38. Indeed, CB1R−/− mice exhibit depressive-like and anxiety-like behaviors in several behavioral paradigms92,93, and in our study, the HINT1 and NR1 C1 subunit levels increased in these mice.

Thus, pharmacological interventions targeting the endocannabinoid system may be of therapeutic interest. The use of CB1R antagonists in schizophrenia is under consideration, and some reports have compared their effects with those of antipsychotic drugs, but given the relationship of CB1Rs with NMDARs these drugs better alleviated negative symptoms, and displayed less ability to counteract the dopamine-related positive symptoms32. Assuming that deficient endocannabinoid signaling contributes to depression, the adequate improvement of this system may produce antidepressant effects. In line with this hypothesis, both the direct and the indirect activation of CB1Rs produce behavioral and biochemical responses that are consistent with the effects of conventional antidepressants38.

In light of the quantitative differences observed in our study, parameters that support healthy normal behavior are closer to those of depressives than to those of schizophrenics (Fig. 4e). Thus, the limits of healthy mood lie between, but not necessarily midway between, the schizophrenic and depressive poles. Stimulating the endocannabinoid system, e.g., with CB1R agonists, would ameliorate depressive symptoms, and treatment with antagonists would reduce those of schizophrenia. The possible negative consequences of such exogenous CB1R ligands might be mitigated by the physiology of normal individuals, but preexisting vulnerabilities would displace mood equilibrium to either pole. The present study offers new perspectives on the analysis and comprehension of the molecular alterations that cause these illnesses and brings to fore the relevance of the interactions between GPCRs and NMDARs under the control of endocannabinoids in maintaining what is considered a normal mood.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants of MINECO, SAF-2015-65420R (JGN), SAF-2009-08460 (JJM) and “Plan Nacional de Drogas” 2014-012 (PSB). We would like to thank Gabriela de Alba and Carmelo Aguado for their excellent technical assistance. The authors thank the staff members of the Basque Institute of Legal Medicine for their collaboration in the study. Knockout mice were generously provided by J.B. Wang, Univ. of Maryland, USA (HINT1−/− mice); Esteve labs, Barcelona, Spain (σ1R−/− mice); M. Guzman, Univ. Complutense Madrid, Spain (CNR1−/− mice).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41398-017-0029-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Howes O, McCutcheon R, Stone J. Glutamate and dopamine in schizophrenia: an update for the 21st century. J. Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:97–115. doi: 10.1177/0269881114563634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann JJ, Brent DA, Arango V. The neurobiology and genetics of suicide and attempted suicide: a focus on the serotonergic system. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:467–477. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meltzer HY, Massey BW. The role of serotonin receptors in the action of atypical antipsychotic drugs. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2011;11:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abi-Saab W, et al. Ritanserin antagonism of m-chlorophenylpiperazine effects in neuroleptic-free schizophrenics patients: support for serotonin-2 receptor modulation of schizophrenia symptoms. Psychopharmacology. 2002;162:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di GG, Esposito E, Di MV. Role of serotonin in central dopamine dysfunction. Cns. Neurosci. Ther. 2010;16:179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rojas A, Dingledine R. Ionotropic glutamate receptors: regulation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013;83:746–752. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.083352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mechri A, et al. Glutaminergic hypothesis of schizophrenia: clinical research studies with ketamine. Encephale. 2001;27:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristiansen LV, Huerta I, Beneyto M, Meador-Woodruff JH. NMDA receptors and schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2007;7:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moghaddam B, Javitt D. From revolution to evolution: the glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia and its implication for treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:4–15. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charney DS. Monoamine dysfunction and the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 14):11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathews DC, Henter ID, Zarate CA. Targeting the glutamatergic system to treat major depressive disorder: rationale and progress to date. Drugs. 2012;72:1313–1333. doi: 10.2165/11633130-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naughton M, Clarke G, O’Leary OF, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. A review of ketamine in affective disorders: current evidence of clinical efficacy, limitations of use and pre-clinical evidence on proposed mechanisms of action. J. Affect. Disord. 2014;156:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutschenbaur L, et al. Role of calcium, glutamate and NMDA in major depression and therapeutic application. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2016;64:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garzón J, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Sánchez-Blázquez P. Direct association of Mu-opioid and NMDA glutamate receptors supports their cross-regulation: molecular implications for opioid tolerance. Curr. Drug. Abus. Rev. 2012;5:199–226. doi: 10.2174/1874473711205030199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poels EM, et al. Imaging glutamate in schizophrenia: review of findings and implications for drug discovery. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:20–29. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence. Mol. Psychiatry. 2005;10:40–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javitt DC. Glutamate and schizophrenia: phencyclidine, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, and dopamine-glutamate interactions. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2007;78:69–108. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin LL, Smith DJ. Ketamine inhibits serotonin synthesis and metabolism in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 1982;21:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(82)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto S, et al. Subanesthetic doses of ketamine transiently decrease serotonin transporter activity: a PET study in conscious monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:2666–2674. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dang YH, et al. Targeting of NMDA receptors in the treatment of major depression. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014;20:5151–5159. doi: 10.2174/1381612819666140110120435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutta A, McKie S, Deakin JF. Ketamine and other potential glutamate antidepressants. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsicano G, et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptors and on-demand defense against excitotoxicity. Science. 2003;302:84–88. doi: 10.1126/science.1088208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vicente-Sánchez A, Sánchez-Blázquez P, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Garzón J. HINT1 protein cooperates with cannabinoid 1 receptor to negatively regulate glutamate NMDA receptor activity. Mol. Brain. 2013;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodríguez-Muñoz M, et al. The ON:OFF switch, σ1R-HINT1 protein, controls GPCR-NMDA receptor cross-regulation: implications in neurological disorders. Oncotarget. 2015;6:35458–35477. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sánchez-Blázquez P, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Vicente-Sánchez A, Garzón J. Cannabinoid receptors couple to NMDA receptors to reduce the production of NO and the mobilization of zinc induced by glutamate. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2013;19:1766–1782. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sánchez-Blázquez P, et al. The calcium-sensitive Sigma-1 receptor prevents cannabinoids from provoking glutamate NMDA receptor hypofunction: implications in antinociception and psychotic diseases. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:1943–1955. doi: 10.1017/S1461145714000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Sánchez-Blázquez P, Merlos M, Garzón-Niño J. Endocannabinoid control of glutamate NMDA receptors: the therapeutic potential and consequences of dysfunction. Oncotarget. 2016;7:55840–55862. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez-Blázquez P, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Garzón J. The cannabinoid receptor 1 associates with NMDA receptors to produce glutamatergic hypofunction: implications in psychosis and schizophrenia. Front. Pharmacol. 2014;4:169. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sewell RA, Ranganathan M, D’Souza DC. Cannabinoids and psychosis. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2009;21:152–162. doi: 10.1080/09540260902782802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho BC, Wassink TH, Ziebell S, Andreasen NC. Schizophr. Res. 2011;128:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rapp C, et al. Cannabis use and brain structural alterations of the cingulate cortex in early psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2013;214:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kucerova J, Tabiova K, Drago F, Micale V. Recent Pat. CNS Drug. Discov. 2014;9:13–25. doi: 10.2174/1574889809666140307115532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnelle M, Grotenhermen F, Reif M, Gorter RW. Results of a standardized survey on the medical use of cannabis products in the German-speaking area. Forsch. Komplement. 1999;6(Suppl 3):28–36. doi: 10.1159/000057154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prentiss D, Power R, Balmas G, Tzuang G, Israelski DM. Patterns of marijuana use among patients with HIV/AIDS followed in a public health care setting. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2004;35:38–45. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denson TF, Earleywine M. Decreased depression in marijuana users. Addict. Behav. 2006;31:738–742. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruber AJ, Pope HG, Jr., Brown ME. Do patients use marijuana as an antidepressant? Depression. 1996;4:77–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-7162(1996)4:2<77::AID-DEPR7>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blaas K. Treating depression with cannabinoids. Cannabinoids. 2008;3:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorzalka BB, Hill MN. Putative role of endocannabinoid signaling in the etiology of depression and actions of antidepressants. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;35:1575–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill MN, et al. The therapeutic potential of the endocannabinoid system for the development of a novel class of antidepressants. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009;30:484–493. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill MN, Gorzalka BB. Is there a role for the endocannabinoid system in the etiology and treatment of melancholic depression? Behav. Pharmacol. 2005;16:333–352. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill MN, et al. Regional alterations in the endocannabinoid system in an animal model of depression: effects of concurrent antidepressant treatment. J. Neurochem. 2008;106:2322–2336. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reich CG, Taylor ME, McCarthy MM. Differential effects of chronic unpredictable stress on hippocampal CB1 receptors in male and female rats. Behav. Brain. Res. 2009;203:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rivero G, et al. Brain RGS4 and RGS10 protein expression in schizophrenia and depression. Effect of drug treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2013;226:177–188. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2888-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Sánchez-Blázquez P, Vicente-Sánchez A, Berrocoso E, Garzón J. The Mu-opioid receptor and the NMDA receptor associate in PAG neurons: implications in pain control. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:338–349. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garzón J, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Sánchez-Blázquez P. Morphine alters the selective association between mu-opioid receptors and specific RGS proteins in mouse periaqueductal gray matter. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:853–868. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fiorentini C, Gardoni F, Spano P, Di LM, Missale C. Regulation of dopamine D1 receptor trafficking and desensitization by oligomerization with glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20196–20202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perroy J, et al. Direct interaction enables cross-talk between ionotropic and group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:6799–6805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zukin RS, Bennett MV. Alternatively spliced isoforms of the NMDARI receptor subunit. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:306–313. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93920-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodríguez-Muñoz M, et al. The sigma1 receptor engages the redox-regulated HINT1 protein to bring opioid analgesia under NMDA receptor negative control. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2015;22:799–818. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sánchez-Blázquez P, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Berrocoso E, Garzón J. The plasticity of the association between mu-opioid receptor and glutamate ionotropic receptor N in opioid analgesic tolerance and neuropathic pain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013;716:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garzón-Niño J, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Cortés-Montero E. Increased PKC activity and altered GSK3beta/NMDAR function drive behavior cycling in HINT1-deficient mice: bipolarity or opposing forces. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:43468. doi: 10.1038/srep43468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varadarajulu J, et al. Differential expression of HINT1 in schizophrenia brain tissue. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012;262:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vawter MP, et al. Microarray analysis of gene expression in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Schizophr. Res. 2002;58:11–20. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martins-de-Souza D, et al. Identification of proteomic signatures associated with depression and psychotic depression in post-mortem brains from major depression patients. Transl. Psychiatry. 2012;2:e87. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catts VS, Lai YL, Weickert CS, Weickert TW, Catts SV. A quantitative review of the postmortem evidence for decreased cortical N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor expression levels in schizophrenia: How can we link molecular abnormalities to mismatch negativity deficits? Biol. Psychol. 2016;116:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feyissa AM, Chandran A, Stockmeier CA, Karolewicz B. Reduced levels of NR2A and NR2B subunits of NMDA receptor and PSD-95 in the prefrontal cortex in major depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;33:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waxman EA, Lynch DR. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subtype mediated bidirectional control of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29322–29333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502080200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shelton RC, Sanders-Bush E, Manier DH, Lewis DA. Elevated 5-HT 2A receptors in postmortem prefrontal cortex in major depression is associated with reduced activity of protein kinase A. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1406–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muguruza C, et al. Evaluation of 5-HT2A and mGlu2/3 receptors in postmortem prefrontal cortex of subjects with major depressive disorder: effect of antidepressant treatment. Neuropharmacology. 2014;86:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eggan SM, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Reduced cortical cannabinoid 1 receptor messenger RNA and protein expression in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2008;65:772–784. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eggan SM, Stoyak SR, Verrico CD, Lewis DA. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor immunoreactivity in the prefrontal cortex: comparison of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2060–2071. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dean B, Sundram S, Bradbury R, Scarr E, Copolov D. Studies on [3H]CP-55940 binding in the human central nervous system: regional specific changes in density of cannabinoid-1 receptors associated with schizophrenia and cannabis use. Neuroscience. 2001;103:9–15. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Newell KA, Deng C, Huang XF. Increased cannabinoid receptor density in the posterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Exp. Brain. Res. 2006;172:556–560. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0503-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salter MW, Kalia LV. Src kinases: a hub for NMDA receptor regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:317–328. doi: 10.1038/nrn1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu WY, et al. G-protein-coupled receptors act via protein kinase C and Src to regulate NMDA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:331–338. doi: 10.1038/7243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X, Zhong P, Gu Z, Yan Z. Regulation of NMDA receptors by dopamine D4 signaling in prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:9852–9861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09852.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuen EY, et al. Serotonin 5-HT1A receptors regulate NMDA receptor channels through a microtubule-dependent mechanism. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5488–5501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1187-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu W, et al. Adrenergic modulation of NMDA receptors in prefrontal cortex is differentially regulated by RGS proteins and spinophilin. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18338–18343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604560103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jiao H, et al. Dopamine D(1) and D(3) receptors oppositely regulate. J. Neurochem. 2007;103:840–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parolaro D, Realini N, Vigano D, Guidali C, Rubino T. The endocannabinoid system and psychiatric disorders. Exp. Neurol. 2010;224:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Q, Bhat M, Bowen WD, Cheng J. Signaling pathways from cannabinoid receptor-1 activation to inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid mediated calcium influx and neurotoxicity in dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;331:1062–1070. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Busquets, G. A., Soria-Gomez, E., Bellocchio, L. & Marsicano, G. Cannabinoid receptor type-1: breaking the dogmas. F1000Res5, F1000 Faculty Rev–990, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Hohmann AG, Briley EM, Herkenham M. Pre- and postsynaptic distribution of cannabinoid and mu opioid receptors in rat spinal cord. Brain. Res. 1999;822:17–25. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)01321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ong WY, Mackie K. Neuroscience. 1999;92:1177–1191. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kofalvi A, et al. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:2874–2884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4232-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rodriguez JJ, Mackie K, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural localization of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor in mu-opioid receptor patches of the rat Caudate putamen nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:823–833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00823.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simon AC, et al. Activation-dependent plasticity of polarized GPCR distribution on the neuronal surface. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013;5:250–265. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjt014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pan X, Ikeda SR, Lewis DL. Rat brain cannabinoid receptor modulates N-type Ca2+channels in a neuronal expression system. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;49:707–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leterrier C, et al. Constitutive activation drives compartment-selective endocytosis and axonal targeting of type 1 cannabinoid receptors. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:3141–3153. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5437-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pickel VM, Chan J, Kearn CS, Mackie K. Targeting dopamine D2 and cannabinoid-1 (CB1) receptors in rat nucleus accumbens. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006;495:299–313. doi: 10.1002/cne.20881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fan N, Yang H, Zhang J, Chen C. Reduced expression of glutamate receptors and phosphorylation of CREB are responsible for in vivo Delta9-THC exposure-impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J. Neurochem. 2010;112:691–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seifert J, Ossege S, Emrich HM, Schneider U, Stuhrmann M. No association of CNR1 gene variations with susceptibility to schizophrenia. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;426:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Juhasz G, et al. CNR1 gene is associated with high neuroticism and low agreeableness and interacts with recent negative life events to predict current depressive symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2019–2027. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Domschke K, et al. Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) gene: impact on antidepressant treatment response and emotion processing in major depression. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.De MN, et al. Endocannabinoid signalling in the blood of patients with schizophrenia. Lipids Health Dis. 2003;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Giuffrida A, et al. Cerebrospinal anandamide levels are elevated in acute schizophrenia and are inversely correlated with psychotic symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:2108–2114. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leweke FM, Giuffrida A, Wurster U, Emrich HM, Piomelli D. Elevated endogenous cannabinoids in schizophrenia. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1665–1669. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199906030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hill MN, Miller GE, Ho WS, Gorzalka BB, Hillard CJ. Serum endocannabinoid content is altered in females with depressive disorders: a preliminary report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2008;41:48–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hill MN, Miller GE, Carrier EJ, Gorzalka BB, Hillard CJ. Circulating endocannabinoids and N-acyl ethanolamines are differentially regulated in major depression and following exposure to social stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1257–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nissen SE, et al. Effect of rimonabant on progression of atherosclerosis in patients with abdominal obesity and coronary artery disease: the STRADIVARIUS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1547–1560. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.13.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Christensen R, Kristensen PK, Bartels EM, Bliddal H, Astrup A. Efficacy and safety of the weight-loss drug rimonabant: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2007;370:1706–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Haller J, Varga B, Ledent C, Barna I, Freund TF. Context-dependent effects of CB1 cannabinoid gene disruption on anxiety-like and social behaviour in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;19:1906–1912. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martin M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Maldonado R, Valverde O. Involvement of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in emotional behaviour. Psychopharmacology. 2002;159:379–387. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pandey GN, Rizavi HS, Tripathi M, Ren X. Region-specific dysregulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and beta-catenin in the postmortem brains of subjects with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:160–171. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shelton RC, Hal MD, Lewis DA. Protein kinases A and C in post-mortem prefrontal cortex from persons with major depression and normal controls. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:1223–1232. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xing G, Chavko M, Zhang LX, Yang S, Post RM. Decreased calcium-dependent constitutive nitric oxide synthase (cNOS) activity in prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia and depression. Schizophr. Res. 2002;58:21–30. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Henson MA, et al. Developmental regulation of the NMDA receptor subunits, NR3A and NR1, in human prefrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2008;18:2560–2573. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karolewicz B, Stockmeier CA, Ordway GA. Elevated levels of the NR2C subunit of the NMDA receptor in the locus coeruleus in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1557–1567. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scarr E, Money TT, Pavey G, Neo J, Dean B. Mu opioid receptor availability in people with psychiatric disorders who died by suicide: a case control study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Uriguen L, et al. Immunodensity and mRNA expression of A2A adenosine, D2 dopamine, and CB1 cannabinoid receptors in postmortem frontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia: effect of antipsychotic treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2009;206:313–324. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.