Abstract

Background

BRCA2-associated breast and ovarian cancers are sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy. It is unknown whether BRCA2-associated prostate cancer responds favorably to such treatment.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of a single-institution cohort of men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer was performed to determine the association between carrier status of pathogenic BRCA2 germline variants and prostate-specific antigen response to carboplatin-based chemotherapy. From 2001-2015, 8,081 adult men with prostate cancer seen in consultation and/or treated at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute provided blood samples and consented to analysis of biological material and clinical records. A subgroup of 141 received at least two doses of carboplatin and docetaxel for castration-resistant disease (94% were also taxane refractory). These subjects were categorized according to absence or presence of pathogenic germline mutations in BRCA2, based on DNA sequencing from whole blood. Primary outcome was response rate to carboplatin/docetaxel chemotherapy as defined by decline in prostate-specific antigen exceeding 50% within 12 weeks of initiating this regimen. Association between BRCA2 mutation status and response to carboplatin-based chemotherapy was tested, using Fisher’s exact test, with a two-sided p-value of <0.05 as threshold for significance.

Results

Pathogenic germline BRCA2 variants were observed in 8/141 (5.7%; 95% CI=2.5%-10.9%) participants. Six of eight (75%) BRCA2 carriers experienced prostate-specific antigen decline >50% within 12 weeks, compared to 23 of 133 (17%) non-carriers (absolute difference 58%; 95% CI=27%-88%; P<0.001). Prostate cancer cell lines functionally corroborate these clinical findings.

Conclusions

BRCA2-associated castration-resistant prostate cancer is associated with higher likelihood of response to carboplatin-based chemotherapy than non-BRCA2 associated prostate cancer.

Keywords: prostate cancer, castration-resistance, DNA damage repair, BRCA2, carboplatin

INTRODUCTION

Breast and ovarian cancer families segregating deleterious BRCA2 variants have an increased risk of developing PCa1–4. Multiple studies – several based on cases ascertained through breast and ovarian cancer pedigrees, early age of onset, and/or Ashkenazi Jewish or Icelandic ancestry – have reported associations between BRCA2 variants and features of aggressive PCa, including higher grade, more advanced stage at diagnosis, and inferior overall survival4–10.

Emerging evidence suggests that status of the DNA damage repair pathway influences sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients with mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 create a defect in homologous DNA recombination, making cells harboring these mutations susceptible to DNA damaging agents such as cisplatin or carboplatin. BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast and ovarian cancers, for example, are more responsive to platinum-based chemotherapy than non-BRCA2 mutated cancers11, 12. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that PCa patients with DNA repair defects (in the germline or somatic genomes) would similarly have a higher response rate to platinum-based chemotherapy than non-carriers13–15.

However, platinum agents are not used routinely for treatment of PCa. While case series and early phase studies of platinum-based chemotherapy suggest activity in some metastatic castration-resistant PCa (mCRPC) patients14, 16, a phase III trial of one agent, satraplatin, failed to show survival benefit in a general mCRPC population17. As a result, platinum agents are not currently included in clinical practice guidelines, except for the rare small cell variant of PCa18.

In this study, we hypothesized that men with metastatic prostate cancer harboring protein-truncating germline variants in BRCA2 might respond more favorably to platinum-based chemotherapy compared to otherwise similar men lacking these variants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study cohorts

The Gelb Center cohort at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) has been described previously19. From 2001-2015, 8,081 men with PCa provided blood samples for DNA extraction and consented to analysis of blood specimens and medical records on DFCI IRB-approved protocol 01-045. We identified men who received at least two doses of carboplatin/docetaxel chemotherapy for mCRPC. Patients in the database who received only one cycle were excluded. Men with small cell and neuroendocrine histology (based on examination of primary prostate tissue in the majority of cases) were excluded. Docetaxel/carboplatin therapy had been tested at DFCI in a dual institution phase 2 study that accrued 34 subjects between 2004 and 200616. Fourteen taxane-refractory subjects from that trial were included in the present study, along with an additional 130 men who received the regimen but were not enrolled in a therapeutic clinical trial. In total, 144 subjects met inclusion criteria; all received at least two doses of carboplatin (AUC=3–5) in combination with docetaxel (60–75 mg/m2) every three weeks. All patients were castration-resistant and 133 men were taxane resistant at the time they initiated docetaxel/carboplatin. Three men (all non-carriers for BRCA2) were excluded because PSA levels were not adequately ascertained. Neither family history nor germline genetic testing was a selection criterion for use of this chemotherapy regimen.

Genetic sequencing/analysis

Using DNA isolated from blood samples, next-generation targeted sequencing was performed using the Illumina TruSight Cancer Sequencing Panel (http://www.illumina.com/products/trusight_cancer.html). The panel includes 94 genes (35 have been identified as being involved in human DNA repair20). Sequencing libraries were created according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Variant call pipeline

To identify genomic variants we used two independent commonly used standard variant calling pipelines (GATK21, 22 and samtools/bcftools23, 24). Basic statistics were performed, including read numbers (average 300,000) and alignment rates (83.41-89.78%).

Bowtie2 aligner was used and PCR duplicates were removed by samtools rmdup followed by variant calling using samtools mpileup (base quality>30) and bcftools call. Generated VCF files were converted and annotated by Annovar. High-quality Annovar scores (Q>200) were called and frameshift (insertion/deletion) and stop gain mutations were collected. All candidate BRCA2 variants were validated by Sanger sequencing.

Six distinct BRCA2 variants distributed across eight carriers met criteria (indel resulting in frameshift or nonsense mutation). All variants included in the analysis were scored as Pathogenic by the ClinVar database (accessed March 9, 2016)25 or guidelines set by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomic and the Association for Molecular Pathology26. Variants in the other 35 DNA damage repair genes were subjected to the same criteria for inclusion.

Responsiveness to Platinum Chemotherapy

Platinum responsiveness was evaluated by comparing the baseline PSA obtained at initiation of carboplatin/docetaxel therapy with the PSA measurement obtained 12 weeks (+/− 2 weeks) later.

Men who survived for 12 weeks and had a PSA decline exceeding 50% were categorized as responders. Men who died within 12 weeks of treatment initiation or whose PSA levels did not decline by 50% were categorized as non-responders. Twelve weeks was chosen to give subjects ample time to experience a significant response, while ensuring that variation in number of cycles did not confound the analysis. Investigators without knowledge of participants’ clinical characteristics or chemotherapy response performed the sequencing and determined BRCA2 status. Clinical investigators ascertained PSA response without knowledge of BRCA2 status.

Statistical methods

The prevalence of BRCA2 mutations was estimated with exact 95% confidence intervals. Clinical characteristics were compared by BRCA2 carrier status using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and t-tests or non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables. Overall survival was defined from date of initiation of carboplatin/docetaxel through date of death from any cause; patients who were not deceased were censored on the date they were last known to be alive. The association of BRCA2 mutation status with PSA response and overall survival were tested using Fisher’s exact test and log rank test. Adjusted odds ratios for the outcome of PSA response and hazard ratios for the outcome of overall survival were obtained, respectively, by logistic and Cox proportional hazards regression models controlling for age, pretreatment PSA (log-transformed), year of treatment, and presence of metastatic disease at initial diagnosis. The association of PSA response and overall survival was evaluated by the log rank test, limiting this analysis to 130 patients who survived to the landmark time of 12 weeks (i.e. the time at which PSA response was ascertained). A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp).

Functional analyses of BRCA2 mutations

PC-3 and LNCaP cells were obtained from ATCC, maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and seeded into 96-well plates (1×104 cells/well), followed by siRNA and plasmid transfection. BRCA2 or non-specific siRNA (final 40nM) was transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen), and wild-type BRCA2 or vector control (50ng/well) using X-tremeGENE HP reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two days after transfection, carboplatin or solvent were added, and cells were cultured for three days before AlarmaBlue assays (Invitrogen). The following siRNAs were used: control siRNA and siBRCA2-1 (Product # SIC001 and Product # NM_000059, ID:SASI_Hs01_00121792, Sigma Aldrich); siBRCA2-2 (AACAACAATTACGAACCAAAC, synthesized by Sigma Aldrich); pcDNA3-HA-BRCA2 (provided by Dr. David Livingston27). Western blot and RT-qPCR were performed as previously described28. Anti-BRCA2 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (SC-28235). The primers for RT-qPCR were: hBRCA1-F, TGTGAAGGCCCTTTCTTCTG; hBRCA1-R, TCCCATCTGTCTGGAGTTGA; hBRCA2-F, CAAATAGACGAAAGGGGCAA; hBRCA2-R, CCAGACTTTCAGCCATCTTG. All experiments were performed in three replicates and these sets of experiments were repeated at least three separate times.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the 141 men with mCRPC who were assessed for germline BRCA2 status are shown in Table 1. All subjects but eight (94%) have died of PCa. Of the 141 subjects, eight harbored a pathogenic germline BRCA2 variant (5.7%; 95% CI=2.5%-10.9%). Thirty-five other genes implicated in the DNA damage repair pathway were analyzed for deleterious germline variants20, but no individual gene other than BRCA2 was represented more than once across the cohort (Supplementary Table 1). Carriers of deleterious BRCA2 variants were diagnosed at a younger age and had lower PSA at diagnosis compared with non-carriers. Carriers also more frequently reported family histories of prostate, breast or ovarian cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who received carboplatin/docetaxel, overall and separately by BRCA2 carrier status.

| Total | BRCA2 carriers | BRCA2 non-carriers | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=141 | N=8 (5.7%) | N=133 (94.3%) | ||

| Age at diagnosis, median (range) | 59 (40-80) | 53 (40-62) | 60 (40-80) | 0.03 |

|

| ||||

| PSA at diagnosis in ng/ml, median (range) | 13 (1-4600) | 5 (4-166) | 14 (1-4600) | 0.10 |

|

| ||||

| Gleason score, n (%) | 0.81 | |||

| 6 | 9 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (6.8) | |

| 7 | 31 (22.0) | 1 (12.5) | 30 (22.6) | |

| 8–10 | 88 (62.4) | 6 (75.0) | 82 (61.7) | |

| Unknown | 13 (9.2) | 1 (12.5) | 12 (9.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Initial treatment, n (%) | 0.99 | |||

| Radical prostatectomy for localized disease | 57 (40.4) | 3 (37.5) | 54 (40.6) | |

| Radiation therapy for localized disease | 58 (41.1) | 4 (50.0) | 54 (40.6) | |

| Systemic treatment for metastases at diagnosis | 26 (18.4) | 1 (12.5) | 25 (18.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Known family history of prostate cancer, n (%) | 0.65 | |||

| Yes | 26 (18.4) | 2 (25.0) | 24 (18.0) | |

| No | 112 (79.4) | 6 (75.0) | 106 (79.7) | |

| Unknown | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Known family history of breast or ovarian cancer, n (%) | 0.01 | |||

| Yes | 18 (12.8) | 4 (50.0) | 14 (10.5) | |

| No | 118 (83.7) | 4 (50.0) | 114 (85.7) | |

| Unknown | 5 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Known family history of BRCA, n (%) | 0.009 | |||

| Yes | 3 (2.1) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| No | 135 (95.7) | 6 (75.0) | 129 (97.0) | |

| Unknown | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Ancestry, n (%) | 0.99 | |||

| European American | 123 (87.2) | 8 (100.0) | 115 (86.5) | |

| African American | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.0) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) | |

| Unknown | 12 (8.5) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (9.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Interval between date of diagnosis and carboplatin start in years, median (range) | 6.3 (0.5-20.7) | 4.5 (1.1-13.7) | 6.3 (0.5-20.7) | 0.52 |

|

| ||||

| Extent of metastatic disease at start of carboplatin, n (%) | 0.45 | |||

| Bone and/or lymph node only | 91 (64.5) | 4 (50.0) | 87 (65.4) | |

| Visceral metastases beyond bone/lymph nodes | 49 (34.8) | 4 (50.0) | 45 (33.8) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

|

| ||||

| PSA at start of carboplatin in ng/ml, median (range) | 170 (0-9145) | 49 (1-515) | 204 (0-9145) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| Progression on docetaxel prior to docetaxel/carboplatin | 133 (94.3) | 7 (87.5) | 126 (94.7) | 0.38 |

|

| ||||

| Duration of treatment in weeks, median (range) | 13 (3-114) | 15 (13-33) | 12 (3-114) | 0.26 |

| Number of cycles carboplatin received, median (range) | 4.5 (2-24) | 5 (4-15) | 4 (2-24) | 0.20 |

P values for differences in clinical characteristics by BRCA2 carrier status were determined using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables; the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test for PSA values, interval between diagnosis and carboplatin start date, duration of treatment, and number of cycles; and t-test for age at diagnosis. Patients with unknown values were excluded from statistical comparisons.

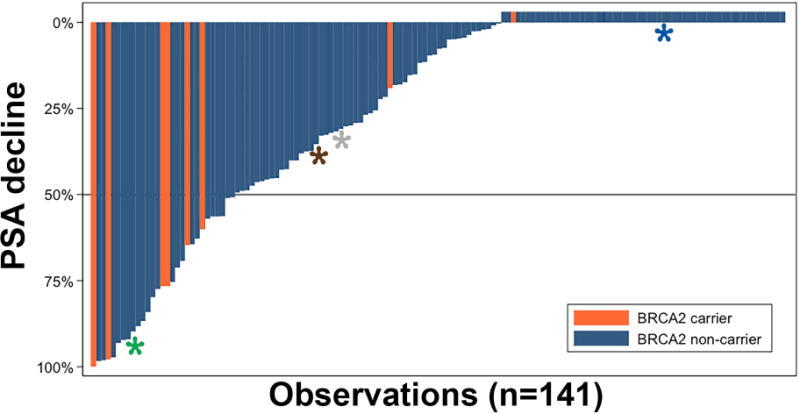

Figure 1 reveals the percent PSA decline for each subject from baseline to 12 weeks follow-up. Notably, among the eight BRCA2 carriers, six (75%) had a >50% decline in PSA within 12 weeks of treatment initiation, whereas 23 of the 133 men (17%) lacking a deleterious BRCA2 germline variant had a >50% decline (absolute difference=58%; 95% CI=27-88%, P<0.001). This association corresponded to an unadjusted odds ratio of 14.3 (95% CI=2.7-75.6). Adjusted for age, pretreatment PSA (log-transformed), year of treatment, and presence of metastatic disease at initial diagnosis, the adjusted odds ratio is 11.3 (95% CI=2.0-63.3, p=0.006). Among BRCA2 carriers, 2/8 (25%) experienced a 90% decline in PSA, compared with 6/133 (4.5%) in non-carriers. In terms of 30% PSA declines, responders comprised 6/8 (75%) of carriers and 43/133 (32.3%) of non-carriers.

Figure 1. PSA response to carboplatin/docetaxel chemotherapy among men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer.

Each column represents an individual subject. Treatment response was defined as >50% decline in PSA (below the gray horizontal line). Asterisks depict carriers of pathogenic germline variants in other DNA damage repair genes: blue, FANCA; grey, BLM; brown, ATM; green, MSH2.

For the entire group of 141 men, median survival from initiation of carboplatin/docetaxel was 10.2 months; among those who died, survival ranged from 1.54 to 98.1 months. In the landmark time analysis, PSA response >50% was associated with prolonged survival. Among 130 patients who survived > 12 weeks from initiation carboplatin/docetaxel, median survival was 16.4 months for those with PSA decline exceeding 50% and 9.4 months for those with no response or a decline of less than 50% (p=0.01 logrank, Supplementary Figure 1). Overall survival from treatment initiation was longer among carriers of pathogenic BRCA2 germline variants. Median survival from the start of chemotherapy was 18.9 months for carriers and 9.5 months for non-carriers (p=0.03 log-rank test, Supplementary Figure 2). This association corresponded to an unadjusted hazard ratio of 0.41 (95% CI=0.18-0.93) and an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.52 (95% CI=0.22-1.25, p=0.14).

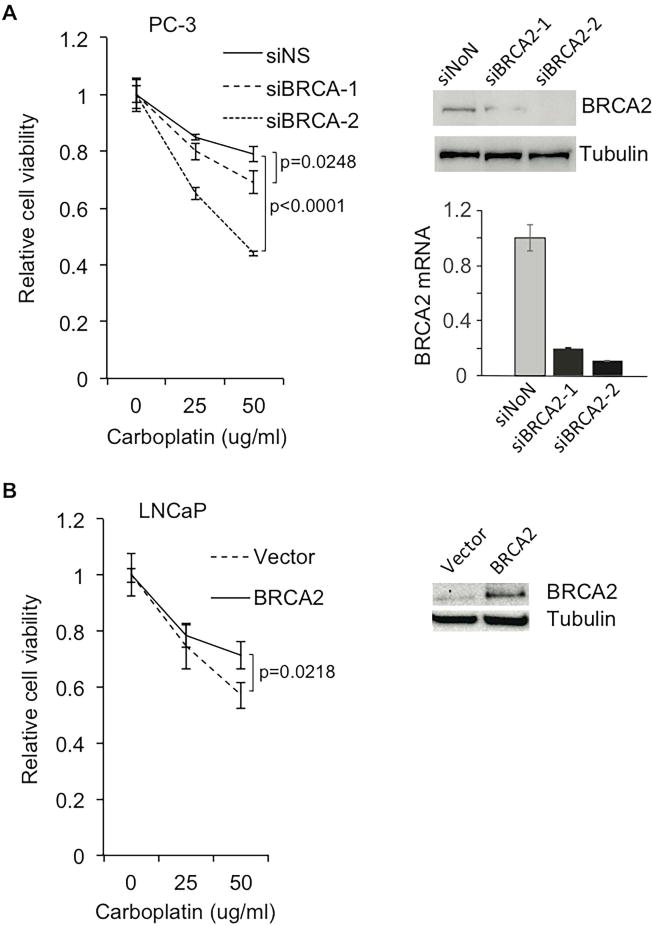

To functionally evaluate the role of BRCA2 in carboplatin sensitivity, PC-3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cell lines were analyzed. At baseline, PC-3 cells express wild-type BRCA2 at a high level, whereas LNCaP cells negligibly express BRCA2 (Supplementary Figure 3). Suppression of BRCA2 in PC-3 cells significantly reduced cell viability in the presence of carboplatin (Figure 2). Consistent with this, overexpression of BRCA2 in LNCaP cells enhanced cell viability under the same conditions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Alteration of BRCA2 expression in PCa cells affects their response to carboplatin treatment.

(A) Knockdown of BRCA2 in PC-3 cells increases carboplatin-induced cell death. BRCA2 siRNA knockdown efficiency was confirmed by Western blot and RT-qPCR. (B) Overexpression of BRCA2 in LNCaP cells protects cells from carboplatin treatment. Expression levels of BRCA2 in LNCaP cells were examined by Western blot.

DISCUSSION

We identified a cohort of 141 men with metastatic castration-resistant and docetaxel-resistant prostate cancer from case series unselected for family history, age or presence of germline mutations who received carboplatin/docetaxel chemotherapy. We found that the presence of pathogenic germline BRCA2 variants was associated with increased responsiveness to platinum-based-chemotherapy, based on PSA decline at 12 weeks.

Overall, 20% of men had a PSA declines >50% within 12 weeks of treatment initiation. This is slightly less than the 25.4% response rate observed in the treatment arm of the phase III trial of satraplatin, a platinum agent administered for mCRPC in the docetaxel-refractory setting17. It is considerably less than was observed in a phase III trial studying cabazitaxel, also in the docetaxel-refractory setting. In that trial, 39.2% of those who received cabazitaxel demonstrated a >50% PSA response29. However, in the present cohort, when focusing on the subset of patients carrying a pathogenic germline BRCA2 variant, 75% demonstrated a >50% PSA decline. This response rate is appreciably higher than observed in previous studies of men with docetaxel-refractory mCRPC, including the cabazitaxel trial. This relationship between genotype and responsiveness to platinum chemotherapy is consistent with the experience observed among BRCA2 carriers with breast and ovarian cancers30.

Although the results suggest a survival advantage for BRCA2-associated mCPRC treated with carboplatin/docetaxel, the size of this retrospective study does not allow us to definitively reach this conclusion. It is unclear whether the trend in improved survival stems from BRCA2’s role as a prognostic factor for mCRPC or from its role as a predictive factor corresponding to carboplatin responsiveness. Previous evidence showing that BRCA2 mutations are associated with more aggressive prostate cancer7, coupled with the superior PSA decline observed among BRCA2 carriers in this study, suggests the latter: BRCA2 status predicts a clinically meaningful response to carboplatin-based chemotherapy which in turn may be associated with improved outcomes compared with non-carriers.

Since our results suggest that BRCA2 inherited variants are a biomarker for platinum responsiveness, determination of BRCA2 status and personalizing treatment with carboplatin for mutation carriers could guide clinical decisions at key junctures in the course of PCa treatment. Settings in which clinical trials that test such precision treatment strategies – likely requiring multi-center collaborations – may be warranted. Future research could focus on several important clinical contexts: i) Localized high-grade PCa - Notably, seven of eight BRCA2 carriers in our mCRPC cohort were initially diagnosed with localized disease via PSA screening and were treated with curative intent, suggesting that there is an opportunity to alter clinical course in this population. For BRCA2 carriers, a regimen such as carboplatin/docetaxel may prove effective as neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment along with radiation and hormonal therapy. ii) Hormone-naïve metastatic PCa - Docetaxel has emerged as part of standard upfront management of newly diagnosed PCa metastases31. BRCA2 carriers presenting with metastases may benefit from the addition of carboplatin to androgen deprivation therapy and docetaxel. iii) Chemotherapy-naïve mCRPC - Though trials using platinum in CRPC have been equivocal, as described above16, 17, 32, platinum agents could be evaluated as part of first-line treatment for mCRPC for this subset of patients.

The study’s results should be viewed in the context of several key limitations. The size of the cohort – in particular, the carrier cohort – could lead to clinical imbalances, such as differences in median PSA (Table 1), that in turn influence response. Also, although men in the cohort were castration- and docetaxel-resistant, they varied in the amount of prior treatment received and the era in which they were treated (26 were started on carboplatin in 2010 or later, and four subjects received abiraterone or enzalutamide post-carboplatin). In addition, the point within the natural history of disease in which carboplatin/docetaxel therapy was initiated varied widely. Radiographic response to therapy could not be applied to the analysis, since many men had no imaging performed immediately proceeding or following treatment. Those who did undergo imaging had different modalities used to evaluate tumor burden (e.g., CT scan vs. bone scan) and had follow-up studies at inconsistent intervals. Among patients exhibiting a >50% PSA decline on docetaxel/carboplatin, two of six carriers and nine of 23 non-carriers underwent CT or bone scan during treatment. One carrier and five non-carriers demonstrated objective soft tissue responses.

Similar to carboplatin, poly(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition has demonstrated increased activity against the metastatic tumors of germline BRCA2 carriers13, 15. In a recent phase II study, PSA responses were consistently observed among BRCA2 carriers receiving PARP inhibitors – three of three germline carriers experienced PSA declines >50%13. PARP inhibitors may be an alternative for platinum chemotherapy and may have more favorable side effect profile13. However, the costs of sustained PARP inhibition are currently higher than the costs of 6 cycles of carboplatin. Our results strongly motivate future studies evaluating both carboplatin and PARP inhibitors or their use in combination for men with BRCA2-associated PCa.

In addition to inherited variation, there are acquired mutations at DNA damage repair pathway genes, most commonly within BRCA233. Individuals whose tumors have acquired somatic mutations in these genes may also respond favorably to platinum agents14. It is likely that several of the favorable responses observed among non-carriers in the present cohort had tumors with somatic mutations in DNA damage repair pathway genes. Also, though we excluded subjects who demonstrated neuroendocrine differentiation, histology was assessed using primary tumors in most cases. We presume that many cancers in the cohort underwent neuroendocrine differentiation by the time they were treated with carboplatin. This could influence response rates and confound the analysis. Efforts to obtain and interrogate metastatic tissue and/or circulating biomarkers in addition to germline testing should be prioritized and presumably would expand the number of carboplatin/PARP inhibitor candidates.

This study illustrates an important challenge in precision medicine – drawing inferences from necessarily small groups of patients. First, rates of deleterious germline variants in BRCA2 are relatively rare among PCa patients. In a previous series, exome sequencing of BRCA2 revealed mutations in only 1.4% of biopsy-detected PCa cases9. Second, opportunities to study men with prostate cancer treated with platinum are limited because this agent is rarely used. The only approved chemotherapy agents for metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate are taxanes and the anthracycline mitoxantrone. Platinum chemotherapy generally is not considered for mCRPC, except for men with small cell or neuroendocrine histologies, both of which were excluded from our study.

In summary, these data strongly motivate BRCA2 sequencing in men with high-grade prostate cancer in larger prospective studies in various clinical settings. More broadly, our results demonstrate the power of interrogating prior datasets with new technologies and ideas to rapidly actualize the goals of precision medicine.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival following initiation of carboplatin/docetaxel by PSA response at 12 weeks, among 130 patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and who survived for at least 12 weeks.

Supplementary Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival following initiation of carboplatin/docetaxel by BRCA2 carrier status, among 141 patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Supplementary Figure 3. RNA-seq data indicating BRCA2 mRNA levels in prostate cancer LNCaP and PC-3 cell lines.

Supplementary Table 1. The ten germline variants in DNA damage repair genes identified in 12 of 141 men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. David Livingston for the kindly providing the plasmid pcDNA3-HA-BRCA2.

Grant : P30 CA008748.

Funding: No funding sources or financial disclosures to report.

Footnotes

Author contributions:

Mark M. Pomerantz: conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, writing–initial draft and final revisions. Sandor Spisák: analysis and interpretation of data, writing–initial draft and final revisions. Li Jia: conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Angel M. Cronin: analysis and interpretation of data, writing–initial draft and final revisions. Istvan Csabai: analysis and interpretation of data. Elisa Ledet: acquisition of data. A. Oliver Sartor: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, approval of the final article. Irene Rainville: analysis and interpretation of data. Edward O’Connor: acquisition of data. Zachary T. Herbert: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Zoltan Szállási: analysis and interpretation of data, approval of the final article. William K. Oh: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, approval of the final article. Philip W. Kantoff: design of the study, writing–initial draft and final revisions, approval of the final article. Judy E. Garber: design of the study, writing–initial draft and final revisions, approval of the final article. Deborah Schrag: design of the study, writing–initial draft and final revisions, approval of the final article. Adam S. Kibel: conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, writing–initial draft and final revisions. Matthew L. Freedman: conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, writing–initial draft and final revisions.

Conflicts of Interest: None

Contributor Information

Mark M. Pomerantz, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA.

Sandor Spisák, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA.

Li Jia, Department of Surgery, Division of Urology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA

Angel M. Cronin, Division of Population Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA

Istvan Csabai, Department of Physics of Complex Systems Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Elisa Ledet, Department of Medicine, Tulane Cancer Center, New Orleans, USA

A. Oliver Sartor, Department of Medicine, Tulane Cancer Center, New Orleans, USA

Irene Rainville, Division of Population Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA

Edward O’Connor, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA

Zachary T. Herbert, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA

Zoltan Szállási, Department of Pediatrics, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, USA

William K. Oh, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Tisch Cancer Institute, New York, USA

Philip W. Kantoff, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute, New York, USA

Judy E. Garber, Division of Population Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA

Deborah Schrag, Division of Population Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA

Adam S. Kibel, Department of Surgery, Division of Urology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA

Matthew L. Freedman, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA

References

- 1.Breast Cancer Linkage C. Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1310–1316. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.15.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Asperen CJ, Brohet RM, Meijers-Heijboer EJ, et al. Cancer risks in BRCA2 families: estimates for sites other than breast and ovary. J Med Genet. 2005;42:711–719. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kote-Jarai Z, Leongamornlert D, Saunders E, et al. BRCA2 is a moderate penetrance gene contributing to young-onset prostate cancer: implications for genetic testing in prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1230–1234. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher DJ, Gaudet MM, Pal P, et al. Germline BRCA mutations denote a clinicopathologic subset of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2115–2121. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tryggvadottir L, Vidarsdottir L, Thorgeirsson T, et al. Prostate cancer progression and survival in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:929–935. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards SM, Evans DG, Hope Q, et al. Prostate cancer in BRCA2 germline mutation carriers is associated with poorer prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:918–924. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro E, Goh C, Leongamornlert D, et al. Effect of BRCA Mutations on Metastatic Relapse and Cause-specific Survival After Radical Treatment for Localised Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bancroft EK, Page EC, Castro E, et al. Targeted prostate cancer screening in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the initial screening round of the IMPACT study. Eur Urol. 2014;66:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akbari MR, Wallis CJ, Toi A, et al. The impact of a BRCA2 mutation on mortality from screen-detected prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1238–1240. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, et al. Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, et al. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2654–2663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chetrit A, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, Ben-David Y, Lubin F, Friedman E, Sadetzki S. Effect of BRCA1/2 mutations on long-term survival of patients with invasive ovarian cancer: the national Israeli study of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:20–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.6905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1697–1708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng HH, Pritchard CC, Boyd T, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Biallelic Inactivation of BRCA2 in Platinum-sensitive Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:244–250. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross RW, Beer TM, Jacobus S, et al. A phase 2 study of carboplatin plus docetaxel in men with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer who are refractory to docetaxel. Cancer. 2008;112:521–526. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sternberg CN, Petrylak DP, Sartor O, et al. Multinational, double-blind, phase III study of prednisone and either satraplatin or placebo in patients with castrate-refractory prostate cancer progressing after prior chemotherapy: the SPARC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5431–5438. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohler JL, Armstrong AJ, Bahnson RR, et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 1.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:19–30. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh WK, Hayes J, Evan C, et al. Development of an integrated prostate cancer research information system. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2006;5:61–66. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2006.n.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood RD, Mitchell M, Lindahl T. Human DNA repair genes, 2005. Mutat Res. 2005;577:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2987–2993. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D862–868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Silver DP, Walpita D, et al. Stable interaction between the products of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes in mitotic and meiotic cells. Mol Cell. 1998;2:317–328. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Decker KF, Zheng D, He Y, Bowman T, Edwards JR, Jia L. Persistent androgen receptor-mediated transcription in castration-resistant prostate cancer under androgen-deprived conditions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10765–10779. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. The DNA damage response and cancer therapy. Nature. 2012;481:287–294. doi: 10.1038/nature10760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, et al. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:737–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Regan MM, O’Donnell EK, Kelly WK, et al. Efficacy of carboplatin-taxane combinations in the management of castration-resistant prostate cancer: a pooled analysis of seven prospective clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:312–318. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival following initiation of carboplatin/docetaxel by PSA response at 12 weeks, among 130 patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and who survived for at least 12 weeks.

Supplementary Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival following initiation of carboplatin/docetaxel by BRCA2 carrier status, among 141 patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Supplementary Figure 3. RNA-seq data indicating BRCA2 mRNA levels in prostate cancer LNCaP and PC-3 cell lines.

Supplementary Table 1. The ten germline variants in DNA damage repair genes identified in 12 of 141 men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.