Abstract

Evidence-based suggestions for developing an effective clinician-client relationship built upon trust and honesty will be shared, as well as a review of relevant scope of practice issues for audiologists. Audiologists need to be prepared if a patient threatens self-harm. Many patients do not spontaneously report their suicidal thoughts and intentions to their care providers, so we need to be alert to warning signs. Information about the strongest predictors of suicide, how to ask about suicidal intentions, and how to assess the risk of suicide will be presented. Although it is our responsibility to recognize suicidal tendencies and have a plan for preventive intervention, it is not our responsibility to conduct a suicide evaluation. Tips for collecting critical information to be provided to qualified professionals will be shared, as well as additional information about how and to whom to disclose this information. A list of suicide warning signs will be reviewed as well as some additional suggestions for how to react when a patient discloses his or her suicidal intent. A review of available resources (for both the patient and the clinician) will be provided, along with instructions for how and when it is appropriate to access them.

Keywords: Suicide, self-harm, risk signs, crisis resources

Learning Outcomes: As a result of this activity, the participant will be able to (1) identify risk factors and warning signs for suicidal behavior and use that information to formulate a plan for how to react when patients disclose suicidal intent and (2) access resources that can help both themselves (the providers) and their patients.

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention estimates that suicide is the 10th leading cause of death (44,193 Americans) in the United States each year. This issue is estimated to cost our country $51 billion annually. 1 As such, suicide is a topic that should be discussed and addressed openly in all health care settings. There are risk factors (discussed later) that all clinicians should be aware of, regardless of the population being treated or the field of specialty. Even clinicians who think that they may not need to think about suicide (for example, those who work primarily with patients under the age of 21) may be surprised to find that each population has its own risk factors and concerns related to suicide. For instance, it has been reported that suicide represents 12% of deaths each year in the 15- to 19-year-old age cohort in the United States and that it is the third leading cause of mortality in this age group behind accidental injury and homicide. 2 Even clinicians who may feel that their field of specialty does not inherently carry a high risk for suicidal patients (e.g., audiology) may be surprised to find how relevant suicide intervention skills can be in their practice.

Developing Counseling Skills to Create A Trusting Relationship with Your Patients

Despite primarily identifying as a specific type of clinician (e.g., audiologist, speech-language pathologist), all practicing clinicians function as a counselor in at least some capacity throughout the time that they interact with patients. As such, clinicians must consider factors that facilitate a patient's trust and willingness to risk disclosing suicidal ideation. Several factors have been identified and include the provider being genuine and empathic, using understandable language, and building a personal relationship. 3 It has also been suggested that therapist behavior is among the predictors of disclosure of suicidal ideation and that clinicians should focus on developing a strong working alliance with their patients to promote this behavior. 4 Additionally, specific words and phrasing to avoid (e.g., asking outright if patients are suicidal without creating a context first, no-problems-expected phrasing such as “You're not feeling suicidal, are you?”) have been identified because they may inhibit disclosure of information. 5

Previous research has linked higher levels of patient-physician trust to better outcomes, 6 but data specific to audiology are limited. Audiologists can use the Audiology Counselor Growth Checklist to foster positive interactions with their patients. 7 This checklist focuses on five specific areas of clinical interaction and can be used to promote the development of counseling skills in both audiologists and audiology students.

Additionally, audiologists should focus on differentiating between a content message and an affective message, which would allow the audiologist to appropriately respond in a way that lets the patient know that his or her primary message is being heard. 8 For example, if a patient asks, “Why is my tinnitus so annoying?,” he or she is likely not looking for an informational response, which would be something like, “I believe your tinnitus is annoying because of the heightened connections between your auditory, limbic, and autonomic nervous system.” Instead, this patient is trying to express an emotion (frustration, anger, etc.). In this case, a more appropriate response might be something that acknowledges that emotion, such as, “I can tell that this is really bothersome. It clearly has a big impact on your life and is very disruptive. What's the major reason that your tinnitus is such a problem for you?” This ability to distinguish between an informational message and an affective message is important because patients have reported that they feel that audiologists do not understand the difficulties that they are trying to express. 9 These difficulties often stem from and include emotions such as loneliness, isolation, dependence, frustration, depression, anxiety, anger, embarrassment, frustration, and guilt. 10

Comorbid Mental Health Issues

Audiologists should be especially aware of these risk factors because many conditions and disorders common to our practice have been associated with comorbid mental health issues that can become compounding risk factors. Hearing loss is a known risk factor for increased depression, 11 and it has been demonstrated that higher levels of distress (e.g., anxiety, depression, phobic anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility) have been noted in a hearing-impaired group when compared with a control group. 12 Tinnitus, hyperacusis, and misophonia have also been linked to high levels of anxiety and depression. 13 14 15 The overlap between dizziness and anxiety has been explored, 16 and there is evidence that several psychiatric conditions have been linked to chronic dizziness. 17 It has been noted that although the two diagnoses cannot be used interchangeably, children with auditory processing disorder and children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder display many similar symptoms, 18 and there is evidence to correlate auditory processing disorder and other mental health disorders. 19

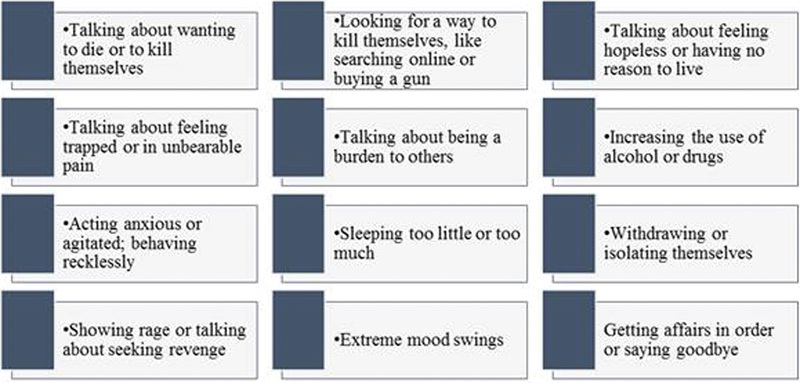

Risk Factors for Suicide

In the literature, several risk factors for suicide have been identified. Risk factors are characteristics that make it more likely that someone will consider, attempt, or die by suicide. These risk factors vary and are largely dependent on the specific population being studied. As an example, for those with clinical depression, these risk factors include male sex, family history of psychiatric disorder, previous attempted suicide, severe depression, hopelessness, comorbid disorders including anxiety, and misuse of alcohol and drugs. 20 For current and former U.S. military personnel, factors significantly associated with increased risk of suicide included male sex, depression, manic-depressive disorder, heavy or binge drinking, and alcohol-related problems. 21 Population-dependent variations excluded, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline has identified general risk factors to be aware of while interacting with patients or other people (see Fig. 1 ). 22

Figure 1.

Risk factors for suicide.

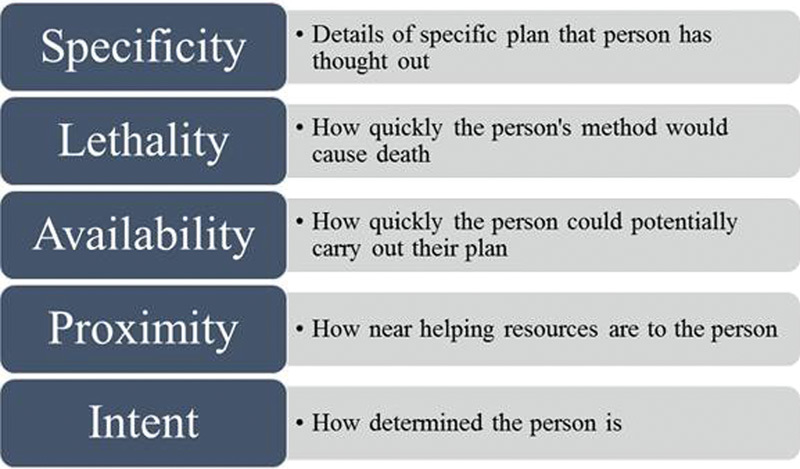

Importance of Recognizing Suicidal Tendencies

Audiologists cannot rely on patients to spontaneously express their intent of self-harm. The literature has demonstrated varying percentages of patients who express this intent to their care providers. 23 24 25 For this reason, clinicians need to be prepared if patients display warning signs indicating that they may harm themselves or engage in suicidal behavior. These warning signs should be considered an “invitation” to ask about suicidal intent (see Fig. 2 ). 20 26 Clinicians who are not experienced in dealing with patients at risk for suicide sometimes worry that asking about suicidal intentions may lead to suicidal thoughts in patients. However, there is no evidence to support this concern. The available evidence suggests that suicidal patients prefer more regular inquiry about their psychiatric symptoms and that these patients want to talk to their providers about their mental health issues. 27 If the patient expresses the intention to die, has a plan to commit suicide, and has lethal means available, the risk of suicide is considered imminent and action should be taken immediately. 28

Figure 2.

Warning signs for suicide.

Although audiologists need to be able to recognize suicidal tendencies and have a plan for intervention when required, it is not our responsibility to conduct suicide evaluations. These assessments are done by trained clinicians who can assess the level of danger and determine what action or actions would be appropriate. 29 It is more appropriate for audiologists and other clinicians who do not have this level of training to consider themselves mandatory reporters for self-harm just as they would be for suspected cases of child or elder abuse. Accordingly, audiologists should disclose suicidal ideation to a qualified professional (e.g., mental health professional, primary care physician). If risk signs exist or a patient reports suicidal thoughts, this information should be disclosed regardless of whether the audiologist thinks the patient may actually be at risk. 30 In cases where the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act applies, health care providers are permitted to disclose protected health information about a patient to law enforcement, family members, or others if the provider believes that the patient presents a serious danger to him- or herself or to others. 31 It may be advisable to inform patients of your intention to break confidentiality to ensure their safety. In this case, saying something like, “Mr. Patient, to ensure your safety, I feel it is necessary to share this information with your doctor. Your doctor will be able to take the appropriate steps to make sure you do not harm yourself.” If the patient protests your disclosure of this information, it is recommended to apologize while still maintaining that your primary concern and responsibility is his or her safety. 29

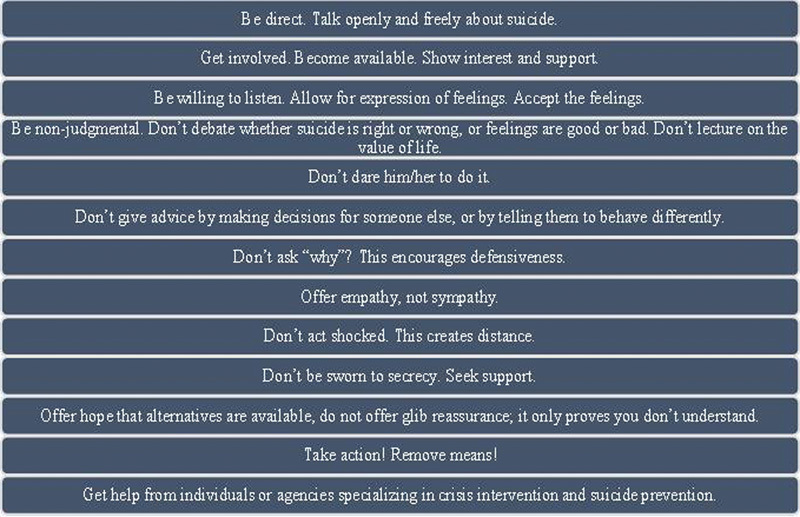

Formulating A Plan to React to Signs of Self-Harm

Once it has been determined that the patient is at risk, the next step should be to ask the patient about his or her intentions. 29 It is recommended that the patient be asked directly about suicidal thoughts, specifically using the word suicide , because this allows for clarification on the part of both the patient and the provider. This question can be as simple as “Are you having thoughts of suicide?” 32 If the answer to this question is yes, follow-up questions such as, “Could you tell me more about your thoughts?” or “Do you have a plan for how you would kill yourself?” should be asked to get more specific information. Any information that can be collected by the audiologist can then be passed along to a professional who is qualified to help the patient through this period of crisis. When listening to the patient's answers to these questions, there are five areas that should be paid specific attention, because they can provide more detailed information about the patient's level of risk: specificity, lethality, availability, proximity, intent (see Fig. 3 ). 29

Figure 3.

Five topics to listen for when asking about suicidal intent.

When dealing with someone who is threatening suicide or displaying warning signs, there are several tips to keep in mind to facilitate an honest conversation that will result in the most truthful and helpful information being disclosed. 33 See Fig. 4 for a discussion of these tips. If, as the clinician or caregiver, you are unsure what to do next, several crisis resources are available that can provide further guidance.

Figure 4.

Tips for dealing with someone who is threatening suicide or displaying warning signs.

Crisis Resources for Patient Safety

These crisis resources are available for both patients and providers. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is a resource that can be used both by someone in distress and anyone who is unsure how to help someone or if action should be taken. This resource provides free and confidential emotional support to people in crisis or distress 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The phone number to call is 1-800-273-TALK (8255). When this number is called, a trained person with a background in crisis counseling and suicide prevention will answer. Callers may be asked their first name, but do not need to provide more information if they do not want to. In any case, counselors are there to listen, support, and understand. Their goals are to help their callers stay safe, think through their situations, explore their options, and figure out how to proceed safely. 34

Resources to help someone else who is not available to sit and talk on the phone also exist. For instance, these resources are available on online platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter). In each case, social media safety teams can reach out to connect users with the help that they need. 35 Similarly, if the person in danger has hearing loss or difficulty speaking, he or she can still be helped by using an online chat with a LifeLine counselor or the TTY number (1-800-799-4889). 36 Veterans, service members, or anyone concerned about either can contact a dedicated Veterans' Crisis Line by calling the crisis hotline number and selecting the veterans option, texting, or using the online chat. 37

Local services that provide around-the-clock mental health crisis intervention and stabilization also exist in certain areas. One example is Allegheny County's re:solve Crisis Network, which is sponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This service can be contacted via telephone at 1-888-7-YOU-CAN or 1-888-796-8226. re:solve provides mobile, walk-in, and residential services in addition to phone services. 38

For patients who are determined to be in immediate danger and have been deemed unsafe to be left alone, emergency medical services may be used as a resource for transportation to the nearest emergency department. If the patient is cooperative and willing, he or she may be transported to the nearest emergency department or crisis center by another provider, friend, or family member. 39

Crisis Resources for Providers Experiencing Death of A Patient by Suicide

As a provider whose patient has committed suicide, it is common to experience distress. In fact, a range of emotions can be expected. This range includes shock, disbelief, grief, self-doubt, anger, shame, frustration, and relief among a variety of other commonly experienced feelings. 40 41 It is important to address the emotional issues experienced by a provider in this difficult time. Several recommendations have been made in this case and include addressing the need for social support, taking advantage of resources that are available, seeking psychotherapy if it is indicated, and receiving support from clinical supervisors and administrators. 42 Additionally, the American Association of Suicidology has a Web site for “clinician survivors” that provides resources and readings on the topic that many have found helpful. 43

Responsibility of Audiology Teaching Programs

Many teaching programs in audiology do not offer any formal training in crisis management. Moving forward, training programs may consider their responsibilities to their students in this area. Two main responsibilities have been identified: (1) taking all reasonable steps to prevent patient suicides from occurring in the form of thorough suicide intervention and assessment and (2) attending to the needs of the trainee in the event that patient suicide does occur. 44

In psychiatry programs, the prevalence of the experience of death of a patient by suicide among residents in this specialty ranged from 31% to 69%. However, data on this prevalence among medical students or residents in specialties other than psychiatry were nonexistent as of 2014. Ultimately, we do not know how often this happens, and there is a great need to develop research on this topic for learners who are outside of psychiatry. 45 It is possible that psychiatry programs may be partners moving forward in gathering data that could inform curriculum development for other programs.

Conclusions

Suicide is a stigmatized issue that many people (health care professionals included) do not feel comfortable addressing matter-of-factly with others. Education about suicide, awareness of risk factors and warning signs, and recommendations for intervention should be prevalent in all areas related to health care. All providers should consider themselves to be part of the suicide prevention community. Looking to the future, it is reasonable to expect that all professional programs should consider integrating suicide training and crisis intervention training into their curricula as anyone can become a person who is at risk.

References

- 1.American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Suicide. 2017. Available at:afsp.org/about-suicide/suicide-statistics/. Accessed August 10, 2017

- 2.Sneha J, Prakash C, Vinay S. Unexpected death or suicide by a child or adolescent: improving responses and preparedness of child and adolescent psychiatry trainees. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(11):15–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganzini L, Denneson L M, Press N et al. Trust is the basis for effective suicide risk screening and assessment in veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(09):1215–1221. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2412-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orf R. Keene, NH: Antioch University New England; 2014. Factors that promote and inhibit client disclosure of suicidal ideation [doctoral dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vannoy S D, Fancher T, Meltvedt C, Unützer J, Duberstein P, Kravitz R L. Suicide inquiry in primary care: creating context, inquiring, and following up. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(01):33–39. doi: 10.1370/afm.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safran D G, Taira D A, Rogers W H, Kosinski M, Ware J E, Tarlov A R. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(03):213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark J G. The audiology counseling growth checklist for student supervision. Semin Hear. 2006;27(02):116–126. [Google Scholar]

- 8.English K, Mendel L L, Rojeski T, Hornak J. Counseling in audiology, or learning to listen: pre- and post-measures from an audiology counseling course. Am J Audiol. 1999;8(01):34–39. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(1999/007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin F N, Krall L, O'Neal J. The diagnosis of acquired hearing loss. Patient reactions. ASHA. 1989;31(11):47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciorba A, Bianchini C, Pelucchi S, Pastore A. The impact of hearing loss on the quality of life of elderly adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:159–163. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S26059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang C Q, Dong B R, Lu Z C, Yue J R, Liu Q X. Chronic diseases and risk for depression in old age: a meta-analysis of published literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9(02):131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monzani D, Galeazzi G M, Genovese E, Marrara A, Martini A. Psychological profile and social behaviour of working adults with mild or moderate hearing loss. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28(02):61–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinto P CL, Marcelos C M, Mezzasalma M A, Osterne F JV, de Melo Tavares de Lima M A, Nardi A E. Tinnitus and its association with psychiatric disorders: systematic review. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128(08):660–664. doi: 10.1017/S0022215114001030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jüris L, Andersson G, Larsen H C, Ekselius L. Psychiatric comorbidity and personality traits in patients with hyperacusis. Int J Audiol. 2013;52(04):230–235. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2012.743043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schröder A, Vulink N, Denys D. Misophonia: diagnostic criteria for a new psychiatric disorder. PLoS One. 2013;8(01):e54706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furman J M, Jacob R G.A clinical taxonomy of dizziness and anxiety in the otoneurological setting J Anxiety Disord 200115(1-2):9–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staab J P. Chronic dizziness: the interface between psychiatry and neuro-otology. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19(01):41–48. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000198102.95294.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riccio C A, Hynd G W, Cohen M J, Hall J, Molt L. Comorbidity of central auditory processing disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(06):849–857. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iliadou V, Iakovides S. Contribution of psychoacoustics and neuroaudiology in revealing correlation of mental disorders with central auditory processing disorders. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;2(01):5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2832-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawton K, Casañas I Comabella C, Haw C, Saunders K.Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review J Affect Disord 2013147(1–3):17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeardMann C A, Powell T M, Smith T C et al. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former US military personnel. JAMA. 2013;310(05):496–506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.65164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.We can all prevent suicideAvailable at:suicidepreventionlifeline.org/how-we-can-all-prevent-suicide/. Accessed August 10, 2017

- 23.Cukrowicz K C, Duberstein P R, Vannoy S D, Lin E H, Unützer J. What factors determine disclosure of suicide ideation in adults 60 and older to a treatment provider? Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(03):331–337. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Husky M M, Zablith I, Alvarez Fernandez V, Kovess-Masfety V. Factors associated with suicidal ideation disclosure: results from a large population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2016;205:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews K, Milne S, Ashcroft G W. Role of doctors in the prevention of suicide: the final consultation. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44(385):345–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dazzi T, Gribble R, Wessely S, Fear N T. Does asking about suicide and related behaviours induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychol Med. 2014;44(16):3361–3363. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudd M D, Berman A L, Joiner T E, Jr et al. Warning signs for suicide: theory, research, and clinical applications. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006;36(03):255–262. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirschfeld R M, Russell J M. Assessment and treatment of suicidal patients. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(13):910–915. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suicide Prevention Resource Center.Suicide Screening and Assessment Waltham, MA: Education Development Center, Inc.2014 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flasher L, Fogle P. Nelson Education; 2011. Counseling Skills for Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists. [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.520-Does HIPAA permit a provider to disclose PHI about a patient if the patient presents a serious danger to self or othersAvailable at:www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/520/does-hipaa-permit-a-health-care-provider-to-disclose-information-if-the-patient-is-a-danger/index.html. Accessed August 14, 2017

- 32.Ottawa Suicide Prevention Coalition.Suicide: association for suicide preventionAvailable at:www.ottawasuicideprevention.com/suicide-first-aid-guidelines.html. Accessed August 14, 2017

- 33.Crisis Call Center.Suicide prevention—crisis call center2017. Available at:crisiscallcenter.org/suicide-prevention/. Accessed August 14, 2017

- 34.National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Home. Available at:suicidepreventionlifeline.org/. Accessed August 14, 2017

- 35.National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.Help someone elseAvailable at:suicidepreventionlifeline.org/help-someone-else/. Accessed August 14, 2017

- 36.National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.Deaf, hard of hearingAvailable at:suicidepreventionlifeline.org/help-yourself/for-deaf-hard-of-hearing/. Accessed August 14, 2017

- 37.National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Veterans. Available at:suicidepreventionlifeline.org/help-yourself/veterans/. Accessed August 14, 2017

- 38.UPMC.Re:Solve Crisis ServicesAvailable at:www.upmc.com/Services/behavioral-health/Pages/resolve-crisis-network.aspx. Accessed August 17, 2017

- 39.Carrigan C G, Lynch D J. Managing suicide attempts: guidelines for the primary care physician. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;5(04):169–174. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v05n0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendin H, Haas A P, Maltsberger J T, Szanto K, Rabinowicz H. Factors contributing to therapists' distress after the suicide of a patient. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(08):1442–1446. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger J T, Haas A P, Wynecoop S. Therapists' reactions to patients' suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):2022–2027. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellis T E, Patel A B. Client suicide: what now? Cognit Behav Pract. 2012;19(02):277–287. [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Association of Suicidology.Clinician Survivors2017. Available at:www.suicidology.org/suicide-survivors/clinician-survivors. Accessed August 17, 2017

- 44.Ellis T E, Dickey T O. Procedures surrounding the suicide of a trainee's patient: a national survey of psychology internships and psychiatry residency programs. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1998;29(05):492. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puttagunta R, Lomax M E, McGuinness J E, Coverdale J. What is the prevalence of the experience of death of a patient by suicide among medical students and residents? A systematic review. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(05):538–541. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]