Abstract

Audiologists are an integral part of the management of those with dizziness and vestibular disorders. However, little research has been performed on counseling approaches for patients who present with dizziness as a primary concern. Accordingly, it is important that audiology students are provided with didactic and experiential learning opportunities for the assessment, diagnosis, and management of this population. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is the most common vestibular disorder among adults. Doctor of Audiology students, at a minimum, should be provided with learning opportunities for counseling patients with this particular disorder. Implementation of patient-centered counseling is applied across various parts of the patient encounter from initial intake to treatment and patient education. The purpose of this article is to present the available evidence and to apply widely accepted theories and techniques to counseling those with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Didactic resources and experiential learning activities are provided for use in coursework or as a supplement to clinical education.

Keywords: Audiology, counseling, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, teaching, education

Learning Outcomes: As a result of this activity, the participant will be able to (1) apply widely accepted audiologic counseling concepts to the assessment and management of those with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and (2) identify appropriate didactic resources for facilitating learning and implementation of evidence-based, patient-centric counseling strategies when encountering those with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

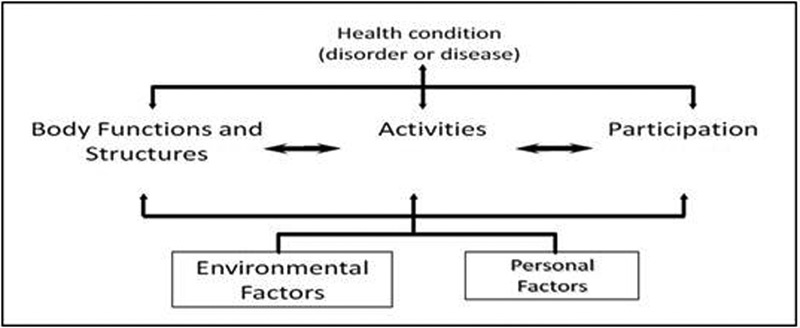

Research related to counseling in audiology has focused on the use of hearing technology, 1 patients with tinnitus, 2 3 and parents of children with hearing loss. 4 With the exception of fall risk, 5 surprisingly little attention has focused on audiologic counseling for the assessment and treatment of prevalent balance disorders. Similar to other areas of audiologic counseling, most, if not all, of the same concepts apply to counseling those with vestibular disorders. As with counseling those with hearing loss, there are two major aspects to counseling patients with dizziness: (1) patient education or informational counseling and (2) personal adjustment counseling. 6 In patient-centered counseling, the perspective of the clinician about signs and symptoms of the disorder melds with the patient's experience and interpretation of their condition. It is through these exchanges that a third space of mutual understanding is created, serving as the basis for a trusting, therapeutic relationship between the clinician and the patient. 7 However, the patient's disorder also needs to be examined within a specific social context. With the advent of the World Health Organization International Classification of Function's (WHO-ICF) paradigm of disability, patient-centered counseling also has come to include a biopsychosocial model, which includes the assessment of activity limitations, and participation restrictions that occur secondary to the disorder ( Fig. 1 ). 8

Figure 1.

World Health Organization, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Model.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) constitutes between 17 and 42% of all vertigo diagnoses. 9 It is also the most common vestibular disorder, occurring among both adults and children, but is more common at advanced ages. 9 10 Patients with untreated BPPV can experience increased risk for falls, decreased activities of daily living, increased depression, 11 as well as decreased quality of life due to a combination of all of these factors. 12 In addition to peripheral vestibular issues, patients over 65 years of age frequently have comorbidities that increase their risk for falls (e.g., arthritis, neuropathy, postural hypotension, vision impairment, etc.). These patients may need additional informational and personal adjustment counseling at various points during assessment and management for BPPV.

Recently updated practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of BPPV included recommendations for counseling these patients. 9 Doctor of Audiology students need increased didactic and experiential learning opportunities for audiologic counseling. 1 The authors have determined that focused instruction on knowledge and skills for counseling those with BPPV would be most useful because of the prevalence, acute presentation, and the centrality of the audiologist in patient care from intake to discharge. The journey of the patient with BPPV has four stages including: (1) intake/case history, (2) examination, (3) diagnosis and treatment approach, and (4) patient education. Each stage has its own counseling needs to address, requiring specific knowledge and skills. The purpose of this article is to provide a process-driven approach to teaching knowledge and skills complete with didactic resources for facilitating student learning and implementation of patient-centric counseling strategies across these four stages of the patient journey with audiologists ( Fig. 2 ).

Figure 2.

Framework for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo patient encounter.

Intake/Case History

Let's sit down and talk more about this dizziness you've been experiencing …

How does building a patient-centric relationship with a person with BPPV differ from or resemble that of someone with hearing loss? Are his or her counseling needs different? Is his or her patient journey different? These are all questions that may run through the minds of those who serve or teach students to work with patients with BPPV. However, it is clear that establishment of a patient-centered therapeutic relationship is paramount during the first stage of intake/case history. This is in addition to the other goals of gathering information leading towards differential diagnosis, which includes learning about the subjective and functional impacts of BPPV, and identification of any patient factors that may impact the assessment, diagnosis, or management of this disorder. Preliminary intake for these patients should focus on the nature of their dizzy sensations, time course of attacks, other associated symptoms, and pertinent medical history and are necessary for accurate diagnosis. 13 In addition, other comorbidities may alter the management and prognosis of BPPV for certain at-risk populations. 9 11 The clinical intake provides the necessary data for the diagnosis of BPPV and lays the foundation for establishing trust in a patient-centered relationship.

Table 1 shows counseling goals, techniques, and tools for intake and case history. First, it is essential that audiologists schedule sufficient time for the appointment. Clinicians need to display focused, empathetic concern toward the patient with congruence in their verbal and nonverbal communication, as outlined in the Person-Centered Counseling Theory. 14 For example, audiologists may appear to be disingenuous if their verbal communication displays interest in what patients have to say but is accompanied by hurried behaviors of looking at their watches or the tapping of toes. Moreover, it is essential to use a conversational style in asking patients open-ended questions about how they experience their dizziness and structure the intake allowing patients to ask questions and describe their experiences.

Table 1. Intake/Case History.

| Goals | Tools | Counseling Skills |

|---|---|---|

| • Conducting a patient-centric interview that allows for trust building in a therapeutic relationship • Identifying the problem and patient perception of the problem informally through case history and formally through subjective measures such as the Dizziness Handicap Inventory 18 • Identifying other patient-specific factors for which assessment or management approach might be modified (e.g., falls history, comorbid medical conditions, transportation to follow-up appointments, etc.) |

• Dizziness-related quality of life measures to measure personal impact to diagnosis and treatment options • Screening to identify any secondary psychological issues (if needed) • Exercise ( Appendix 1 ) |

• Focused, empathetic concern • Congruence between verbal and nonverbal information • Conversational-style intake • Open-ended questions • Three-layered listening to identify: o Description of the problem o Informational needs o Counseling needs identified from affective statements (e.g., anxiety, fears, irrational beliefs) • Minimal encouragers and reflective listening • Rational emotive counseling to defuse irrational fears or beliefs |

Listening is the most important counseling skill during the patient intake/case history stage and has at least three layers. For example, the first layer of listening is to patients' descriptions of their vestibular problems and carefully querying them for clarifications that aid in the diagnosis of BPPV. A second layer of listening is for patients' informational needs such as how the vestibular system works or what causes the room to seem like it is spinning, and so on. The third layer of listening is with the third ear or for patients' affective statements that may indicate feelings about their condition warranting further exploration. The third layer of listening is the most difficult to do and respond to, but it may be the most important for establishing trust in the therapeutic relationships with patients who are affected by BPPV. For example, patients' anxiety may result from fears about their dizziness, which may need to be defused and addressed through cognitive (rational-emotive behavior) counseling where these irrational beliefs and constrictive language structures are challenged. 15 16

Listening must be coupled with clinicians responding appropriately to patients' needs, requiring the skill of recognizing communication matches and mismatches. A communication match occurs when clinicians recognize patients' expressed needs and respond appropriately. As an example, a patient with BPPV may want to know how prevalent their condition is. The clinician should respond appropriately by meeting the informational need. A communication mismatch, however, may occur when a patient makes an affective statement indicating a social or emotional issue that merits further exploration. For example, with BPPV, symptoms of vertigo may appear suddenly and may be frightening for patients (e.g., mimicking that of a stroke), particularly for those who may have anxiety or suffer panic attacks as a result of the vertiginous symptoms. 17 Patients may remark that their symptoms are not only bothersome, but are terrifying. Clinicians who respond that there is nothing to be afraid of and that most patients feel that way fail to meet the expressed need, resulting in a communication mismatch. A door metaphor has been used to describe the exchange with affective statements representing a knock that clinicians must hear and respond to so the patient knows that their needs have been heard and appropriately addressed. 6 Appendix 1 contains a case study and clinical interaction activity that can be used as an exercise for students to identify the different layers of listening, communication matches, and mismatches for the case history/intake.

Recognizing and addressing patients' needs does not provide sufficient insight into the impact of BPPV on domains of the WHO-ICF model that pertain to the biophysical and psychosocial concerns. This also fails to quantify the magnitude of the patients' perceptions of the problem. Patients' responses to standardized self-assessment scales provide insight into the impact of dizziness on patients' lives, or dizziness-related quality of life (DRQoL). This information is essential to help identify areas where additional counseling is needed (e.g., fall risk, fear of falling, etc.), and subsequently serves as an anchor for counseling and for the establishment of a patient-centered clinical encounter. A commonly used standardized tool is the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI). 18 The DHI gauges patients' health-related quality of life by addressing the impact of dizziness on the WHO-ICF domains of activity limitations and participation restrictions. This questionnaire has 25 items that can be grouped into three content domains representing functional, emotional, and physical aspects of dizziness. 18 Other commonly used tools include the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale, 19 the Vestibular Disorders Activities of Daily Living Scale, 20 the Vertigo Handicap Questionnaire, 21 and the Vestibular Activities and Participation Measure. 22 For a more complete list, the reader is directed to Jacobson and Shepard's text. 23 An example of clinical and counseling usage of the DHI is found in the history and intake portion of Appendix 1 (lines 12 to 17).

Because secondary symptoms of panic and anxiety are significantly higher in patients with vertigo when compared to controls, 17 24 intake also should include screening assessments such as the Beck Anxiety Index or the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, when indicated. 25 26 The reader is again directed to Jacobson and Shepard's text 23 for a more complete list of validated measures commonly used with dizzy patients. Fortunately, many of these secondary issues subside once the vertigo is resolved. 24 However, some patients may continue to experience anxiety, depression, fear of falling, and so on, necessitating additional counseling and potentially a referral to a mental health professional. 27 Audiology students should be reminded that counseling for secondary issues is appropriate as long as it remains directly related to patients' vestibular dysfunction. Use of these tools can help to identify areas in need of additional attention while guiding personal adjustment counseling going into the diagnosis/treatment and patient education portions of the appointment.

Examination

We're coming to a point in the appointment where we might make you dizzy …

A patient-centric, therapeutic relationship is essential for the examination portion because patients may have doubt, or even fear, related to the procedures. For example, the vestibular evaluation relies heavily on examination of reflex arcs that include areas connected to but are beyond the vestibular system and require assessment in a dark room. Appropriate informational counseling regarding the function of the vestibular system and reasons for testing will assist in allaying any doubts or fears. Table 2 shows counseling tools, goals, and techniques for the examination. Providing explanation of the vestibular system during the examination phase will lay the groundwork for patient education.

Table 2. Examination.

| Goals | Tools | Counseling Skills |

|---|---|---|

| • Providing informational counseling about how the examination will be conducted and a warning of possibly unpleasant symptoms • Identifying appropriate timing for informational counseling during the examination • Maintaining open lines of communication between the clinician and the patient throughout testing |

• Exercise ( Appendix 1 ) | • Adaptation of test procedures based on previously identified comorbidities and/or physical limitations (e.g., range of motion of neck) • Focused, empathetic concern for the patients' feelings about the examination • Rational emotive counseling to address irrational fears or beliefs • Appropriate description and explanation during informational counseling, using individualized disclosure model |

A balance evaluation also has significantly more opportunities to cause uncomfortable symptoms than does a typical hearing evaluation due to neural networks that exist for vestibular autonomic regulation. Specifically, vestibulogastric connections can induce unpleasant symptoms such as pallor, sweating, nausea, and/or vomiting. 28 29 Given the vestibulo-ocular reflex helps maintain clear vision when the head is in motion, vestibulo-ocular reflex impairment can lead to visual symptoms such as blurred vision or nystagmus evoked from the BPPV. These symptoms may also cause patients to feel uncomfortable or uncertain about progressing through diagnostic testing. Patients should be briefed before certain tests are performed (e.g., head-shake tests, dynamic visual acuity tests, caloric testing), and definitely prior to the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, which is the essential test used to diagnose BPPV. The clinician should keep in mind that comprehensive vestibular testing is not recommended in patients who meet definitive diagnostic criteria for BPPV without other co-occurring vestibular symptoms. 9 At various points during the evaluation, patients should be made aware through informational counseling that examinations may evoke unpleasant symptoms and/or dizziness and should be assured and find comfort in the fact that the results from these tests will provide valuable information for diagnosis and management.

As mentioned earlier, many patients with BPPV also experience secondary anxiety and/or panic disorder. 17 24 Identifying the presence of anxiety, whether formally through intake or informally through observation, can help clinicians identify patients who may need personal adjustment counseling at critical points throughout their appointments. Sensitivity to patients' needs allows them to enter into the rehabilitation and postclinical stages of the journey with better certainty and clarity. An example dialogue is provided in the history and intake portion of Appendix 1 (line 5) when the patient expresses concern that her dizziness may be a brain tumor.

Diagnosis and Treatment Approach

Let's talk about some possibilities about how we can manage/treat this …

By this time in the appointment, the clinician has definitively diagnosed BPPV. The most common diagnosis would be BPPV of the posterior semicircular canal (61 to 97%), 30 31 32 33 followed by the horizontal canal (1 to 32%), 30 34 35 36 and the anterior canal (1 to 21%). 37 38 There may also be multicanal and/or bilateral involvement, but this is uncommon. Certainly, repositioning procedures and treatment recommendations would vary for different presentations of BPPV. Regardless of the type of BPPV, the diagnosis must be understandable to the patient, keeping in mind several counseling considerations. A summary of goals, tools, and counseling skills for this portion of the patient encounter are presented in Table 3 . The individualized disclosure model is based on the following assumptions: (1) patients vary in the amount of information they want and (2) time to internalize the diagnosis differs from patient to patient. 6 An example of delivering news of a diagnosis in a patient-centric, individualized disclosure manner is presented in the diagnosis, treatment, and education portion of Appendix 1 (lines 1 to 8). This type of dialogue provides the patient with an opportunity to ask questions that should be met with communication matches and continuer responses that address the information that is being requested. Depending on the patient, the diagnosis may include some informational counseling that would normally be covered in the patient education portion of this framework.

Table 3. Diagnosis and Treatment Approach.

| Goals | Tools | Counseling Skills |

|---|---|---|

| • Providing the diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo to the patient in a sensitive and patient-centric manner • Allowing opportunities for the patient to ask questions • Collaborating in shared decision making for exploring treatment options • Discussion of treatment options in a patient-centric manner |

• Anatomical model for explaining the diagnosis and management approaches • Dizziness-related quality of life measures to relate personal impact to diagnosis and treatment options • Decisional balance matrix (formal or informal) • Exercise ( Appendix 1 ) |

• Individualized disclosure model • Shared decision making • Realistic expectations and associated risks o Success, recurrence, and spontaneous resolution rates o Fall risk o Activity limitations during observation • Appropriate description and explanation during informational counseling that avoids clinical jargon |

If the patient is prepared to discuss treatment options, recommendations should be based on their needs/concerns and their patient story, not solely from the diagnosis. Reflective listening of the clinician during the case history and the DRQoL measures of impact should inform how treatment options are presented. The clinician should reflect on the negative impact of the disorder, explore patients' willingness to pursue treatment, and, if needed, explore cost-benefit scenarios to guide them in making informed decisions. An example dialogue is provided in the diagnosis, treatment, and education portion of Appendix 1 (lines 9 to 17). Patients' motivations to pursue treatment options for BPPV depend on the stage in patients' journeys, presence of any denial about the diagnosis, perception of the urgency of the situation, and impact of the disorder on DRQoL.

Shared decision making and patient-centric counseling techniques, such as the individualized disclosure model, can be used to explore some of the following treatment options for BPPV: (1) repositioning procedures as initial therapy, (2) observation with follow-up as a viable, initial option, and (3) additional habituation-based vestibular rehabilitation. 9 The resolution rates for BPPV are relatively high and can reach 100% with multiple treatment sessions for posterior canal BPPV. 39 40 41 Moreover, repositioning maneuvers for horizontal and anterior canal BPPV have also been found to be highly efficacious. 42 43 These rates should be used to provide patients with realistic expectations for full resolution of symptoms and full recovery from the issue. Additionally, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) guidelines advocate for providing the option of vestibular rehabilitation exercises for habituation-based management of BPPV (e.g., Cawthorne-Cooksey and Brandt-Daroff exercises), though clearly the evidence supports use of repositioning maneuvers as primary intervention unless there are valid reasons to select an alternative option. 9 If repositioning procedures or habituation exercises are chosen, counseling should be provided on the potentially unpleasant symptoms that may be associated with the procedure(s) or exercise(s). Audiologists may have to deal with treatment adherence issues for patients returning for additional repositioning exercises and/or if they are assigned home-based habituation exercises.

However, when informed that this disorder may spontaneously recover (20% by 1 month; 50% by 3 months), 9 clinicians need to be prepared for patients opting for observation in lieu of repositioning procedures. If this is the case, patients should be reminded about their self-ratings of DRQoL and counseled about fall risk associated with untreated BPPV and other activity restrictions that should be observed during the period of watchful waiting. 9 11 If patients are ambivalent in selecting between treatment and observation, a patient-centered approach of reflecting back to the impact of the disorder and the cost-benefit assessment can help guide patients to a decision.

Patient Education

BPPV is a specific diagnosis, and each word describes the condition. Benign means that …

The AAO-HNS guidelines state that patient education is a key component of the care plan for those with BPPV. 9 A summary of associated goals, tools, and counseling skills are provided in Table 4 . Patient education provides an opportunity to understand the condition and its functional impact on patients' daily activities and DRQoL. Patients can be provided with supporting materials such as handouts and/or a list of websites for more information can also be provided to aid in comprehension. Additionally, a list of commonly asked questions and their respective answers are provided in a table in the AAO-HNS guidelines. 9 According to Bhattacharyya and colleagues, patient education should convey the following: (1) an understanding of the condition and name, (2) rate for recurrence and co-occurring conditions causing higher risk for recurrence, (3) other factors that predispose them to BPPV, (4) fall risk associated with BPPV, and (5) importance of follow-up. 9

Table 4. Patient Education.

| Goals | Tools | Counseling Skills |

|---|---|---|

| • Explaining the condition and its functional impact on daily activities • Relating rates of recurrence and comorbidities that cause higher rates of recurrence • Providing information on fall risk associated with BPPV • Emphasizing the importance of follow-up during and after management • Educating patients on symptoms that indicate a disorder other than BPPV, and referring for additional medical attention when indicated • Providing recommendations against continuation of vestibular suppressant medications and postprocedural activity restrictions for common presentation of BPPV |

• Tangible supports to aid in comprehension and retention of information o Patient education handouts o List of websites for more information o Anatomical model or illustration • AAO-HNS (2017) Frequently Asked Questions 9 • Exercise ( Appendix 1 ) |

• Individualized disclosure model • Integration of patient story and dizziness-related quality of life impact into the explanation of the vestibular disorder • Succinct explanation of the condition, functional impacts, and implications • Personal adjustment counseling to address fears or anxiety about the pathology or diagnosis • Identification of motivation levels to assure adherence to treatment and appropriate follow-up procedures |

AAO-HNS, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery; BPPV, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

Several elements are important in assuring an understanding of any condition, including BPPV. First, the name of the condition should be provided and succinctly explained using the individualized disclosure model. Clinicians should incorporate portions of patients' stories and perceptions of their problems into these explanations. This can be particularly powerful because it shows that the clinician has heard their stories. In addition, many patients with BPPV will have secondary anxiety or panic disorders, which merit additional personal adjustment counseling. Through informational counseling, clinicians can help to dispel doubt, fear, and uncertainty that, for example, the vertigo may have been caused by a stroke or is related to another condition. Patients need to be advised that recurrence rates can be as high as 36% and their prevalence increases over time. 44 In addition, those with head trauma may be at risk for higher rates of recurrence. 45 Other comorbid conditions that predispose patients to having BPPV include viral labyrinthitis, Meniere disease, migraine, stroke, hypertension, osteoporosis, and increased blood lipids. 9 46 47 The AAO-HNS panel hypothesizes that relating rates and causes for recurrence can help patients to identify such a recurrence and help them seek treatment sooner.

Informational and personal adjustment counseling also should be used for educating the patient about increased fall risk associated with BPPV, 11 48 49 as well as key components of home safety (e.g., grab bars in the bathroom). Personal adjustment counseling and assessment of patient motivation are integral to assuring patients' adherence to treatment recommendations for those who select observation as initial treatment. When presented with this information, some patients may begin to respond with affective statements as to why they are not able or willing to follow such recommendations. If this occurs, clinicians should recount patients' stories and the related impact of BPPV on DRQoL to help increase motivation, and revisit treatment options if necessary. Counseling skills for addressing treatment issues are covered in another article in this issue.

Similar strategies should be used for discussion of follow-up procedures that may differ, depending if patients select canalith repositioning treatment or watchful waiting. For those who opt for watchful waiting, it is especially important to underscore the importance of returning for evaluation to determine if the BPPV has spontaneously resolved and to discuss treatment options if resolution has not occurred. Follow-up is also important to confirm resolution of BPPV symptoms after treatment with repositioning procedures and to rescreen or reevaluate for fall risk and any secondary psychiatric issues. Regardless of treatment option, all patients should be educated on symptoms indicating the presence of disorders that need additional and timely medical attention (e.g., sudden hearing loss, nonpositional vertigo, nausea, emesis, etc.). Some patients may have uncompensated peripheral vestibulopathy that needs to be addressed after clearing the BPPV. 50 51 Although most do not continue to experience BPPV-related anxiety after successful treatment, it is important for the clinician to consider this possibility with an appropriate follow-up anxiety screening to confirm if a referral is needed for further psychological assessment. Return appointments are also an appropriate time to remeasure DRQoL to document outcomes with regard to activity limitations and participation restrictions and potentially identify matters that need further examination (i.e., residual or new symptoms).

In addition to the aforementioned elements for patient education, other recommendations in the guidelines are also appropriate to include during the patient education portion of the appointment. The AAO-HNS guidelines provided evidence for strong recommendations against vestibular suppressant medications and postprocedural activity restrictions, particularly after treatment of posterior canal BPPV with repositioning maneuvers. 9 The use of cervical collars and/or activity limitations (e.g., sleeping with the head elevated, not moving the head vertically, etc.) has not been found to add any additional effectiveness. 52 Certainly, it is not within the scope of practice of audiologists to prescribe or dispense pharmaceutical drugs. However, there is no evidence to support the use of vestibular suppressant medication to treat BPPV. Patients should be encouraged to discuss this with their physician because these drugs are often used as an initial management for any dizziness/imbalance when their appropriate use is actually for acute symptoms of vertigo-nausea only. Prolonged usage decreases access to important vestibular information and has the potential to cause harm (i.e., falls, delay mechanisms of central compensation, and other related side effects of such medications). 9 53 54

Conclusion

In this article, patient-centered strategies were applied to counseling the dizzy patient with BPPV. Many of the same counseling approaches can be used for developing a trusting relationship between the clinician and the patient. The recommendations from the AAO-HNS 2017 guidelines easily integrate into evidence-based counseling practices in audiology. The information provided in this article should serve as examples of targeted didactic and experiential learning opportunities for audiology students. Examples of engagement activities for students are provided in Appendix 2 . By creating a solid theoretical and practical foundation for students, these tools can lend themselves to increasing preparedness for when audiology students encounter those with BPPV. As with coursework dedicated to counseling those with hearing loss or tinnitus, evidence-based counseling theories and strategies should also be discussed and applied to encounters with dizzy patients. Students should also be able to exhibit an understanding of additional considerations for those who have psychological disturbances secondary to BPPV. Still, much research is needed in the area of counseling dizzy patients, particularly with regard to the counseling needs of this population, as well as their respective patient journey and motivations.

Appendix 1. Case Study/Clinical Interaction Activity

Instructions

Please use the following case study and mock dialogues for students to identify the layer of listening, matches, and communication mismatches for the intake/case history, examination, diagnosis and treatment, and patient education stages of the patient journey. Please have students identify patients' needs, layer of listening, communication matches/mismatches, and use of the patient disclosure model by circling the correct items. (Please note correct answers appear in bold.)

Case Information

Mrs. Jones is a 75-year-old female who has experienced positional vertigo with lying supine for 6 months. She sleeps in her recliner because there is no vertigo when her head is elevated. This is concerning to her family and she finally went to her doctor after almost falling off a step ladder while helping her daughter hang curtains while redecorating—an activity she has always done and had enjoyed. Her daughter is very concerned because her mother almost fell and seemed “very out of sorts.” The patient is quite concerned because she can no longer do some of things she enjoys. Her doctor told her she was getting older and she should just learn to live with it. He wrote a prescription for meclizine, but told her to stop taking it if her symptoms didn't get better. He didn't seem too concerned and stated that many old people get dizzy.

| Need Expressed 1 = None 2 = Informational 3 = Affective |

Layer of Listening Needed 1 = Information for Diagnosis/Treatment 2 = Informational Needs 3 = Affective Statements |

Match or Mismatch? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intake/Case History | |||

| 1. Au.D.: Good morning, Ms. X. What brings you here today? | |||

| P: Hi. The room seems to spin. | 1 2 3 | ||

| 2. Au.D.: How long has this been going on? | |||

| P: Yes, ∼6 months. I'm scared. | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 3. Au.D.: Don't be scared. Many people your age have this problem. | Match Mismatch |

||

| P: I'm frightened and angry that no one understands and this has happened to me! | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 4. Au.D.: Tell me more about how you feel . . . |

Match

Mismatch |

||

| P: My life changed in an instant and I'm worried I may have a brain tumor! My doctor said I just need to learn to live with it. No one understands! | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 5. Au.D.: It sounds like you feel that your life has changed dramatically and that you are concerned that this condition may be a symptom of something very serious. You believe that no one understands how you feel and they tell you it is common. |

Match

Mismatch |

||

| P: Exactly! It may be a common problem, but it is ruining my life! I can't even sleep in my own bed. I have to sleep in my recliner. | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 6. Au.D.: I understand! Not being able to sleep in your own bed is frustrating! Can you tell me specific times when the room spins, other than when lying down? |

Match

Mismatch |

||

| P: Well, I was helping my daughter hang curtains and I almost fell off the ladder when I looked up to hang the curtains on the rod. | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 7. Au.D.: What I hear you say is that when you are looking up, the room spins. |

Match

Mismatch |

||

| P: Yes! Why does it happen only when I look up? | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 8. Au.D.: I have a pretty good idea of what may be going on here. But, the results of the examination today will tell us more. I'd like for you to fill out the Dizziness Handicap Inventory, which can help us further obtain information we need. I'll give you an opportunity to complete the questionnaire. (Patient completes it and it is scored by the Au.D.) |

Match

Mismatch |

||

| 9. Au.D.: From your answers, it seems as though this condition is causing a significant impact on your life. | |||

| P: The questions helped me to realize things I wasn't aware of . . . (Patient pauses; looks downward.) | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 10. Au.D.: Can you tell me more about that? What do you mean? |

Match

Mismatch |

||

| P: The questions helped me to realize that I've been afraid to leave my home. | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 11. Au.D.: Ms. X, I understand and dizziness can be very scary. (Places hand on patient's shoulder.) |

Match

Mismatch |

||

| Examination | |||

| 1. Au.D.: Ms. X, now that I have had an opportunity to speak with you about your dizziness. I have a good idea what we might be dealing with here, but I need to conduct an exam to confirm. The procedure requires for us to observe your eyes. Because your inner ear is way down in the skull bone, we have to rely on other connections that the inner ear has with other parts of your body. One important connection for balance is with the eyes so things don't get blurry when our heads move. | |||

| 2. Au.D.: We're coming to a part of the appointment where we might make you dizzy. But this is also an important part in helping determine what's going on. You will be sitting upright on this exam table and I will be having you lie backward such that your head will tilt beyond the edge of the table. Because you said it happens more often when rolling over in bed to the right, we will start on the right side, then do the left. | |||

| 3. Au.D.: Relax and I will be bracing you during the entire procedure. There is nothing to be afraid of. | Match Mismatch |

||

| P: You don't understand! I will get sick to my stomach and I'm embarrassed I may throw up! | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 4. Au.D.: What I hear you say is that you're afraid that it might make you sick to your stomach. Yes, that does happen sometimes and we're prepared for that. Simply let me know if you feel nauseous and we can stop and take necessary precautions. |

Match

Mismatch |

||

| Diagnosis and Treatment/Patient Education | |||

|

1. Au.D.: Based on my examination, you have benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. (Hands the patient education handout to Ms. X.) Each word describes the issue.

Benign

is always good news, it means it's not harmful.

Paroxysmal

means that the attacks are sudden and intense.

Positional

means that these attacks come on with certain changes in position, like you going from sitting to laying down in bed or when you moved your head to look up to hang the curtains. And lastly,

vertigo

, of course, means the sensation of spinning. So, they're sudden spinning attacks that come on with certain changes in position.

Let's look at this picture that shows your balance system in your inner ear, so I can show you what's going on. You've got two parts: the first part consists of these two structures. They have little calcium crystals that are embedded in the membrane on top of this sensory structure. Now the second part is made up of these loops. These loops don't work with crystals. What happened is that the little crystals got loose and went into the loops where they don't belong. |

|||

| P: Uh, sounds complicated . . . | |||

| 2. Au.D.: Ms. X, yes, it can be, but your case is pretty straightforward. Can you tell me your understanding of what I just told you? | Match or Mismatch? Use of Individual Disclosure Model? Yes No |

||

| P: Let me see, it sounds like some of those crystals have gotten loose and gone to places they shouldn't be. Is that right? | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 3. Au.D.: (Nods.) Exactly, and the movement of the crystals in the loops creates sensations of the room spinning when you move tilt your head back or when you lay down. | Match or Mismatch? Use of Individual Disclosure Model? Yes No |

||

| P: Oh, I think I understand. | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 4. Au.D.: Would you like to now more detail about the canals involved? | Match or Mismatch? Use of Individual Disclosure Model? Yes No |

||

| P: Oh no, that's OK. I want to know what can be done to cure it. | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 5. Au.D.: Well, the good news is that treatment options have a very high success rate, nearing 100% |

Match

or Mismatch?

Use of Individual Disclosure Model? Yes No |

||

| P: That's good news. What does the treatment involve? | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 6. Au.D.: Some repositioning movements, similar to what we did in the exam. |

Match

or Mismatch?

Use of Individual Disclosure Model? Yes No |

||

| P: Oh, goodness! Is that necessary? | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 7. Au.D.: In some cases, it gets better on its own, but it may take up to 3 months. Also, because you have migraine headaches, this makes you more susceptible to getting this again. |

Match

or Mismatch?

Use of Individual Disclosure Model? Yes No |

||

| P. Three months . . . doesn't seem too long, but . . . | |||

| 8. Au.D.: You had mentioned how you have restricted your activities and that you're afraid you might fall. | Match or Mismatch? Use of Individual Disclosure Model? Yes No |

||

| P: Yes, that's right. OK. Let's do the repositioning work. Do you have some information I can take with me? | 1 2 3 | 1 2 3 | |

| 9. Au.D.: Yes, you've got your handout and here is a sheet with answers for frequently asked questions. But I'm always here to answer any questions you might have later. |

Match

or Mismatch?

Use of Individual Disclosure Model? Yes No |

||

Appendix 2. Example Engagement Activities for Students

Role-playing to answer commonly asked questions about benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV; see Bhattacharyya et al 9 p. S35–S36, for a table).

Writing a personalized script for the examination, diagnosis, and patient education portions of the appointment with a patient vignette as direction for individualized disclosure.

Creating a clinician cheat sheet for statistics on success rates, recurrence rates, conditions associated with higher rates of BPPV, list of symptoms that require further attention or follow-up.

Determining counseling needs from a case study.

Creating a patient education handout for BPPV.

References

- 1.Meibos A, Muñoz K, Schultz J et al. Counselling users of hearing technology: a comprehensive literature review. Int J Audiol. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2017.1347291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Searchfield G D, Kaur M, Martin W H. Hearing aids as an adjunct to counseling: tinnitus patients who choose amplification do better than those that don't. Int J Audiol. 2010;49(08):574–579. doi: 10.3109/14992021003777267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cima R F, Maes I H, Joore M Aet al. Specialised treatment based on cognitive behaviour therapy versus usual care for tinnitus: a randomised controlled trial Lancet 2012379(9830):1951–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.Guidelines for audiologists providing informational and adjustment counseling to families of infants and young children with hearing loss birth to 5 years of ageAvailable at:http://www.asha.org/policy/GL2008-00289/. 2008. Accessed August 30, 2017

- 5.Moyer V A; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement Ann Intern Med 201215703197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark J G, English K.Counseling-Infused Audiologic Care London, UK: Pearson; 20141–26., 84–103 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrera I, Corso R, Macpherson D. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brooks; 2003. Skilled Dialogue: Strategies for Responding to Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization.International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels S P, Schwartz S Ret al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017156(3 Suppl):S1–S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strupp M, Dieterich M, Brandt T. The treatment and natural course of peripheral and central vertigo. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:505–515. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oghalai J S, Manolidis S, Barth J L, Stewart M G, Jenkins H A. Unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in elderly patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(05):630–634. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts R A, Abrams H, Sembach M K, Lister J J, Gans R E, Chisolm T H. Utility measures of health-related quality of life in patients treated for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Ear Hear. 2009;30(03):369–376. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31819f316a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roland L, Sinks B, Goebel J. San Diego, CA: Plural; 2016. The vertigo case history; pp. 163–208. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers C R. Carl Rogers on the development of the person-centered approach. Person-Centered Review. 1986;1(03):257–259. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis A. Oxford, UK: Lyle Stuart; 1962. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis A. Rational psychotherapy and individual psychology. J Individual Psychol. 1956;13(01):38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahraman S S, Arli C, Copoglu U S, Kokacya M H, Colak S. The evaluation of anxiety and panic agarophobia scores in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo on initial presentation and at the follow-up visit. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017;137(05):485–489. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2016.1247986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson G P, Newman C W. The development of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116(04):424–427. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1990.01870040046011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell L E, Myers A M. The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50A(01):M28–M34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.1.m28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen H S, Kimball K T. Development of the vestibular disorders activities of daily living scale. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(07):881–887. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.7.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yardley L, Putman J. Quantitative analysis of factors contributing to handicap and distress in vertiginous patients: a questionnaire study. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1992;17(03):231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1992.tb01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alghwiri A A, Whitney S L, Baker C E et al. The development and validation of the vestibular activities and participation measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(10):1822–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobson G P, Newman C W, Piker E G. San Diego, CA: Plural; 2016. Assessing dizziness-related quality of life; pp. 163–207. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollak L, Klein C, Rafael S, Vera K, Rabey J M. Anxiety in the first attack of vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128(06):829–834. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980300454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck A T, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer R A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(06):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zigmond A S, Snaith R P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(06):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes S, Padgham N D.A review of the burden of vertigo J Clin Nurs 201120(19–20):2690–2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Money K E, Lackner J R, Cheung R SK. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1996. The autonomic nervous system and motion sickness; pp. 147–173. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Treisman M.Motion sickness: an evolutionary hypothesis Science 1977197(4302):493–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De la Meilleure G, Dehaene I, Depondt M, Damman W, Crevits L, Vanhooren G. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the horizontal canal. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;60(01):68–71. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.60.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Honrubia V, Baloh R W, Harris M R, Jacobson K M. Paroxysmal positional vertigo syndrome. Am J Otol. 1999;20(04):465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moon S Y, Kim J S, Kim B K et al. Clinical characteristics of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in Korea: a multicenter study. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21(03):539–543. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruckenstein M J. Therapeutic efficacy of the Epley canalith repositioning maneuver. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(06):940–945. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cakir B O, Ercan I, Cakir Z A, Civelek S, Sayin I, Turgut S. What is the true incidence of horizontal semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(03):451–454. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fife T D. Recognition and management of horizontal canal benign positional vertigo. Am J Otol. 1998;19(03):345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macias J D, Lambert K M, Massingale S, Ellensohn A, Fritz J A. Variables affecting treatment in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(11):1921–1924. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200011000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herdman S, Tusa R, Clendanial R. Robinson. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Theime-Verlag; 1993. Eye movement signs in vertical canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; pp. 385–387. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson L E, Morgan B, Fletcher J C, Jr, Krueger W W. Anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: an underappreciated entity. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28(02):218–222. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000247825.90774.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruintjes T D, Companjen J, van der Zaag-Loonen H J, van Benthem P P. A randomised sham-controlled trial to assess the long-term effect of the Epley manoeuvre for treatment of posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Clin Otolaryngol. 2014;39(01):39–44. doi: 10.1111/coa.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang S B, Li L, He H Y. The efficacy of Epley procedure for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of the posterior semicircular canal. J Youjiang Med University for Nationalities. 2010;2:7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie K, Du S W, Gao J J, Shou G L, Jian H Y, Li Y Z. Clinical efficacy of Epley procedure for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo of posterior semicircular canal. Chin J Gen Pract. 2012;2:20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim J S, Oh S Y, Lee S H et al. Randomized clinical trial for geotropic horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2012;79(07):700–707. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182648b8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yacovino D A, Hain T C, Gualtieri F. New therapeutic maneuver for anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Neurol. 2009;256(11):1851–1855. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hilton M P, Pinder D K. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD003162. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003162.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon C R, Levite R, Joffe V, Gadoth N. Is posttraumatic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo different from the idiopathic form? Arch Neurol. 2004;61(10):1590–1593. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.10.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parnes L S, Agrawal S K, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) CMAJ. 2003;169(07):681–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F et al. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(07):710–715. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brandt T, Dieterich M. Vestibular falls. J Vestib Res. 1993;3(01):3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imbaud Genieys S. [Vertigo, dizziness and falls in the elderly] Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2007;124(04):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.aorl.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pollak L, Davies R A, Luxon L L. Effectiveness of the particle repositioning maneuver in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with and without additional vestibular pathology. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23(01):79–83. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200201000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roberts R A, Gans R E, Kastner A H, Listert J J. Prevalence of vestibulopathy in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo patients with and without prior otologic history. Int J Audiol. 2005;44(04):191–196. doi: 10.1080/14992020500057715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts R A, Gans R E, DeBoodt J L, Lister J J. Treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: necessity of postmaneuver patient restrictions. J Am Acad Audiol. 2005;16(06):357–366. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.16.6.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hain T C, Uddin M. Pharmacological treatment of vertigo. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(02):85–100. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cesarani A, Alpini D, Monti B, Raponi G; ENT Department, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.The treatment of acute vertigo Neurol Sci 20042501S26–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]