Summary

Background

Inclusion health focuses on people in extremely poor health due to poverty, marginalisation, and multimorbidity. We aimed to review morbidity and mortality data on four overlapping populations who experience considerable social exclusion: homeless populations, individuals with substance use disorders, sex workers, and imprisoned individuals.

Methods

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Library for studies published between Jan 1, 2005, and Oct 1, 2015. We included only systematic reviews, meta-analyses, interventional studies, and observational studies that had morbidity and mortality outcomes, were published in English, from high-income countries, and were done in populations with a history of homelessness, imprisonment, sex work, or substance use disorder (excluding cannabis and alcohol use). Studies with only perinatal outcomes and studies of individuals with a specific health condition or those recruited from intensive care or high dependency hospital units were excluded. We screened studies using systematic review software and extracted data from published reports. Primary outcomes were measures of morbidity (prevalence or incidence) and mortality (standardised mortality ratios [SMRs] and mortality rates). Summary estimates were calculated using a random effects model.

Findings

Our search identified 7946 articles, of which 337 studies were included for analysis. All-cause standardised mortality ratios were significantly increased in 91 (99%) of 92 extracted datapoints and were 11·86 (95% CI 10·42–13·30; I2=94·1%) in female individuals and 7·88 (7·03–8·74; I2=99·1%) in men. Summary SMR estimates for the International Classification of Diseases disease categories with two or more included datapoints were highest for deaths due to injury, poisoning, and other external causes, in both men (7·89; 95% CI 6·40–9·37; I2=98·1%) and women (18·72; 13·73–23·71; I2=91·5%). Disease prevalence was consistently raised across the following categories: infections (eg, highest reported was 90% for hepatitis C, 67 [65%] of 103 individuals for hepatitis B, and 133 [51%] of 263 individuals for latent tuberculosis infection), mental health (eg, highest reported was 9 [4%] of 227 individuals for schizophrenia), cardiovascular conditions (eg, highest reported was 32 [13%] of 247 individuals for coronary heart disease), and respiratory conditions (eg, highest reported was 9 [26%] of 35 individuals for asthma).

Interpretation

Our study shows that homeless populations, individuals with substance use disorders, sex workers, and imprisoned individuals experience extreme health inequities across a wide range of health conditions, with the relative effect of exclusion being greater in female individuals than male individuals. The high heterogeneity between studies should be explored further using improved data collection in population subgroups. The extreme health inequity identified demands intensive cross-sectoral policy and service action to prevent exclusion and improve health outcomes in individuals who are already marginalised.

Funding

Wellcome Trust, National Institute for Health Research, NHS England, NHS Research Scotland Scottish Senior Clinical Fellowship, Medical Research Council, Chief Scientist Office, and the Central and North West London NHS Trust.

Introduction

Inclusion health is a research, service, and policy agenda that aims to prevent and redress health and social inequities among people in extremely poor health due to poverty, marginalisation, and multimorbidity.1 The association between socioeconomic status and health outcomes is well established. However, these commonly observed social gradients in health do not capture the full extent of health inequities for individuals who experience considerable social exclusion.

Previous research has described the high prevalence of substance use disorders in homeless populations,2 prisoners,3 and sex workers,4 and the increased prevalence of homelessness in prisoners5 and sex workers.6 These marginalised populations have common intersecting characteristics and adverse life experiences that lead to considerable social exclusion, making them powerful determinants of marginalisation in high-income settings.7

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

A comprehensive body of research exists on the health effect of inequity, much of which focuses on disparities in morbidity and mortality, and is based on common measures of socioeconomic status, such as neighbourhood deprivation and occupational class. A consistent association has been found between ill health and increasing levels of social deprivation, which has underpinned a broad range of social policies and public health initiatives. Such analyses cannot adequately assess the extent of health inequity faced by individuals who experience considerable social exclusion. In preparation for this Review, we searched the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, and Embase databases for articles published between Jan 1, 2005, and Sept 30, 2013. We searched for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, cohort studies, and cross-sectional studies containing morbidity and mortality outcomes for the four inclusion health populations of interest (substance use disorders, homeless populations, prisoners, and sex workers). We only included full-text articles published in English. Full search terms are listed in the appendix. The studies identified described the highly overlapping nature of inclusion health populations, the increased risk factors for disease, and poor mortality outcomes compared with the general population. Previous systematic reviews have analysed health outcomes of individual inclusion health populations, but none have examined the populations together.

Added value of this study

Our systematic review and meta-analysis provides the first comprehensive examination to date of morbidity and mortality outcomes across a range of inclusion health populations. We found that the extent of the health inequity seen in our inclusion health populations greatly exceeded that previously observed between populations with high and low socioeconomic status and was consistent across inclusion health populations. Mortality rates are extremely high across the International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision disease categories in inclusion health populations, and our review is the first to show that relative risks are consistently higher in female than male individuals.

Implications of all the available evidence

The extreme burden of disease experienced by inclusion health populations demands a cross-sectoral response to prevent considerable social exclusion and an improvement in services that work with these populations. Our analyses focused on relative measures of mortality and therefore future work should examine absolute measures in greater detail. Inclusion health populations are often invisible within routine health data. This limitation can be addressed by modifying the instruments used to collect such data or through data linkage studies. Services that provide for inclusion health populations should aim to deliver health and social services for overlapping marginalised groups to tackle the poor health outcomes found in this study. These services should also have a greater focus on prevention and management of more common conditions in addition to those traditionally considered high risk for inclusion health groups.

When considered separately, marginalised populations have been shown to have high all-cause mortality.8, 9, 10 However, despite the considerable overlap in risk factors and the substantially increased mortality observed in these populations, no previous review has examined the outcomes of these groups together.

No universally agreed theoretical framework exists to describe inclusion health. In this Article, we build on existing social exclusion theory and consider the so-called linked and cumulative factors and processes that confound individual and group capacity for hope, opportunity, reciprocity, and participation.11 Our analysis is also informed by an intersectionality perspective, which focuses on how social characteristics combine to have an effect on health.2, 12

Our systematic review therefore aims to examine mortality and morbidity in homeless populations, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders, who experience considerable exclusion.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, and Embase for articles published between Jan 1, 2005, and Oct 1, 2015. Full search terms are provided in the appendix. We searched for articles about the populations of interest (homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders, excluding cannabis and alcohol use) from systematic reviews, meta-analyses, interventional studies, and observational studies that had morbidity and mortality outcomes. We included studies identified from references of included articles. We only included full-text articles published in English that were done in high-income countries (classified according to the World Bank classification13). We excluded studies with only perinatal outcomes and did not include data on perinatal outcomes from studies that otherwise met our inclusion criteria. We excluded articles that limited the study population to individuals with a specific health condition and studies that recruited participants exclusively from intensive care or high dependency hospital units.

We recognise that social exclusion has a major effect on health in other social groups, including Gypsies and Travellers, migrants, ethnic minorities, indigenous communities, and sexual and gender minorities. Although these groups experience social exclusion in many high-income settings, they were considered beyond the scope of this systematic review.

Data analysis

RWA screened titles, abstracts, and full texts using Covidence systematic review software. All authors contributed to data extraction, and data were double-checked by a second researcher (RWA, EJT, GH, or SVK).

Extracted items included study design, year or years of study, country, number of participants, primary outcomes, and summary descriptions of the study population. We tried to contact authors if we were unable to locate papers or required additional information about the data or study.

We attempted to identify and exclude duplicate data from research studies presented in separate publications. For cases in which we identified multiple studies with duplicated or overlapping data (by population, time, place, and outcome) we selected the study with the largest or most representative sample size, and when these were also similar, we present the most recent study. We followed the PRISMA reporting guidelines in the presentation of our manuscript. A review protocol was not published before this review was done.

Outcomes included were measures of morbidity and mortality for conditions defined in the International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10). Outcomes were reported using a variety of measures. To ensure maximum comparability across studies for mortality outcomes, we extracted, in order of preference, the first of the following measures: standardised mortality ratio (SMR), hazard ratio, mortality rate ratio, or crude mortality rate. For consistency with most studies included in this Article, we have not multiplied SMRs by 100. In our results, a value of 1 equates to no difference between the expected and observed mortality rate. For morbidity outcomes, we extracted, in order of preference, the first of the following measures: prevalence, incidence, prevalence risk ratio, incidence rate ratio, prevalence odds ratio, or incidence odds ratio. When available, we used data in which the comparison group was a socially deprived population or measures were adjusted for area-based or income-based deprivation.

A link to all extracted data is included in the appendix. For the quantitative findings analysed in this study, we focused the synthesis on SMRs. SMRs for all-cause mortality and by ICD-10 disease category were summarised in forest plots. We anticipated high levels of heterogeneity, and therefore did summary estimates with random effects models using Stata version 13. We used the I2 statistic to indicate the proportion of total variation in study estimates due to heterogeneity.14 We explored potential sources of heterogeneity by stratifying the analyses by country and by inclusion health population group.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

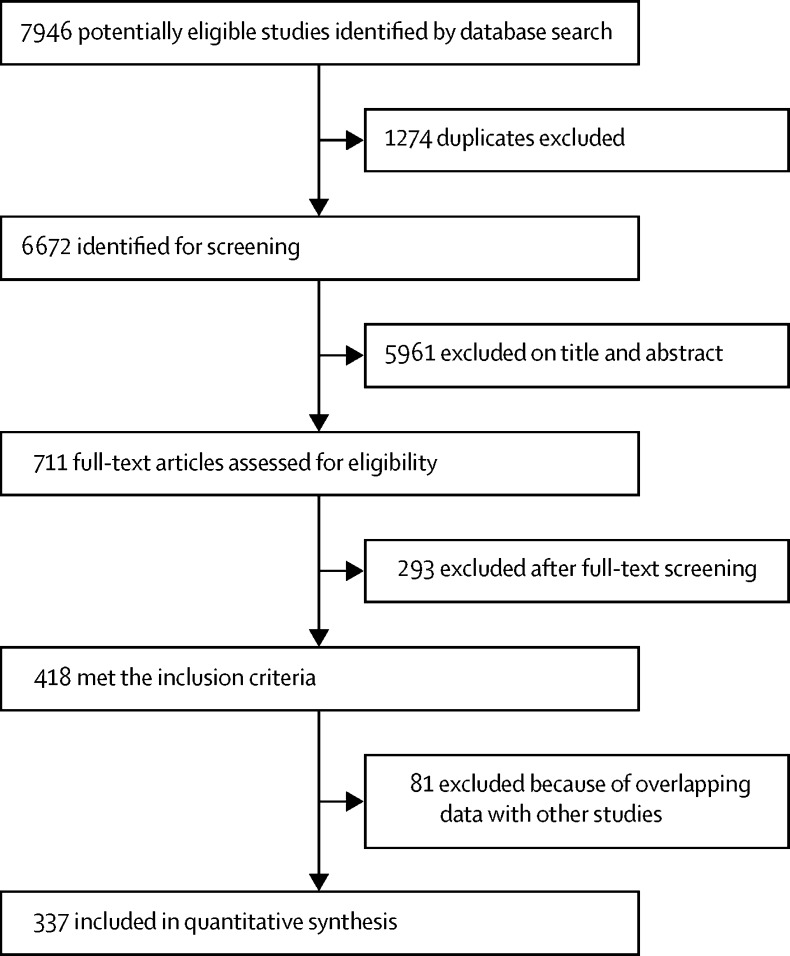

We identified 7946 articles, of which 1274 were duplicates (figure 1). Of the 711 full-text articles retrieved, 418 met the inclusion criteria. We excluded a further 81 articles because of overlapping data. A total of 337 studies were included in this Article, which included 2835 datapoints (ie, effect estimates for a unique population) after the removal of 384 duplicates.

Figure 1.

Study selection

The studies were from 38 countries (appendix). The USA contributed 698 datapoints, Australia contributed 460, Sweden contributed 309, Canada contributed 257, and the UK contributed 234. Populations with substance use disorders were the most studied subgroup, accounting for 1193 (42·1%) of 2835 datapoints, followed by prisoners (769 [27·1%]), homeless populations (754 [26·6%]), and sex workers (119 [4·2%]).

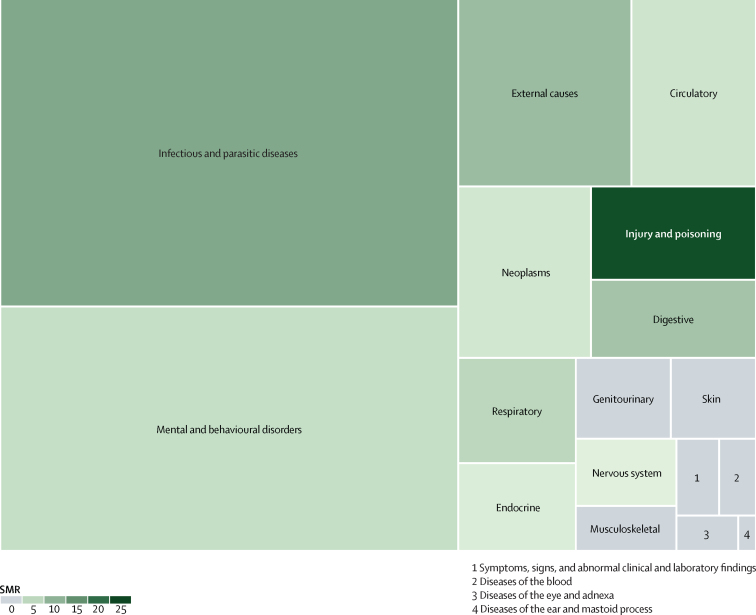

Infectious diseases and mental and behavioural disorders were the two most studied ICD-10 categories with infectious diseases accounting for 898 (31·6%) of 2835 datapoints, and mental and behavioural disorders accounting for 715 (25·2%) datapoints (figure 2, appendix p 4). Injury and poisoning only accounted for 98 (3·4%) of all extracted datapoints.

Figure 2.

Treemap summarising the amount of available data grouped according to the ICD-10 disease categories and summary estimates of SMRs

Box sizes indicate the total number of datapoints included in this Article. SMRs used are summary estimates for the ICD-10 disease categories for both sexes combined. Grey boxes (SMR of 0) indicate that none of the studies included in this Article reported SMR for both sexes combined. ICD-10= International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision. SMR=standardised mortality ratio.

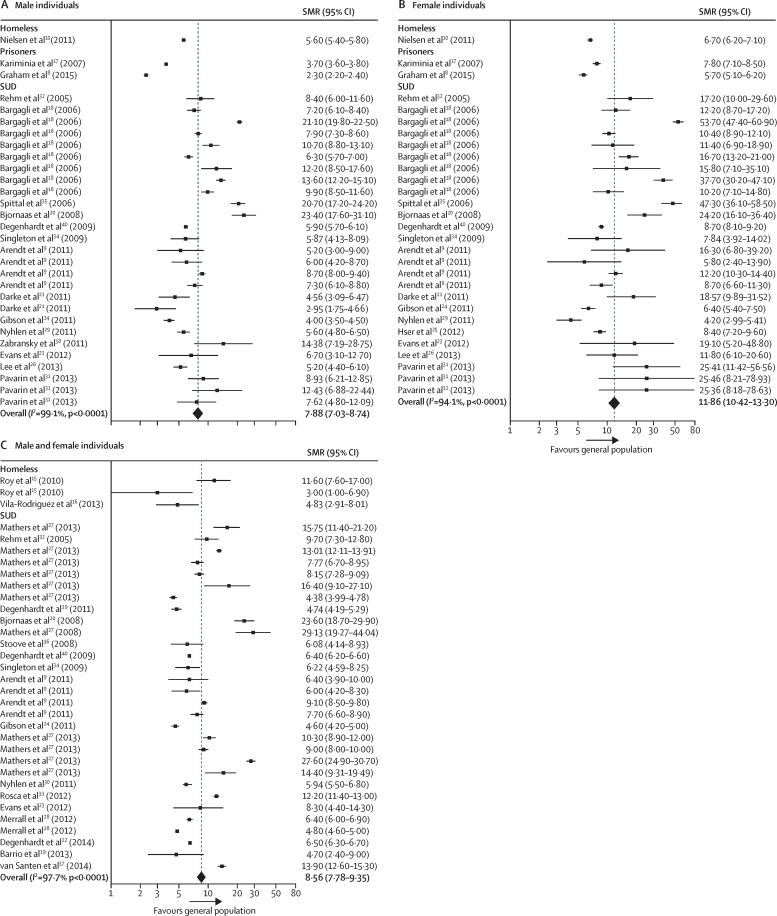

Our all-cause meta-analyses focused on SMRs and included 29 studies,8, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 which contributed 92 datapoints (table, figure 3, appendix). 91 (99%) of the 92 all-cause SMRs were increased and overall we estimated that summary all-cause SMRs were higher in female individuals (11·86 [95% CI 10·42–13·30]; I2=94·1%; figure 3) than male individuals (7·88 [7·03–8·74]; I2=99·1%; figure 3). We provide summary estimates of SMRs; however, the I2 statistic indicated that data were heterogeneous in many of our analyses and therefore these summary measures must be interpreted with appropriate caution. Heterogeneity was not substantially reduced when analyses were stratified by population subgroup (appendix). Insufficient data were available to do subgroup analyses by country.

Table.

Studies included in the standardised all-cause mortality ratio meta-analyses

| Study years | Country | Participants (n) | Population description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homeless people | ||||

| Nielsen et al10 | 1999–2009 | Denmark | 32 711 | Women aged 16 years or older with at least one contact with a homeless shelter |

| Roy et al15 | 1995–2001 | Canada | 829 | Individuals aged 14–25 years with unstable housing |

| Vila-Rodriguez et al16 | 2008–11 | Canada | 293 | Prospective community sample of adults living in single-room occupancy hotel |

| Prisoners | ||||

| Graham et al8 | 1996–2007 | UK | 76 627 | Male individuals imprisoned for the first time between 1996 and 2007 |

| Kariminia et al17 | 1988–2002 | Australia | 85 203 | All adults who had been in full-time custody |

| Individuals with substance use disorders | ||||

| Arendt et al9 | 1996–2006 | Denmark | 20 581 | People receiving treatment in specialist institutions for substance use disorder, who reported cocaine as their primary substance |

| Bargagli et al18 | 1996–2002 | Netherlands | 2575 | Male opiate users aged 15–69 years entering treatment |

| Barrio et al19 | 2004–06 | Spain | 714 | Regular cocaine users recruited from drug scenes and non-treatment settings |

| Bjornaas et al20 | 1980–2000 | Norway | 185 | Individuals with opioid addiction admitted to hospital because of self-poisoning |

| Darke et al21 | 2001–09 | Australia | 615 | Opioid users |

| Degenhardt et al22 | 1985–2005 | Australia | 43 789 | People who are opioid-dependent treated with opioid substitution therapy |

| Evans et al23 | 2005–07 | USA | 644 | Injecting drug users younger than 30 years |

| Gibson et al24 | 1980–2006 | Australia | 2489 | Opioid users |

| Hser et al25 | 2000–02 | USA | 4447 | Women who were admitted to drug treatment programmes |

| Lee et al26 | 2006–08 | Taiwan | 10 842 | Heroin users attending opioid substitution therapy |

| Mathers et al27 | 1980–99 | Denmark | 101 | People who injected opioids and other drugs |

| Merrall et al28 | 1996–2006 | UK | 69 456 | People in contact with drug treatment services |

| Nyhlen et al29, 30 | 1970–2006 | Sweden | 561 | Substance abusers admitted for inpatient detoxification |

| Pavarin et al31 | 1988–2012 | Italy | 471 | Individuals who had visited a public treatment centre for problems due to cocaine use |

| Rehm et al32 | 1994–2000 | Switzerland | 6281 | Participants in heroin-assisted treatment |

| Rosca et al33 | 1999–2008 | Israel | 9818 | Patients who had ever been treated or were currently in treatment in methadone maintenance treatment clinics |

| Singleton et al34 | 1997–2002 | Czech Republic | 3039 | Drug users admitted to hospital for drug-related problems |

| Spittal et al35 | 1996–2002 | Canada | 520 | Injecting drug users recruited through self-referral and street outreach |

| Stoove et al36 | 1990–2006 | Australia | 220 | Injecting drug users recruited from the community |

| van Santen et al37 | 1985–2012 | Netherlands | 1254 | Individuals recruited from local methadone outposts, a sexually transmitted diseases clinic, and by word of mouth |

| Zabransky et al38 | 1996–2008 | Czech Republic | 151 | Injecting drug users aged 15–18 years |

| Degenhardt et al39 | 1996–2004 | Canada | 717 | People who injected cocaine daily |

| Degenhardt et al40 | 1985–2006 | Australia | 42 676 | Opioid users |

Figure 3.

Forest plots of SMRs for all-cause mortality

Data are presented for male individuals (A), female individuals (B), and overall (C). Weights were assigned by random effects analysis. Several studies contribute multiple rows of data because different populations with substance use disorders were studied,9, 31 because different countries were included,18 or because different time periods were studied.28 SMR=standardised mortality ratio. SUD=substance use disorder.

Summary SMRs were higher in female individuals than in male individuals for mortality in each of the ICD-10 categories (appendix pp 6–7). In some ICD-10 categories, the summary SMRs for both sexes combined did not fall between the male and female estimates because the meta-analyses used data from different studies (rather than the estimate for both sexes combined being drawn from the male and female populations).

We identified 201 papers reporting outcomes for infectious and parasitic diseases. Summary estimates of SMRs for infectious diseases were increased in male individuals (2·83 [95% CI 1·61–4·05]; I2=65·4%; appendix p 6) and female individuals (5·58 [1·46–9·70]; I2=60·0%; appendix p 6) and both sexes combined (11·43 [6·91–15·94; I2=97·0%; appendix p 6). Disease prevalence was high but heterogeneous and ranged from 0%41 to 54% for HIV infection,42 from less than 0·1%43 to 90%42 for hepatitis C, from 2% (two of 119)44 to 65% (67 of 103)45 for hepatitis B, and from 1% (one of 82)46 to 51% (133 of 263)47 for latent tuberculosis infection.

Summary estimates of SMRs for injury, poisoning, and other external causes were the highest across all of the ICD-10 categories, in male individuals (7·89 [95% CI 6·40–9·37]; I2=98·1%; appendix p 7), female individuals (18·72 [13·73–23·71]; I2=91·5%; appendix p 7), and both sexes combined (23·53 [15·34–31·71]; I2=99·6%; appendix p 7). However, these categories only accounted for 98 (3%) of 2835 extracted datapoints. Summary SMR estimates were also increased for external causes of morbidity and mortality in male individuals (6·52 [95% CI 5·54–7·51; I2=97·4%; appendix p 7), female individuals (13·15 [9·87–16·43]; I2=93·7%; appendix p 7), and both sexes combined (8·50 [6·89–10·10]; I2=97·5%; appendix p 7). No data from studies that included sex workers were used in any of the SMR estimates for injuries or external causes.

SMRs for mental and behavioural disorders for male individuals and female individuals were exclusively from prison populations and data for both sexes combined were from populations with substance use disorders only. Only two studies included data on male individuals, one study on female individuals, and two studies on both sexes combined. Prevalence of major depression in inclusion health populations ranged from 3% (one of 38 individuals)48 in the month before assessment to a 53% (25 of 47 individuals)49 lifetime prevalence. Prevalence of schizophrenia ranged from 0·9% (212 of 23 530 individuals; we estimated the numerator on the basis of data in the original article)50 to 4% (nine of 227 individuals),51 and from 0% (none of 53 individuals)49 to 45% (221 of 495 individuals; numerator estimated)52 for bipolar disorder.

Summary estimates of SMRs for neoplasms were increased in male individuals (1·61 [95% CI 1·30–1·92]; I2=88·7%; appendix p 6), female individuals (1·91 [1·33–2·49]; I2=62·8%; appendix p 6), and both sexes combined (2·20 [1·61–2·79]; I2=90·6%; appendix p 6). Only 44 studies reported cardiovascular outcomes, accounting for 149 (5%) of 2835 datapoints extracted for this Article. Summary SMRs for diseases of the circulatory system were increased in male individuals (2·44 [95% CI 1·48–3·41]; I2=94·5%; appendix p 6), female individuals (3·13 [1·75–4·52]; I2=51·5%; appendix p 6), and both sexes combined (2·91 [2·04–3·77]; I2=85·8%; appendix p 6). The prevalence of coronary artery disease was 13% (32 of 247 individuals).53 Standardised mortality ratios for respiratory diseases were only reported for populations with substance use disorders and prison populations, ranging from 1·8 (95% CI 1·5–2·1)8 in male Scottish prisoners to 7·9 (5·1–11·8) in populations with substance use disorders in Australia.22 The prevalence of asthma ranged from 5·0% (10 525 of 210 501 individuals; numerator estimated)54 to 26% (nine of 35 individuals).55 Summary SMRs for gastrointestinal conditions included only data from prison populations and populations of individuals with substance use disorders, and were higher in female individuals (7·89 [95% CI 5·81–9·97]; I2=66·1%; appendix p 6) than male individuals (3·37 [2·58–4·15]; I2=93·1%; appendix p 6).

Discussion

The excess mortality associated with considerable social exclusion is extreme. We found all-cause mortality SMRs of 7·9 in male individuals and 11·9 in female individuals. By comparison, mortality rates for individuals aged 15–64 years in the most deprived areas of England and Wales are 2·8 times higher than those in the least deprived areas for male individuals and 2·1 times higher for female individuals.56 The relative excesses were greatest for injury, poisoning, and external causes, but extend across almost all health conditions and across the inclusion health populations that we studied.

The available body of evidence is largest for infectious diseases, with a substantial amount of existing research on morbidity associated with mental and behavioural disorders. By contrast, evidence on non-communicable diseases and injury, poisoning, and external causes is scarce despite these causes having the highest SMRs across ICD-10 categories in our study. SMRs across disease categories were consistently higher in female than male individuals. Of the four inclusion health populations considered, sex workers were the least well investigated, which should be addressed as a matter of priority in future research.

Our study comprehensively describes for the first time, to our knowledge, the relative mortality and morbidity burden in selected inclusion health populations. We have reviewed the existing literature in this area using a comprehensive search strategy to identify the balance of evidence available to inform policy making around inclusion health. Data were extracted and reviewed by a second author to reduce the likelihood of errors. Our approach enabled the identification of relative gaps in both categories of disease and inclusion health categories. Our analysis was informed by an intersectionality perspective, which focuses on how social characteristics in combination affect health.7, 57 We have therefore specifically investigated how the health consequences of exclusion might vary as a result of other socially influenced characteristics, with differences between sexes being particularly noteworthy.

However, several limitations should be considered. Caution must be taken when interpreting the summary estimates because of the heterogeneity of studies. The absence of internationally agreed definitions of inclusion health groups is likely to explain some of this variation. Similarly, comparison groups varied, with some studies using the general population and others using groups living in socially deprived areas. Studies also varied according to the extent of adjustment for social deprivation and other risk factors. We used a random-effects method and noted the recommendations58 that meta-analyses should be pursued whenever possible, acknowledging heterogeneity. We limited our search to articles published from 2005 onwards and therefore we have not examined longer-term trends. Furthermore, for pragmatic reasons, we were unable to investigate other health inclusion groups and believe that further work is needed to describe their health experiences.

We found that the SMRs were consistently higher for female than male individuals. Because general population mortality rates are lower in female individuals than male individuals for most conditions, this result does not necessarily indicate that outcomes were worse in female inclusion health groups than in male groups. These results might reflect an increased vulnerability of women in inclusion health populations or different risk distributions among female individuals and male individuals in inclusion health groups. SMRs are a relative measure, and the lower (but still greater than 1) SMRs for more common diseases such as cardiovascular disease and cancer than for other conditions might underplay the number of excess cases of mortality that occurred as a result of these conditions. Conversely, high SMRs might not indicate a large number of excess deaths if the condition is rare. Further work should report absolute as well as relative measures of mortality.

These extreme inequities demand an intensive cross-sectoral policy and service response to prevent exclusion and improve health outcomes. An accompanying Review,1 published in The Lancet outlines interventions that respond to these increases in morbidity and mortality.

Determining the burden of disease remains challenging in inclusion health populations because membership of such populations is not recorded in most vital registration and health information systems. Deaths and health service use in excluded populations are therefore largely invisible and neglected aspects of routine statistics. By contrast, the availability of area-based measures of social deprivation across high-income countries has allowed the impact of less extreme social inequalities to be measured at the major population level. The outcomes of these measurements have supported extensive cross-sectoral policy initiatives to address these inequities.59 Better routine data is also needed to drive the policy response to the inclusion health agenda.

Two broad potential approaches are available to address this problem. First, health services could routinely record membership of health inclusion groups. This would require agreed definitions of each group. Individuals responsible for recording data would need guidance to help them ascertain membership and avoid reinforcement of stigma.60 The feasibility of this approach outside of specialist services remains unclear. Alternatively, and more feasibly in the short term, data linkage methods could be used to match data from services that work with inclusion health groups, with vital registration data, electronic health records, and existing disease surveillance systems.61 Data linkage has been the primary method used to estimate SMRs in the studies reported in this Article. These linked datasets would facilitate systematic estimates of mortality and morbidity over time and help to measure the effect of interventions.

To inform the content of this Article and the accompanying Review1 we held an engagement workshop with 16 people with experience of homelessness and social exclusion. We asked this group about their views on collecting operational data with ethical and appropriate research governance approvals, but without specific individual level consent. Although this sample was only small (and we acknowledge that people who face exclusion and are willing to attend a workshop might differ from those who do not), acceptability of collection of this sort of data was extremely high. 13 (100%) of 13 participants were happy for homeless hostel records to be collected, eight (73%) of 11 agreed to the collection of criminal records, eight (62%) of 13 to health records, and 11 (85%) of 13 to these records being linked together.

A vertical approach to tackling inclusion health (ie, one that focuses on specific diseases or specific risk groups) can overlook multimorbidity and the social issues faced by excluded populations.62 This approach can result in inefficiencies and missed opportunities for prevention, early diagnosis, and management, and missed opportunities for mitigation of social risk factors. The emerging field of inclusion health should advocate for and deliver joined up health and social services for overlapping marginalised groups. These services should address not only diseases with extreme disparities, but also prevention and management of more common conditions with a lower relative risk but high excess mortality, such as cardiovascular disease. The ability of health and social policy to address the needs of the most marginalised populations should be a key indicator of quality. Such initiatives need to be supported by information systems that can provide data for continuing advocacy, guide service development, and monitor the health of marginalised populations over time.

Our study highlights an extreme health inequity that persists in high-income countries. An inclusion health policy response must build on the evidence regarding who is at risk and the events that trigger exclusion to highlight the social and economic benefits of sustained action to prevent social exclusion.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

RWA was supported by an academic clinical lectureship from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and and a Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Career Development Fellowship (206602/Z/17/Z). AS is funded by University College London Hospitals Foundation Trust. ACH's salary is provided by Central and North West London National Health Service (NHS) Community Trust. EJT and SVK are funded by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12017/13 & MC_UU_12017/15) and the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU13 & SPHSU15). SVK is also funded by a National Research Service (NHS) Research Scotland Scottish Senior Clinical Fellowship (SCAF/15/02). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of The Wellcome Trust, NIHR, NHS, NHS Research Scotland, Medical Research Council, or the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office.

Contributors

RWA, ACH, and AS proposed the hypothesis and idea for the systematic review with all authors contributing to its development and the analysis plan. RWA did the literature search and reviewed studies for inclusion. All authors extracted and checked the data. RWA and DL did all meta-analyses and RWA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and interpreted the results and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

AS is the clinical lead and manager of the Find & Treat service (University College Hospitals NHS Trust). ACH is a trustee of Pathway, a charity for homeless people. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Luchenski S, Maguire N, Aldridge RW. What works in inclusion health: overview of effective interventions for marginalised and excluded populations. Lancet. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31959-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31959-1 published online Nov 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bramley G, Fitzpatrick S, Edwards J. Hard edges: mapping severe and multiple disadvantage in England. 2015. http://lankellychase.org.uk/multiple-disadvantage/publications/hard-edges/ (accessed Dec 2, 2016).

- 3.Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H. Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction. 2006;101:181–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilchrist G, Singleton N, Donmall M, Jones A. Prevalence and factors associated with sex trading in the year prior to entering treatment for drug misuse in England. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;152:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Homelessness in the state and federal prison population. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2008;18:88–103. doi: 10.1002/cbm.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croxford S, Platt L, Hope VD, Cullen KJ, Parry JV, Ncube F. Sex work amongst people who inject drugs in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: findings from a national survey of health harms and behaviours. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:429–433. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzpatrick S, Bramley G, Johnsen S. Pathways into multiple exclusion homelessness in seven UK cities. Urban Stud. 2013;50:148–168. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham L, Fischbacher CM, Stockton D, Fraser A, Fleming M, Greig K. Understanding extreme mortality among prisoners: a national cohort study in Scotland using data linkage. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:879–885. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arendt M, Munk-Jørgensen P, Sher L, Jensen SO. Mortality among individuals with cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine, MDMA, and opioid use disorders: a nationwide follow-up study of Danish substance users in treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;114:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen SF, Hjorthøj CR, Erlangsen A, Nordentoft M. Psychiatric disorders and mortality among people in homeless shelters in Denmark: a nationwide register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:2205–2214. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60747-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peace R. Social exclusion: a concept in need of definition? Soc Policy J N Z. 2001;16:17–36. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzpatrick S, Bramley G, Johnse S. Multiple exclusion homelessness in the UK: an overview of key findings. 2012. http://mcnevaluation.co.uk/download/public/observatory/resource-type/research-evaluation/2012%20Multiple%20Exclusion%20Homelessness%20-%20breifing%20paper%201.pdf (accessed Dec 2, 2016)

- 13.The World Bank World Bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed Nov 2, 2016).

- 14.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy É, Haley N, Boudreau J-F, Leclerc P, Boivin J-F. The challenge of understanding mortality changes among street youth. J Urban Health. 2010;87:95–101. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vila-Rodriguez F, Panenka WJ, Lang DJ. The hotel study: multimorbidity in a community sample living in marginal housing. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1413–1422. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12111439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kariminia A, Butler TG, Corben SP. Extreme cause-specific mortality in a cohort of adult prisoners—1988 to 2002: a data-linkage study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:310–316. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bargagli AM, Hickman M, Davoli M. Drug-related mortality and its impact on adult mortality in eight European countries. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16:198–202. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrio G, Molist G, de la Fuente L. Mortality in a cohort of young primary cocaine users: controlling the effect of the riskiest drug-use behaviors. Addict Behav. 2013;38:1601–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjornaas MA, Bekken AS, Ojlert A. A 20-year prospective study of mortality and causes of death among hospitalized opioid addicts in Oslo. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darke S, Mills KL, Ross J, Teesson M. Rates and correlates of mortality amongst heroin users: findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS), 2001–2009. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degenhardt L, Larney S, Randall D, Burns L, Hall W. Causes of death in a cohort treated for opioid dependence between 1985 and 2005. Addiction. 2014;109:90–99. doi: 10.1111/add.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans JL, Tsui JI, Hahn JA, Davidson PJ, Lum PJ, Page K. Mortality among young injection drug users in San Francisco: a 10-year follow-up of the UFO study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:302–308. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson A, Randall D, Degenhardt L. The increasing mortality burden of liver disease among opioid-dependent people: cohort study. Addiction. 2011;106:2186–2192. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hser YI, Kagihara J, Huang D, Evans E, Messina N. Mortality among substance-using mothers in California: a 10-year prospective study. Addiction. 2012;107:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee CTC, Chen VCH, Tan HKL. Suicide and other-cause mortality among heroin users in Taiwan: a prospective study. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2619–2623. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Lemon J, Wiessing L, Hickman M. Mortality among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:102–123. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.108282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrall ELC, Bird SM, Hutchinson SJ. Mortality of those who attended drug services in Scotland 1996–2006: record-linkage study. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nyhlen A, Fridell M, Hesse M, Krantz P. Causes of premature mortality in Swedish drug abusers: a prospective longitudinal study 1970–2006. J Forensic Leg Med. 2011;18:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyhlen A, Fridell M, Backstrom M, Hesse M, Krantz P. Substance abuse and psychiatric co-morbidity as predictors of premature mortality in Swedish drug abusers a prospective longitudinal study 1970–2006. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavarin RM. Mortality risk for cocaine abusers in relation to heroin use: a follow-up study. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48:702–710. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.786731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rehm J, Frick U, Hartwig C, Gutzwiller F, Gschwend P, Uchtenhagen A. Mortality in heroin-assisted treatment in Switzerland 1994–2000. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosca P, Haklai Z, Goldberger N, Zohar P, Margolis A, Ponizovsky AM. Mortality and causes of death among users of methadone maintenance treatment in Israel, 1999–2008. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125:160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singleton J, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Zabransky T. Mortality among amphetamine users: a systematic review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spittal PM, Hogg RS, Li K. Drastic elevations in mortality among female injection drug users in a Canadian setting. AIDS Care. 2006;18:101–108. doi: 10.1080/09540120500159292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoové MA, Dietze PM, Aitken CK, Jolley D. Mortality among injecting drug users in Melbourne: a 16-year follow-up of the Victorian Injecting Cohort Study (VICS) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Santen DK, van der Helm JJ, Grady BPX. Temporal trends in mortality among people who use drugs compared with the general Dutch population differ by hepatitis C virus and HIV infection status. AIDS. 2014;28:2589–2599. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zabransky T, Csemy L, Grohmannova K, Janikova B, Brenza J. Mortality of cohort of very young injecting drug users in Prague, 1996–2010. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2011;19:152–157. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Degenhardt L, Singleton J, Calabria B. Mortality among cocaine users: a systematic review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Degenhardt L, Randall D, Hall W, Law M, Butler T, Burns L. Mortality among clients of a state-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: risk factors and lives saved. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilles M, Swingler E, Craven C, Larson A. Prison health and public health responses at a regional prison in Western Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32:549–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Des Jarlais DC, Perlis T, Arasteh K. Reductions in hepatitis C virus and HIV infections among injecting drug users in New York City, 1990–2001. AIDS. 2005;19(suppl 3):S20–S25. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000192066.86410.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.del Amo J, González C, Losana J. Influence of age and geographical origin in the prevalence of high risk human papillomavirus in migrant female sex workers in Spain. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:79–84. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.008060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Havens JR, Walker R, Leukefeld CG. Prevalence of opioid analgesic injection among rural nonmedical opioid analgesic users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bart G, Piccolo P, Zhang L, Jacobson I, Schaefer RA, Kreek MJ. Markers for hepatitis A, B and C in methadone maintained patients: an unexpectedly high co-infection with silent hepatitis B. Addiction. 2008;103:681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carbonara S, Babudieri S, Longo B. Correlates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a prison population. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:1070–1076. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00098104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabuchi T, Takatorige T, Hirayama Y. Tuberculosis infection among homeless persons and caregivers in a high-tuberculosis-prevalence area in Japan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prinsloo B, Parr C, Fenton J. Mental illness among the homeless: prevalence study in a Dublin homeless hostel. Ir J Psychol Med. 2012;29:22–26. doi: 10.1017/S0790966700017560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lubman DI, Allen NB, Rogers N, Cementon E, Bonomo Y. The impact of co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders among substance-abusing youth. J Affect Disord. 2007;103:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baillargeon J, Penn JV, Thomas CR, Temple JR, Baillargeon G, Murray OJ. Psychiatric disorders and suicide in the nation's largest state prison system. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37:188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vergara-Moragues E, González-Saiz F, Lozano OM. Psychiatric comorbidity in cocaine users treated in therapeutic community: substance-induced versus independent disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Darke S, Williamson A, Ross J, Teesson M. Attempted suicide among heroin users: 12-month outcomes from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown RT, Kiely DK, Bharel M, Mitchell SL. Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:16–22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1848-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harzke AJ, Baillargeon JG, Pruitt SL, Pulvino JS, Paar DP, Kelley MF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among inmates in the Texas prison system. J Urban Health. 2010;87:486–503. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9448-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Brien KK, Schuttke A, Alhakeem A. Health, perceived quality of life and health services use among homeless illicit drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romeri E, Baker A, Griffiths C. Mortality by deprivation and cause of death in England and Wales, 1999–2003. Health Stat Q. 2006;32:19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kapilashrami A, Hill S, Meer N. What can health inequalities researchers learn from an intersectionality perspective? Understanding social dynamics with an inter-categorical approach? Soc Theory Health. 2015;13:288–307. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ioannidis JPA, Patsopoulos NA, Rothstein HR. Reasons or excuses for avoiding meta-analysis in forest plots. BMJ. 2008;336:1413–1415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marmot M. Fair society, healthy lives: the Marmot Review: strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. 2010. https://www.gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review-strategic-review-of-health-inequalities-in-england-post-2010 (accessed Oct 22, 2017).

- 60.Katikireddi SV, Valles SA. Coupled ethical-epistemic analysis of public health research and practice: categorizing variables to improve population health and equity. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e36–e42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aldridge RW, Shaji K, Hayward AC, Abubakar I. Accuracy of probabilistic linkage using the enhanced matching system for public health and epidemiological studies. PloS One. 2015;10:e0136179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380:37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.