Abstract

Background

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subcallosal cingulate (SCC) is an emerging experimental therapy for treatment-resistant depression. New developments in SCC DBS surgical targeting are focused on identifying specific axonal pathways for stimulation that are estimated from preoperatively collected diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) data. However, brain shift induced by opening burr holes in the skull may alter the position of the target pathways.

Objectives

Quantify the effect of electrode location deviations on tractographic representations for stimulating the target pathways using longitudinal clinical imaging datasets.

Methods

Preoperative MRI and DWI data (planned) were coregistered with postoperative MRI (1 day, near-term) and CT (3 weeks, long-term) data. Brain shift was measured with anatomical control points. Electrode models corresponding to the planned, near-term, and long-term locations were defined in each hemisphere of 15 patients. Tractography analyses were performed using estimated stimulation volumes as seeds centered on the different electrode positions.

Results

Mean brain shift of 2.2 mm was observed in the near-term for the frontal pole, which resolved in the long-term. However, electrode displacements from the planned stereotactic target location were observed in the anterior-superior direction in both the near-term (mean left electrode shift: 0.43 mm, mean right electrode shift: 0.99 mm) and long-term (mean left electrode shift: 1.02 mm, mean right electrode shift: 1.47 mm). DBS electrodes implanted in the right hemisphere (second-side operated) were more displaced from the plan than those in the left hemisphere. These displacements resulted in 3.6% decrease in pathway activation between the electrode and the ventral striatum, but 2.7% increase in the frontal pole connection, compared to the plan. Remitters from six-month chronic stimulation had less variance in pathway activation patterns than the non-remitters.

Conclusions

Brain shift is an important concern for SCC DBS surgical targeting and can impact connectomic analyses.

Keywords: Connectomic, Electrode, Neurosurgery, Stereotactic, Tractography

Introduction

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subcallosal cingulate (SCC) is an emerging experimental therapy for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) [1,2]; however, the therapeutic target of the stimulation remains under investigation. Recent attempts to identify the surgical target for SCC DBS have focused on axonal pathways in the SCC region, given their greater relative electrical excitability compared to other neural tissues [3]. Anatomical tract tracing studies [4] and gross dissection [5] have identified a wide range of white matter (WM) pathways that might be associated with the therapy. In the context of human SCC DBS patients, some of those pathways can be noninvasively estimated using tractography derived from diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) [6–8]. Tractography-based pathway estimates can then be coupled to electrical models of DBS to simulate axonal activation during therapy delivery [9]. The concepts of DBS model predicted pathway activation have been retrospectively applied to the analysis of a large number of patients and showed that direct stimulation of four WM pathways (forceps minor, uncinate fasciculus, cingulum bundle, and fronto-striatal fibers) are critical for efficacy [10] and behavioral response to SCC DBS [11]. Based on these finding, prospective patient-specific surgical targeting for SCC DBS electrode placement has recently evolved to use a “tractography blueprint” [10]. This new connectomic targeting approach has shown promise for improving clinical outcomes from SCC DBS [12]. However, brain shift is a known issue in DBS surgical procedures and it is unknown how brain shift might impact the accuracy of connectomic targeting strategies.

Independent of the surgical target or clinical therapy under consideration, the accuracy of DBS electrode placement is widely acknowledged to be a key determinant of clinical response. Unfortunately, numerous factors combine to limit DBS surgical accuracy including ambiguous definition of the target, lack of optimal imaging methods to visualize the target, and mechanical tolerance of stereotaxis. In addition, direct DBS targeting methods commonly assume that the brain does not move relative to the skull. However, numerous clinical studies have documented that brain shift does occur during DBS surgery [13–16]. Brain shift results from a range of factors that can include: loss of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), intracranial pressure drop, gravitational forces, and pressures created by pneumocephalus. These factors can alter the actual location of the preoperatively defined surgical target [17–19]. The magnitude of brain shift can range from 0–10 mm throughout the entire brain, but is typically only on the order of 0.5–1.0 mm in the basal ganglia where most DBS electrodes are placed. However, prefrontal cortical structures commonly deflect by several millimeters and these larger shifts in the more anterior aspects of the brain may have important implications for SCC DBS targeting.

The goal of this study was to quantitatively evaluate the magnitude and direction of brain shift that occurs during SCC DBS surgery. We analyzed this problem using an extensive database of imaging datasets acquired at multiple time points along the course of SCC DBS therapy in 15 patients. In addition, we evaluated how the variance in electrode position impacted the pathway activation predictions used in the new SCC “tractography blueprint” connectomic targeting method.

Material and Methods

This study combines a unique patient population with extensive imaging datasets that includes preoperative and postoperative MRI, as well as postoperative CT, each acquired at different time points in the therapy. The images were integrated together within a custom software tool, StimVision [20], to evaluate changes within the context of the stereotactic neurosurgical coordinate system. Our goal was to quantify the variance between the preoperatively planned electrode placement, the near-term postoperative placement, and the actual long-term postoperative location.

Ethics statement

The collection and analysis of all patient data used for this study was approved by the Emory University IRB and conducted under FDA IDE: G060028 and G130107.

SCC DBS subjects

Fifteen patients with severe, chronic TRD from two consecutive DBS study cohorts underwent stereotactic implantation of bilateral electrodes (Cohort 1 (n = 9): Libra system, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott Neuromodulation, St. Paul, MN), and Cohort 2 (n = 6): Activa PC+S with 3387 electrodes, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) into the SCC region. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in a previously published study [21]. Patients were required to be depressed for at least 12 months in the current depressive episode with a minimum Hamilton Depression Rating Scale severity (HDRS-17) of 20, failed at least 4 antidepressant treatments, and have no significant psychiatric comorbidities (Table 1). Clinical outcome was assessed after 24 weeks of stimulation using the HDRS-17. Remission from their depression symptoms was defined as a score of 7 or less on the HDRS-17 at 24 weeks.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of treatment-resistant depression patients, and operation time for bilateral implantation of electrodes.

| Characteristics | Patients with TRD |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 50.06 (10.31) |

| Gender, Female/Male | 11/4 |

| HDRS-17 at surgery, mean (SD) | 22.3 (2.33) |

| Age onset of MDD, mean (SD) | 25.67(11.28) |

| Lifetime number of MDD episode, mean (SD) | 3.53 (1.4) |

| Duration of current episode (months), mean (SD) | 38.33(31.29) |

| Remitter (HDRS-17 ≤ 7)/Nonremitter at 24 weeks | 7/8 |

| Total operation time (minutes), mean (SD) | 513.8(93.2) |

Abbreviations: HDRS-17 – 17 Item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MDD – Major Depressive Disorder; TRD – Treatment Resistant Depression

The combination of tractography and anatomical image-guided stereotactic targeting methods [10,11] were used to identify the preoperative surgical target location. Lead implantation was performed using a CRW stereotactic frame system (Integra, Plainsboro, NJ) and assisted by a surgical planning workstation (SteathStation S7, Medtronic Inc., Louisville, CO). To minimize cerebrospinal fluid leaks, the fibrin sealant TISSEEL was applied in the burr hole. The left electrode was always implanted first. Mean operation time for bilateral implantation of SCC DBS was 513.8 ± 93.2 minutes.

Imaging data acquisitions

Preoperative MRI data were collected using a research-dedicated Siemens 3-Tesla Trio Tim scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA) with maximum gradient strength of 40 mT/m at Emory University. High-resolution structural 3D T1-weighted images were acquired using magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo imaging (MPRAGE) sequence with following parameters: 176 slices, 1×1×1 mm3, TR/TE = 2600ms/3.02ms, flip angle = 8°. Two different DWI protocols were used to generate the data used in this study. The SJM patients (Cohort 1) were imaged using a single-shot spin-echo planar sequence (n = 9) with 12-channel head coil using the following parameters: 60 non-collinear directions with four non-diffusion weighted images (b=0); b value = 1000 sec/mm2; voxel resolution = 2×2×2 mm3; number of slices = 64; matrix = 128 × 128; TR/TE = 11300/90 ms. The MDT patients (Cohort 2) were imaged using a multi-band accelerated echo planar sequence (n = 6) with 32-channel coil using following parameters: 128 non-collinear directions with 11 non-diffusion weighted images (b=0); b value = 1000 sec/mm2; voxel resolution = 2×2×2 mm3; number of slices = 64; matrix = 128 × 128; TR/TE = 3292/96 ms; multi-band acceleration factor = 3 [22]. To compensate for susceptibility-induced distortion artifacts, all diffusion data were acquired twice with two opposite phase encoding directions such as anterior to posterior and posterior to anterior [23].

Preoperative stereotactic frame structural 3D T1-weighted MPRAGE images were collected in all subjects using a 1.5-Tesla Siemens Magnetom Avanto scanner with Luminant localizer frame (CRW systems, Intergra) for surgical planning on the morning of surgery: 176 slices; 1×1×1 mm3; TR/TE = 1910ms/3.51ms, flip angle = 15°. Postoperative MRI (near-term) and CT (long-term) images were collected one day and three weeks after the surgery, respectively, to calculate the brain shift and identify electrode location. Postoperative structural 3D T1-weighted MPRAGE images were acquired using the same imaging protocol as the preoperative frame image. High-resolution CT images were collected using Speed light GE with resolution of 0.46×0.46×0.65 mm3.

Imaging data processing

Both preoperative and postoperative structural T1-weighted images were preprocessed using FSL_anat tool in FMRIB Software Library (FSL) (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/) for skull stripping, RF/B1 inhomogeneity correction, tissue-type segmentation, and registration to standard space [24]. DWI data underwent simultaneous eddy current and motion collection with Topup and Eddy tools to compensate eddy current-induced distortion and subject movements [25,26]. Preprocessed DWI data were loaded into TrackVis (TravkVis.org) software for deterministic tractography and Fdt toolkit (FMRIB Software Library) for probabilistic tractography analysis [24,27].

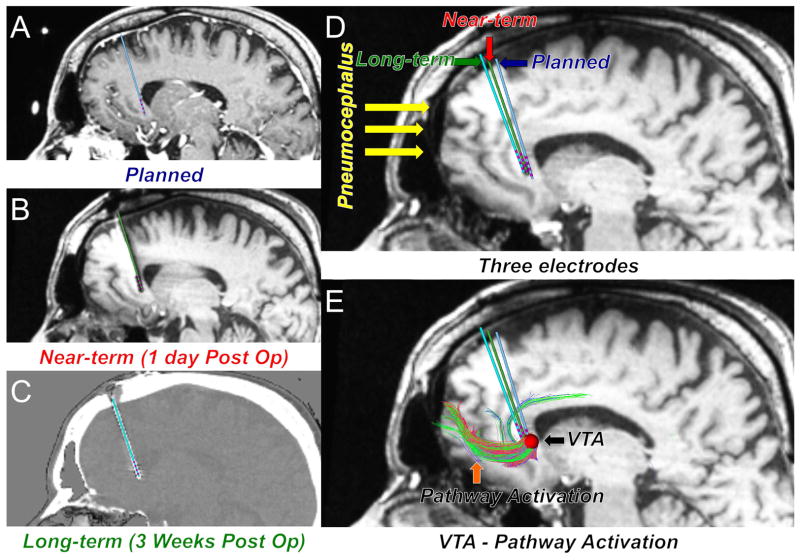

All imaging data were aligned to the stereotactic frame structural T1-weighted image to assess brain shift. An affine linear registration method (3dAllineate tool, AFNI: https://afni.nimh.nih.gov) was used for alignment with following parameters: degree of freedom = 9 and normalized mutual information [28]. The aligned images were visually inspected and loaded into StimVision software for quantitative brain shift analysis and visualization (Figure 1) [20].

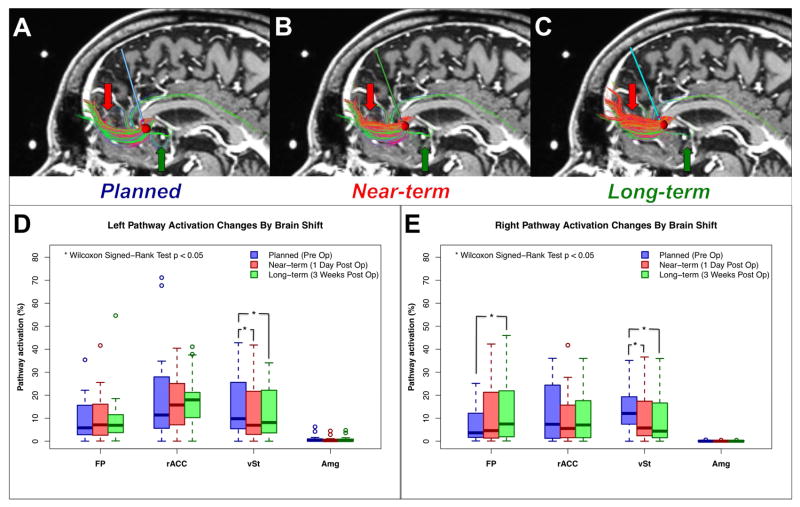

Figure 1.

Quantitative analysis and visualization of brain shift with extensive imaging datasets using patient-specific electrode modeling and pathway activation prediction (StimVision) in subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation. Three electrodes indicate the preoperative targeting location (A) Planned: Blue, 1-day postoperative location (B) Near-term: Red, and 3-weeks postoperative location (C) Long-term: Green. D) Three electrodes are shown on the 1-day postoperative image with pneumocephalus. E) A volume of tissue activated (VTA) and the pathways passing through the VTA are displayed on the 1-day postoperative image. The VTA was generated with the following stimulation parameters: monopolar, 130Hz, 90μsec, 6mA.

Imaging data analysis

The 3D coordinates of three control points--the anterior commissure (AC), the posterior commissure (PC), and the frontal pole (FP)--were defined independently by two authors (KSC and PRP) on the planned and near-term structural MR images and then averaged. The FP coordinate was selected based on the largest volume of pneumocephalus in the sagittal view of the 3D image regardless of hemisphere. The brain displacement of AC, PC, and FP between planned and near-term images was calculated separately as left – right, anterior – posterior, and superior – inferior.

Any pneumocephalus identified in the postoperative MRI was manually segmented using the FSL view toolkit (FMRIB Software Library). Due to poor tissue contrast in the postoperative CT image (long-term), only the near-term structural MR image was used for evaluating the pneumocephalus volume. Left and right volumes were calculated separately and statistically compared.

Electrode contact displacements along the path of planned, near-term, and long-term trajectories were calculated using StimVision [20]. The 3D coordinates of the chronic stimulation contact (generally the second or third most distal contact), which in all cases was also the contact used to define the planned target point in preoperative targeting, was measured: left – right (x), anterior – posterior (y), and superior – inferior (Z).

An important assumption in new tractography-based DBS surgical targeting strategies is that the target point does not move over the course of the surgery, and/or any brain shift that does occur does not alter the anticipated pathway activation profile. To evaluate the potential impact of this assumption, we performed seed to target probabilistic tractography analyses (probtrackx2, FMRIB Software Library)[24] using electrode locations that corresponded to the planned, near-term, and long-term locations in each hemisphere of each patient. The seed was defined as the volume of tissue activated (VTA) by monopolar stimulation, frequency = 130Hz, pulse width = 90μsec, and current = 6mA from established models [29] available in StimVision [20]. The VTA was centered on the contact on the DBS lead used for chronic stimulation. The 4 probabilistic tractography target ROIs were frontal pole (forceps minor and uncinate fasciculus), ventral striatum (fronto-striatal fibers), rostral anterior cingulate cortex (cingulum bundle), and amygdala (uncinate fasciculus)[10] (target ROIs shown in supplementary figure 1). Five thousand streamlines were sent out from each voxel in each VTA (n = 90, left and right VTAs × 15 subjects × three time points) and the total number of streamlines that intersected each ROI was counted. Lastly, a pathway activation (structural connectivity) connection was calculated using the number of streamlines that connected between the VTA and ROI divided by the total number of streamlines that were sent out from the VTA.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each brain shift measurement. For the statistical comparisons of brain shift at multiple time points, a Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was performed on the anatomical control points, electrode and contact location, and pathway activation connection changes. The correlation between operation time and the extent of brain shift (anatomical shift, pneumocephalus volume, electrode shift, and pathway activation changes) were analyzed using Spearman Rank correlations. The effect of brain shift with clinical outcomes was evaluated by sorting patients into two groups, remitters (HDRS-17 ≤ 7 at 24 weeks) or nonremitters (HDRS-17 > 7 at 24 weeks) [12,21] and differences in mean brain shift measurements were tested with a Mann-Whitney U Test.

Results

Brain shift from SCC DBS surgery was assessed on fifteen subjects at multiple time points in their DBS therapy using various measurements including anatomical control points, pneumocephalus volume, electrode location, and pathway activation changes. Significant brain shift was recorded in the frontal pole, which was accompanied by pneumocephalus, in all near-term images. Displacement of electrode locations from the planned stereotactic target site was observed in the anterior and superior directions on both near-term and long-term images. DBS electrodes implanted in the right hemisphere were generally more displaced than those in the left hemisphere. The long-term tractography-based connectivity between the electrode and the ventral striatum decreased compared to the plan, but increased for the frontal connectivity. We did not find a significant relationship between the operation time and brain shift measurements. However, the pathway activation predictions of the remitters after 24 weeks of DBS showed less variance from the planned pathway activation predictions, for both the near-term and long-term, than the nonremitters.

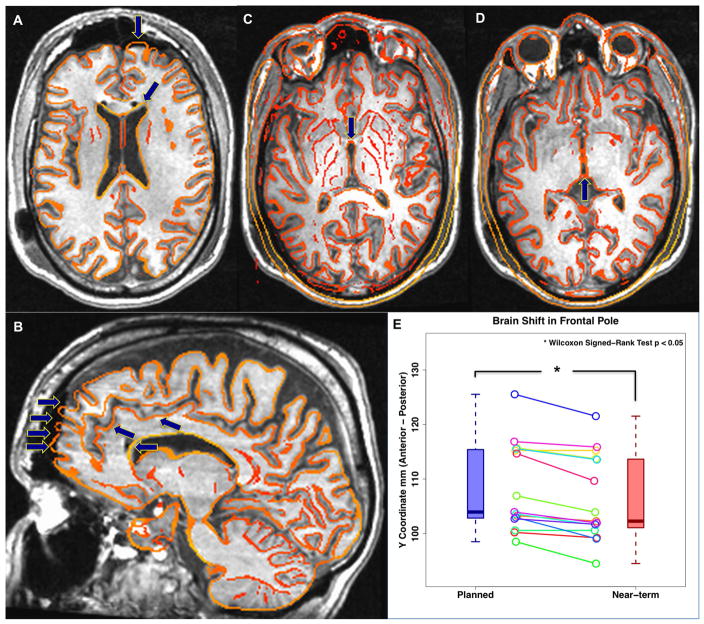

Anatomical control point variance

Three control points (AC, PC, and FP) from each patient were recorded and averaged in the preoperative (planned) and postoperative (near-term) structural images (Figure 2). We did not observe significant brain shift in the AC or PC points (Figure 2. C, D). However, significant brain shift was measured in the FP (Figure 2. E). The direction of the FP brain shift was posterior and inferior, coinciding with expected effects of gravity. The range of FP shift was 0 – 5 mm with an average of 2.2 ± 1.56 mm.

Figure 2.

Brain shift of anatomical control points in subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation. Underlay 1-day postoperative structural image (Near-term) with overlay edge of preoperative structural image (Planned). A–B) Brain shift of the frontal pole (FP) in axial and sagittal view. C–D) Brain shift of the anterior- and posterior-commissure (AC, PC). E) Plot of the brain shift observed for the frontal pole (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test p < 0.05). No significant brain shift was noted at the AC or PC for SCC DBS surgery. However, significant brain shift was measured in FP. The mean brain shift in FP is 2.2 ± 1.56 mm and max displacement was 5mm.

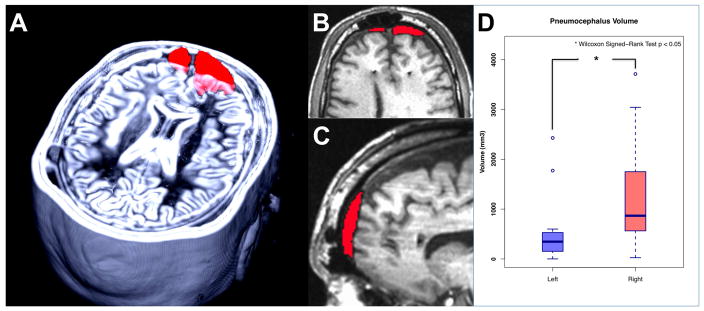

Pneumocephalus volume variance

The pneumocephalus volume was manually segmented and calculated in each subject (Figure 3A–C). The total, left, and right hemisphere volume were recorded separately and compared. The total mean pneumocephalus volume was 1770 ± 1185 mm3. The left and right volumes were 528 ± 679 mm3 and 1239 ± 1101mm3, respectively. The right volume was significantly larger than the left (p < 0.05 Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test) (Figure 3D). Notably, the right side was always the second to be implanted.

Figure 3.

Pneumocephalus volume. A) 3D reconstruction, B) axial view, and C) sagittal view of pneumocephalus volume of one participant. D) Average pneumocephalus volume of left and right hemisphere. The mean pneumocephalus volumes: Total volume = 1770 ± 1185 mm3, Left hemisphere = 528 ± 679 mm3, Right hemisphere = 1239 ± 1101mm3. Right pneumocephalus volume is significantly larger than left hemisphere (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test p < 0.05).

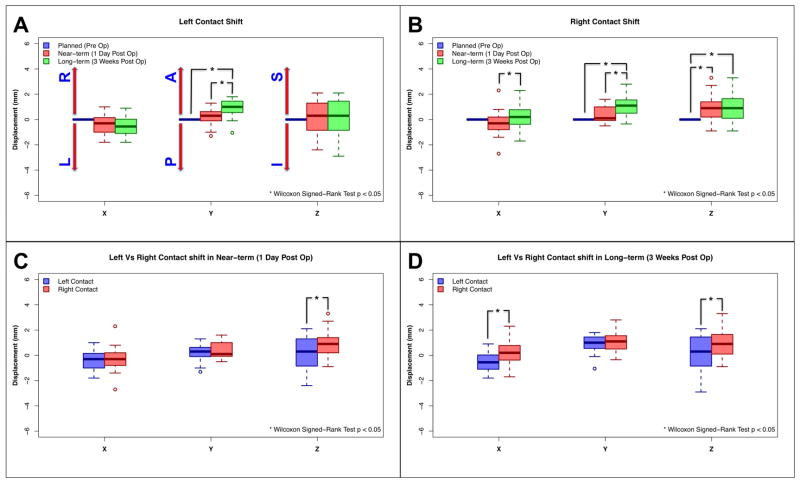

Electrode location variance

The 1-day postoperative (near-term) and 3-weeks postoperative (long-term) electrode locations were compared to the preoperatively targeted (planned) electrode location (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test p < 0.05) and summarized in Table 2. Significant displacement in the anterior direction was observed in the left hemisphere on the long-term images (mean shift = 1.02 mm) relative to both the planned and near-term images (mean shift = 0.43 mm) (Figure 4A). In addition, significant displacement of the electrode in the right, anterior, and superior directions was noted in the right hemisphere in the long-term images (mean shift = 1.47 mm) relative to the right planned and near-term location (mean shift = 0.99 mm) (Figure 4B). The magnitude of electrode displacement relative to the preoperative plan was generally greater in the right hemisphere (second operated side) than in the left hemisphere (Figure 4C, D).

Table 2.

Electrode contact displacements (mm) along the path of planned, near-term, and long-term trajectories. The 1-day postoperative (near-term) and 3-weeks postoperative (long-term) electrode locations were compared to originally targeted (planned) electrode location (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test p < 0.05)

| Hemisphere | Contrast | X (L – R) | Y (P – A) | Z (S – I) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Planned - Near-term |

−0.37(±0.84) | 0.19(±0.73) | 0.13(±0.37) |

| Planned - Long-term |

−0.49(±0.82) | 0.9(±0.75)* | 0.06(±1.61) | |

| Near-term - Long-term |

−0.12(±0.43) | 0.71(±0.59)* | −0.07(±0.49) | |

| Right | Planned - Near-term |

−0.29(±1.12) | 0.37(±0.65) | 0.88(±1.13)* |

| Planned - Long-term |

−0.17(±1.03) | 1.11(±0.85)* | 0.95(±1.25)* | |

| Near-term - Long-term |

0.47(±0.44)* | 0.73(±0.63)* | 0.07(±0.42) |

Abbreviations: X (L – R): Left (−) and Right (+), Y (P – A): Posterior (−) – Anterior (+), Z (S – I): Superior (−) – Inferior (+),

p < 0.05 in Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test

Figure 4.

Electrode displacements. The 1-day postoperative (Near-term: Red) and 3-weeks postoperative (Long-term: Green) electrode locations were compared to the preoperative plan (Planned: Blue) (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test p < 0.05). A) Left electrode displacement, B) Right electrode displacement, C) Left and right comparison in near-term, and D) Left and right comparison in long-term. Significant anterior direction shift was observed in left long-term compared to left planned and near-term. Significant right, anterior, and superior direction shift was observed in right long-term compared to right planned and near-term. Electrode displacement in right hemisphere was significantly higher than left hemisphere in the superior direction for the near-term, and the right and superior directions for the long-term.

Abbreviations; X: Left – Right, Y: Posterior – Anterior, Z: Inferior – Superior, L: Left, R: Right, A: Anterior, P: Posterior, S: Superior, I: Inferior, *: p < 0.05 in Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test.

Pathway activation variance

For visual reference, we examined the pathway activation patterns generated by the VTAs associated with the planned, near-term, and long-term electrode locations using deterministic tractography (Figure 5A–C). For quantitative assessment, we evaluated the changes in pathway activation patterns using probabilistic tractography. We found a significant reduction of pathway activation connection to the ventral striatum in both left and right hemispheres, primarily due to electrode displacement in anterior and superior directions (Figure 5D, E). In contrast, pathway activation connection between the electrode contact and frontal pole was increased at the long-term electrode location relative to the preoperative plan, but only in the right hemisphere (Figure 5E). These displacements resulted in a 3.6% decrease in pathway activation between the electrode and the ventral striatum, but a 2.7% increase in the frontal pole connection, compared to the plan. Despite these variations, the overall pathway activation pattern maintained the intended SCC DBS “tractography blueprint” [10,12] at each of the available time points.

Figure 5.

Changes in pathway activation with brain shift in SCC DBS. Demonstration of pathway activation changes using deterministic tractography in A) Planned electrode location, B) Near-term electrode location, and C) Long-term electrode location. Red arrow indicates an increase of FP connection and Green arrow indicates a reduction of vSt connection. The pathway activation between VTA and each target region of interest (frontal pole: forceps minor and uncinate fasciculus, rostral ACC: cingulum bundle, ventral striatum: fronto-striatal fiber, and amygdala: uncinate fasciculus) was calculated using a probabilistic tractography and compared among planned, near-term, and long-term. D) Comparison of changed in pathway activation with planned (blue), near-term (red), and long-term (green). The pathway activation of the vSt connection was significantly reduced in both left and right hemisphere due to electrode displacement in anterior and superior directions. Significant increases in pathway activation to the FP connection was recorded in right hemisphere for the long-term data. Abbreviations; FP: frontal pole, rACC: rostral anterior cingulate cortex, vSt: ventral striatum, Amg: amygdala, *: p < 0.05 in Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test.

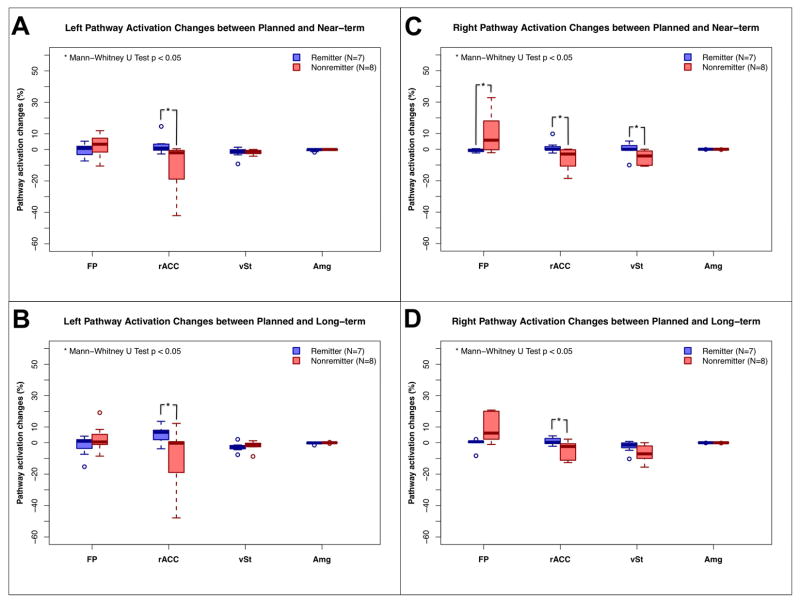

Brain shift and clinical outcomes

We examined the correlation of the operation time with the various brain shift measurements. No significant relationship was found. However, we did find significant differences in the pathway activation changes over time between remitters and nonremitters (Mann-Whitney U Test p < 0.05). Nonremitters had significantly larger net changes in their pathway activation connection in both the near and long term relative to the initial plan. (Figure 6)

Figure 6.

Comparison of changes in the pathway activation between remitters and nonremitters. Remitters (HDRS-17 ≤ 7 at 24 weeks) exhibited significantly less changes in their pathway activation than the nonremitters (Mann-Whitney U test p < 0.05) over the various time points. Abbreviations; FP: frontal pole, rACC: rostral ACC, vSt: ventral striatum, Amg: amygdala, *: p < 0.05 in Mann-Whitney U test.

Discussion

This study quantified the impact of brain shift on SCC DBS therapy, and represents the first brain shift study to focus on a neuropsychiatric DBS target. Given that the most common neuropsychiatric DBS targets are located at the confluence of a combination of multidirectional white matter pathways (e.g. ALIC, MFB, SCC) [1,30–32], we were motivated to determine if such targets are more or less susceptible to brain shift deviations than basal ganglia or other subcortical grey matter DBS targets. We noted five main findings from this study. First, the frontal pole shifted by an average of 2.2 mm in the near-term images. Second, frontal pole shift was confirmed by pneumocephalus volume analysis. Third, we found significant anterior and superior displacement of the electrode, relative to the preoperative plan, which coincided with the anatomical brain shift. Fourth, DBS pathway activation patterns were altered as a consequence of the electrode displacement. Lastly, nonremitters from 24 weeks of chronic stimulation showed significantly greater changes in their DBS pathway activation patterns from their electrode displacements, compared to remitters.

The results of this study highlight an important caveat for the rapidly expanding application of tractography in DBS research. Fundamental assumptions on the stability of a predefined target point in the brain are susceptible to error when faced with the realities of intracranial surgery. Therefore, while connectomic-based scientific analyses and surgical targeting strategies have potential to advance the field and improve outcomes, they are still bound by the basic mechanical and structural limitations of DBS surgical targeting. For example, recent analysis suggests that ~15% of implanted DBS leads for Parkinson’s disease need to be revised due to misplacement [33]. In turn, there is great need to not only improve our ability to identify the target on a patient-specific basis, but also deliver the electrode to that target point with greater accuracy. In attempts to achieve that goal, we have used connectomic analyses to define a novel targeting strategy for SCC DBS [10], and demonstrated that using it can potentially improve outcomes [12]. However, the results of this study show that substantial variance in the procedure remains.

The SCC region is especially well-suited to the application of connectomic-based surgical targeting strategies because the therapeutic electrodes are explicitly located in large white matter pathways. In turn, the inherent limitations of DWI data and tractography analyses [34] are somewhat minimized given the strong anisotropy of the region and robust ability to reconstruct the pathways of interest [7]. As a result, even with the electrode displacements we observed, the pathway activation variance was relatively moderate and still capable of generating the desired clinical effect in most patients [12]. So while brain shift is likely larger in the SCC (~2 mm), compared to the basal ganglia (~1 mm), the relative clinical impact on limiting stimulation of the targeted neural elements appears to be comparable [19].

Brain shift in other neuropsychiatric DBS targets has yet to be assessed. Therefore, it is currently unknown if electrode displacement effects are different for WM targets of different sizes or anatomical complexity (i.e., the medial forebrain bundle [30] versus the anterior limb of the internal capsule [31,32]) or for small gray matter targets adjacent to anterior or posterior midline CSF spaces (i.e., the nucleus accumbens [35,36] and lateral habenula [37]). Regardless of the target, understanding the interaction between brain shift and tractographic mapping for any connectomic targeting strategy is an important consideration for improving surgical precision and maximizing the likelihood of good clinical outcomes.

This study attempted to address potential targeting errors associated with brain shift during SCC DBS surgery. We relied on the largest single institution collection of SCC DBS patients currently available, but the total number of subjects was still relatively small. In addition, we elected to pool data from different studies using different imaging paradigms and different DBS systems. However, we deemed those limitations as acceptable because the fundamental features of brain shift, and the general ability to measure it, should be independent of those issues. For example, we did not see any symmetric differences in brain shift between the two cohorts (SJM and MDT). Nonetheless, numerous technical issues, primarily associated with image registration methods, can introduce unwanted variance into the analysis. Our results are undoubtedly impacted by registration errors, which are typically estimated to be on the order of 1mm [38,39]. In attempts to minimize these errors, we relied on advanced registration algorithms that are commonly used in brain imaging research [28]. However, a potentially bigger issue is our assumption that the pre-operative DWI data is representative of the post-operative state. It is currently unknown how white matter pathways, or their tractographic reconstructions, might move in response to brain shift, or how that movement might resolve with a newly implanted DBS electrode nearby. Such questions highlight the need for future studies addressing brain shift using intraoperative MRI data collection [19], as well as longitudinal documentation of electrode locations at multiple time points over the first few days and/or weeks after surgery.

It should also be noted that the experimental SCC DBS cases analyzed in this study consisted of especially long intraoperative procedures. This was done for behavioral and electrophysiological testing purposes [11]. We acknowledge that shorter procedure times and/or alternative surgical practices (e.g. burr hole size, dura management, cannula placement) could have potentially helped to limit the brain shift we observed. Therefore, if SCC DBS evolves from an experimental procedure to a more common clinical therapy, several procedural alterations could be considered to help compensate for the anticipated brain shift. In addition, the growing availability of more versatile DBS devices that provide directional electrodes and allow for current steering between different contacts, may help attenuate the potential confounds of brain shift on electrode displacement and subsequent impact on therapy optimization.

Conclusions

Significant brain shift during bilateral SCC DBS electrode implantation was observed in the frontal pole, which was associated with larger pneumocephalus volumes, especially on the right hemisphere (second operated side). This brain shift contributed to electrode location displacement in the anterior and superior directions that subsequently resulted in alternations to the DBS pathway activation predictions from the preoperative plan. These results highlight an important caveat when evaluating tractography-based DBS targeting strategies, as brain shift might play a role in limiting the ability to precisely stimulate the targeted pathways of interest.

Supplementary Material

Connectomic deep brain stimulation surgical targeting represents a promising new strategy.

Intraoperative brain shift can alter the location of a tractography defined surgical target.

Remitters from SCC DBS had less variance in activation patterns than the non-remitters.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 MH102238).

The authors thank St Jude Medical and Medtronic for donation of the DBS devices used in these experimental studies. This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01 MH102238).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: CCM is a paid consultant for Boston Scientific Neuromodulation and Kernel, as well as a shareholder in the following companies: Surgical Information Sciences; Autonomic Technologies; Cardionomic; Enspire DBS; Neuros Medical. HSM is a paid consultant with licensed intellectual property to St Jude Medical. REG has received grants from Medtronic Inc., Neuropace and MRI Interventions, honoraria from Medtronic Inc and MRI Interventions; and is a paid consultant to St Jude Medical Corp., Medtronic Inc., Neuropace, MRI Interventions, Neuralstem and SanBio. Authors, KSC, AMN, PRP, JKR, reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, et al. Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtzheimer PE, Mayberg HS. Deep Brain Stimulation for Psychiatric Disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:289–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranck JB., Jr Which elements are excited in electrical stimulation of mammalian central nervous system: A review. Brain Res. 1975;98(3):417–40. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehman JF, Greenberg BD, McIntyre CC, Rasmussen SA, Haber SN. Rules Ventral Prefrontal Cortical Axons Use to Reach Their Targets: Implications for Diffusion Tensor Imaging Tractography and Deep Brain Stimulation for Psychiatric Illness. J Neurosci. 2011;31(28):10392–402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0595-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vergani F, Martino J, Morris C, Attems J, Ashkan K, Dell’Acqua F. Anatomic Connections of the Subgenual Cingulate Region. Neurosurgery. 2016;79(3):465–72. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansen-Berg H, Gutman DA, Behrens TE, Matthews PM, Rushworth MF, Katz E, et al. Anatomical Connectivity of the Subgenual Cingulate Region Targeted with Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18(6):1374–83. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutman DA, Holtzheimer PE, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-berg H, Mayberg HS. A Tractography Analysis of Two Deep Brain Stimulation White Matter Targets for Depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(4):276–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsolaki E, Espinoza R, Pouratian N. Using probabilistic tractography to target the subcallosal cingulate cortex in patients with treatment resistant depression. Psychiatry Res. 2017;261:72–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lujan JL, Chaturvedi A, Choi KS, Holtzheimer PE, Gross RE, Mayberg HS, et al. Tractography-Activation Models Applied to Subcallosal Cingulate Deep Brain Stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2013;6(5):737–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riva-Posse P, Choi KS, Holtzheimer PE, McIntyre CC, Gross RE, Chaturvedi A, et al. Defining Critical White Matter Pathways Mediating Successful Subcallosal Cingulate Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76(12):963–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi KS, Riva-Posse P, Gross RE, Mayberg HS. Mapping the “Depression Switch” During Intraoperative Testing of Subcallosal Cingulate Deep Brain Stimulation. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(11):1252–60. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riva-Posse P, Choi KS, Holtzheimer PE, Crowell AL, Garlow SJ, Rajendra JK, et al. A connectomic approach for subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation surgery: prospective targeting in treatment-resistant depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2017 Apr 11; doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyagi Y, Shima F, Sasaki T. Brain shift: an error factor during implantation of deep brain stimulation electrodes. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(5):989–97. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/11/0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan MF, Mewes K, Gross RE, Škrinjar O. Assessment of Brain Shift Related to Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2008;86(1):44–53. doi: 10.1159/000108588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halpern CH, Danish SF, Baltuch GH, Jaggi JL. Brain Shift during Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery for Parkinson’s Disease. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2008;86(1):37–43. doi: 10.1159/000108587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obuchi T, Katayama Y, Kobayashi K, Oshima H, Fukaya C, Yamamoto T. Direction and Predictive Factors for the Shift of Brain Structure During Deep Brain Stimulation Electrode Implantation for Advanced Parkinson’s Disease. Neuromodulation. 2008;11(4):302–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2008.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elias WJ, Fu K-M, Frysinger RC. Cortical and subcortical brain shift during stereotactic procedures. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(5):983–8. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/11/0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sillay KA, Kumbier LM, Ross C, Brady M, Alexander A, Gupta A, et al. Perioperative Brain Shift and Deep Brain Stimulating Electrode Deformation Analysis: Implications for rigid and non-rigid devices. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41(2):293–304. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0650-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivan ME, Yarlagadda J, Saxena AP, Martin AJ, Starr PA, Sootsman WK, et al. Brain shift during bur hole-based procedures using interventional MRI. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(1):149–60. doi: 10.3171/2014.3.JNS121312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noecker AM, Choi KS, Riva-Posse P, Gross RE, Mayberg HS, McIntyre CC. StimVision Software: Examples and Applications in Subcallosal Cingulate Deep Brain Stimulation for Depression. Neuromodulation. 2017 Jun 27; doi: 10.1111/ner.12625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holtzheimer PE, Kelley ME, Gross RE, Filkowski MM, Garlow SJ, Barrocas A, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):150–8. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Moeller S, Auerbach EJ, Strupp J, Smith SM, Feinberg DA, et al. Evaluation of slice accelerations using multiband echo planar imaging at 3T. Neuroimage. 2013;83:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersson JLR, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2003;20(2):870–88. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S208–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Nunes RG, Clare S, et al. Characterization and propagation of uncertainty in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(5):1077–88. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersson JLR, Graham MS, Zsoldos E, Sotiropoulos SN. Incorporating outlier detection and replacement into a non-parametric framework for movement and distortion correction of diffusion MR images. Neuroimage. 2016;141:556–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, Benner T, Sorensen AG. Diffusion toolkit: a software package for diffusion imaging data processing and tractography. Proc Int Soc Mag Reson Med. 2007;15(3720) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox RW. AFNI: Software for Analysis and Visualization of Functional Magnetic Resonance Neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29(3):162–73. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaturvedi A, Lujan JL, McIntyre CC. Artificial neural network based characterization of the volume of tissue activated during deep brain stimulation. J Neural Eng. 2013;10(5):056023. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/5/056023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlaepfer TE, Bewernick BH, Kayser S, dler BMX, Coenen VA. Rapid Effects of Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Major Depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1204–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malone DA, Jr, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, Carpenter LL, Friehs GM, Eskandar EN, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(4):267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, Carpenter LL, Howland RH, Bhati MT, O’Reardon JP, et al. A Randomized Sham-Controlled Trial of Deep Brain Stimulation of the Ventral Capsule/Ventral Striatum for Chronic Treatment-Resistant Depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(4):240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rolston JD, Englot DJ, Starr PA, Larson PS. An unexpectedly high rate of revisions and removals in deep brain stimulation surgery: Analysis of multiple databases. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;33:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones DK, Knösche TR, Turner R. White matter integrity, fiber count, and other fallacies: The do’s and don’ts of diffusion MRI. Neuroimage. 2013;73:239–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlaepfer TE, Cohen MX, Frick C, Kosel M, Brodesser D, Axmacher N, et al. Deep Brain Stimulation to Reward Circuitry Alleviates Anhedonia in Refractory Major Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(2):368–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bewernick BH, Kayser S, Sturm V, Schlaepfer TE. Long-Term Effects of Nucleus Accumbens Deep Brain Stimulation in Treatment-Resistant Depression: Evidence for Sustained Efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(9):1975–85. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sartorius A, Kiening KL, Kirsch P, von Gall CC, Haberkorn U, Unterberg AW, et al. Remission of Major Depression Under Deep Brain Stimulation of the Lateral Habenula in a Therapy-Refractory Patient. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):e9–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viergever MA, Maintz JB, Klein S, Murphy K, Staring M, Pluim JP. A survey of medical image registration - under review. Med Image Anal. 2016;33:140–4. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2016.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143–56. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.