Abstract

Previous reports by us have determined that developmental exposure to the heavy metal lead (Pb) resulted in cognitive impairment in aging wildtype mice, and a latent induction in biomarkers associated with both the tau and amyloid pathways. However, the relationship between these two pathways and their correlation to cognitive performance needs to be scrutinized. Here, we investigated the impact of developmental Pb (0.2%) exposure on the amyloid and tau pathways in a transgenic mouse model lacking the tau gene. Cognitive function, and levels of intermediates in the amyloid and tau pathways following postnatal Pb exposure were assessed on young adult and mature transgenic mice. No significant difference in behavioral performance, amyloid precursor protein (APP), or amyloid beta (Aβ) levels was observed in transgenic mice exposed to Pb. Regulators of the tau pathway were impacted by the absence of tau, but no additional change was imparted by Pb exposure. These results revealed that developmental Pb exposure does not cause cognitive decline or change the expression of the amyloid pathway in the absence of tau. The essentiality of tau to mediate cognitive decline by environmental perturbations needs further investigation.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Aβ, APP, CDK5, p35/25, lead (Pb), tau protein, tau knock-out mouse model

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prominent form of dementia among aging individuals, predominantly in Western countries (Hebert et al., 2003). AD is characterized by cognitive decline and the accumulation of two kinds of protein aggregates; senile plaques composed of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), enriched with hyperphosphorylated tau. These pathologies cause synaptic loss in the brain, resulting in dementia (Selkoe, 1991; Tanzi and Bertram, 2008). Both NFTs and Aβ can exist independent of one another (Iqbal et al., 2010). Neurofibrillary degeneration in the absence of Aβ is seen in several tauopathies, such as: Guam Parkinsonism dementia complex, dementia pugilistica, corticobasal degeneration, Pick’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). These tauopathies are all present with neocortical lesions and are clinically characterized by dementia (Komori, 1999). Furthermore, neurofibrillary pathology, not β-amyloidosis, correlates best to the presence of dementia in humans (Arriagada et al., 1992).

AD is the most studied form of dementia; and aging is the biggest risk factor associated with late onset AD (LOAD). Familial, or early onset AD (EOAD), has been connected to mutations in one of the following genes; Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), Presenilin1 (PSEN1), or Presenilin 2 (PSEN2). Conversely, LOAD, which accounts for >95% of AD cases, has no clear genetic association, with the exception of carrying the Apolipoprotein E 4 (APOE4) allele (Bekris et al., 2010). While the etiology for the onset of LOAD remains obscure, the presence of specific susceptibility alleles has been debated (Gusareva et al., 2014; Rosenthal and Kamboh, 2014). The sporadic nature of LOAD suggests that any interference by environmental factors across the life span could impact the initiation and progression of the disease (Karch and Goate, 2015; Liddell et al., 2001; Rosenthal and Kamboh, 2014).

Among the various environmental toxicants, lead (Pb) presents a plausible environmental model for AD. While there are no epidemiological studies that have analyzed the relationship between Pb exposure and full blown AD, the effects of Pb exposure on cognitive decline have been established in several reports by the Normative Aging Study (NAS). The NAS reports that higher levels of Pb in blood and/or bone correlates to poor performance on a variety of cognitive tests (Payton et al., 1998; Weisskopf et al., 2007; Weisskopf et al., 2004; Wright et al., 2003). Past reports by our lab have similarly determined that early-life Pb exposure in mouse models results in worse performance in cognitive tests compared to age-matched controls. In addition to cognitive divergences, we found that these Pb exposed mice have latent overexpression of APP and Aβ, as well as elevated levels of tau, phospho-tau and tau regulators (Bihaqi et al., 2014b). Collectively, these findings establish that developmental Pb exposure results in cognitive decline and elevated levels of AD biomarkers in aging mice (Bihaqi et al., 2014a; Bihaqi et al., 2014b).

These past studies explored the effect of postnatal Pb exposure on wild type and transgenic mice, both of which had microtubule associated protein tau (MAPT) and APP genes (Bihaqi et al., 2014a; Bihaqi et al., 2014b; Dash et al., 2016). From those findings, it was not clear whether the exposure to Pb had simultaneous effects on the amyloid and tau pathways, or whether it selectively targeted one of these pathways in a way which impacted the other. Human biomarker studies have also revealed that Aβ levels buildup and plateau prior to tau levels and cognitive decline (Sperling et al., 2011). Therefore, the relationship between these two pathways and their connection to cognitive performance needs elucidation.

Tau-knockout mice permitted us to explore if amyloid pathologies and cognitive decline induced by Pb exposure are independent of or dependent on tau. Since we have extensively done lifespan studies on wild type mice developmentally exposed to Pb (Bihaqi et al., 2014b), we chose to add a third study group of unexposed wild type mice to this study to serve as a reference point for both behavioral and biochemical endpoints.

The goal of this study was to examine the status of the amyloid pathway and tau precursors following Pb exposure of mice that lack the tau gene. Amyloidogenic analysis investigated levels of APP and Aβ. Additional assays measured tau regulators CDK5 and p35/25. CDK5 is typically activated by p35 and then goes on to play a critical role in brain development. However, in tauopathies, p25, the truncated form of p35, hyper activates CDK5 leading to tau hyperphosphorylation and NFT (Kimura et al., 2014). In summary, we assessed cognitive performance, amyloidogenic effects, as well as intermediates in the tau pathway in tau-knockout mice developmentally exposed to Pb.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animal exposure

Human tau (hTau) transgenic knockout mice, which were the background for strain B6.Cg-Mapttm1(EGFP)Klt Tg(MAPT)8cPdav/J, were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. These transgenic mice were homozygous knockouts for the mouse MAPT gene (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). These mice were then bred in-house at University of Rhode Island to produce mice with no endogenous or human tau (h-tau) genes, known as the non-carrier (NC) mice. Postnatal day 1 (PND 1) was designated as 24 h after birth. All pups were pooled, and new litters were selected randomly and placed with each dam. The NC animals were divided into two groups. The control group, NC, consisted of 7 females and 2 males and were derived from dams which received regular tap water. Although the number of males and females in each group varied, the overall numbers used were similar with randomized male and female compositions. Past studies by us have shown no sex differences in the response to Pb exposure and these endpoints (Basha et al., 2005b; Wu et al., 2008). The NC/PbE group consisted of 4 males and 5 females, which were obtained from dams and were exposed to 0.2% Pb acetate from PND 1 to Postnatal day 20 (PND 20) through drinking water of the dam. During this period, several brain regions in the cerebrum important for memory and learning continue to develop and refine their connection. Blood levels have been shown to be 46.43 μg/dl during Pb exposure but are reduced to basal levels in adults (Basha et al., 2005b). The current CDC guidelines consider the safe level in humans to be 10 μg/dl. While this level is significantly higher than that seen in humans, it is important to note that rodents are much resistant to the deleterious effects of Pb. Recently we measured tissue Pb concentrations in brain samples from transgenic control and developmentally Pb exposed mice using quantitative ICP-MS. On PND20, a mean Pb concentration of 0.27ppm of wet weight was detected in unexposed mice, while an average of 1.95 ppm of wet weight was measured in Pb-exposed mice (Anwar et al., in press). Past reports by us showed that as the mice reached old age, the tissue Pb concentrations were identical to their age-matched controls (Basha et al., 2005b).

WT C57BL/6 mice were used as reference controls and were collected from dams that received only normal tap water. After the completion of the weaning period the dams were removed and the mice were shifted to separate cages. The mice were kept in the designated animal facility at the University of Rhode Island with a 12:12 h light-dark cycle (light on at 6:00 AM; light off at 6:00 pm). Food and water were provided ad libitum. This study defines young adult mice as 7 month, old and mature adult mice as 14-month old. Although the number of the animals used per group are unequal, but are statistically acceptable.

2.2. Behavioral tests

Behavior testing was conducted on mice groups as young adults and again later when matured. In order to evaluate the effect of developmental Pb exposure on the spatial learning and memory (a hippocampal formation-dependent task), animals were tested in the Morris water maze (MWM) (D’Hooge and De Deyn, 2001). The same mice were tested in the Morris water maze as young and as aged. The animals were randomized at the time of testing and were in good health during development or during the experiment. There were no notable effects on mortality.

The test was performed as described by Morris and coworkers (Morris et al., 1982). The maze apparatus consisted of a white pool (48″ diameter, 30″ height) filled with water to a depth of 14″. White, non-toxic paint (Crayola, New York City, NY, USA) was used to make the water opaque. The pool was virtually divided into four quadrants (NW, NE, SW, and SE). Distinct visual cues were placed along the sides of the pool to guide the animals to the escape platform. A clear Plexiglas escape platform (10cm2) was submerged in one of the quadrant, 0.5 cm below the surface of the water. This quadrant was known as the platform zone (PFZ) Temperature of the water was maintained at 25 + 2°C during all procedures.

A habituation trial allowed the mice to swim freely for 60 s to acclimate to the experiment, designated as Day 0. Mice received 3 daily training sessions for a total of 7 days with a 20-minute inter-trial interval. The starting position was randomly assigned between four possible positions while the platform remained fixed for all the trials. Each animal had a maximum duration of 60 s swimming to find the platform. For the first 3 days of the trial, a mouse that failed to locate the platform was gently guided towards platform by the experimenter and allowed to stay on the platform for 30 s. For the remaining 4 days of the trial, mice were taken out of the maze if they had not found the platform within 60 s. Following the completion of 7 days training session, probe trials were performed on 8th and 18th day in order to access the memory retention. For probe trials, the platform was removed and then the mice were allowed to swim for 60 s. A predilection for the platform location would be an indication that the mice had developed memory of the correct quadrant (the quadrant that contained the hidden platform during the previous training sessions). The swim paths and latencies were videotaped and analyzed with a computerized video-tracking system (ObjectScan, Clever Sys. Inc., Reston, VA, USA).

2.3. Sample preparation and Western blotting

Mature mice were euthanized by carbon-dioxide inhalation. Their brains were dissected and frontal cortex was stored at −80°C until analysis. Brain cortices were homogenized with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail, and 5μl phosphatase inhibitor per 1mL lysis buffer; Sigma-Aldrich). The homogenates were centrifuged at 1,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and supernatants were collected. Protein concentration was determined by Pierce bicinchoninic assay (BCA) kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For APP, CDK5 and p35/p25, 40 μg of total protein were separated onto 10% polyacrylamide gel at 120 V for 1.5 h and then transferred to polyvinylidienedifluoride (PVDF) membranes (GE-Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The membranes were then blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris Buffer Saline + 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1h at room temperature. Immunoblotting was performed after overnight exposure to the following antibodies diluted in TBST at 1:1000 with gentle agitation on a shaker at 4°C: APP/β-Amyloid (NAB228) Mouse mAb, CDK5 (D1F7M) Rabbit monoclonal antibody (mAb), and p35/p25 (C64B10) Rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Tech, Boston, MA, USA). On the following day, membranes were washed and exposed for 1h to IRDye 680LT Infrared Dye (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE, USA), goat anti-mouse/goat anti-rabbit diluted at 1:10,000 in TBST. For protein normalization membranes were incubated in β-Actin antibody diluted at 1:2000 in TBST for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed and exposed for 1 h to IRDye 680LT Infrared Dye (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE, USA), goat antimouse/goat antirabbit diluted at 1:10,000 in TBST. The images were developed using; an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE, USA).

2.4. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42)

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using human Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 assay IBL kits JP27713 and JP27711 determined Aβ levels (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Gunma, Japan). These kits are solid-phase sandwich ELISA with two kinds of highly specific antibodies, which are 100% reactive with mouse Aβ1–40 and 70% reactive with mouse Aβ1–42. The assay conditions were followed previously described methods (Bihaqi et al., 2014b; Wu et al., 2008). The levels of Aβ in the test samples were calculated relative to the standard curve generated for each plate.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Biochemical data are expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Assessment of performance in MWM daily training sessions between the NC, NC/PbE and the WT groups was determined using repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA), while probe trials differences between both groups were determined by unpaired two-tailed student T-test. The significance of differences between various treatments groups was determined by repeated measure ANOVA and Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison a posteriori analysis. All statistical analyses were conducted using Graph-Pad InStat 3 software (Graph-Pad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Probability P <0.05 was used as an upper threshold for significance.

3. Results

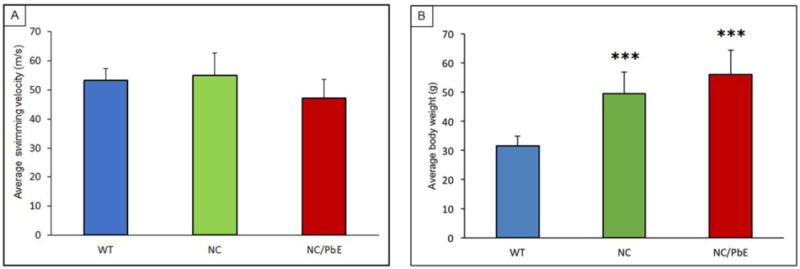

The Pb exposure model used in all past studies did not result in nutritional disturbances, or any overt changes in brain structure or anatomy in wildtype mice (Bihaqi et al., 2014b). However, in the absence of tau, we observed a significant (P<0.001) gain in weight in these mice when they matured (Figure 1A); though, we found no interference of such weight gain on animal mobility and motor functions, which were measured as average swimming velocities of NC and NC/PbE mice in comparison to WT (Figure 1B). These findings on weight and motor function are consistent with reports on tau-knockout mice (Lei et al., 2014; Morris et al., 2013).

Figure 1. Effect of tau silencing and developmental lead exposure on the swimming velocity and body weight in the mature mice.

(A) Body weight and (B) Mean swim velocity of mature mice during MWM probe trial 1 were measured. Each data point of the bar diagram is the mean ± SD, for each group (n= 9). ****P< 0.001 compared to WT.

3.1. Effect of developmental Pb exposure on performance in the MWM

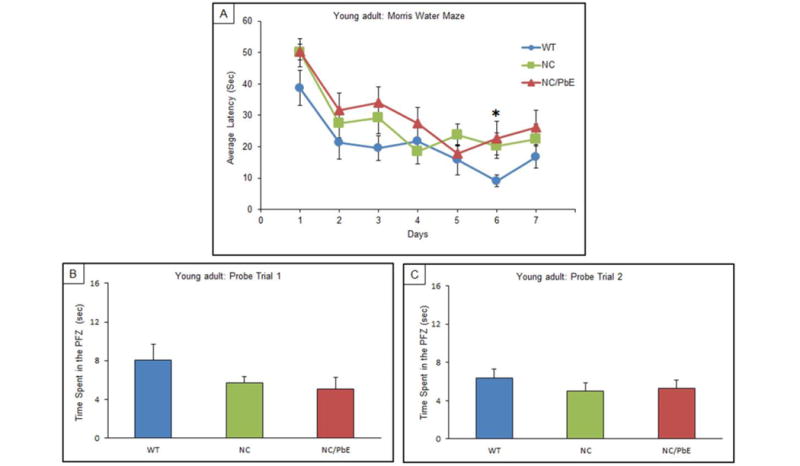

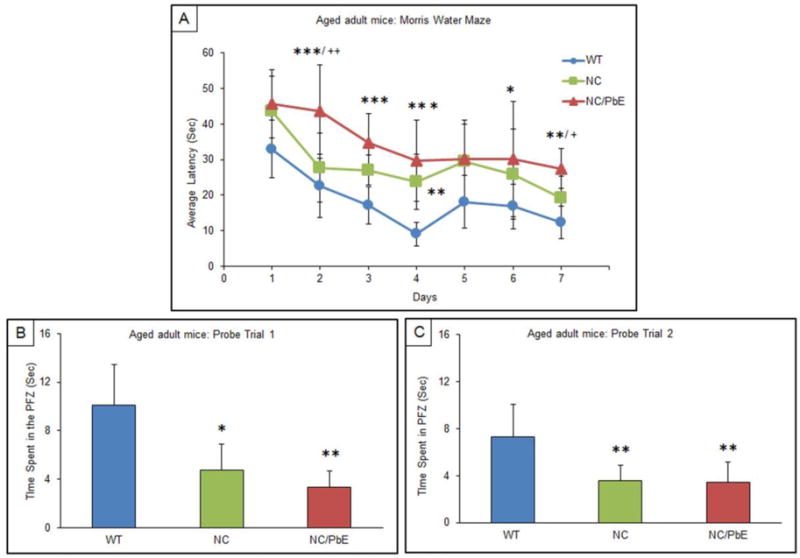

The behavioral test MWM was used to scrutinize difference in memory and spatial learning between the WT, NC, and NC/PbE groups of mice. Tau-knockout mice developmentally exposed to Pb were tested in MWM as young adults (7-months) and when they matured (14-months) along with respective controls. Learning was assessed by the reduction in latency to find the hidden platform during 7 days of training. No significant difference was observed between any of the three mice groups of young adult mice on all days except on day 6 (P <0.05) as compared to WT (Figure 2A). Probe trials (Probe 1 and Probe 2) undertaken in young adult mice indicated no significant difference in memory retention among the groups as well (Figure 2B and 2C). Although our results indicated that mature NC/PbE groups preformed significantly worse in the MWM compared to the reference control WT (P <0.001/day 2, 3 and 4; P <0.01/day 7, P <0.05/ day 6); significant difference was displayed by NC/PbE compared to the NC on day 2 (P <0.01) and day 7 (P <0.05) (Figure 3A). Moreover, no significance was displayed by NC compared to WT except on day 4 (P<0.01).

Figure 2. Acquisition and memory retention in young adult mice (7 months).

Training in the Morris water maze consisted of three trials per day for 7 days to locate a hidden platform. Memory retention was assessed by a 60 s probe trial 24 h after the last day of acquisition testing. (A) Mean escape latencies for finding the platform during daily training sessions. Memory retention was assessed by a 60 s probe trial 24 h; Probe trial 1(B), after the last day of acquisition testing, and again repeated for memory retention after 10 days; Probe trial 2 (C). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; for each group (n= 9). *P <0.05 compared with WT.

Figure 3. Acquisition and memory retention in mature mice (14 months).

Training in the Morris water maze consisted of three trials per day for 7 days to locate a hidden platform. Memory retention was assessed by a 60 s probe trial 24 h after the last day of acquisition testing. (A) Mean escape latencies for finding the platform during daily training sessions. Memory retention was assessed by a 60 s probe trial 24 h; Probe trial 1; (B), after the last day of acquisition testing, and again repeated for memory retention after 10 days; Probe trial 2 (C). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; for each group (n= 9). ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P <0.05 compared with WT, ++P< 0.01, +P< 0.05 compared with NC.

The NC/PbE deficit in memory was also confirmed by the probe trials. Probe trial 1, undertaken on the day following the completion of the MWM training session, revealed a significant decrease in the retention time (preference for PFZ) by NC (P <0.05) and NC/PbE (P<0.01) as compared to mature WT mice (Figure 3B). Significant (P <0.01) difference was also observed during probe trial 2 between NC and NC/PbE as compared to WT (Figure 3C). There was no statistical significant difference between the NC and NC/PbE group in probe trial 2.

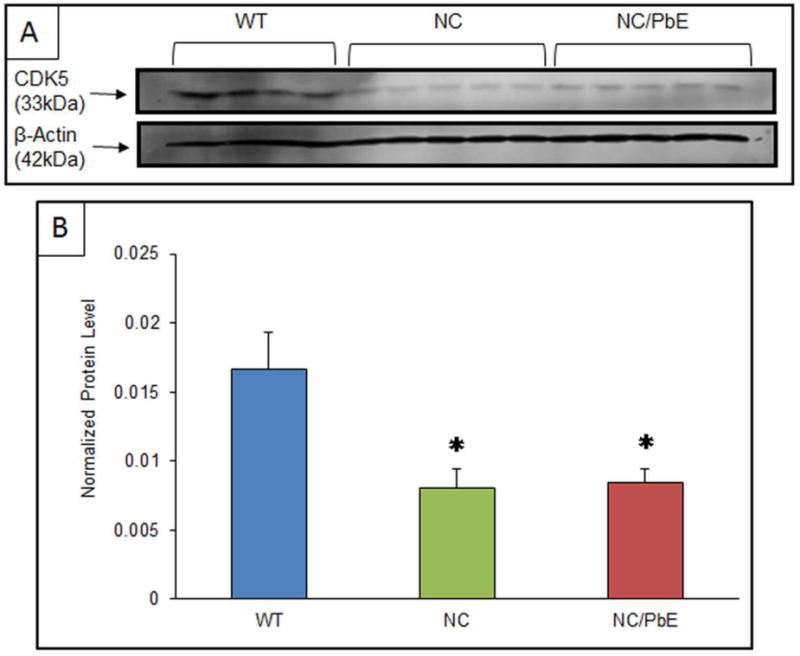

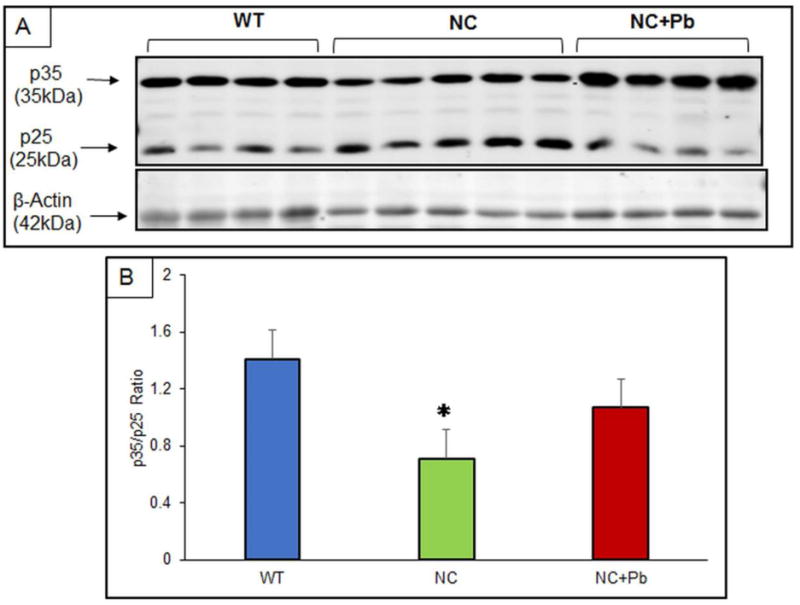

3.2. Latent protein expression of CDK5 and p35/p25

Antibodies directed against CDK5, and p35/p25 were used to determine the expression of the proteins in mature mice, which were exposed to Pb as pups. The protein expressions relative to β-Actin were profiled by western blotting. Normalized CDK5 levels in the NC and NC/PbE groups were found significantly (P <0.05) decreased as compared to the reference WT (Figure 4A and 4B). Normalized ratio of p35/p25 displayed a significant (P <0.05) change in NC/PbE compared to WT, whereas no significance was observed between NC and NC/PbE groups (Figure 5A and 5B).

Figure 4. CDK5 protein expression in mature mice.

(A) Changes in the CDK5 protein expression in the cerebral cortex of mature WT (n=4), NC (n=5) and NC/PbE (n=5) groups; (B) Quantification by normalization to β-Actin. Each data point in the bar diagram is the mean ± SEM; *P< 0.05 compared to WT.

Figure 5. Protein expression ratio of p35/p25 in mature mice.

(A) Changes in the p35/p25 protein expression in the cerebral cortex of mature WT (n=4), NC (n=5) and NC/PbE (n=4) groups; (B) p35/p25 ratio. Each data point in the bar diagram is the mean ± SEM; *P< 0.05 compared to WT.

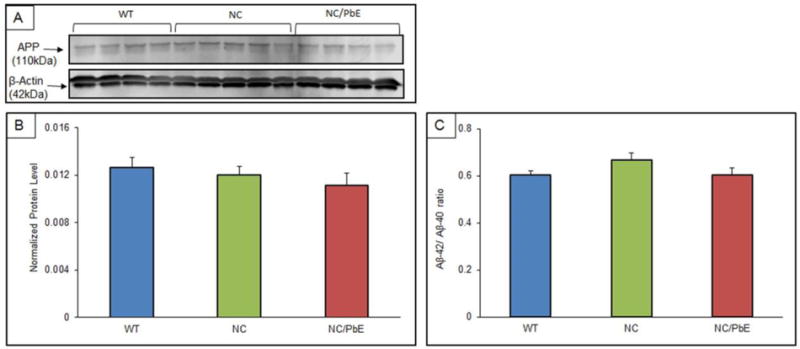

3.3. Effect of aging and developmental exposure of Pb on APP and Aβ levels

Western blot analysis showed no significant difference between the three mice groups in terms of normalized APP levels (Figure 6A and 6B). Similarly, changes in Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 levels examined by ELISA revealed no significance in the Aβ levels between the three mice groups (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Protein expression of APP protein expression and Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio in mature mice.

(A) Changes in the APP protein expression in the cerebral cortex of mature WT (n=4), NC (n=5), and NC/PbE (n=4), groups; (B) Quantification by normalization to β-Actin; (C) Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio. Each data point in the bar diagram is the mean ± SEM. No significance was observed between the groups.

4. Discussion

The “chicken and egg” cliché or the “trigger and bullet” phrase has plagued the AD field for decades. Does Aβ trigger the conversion of tau from a normal to a toxic state, or does tau enhances Aβ toxicity? Which comes first and what is the causal link between these two hallmarks features of AD continue to beg for more answers. An accumulating body of evidence has indicated that soluble forms of Aβ and tau work together, independently of their accumulation into plaques and tangles, to drive healthy neurons into the diseased state and that toxic properties of Aβ require tau (Bloom, 2014). Evidence that tau is required for Aβ toxicity in-vivo, emerged from crossing tau knockout mice with hAPPJ20 mice that overexpress human APP. Remarkably, loss of tau genes protected hybrids against the learning and memory deficits and confers protection against harmful effects of Aβ accumulation(Roberson et al., 2007). In contrast, other reports show that Aβ clearly functions upstream of tau (Gotz et al., 2001; Hurtado et al., 2010).

Past reports from our lab have demonstrated that WT mice and primates exposed to Pb in early life have latent cognitive decline, enhanced tau and Aβ levels, and exaggerated amyloid and tau pathology (Bihaqi et al., 2014a; Bihaqi et al., 2014b; Bihaqi and Zawia, 2013). These past exposure studies occurred in animal models that had both the APP and tau genes. Here we wanted to explore the impact of the absence of the tau gene on behavioral performance and biomarker levels of mice exposed to Pb as pups. The performance of the NC/PbE mice was compared to the unexposed NC controls. Wild type mice were not included in the lifespan exposure protocol but were added as reference controls.

Behavioral analysis depicted that, while mature control tau-knockout mice (NC) and those exposed to Pb as pups (NC/PbE) performed poorly compared to the WT unexposed reference group, there were no differences in cognitive performance between the NC and NC/PbE groups when compared to each other. Therefore, developmental exposure to Pb did not affect the behavioral performance of these animals in the absence of the tau gene. This was in sharp contrast to our previously published studies, which showed that WT mice exposed in early life to Pb perform progressively worse after 15-months of age than their unexposed counterparts(Bihaqi et al., 2014b). In summary, the absence of tau compromises an animal’s cognitive ability and the presence of tau is essential for the cognitive impact of Pb exposure.

Previous reports by us examined the effects of early-life Pb exposure on amyloid and tau biomarkers in animals that possess both genes. We discovered that postnatal Pb exposure of WT led to an overexpression of AD related biomarkers in aged mice (Bihaqi et al., 2014a; Bihaqi et al., 2014b). The present study investigated the amyloid and tau pathways following postnatal Pb exposure in mice lacking the tau gene. CDK5, a kinase involved in tau phosphorylation, exhibited significantly lower levels of expression in NC and NC/PbE compared to WT mice. The ratio of p35/p25 was also significantly reduced compared to WT. As with the behavioral testing, there was no difference between the NC and NC/PbE exposed groups. Again, we found that postnatal Pb exposure did not alter tau-related biomarker levels in the absence of the tau. This further reinforced the essentiality of the tau gene to mediate the influence of past Pb exposure on behavioral and biochemical pathways related to tauopathy.

While intermediates in the tau pathway were altered in response to the absence of tau but, where not exacerbated by prior exposure to Pb; APP and Aβ levels were virtually identical for all three experimental groups. This suggested that tau is necessary for Pb exposure to affect APP and Aβ. This further reinforced the essentiality of the tau gene to mediate the influence of prior Pb exposure on behavioral and biochemical pathways related to tauopathy and amyloidogenesis.

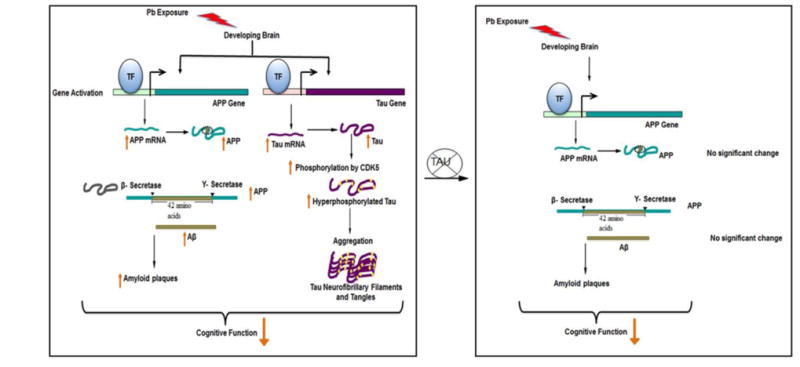

Leroy and Coworkers found that in mice with an APP/PSEN1 mutation, eliminating tau reduced memory deficits, synaptic loss, and Aβ plaques, thus reducing amyloidogenic processing of APP normally found in the mutated mice (Leroy et al., 2012). Other studies have suggested that levels of phospho-tau or total tau levels do not directly influence Aβ, but that tau plays a key role in mechanisms of Aβ-induced neurodegeneration (Guo et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2015; Roberson et al., 2007). A differing view proposes the idea that overexpression of APP in cells promotes the formation of intracellular tau aggregation (Guo et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2015; Pooler et al., 2015; Takahashi et al., 2015). Clearly tau and Aβ are involved in some loop and their actions impact each other. Our current study suggests that tau is required for Pb to alter both amyloid and tau-related biomarkers. Tau is also required at least partially for Pb to have effects on cognitive function as well as AD biomarkers. Future studies by our lab will explore the implications of these inter-connections vis-à-vis environmental exposure and disease risk.

Figure 7. Proposed Scheme of Events.

This summary is proposed based on multiple published studies and the results of experiments presented in this paper. (Left) Developmental exposure to Pb induces latent APP and Tau gene expression and subsequent intermediates associated with these pathways resulting in an enhancement in amyloid and tau pathology and ensuing cognitive decline. (Right) In the absence of the tau gene, intermediates involved in the amyloid pathway displayed no significant change in tau knockout mice developmentally exposed to Pb; however, cognitive decline occurred. This suggests that tau is a necessary player for Pb exposure to influence the amyloid pathway, but the impact on cognitive decline may be associated with yet another to be determined player in the neurodegeneration scheme (Basha et al., 2005a; Bihaqi et al., 2014a; Bihaqi and Zawia, 2013)

High Lights.

Cognitive function was impaired by Pb exposure in the absence of tau.

The amyloid pathway was not altered by Pb exposure in the absence of tau.

Tau is required for Pb exposure to alter both amyloid and Tau related biomarkers.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42:631–639. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basha MR, Murali M, Siddiqi HK, Ghosal K, Siddiqi OK, Lashuel HA, Ge YW, Lahiri DK, Zawia NH. Lead (Pb) exposure and its effect on APP proteolysis and Abeta aggregation. FASEB J. 2005a;19:2083–2084. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4375fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basha MR, Wei W, Bakheet SA, Benitez N, Siddiqi HK, Ge YW, Lahiri DK, Zawia NH. The fetal basis of amyloidogenesis: exposure to lead and latent overexpression of amyloid precursor protein and beta-amyloid in the aging brain. J Neurosci. 2005b;25:823–829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4335-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekris LM, Yu CE, Bird TD, Tsuang DW. Genetics of Alzheimer disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2010;23:213–227. doi: 10.1177/0891988710383571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihaqi SW, Bahmani A, Adem A, Zawia NH. Infantile postnatal exposure to lead (Pb) enhances tau expression in the cerebral cortex of aged mice: relevance to AD. Neurotoxicology. 2014a;44:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihaqi SW, Bahmani A, Subaiea GM, Zawia NH. Infantile exposure to lead and late-age cognitive decline: relevance to AD. Alzheimers Dement. 2014b;10:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihaqi SW, Zawia NH. Enhanced taupathy and AD-like pathology in aged primate brains decades after infantile exposure to lead (Pb) Neurotoxicology. 2013;39:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom GS. Amyloid-beta and tau: the trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:505–508. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hooge R, De Deyn PP. Applications of the Morris water maze in the study of learning and memory. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;36:60–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash M, Eid A, Subaiea G, Chang J, Deeb R, Masoud A, Renehan WE, Adem A, Zawia NH. Developmental exposure to lead (Pb) alters the expression of the human tau gene and its products in a transgenic animal model. Neurotoxicology. 2016;55:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293:1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1062097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Li H, Cole AL, Hur JY, Li Y, Zheng H. Modeling Alzheimer’s disease in mouse without mutant protein overexpression: cooperative and independent effects of Abeta and tau. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusareva ES, Carrasquillo MM, Bellenguez C, Cuyvers E, Colon S, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC, Dickson DW, Mahachie John JM, Bessonov K, Van Broeckhoven C, Consortium, G. Harold D, Williams J, Amouyel P, Sleegers K, Ertekin-Taner N, Lambert JC, Van Steen K, Ramirez A. Genome-wide association interaction analysis for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:2436–2443. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado DE, Molina-Porcel L, Iba M, Aboagye AK, Paul SM, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. A{beta} accelerates the spatiotemporal progression of tau pathology and augments tau amyloidosis in an Alzheimer mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1977–1988. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX, Grundke-Iqbal I. Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:656–664. doi: 10.2174/156720510793611592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch CM, Goate AM. Alzheimer’s disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Ishiguro K, Hisanaga S. Physiological and pathological phosphorylation of tau by Cdk5. Front Mol Neurosci. 2014;7:65. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T. Tau-positive glial inclusions in progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration and Pick’s disease. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:663–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei P, Ayton S, Moon S, Zhang Q, Volitakis I, Finkelstein DI, Bush AI. Motor and cognitive deficits in aged tau knockout mice in two background strains. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy K, Ando K, Laporte V, Dedecker R, Suain V, Authelet M, Heraud C, Pierrot N, Yilmaz Z, Octave JN, Brion JP. Lack of tau proteins rescues neuronal cell death and decreases amyloidogenic processing of APP in APP/PS1 mice. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1928–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell MB, Lovestone S, Owen MJ. Genetic risk of Alzheimer’s disease: advising relatives. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:7–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore S, Evans LD, Andersson T, Portelius E, Smith J, Dias TB, Saurat N, McGlade A, Kirwan P, Blennow K, Hardy J, Zetterberg H, Livesey FJ. APP metabolism regulates tau proteostasis in human cerebral cortex neurons. Cell Rep. 2015;11:689–696. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Hamto P, Adame A, Devidze N, Masliah E, Mucke L. Age-appropriate cognition and subtle dopamine-independent motor deficits in aged tau knockout mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1523–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RG, Garrud P, Rawlins JN, O’Keefe J. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature. 1982;297:681–683. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payton M, Riggs KM, Spiro A, Weiss ST, 3rd, Hu H. Relations of bone and blood lead to cognitive function: the VA Normative Aging Study. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1998;20:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(97)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pooler AM, Polydoro M, Maury EA, Nicholls SB, Reddy SM, Wegmann S, William C, Saqran L, Cagsal-Getkin O, Pitstick R, Beier DR, Carlson GA, Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT. Amyloid accelerates tau propagation and toxicity in a model of early Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:14. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, Gerstein H, Yu GQ, Mucke L. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal SL, Kamboh MI. Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Genes and the Potentially Implicated Pathways. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2014;2:85–101. doi: 10.1007/s40142-014-0034-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Amyloid protein and Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Am. 1991;265:68–71. 74–66, 78. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1191-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Miyata H, Kametani F, Nonaka T, Akiyama H, Hisanaga S, Hasegawa M. Extracellular association of APP and tau fibrils induces intracellular aggregate formation of tau. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:895–907. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1415-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi RE, Bertram L. Alzheimer’s disease: The latest suspect. Nature. 2008;454:706–708. doi: 10.1038/454706a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Proctor SP, Wright RO, Schwartz J, Spiro A, Sparrow D, 3rd, Nie H, Hu H. Cumulative lead exposure and cognitive performance among elderly men. Epidemiology. 2007;18:59–66. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000248237.35363.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Wright RO, Schwartz J, Spiro A, Sparrow D, 3rd, Aro A, Hu H. Cumulative lead exposure and prospective change in cognition among elderly men: the VA Normative Aging Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:1184–1193. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RO, Tsaih SW, Schwartz J, Spiro A, 3rd, McDonald K, Weiss ST, Hu H. Lead exposure biomarkers and mini-mental status exam scores in older men. Epidemiology. 2003;14:713–718. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000081988.85964.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Basha MR, Brock B, Cox DP, Cardozo-Pelaez F, McPherson CA, Harry J, Rice DC, Maloney B, Chen D, Lahiri DK, Zawia NH. Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-like pathology in aged monkeys after infantile exposure to environmental metal lead (Pb): evidence for a developmental origin and environmental link for AD. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4405-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]