Abstract

Introduction

Subtle changes in IADLs often accompany the onset of MCI but are difficult to measure using conventional tests.

Method

Weekly online survey metadata metrics, annual neuropsychological tests, and an IADL questionnaire were examined in 110 healthy older adults with intact cognition (M age = 85 years) followed for up to 3.6 years; 29 transitioned to MCI during study follow-up.

Results

In the baseline period, incident MCI participants completed their weekly surveys 1.4 hours later in the day than stable cognitively intact, p = .03, d = 0.47. Significant associations were found between earlier survey start time of day and higher memory (r = −0.34; p < .001) and visuospatial test scores (r = −0.37; p < .0001). Longitudinally, incident MCI participants showed an increase in survey completion time by three seconds per month over the year prior to diagnosis compared to stable cognitively intact (β= 0.12, SE =0.04, t = 2.8; p = .006).

Discussion

Weekly online survey metadata allowed for detection of changes in everyday cognition before transition to MCI.

Keywords: everyday cognition, activity monitoring, longitudinal, aging, computer use, preclinical AD, older adults, in-home technology, ecological validity

1. Introduction

Early detection of cognitive and functional decline in MCI and prodromal AD is critical for effective optimal clinical management as well as large scale screening and implementation of disease modifying treatments as they become available. Jedynak et al1 examined the timing and course of biomarker changes with data from 687 participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study. A neuropsychological word list memory task was found to be the earliest marker to become abnormal, followed by hippocampal volume and concentration of amyloid beta. In another ADNI study, Edmonds et al2 found that amyloid accumulation and subtle cognitive decline were equally common first signals of change in healthy older adults who later transitioned to MCI. Tarnanas et al3 showed that two computerized simulated complex activities of daily living (IADL) tasks accounted for a significant amount of the variance in early progression from normal to MCI, above and beyond other common biomarkers. Verlinden et al4 found that individuals who later developed AD started declining on an IADL measure 5–6 years before dementia diagnosis. Taken together, these studies suggest that subtle cognitive and IADL changes may be among the earliest signals of meaningful change in those who later develop MCI and AD. Given the high cost, invasive nature, unclear clinical utility of in-vivo biomarker imaging, and weak association between biomarkers and clinical outcomes5, there is a continued need to identify sensitive cognitive and IADL markers that are clinically relevant, cost effective, and scalable to reach the growing population of older adults.

Measurement of subtle, insidious decline in complex higher order daily function (e.g., everyday cognition), a hallmark of neurodegenerative disease, is hindered by the current episodic and clinic based assessment paradigm. Infrequent administration of functional tests does not allow for tracking of subtle within-person variability over time, which has been shown to be a powerful and sensitive predictor of incident cognitive decline.6, 7 Although older adults with MCI demonstrate slower, less efficient, and less accurate completion of daily activities than their cognitively intact counterparts,8–10 these aspects of daily performance are not typically captured by conventional IADL tests and questionnaires.

Advances in wireless technology, pervasive computing, and high dimensional data analytics have made it possible to unobtrusively and continuously monitor cognitively demanding routine activities in one’s own environment through commonly used devices.11–17 Computer use is a highly complex functional activity that is becoming increasingly common among older adults, with 59% of individuals’ age 65 or older reporting daily online use and 47% having a high-speed broadband connection.18 With the goal of assessing everyday cognition directly within the IADL domain of home computer use, we took advantage of a weekly self-administered online health survey that is deployed in our longitudinal aging studies. Specifically, we derived online survey “metadata” metrics based on survey engagement patterns of MCI and cognitively intact participants, with the idea that subtle cognitive difficulties seen in early MCI (e.g., slower, less efficient, less consistent performance on tasks) would be automatically captured and reflected in participants’ self-administration, engagement with, and conduct of the online survey over time. In an initial study we showed that weekly online survey metadata could be used to discriminate between MCI and cognitively intact groups 10.

In the present study we extend these findings by first examining baseline period cross-sectional group differences between healthy older adults who later transitioned to MCI (incident MCI group) and healthy older adults who remained cognitively intact (stable cognitively intact group) using the first three months of available online survey metadata on survey completion time (in minutes), survey completion time of day, and survey adherence. Based on results from our previous study, we were interested to see if there would be identifiable differences in the survey metadata metrics between the two groups.

Our second aim was to examine cross-sectional associations between the online survey metadata (using the first 3 months of data), conventional neuropsychological tests, and a functional (IADL) questionnaire. Based on available research19, we expected that our survey metadata metrics would be significantly associated with neuropsychological and functional test scores. Our third aim was to examine whether there were within-person changes in the online survey metadata in incident MCI individuals in the 12-month period prior to diagnosis of MCI based on annual neuropsychological test scores. We hypothesized that incident MCI older adults would manifest subtle changes in online survey engagement in the 12-month period leading up to MCI diagnosis compared to stable cognitively intact older adults’ last 12-month period of available data.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

All participants provided written informed consent and were already enrolled in ongoing longitudinal studies of in-home monitoring (www.orcatech.org). Participants were recruited from the Portland, Oregon, metropolitan area through presentations at local retirement communities. The study protocols were approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (Life Laboratory IRB #2765; ISSAC IRB #2353). Additional details of the sensor systems and study protocols have been published elsewhere.11, 17 Inclusion criteria for the present study were: 60 years and older, living independently (living with a companion or spouse was allowed, but not as caregiver), cognitively intact at baseline as evidenced by not meeting criteria for MCI based on Jak’s comprehensive MCI criteria20 and with the criteria outlined by the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroup21, and in average health for age without poorly controlled medical illnesses as confirmed by a score of < 4 in every category on the modified Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS).22 For the present study, we report data for 110 participants who were cognitively intact at baseline and had available online survey data in the selected time frame (2011–2015). In 2011, all participants included were non-depressed (GDS 15-item23 =<5) and cognitively intact (M age = 84.8 years; 77% female). Of these individuals, 29 (26%) transitioned to MCI (M age = 86.0; 79% female) at an annual clinical follow-up visit. On average the incident MCI group had 36.1(SD = 23.1) months of follow up (range = 0.8 – 76.2) and the stable cognitively intact group had 80.7 (SD = 33.4) months of follow up (range = 11.1 – 109.1).

Clinical Assessment Procedures

Participants received clinical and neuropsychological assessments during annual visits in their homes using a standardized battery of tests as part of the National Institute on Aging, National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Alzheimer’s Disease Centers protocol including: Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15), and Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ).24 Classification of incident MCI during the study period was consistent with the comprehensive criteria defined by Jak and colleagues20, 25 and with the criteria outlined by the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroup (Table 1).21 Classification of incident MCI or stable cognitively intact was made at each participant’s subsequent annual clinical evaluation.

Table 1.

Criteria for classification of incident MCI during the study period

|

To examine associations between neuropsychological test scores and online survey metadata in the entire sample in cross-sectional analyses, global and domain specific cognitive z-scores were tabulated from 2–3 representative neuropsychological tests for each of five cognitive domains (working memory, attention/processing speed, memory, executive function, and visual perception/construction). Although each test requires multiple cognitive skills, we classified the tests assessing related abilities into standard representative cognitive domains. Most tests were used in the algorithms to compute cognitive domain z-scores for MCI classification and for correlation analyses but were categorized into domains slightly differently based on test availability at time of analysis. Cognitive domain z-scores were calculated using group mean and standard deviations of the raw test scores from all cognitively intact subjects at study entry into the ORCATECH cohorts. The individual participant scores were z-normalized, summed, and averaged.

2.2 Weekly Online Survey Metadata Metrics

On the same day and time each week, participants were sent the online survey via email (Figure 1). Participants used personal computers with high speed internet access in their homes. The survey is structured in a forced-choice (yes/no) format and is composed of 13 items about mood, pain level, loneliness, as well as life events. If participants responded ‘yes’ to an item, follow-up questions were presented requiring additional details via text entry. In addition, event start and end dates were required and were chosen from a drop-down calendar for any life event that was endorsed (e.g., hospitalization, vacation). The time that the survey was started and submitted was automatically time stamped and recorded. Online survey metadata metrics were computed based on survey engagement patterns based on factors related to participants’ self-administration, engagement with, and conduct of the online survey. Commercially available software and established algorithms were used to derive and analyze the survey metadata measures of interest: Time to Complete (in minutes), Time of Day Completed (in clock time of day), and Adherence (%; defined as number of surveys completed / number of weeks in analysis window * 100).

Figure 1.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Cross sectional group comparisons of demographic and clinical variables were made using Students t-test or Wilcoxon ranked sum test for continuous variables and the Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables at participants’ 2011–2012 annual evaluation. To examine the online survey metadata metrics cross-sectionally, we used the first three months of available online survey data closest to the 2011–2012 annual clinical evaluation for each participant (Table 2). Cohen’s d was computed as a measure of effect size for group comparisons. Spearman nonparametric correlations were used to examine associations between neuropsychological test scores (global and domain-specific cognitive z-scores) and online survey metadata cross-sectionally in the total sample, adjusting for multiple comparisons (Table 3).

Table 2.

Demographics, Baseline Cognitive Domain z-scores and Baseline Period Survey Metadata Metrics. Mean and standard deviation or percentages are presented.

| Variable | Total | Incident MCI | Stable cognitively intact | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N | 110 | 29 | 81 | |

| Age at baseline (yrs) | 84.8 (6.8) | 86.0 (6.1) | 84.4 (7.0) | 0.21 |

| Sex (% female) | 77% | 79% | 77% | 0.76 |

| Education (yrs) | 15.5 (2.5) | 15.3 (2.4) | 15.5 (2.6) | 0.73 |

| WRAT Reading Level | 74.4 (13.4) | 70.6 (17.8) | 75.8 (11.2) | 0.29 |

| MMSE | 28.8 (1.2) | 28.4 (1.4) | 29.0 (1.2) | 0.053 |

| Global Cognition z-score | 0.17 (0.52) | −0.15 (0.47) | 0.28 (0.49) | <0.0001 |

| Executive function z-score | 0.20 (0.68) | −0.17 (0.48) | 0.33 (0.69) | <0.0001 |

| Working memory z-score | 0.00 (0.88) | −0.04 (0.96) | 0.01 (0.86) | 0.76 |

| Attention z-score | 0.10 (0.62) | −0.17 (0.61) | 0.20 (0.60) | <0.01 |

| Memory z-score | 0.17 (0.81) | −0.33 (0.74) | 0.36 (0.77) | <0.0001 |

| Visuospatial z-score | 0.42 (0.69) | 0.10 (0.67) | 0.54 (0.66) | <0.01 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15) | 0.6 (0.9) | 1.0 (1.3) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.23 |

| Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.96 |

| Mean duration of follow-up, months | 68.9 (36.7) | 36.1 (23.1) | 80.7 (33.4) | <0.0001 |

| Baseline period adherence (surveys completed/weeks *100%) | 75 (27) | 68 (31) | 78 (25) | 0.09 |

| Baseline period mean time to complete survey (minutes) | 3.2 (2.0) | 3.1 (2.0) | 3.3 (2.0) | 0.55 |

| Baseline period mean survey start time of day | 1:18 PM (3.0 hrs) | 2:18 PM (3.1 hrs) | 12:54 PM (2.9 hrs) | 0.03 |

Table 3.

Spearman’s r correlations between baseline period cross-sectional survey metadata and global and domain-specific cognitive z-scores and Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ); n=110

| Global | Executive function | Attention | Memory | Working Memory | Visuospatial | FAQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Variable | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Survey Adherence (%) | r=0.24 | r=0.22 | r=0.13 | r=0.25 | r=−0.01 | r=0.20 | r=−0.05 |

| p=0.01 | p=0.02 | p=0.18 | p<0.01 | p=0.90 | p=0.03 | p=0.64 | |

|

| |||||||

| Mean survey completion time | r=−0.15 | r=−0.20 | r=−0.23 | r=−0.08 | r=0.10 | r=−0.03 | r=0.02 |

| p=0.14 | p=0.04 | p=0.02* | p=0.43 | p=0.30 | p=0.77 | p=0.83 | |

|

| |||||||

| Mean survey start time of day | r=−0.26 | r=−0.14 | r=−0.02 | r=−0.34 | r=−0.03 | r=−0.37 | r=0.19 |

| p<0.01 | p=0.14 | p=0.83 | p<0.001* | p=0.74 | p=0.0001* | p=0.07 | |

p <.0024 = significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons

Lastly, we used linear mixed effects models for repeated measures over time (SAS Proc Mixed) to analyze the impact of group (incident MCI vs. stable cognitively intact) on each of the survey metadata metrics with fixed effects of follow-up time, group, and the interaction between follow-up time and group adjusted for age, education, and multiple comparisons using each participants’ last available one year period (Table 4). This procedure prevented listwise deletion due to missing data. For participants who transitioned to MCI during the study period, only survey data collected in the 12-month period prior to MCI classification were used in longitudinal analyses. For cognitively stable participants, only survey data collected in the last 12-month period available were used in longitudinal analyses. Using each participant’s last year of data only for longitudinal analyses controlled for group differences in overall follow-up duration. Survey metadata metrics after MCI incidence were not included in the models. Online survey completion time models were adjusted for number of items endorsed. The time scale for linear mixed effects models 1 and 2 was measured in weeks because the survey is administered on a weekly basis. For model 3 we calculated adherence per quarter (three-month period). We grouped the year into four three-month windows and determined how many surveys each participant submitted during each quarter. Analyses were performed using SAS software 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Table 4.

Models of longitudinal survey metadata by group over one year follow-up (Stable cognitively intact vs. Incident MCI)

| Model 1 Survey Completion Timea |

Model 2 Survey Start Time of Dayb |

Model 3 Survey Adherencec |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Coefficient | p-value | Coefficient | p-value | Coefficient | p-value |

| Incident MCI vs. Stable cognitively intact | −16.90 | 0.52 | 159.1 | 0.01* | −2.86 | 0.04 |

| Follow-Up Time | −0.00 | 0.96 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.15 |

| Incident MCI * Follow-Up Time | 0.12 | 0.006* | −0.16 | 0.09 | 0.64 | 0.11 |

| Age (yrs) | 2.92 | 0.004* | 3.25 | 0.20 | −0.14 | 0.011* |

| Education (yrs) | −0.08 | 0.98 | 4.57 | 0.51 | 0.04 | 0.81 |

Measured in seconds; adjusted for items endorsed (#)

Measured in clock time (minutes from 5am)

Number of surveys completed without assistance per three month interval

For the incident MCI group, subset to only the time period prior to transition to MCI.

p < 0.017 is significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons

3. Results

Baseline demographic, clinical, cognitive domain composite z-scores, and online survey metadata characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2. On average the incident MCI group had 36.1(SD = 23.1) months of follow up (range= 0.8 – 76.2) and the stable cognitively intact group had 80.7 (SD = 33.4) months of follow up (range= 11.1 – 109.1), p < .0001. At baseline, there were no significant differences between stable cognitively intact and incident MCI groups in age, sex, education, Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) reading scores (a measure of premorbid IQ), self-reported mood (GDS-15), global cognition via a screening measure (MMSE), or informant-rated IADL (functional) level in complex activities (FAQ). There were significant group differences in the neuropsychological battery composite domain z-scores of global cognition (Incident MCI M = −0.15, SD = 0.47; Stable cognitively intact M = 0.28, SD = 0.49, p <.0001, d = 0.83), executive functioning (Incident MCI M = −0.17, SD= 0.48; Stable cognitively intact M = 0.33, SD = 0.69, p <.0001, d = 0.74), memory (Incident MCI M = −0.33, SD = 0.74; Stable cognitively intact M = 0.36, SD = 0.77, p <.0001, d = 0.85), attention (Incident MCI M = −0.17, SD = 0.61; Stable cognitively intact M = 0.20, SD = 0.60, p < .01, d = 0.60, and visual-spatial abilities (Incident MCI M = 0.10, SD = 0.67; Stable cognitively intact M = 0.54, SD = 0.66, p < .01, d = 0.64).

3.1 Cross-sectional differences in survey metadata between stable cognitively intact and incident MCI groups

During the cross-sectional baseline period (first three months of available survey data) incident MCI individuals completed their online surveys on average 1.4 hours later in the day (2:18 PM) compared to stable cognitively intact individuals (12:54 PM), p = 0.03, d = 0.47. There were no significant group differences in variability (SD) around the survey metric means for each group during the 3-month baseline period. During the baseline period, the average online survey completion time was 3.1 minutes (± 2.0 minutes) for incident MCI and 3.3 (± 2.0 minutes) for stable cognitively intact groups, respectively, p = .55 (Table 2). Survey adherence during the baseline period was 68% for the incident MCI participants and 78% for the stable cognitively intact participants, p = .09.

3.2 Cross-sectional associations between survey metadata, neuropsychological, and functional test scores

There were significant associations between baseline neuropsychological test performance in the entire sample with survey metadata during the cross-sectional baseline period, p’s < .05 (Table 3). After controlling for multiple comparisons, poorer memory and visual-spatial abilities remained significantly correlated with later online survey start time of day, (r’s = −.34 and −.37) p’s < .001 (Table 3). There were no significant associations between the online survey metadata metrics and FAQ total scores.

3.3 Longitudinal analysis of online survey metadata and transition to MCI in the 12-month period prior to diagnosis

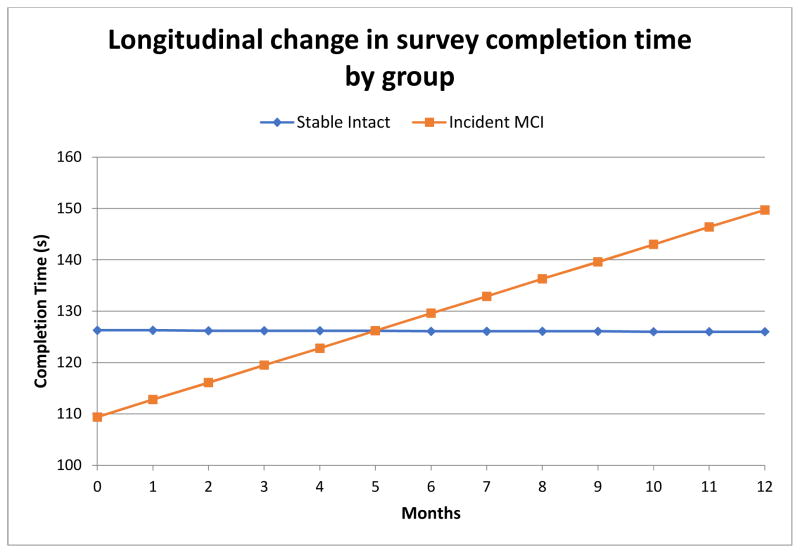

The linear mixed effects model for survey completion time (in seconds) revealed no significant main effects of group or time, although the group-time interaction was statistically significant (β= 0.12, SE = 0.04, t = 2.8; p = .006); incident MCI individuals showed an increase (about half a minute more per year or a 17% total increase) in their completion time over the one year period (slope) compared to stable cognitively intact participants (Table 4, Figure 2). The linear mixed effects model for start time of day revealed a main effect of time for all participants; over the one-year period participants started their survey at increasingly later times in the day (slope) (β = 0.08, SE = 0.04, t = 2.1; p = .04). This effect was not significant after controlling for multiple comparisons. There was also a main effect of group; incident MCI participants started their survey later in the day than stable cognitively intact participants (β = 159.1, SE = 62.5, t = 2.6; p = .01), which remained significant after multiple comparisons. Specifically, incident MCI participants started their surveys 159 minutes later than stable cognitively intact participants, after adjusting for covariates. The linear mixed effects model for adherence revealed a significant main effect of group; incident MCI participants submitted fewer forms (three fewer per quarter) than stable cognitively intact participants (β = −2.86, SE = 1.37, t = −2.1; p=0.04). This effect was not significant after controlling for multiple comparisons.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal Change in Survey Completion Time (in seconds) by Group in the 12 month period before MCI diagnosis (calculated regression lines from the mixed effect model)

Discussion

Using a computer to go online is a cognitively complex IADL that is becoming increasingly common in the older adult population. In this study, we demonstrated that frequently measured online survey metadata allowed for detection of cross-sectional group differences (Incident MCI and stable cognitively intact) and longitudinal within-person IADL changes. Cross-sectionally, three months of baseline weekly online survey metadata were able to effectively discriminate between incident MCI older adults and stable cognitively intact. The FAQ, an IADL questionnaire used widely in AD research (such as the ADNI study), was unable to discriminate between the two groups at baseline. The most sensitive online survey metric observed in the cross-sectional comparison was the time of day that the online survey was completed, which yielded a medium effect size.

Importantly, our data suggest that the time of day older adults’ complete cognitively demanding IADLs may be relevant to development of MCI. One interpretation is that declining cognitive abilities contribute to cognitively demanding tasks such as going online to complete a survey becoming more easily forgotten and vulnerable to postponement until later in the day. An alternative explanation is low mood or depression; however, there were no baseline differences in mood or depression between incident MCI and stable cognitively intact participants. Work is underway to examine if incident MCI is associated with completing other IADLs later in the day, particularly tasks that are central to maintaining one’s health and independence (e.g., medications, driving).

As anticipated, our online survey metadata metrics were significantly associated with traditional neuropsychological test scores. Specifically, later online survey start time of day was associated with poorer memory and visual-spatial abilities. In contrast, the online survey metrics were not significantly associated with an informant rated IADL questionnaire. This highlights the multiple interrelated cognitive requirements of actual computer use (and online survey completion) that are impossible to capture by informant-report of IADLs. Results from the current study are congruent with the cognitively mediated model of everyday functioning26, suggesting that IADL performance is multi-dimensional and is mediated by global and cognitive domain specific factors. Continuous monitoring of IADL activities in one’s home environment permits natural examination of cognitive skills required for efficient daily function that are not easily assessed in a structured clinic environment via conventional tools, such as remembering to begin a task, sustaining effort, performing in the context of and/or inhibiting distractions, and persisting until completion. Thus, remote continuous monitoring of actual IADL activities may provide more sensitive measures of developing MCI than less precise IADL questionnaire measures.

Longitudinal analysis revealed that after controlling for age, education, and multiple comparisons, we found that overall, incident MCI individuals completed their surveys later in the day than stable cognitively intact participants (similar to the cross-sectional comparisons). Regardless of diagnostic group membership, over time slower survey completion time was associated with older age which could be related to normal age-related slowing and decreases in processing speed. Most intriguing was our interaction finding that incident MCI participants showed an increase in their survey completion time in minutes over the one year period (slope) prior to diagnosis compared to stable cognitively intact participants in their last one year period of monitoring. This finding is consistent with literature demonstrating that decreased speed and efficiency in which daily activities are completed, above and beyond normal age-related slowing in speeded processing, may be an early indicator of MCI 8. Mild cognitive difficulties might drive slower survey completion in participants who later develop MCI; for example, forgetting dates or details of an item endorsed could result in having to take additional time to fill out the required text box and drop down calendar. The repeated questions and overall format of the survey could also tend to be less well remembered and more difficult to navigate from week to week.

Our longitudinal findings are in line with recent studies showing that complex IADL functioning is a sensitive marker of developing MCI3, while further showing that IADL markers for MCI can be assessed unobtrusively and routinely in the home environment. During the transition from normal aging to MCI, the initiation and execution of complex daily tasks such as computer use may gradually become less efficient and effective (as detected by our online survey metadata metrics) until noticeable functional impairment is detectable via conventional assessment tools. Our online survey is brief, self-administered, conducive to weekly assessment, and accessible to the wider scientific community through commercially available software. Future clinical research applications of continuous in-home IADL monitoring include incorporating such tasks into longitudinal research protocols, widespread screening, or clinical trials alongside traditional neuropsychological tests to monitor the progression or regression of clinically relevant functional IADL change in older adults with MCI or who are at risk for MCI. Remotely monitored continuous in-home IADL assessment may be particularly useful for older adults who live in rural areas and for who comprehensive testing may not be practical or feasible.

The current conclusions need to be interpreted in light of several limitations. The cohort is a homogenous convenience sample of predominately Caucasian (80%), well-educated volunteers living in a metropolitan area who have very low levels of depression and health co-morbidities. They were computer users or trained to use computers to take part in this study which originally began in 2007. This reduces the generalizability of our findings to more diverse samples of older adults who may have more health problems, live in rural areas, and have lower education, socioeconomic status, and uptake or use of everyday technologies. The sample size of incident MCI was relatively small which may have limited our power to detect differences between groups. We did not have access to traditional biomarker data in this study. Future longitudinal studies will be aimed at replicating these results with larger and more heterogeneous samples of older adults to provide more definitive and generalizable data.

Baseline global cognitive z-scores were more sensitive at discriminating between incident MCI and stable cognitively intact participants than our baseline online survey metadata; thus, it was not included as a covariate in our statistical models. Passive online survey taking measures as indicators of change should be not be considered as stand-alone substitutes for traditional psychometric tests in differentiating MCI verses non-MCI patients. The new metrics are best considered as providing a means to detect cognitive change mediated through everyday functional activities in an ecologically relevant way that could supplement and provide converging data with formal cognitive testing. Thus the online survey assessment is best thought of as a measure of “everyday cognition” that may indicate the beginning of higher order functional decline mediated through existing cognitive capacities that are also demonstrated through more formal cognitive tests over time, a relationship that we have demonstrated in this study.

Research in Context.

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional (e.g., PubMed) sources and meeting abstracts and presentations. While subtle changes in everyday activities may accompany the onset of mild cognitive decline, these changes are difficult to measure with conventional clinical assessments. There have been several recent publications describing a novel in-home activity monitoring paradigm for assessing instrumental activities of daily living including computer use. These relevant studies are appropriately cited. Interpretation: Our findings demonstrated that weekly observations of task performance obtained through home-based activity monitoring allowed for detection of subtle cognitive changes before transition to MCI. Future directions: The manuscript proposes a novel approach for unobtrusive assessment of everyday cognition using an online task and algorithms that can be easily embedded in longitudinal protocols. This approach may lead to the identification and characterization of a behavioral signature predictive of transition from cognitively normal to MCI in older adults.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Alzheimer’s Association grant NIRG-15-362233 and National Institutes of Health grants AG024978, AG024059, and AG023477, P30AG008017, and AG042191. The authors have no potential conflict of interest with this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jedynak BM, Lang A, Liu B, et al. A computational neurodegenerative disease progression score: method and results with the Alzheimer’s disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort. Neuroimage. 2012;63:1478–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Galasko DR, Salmon DP, Bondi MW Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Subtle Cognitive Decline and Biomarker Staging in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2015;47:231–242. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarnanas I, Tsolaki A, Wiederhold M, Wiederhold B, Tsolaki M. Five-year biomarker progression variability for Alzheimer’s disease dementia prediction: Can a complex instrumental activities of daily living marker fill in the gaps? Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2015;1:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verlinden VJ, van der Geest JN, de Bruijn RF, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Ikram MA. Trajectories of decline in cognition and daily functioning in preclinical dementia. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2016;12:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodge H, Zhu J, Harvey D, et al. Biomarker progressions explain higher variability in stage-specific cognitive decline than baseline values in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2014:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Dodge H, Kaye J, Zhu J, Mattek N, Kornfield J. Use of intra-individual distributions of daily acquired home-based measures increases rct sensitivity. PLOS ONE. 2014;10(Supplement):P204. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodge HH, Zhu J, Mattek NC, Austin D, Kornfeld J, Kaye JA. Use of High-Frequency In-Home Monitoring Data May Reduce Sample Sizes Needed in Clinical Trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jekel K, Damian M, Wattmo C, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and deficits in instrumental activities of daily living: a systematic review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:17. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malinowsky C, Almkvist O, Kottorp A, Nygard L. Ability to manage everyday technology: a comparison of persons with dementia or mild cognitive impairment and older adults without cognitive impairment. Disability and rehabilitation Assistive technology. 2010;5:462–469. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2010.496098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seelye A, Mattek N, Howieson DB, et al. Embedded Online Questionnaire Measures Are Sensitive to Identifying Mild Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2016;30:152–159. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons BE, Austin D, Seelye A, et al. Pervasive Computing Technologies to Continuously Assess Alzheimer’s Disease Progression and Intervention Efficacy. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2015;7:102. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seelye A, Hagler S, Mattek N, et al. Computer mouse movement patterns: A potential marker of mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2015;1:472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seelye A, Kaye J, Austin J, et al. Ecologically Valid Assessment of Life Activities: Unobtrusive Continuous Monitoring with Sensors. The Alzheimer’s Association International Conference; Toronto, Canada. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seelye A, Mattek N, Howieson D, et al. Embedded online questionnaire measures are sensitive to identifying mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s Disease & Associated Disorders. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000100. Epub ahead of print, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes TL, Larimer N, Adami A, Kaye JA. Medication adherence in healthy elders: small cognitive changes make a big difference. Journal of aging and health. 2009;21:567–580. doi: 10.1177/0898264309332836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaye J, Mattek N, Dodge HH, et al. Unobtrusive measurement of daily computer use to detect mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2014;10:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaye JA, Maxwell SA, Mattek N, et al. Intelligent Systems For Assessing Aging Changes: home-based, unobtrusive, and continuous assessment of aging. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2011;66(Suppl 1):i180–190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith A. Older Adults and Technology Use [online] Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/03/older-adults-and-technology-use/

- 19.Liu-Seifert H, Siemers E, Selzler K, et al. Correlation between Cognition and Function across the Spectrum of Alzheimer’s Disease. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2016.99. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jak AJ, Bondi MW, Delano-Wood L, et al. Quantification of five neuropsychological approaches to defining mild cognitive impairment. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17:368–375. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819431d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linn B, Linn M, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1968;16:622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Craen AJ, Heeren TJ, Gussekloo J. Accuracy of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) in a community sample of the oldest old. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2003;18:63–66. doi: 10.1002/gps.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. Journal of gerontology. 1982;37:323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bondi MW, Edmonds EC, Jak AJ, et al. Neuropsychological criteria for mild cognitive impairment improves diagnostic precision, biomarker associations, and progression rates. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2014;42:275–289. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farias ST, Park LQ, Harvey DJ, et al. Everyday cognition in older adults: associations with neuropsychological performance and structural brain imaging. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 2013;19:430–441. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]