Abstract

The importance of basing public policy on sound scientific evidence is increasingly being recognized, yet many barriers continue to slow the translation of prevention research into legislative action. This work reports on the feasibility of a model for overcoming these barriers—known as the Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC). The RPC employs strategic legislative needs assessments and a rapid response Researcher Network to accelerate the translation of research findings into usable knowledge for policymakers. Evaluation findings revealed that this model can successfully mobilize prevention scientists, engage legislative offices, connect policymakers and experts in prevention, and elicit congressional requests for evidence on effective prevention strategies. On average, the RPC model costs $3,510 to implement per legislative office. The RPC can elicit requests for evidence at an average cost of $444 per request. The implications of this work, opportunities for optimizing project elements, and plans for future work are discussed. Ultimately, this project signals that the use of scientific knowledge of prevention in policymaking can be greatly augmented through strategic investment in translational efforts.

Keywords: Evidence-Based Policy, Preventive Intervention, Translational Research, Cost-Effectiveness, Use of Evidence

Increasing efforts to support the use of scientific knowledge to inform policymaking have resulted in a policy climate being referred to as a ‘golden age of evidence-based policy’ (Association for Public Policy and Management, 2015; Haskins & Margolis, 2015). While this contrasts with images of policymaking portrayed in popular media and held by the public, the reality is the use of evidence remains a bipartisan issue (Mason & Shelton, 2016; Milner, 2016). Evidence-based policymaking is characterized by legislative and regulatory efforts to scaffold public spending in a manner that relies on epidemiological, etiological, and intervention research findings (Aos, Miller, & Drake, 2006; Baron & Haskins, 2011; Crowley, 2013). For instance, policymakers have increasingly used tiered evidence initiatives that predicate public spending for different social programs on attaining certain thresholds of empirical evidence (e.g., impacts found within randomized controlled trials, replication, large-scale studies; Haskins & Margolis, 2015). Despite early successes, many opportunities to incorporate prevention science into policy have yet to be realized (Crowley & Jones, 2015; Fishbein, Ridenour, Stahl, & Sussman, 2016; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). This is particularly concerning considering the growing evidence that social and behavioral prevention strategies can improve health and save public resources (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016; O’Connell, Boat, & Warner, 2009).

Yet the process of deploying scientific evidence from peer-reviewed literature to guide legislative efforts remains unclear (Biglan, 2016; Ginexi, 2006), in part because the science of using research findings in policy remains limited (Fishbein et al., 2016). A number of factors contribute to the slow translational process. These include limited efforts to synthesize and distill research into usable forms, limited legislative capacity for translating research, researchers’ limited understanding of the legislative process, and relatively few productive relationships between researchers and legislative offices (Crowley & Jones, 2015; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016).

This work reports on the findings from a pilot project, evaluating the feasibility of a translational model for overcoming barriers to the use of research in policy by cultivating researchers’ capacity for rapid response to legislative needs. This pilot reflects the first implementation of this translational model – its structure, methods, and necessary resources for engaging legislative offices are outlined below. Findings from evaluation of the model’s costs, impacts and cost-effectiveness are described.

Increasing the Use of Prevention Evidence in Policymaking

One of the greatest needs noted in translational literature is for improved access to research that has been translated for policymakers and practitioners (Oliver, Innvær, Lorenc, Woodman, & Thomas, 2014). Such information has the potential to increase policymakers’ awareness of the utility of evidence-based prevention for achieving budgetary, public health, education, and workforce goals (Biglan, 2016; Crowley, Jones, Coffman, & Greenberg, 2014; Fishbein et al., 2016;). However, the transfer of this information is not carried out in a vacuum; interpersonal trust and relationships guide policymakers’ inquiries, acquisition, and use of information for legislation (Foa, Gillihan, & Bryant, 2013; Meyer, 2010). As such, policymakers frequently rely on trusted colleagues and advisors to inform their decisions (Brownson, Haire-Joshu, & Luke, 2006; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016; Oliver, Lorenc, & Innvær, 2014).

Although expert credentials aid in policymakers’ receptivity to scientific evidence, their receptivity is also affected by the perceived transparency, honesty, and impartiality of the information source (Brownson et al., 2006; Fox, 2005). In fact, mutual mistrust and a lack of personal contact between researchers and policymakers are prominent barriers to the use of research by policymakers (Choi et al., 2005; Oliver, Innvær, et al., 2014). Much of the mistrust is driven by a lack of understanding and respect for one another’s professional cultures and values (Aarons, Hurlburt, & Horwitz, 2011; Brownson et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2005). For example, elected officials must be responsive to constituents and many interest groups, of which scientists comprise only one (Brownson et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2005; Haskins & Margolis, 2015). In this context, training researchers about the culture within public policy environments may help them better interact with government officials. Moreover, providing opportunities for interaction is expected to enhance trust and information transfer between parties (Beck, Gately, Lubin, Moody, & Beverly, 2014; Brown, Feinberg, & Greenberg, 2010).

Identifying policymakers’ most pressing needs and facilitating collaboration with researchers to develop policy recommendations can aid the use of research in policy (Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Bowen & Zwi, 2005; Choi, 2005; Cummings & Williams, 2008). However, successful collaboration requires substantial time investment by both prevention experts and legislative offices (Foa et al., 2013). This is challenging because the primary occupation of many researchers does not incentivize policy engagement. Further, many researchers have concerns about their capacity to engage with policymakers and respond to legislative needs in a timely fashion (Biglan, 2016; Dobbins et al., 2009). In addition to the scientific community, legislators and their staff experience tremendous demands on their time from many other competing constituencies (Vandlandingham & Silloway, 2015). This requires that researchers engage in nonpartisan and unbiased communication about the state of scientific knowledge (Fishbein et al., 2016; Meyer, 2010) because lobbying for specific legislation or resources (sometimes prohibited by organizations and institutions) can easily undercut the legislative audiences’ trust in experts and willingness to use evidence for policymaking (Dobbins et al., 2009).

While there are multiple legislative advocacy approaches, there is a need for a science translation model that mobilizes researchers to connect with policymakers in ways that support the desire to use evidence in decision making (Oliver, Lorenc, et al., 2014; Vandlandingham & Silloway, 2015). Additionally, many translational strategies emphasize supply-side, producer-push models (e.g., synthesizing research prioritized by prevention scientists) rather than recognizing the needs and demands of the end-user (Tseng, 2012). In contrast, other translational strategies emphasize policymakers’ needs, but are limited to research synthesis (e.g., Khangura, Konnyu, Cushman, Grimshaw, & Moher, 2012). Overall, there are few well-defined strategies available to mobilize prevention experts for translating research with legislative audiences, and none have been evaluated for their potential cost-effectiveness (Choi et al., 2005).

The Research-to-Policy Collaboration Model

In response to the need for a formal model for translating prevention research, the Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC) model was developed to accomplish three primary goals: (1) mobilizing prevention scientists’ engagement with legislative offices, (2) connecting legislative offices with prevention researchers, and (3) eliciting requests for prevention-oriented evidence for policymaking. The RPC can be implemented by membership-based, intermediary organizations (e.g., professional societies, non-profit agencies and large multidisciplinary academic institutes), which play a critical role in evidence-based policy and can broker relationships between researchers and decision makers (National Research Council, 2012; Tseng, 2012). Moreover, a membership network allows an intermediary organization to map research expertise among individuals with which they are currently connected.

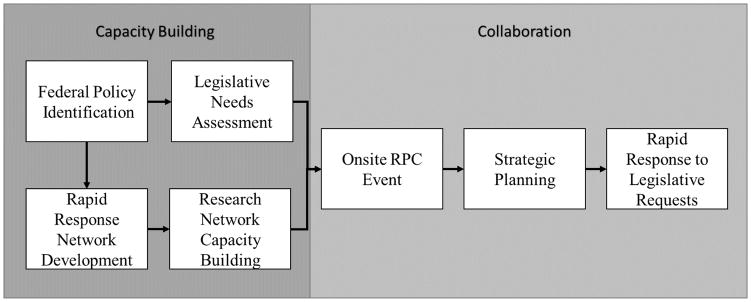

The RPC model leverages connections in both research and policy arenas to employ a multistep process for bridging research and policy. RPC implementation occurs after an intermediary has conducted an initial assessment of policy opportunities relevant to their substantive focus. Similar to Kingdon’s (1984) notion of the policy window, this assessment considers current legislative efforts and interests, as well as the capacity of the intermediary’s membership network to respond to legislative priorities with relevant scientific information. In this way, the RPC is adaptive to the needs and interests of legislators and policy opportunities. After this initial assessment, the RPC is largely implemented by a Project Coordinator. Implementation steps include: (1) identification of federal policy issues; (2) development of a rapid response Researcher Network; (3) building Network capacity; (4) assessment of legislative needs; (5) holding a rapid response Team event; (6) strategic planning for response; and (7) rapid response to legislative requests (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research-to-Policy Model for Translating Prevention Research

Federal policy identification

The RPC Coordinator engages in initial outreach to legislative experts and staff around priority areas for the congressional session. These priorities are elicited through a semi-structured needs assessment protocol, which asks (1) how would you like to strengthen prevention of a specific problem, (2) how might researchers or practicing consultants be of value to your work, and (3) in what ways might your work have implications for future research? The needs assessment engages staffers in conversation rather than operating like an impersonal interview, and follow-up questions are asked based on initial responses.

Develop rapid response Researcher Network

First, membership records from an intermediary organization (i.e., National Prevention Science Coalition, Prevention Economics Planning & Research Network and Society for Prevention Research) are used by the RPC Coordinator to invite researchers with relevant expertise to join a Research Network. Those willing to join are asked to submit additional information about their experience, level of commitment, and expertise in previously identified federal policy areas. This allows the RPC Coordinator to engage in a strategic resource mapping process, which results in an inventory that catalogues researchers’ core areas of expertise and their willingness to and experience with engaging with federal policymakers.

Build Network capacity

Few scientists have received formal training on the legislative process and/or legislative outreach strategies, or how to translate their work for a legislative audience (Biglan, 2016; Dobbins et al., 2009). The RPC Coordinator supports researchers’ capacity development through a web-based training series and structured opportunities for policy engagement. The training aims to increase competencies related to policy engagement and interactions with legislative personnel, and is comprised of one-hour sessions delivered over a six-week period. Sessions include (1) introduction to the RPC model, (2) developing trusting relationships with congressional offices, (3) engaging in the legislative process, (4) avoiding behaviors that violate lobbying regulations, (5) knowledge brokering with a role play exercise, and (6) developing a strategic plan for collaboration. Additionally, the RPC Coordinator engages the Network in responding to legislative requests, which allows participants to apply training lessons and receive constructive support from the RPC Coordinator to strengthen the impact of their research translation efforts.

Assess legislative short-term needs

Current legislative needs and priorities are tracked through a second semi-structured needs assessment that the RPC Coordinator conducts with legislative staff. This assessment (1) revisits what was previously discussed regarding the legislator’s priorities, (2) asks which specific issue the legislator would prefer to prioritize for rapid response, and (3) solicits specific suggestions or requests regarding how a team of research experts might support the legislator’s efforts. Compared to the policy identification step, this needs assessment establishes the focus of the rapid response and is more action-oriented regarding specific activities through which researchers might support legislative efforts. This process should be carried out within one month prior to completing the rapid response Team event to adapt to policymakers’ real-time priorities, a known facilitator to the use of evidence in policy (Oliver Innvær, et al., 2014). Furthermore, understanding the most current priorities enables the Coordinator to forge connections between legislative offices and researchers who have the most relevant expertise.

Hold rapid response Team event

Because direct interactions to discuss research can reinforce relationships deemed necessary for advancing evidence-based policy (Dobbins et al., 2009), the RPC involves face-to-face meetings between rapid response team members and legislative staff. Additionally, deliberation during meetings can support the development of implications, as research interpretation is a formative and iterative process (National Research Council, 2012; Tseng, 2012). The team travels to Washington, DC to: (1) respond to initial legislative requests, (2) interpret research based on the current need, and (3) plan for next steps supporting legislative offices. This event includes meetings with individual staff, meetings with multiple staffers, meetings with committee staff and members, as well as informal social gatherings with researchers, staff, and congressional members. Researchers meeting in person with congressional offices are selected based on participation in trainings, demonstrable willingness to engage in rapid response, expertise related to the office’s interests, and common geographic location (i.e., same congressional district as congressional member).

Strategic planning for response

Immediately following the event day’s meetings, strategic planning for rapid response is facilitated by the RPC Coordinator with Rapid Response Team members. The strategic planning approach draws upon models for public relations, communication and healthcare triage models (Hans, Erwin, van Houdenhoven, & Hulshof, 2012; Smith, 2013). RPC staff and participating research experts meet to summarize goals and objectives, determine next steps, and identify point person(s) for following up with each office. Legislative requests are ordered based upon priority status and when they are needed by the congressional office. This plan is used to guide the subsequent rapid response.

Rapid response to legislative requests

Following the event, legislative requests are addressed by the Research Network (both those in attendance and those not). Responses are triaged to prioritize those that are needed immediately. Rapid response procedures may include: (1) collecting and summarizing relevant resources for offices, (2) soliciting professional networks for consensus on topics or information on more obscure requests, (3) planning congressional briefings to be sponsored by the congressional office, or (4) supporting congressional hearings that include researcher testimony. Key is the collaborative nature of this process both with the office as well as among the interdisciplinary group of researchers. Evidence requested by offices often spans disciplinary boundaries and requires not only knowledge of the state of the science, but also an ability to determine when it is appropriate to generalize that work to settings of interest to legislative offices.

Methods

Prior to implementing the RPC model, a number of federal policy efforts related to criminal justice reform were underway. These priorities were driven, in part, by the growing awareness of fiscal and social implications from mass incarceration and other punitive approaches. These policy opportunities and the content expertise of members in the organization’s network led the current effort to focus on criminal justice, including policy priorities related to juvenile justice and prison practices.

The evaluation of the RPC model included a cost analysis of implementation, an impact analysis of the three primary model goals (prevention scientists’ legislative engagement, fostering legislative-researcher connections, and eliciting requests for evidence), and a cost-effectiveness analysis of the resources needed to produce incremental levels of impact. This pilot employed a mixed methods approach to evaluate the model’s resource consumptive activities and impacts. Multiple sources of information were mined for data. Key goals included understanding the model’s use of resources and considering ways to optimize its potential value for accelerating use of evidence in policymaking. The pilot period spanned 230 days, during which the seven core model activities described above were accomplished.

Sample

The RPC model is a multi-level intervention that separately targets prevention research experts and legislative offices before bringing these parties together for collaboration.

Legislative offices

Legislative offices include elected officials and congressional staff. Each office is led by either a Senator or a House Representative. At the time of the pilot, the 114th Congress was comprised of elected officials whose average age was 59. Among sitting members, 20% were female and 18.5% were non-White. Nearly all sitting members held a bachelor’s degree (94% of House, 100% of Senators), 64–74% had educational degrees beyond a bachelor’s (e.g., 213 JDs, 15 MDs, 24 PhDs). Congressional staff engaged within the RPC pilot included personal staff (hired by a member of Congress) and committee staff (hired by a chairman or ranking member of a committee). The pilot did not seek to engage institutional or support agency staff who are generally unaffiliated with legislative offices. While the RPC primarily engaged one staff in each participating office, the average representative’s offices had 14 congressional staff and the average Senator had 30 staff. Participating Congressional staffers tended to be male (68%) and White (93%), and all had bachelor’s degrees. Almost 50% of staffers had worked on Capitol Hill for less than 10 years and most made between $30,000 and $50,000 a year. RPC staff contacted 21 offices to initiate the RPC model implementation. Of those 21, 10 agreed to participate in the RPC (6 Republicans and 4 Democrats).

Prevention experts

Experts in prevention research, including researchers and practitioners from both academic and nonacademic settings, were also engaged in the RPC to facilitate translation of science to policy. This included training, connecting with legislative offices, and supporting participation on rapid response teams. In this pilot, the criteria for participation within the RPC training were: (1) a stated interest in engaging with federal policymakers, (2) declared expertise in at least one related area of prevention, and (3) substantive knowledge related to the identified federal policy issue. Twenty-nine prevention experts joined the rapid response network, and 22 participated in at least one training. Of those trained, 57% were from academic institutions. Nine experts participated in the rapid response event to meet with congressional offices – 55.6% were female and 11% were non-White. Most participants had earned a Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) and were trained in psychology (e.g., developmental, school, and clinical psychology), though one participant had earned a Juris Doctorate, and another had earned a Master’s degree in public health. On average, participants earned their highest degree 17.4 years (SD = 11.45) prior to RPC involvement and currently earned an average of $75,625 (SD = $18,275) per year.

Cost Analysis

An ingredients-based cost analysis was employed to quantify and value the resources consumed by implementing the RPC model. The cost analysis tracked all resources consumed during the pilot period (Crowley et al., 2012; Levin & McEwan, 2000). Project budgets were coded for different types of resource consumption (e.g., personnel, materials, travel, lodging and food). To estimate costs, personnel time (including RPC implementation, administrative tasks, and travel) was tracked in 15-minute increments time-stamped with date and time of day. Pennsylvania State University’s fringe rate of 40.2% of staff salary was applied to these cost estimates. Resource utilization on non-personnel expenditures was tracked through an activity-based costing procedure to attribute all costs to specific resource-consumptive activities (Ben-Arieh & Qian, 2003). All non-personnel costs were time-stamped (e.g., researcher and staff travel, meeting costs, materials). In-kind and volunteer resources were tracked for multiple sources (e.g., staff, prevention experts and existing infrastructure). As is best practice, sensitivity analyses considered variability in the quantity of resources and market value where appropriate to develop confidence intervals around all estimates (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). Specifically, while the time spent by RPC personnel were closely tracked, the price at which this time is valued is likely to vary across site and context. To consider this variation and examine the robustness of estimates, personnel compensation was varied within reasonable ranges for individuals capable of implementing the RPC model.

Impact Analysis

The pilot of the RPC model sought to assess whether it could be used to successfully (1) mobilize prevention experts to engage with legislative offices, (2) connect legislative offices with prevention researchers, and (3) elicit requests for prevention-oriented evidence for policymaking. To track RPC model primary outcomes, all correspondence with researchers and legislative offices was tracked and documented (email, calls and in-person meetings).

Mobilizing prevention scientists

The RPC model’s ability to mobilize prevention scientists’ engagement with legislative offices was measured based upon the number of hours prevention scientists engaged in RPC activities for both preparing to meet with offices (training, planning meetings, direct interaction [in-person and virtual]) and engaging in follow-up contacts in response to legislative requests during the pilot period. Time was tracked using records of duration of RPC meetings with prevention scientists.

Connecting legislative offices and prevention experts

The RPC’s second goal of connecting legislative offices with prevention researchers was measured based on the number of hours of shared contact. This included both in-person and telecommunications (i.e., telephone or web conferencing). Connection included time spent on policy issue identification, needs assessment, rapid response event, and follow-up responses. Time was tracked based upon duration of RPC meetings with legislative offices using professional time tracking software. This represents a conservative measure of legislative office investments since time spent outside of meetings, such as writing email, reading materials, or discussing evidence raised by prevention experts was not included in time estimates.

Eliciting legislative requests for prevention-oriented evidence

The RPC model’s ability to elicit legislative requests was tracked based upon requests made during in-person or virtual meetings. Requests were defined as distinct solicitations for information, summaries of primary evidence from prevention research, or framing issues around a prevention orientation (e.g., upstream investment, targeting risk and protective factors, early intervention, avoidance of future harm or cost). Requests were recorded in meeting notes by research personnel (not active participants in the RPC model pilot study). Seven types of legislative requests for evidence were considered. These included requests to (1) review preventive intervention strategies (e.g., cost-effectiveness of community-based programs that divert delinquent youth from the justice system), (2) summarize etiologic evidence (e.g., antecedents and mechanisms of delinquent behavior), (3) identify likely prevention impact on public systems (e.g., fiscal impacts if implementing interventions at scale), (4) support analysis of administrative data (e.g., state variability in juvenile sentencing), (5) prepare a policy brief (e.g., alternatives to incarcerating low-risk juvenile offenders), (6) review legislative language (e.g., expected impact of a bill to reform prison sentencing and recidivism reduction efforts), and (7) hold a congressional briefing or support a legislative hearing (e.g., how drug courts may support the rehabilitation of criminal offenders addicted to opiates). Requests not directly related to a need or desire for scientific evidence were not considered evidence requests for the purposes of this evaluation (e.g., requests to connect with other offices).

Cost-Effectiveness Analyses

Cost-Effectiveness Analyses (CEA) are used to contextualize the impacts of an intervention in terms of the resources needed to achieve an effect (Levin & McEwan, 2000). CEA is particularly useful when preserving the natural unit of the outcome(s) of interest (Brouwer, Koopmanschap, & Rutten, 1997). For this evaluation, we considered the cost-effectiveness of mobilizing prevention experts, connecting with legislative offices, and eliciting requests for prevention evidence. Specifically, the cost of producing each unit of an outcome was calculated (i.e., hour of prevention expert time, hour of legislative office time and request for evidence). This calculation resulted in the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for each of the three outcomes. An ICER considers the quotient of the difference between an intervention and an alternative prevention strategy’s cost and effect. The comparator for the current analyses was no delivery of the RPC.

Where i is the intervention of interest and c is the comparator prevention strategy. ICERs that consider the same outcome can be used to compare the same program and assist in decision-making when considering responses to specific problems. These analyses can be useful in planning and resource allocation decisions. Importantly, they answer common questions posed by policymakers and budget writers (Hoffmann et al., 2002;).

Results

RPC model costs

Implementation of the RPC model cost on average $3,510 (CI = $3,164–$4,519) per office served (Table 1). This included $2,141 (CI = $1,795–$3,150) in personnel costs, $1,314 in event and travel costs, and $54 in materials costs. The onsite event consumed half the RPC model costs (50%). The rapid response to legislative requests was the second largest category, consuming 21% of the total resources. The resources needed to develop the rapid response researcher network and build its capacity were relatively small, consisting of less than $2,500 combined for all 10 offices served (7%). The largest single driver of cost was the travel and lodging of researchers to Washington, DC for meetings with legislative staff.

Table 1.

RPC Model Implementation Costs

| Coordinator (Hours) | Coordinator (Cost) | Supervisor (Hours) | Supervisor (Cost) | Materials | Travel, Lodging and Food | Total | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identify Federal Policy Issue | 72 | $2,362 | 2 | $200 | $100 | $638 | $3,301 | $2,986–$3,852 |

| Develop Rapid Response Network | 14 | $462 | 2 | $200 | $662 | $520–$810 | ||

| Build Network Capacity | 58 | $1,928 | 5 | $500 | $40 | $2,468 | $2,043–$3,002 | |

| Assess Legislative Office Needs | 60 | $1,972 | 1 | $100 | $100 | $1,332 | $3,504 | $3,274–$3,947 |

| Hold Rapid Response Team Event | 129 | $4,260 | 19 | $1,850 | $300 | $11,075 | $17,484 | $16,172–$18,850 |

| Strategic Planning for Response | 3 | $83 | 1 | $100 | $103 | $286 | $228–$328 | |

| Response to Legislative Requests | 200 | $6,600 | 8 | $800 | $7,400 | $6,400–$9,000 | ||

| Total | 535 | $17,666 | 38 | $3,750 | $540 | $13,148 | $35,104 | $31,623–$39,789 |

| Average Per Office | 54 | $1,767 | 4 | $375 | $54 | $1,315 | $3,510 | $3,162–$3,979 |

RPC model impact

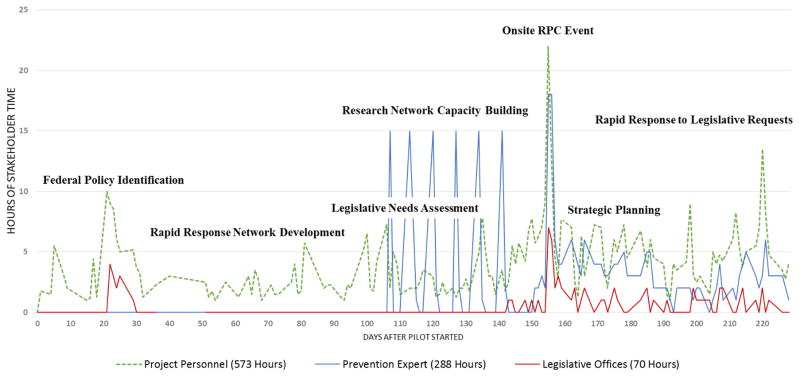

Within this pilot, the RPC model was able to achieve its three primary goals of (1) mobilizing prevention scientists’ engagement with legislative offices, (2) connecting legislative offices with prevention researchers, and (3) eliciting requests for prevention-oriented evidence for policymaking. The RPC model mobilized 288 volunteer hours (M = 14.4) of prevention scientists’ time to receive training, engage with legislative offices around their area of expertise, and respond to legislative requests (Figure 2). Implementation of the RPC model resulted in 70 hours (M = 7.0) of direct interaction between the RPC Coordinator and 10 legislative offices on the use of evidence from prevention research (Figure 2). Finally, the RPC model elicited a total of 79 (M = 7.9) unique requests for prevention evidence in the form of literature reviews, policy briefs, hearing support, holding of congressional briefings, and review of proposed legislative language (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Stakeholder Time Across RPC Implementation

Note: This figure descibes the number of hours invested in the RPC model over the course of implementation by the three stakeholder groups (i.e., prevention experts, legislative offices and project personnel). Additional labels embedded in the figure indicate the general period during which the seven RPC steps were undertaken highlighting enagement of different stakeholder groups and overlap in the RPC process.

Table 2.

Frequency of Legislative Requests for Prevention-related Evidence

| Request Type | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Review Preventive Intervention Strategies | 29 | 37% |

| Summarize Etiologic Evidence | 18 | 23% |

| Identify Likely Prevention Impact on Public Systems | 15 | 19% |

| Support Analysis of Administrative Data | 5 | 6% |

| Prepare Policy Brief | 5 | 6% |

| Review Legislative Language | 4 | 5% |

| Hold Congressional Briefing or Support Hearing | 3 | 4% |

| Total Requests | 79 |

RPC model cost-effectiveness

These cost and impact estimates allowed us to calculate the cost-effectiveness of the model for federal legislative engagement (Table 3). Three cost-effectiveness measures were computed by dividing total cost by (1) number of prevention scientist hours mobilized, (2) number of hours of legislative staff time, and (3) number of legislative requests received. In this context, the RPC model was able to mobilize an hour of a prevention expert’s time for an average of $122 (CI = $110–$138). Separately, the RPC model was able to connect prevention researchers to legislative offices for an average cost of $502/hour (CI = $452–$568). On average, the RPC model cost $444 (CI = $400–$572) to elicit a request from a legislative office for prevention evidence. When considering these three outcomes together, every $888 spent on the RPC mobilized 7.3 hours of prevention scientist time, 1.8 hours of legislative office time and elicited 2 requests for scientific evidence.

Table 3.

Incremental Cost-Effectiveness of the RPC Model

| Outcome | Total Outcome Produced | Total RPC Costs | ICER | Confidence Inteval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobilize Prevention Experts | 288 Hours | $35,100 | $122 | $110–$138 |

| Connect with Legislative Offices | 70 Hours | $35,100 | $502 | $452–$568 |

| Elicit Requests for Evidence | 79 Requests | $35,100 | $444 | $400–$572 |

Note: ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Legislative office impact

Legislative offices received an average of 29 hours of prevention experts’ time worth an average $1,113 based upon expert’s compensation in their primary occupation. Additionally, they received an average of $23 in materials. During the course of rapid response, 192 resources were located and distributed to offices.

Prevention researcher impact

Researchers were affected by participation in the model in a number of ways. In particular, the RPC model invested an average of $157 per researcher in coalescing and training the rapid response network (N = 20). For those selected to participate in the Rapid Response Team event, the RPC model invested an additional $1,943 on average per researcher (N = 9). The researchers participating in the research network expended about 6 hours participating in capacity-building efforts. Those who participated in the rapid response event expended an additional 26.7 hours, including direct and indirect contact with legislative offices.

Discussion

The RPC model offers a formal strategy for translating prevention research for policymaking and provides a sustainable approach for engaging in legislative outreach that serves both legislative offices’ and prevention scientists’ needs. This model may be effectively used to mobilize prevention scientists, connect with legislative offices, and elicit clear requests for evidence to be used in the policymaking process. This contrasts with other ‘pipeline’ models of science translation that seek to tell legislative groups about new findings, but often fail to recognize policymakers’ needs and goals (Oliver, Lorenc, et al., 2014; Tseng, 2012).

The RPC’s cost-effectiveness estimates contextualize the value of investing in this model. In particular, the RPC model’s ability to elicit a request for prevention evidence from a legislative office for under $450 provides a useful metric for those considering whether to engage in such outreach. Specifically, few prevention scientists regularly receive requests from federal policymakers for evidence to guide policy or budget decisions. For those individuals, the RPC model may represent a worthwhile investment of their time. Of course, some prevention researchers frequently receive such requests and, consequently, may be less likely to feel that the RPC represents adequate return for its cost (i.e., volunteer time commitment). Either way, we believe that the RPC represents a promising strategy that offers both researchers and legislative offices an infrastructure through which to organize and support the transfer of empirical evidence to policymakers. These estimates set an initial bar the field can strive to surpass—lowering the costs to mobilize experts, engage legislative offices, and elicit evidence requests.

Findings from this work indicate that the benefits from the RPC model are particularly pronounced. The substantial amount of time and attention offices invested in participating in the model (both of which are severely constrained) and number of legislative requests made highlight these offices’ recognition of the Rapid Response Teams as a useful resource. The nonpartisan nature of the RPC, its formal structures, and free access to scientists all likely contributed to this recognition. Initial responses to requests also highlight the value of the RPC model for legislative offices. For instance, one office made a request for a Congressional briefing. The Rapid Response Team worked with the office to identify specific topics and then organized, sponsored, and held the briefing in a House office building. Over 150 individuals registered for the event, and 46 congressional offices were represented.

Limitations

This pilot trial of the RPC model offers important insights into the feasibility and utility of employing formal strategies for translating prevention research to policymakers. Many elements require further study. In particular, the processes and mechanisms underlying the model’s impacts require in-depth evaluation. Further, tracking the impact of the model’s implementation on downstream legislative activity would provide greater insight into the model’s value. Additionally, as this evaluation was part of a pilot trial, we considered a limited set of objective impact measures. Future evaluations should examine additional outcomes, including the experiences of participants and subsequent legislative actions, to fully quantify the model’s impact. Moreover, the results of the pilot evaluation are limited in generalizability; it is uncertain if the cost estimates for the current efforts around criminal justice might be comparable to efforts related to different subject matter, or how the feasibility and costs might differ if the RPC were applied to the state (which has greater jurisdiction over many prevention-oriented service systems) rather than federal level of governance.

While the costs of the RPC model are greater than most individual researchers would typically spend on dissemination efforts, they are not beyond the scope of what could be included within federal research proposals or institutional supports. Despite the potential value of the model, the RPC would benefit from increased optimization and identification of the value of different components. For instance, might additional training of prevention scientists decrease the response time to legislative requests and increase efficiency in producing translational research products (briefs, literature summaries, markup of legislative language)? Would serving a greater number of offices at a time result in efficiencies of scale or might it jeopardize the quality of responses to legislative requests? The RPC would benefit from additional evaluation in line with such questions—including the potential to misuse the model by groups seeking to advance information lacking evidence or misconstrued to support a specific political agenda.

Future Directions

Further evaluation of the impact of the RPC model will require additional implementations in order to replicate and expand results. Key will be identifying opportunities to strengthen the model in multiple domains, beyond criminal justice (e.g., child welfare, health care). Another salient need is to better engage research institutions (e.g., universities) in supporting the travel and time of employees, which could enable a broader pool of researchers to contribute knowledge and skills in policy efforts. Furthermore, many secondary outcomes were noted during the course of the pilot that require further study. For instance, during the course of the Rapid Response Team’s work with two different offices, they recognized overlapping interests. RPC staff connected the two offices and, as a result, a new working relationship was formed to advance a bill regarding the common interest. Additionally, it remains unseen the extent to which the RPC has facilitated enduring engagement among prevention experts with participating legislative offices, or more generally in the policy arena. Future work should explore the duration of relationships, as well as how RPC staff can nurture ongoing working relationships across policy and research arenas. Full evaluation of the mechanisms, as well as secondary outcomes, will require in-depth qualitative interviews with participating offices.

Conclusion

This pilot highlights the opportunities to accelerate translation of prevention research into evidence-based policy. Legislative outreach, already considered by many a core element in the dissemination of research findings (Fishbein et al., 2016; Flay et al., 2005; Gottfredson et al., 2015), represents an important mechanism for achieving meaningful public health impacts from public investments in scientific research. The RPC model offers a formalized approach for translating prevention research into evidence-based policy. This approach is a collaborative strategy combined with capacity-building and strategic needs assessments. In particular, this model builds the infrastructure required to address legislative office needs for rapid response and timely information. Overall, this ongoing work reflects increasing efforts to build the science around not only the creation of evidence, but its use in informing decision-making (e,g,, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded through a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Prevention Economics Planning and Research Network, National Institute on Drug Abuse (R13 DA036339) and support from the Penn State University Social Science Research Institute and Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the prevention scientists and legislative offices that took part in this pilot work. Further, this work was supported by institutional resources from the National Coalition for Prevention Science and Prevention Economics Planning and Research Network. Sponsorship for the implementation of the RPC model also came from the Society for Prevention Science, Society for Community Research and Action, Society for Child and Family Policy and Practice, Child Trends, The American Orthopsychiatric Association, and Paxis. Individuals supporting the RPC model include Neil Wollman, Robin Jenkins, and Bobby Vassar. Additionally, we gratefully acknowledge the participation of the different legislative offices and prevention experts.

a. Funding

This work was supported through a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Prevention Economics Planning and Research Network, National Institute on Drug Abuse (R13 DA036339) and support from the Penn State University Social Science Research Institute and Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

b. Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

D. Max Crowley: No Conflicts of Interest to Report

Taylor Scott: No Conflicts of Interest to Report

Diana Fishbein: No Conflicts of Interest to Report

c. Ethical approval

Not Applicable

d. Informed consent

Not Applicable

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews DA, Bonta J. Rehabilitating criminal justice policy and practice. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2010;16:39–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018362. [Google Scholar]

- Aos S, Miller M, Drake E. Evidence-based public policy options to reduce future prison construction, criminal justice costs, and crime rates (No. Document No. 06-10-1201) Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Association for Public Policy and Management. APPAM 2015 fall research conference: The golden age of evidence-based policy. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.appam.org/events/fall-research-conference/2015-fall-research-conference-information/

- Baron J, Haskins R. The Obama Administration’s evidence-based social policy initiatives: An overview. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.brookings.edu/opinions/2011/1102.

- Beck C, Gately KJ, Lubin S, Moody P, Beverly C. Building a state coalition for nursing home excellence. The Gerontologist. 2014;54(Suppl 1):S87–S97. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh D, Qian L. Activity-based cost management for design and development stage. International Journal of Production Economics. 2003;83:169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A. The ultimate goal of prevention and the larger context for translation. Prevention Science. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0635-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0635-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bowen S, Zwi AB. Pathways to “evidence-informed” policy and practice: A framework for action. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2:e166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer WBF, Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FFH. Productivity costs in cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Economics. 1997;6:511–514. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199709)6:5<511::aid-hec297>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D, Feinberg ME, Greenberg MT. Determinants of community coalition ability to support evidence-based programs. Prevention Science. 2010;11:287–297. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0173-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Luke DA. Shaping the context of health: A review of environmental and policy approaches in the prevention of chronic diseases. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:341–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.\. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BCK. Can scientists and policy makers work together? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2005;59:632–637. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.031765. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.031765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley DM. Building efficient crime prevention strategies considering the economics of investing in human development. Criminology & Public Policy. 2013;12:353–366. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley D, Jones DE, Coffman DL, Greenberg MT. Can we build an efficient response to the prescription drug abuse epidemic? Preventive Medicine. 2014;62:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley DM, Jones DE, Greenberg MT, Feinberg ME, Spoth R. Resource consumption of a diffusion model for prevention programs: The PROSPER delivery system. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley M, Jones D. Financing prevention: Opportunities for economic analysis across the translational research cycle. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2015;6:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0354-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings WK, Williams JH. Policy-making for education reform in developing countries. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Education; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins M, Robeson P, Ciliska D, Hanna S, Cameron R, O’Mara L, … Mercer S. A description of a knowledge broker role implemented as part of a randomized controlled trial evaluating three knowledge translation strategies. Implementation Science. 2009;4:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein DH, Ridenour TA, Stahl M, Sussman S. The full translational spectrum of prevention science. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2016;6:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0376-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Biglan A, Boruch RF, Castro FG, Gottfredson D, Kellam S, … Ji P. Standards of evidence: Criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prevention Science. 2005;6:151–175. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Gillihan SJ, Bryant RA. Challenges and successes in dissemination of evidence-based treatments for posttraumatic stress: Lessons learned from prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2013;14:65–111. doi: 10.1177/1529100612468841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DM. Evidence of evidence-based health policy: The politics of systematic reviews in coverage decisions. Health Affairs. 2005;24:114–122. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginexi EM. What’s next for translation research? Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2006;29:334–347. doi: 10.1177/0163278706290409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278706290409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Cook TD, Gardner FEM, Gorman-Smith D, Howe GW, Sandler IN, Zafft KM. Standards of evidence for efficacy, effectiveness, and scale-up research in prevention science: Next generation. Prevention Science. 2015;16:893–926. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0555-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans Erwin W, van Houdenhoven Mark, Hulshof Peter JH. A framework for healthcare planning and control. In: Hall R, editor. Handbook of Healthcare System Scheduling. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haskins R, Margolis G. Show me the evidence: Obama’s fight for rigor and evidence in social policy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann C, Stoykova BA, Nixon J, Glanville JM, Misso K, Drummond MF. Do health-care decision makers find economic evaluations useful? The findings of focus group research in UK health authorities. Value in Health. 2002;5:71–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.52109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: The evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic Reviews. 2012;1:1–9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, McEwan . Cost-effectiveness analysis: Methods and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mason E, Shelton J. Facts over factions. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2016 Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/facts.

- Meyer M. The rise of the knowledge broker. Science Communication. 2010;32:118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Milner J. Everything you need to know about the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking. 2016 Apr 6; Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/urban-wire/everything-you-need-know-about-commission-evidence-based-policymaking.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Advancing the power of economic evidence to inform investments in children, youth, and families. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Using science as evidence in public policy. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell ME, Boat TF, Warner KE. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC HSR. 2014;14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver K, Lorenc T, Innvær S. New directions in evidence-based policy research: A critical analysis of the literature. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2014;12:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD. Strategic Planning for Public Relations. 4. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng V. The uses of research in policy and practice. Social policy report. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for Research in Child Development; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vandlandingham G, Silloway T. Bridging the gap between evidence and policymakers: A case study for the Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative. Public Administration Review. 2015;76:542–46. doi: 10.1111/puar.12603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]