Abstract

There is a substantial unmet clinical need for new strategies to protect the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) pool and regenerate hematopoiesis after radiation injury, either from cancer therapy or accidental exposure1,2. In addition to their role in promoting sexual dimorphisms, increasing evidence suggests that sex hormones regulate HSC self-renewal, differentiation, and proliferation3–5. We and others previously reported that sex steroid ablation promotes bone marrow (BM) lymphopoiesis and HSC recovery in aged and immunodepleted mice5–7. Here we show that a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-antagonist (LHRH-Ant), currently used widely in the clinic for sex steroid inhibition, promoted hematopoietic recovery and mouse survival when administered 24 h after an otherwise lethal dose of total body irradiation (L-TBI). Unexpectedly, this protective effect was independent of sex steroids, but instead relied on suppression of luteinizing hormone (LH) levels. Human and mouse long-term self-renewing HSCs (LT-HSCs) expressed high levels of the luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHCGR) and expand ex vitro when stimulated with LH. In contrast, suppression of LH after L-TBI inhibited entry of HSCs into the cell cycle, thus promoting quiescence of HSCs and protecting them from exhaustion. These findings reveal a role for LH in regulating HSC function and offer a new therapeutic approach for hematopoietic regeneration after injury.

BM toxicity is a common dose-limiting side-effect for most cancer therapies and is the primary cause of death for victims of accidental exposure. Despite intensive research to identify effective treatments for hematopoietic recovery and mitigation of radiation injury, available non-cellular approaches are still limited8. Although several cytokines and growth factors have shown radio-protective properties when administered before radiation exposure, few are effective in mitigating radiation toxicity in a post-injury setting, restricting their application to the worst-case scenario of a nuclear accident or terrorist attack9.

Inhibition of sex steroids, which can be achieved pharmacologically in a reversible fashion, is a well-described strategy for promoting lymphopoiesis in the BM and thymus6,7,10,11. Although the most common clinical method of sex steroid ablation has been through use of LHRH agonists, we have previously proposed that an LHRH antagonist represents a more rational approach to achieve immediate ablation of sex steroids for immune regeneration, for two reasons: LHRH antagonism is more rapid than agonism, and antagonism abrogates the initial surge in sex steroids caused by agonism12. Taken together with previous evidence of the impact of sex steroid inhibition on HSC function and the rapid hormonal suppression mediated by LHRH antagonism, we hypothesized that a LHRH antagonist could represent a rational non-cellular medical countermeasure for mitigating radiation injury and promoting hematopoietic regeneration when administered after hematopoietic insult.

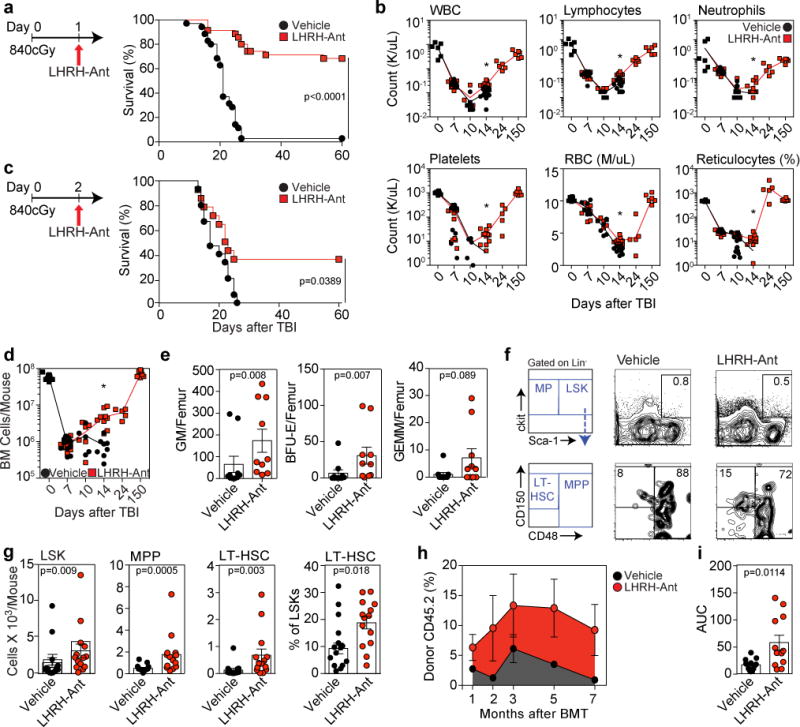

To test this hypothesis, we administered a lethal TBI (L-TBI) dose of 840 cGy to male mice, resulting in lethality in more than 90% of mice (Fig. S1a). Mice receiving the LHRH-Ant (Degarelix) 24h after L-TBI exposure showed a significant increase in survival compared to control animals treated with vehicle alone (Fig. 1a). Mouse lethality was a result of bone marrow failure, since transplantation of BM Lin−Sca1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells 3 days after L-TBI completely rescued mouse lethality (Fig. S1b). Despite similar drops in cellularity across both treatment groups for the first 10 days, complete blood counts analysis revealed that cellularity recovered only in mice treated with LHRH-Ant after L-TBI (Fig. 1b), consistent with the survival data. We next tested if LHRH-Ant could mediate even greater mouse survival when administered multiple times. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given that hormone levels are abrogated within 24 hours after administration12, treatment of mice 24 h and 15 days after L-TBI did not significantly enhance its survival benefit (Fig. S1c). Although reduced in its effectiveness, treatment with LHRH-Ant significantly enhanced mouse survival even when administered 48 h after L-TBI (Fig. 1c), further validating this treatment as a potent medical countermeasure for lethal hematopoietic radiation exposure. Notably, we also found a statistically significant benefit in survival in female mice treated with LHRH-Ant after L-TBI (Fig. S1d), although more modest in comparison to the benefit observed in male mice; this difference is potentially due to the differential effects of estrogen and testosterone on HSC function4,5.

Figure 1.

LHRH-Antagonism improves hematopoietic recovery and mouse survival after L-TBI. (a) Survival of C57BL/6 male mice injected with LHRH-Ant (n=40) or vehicle (n=40) 24h after L-TBI (840cGy) (data combined from five independent experiments). (b) Complete blood counts (CBC) of selected mice in panel “a” at day 0 (n=6), day 7 (n=7 vehicle-treated and 10 LHRH-Ant treated mice), day 10 (n=6 vehicle-treated and 6 LHRH-Ant-treated mice), day 14 (n=11 vehicle-treated and 12 LHRH-Ant-treated mice), day 24 (n=5 LHRH-Ant-treated mice), and day 150 (n=6 LHRH-Ant-treated mice). Data combined from at least two independent experiments. (c) Survival of C57BL/6 male mice treated with LHRH-Ant or vehicle 48h after L-TBI (840cGy) (n=15 mice per group). Data combined from two independent experiments. (d) BM cell counts of the mice in “a” at day 0 (n=11 mice), day 7 (n=11 mice per group), day 10 (n=5 vehicle-treated and 6 LHRH-Ant-treated mice), day 14 (n=8 vehicle-treated and 9LHRH-Ant-treated mice), day 24 (n=5 LHRH-Ant-treated mice), and day 150 (n=7 LHRH-Ant-treated mice), Data combined from at least two independent experiments. (e) CFC colonies of BM cells from vehicle or LHRHAnt treated mice (n=10 mice per group) at day 7 after L-TBI. Data combined from two independent experiments. (f) Concatenated FACS plots and representative gating strategies for the experiment in g (concatenated from three mice). (g) Total numbers of LSK, MPP, LT-HSC and the frequency of LT-HSC in vehicle and LHRH-Ant treated mice 14 days after L-TBI (n=15 vehicle-treated and 14 LHRH-Ant-treated mice). Data combined from four independent experiments. For each mouse, the tibia and femur of both legs were analyzed. (h,i) 14 days after L-TBI, BM and spleen cells from CD45.2 male mice, treated with LHRH-Ant or vehicle, were co-transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 mice with a rescue dose of 2.5×105 CD45.1 whole BM cells. (h) Total peripheral reconstitution measured as the percentage of donor CD45.2 in peripheral blood at 1 month (n=13 vehicle-treated and 12 LHRH-Ant-treated mice), 2 months (n=9 vehicle-treated and 8 LHRH-Ant-treated mice), 3 months (n=7 vehicle-treated and 8 LHRH-Ant-treated mice), 5 months (n=12 mice per group), and 7 months (n=9 vehicle-treated and 8 LHRH-Ant-treated mice). Data combined from at least two independent experiments. (i) Area under the curve for panel “h” was calculated. For panels b, d, e, g, h, and i, data is displayed as the mean ± s.e.m. Statistics for panel a and c were generated using the Mantel– Cox (log-rank) test; panels b, d, e, g, and i were computed using the unpaired nonparametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. In panels b and d *p < 0.05, comparing vehicle and LHRH-Ant treated mice

Consistent with the peripheral blood recovery of mice treated with LHRH-Ant (Figure 1b), the BM cellularity of mice treated with this compound was significantly different from that of the control group starting at day 14 after L-TBI (Fig. 1d). Next, to determine the effects of LHRH-Ant on the recovery of committed hematopoietic progenitor cells, we quantified BM colony-forming unit (CFU) activity. Whereas there was no difference in total BM cellularity at day 7 between LHRH-Ant and vehicle-treated L-TBI mice, BM-derived CFU-GM and BFU-E colony numbers were significantly increased in mice treated with LHRH-Ant (Fig. 1e). On day 14 after L-TBI, there was also an increased number of LSKs and of their downstream progenitors in LHRH-Ant treated mice, as well as significantly more LT-HSCs, which are crucial for sustained hematopoiesis (Fig. 1f,g). Given that the HSC phenotype is known to be altered by radiation13, we also adapted the standard competitive repopulation assay to evaluate the presence and relative quantity of functional HSCs after L-TBI. Taking into account the potential for mobilization of HSCs following radiation exposure14, we collected all cells from the BM and spleen of vehicle or LHRH-Ant treated mice at day 14 after L-TBI and transplanted them into irradiated hosts (along with a rescue dose of congenic WBM cells to ensure recipient mouse survival). This approach allows us to establish the effects of LHRH-Ant treatment on the total number of functional residual HSCs. Mice receiving cells from LHRH-Ant-treated L-TBI mice had significantly better hematopoietic reconstitution than mice receiving cells from vehicle-treated control L-TBI mice (Fig. 1h,i, S2) suggesting that greater numbers of functional HSCs persist in mice treated with LHRH-Ant. Analysis of the multilineage contribution of donor cells revealed that the increase in hematopoietic reconstitution was driven mostly by cells of lymphoid, and more particularly, B cell lineage (Fig. S2c), Taken together, these data suggest that pharmacological inhibition of the LHRH-receptor mitigates TBI-induced mortality and myelosuppression through protection and recovery of the HSC compartment.

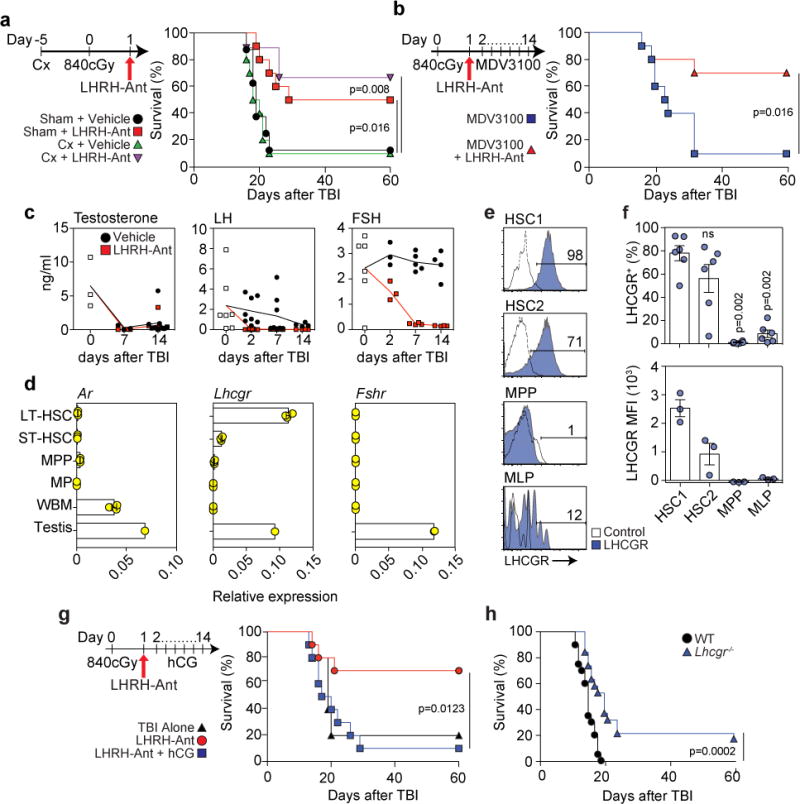

Given the previous reports linking sex steroids to HSC function5,7, our initial hypothesis was that LHRH-Ant facilitates hematopoietic recovery after radiation exposure through androgen ablation. To test this hypothesis and gain insight into the mechanisms driving the regenerative effects of LHRH-Ant, we performed surgical castration in male mice and followed their survival after L-TBI. Surprisingly, surgical castration did not protect mice from radiation injury, but simultaneous treatment of castrated mice with LHRH-Ant promoted mouse survival (Fig. 2a). However, as surgery needed to be performed 5 days prior to TBI to ensure recovery by the time of irradiation, we could not discount that the functional impacts of sex steroid ablation on HSCs when given before radiation may confound our findings4,5. To account for this possibility, we treated mice with the androgen receptor (AR) inhibitor enzalutamide (MDV3100) 24h after L-TBI. Consistent with the data in surgically castrated mice, MDV3100 treatment alone did not result in a survival benefit, but combined treatment with MDV3100 and LHRH-Ant increased mouse survival (Fig. 2b). Moreover, in line with the well-characterized toxic effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy on gonads and fertility15, TBI alone drastically reduced the levels of testosterone in mice receiving either LHRH-Ant or vehicle control, with no significant difference between these two groups (Fig. 2c). These data strongly suggest that the beneficial effects of LHRH-Ant on hematopoiesis and survival post irradiation are sex steroid-independent.

Figure 2.

The regenerative benefit of LHRH-Ant after L-TBI is dependent on suppression of LH not sex steroids. (a) Survival of sham-castrated (sham) and castrated (Cx) mice, treated with LHRH-Ant or vehicle 24 hours after TBI, (n=8 sham-treated; n=10 sham + LHRH-Ant-treated; n=10 castrated; and n=10 castrated + LHRH-Ant-treated mice). Data combined from two of three independent experiments with similar results. (b) Survival of mice receiving daily vehicle or MDV3100 treatment and treated with the LHRH-Ant or vehicle (n=10 mice per group). Data combined from two independent experiments. (c) ELISA of serum levels of LH, FSH and testosterone at timepoints after TBI (Testosterone: day 0, n=3. Vehicle groups: day7, n=3; day14, n=9. LHRH-Ant groups: day 7, n=4; day 14, n=9. LH: untreated group n=7. Vehicle groups: day 2, n=8; day 7, n=8; day 14, n=4. LHRH-Ant groups: day 2, n=8; day 7, n=7; day 14, n=4. FSH: untreated group, n=6. Vehicle groups: day 2, n=3; day 7, n=5; day 14, n=4. LHRHAnt groups: day 2, n=3; day 7, n=4; day 14, n=4 mice). Data combined from at least two independent experiments. (d) Expression of Ar, Lhcgr and Fshr was assessed by qPCR in sorted LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, MPPs, MPs and whole BM (WBM) from untreated C57BL/6 male mice (n=3 biological replicates; where each replicate was pooled from 2 mice). Data represent one out of two independent experiments with similar findings in both. The gating strategy for each population is shown in Fig. S3a. Expression in one whole testis was assessed as a positive control. Data are plotted as relative quantification normalized to the level of HPRT and beta-actin. (e-f) Expression of LHCGR on HSC1 (Lin-CD34+CD38-CD45RA-CD90+CD49f+), HSC2 (Lin-CD34+CD38-CD45RA-CD90-CD49f+), MPP (Lin-CD34+CD38-CD45RA-CD90- CD49f-) and MLP (Lin-CD34+CD38-CD45RA+CD90-CD10+) cell populations in human UCB. (e) FACS plots showing LHCGR expression for each indicated population. The gating strategy is shown in Fig. S3d and plots are representative of three independent experiments. (f) Top panel, proportion of LHCGR+ cells in human hematopoietic progenitors. Data are combined from three independent experiments using a total of 6 individual UCB units (“ns” = non-statistically significant). Bottom panel, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of LHCGR in human UCB samples. Data represent one of three independent experiments with similar findings in each. (g) Survival of mice receiving vehicle (TBI alone) (n=5), LHRH-Ant (n=10) or LHRH-Ant plus daily administration of hCG (n=10 mice). Data combined from two independent experiments. (h) Survival of WT (n=20) or Lhcgr−/− (n=19) mice exposed to 840cGy radiation dose. Data is combined from three independent experiments. For panels d and f data is displayed as the mean ± s.e.m. Statistics for panels a, b, g and h were generated using the Mantel–Cox (log-rank) test; statistics for panel f was computed using the unpaired nonparametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test.

As LHRH exerts its effects in the pituitary, we next examined effects of LHRH-Ant treatment on luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), through which LHRH affects sex steroids. In contrast to testosterone, the levels of which were abrogated after TBI, the levels of LH decreased gradually and the levels of FSH were not affected (Fig. 2c). As expected, the levels of LH and FSH were dramatically decreased in irradiated mice also given LHRH-Ant treatment (Fig. 2c). Given these effects on hormone levels after TBI, we analyzed mRNA expression of AR as well as the LH and FSH receptors in purified populations of HSPCs. We found almost no detectable expression of androgen receptor (Ar) or follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (Fshr) in any of the HSPC subsets examined, including primitive HSCs (Fig. 2d). In contrast, expression of luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor (Lhcgr) was highly enriched in long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs), and at comparable levels to those observed in the testes (Fig. 2d). Notably, we observed a similar Lhcgr expression pattern in HSPCs of female mice (Fig. S3b). Further analysis revealed that Lhcgr expression was specific to LT-HSCs, with little or no expression found in purified BM cells that comprise the hematopoietic niche (Fig. S3c). These findings are consistent with publically accessible gene expression databases. Using recently identified surface markers enabling granular characterization of the human HSC compartment (Fig. S3d)16, we found that LHCGR expression was significantly enriched on the most primitive HSPC subsets, HSC1 (Lin−CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90+CD49f+) and HSC2 (CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90−CD49f+); expression was nearly absent on downstream MPPs (multi-potent progenitors) and MLPs (multi-lymphoid progenitors) (Fig. 2e,f). Although Lhcgr expression has previously been demonstrated in a crude fraction of Lin−CD45+Sca1+ cells3, this is the first evidence to our knowledge of its enriched expression in the most primitive HSCs.

Given the restriction of Lhcgr expression to primitive HSCs, we sought to definitively determine whether the regenerative effects of LHRH-Ant treatment depend specifically on LH suppression, by testing whether stimulation of Lhcgr would abrogate the beneficial effects of LHRH-Ant treatment. For these studies we employed the alternative Lhcgr ligand human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), due to its longer half-life compared to LH and widespread use to stimulate LHCGR in mice17. Consistent with our hypothesis, administration of hCG abrogated the beneficial effects of LHRH-Ant on survival after radiation injury (Fig. 2g). Given the negative impact of LH signaling during hematopoietic recovery after radiation, we hypothesized that mice deficient for Lhcgr would be protected from irradiation. We found that Lhcgr-KO mice had a small but statistically significant increase in survival when exposed to L-TBI, as compared to littermate control mice (Fig 2h). Consistent with the only modest increase in survival observed in Lhcgr-KO mice, analysis of hematopoietic recovery 14 days after L-TBI revealed only trends toward increased numbers of LT-HSCs and peripheral blood counts in Lhcgr-KO mice (Fig. S4a,b). However, in a less extreme model of hematopoietic injury using a sub-lethal dose of TBI (SL-TBI, 550cGy), we could demonstrate a significant increase in the number of LT-HSCs in Lhcgr-KO mice (Fig. S4c).

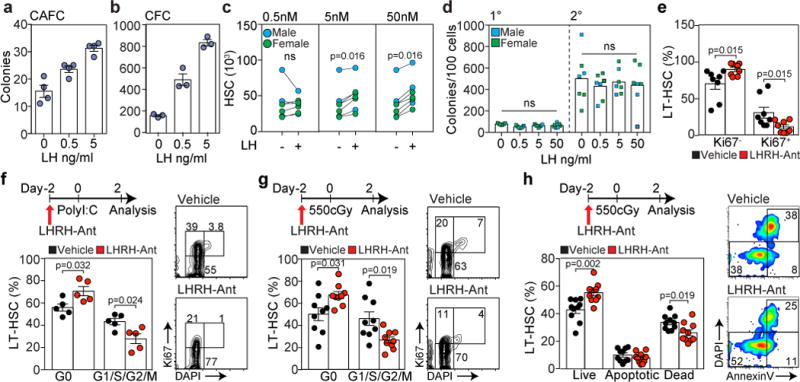

The control of HSC self-renewal, differentiation, and proliferation is a tightly regulated process crucial for maintaining the HSC pool18–22. Maintenance of the HSC pool is particularly relevant in the context of hematopoietic injury, such as high dose or repeated rounds of chemotherapy or irradiation, when dormant HSCs transiently proliferate to replenish blood cells and unbalanced HSC proliferation can lead to stem cell exhaustion and long-term myelosuppression23–25. Consistent with its previously described role in promoting the proliferation of cells, including gonadal and neuronal cells26,27, LH significantly enhanced colony formation of LSK cells in cobblestone area-forming cell (CAFC) and colony-forming cell (CFC) assays (Fig. 3a,b). Notably, LH was also able to significantly expand human umbilical cord blood (UCB) HSCs (CD34+CD133+CD45RA-CD90+) in vitro in a stroma-free culture system (Fig. 3c and Fig. S5a); these expanded HSCs maintained robust primary and secondary colony-forming potential (Fig. 3d). Although there is a clear need for HSC proliferation to ensure regenerative hematopoiesis28, previous reports have also shown that induction of HSC quiescence after high-dose irradiation correlates with increased hematopoietic recovery and enhanced mouse survival23,25,29,30. Consistent with this notion, when we analyzed the cell cycle status of HSCs in LHRH-Ant treated mice after L-TBI, we found a significantly higher proportion of Ki-67− quiescent LT-HSCs (CD150+CD48−LSK) in the BM of the LHRH-Ant-treated group as compared to the vehicle group (Fig. 3e and Fig. S5b). Despite the decreased proportion of proliferating HSCs, there was no effect of LHRH-Ant treatment on the absolute number of Ki-67+ HSCs (data not shown). This result, taken, together with the lack of an effect of LHRH-Ant treatment on MPP proliferation (Fig. S5c), suggests that proliferating HSCs contribute to the effects of LHRH-Ant treatment after TBI on early hematopoiesis, notably increases in MPP number and HSPC function (Fig. 1e–g). Mechanistically, inhibition of LH signaling retains HSCs in a quiescent phase and protects them from LH-induced entry into the cell cycle after high-dose irradiation.

Figure 3.

LH directly promotes HSC expansion and its suppression after hematopoietic insults decreases HSC entry into cell cycle. (a) LSK cells (2×103) from a central pool were co-cultured in quadruplicate with MS-5 cells at the indicated concentrations of LH. Total number of CAFC were assessed after 3 weeks. Data represents one out of two independent experiments with similar results. (b) Total number of CFCs generated from LSK cells (3×103) cultured at the indicated LH concentrations. Data represents one out of two independent experiments performed in triplicate with similar results. (c) CD34+ enriched human UCB cells were cultured in serum and stroma-free cultured conditions in the absence or presence of LH at the indicated concentrations for 7 days, at which time point the number of HSC1 cells (CD34+CD133+CD45RA-CD90+) were quantified by FACS (n=7 individual UCB units plated in triplicate). (d) Primary and secondary hematopoietic colonies generated from HSC1-enriched cells previously cultured with LH as in c (n=7 individual UCB units). (e) Frequency of Ki67+ and Ki67- LT-HSCs in BM of vehicle and LHRH-Ant treated mice 14 days after L-TBI (n=8 mice per group). Data is combined from two independent experiments. (f) Cell cycle analysis of LT-HSCs in vehicle and LHRH-Ant treated mice after poly I:C treatment (n=6 mice per group). Data is combined from two independent experiments. (g) Cell cycle analysis of LT-HSCs in vehicle and LHRH-Ant treated mice after SL-TBI (n=9 mice per group). Data is combined from three independent experiments. (h) Annexin V and DAPI analysis of LT-HSCs using the experimental scheme shown in f (n=10 mice per group). Data is combined from two independent experiments. Concatenated FACS plots of five individual mice are shown on the right. For panels a, b, d, e, f, g and h data is displayed as the mean ± s.e.m. Statistics for panels a, b, d, e, f, g and h were generated using unpaired nonparametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test; statistics for panel c were calculated using the non-parametric paired Wilcoxon rank sum test; and statistics for panel d were calculated using the non-parametric paired Friedman test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test.

To further test this hypothesis, we used two additional models to induce HSCs out of quiescence: poly I:C and SL-TBI. To eliminate any potential effects of downstream sex steroids on HSCs, all mice in these studies were surgically castrated prior to any study-associated treatment. Consistent with our hypothesis, ablation of LH production using LHRH-Ant resulted in a significantly higher number of LT-HSCs in G0 in both models (Fig. 3f,g and Fig. S6). To evaluate if promotion of HSC quiescence results in increased cell viability after radiation exposure, we analyzed cell apoptosis using AnnexinV/DAPI staining. Using the same administration scheme as described in Figure 3g, we found that LHRH-Ant treatment led to a significant increase in the proportion of live LT-HSCs as compared to vehicle treated mice (Fig. 3h).

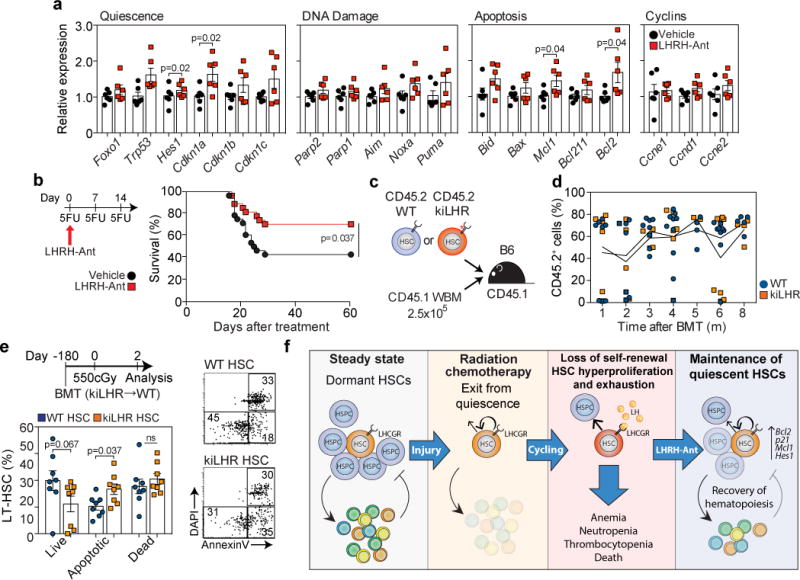

To gain insight into the molecular effects of LHRH-Ant treatment in HSCs, we purified LT-HSCs from mice after SL-TBI (300cGy) with or without LHRH-Ant treatment and assessed the expression of key genes associated with quiescence, proliferation, DNA damage response and apoptosis of HSCs. Broadly, we observed that LT-HSCs derived from LHRH-Ant-treated mice showed significant overexpression of genes related to quiescence and apoptosis (p=0.02 and p=0.004, respectively), as compared to LT-HSCs from vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 4a). Within these categories, we found significantly higher levels of Hes1 and Cdkn1a (p21), two genes previously identified to be critical in promoting HSC quiescence22,31, as well as significantly higher levels of the anti-apoptotic genes Bcl2 and Mcl1. Notably, Bcl2 and Mcl1 have been implicated in regulating HSC quiescence and survival, respectively32,33.

Figure 4.

LH suppression promotes quiescence and protects HSCs from exhaustion. (a) Expression of the indicated genes, as assessed by qPCR, in LT-HSCs that were sort-purified two days after 300 cGy radiation in surgically-castrated mice treated with vehicle or LHRH-Ant two days prior to radiation. The data are expressed as fold increase relative to the vehicle control group and were normalized to the average of three housekeeping genes (Gapdh, beta-actin, Sdha) (n=6 biological replicates per group, with each replicate comprised of 3 mice). Data is combined from two independent experiments. (b) Survival of vehicle (n=28) and LHRH-Ant (n=27) treated mice following sequential 5-FU treatment. Data is combined from three independent experiments. (c) Schematic representation of the experiment for which the data are shown in d. 500 LT-HSCs from WT or KiLHRD582G mice were sort-purified and transplanted into CD45.1 irradiated hosts together with a rescue dose of 2.5×105 CD45.1 whole BM cells. (d) Total peripheral reconstitution was measured as the percentage of donor CD45.2 in peripheral blood over 8 months (WT: 1 month, n=8; 2 months, n=7; 3 months, n=8; 4 months, n=10; 5 months, n=4; 6 months, n=9; 8 months, n=5; KiLHRD582G mice: 1 month, n=6; 2 months, n=7; 3 months, n=5; 4 months, n=6; 5 months, n=3; 6 months, n=8; 8 months, n=4 mice). Data are combined from at least two independent experiments. (e) The mice in d were exposed to 550cGy and LT-HSCs subjected to Annexin V and DAPI analysis by FACS two days later (n=8 mice per group). Data is combined from two independent experiments. (f) Schematic model of the proposed mechanism by which LHRH-Ant promotes HSC recovery after hematopoietic insult. For panels a, d, and e data is displayed as the mean ± s.e.m. Statistics for panels a and e were generated using the unpaired nonparametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test; panel b was calculated using the Mantel–Cox (log-rank) test.

To test whether the effects of LHRH-Ant on HSC quiescence and survival after hematopoietic stress could confer protection against chemotherapy-induced myeloablation, we challenged mice with successive doses of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Serial 5-FU treatment is a well-established method to functionally test HSC proliferation and self-renewal by ablating proliferating HSCs and ultimately leads to BM failure and death of the treated mice18,22. Abrogation of LH production significantly improved survival after serial 5-FU challenge (Fig. 4b), supporting the concept that LHRH-Ant treatment promotes HSC quiescence and survival.

To evaluate the cell intrinsic effects of LHCGR stimulation in HSCs, we created hematopoietic chimeras using as donor cells LT-HSCs from WT or KiLHRD582G mice; KiLHRD582G mice carry a gain of function mutation (D582G) in Lhcgr that confers constitutive activity to the LHCGR27 (Fig. 4c). Peripheral blood analysis of donor cell reconstitution did not reveal differences between the two types of donor cells over the time course analyzed, suggesting that constitutive LHCGR signaling does not have substantial effects on HSC repopulating potential and survival (Fig. 4d). We hypothesized that stimulation of the LHCGR could be detrimental to HSCs that proliferate after having been subjected to hematopoietic injury. To test this hypothesis, we exposed chimeric mice 6 months after transplantation to SL-TBI and evaluated cell HSC apoptosis two days later. Consistent with our previous findings, constitutive LHCGR signaling in KiLHRD582G HSCs resulted in a significant reduction in LT-HSC survival after radiation exposure, as measured by a significantly higher proportion of apoptotic cells as compared to LT-HSC WT cells (Fig. 4e).

Taken together, our data demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of LH signaling, as achieved in mice using a single dose of an LHRH antagonist, represents a rational and feasible approach to preserve the HSC pool after high dose radiation, thereby mitigating acute hematopoietic radiation syndrome. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, this effect was not mediated by sex steroids, but rather was due to inhibition of LH signaling in the most primitive HSCs. Although it is clear that HSC proliferation is critical for regeneration after injury, there is a growing consensus that treatments that promote HSC quiescence immediately after damage can aid in mitigating HSC exhaustion and ultimately promote hematopoietic recovery22,23,25,30,34–36. We found that LHRH-Ant treatment restrained entry of HSC into the cell cycle after hematopoietic insult and promoted the expression of genes associated with HSC quiescence, including Hes1 and Cdkn1a (p21)22,31. Particularly notable was the increased expression of p21; this protein is redundant in HSCs in steady state conditions but plays a crucial pro-survival role in the event of hematopoietic stress22,37,38. We also observed increased expression of the anti-apoptotic genes Bcl2 and Mcl1, which have been implicated in regulating HSC quiescence and survival, respectively32,33. The ability of LHRH-Ant treatment to rescue mice after they have received a hematopoietic lethal dose of TBI indicates that some HSCs must survive the initial hit of radiation. We propose that these remaining HSCs must proliferate in order to regenerate hematopoiesis, but a combination of cell exhaustion and intracellular damage leads to their apoptosis and ultimately to BM failure and death of the mice. By inducing quiescence and/or by inhibiting apoptosis, LHRH-Ant prevents HSC exhaustion, thereby promoting long-term persistent hematopoiesis (Fig. 4f).

In addition to these direct effects of LH on HSCs, there also remains the possibility that other effects of LHRH-Ant could contribute towards hematopoietic recovery. In particular, there are likely to be widespread effects due to systemic hormonal ablation following LHRH-Ant treatment. We have previously shown that androgen suppression using surgical castration can result in substantial beneficial effects on the BM environment and on HSC function7, and several other groups have recently reported the regulation of HSC self-renewal and proliferation by estrogen4,5. Hematopoietic radiation injury leads to HSC senescence, manifested by myeloid skewing of HSCs and marked reduction in their long-term repopulation capacity21,39, both of which are also hallmark traits of aging HSCs40. Notably, androgen ablation (via surgical castration) can directly promote T and B lymphopoiesis in male mice and can reverse age-related declines in HSC function11. Thus it is possible that the combinatory events of enhanced HSC quiescence (mediated by LH suppression) and enhanced hematopoietic support from the BM niche (mediated by androgen suppression) cooperate in promoting HSC recovery and survival of mice after L-TBI. Importantly, these secondary effects of androgen and estrogen ablation could also explain the differential effects of LHRH-Ant treatment on the survival of male and female mice.

Taken together, these findings offer not only a rational and safe medical countermeasure to hematopoietic radiation injury using a drug already FDA approved for other indications, but also demonstrate a heretofore unrecognized role for LH signaling in the regulation of HSC homeostasis.

Methods

Mice

Inbred male or female C57BL/6 (CD45.2) or B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ (CD45.1) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, USA) and used at 7 to 12 week old. Lhcgr-KO mice were obtained from Zhenmin Lei (University of Louisville School of Medicine). KiLHRD582G mice27 were obtained from Prema Narayan (Southern Illinois University School of Medicine). Total body irradiation was performed with a Gammacell 40 Irradiator (Cs-137), with an approximate average dose rate of 95 cGy/min, in a plexiglass mouse pie cage with mice in individual chambers. To assess mouse survival after radiation, mice were monitored for up to 60 days after TBI. Mouse cages were randomly allocated to each group prior the start of the experiment and all studies were approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center or Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Cell isolation and cord blood processing

BM cells were flushed from intact femurs and tibia, and spleens were mashed with glass slides to generate single-cell suspensions. Unless otherwise stated, all cell numbers in this study were standardized as total counts per two legs or per spleen. Endosteal cells (for isolation of OBLs) were isolated by crushing flushed bones and digesting with 0.15% (w/v) Collagenase (Roche, Germany) and 0.1% (w/v) DNAse I (Roche, Germany) in RPMI-1640. Human cord blood was obtained from the New York Blood Center (New York, NY) and Swedish Medical Center (Seattle, WA). Mothers signed an informed consent to allow collection of cord blood. Cord blood samples were layered on a Ficoll/Paque gradient and processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. CD34+ cells were then enriched by magnetic separation using the human CD34 MicroBead kit (Miltenyi Biotec).

Reagents

Degarelix acetate (Firmagon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals), an LHRH antagonist, was administered in a single dose sc to mice at a dose of 40mg/kg. To induce HSC out of quiescence, mice were given either TBI or Poly I:C (InvivoGen) ip at a dose of 5mg/kg, as previously described23,41,42. For in vivo mouse studies, hCG (Cellsciences, cat no. CRC101 and Sigma, cat no. CG10) was administered sc to mice at a dose of 20IU; MDV3100 (Selleckchem) was resuspended in a mixture of 45% PBS, 45% PEG and 10% DMSO and administered daily to mice by oral gavage at a dose of 10mg/kg.; and 5-FU (InvivoGen) was administered ip at a dose of 150 mg/kg once every 7 days for 3 weeks as previously described22,34,43. LH from human pituitary (Sigma, cat no. L6420) was used at the indicated concentrations for in vitro studies. The antibodies used in this study for flow cytometry and sorting are described in Table S1. Flow Cytometry was performed on an LSR II or ARIA II (BD Biosciences) using FACSDiva Software (BD Biosceinces). For intracellular Ki67 and DAPI staining, cells were stained with surface markers, fixed, and permeabilized using the Fixation/Permeabilization kit (eBioscience) according to the manufacturers instructions. For AnnexinV/DAPI staining, cells were surface labeled, washed and incubated with Annexin V antibody (BD Pharmingen) in Annexin V Binding Buffer (BD Pharmingen).

CFC and CAFC Assays

Colony assays were performed as previously described with minor modifications44. Murine cells: For CFC assays in Figure 1e, BM nucleated cells (BMNCs) were suspended in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 1.2% methylcellulose (Dow Chemicals, MI), 30% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 0.1 mM monothiolglycerol, 0.1 mg/ml hemin (Sigma Inc, MO), 0.05 mg gentamicin, 20 ng/mL murine c-kit ligand (Amgen Inc, CA), 6 units/ml human Epogen (Amgen Inc. CA), and 20 ng/mL murine IL-3 (Pepro Tech Inc., NJ) and plated at a concentration of 5×104 cell/mL and colonies were scored after 10 days. When fewer BMNCs were available, equal amounts of all of the BM cells available were plated. For CFC assays in Figure 3b, 3×103 purified LSK (Lineage−Sca1+ckit+) were cultured in StemSpan (Stemcell Technologies) supplemented with SCF, TPO and FLT3L (all by Peprotech 2 ng/ml each). Fresh LH was added every day for the first 3 days of in vitro culture. After 7 days of culture, the cells were harvested and subjected to the CFC bioassay. For CAFC assays, 2×103 purified LSK cells were co-cultured with confluent MS-5 cells (kindly provided by Dr. KJ Mori (Niigata University, Niigata, Japan)45 in α-MEM containing 12.5% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, GA), 12.5% horse serum (GE Health Life Science, Utah), 1 μM Hydrocortisone (Sigma Inc, MO) and 5×10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Fisher Scientific). Half of the culture medium was replenished weekly and after 3 weeks of co-culture, CAFCs were scored as phase-dark hematopoietic clones of at least 5 cells beneath the stromal layer, as observed using an inverted microscope. Human cells: Human umbilical cord blood (UCB) CD34+ cells were enriched and cultured as previously described46 using anti-CD34 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). Enriched and sort-purified CD34+ cells were cultured in StemSpan (Stemcell Technologies) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin streptomycin (Gibco by Life Technologies) and SCF, TPO and FLT3L (all by Peprotech 100 ng/ml each) with 50% exchange of culture medium on day 4. Fresh LH was added every day for the total duration of in vitro culture. For primary CFC assays, 400 sorted cells were seeded into 1 ml MethoCult H4435 (StemCell Technologies). Hematopoietic colonies were microscopically analyzed by morphology, shape and color (hemoglobinized) after 12–14 days. For secondary CFC assays, cells were harvested, dissociated, washed, seeded into 3.5 ml Methocult H4434, and colonies that arose were analyzed and quantified after 12–14 days without discrimination of colony subtypes.

Bone marrow transplantation

In the transplantation experiment described in Figure 1h, cells were collected from the BM (femurs and tibias from both legs) and spleen from CD45.2+ vehicle or LHRH-Ant treated mice at day 14 after L-TBI. Cells were then enriched for HSCs by depletion of lineage+ cells and then transplanted into irradiated (1100 cGy TBI, split dose) CD45.1+ hosts at a ratio of one donor to one recipient along with 2.5×105 CD45.1+ rescue whole BM cells, through tail vein injection. Donor chimerism was monitored monthly after transplant. In the LSK transplant in Figure S1b, LSK cells from BM were FACS purified. In the experiments using KiLHRD582G donor cells in Figure 4c-e, LT-HSCs (LSK CD48-CD150+) from WT or KiLHRD582G mice were FACS purified. 500 WT or KiLHRD582G LT-HSCs (LSK CD48-CD150+) were transplanted along with 2.5×105 CD45.1+ competitor whole BM cells into lethally irradiated hosts.

Real time PCR

Reverse transcription-PCR was performed using the QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (QIAGEN). For real-time PCR, specific primer and probe sets were obtained from Applied Biosystems as follows: β−actin (Mm01205647_g1); HPRT (Mm00446968_m1); AR (Mm00442688_m1); FSHR (Mm00442819_m1); LHCGR (Mm00442931_m1). A custom-made RT2 qPCR Primer Array (QIAGEN) was used to assess the genes listed in Figure 4a: target-specific primers were designed and validated by the manufacture. PCR was done on ABI 7500 (Applied Biosystems) or Step-One Plus (Applied Biosystems) instruments with TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Relative amounts of mRNA were calculated by the Ct method. For genes analyzed in Figure 4a, total RNA was isolated from LT-HSCs (lineage−Sca-1+c-Kit+CD48-CD150+CD34-CD135-) sorted directly into RLT buffer using the RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was generated using SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermofisher). Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix (Thermofisher) was used to amplify the PCR targets of the custom-made RT2 qPCR Primer Array (QIAGEN). Array plates were run on an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 7 Flex thermo cycler and analyzed using the delta-CT method.

Statistics

Sample sizes were based on previously published work and preliminary studies; the effect size for each study was estimated, and required sample sizes were calculated using G*Power (v3.1.9.2)47 for an a=0.05 and b=0.8. For each experiment, replicates are noted in the figure legends. Where indicated in the figure legends, bars and error bars represent the mean + SEM for the various. Briefly: for in vivo studies, statistics were performed on biologically independent replicates combined from at least two individual experiments (unless otherwise stated); for in vitro studies, biologically independent samples were plated in either triplicate or quadruplicate (as a technical replicate) but statistics were performed only on biologically independent samples. No samples or animals were excluded from the analysis except for mouse peripheral blood analysis where outliers were detected prior to analysis with two-sided Grubbs’ test. Investigators were not blinded to experimental conditions, but for all lethal TBI studies staff monitoring mice for survival were blinded to experimental treatment. For all statistical analysis, no assumption of normality was made so non-parametric tests were used. Analysis of differences between two groups was made using the Mann-Whitney U test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate; and for analysis of survival curves, statistics were generated using the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. Differential analyses of functional gene groups (Quiescence, DNA Damage, Apoptosis, Cyclins) in Fig. 4a were computed using Fisher’s method. All tests performed were two sided, except for gene functional group analysis. All statistics were calculated and display graphs generated using GraphPad 6.

Editorial summary

A luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone antagonist, used clinically for sex steroid inhibition, promotes hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and thereby promotes hematopoietic recovery and survival of lethally-irradiated mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of M. Calafiore, H. Jay, J. Gupta and E. Levy; A. Gomes for assistance with the statistical analysis; and the MSKCC Research Animal Resource Center for excellent animal care. We also gratefully acknowledge C. Delaney for providing UCB units. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health award numbers R00-CA176376 (Dudakov), R01-HL069929 (M.R.M. van den Brink), R01-AI080455 (M.R.M. van den Brink), R01-AI101406 (M.R.M. van den Brink), P30 CA008748 (Thompson), P01-CA023766 (R. J. O’Reilly), Project 4 of P01-CA023766 (M.R.M. van den Brink), and 1R01HL123340–01A1 (Cadwell). Support was also received from The Lymphoma Foundation, The Susan and Peter Solomon Divisional Genomics Program, and MSKCC Cycle for Survival. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement No [602587]. E.V. was supported by fellowships from the Italian Foundation for Cancer Research, the Italian Society of Pharmacology, and an American Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation new investigator award. J.A.D. was also supported by a C.J. Martin fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, a Scholar Award from the American Society of Hematology, and the Mechtild Harf Research Grant from the DKMS Foundation for Giving Life. J.J.T. was also supported by Dorris J. Hutchison Student Fellowship from Sloan Kettering Institute. T.W. was supported by a Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds MD fellowship.

Footnotes

Author contributions: E.V. contributed to the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of the studies and drafting of the manuscript; J.J. T. contributed to the execution and interpretation of the studies and drafting of the manuscript; S.R. performed studies on human UCBs under the guidance of H.-P.K.; K.C. performed studies on LHCGR expression; S.J.-H. performed studies on murine CAFCs and CFCs under the guidance of M.A.M.; K.V.A., L.F.Y., A.L., O.M.S., S.L., F.K. performed, analyzed and helped interpreting experiments; Y.S., T.W., R.R.J., A.M.H. helped interpreting experiments; P.N. and Z.L. provided KiLHRD582G and Lhcgr-KO mice respectively. M.R.M.vdB and J.A.D. designed, interpreted and supervised all studies and wrote the manuscript. A provisional patent application has been filed on the use of LHRH-Ant as a treatment for hematopoietic recovery from radiation injury (US 15/033,178) with E.V., J.A.D. and M.R.M.v.d.B. listed as inventors. A provisional patent application has been filed on the use of LH to create, ablate and modify primitive stem cell populations (US 62/566,897) E.V., J.A.D., S.R., H.-P.K., and M.R.M.v.d.B. listed as inventors.

Data availability: Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Dainiak N. Hematologic consequences of exposure to ionizing radiation. Experimental hematology. 2002;30:513–528. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anno GH, Young RW, Bloom RM, Mercier JR. Dose response relationships for acute ionizing-radiation lethality. Health Phys. 2003;84:565–575. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mierzejewska K, et al. Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells Express Several Functional Sex Hormone Receptors-Novel Evidence for a Potential Developmental Link Between Hematopoiesis and Primordial Germ Cells. Stem cells and development. 2015 doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez-Aguilera A, et al. Estrogen signaling selectively induces apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors and myeloid neoplasms without harming steady-state hematopoiesis. Cell stem cell. 2014;15:791–804. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakada D, et al. Oestrogen increases haematopoietic stem-cell self-renewal in females and during pregnancy. Nature. 2014;505:555–558. doi: 10.1038/nature12932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dudakov JA, et al. Sex Steroid Ablation Enhances Hematopoietic Recovery following Cytotoxic Antineoplastic Therapy in Aged Mice. Journal of Immunology. 2009;183:7084–7094. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khong DM, et al. Enhanced Hematopoietic Stem Cell Function Mediates Immune Regeneration following Sex Steroid Blockade. Stem cell reports. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams JP, et al. Animal models for medical countermeasures to radiation exposure. Radiat Res. 2010;173:557–578. doi: 10.1667/RR1880.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koukourakis MI. Radiation damage and radioprotectants: new concepts in the era of molecular medicine. The British journal of radiology. 2012;85:313–330. doi: 10.1259/bjr/16386034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg GL, et al. Sex Steroid Ablation Enhances Immune Reconstitution Following Cytotoxic Antineoplastic Therapy in Young Mice. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184:6014–6024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudakov JA, Goldberg GL, Reiseger JJ, Chidgey AP, Boyd RL. Withdrawal of Sex Steroids Reverses Age- and Chemotherapy-Related Defects in Bone Marrow Lymphopoiesis. J Immunol. 2009;182:6247–6260. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Velardi E, et al. Sex steroid blockade enhances thymopoiesis by modulating Notch signaling. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1084/jem.20131289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katayama N, et al. Stage-specific expression of c-kit protein by murine hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1993;82:2353–2360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, Wang G, Cui J, Xue L, Cai L. Low-dose radiation (LDR) induces hematopoietic hormesis: LDR-induced mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells into peripheral blood circulation. Experimental hematology. 2004;32:1088–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meistrich ML. Male gonadal toxicity. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2009;53:261–266. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Notta F, et al. Isolation of single human hematopoietic stem cells capable of long-term multilineage engraftment. Science. 2011;333:218–221. doi: 10.1126/science.1201219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi J, Smitz J. Luteinizing hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin: origins of difference. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;383:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai JJ, et al. Nrf2 regulates haematopoietic stem cell function. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:309–316. doi: 10.1038/ncb2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kharas MG, et al. Constitutively active AKT depletes hematopoietic stem cells and induces leukemia in mice. Blood. 2010;115:1406–1415. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-229443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang YV, et al. Fine-tuning p53 activity through C-terminal modification significantly contributes to HSC homeostasis and mouse radiosensitivity. Genes & development. 2011;25:1426–1438. doi: 10.1101/gad.2024411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Schulte BA, LaRue AC, Ogawa M, Zhou D. Total body irradiation selectively induces murine hematopoietic stem cell senescence. Blood. 2006;107:358–366. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng T, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science. 2000;287:1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson SM, et al. Mitigation of hematologic radiation toxicity in mice through pharmacological quiescence induced by CDK4/6 inhibition. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:2528–2536. doi: 10.1172/JCI41402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C, et al. TSC-mTOR maintains quiescence and function of hematopoietic stem cells by repressing mitochondrial biogenesis and reactive oxygen species. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:2397–2408. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Himburg HA, et al. Pleiotrophin mediates hematopoietic regeneration via activation of RAS. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:4753–4758. doi: 10.1172/JCI76838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shiraishi K, Ascoli M. Lutropin/choriogonadotropin stimulate the proliferation of primary cultures of rat Leydig cells through a pathway that involves activation of the extracellularly regulated kinase 1/2 cascade. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3214–3225. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGee SR, Narayan P. Precocious puberty and Leydig cell hyperplasia in male mice with a gain of function mutation in the LH receptor gene. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3900–3913. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brenet F, Kermani P, Spektor R, Rafii S, Scandura JM. TGFbeta restores hematopoietic homeostasis after myelosuppressive chemotherapy. J Exp Med. 2013;210:623–639. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zsebo KM, et al. Radioprotection of mice by recombinant rat stem cell factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:9464–9468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goncalves KA, et al. Angiogenin Promotes Hematopoietic Regeneration by Dichotomously Regulating Quiescence of Stem and Progenitor Cells. Cell. 2016;166:894–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu X, et al. HES1 inhibits cycling of hematopoietic progenitor cells via DNA binding. Stem Cells. 2006;24:876–888. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Opferman JT, et al. Obligate role of anti-apoptotic MCL-1 in the survival of hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2005;307:1101–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1106114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qing Y, Wang Z, Bunting KD, Gerson SL. Bcl2 overexpression rescues the hematopoietic stem cell defects in Ku70-deficient mice by restoration of quiescence. Blood. 2014;123:1002–1011. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-521716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai JJ, et al. Nrf2 regulates haematopoietic stem cell function. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:309–316. doi: 10.1038/ncb2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He S, et al. Transient CDK4/6 inhibition protects hematopoietic stem cells from chemotherapy-induced exhaustion. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winkler IG, et al. Vascular niche E-selectin regulates hematopoietic stem cell dormancy, self renewal and chemoresistance. Nat Med. 2012;18:1651–1657. doi: 10.1038/nm.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Os R, et al. A Limited role for p21Cip1/Waf1 in maintaining normal hematopoietic stem cell functioning. Stem Cells. 2007;25:836–843. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foudi A, et al. Analysis of histone 2B-GFP retention reveals slowly cycling hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:84–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shao L, et al. Total body irradiation causes long-term mouse BM injury via induction of HSC premature senescence in an Ink4a- and Arf-independent manner. Blood. 2014;123:3105–3115. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-515619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geiger H, de Haan G, Florian MC. The ageing haematopoietic stem cell compartment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:376–389. doi: 10.1038/nri3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Essers MA, et al. IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2009;458:904–908. doi: 10.1038/nature07815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doan PL, et al. Epidermal growth factor regulates hematopoietic regeneration after radiation injury. Nature medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nm.3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Randall TD, Weissman IL. Phenotypic and functional changes induced at the clonal level in hematopoietic stem cells after 5-fluorouracil treatment. Blood. 1997;89:3596–3606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jo DY, Rafii S, Hamada T, Moore MA. Chemotaxis of primitive hematopoietic cells in response to stromal cell-derived factor-1. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2000;105:101–111. doi: 10.1172/JCI7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Itoh K, et al. Reproducible establishment of hemopoietic supportive stromal cell lines from murine bone marrow. Experimental hematology. 1989;17:145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Radtke S, Haworth KG, Kiem HP. The frequency of multipotent CD133(+)CD45RA(-)CD34(+) hematopoietic stem cells is not increased in fetal liver compared with adult stem cell sources. Experimental hematology. 2016;44:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.