The mechanisms of action of cytotoxic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) include direct effects via agonistic or antagonistic binding, and FcγR-dependent mechanisms to induce antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC). FcγR engagement has been shown to be the critical determinant of mAb therapeutic efficacy in humans1, 2. An antibody’s Fc domain’s relative affinity for the activating and inhibitory FcγR, called the A/I ratio, can determine its functional output3, and is directly correlated to therapeutic efficacy in vivo4. This has spawned recent efforts to engineer antibodies with enhanced activating FcγR affinity.

Only 14% of promising mAb therapies prove effective in patients and most do not make it to the market, despite strong preclinical efficacy in vivo5. Anti-cancer antibodies are even less successful than those for other indications. This problem calls for better predictive models that can more efficiently determine whether an antibody will succeed in the clinic.

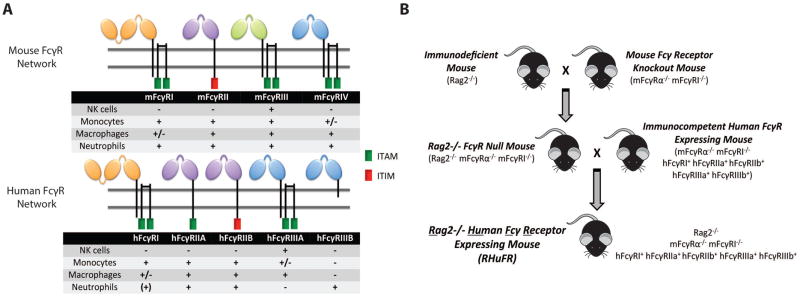

The critical differences between mouse and human FcγR networks may cause the poor predictive power of preclinical models (Figure 1A). Neutrophils from humans, but not from mice, express hFcγRIIIB. Mouse NK cells express mFcγRIII, while human NK cells express hFcγRIIIA. mFcγRIII has been shown to modestly contribute to mAb efficacy in vivo6, with mFcγRIV being the critical receptor for antibody therapy. Meanwhile, hFcγRIIIA is a key mediator of antibody therapy in humans2. Furthermore, differences in the level of cellular expression results in different thresholds for activation. Human IgG1—the human antibody subclass with the highest capacity for ADCC—has large affinity differences for mouse and human FcγRs, which may change functional output of a hIgG1 tested in a mouse versus a human. Furthermore, with the recent clinical introduction of Fc engineered antibodies, testing of an affinity-enhanced antibody in a mouse lacking its key FcγR has little value.

Figure 1. Creation of the immunodeficient human FcγR expressing RHuFR mice.

(A) Figure: Human and mouse Fcγ receptors. ITAM (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif); ITIM (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif). Table: + indicates receptor expression, - indicates lack of receptor expression, (+) indicates inducible expression, +/− indicates expression on some, but not all, cellular subsets. (B) Breeding scheme used.

Recently, immune competent mice expressing only the human FcγRs have been created7. This mouse contains each of the individual hFcγR transgenes (hFcγRI, hFcγRIIAR131, hFcγRIIBI232, hFcγRIIIAF158, and hFcγRIIIB) under the control of their endogenous promoters and regulatory elements and has proven to be a critical tool for the evaluation and study of hIgGs in models of infectious disease and syngeneic tumor therapy8. However, this model has no ability to engraft human cancers that bear human-specific epitopes that are not shared by mice, nor does transgenic expression of such human epitopes in mouse cancers truly reflect the native expression levels. Therefore, a new mouse model expressing human FcγRs in an immune deficient setting is necessary for better preclinical efficacy testing of therapeutic antibodies.

The first step to establish the new immune deficient “RHuFR” mice was to cross immunodeficient Rag2−/− mice that lack mature B and T cells to mouse FcγR knockout mice (mFcγRI−/−, mFcγRα−/−)7, creating Rag2−/− FcγR Null mice (Figure 1B). This FcγR Null strain successfully demonstrates the loss of mouse FcγR expression on all leukocyte populations (Figure S1). This strain was then crossed to the immunocompetent human FcγR+ mice7. The product of this breeding was a Rag2−/− human FcγR+ mouse (RHuFR). Expression of each hFcγR on the mouse leukocyte populations in the novel RHuFR mouse recapitulated the human expression pattern (Figure S2, Table S1). Furthermore, mice lacking each of the individual hFcγRs were isolated while breeding to create single human FcγR “knockout” strains in the Rag2−/− background (Table S2). Loss of the B and T cell populations in the FcγR Null, RHuFR, and RHuFR “knockout” strains was also confirmed (Figure S3).

The newly generated RHuFR mice were first used in a model of idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP), as a surrogate for in vivo antibody-dependent cytotoxicity by employing an anti-platelet hIgG1. The RHuFR mice achieved platelet depletion, comparable to what is reported for the immunocompetent human FcγR+ mice 7 (Figure S4A). This suggests that the introduction of Rag2 deficiency does not interfere with FcγR mediated function in these animals and that FcγR function has been maintained from the parental immunocompetent human FcγR+ mice. The RHuFR “knockout” strains were also used in the ITP model and overall, demonstrated little fluctuation in hFcγR mediated platelet depletion compared to the parental RHuFR strain (Figure S4B).

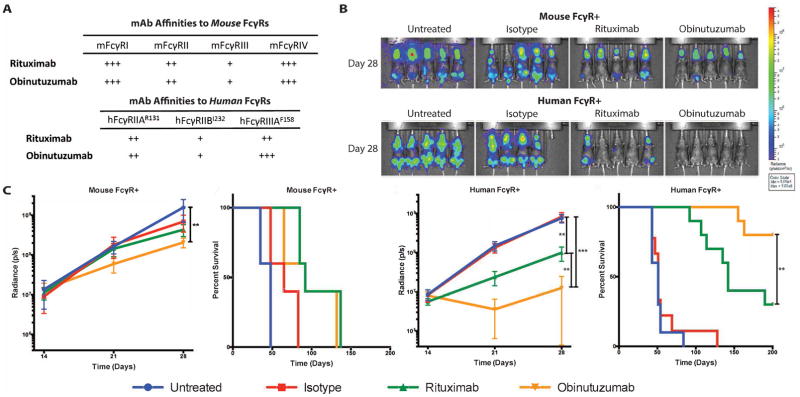

Next, to investigate the ability of RHuFR mice to more accurately mimic clinical observations for therapeutic cancer antibodies, we chose two commercially available anti-CD20 antibodies, rituximab and obinutuzumab, which substantially differ in human clinical activity. Rituximab contains a wild type hIgG1 heavy chain constant region, while obinutuzumab contains a hIgG1 heavy chain constant region with decreased levels of fucosylated oligosaccharides resulting in enhanced binding to hFcγRIIIA and thus enhanced ADCC activity. A recent Phase III study in patients with CLL demonstrated that the Fc enhanced obinutuzumab confers a significantly higher response rate and survival advantage over rituximab therapy9.

We first investigated antibody pharmacokinetics. For both antibodies, Rag2−/− mouse FcγR+ mice had prolonged antibody blood half-lives, while the RHuFR mice had extremely short antibody kinetics (Figure S5). Human FcγRI is the only high affinity human FcγR that binds soluble, monomeric IgG. The high degree of homology between human and mouse FcγRI, as well as their IgG binding affinity suggest that human FcγRI has likely limited contribution to the cytotoxic activity of anti-tumor mAbs in vivo6, 10. Indeed, for several therapeutic antibodies, clinical response to therapy has been shown to be associated with SNPs of the low affinity FcγRs, FcRγIIIa and FcγRIIa, but not with FcγRI. Furthermore, mechanistic studies on the role of human FcγRs in the in vivo activity of anti-CD20 antibodies revealed that cytotoxicity against tumor targets is mediated exclusively through FcγRIIIa-mechanisms.

Therefore, we employed the RHuFR derivative strain that lacks human FcγRI (RHuFR1−) to remedy this kinetic discrepancy (Figure S5), thereby allowing for an antibody-dosing regimen to compare therapeutic effects between the RHuFR1− and the Rag2−/− mouse FcγR+ mice. Importantly, the RHuFR1− mouse expresses all other human FcγRs in the same manner as in the RHuFR mice (Figure S6) and is functionally intact, showing identical platelet clearance to the RHuFR mouse in the ITP model (Figure S4B). Furthermore, since the main focus of this study is the generation of mouse strains for the study of Fc effector function in vivo, the humanization of FcRn was not necessary given that FcRn function is to regulate IgG half-life and not effector function.

Rag2−/− mice expressing either the mouse FcγRs or human FcγRs (RHuFR1−) were engrafted with the CD20+ Daudi human lymphoma cell line and treated with rituximab or obinutuzumab. The affinities of rituximab and obinutuzumab for the relevant mouse and human FcγRs were measured (Figure 2A, Figure S7). As FcγRI is not present in the mouse strains used, affinity values have been omitted for clarity. The Fc engineering of obinutuzumab results in a significant increase in affinity for hFcγRIIIA, with little to no increase in affinity for activating mouse FcγRs. In the mouse FcγR+ mice, no significant therapeutic response benefit for rituximab was observed, while obinutuzumab resulted in a less than 1 log decrease in overall tumor signal as compared to untreated (p=0.0072) (Figure 2B & 2C). However, obinutuzumab therapy did not confer a survival advantage over rituximab therapy in the mouse FcγR+ mice (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. The human FcγR+ RHuFR1− mouse is superior to the conventional Rag2−/− mouse in replicating rituximab versus obinutuzumab clinical outcomes.

(A) Relative affinities of the relevant mouse and human FcγRs. (B) Bioluminescence imaging of Rag2−/− mouse FcγR+ and RHuFR1− female mice at day 28. (C) Left two curves show total radiance signal (photons/second) and Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Rag2−/− mouse FcγR+ mice (n=5 mice/group). Obinutuzumab therapy resulted in a small reduction in overall tumor burden when compared to untreated mice (p=0.0072) and no difference in survival was observed between the two anti-CD20 mAb therapy groups. Right two curves show total radiance signal (photons/second) and Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all RHuFR1− mice (n= 9–10 mice/group). Obinutuzumab therapy demonstrated significant reductions in tumor burden compared to untreated and isotype (p<0.0001 for both). There was also a significant difference in overall tumor burden between rituximab and obinutuzumab treated groups (p=0.003) and a significant survival advantage for obinutuzumab therapy compared to rituximab therapy (p=0.0088).

In contrast, rituximab modestly slowed lymphoma growth in the RHuFR1− mice, while obinutuzumab achieved significant eradication of the lymphoma with a ~1 vs. ~2 log reduction in tumor burden from untreated, respectively (Figure 2B–C). Moreover, by Day 28, 9/10 mice on obinutuzumab therapy had no detectable tumor burden, while only 4/10 mice on rituximab therapy showed no detectable tumor (Figure S8). Both rituximab and obinutuzumab treatment resulted in increased median survival compared to untreated and isotype treated mice (Figure 2C). Moreover, a significant survival advantage for obinutuzumab vs. rituximab treated RHuFR1− mice was seen. These data directly mimic the enhanced human clinical response rates and prolonged progression free survival trends observed for obinutuzumab over rituximab9. Furthermore, these data support the importance of testing Fc enhanced therapeutic antibodies in the setting of the human FcγR network.

In contrast to the traditional immunodeficient model with mouse FcγRs, the RHuFR1− mice reproduced the clinical observations for rituximab vs. obinutuzumab therapy. In addition, the RHuFR derivative strains lacking one or more hFcγRs will allow for the probing of the individual roles of each receptor in both pharmacology and therapy, as demonstrated in the inflammatory ITP model. This is especially important to quickly identify the receptors responsible for mAb therapy in vivo and subsequently direct Fc engineering of the antibody. Furthermore, crossing these RHuFR “knockout” strains can quickly create mice containing combinations of human FcγR “knockouts” for probing receptor interactions and redundancy in function. Overall, these mice are tools to expand our understanding of the complexity of the human FcγR network and how individual antibody targets (e.g. epitope, target cell type, microenvironment, etc.) can greatly shape the observed therapeutic effect for a given antibody.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Michael Kharas provided the Hemavet machine and Dr. Joseph Sun supplied the anti-NK1.1 (PK136) antibody. Dr. Dmitry Pankov, Dr. Katja Behling, and Aaron Chang assisted with mouse work.

Funding: The work was supported by: a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F31 CA189305 to E.C.), NIH R01 CA55349, P01 CA33049, CCSG P30-008749 to D.A.S., The Tudor Fund, Lymphoma Foundation, and The Center for Experimental Therapeutics to D.A.S.; American Foundation for AIDS Research Mathilde Krim Fellowship in Basic Biomedical Research (109519-60-RKVA) to S.B., and the NIH P01 CA190174 and R35 CA196620 to J.V.R. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author contributions: E.C. conceived and performed mouse breeding and colony maintenance, flow cytometry characterization of new mice strains, ITP model experiments, lymphoma antibody therapy experiments, and authored the manuscript. S.B. contributed to the conception of breeding scheme and experimental plans, contributed mice and antibody resources, performed the antibody-FcγR SPR anaylsis, and contributed methods and edited the manuscript. G.M. and P.M contributed to mouse characterization experiments and edited the manuscript. K.S.T. performed statistical analysis, contributed to the methods, and edited the manuscript. J.V.R. contributed mice and other resources and edited the manuscript. D.A.S. contributed resources and helped guide the planning and execution of the experiments and edited the manuscript.

Competing interests: A patent has been filed by MSKCC encompassing these novel mouse strains.

References

- 1.Cartron G, et al. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcγRIIIa gene. Blood. 2002;99:754–758. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weng WK, Levy R. Two Immunoglobulin G Fragment C Receptor Polymorphisms Independently Predict Response to Rituximab in Patients With Follicular Lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:3940–3947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark MR. IgG Effector Mechanisms. Chemical Immunology. 1996;65:88–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent Immunoglobulin G Subclass Activity Through Selective Fc Receptor Binding. Science. 2005;310:1510–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1118948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosenthal J. Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotech. 2014;32:40–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nimmerjahn F, Bruhns P, Horiuchi K, Ravetch JV. FcγRIV: A Novel FcR with Distinct IgG Subclass Specificity. Immunity. 2005;23:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith P, DiLillo DJ, Bournazos S, Li F, Ravetch JV. Mouse model recapitulating human Fcγ receptor structural and functional diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:6181–6186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203954109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bournazos S, DiLillo DJ, Ravetch JV. In: Fc Receptors. Daeron M, Nimmerjahn F, editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2014. pp. 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goede V, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1101–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamaguchi Y, Xiu Y, Komura K, Nimmerjahn F, Tedder TF. Antibody isotype-specific engagement of Fcγ receptors regulates B lymphocyte depletion during CD20 immunotherapy. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203:743–753. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.