Abstract

Background

Initial reports of transbronchial cryobiopsy for diffuse parenchymal lung disease (DPLD) suggest the diagnostic yield approaches that of surgical lung biopsy (SLB) with an excellent safety profile. Centers performing cryobiopsy differ significantly in procedure technique; an optimal technique minimizing complications but still capable of diagnosing a wide range of DPLDs has not been established. We evaluated our practice of flexible bronchoscopic cryobiopsy in a primarily outpatient setting for patients who required a tissue diagnosis for DPLD of uncertain etiology.

Methods

Consecutive patients with indeterminate DPLD who underwent bronchoscopic cryobiopsy at a large academic medical center from January 2012 to August 2015 were retrospectively analyzed. Rates of confident histopathological diagnosis, confident multidisciplinary consensus diagnosis, management change, and complications were determined.

Results

One hundred four cases were identified. Confident histopathological diagnoses were established in 44% (46/104) and confident multidisciplinary consensus diagnoses in 68% (71/104). Usual interstitial pneumonia (19/104) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (22/104) were the most common histopathological and consensus diagnoses, respectively. Five subjects proceeded to SLB after cryobiopsy which was diagnostic in three. Results of cryobiopsies changed management in 70% (73/104). Complications occurred in 8 cases with no death.

Conclusions

Cryobiopsy during outpatient flexible bronchoscopy facilitated confident multidisciplinary consensus diagnosis of DPLD in more than two thirds of cases, and appears sufficient to establish the histopathologic diagnosis of UIP, with a complication rate that compares favorably to that reported for SLB.

Keywords: Cryobiopsy, Transbronchial Biopsy, Interstitial Lung Disease, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Transbronchial lung biopsy with a cryoprobe, or cryobiopsy, is a novel technique allowing bronchoscopic retrieval of lung biopsies an order of magnitude larger than conventional forceps-based techniques, without crush artifact2,3. Initial reports have explored the diagnostic capability of cryobiopsy in diffuse parenchymal lung disease (DPLD). Conventional forceps transbronchial biopsies, diagnostic in only a third of cases4, are generally viewed as insufficient in this setting; current guidelines suggest surgical lung biopsy (SLB) be pursued when clinical and radiographic features are insufficient to establish a confident diagnosis5,6. However, the risks associated with SLB in this population7–10 are sometimes perceived as prohibitive by clinicians or DPLD patients. In most centers, the most common diagnosis in patients presenting with DPLD is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), which relies on clinical criteria and a specific histologic or radiologic pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)5,11. As high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest is frequently insufficient for confident diagnosis, and newly-available therapeutics have changed management strategies for IPF, a safe alternative to SLB is urgently needed. Cryobiopsy appears ideally positioned to meet this need. However, data remain limited and the techniques used poorly standardized12. Whether transbronchial cryobiopsy via outpatient flexible bronchoscopy is sufficient to establish histopathological diagnoses in DPLD, including UIP, remains unclear.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection and Data Extraction

This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (IRB# 151099) with a waiver of informed consent. Our institution transitioned from SLB to cryobiopsy as the predominant initial lung biopsy modality in indeterminate DPLD in January 2012. Records of patients who underwent cryobiopsy through the date of IRB approval (August 17, 2015) were reviewed; biopsies to characterize DPLD were included. Each underwent the procedure once. Pertinent data were retrospectively extracted from the medical record by two authors (R.J.L. and T.M.T.). HRCTs within one month of cryobiopsy were classified per current guidelines5 as UIP pattern, possible UIP, or inconsistent with UIP by a thoracic radiologist. Subjects included in an early report of cryobiopsy from our institution are included in this analysis, as management changes in these subjects were not previously assessed1.

Bronchoscopy and Cryobiopsy Procedure

Procedures were performed by an attending interventional pulmonologist or fellow under direct supervision in a dedicated bronchoscopy operating room with standard monitoring at least seven days after last antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication use. A certified registered nurse anesthetist provided intravenous deep sedation and adequate spontaneous respiratory effort was maintained.

Following topical anesthesia of the oropharynx, vocal cords, and upper trachea with lidocaine, each subject was intubated with an 8.5 mm wire-reinforced endotracheal tube (Smiths Medical, St Paul, MN, USA) advanced over flexible bronchoscope (Olympus XT180 or BF-1TH190, Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA). This style of ETT was chosen for its combination of flexibility and strength in this procedure with rapid exits from and entries into the airway, and the ease with which it can be advanced into either mainstem bronchus in the event of significant bleeding. Oxygen was delivered per tube but the cuff was not inflated.

Areas of significant abnormality on pre-procedure CT scan were targeted. The lower lobes were preferentially biopsied; each biopsy was taken from a different segment. Prior to each biopsy, a fluoroscopic reference image was recorded with the bronchoscope wedged in the desired segment to permit fluoroscopic navigation back to the segment in the event of significant bleeding. A 1.9 mm diameter carbon dioxide-cooled cryoprobe measuring 90 cm in length (ERBE Elektromedizin GmBH, Tübingen, Germany) was then advanced until resistance was felt or the probe was seen fluoroscopically to reach the pleura. After pulling back 1.5–2 centimeters, the cryoprobe was activated for 4–5 seconds before cryoprobe and bronchoscope were pulled out of the airway en-bloc. The cryobiopsy was submerged in room temperature saline to rapidly thaw and release the tissue, allowing the cryoprobe to be removed as the bronchoscope was reintroduced into the airway. The bronchoscope was re-wedged in the biopsied segment, iced saline was administered, and tamponade was maintained until hemostasis was achieved. Two to three cryobiopsies were sought per case at the discretion of the operator.

Bronchial blockers and a rigid bronchoscope were immediately available to manage complications. Starting January 2015, we began employing prophylactic bronchial blockade using a balloon occlusion catheter (Fogarty, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) or endobronchial blocker (Arndt, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) as previously described13 while the bronchoscope was out of the airway after each biopsy, in response to a major hemorrhage.

Tissue Processing and Pathology

Cryobiopsies were immediately transferred from saline to 10% formalin, then embedded in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, with additional stains at the discretion of the pathologist. All slides were reviewed by one of two expert lung pathologists. Diagnoses of UIP were made in accordance with current guidelines5; confident non-UIP diagnoses (e.g. other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, granulomatous diseases, bronchiolitides) were based on identification of characteristic features14,15.

Complications

Major hemorrhage was scored if additional airway management or bronchial blockade (other than prophylactic use) was required, the procedure was stopped early, transfusion was required, or hemodynamic instability or respiratory failure resulted. Respiratory failure was defined as hypoxemia requiring initiation or escalation of supplemental oxygen or increased level of monitoring for respiratory status (outpatient to inpatient, inpatient floor to ICU). Pneumothoraces, unplanned hospital admissions, and periprocedural arrhythmias were also recorded.

Diagnostic Yield and Management Changes

Two authors with experience in DPLD (R.J.L. and J.A.K.) independently scored the confidence with which diagnoses were established. A confident histopathological diagnosis was scored if the pathologist identified a specific disease process or strongly favored one disease over, at most, one additional consideration. A confident consensus diagnosis was scored if both retrospective reviewers independently agreed that the multidisciplinary consensus diagnosis was reached with a high degree of certainty and no contradictory data was obtained during the clinical follow-up of that subject. The same authors independently reviewed medical records for management changes attributed to cryobiopsy results.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies. Between-group comparisons were conducted using Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test or Pearson χ2 for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. A two-sided p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics v.23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Subject, Procedure, and Cryobiopsy Characteristics

A total of 104 subjects underwent cryobiopsy for the diagnosis of a DPLD during the study interval. Baseline subject characteristics are summarized in Table 116. The majority (88%) were outpatients at the time of the procedure. Most were referrals from our institution’s Interstitial Lung Disease Clinic when a DPLD was insufficiently characterized by clinical and radiographic data according to the evaluating pulmonologist after review of the HRCT with thoracic radiology. Referrals from outside our institution were evaluated in Interventional Pulmonary clinic and discussed by our multidisciplinary DPLD committee prior to the procedure. Pre-procedure HRCTs demonstrated a UIP pattern in 7 cases, possible UIP in 11, and were inconsistent with UIP in 86. Subjects with UIP pattern on HRCT proceeded to cryobiopsy because of clinical concern for an alternate diagnosis (e.g. hypersensitivity pneumonitis in the context of ongoing avian exposure). A total of 228 cryobiopsies were obtained with mean greatest dimension of 6.9 mm. Alveoli were absent from only one case and bronchioles from three. Lower lobes were most frequently biopsied; in 21 cases (20%), the RUL was biopsied in addition to the RLL. Additional biopsy features are detailed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline Subject Characteristics

| Characteristic | Study subjects (n=104) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr† | 58.2 (20 – 83) |

| Male Gender | 58 (55.8) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 52 (50) |

| Current | 11 (10.6) |

| Former | 41 (39.4) |

| Pack/years smoked | 20.1 ± 20.4 |

| Outpatient | 91 (87.5) |

| HRCT: UIP designation | |

| UIP pattern | 7 (6.7) |

| Possible UIP | 11 (10.6) |

| Inconsistent with UIP | 86 (82.7) |

| Pulmonary Function Tests | |

| FVC, L | 2.8 ± 0.97 |

| FVC, % predicted | 70.2 ± 17.9 |

| FEV1, L | 2.2 ± 0.69 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 71.2 ± 17.2 |

| TLC, L | 4.3 ± 1.3 |

| TLC, % predicted | 70.2 ± 18.3 |

| DLCO, mm/min/mmHg | 14.6 ± 7.0 |

| DLCO, % predicted | 59.1 ± 22.6 |

| Respiratory status | |

| SpO2 | 96.3 ± 5 |

| Supplemental oxygen at baseline | 18 (17.3) |

| S:F ratio <315‡ | 9 (8.6) |

Values presented as number (percentage) or mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise noted. DLCO is reported corrected for hemoglobin, when available. DPLD = diffuse parenchymal lung disease; FVC = forced vital capacity; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in the first second; TLC = total lung capacity; DLCO = diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; SpO2 = pulse oximetric saturation; S:F ratio = SpO2 divided by fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2).

Presented as mean (range).

Correlates with PaO2:FiO2 ratio of 300.16

Table 2.

Procedure and Biopsy Characteristics and Complications

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Cryobiopsies per case | 2.2 ± 0.6 (1–4) |

| Locationa | |

| RLL | 179 (79) |

| LLL | 28 (12) |

| RUL | 21 (9) |

| Prophylactic bronchial blockade employedb | 16 (15) |

| Greatest dimension (mm) | 6.9 ± 4.1 (1–31) |

| Alveoli absentb | 1 (1) |

| Bronchioles absentb | 3 (3) |

| Complicationsc | |

| Major hemorrhage | 4 (4) |

| Pneumothorax | 3 (3) |

| Unplanned hospital admission | 6 (6) |

| Respiratory failure | 2 (2) |

Data presented as number (%) or mean ± SD (range).

Denominator = total biopsy count (n=228).

Denominator = total number of cases (n=104).

More than one complication occurred in some cases; 8 cases in total (7.7%) had at least one complication

Diagnostic Yields and Management Changes

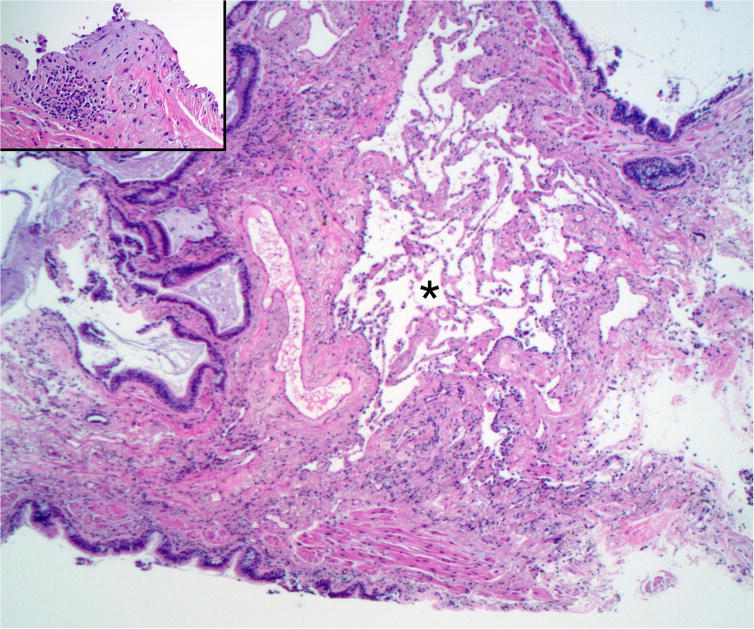

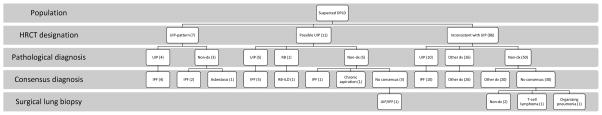

Cryobiopsy established a confident histopathological diagnosis in 46 of 104 cases (44.2%) and a confident consensus diagnosis in 71 (68.3%); see Table 3. All cases with a confident histological diagnosis received a confident consensus diagnosis upon review by multidisciplinary committee. In an additional 25 cases, less-than-definite histopathological findings still allowed for a confident consensus diagnosis when considered alongside clinical and radiographic data. UIP, the most common histopathological diagnosis (Figure 1), comprised 18% of all cases and 41% of those with a histopathologic diagnosis. IPF was the most common consensus diagnosis, comprising 21% of the series and 31% of those in which a confident consensus diagnosis was established. Of the 18 subjects with UIP pattern or possible UIP pattern on HRCT, half received a histological diagnosis of UIP and two-thirds a consensus diagnosis of IPF (Table 4). There were 10 diagnoses of UIP among 86 subjects with HRCTs interpreted as inconsistent with UIP pattern. Surgical lung biopsy, pursued in five subjects without a confident diagnosis after cryobiopsy, established three additional diagnoses: UIP/IPF, T-cell lymphoma, and organizing pneumonia. A flow chart of the diagnostic process is depicted by Figure 2.

Table 3.

Diagnoses Established by Cryobiopsy

| Diagnosis | Histopathological diagnoses (n=46) | Consensus diagnoses (n=71) |

|---|---|---|

| IPF/UIP | 19 | 22† |

| HP | 3 | 8 |

| Chronic aspiration | 7 | |

| CB | 4 | 4 |

| CTD-ILD | 4 | |

| NSIP | 2 | 3 |

| BO | 3 | 3 |

| Sarcoidosis | 2 | 3 |

| Malignancy | 2 | 2† |

| RB/RB-ILD | 2 | 2 |

| OP | 4 | |

| due to drug | 2 | |

| Cryptogenic | 2† | |

| Normal lung / no DPLD | 1 | 2 |

| DIP | 1 | 1 |

| FB | 1 | 1 |

| PAP | 1 | 1 |

| Silicosis | 1 | 1 |

| Fungal infection | 1 | |

| Asbestosis | 1 | |

| Drug Pneumonitis | 1 |

Presented as number of diagnoses. IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; UIP = usual interstitial pneumonia; HP = hypersensitivity pneumonitis; CB = constrictive bronchiolitis; CTD-ILD = connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease; NSIP = nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; BO = bronchiolitis obliterans; RB = respiratory bronchiolitis; OP = organizing pneumonia; DPLD = diffuse parenchymal lung disease; DIP = desquamative interstitial pneumonia; FB = follicular bronchiolitis; PAP = protein alveolar proteinosis;

An additional case, not included in the annotated count, was later diagnosed by surgical lung biopsy.

Figure 1.

Representative image of a cryobiopsy diagnostic of UIP. Asterisk: an island of intact alveolar tissue. The left half of the image is end-stage honeycomb lung. Inset: a fibroblastic focus at higher magnification. Original magnification 12.5× (main) and 42.5× (inset).

Table 4.

Cryobiopsy Diagnostic Results Stratified by HRCT UIP designation

| UIP designation | Pathological diagnosis | Clinical diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UIP | Other | Non-dx | IPF | Other | Non-dx | |

| UIP pattern (n=7) | 4 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 1a | 0 |

| Possible UIP (n=11) | 5 | 1b | 5 | 6 | 2c | 3 |

| Inconsistent with UIP (n=86) | 10d | 26e | 50 | 10 | 46e | 30 |

Data presented as frequencies.

Asbestosis

Respiratory Bronchiolitis

Respiratory Bronchiolitis-ILD, chronic aspiration

Inconsistent with UIP for lack of basilar predominance/significant upper lobe involvement (4), air trapping >3 lobes (3), significant ground glass (2), peribronchovascular predominance (1)

See Table 3

Figure 2.

Diagnostic flow chart incorporating HRCT, histopathological, multidisciplinary consensus, and surgical lung biopsy (when applicable) diagnoses.

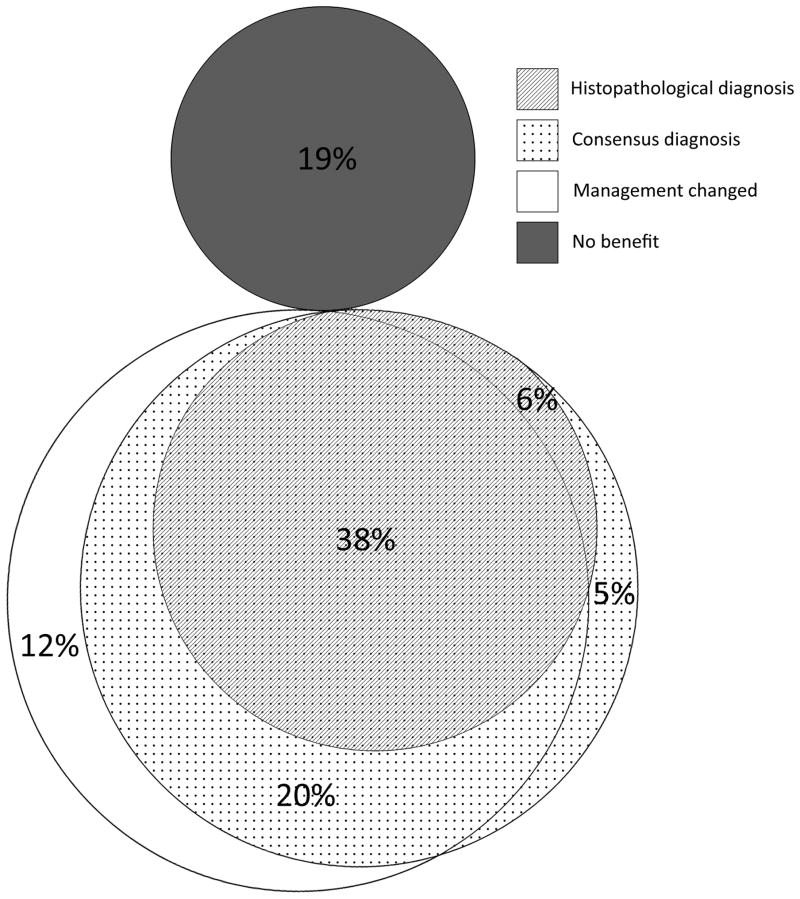

Cryobiopsy changed management in 73 cases (70%), more often when cryobiopsy established a clinical diagnosis than when it did not (88% vs. 39%; 95% CIs, 79–96% vs. 21–58%; p<0.01). Changes are detailed in Table 5; the relationship between histopathological diagnosis, consensus diagnosis, and management change is illustrated by Figure 317.

Table 5.

Management Changes Attributed to Cryobiopsy

| Start a medication | Incidence, No. |

|---|---|

| Systemic corticosteroids | 19 |

| IPF therapy (pirfenidone/nintedenib) | 14 |

| Immunosuppressant | 11† |

| Chronic macrolide | 9 |

| IPF clinical trial | 7 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid | 4 |

| Chemotherapy | 2 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 2 |

| Antibiotic (non-macrolide) | 1 |

| Inhaled GM-CSF | 1 |

| Stop a medication | |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 1 |

| Referred to: | |

| Gastroenterology | 7 |

| Lung transplant | 3 |

| Rheumatology | 2 |

| Thoracic surgery | 1‡ |

| Hematology/Oncology | 1 |

| Palliative Care | 1 |

| Other | |

| Avian eviction | 3 |

| Mechanical airway clearance | 1 |

More than one management change occurred in several cases. GM-CSF = granulocyte macrophophage colony stimulating factor.

Includes azathioprine (4), mycophenolate mofetil (2), cyclophosphamide (2), methotrexate (1), infliximab (1), hydroxychloroquine (1).

Not including five referrals for surgical lung biopsy after nondiagnostic cryobiopsy.

Figure 3.

Area-proportional Euler diagram depicting the relationship between histopathological diagnosis, consensus diagnosis, and management change.

Safety

Major complications occurred in 8 cases (7.7%). There were four major hemorrhages. Two were well-controlled with bronchoscopic tamponade, iced saline, and lung-down positioning but stopped the procedure after one biopsy; estimated blood loss (EBL) was 100 ml in each case. The third, occurring after the third biopsy, resulted in brief hypoxemic PEA arrest requiring cuff-up positive pressure ventilation, bronchoscopic tamponade and decubitus positioning with EBL 300 ml; this subject was extubated the next morning with full neurologic recovery. In response, prophylactic bronchial blockade was employed after each biopsy in the final 16 cases in this series. Re-inflation of this blocker after prophylactic use in one of these latter subjects was scored as the fourth major hemorrhage, as our pre-specified definition of major hemorrhage included bleeding necessitating bronchial blockade for control. In this case, deflation of the bronchial blocker revealed a brisk bleed following the first biopsy; re-inflating the blocker established rapid control of the hemorrhage and hemostasis was achieved after three minutes with EBL 50 ml. Further biopsies were then pursued. Minimal or minor bleeding occurred in the remaining 100 cases; overall mean EBL was 22 ± 19 mL (range, 0–75).

Three pneumothoraces occurred, including one in the fourth major bleed subject, all requiring small-bore chest tube thoracostomy and 1–2 day hospitalizations. There were two episodes of respiratory failure: the post-arrest subject and an inpatient who developed bronchospasm hours post-procedure prompting brief MICU observation. The final serious complication was a subject admitted for overnight observation after returning several hours after discharge with malaise but who did not have pneumothorax, new hypoxemia, or hemoptysis.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis of 104 consecutive transbronchial cryobiopsy procedures evaluating indeterminate DPLD, we determined that: 1) cryobiopsy established confident histopathological diagnoses in 46 cases (44%) and confident consensus diagnoses in 71 (68%); 2) eighteen percent of subjects received a histopathological diagnosis of UIP and 21% received a consensus diagnosis of IPF; 3) cryobiopsy changed management in 70% of cases; 4) the rate of major complications was 7.7%.

The prevalence of UIP/IPF in existing series of cryobiopsy for DPLD varies widely, likely reflecting variations in study populations and procedural aspects18. We diagnosed 22 of 104 subjects with IPF for a diagnostic prevalence of 21%, higher than reported in most previous studies2,18–24. Cryobiopsies in 19 of these 22 subjects were definitive for UIP. Histologic features in the other three cases were consistent with UIP but not sufficient for a confident diagnosis; all three were felt to have IPF by multidisciplinary committee considering clinical and radiographic data.

The only other large series with a high prevalence of UIP/IPF (31%)18 used a markedly different cryobiopsy technique: 2.4 mm diameter cryoprobe (vs. our 1.9 mm), biopsy <10 mm from the pleura (vs. 15–20 mm from the pleura), most biopsies in only one segment (vs. different segments, and in 21 cases, different lobes), and intubation with a rigid bronchoscope (vs. orotracheal intubation facilitated by flexible bronchoscope). Despite diagnosing UIP/IPF at similar rates, we note a significantly lower incidence of pneumothorax (2.9% vs. 20.2%) and hospitalization (5.8% vs. 94.6%) in our series. We did have four major hemorrhages (3.8%) and have adopted prophylactic bronchial blockade following each biopsy in all patients. Our overall complication rate of 7.7% compares favorably with the previously reported range of 0–25%2,18–24.

The relationship between the incidence of the two primary complications of cryobiopsy, pneumothorax and significant hemorrhage, has been hypothesized to be reciprocal; higher rates of pneumothorax have been reported when the cryoprobe is activated very close to the pleura18,23,25, while more proximal biopsies near larger-caliber vessels might be at higher risk for major hemorrhage12. Pneumothorax rates might also be influenced by ventilation strategy, with higher risk of pneumothorax hypothesized in the setting of positive pressure or jet ventilation. For this reason, we utilized deep sedation rather than general anesthesia to permit maintenance of adequate spontaneous ventilation around the cuff-down ETT used in our subjects. More study is necessary to determine an optimal technique which limits the risk of these competing complications while maximizing diagnostic yield.

Our overall consensus diagnostic yield of 68% (71 of 104) falls within the previously reported range of 50–98%2,20–23. Our histopathological diagnostic yield of 44% (46 of 104), however, falls short of the published range of 51–83%18–24 in prior studies of cryobiopsy. We offer several potential explanations. We performed cryobiopsy for any diffuse process if an indication existed for SLB and declined to biopsy only one referral (on a high level of mechanical ventilatory support) during the study period. We therefore cryobiopsied a wide range of diffuse lung diseases, not just fibrotic disease suspicious for IPF or other idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (entities with fairly robust histopathological and clinical-radiological-pathological diagnostic criteria). As shown in Table 4, histopathological diagnostic rate was higher in cases with HRCT consistent with UIP pattern (4 of 7; 57%) and Possible UIP pattern (6 of 11; 55%) than those with HRCT inconsistent with UIP (36 of 86; 42%). Despite this, we were still able to establish 19 different specific diagnoses, compared to a range of 7–15 diagnoses in prior investigations2,18–23. This broader scope of pathology might also explain why our diagnostic prevalence of IPF was not higher; UIP was not suspected in subjects with HRCTs concerning for primary small airway processes or diffuse nodules but these patients underwent cryobiopsies nonetheless and were included in this analysis, whereas they were excluded in many prior investigations. Finally, we employed a more stringent definition of histopathological diagnosis compared to several prior studies21,22, by including only specific idiopathic interstitial pneumonias and other well-defined entities (e.g. malignancy, sarcoidosis, protein alveolar proteinosis14). Our diagnostic rates are well above that reported for traditional forceps transbronchial lung biopsy, with histopathological and consensus diagnostic rate 20–32% in this setting4,26.

No prior studies report how often cryobiopsy affects clinical management. A management change attributed to cryobiopsy occurred in 70% of our cases. Expectedly, changes were more likely if cryobiopsy established a diagnosis, though 39% of nondiagnostic cryobiopsies still led to management changes. As a result, four out of five subjects benefited from cryobiopsy in the form of a diagnosis or a management change (frequently, both), depicted by Figure 3.

Five subjects without a consensus diagnosis following cryobiopsy proceeded to SLB. Surgical pathology was consistent with cryobiopsy pathology (nonspecific small airway-centric inflammation) in two cases and no diagnosis was rendered. Two were clear examples of cryobiopsy sampling error: a case of UIP/IPF in which no alveolated parenchyma was recovered (only one biopsy obtained due to significant bleeding; likely due to inadvertently proximal biopsy location) and a case of organizing pneumonia with particularly patchy distribution on HRCT. In the fifth case, cryobiopsy demonstrated a necrotic malignancy subsequently diagnosed as T-cell lymphoma by SLB. Surgical lung biopsy was offered but declined by the patient in several additional cases with still-indeterminate disease following cryobiopsy.

The primary strength of this study is a relatively high diagnostic prevalence of UIP/IPF using a more conservative outpatient-based flexible bronchoscopic approach than other centers reporting similar rates of UIP/IPF, where rigid bronchoscopy is typically performed and complication rates are higher. This was accomplished despite pursuing cryobiopsy in a broader range of subjects indicated for SLB, including those with suspected primary small airway disease or diffuse nodules. Strict diagnostic definitions in accordance with current guidelines were used to avoid inflating diagnostic yields. All cases were reviewed by a multidisciplinary team of pulmonologists, radiologists, and pathologists at this center with extensive interstitial lung disease experience. Our procedural technique has been meticulously detailed to permit comparison with other practices.

There are several important limitations in the current study. Although the confidence with which diagnoses were established was not always prospectively documented, we attempted to limit bias in the retrospective interpretation of these diagnoses this by having multiple authors independently assess the confidence in each and review clinical follow-up to ensure no contradicting data arose post-cryobiopsy. The single-center nature of this series may limit generalizability of these results, though diagnoses were established based on current consensus statement guidelines. While our sample size is relatively large compared to many other studies of cryobiopsy, this series is still of modest size. No direct comparison to gold standard SLB for histopathological diagnosis is offered, so safety and yield comparisons to SLB rely on previously published data. Large studies of SLB suggest a range of operative risk depending on preoperative status and comorbidities10,27; our sample was not large enough to permit robust stratification of risk on this basis. Accordingly, comparison between cryobiopsies and SLB remain subject to significant bias at this time. Finally, procedures were performed or supervised by an interventional pulmonologist; complication rates could be higher with less experienced operators. Given the small but clearly present risk of life-threatening hemorrhage during this procedure, in its current state we feel strongly that its performance should be limited to experienced operators with advanced bronchoscopic training who are adept at managing serious hemorrhage.

Transbronchial cryobiopsy continues to show promise as a relatively safe alternative to SLB for the diagnosis of indeterminate DPLD. The outpatient-based flexible bronchoscopic approach we utilized appears capable of diagnosing UIP/IPF as well as a wide range of other diseases. Comparison to SLB remains challenging; directly comparative research is warranted and will help elucidate where cryobiopsy is best situated in the diagnostic algorithm for indeterminate DPLD. Standardization of a cryobiopsy technique that optimizes yield and minimizes complications should be proposed by an expert panel and supported by additional data.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This work was supported by NIH HL092870 (TSB), HL085317 (TSB), HL130595 (JAK), Francis Family Foundation (JAK), Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (JAK), Vanderbilt Faculty Research Scholars Program (JAK), Department of Veterans Affairs (TSB), and NCATS/HIN UL1TR000445 (database).

Guarantor statement: Robert J. Lentz had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, including and especially any adverse effects.

Author contributions: Study concept and design: RJL, TMT, FM, OBR. Acquisition of data: RJL, TMT, JAK, KLS, ASH, JEJ. Analysis and interpretation of data: RJL, TMT, JAK, TSB, FM, OBR. Drafting of the manuscript: RJL, TMT. All authors participated in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and provided final approval to submit this version of the manuscript and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: OBR reported consulting for Covidien/Medtronic and serving on an advisory board for Olympus, both outside the scope of this work. Remaining authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding/role of sponsors: This work was supported by NIH HL092870 (TSB), HL085317 (TSB), HL130595 (JAK), Francis Family Foundation (JAK), Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (JAK), Vanderbilt Faculty Research Scholars Program (JAK), Department of Veterans Affairs (TSB), and NCATS/HIN UL1TR000445 (database). No funding source had any role in the design or analysis of this research or in the drafting of this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS LIST

- DLPD

Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease

- HRCT

High-Resolution Computed Tomography (scan of the chest)

- IPF

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- SLB

Surgical Lung Biopsy

- UIP

Usual Interstitial Pneumonia

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statements: OBR reported consulting for Covidien/Medtronic and serving on an advisory board for Olympus, both outside the scope of this work. Remaining authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Notation of prior publication/presentation: Diagnostic results of the first 25 cryobiopsy procedures performed at our institution were previously described1. These cases are re-analyzed in this manuscript as management changes derived from these procedures were not previously assessed. An abridged version of this work was presented at the American Thoracic Society 2016 International Conference (on May 16, 2016).

References

- 1.Kropski JA, Pritchett JM, Mason WR, et al. Bronchoscopic Cryobiopsy for the Diagnosis of Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e78674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babiak A, Hetzel J, Krishna G, et al. Transbronchial Cryobiopsy: A New Tool for Lung Biopsies. Respiration. 2009;78(2):203–208. doi: 10.1159/000203987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griff S, Ammenwerth W, Schönfeld N, et al. Morphometrical analysis of transbronchial cryobiopsies. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:53. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berbescu EA, Katzenstein A-LA, Snow JL, Zisman DA. Transbronchial biopsy in usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest. 2006;129(5):1126–1131. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells AU, Hirani N on behalf of the BTS Interstitial Lung Disease Guideline Group, a subgroup of the British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee, in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Interstitial lung disease guideline. Thorax. 2008;63(Supplement 5):v1–v58. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.101691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fibla JJ, Brunelli A, Cassivi SD, Deschamps C. Aggregate risk score for predicting mortality after surgical biopsy for interstitial lung disease. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15(2):276–279. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackhall V, Asif M, Renieri A, et al. The role of surgical lung biopsy in the management of interstitial lung disease: experience from a single institution in the UK. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;17(2):253–257. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y-C, Wu C-T, Hsu H-H, Huang P-M, Chang Y-L. Surgical lung biopsy for diffuse pulmonary disease: Experience of 196 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(5):984–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchinson JP, Fogarty AW, McKeever TM, Hubbard RB. In-Hospital Mortality after Surgical Lung Biopsy for Interstitial Lung Disease in the United States, 2000 to 2011. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(10):1161–1167. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1632OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nalysnyk L, Cid-Ruzafa J, Rotella P, Esser D. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: review of the literature. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21(126):355–361. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00002512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poletti V, Hetzel J. Transbronchial Cryobiopsy in Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease: Need for Procedural Standardization. Respiration. 2015;90(4):275–278. doi: 10.1159/000439313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hohberger LA, DePew ZS, Utz JP, Edell ES, Maldonado F. Utilizing an Endobronchial Blocker and a Flexible Bronchoscope for Transbronchial Cryobiopsies in Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease. Respiration. 2014;88(6):521–522. doi: 10.1159/000368616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Update of the International Multidisciplinary Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryu JH. Classification and approach to bronchiolar diseases. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12(2):145–151. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000208455.80725.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Ware LB. Comparison of the SpO2/FIO2 ratio and the PaO2/FIO2 ratio in patients with acute lung injury or ARDS. Chest. 2007;132(2):410–417. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Micallef L, Rodgers P. euler APE: Drawing area-proportional 3-Venn diagrams using ellipses. PloS One. 2014;9(7):e101717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravaglia C, Bonifazi M, Wells AU, et al. Safety and Diagnostic Yield of Transbronchial Lung Cryobiopsy in Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Diseases: A Comparative Study versus Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lung Biopsy and a Systematic Review of the Literature. Respiration. 2016;91(3):215–227. doi: 10.1159/000444089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griff S, Schönfeld N, Ammenwerth W, et al. Diagnostic yield of transbronchial cryobiopsy in non-neoplastic lung disease: a retrospective case series. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pajares V, Puzo C, Castillo D, et al. Diagnostic yield of transbronchial cryobiopsy in interstitial lung disease: A randomized trial: Transbronchial cryobiopsy. Respirology. 2014;19(6):900–906. doi: 10.1111/resp.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernández-González F, Lucena CM, Ramírez J, et al. Cryobiopsy in the Diagnosis of Diffuse Interstitial Lung Disease: Yield and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51(6):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fruchter O, Fridel L, El Raouf BA, Abdel-Rahman N, Rosengarten D, Kramer MR. Histological diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases by cryo-transbronchial biopsy. Respirol Carlton Vic. 2014;19(5):683–688. doi: 10.1111/resp.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagmeyer L, Theegarten D, Wohlschläger J, et al. The role of transbronchial cryobiopsy and surgical lung biopsy in the diagnostic algorithm of interstitial lung disease: Cryobiopsy in interstitial lung disease. Clin Respir J. 2015 doi: 10.1111/crj.12261. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ussavarungsi K, Kern RM, Roden AC, Ryu JH, Edell ES. Transbronchial Cryobiopsy in Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease: Retrospective Analysis of 74 Cases. Chest. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casoni GL, Tomassetti S, Cavazza A, et al. Transbronchial Lung Cryobiopsy in the Diagnosis of Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Diseases. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e86716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheth JS, Belperio JA, Fishbein MC, et al. Utility of Transbronchial versus Surgical Lung Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Suspected Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease. Chest. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raj R, Brown KK. Mortality Related to Surgical Lung Biopsy in Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease. The Devil Is in the Denominator. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(10):1082–1084. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2488ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]