Abstract

Background

Essential tremor (ET) is among the most common neurological diseases. Postmortem studies have noted a series of pathological changes in the ET cerebellum. Heterotopic Purkinje cells (PCs) are those whose cell body is mis-localized in the molecular layer. In neurodegenerative settings, these are viewed as a marker of the progression of neuronal degeneration.

Objective

We (1) quantify heterotopias in ET cases vs. controls, (2) compare ET cases to other cerebellar degenerative conditions (Spinocerebellar ataxia [SCA] 1, 2, 3, and 6), (3) compare these SCAs to one another, and (4) assess heterotopia within the context of associated PC loss in each disease.

Methods

Heterotopic PCs were quantified using a standard LH&E stained section of neocerebellum. Counts were normalized to PC layer length (n-heterotopia count). It is also valuable to consider PC counts when assessing heterotopia, as loss of PCs extends both to normally located as well as heterotopic PCs. Therefore, we divided n-heterotopias by PC counts.

Results

There were 96 brains (43 ET, 31 SCA [12 SCA1, 7 SCA2, 7 SCA3, 5 SCA6] and 22 controls). The median number of n-heterotopias in ET cases was two times higher than that of controls (2.6 vs. 1.2, p <0.05). The median number of n-heterotopias in the various SCAs formed a spectrum, with counts being highest in SCA3 and SCA1. In analyses that factored in PC counts, ET had a median n-heterotopia/Purkinje cell count that was 3 times higher than controls (0.35 vs. 0.13, p < 0.01), and SCA1 and SCA2 had counts that were 5.5 and 11 times higher than controls (respective p < 0.001). The median n-heterotopia/PC count in ET was between that of the controls and the SCAs. Similarly, the median PC count in ET was between that of the controls and the SCAs; the one exception was SCA3, in which the PC population is well-known to be preserved.

Conclusions

Heterotopia is a disease-associated feature of ET. In comparison, several of the SCAs evidenced even more marked heterotopia, although a spectrum existed across the SCAs. The median n-heterotopia/PC count and median PC in ET was between that of the controls and the SCAs; hence, in this regard, ET could represent an intermediate state or a less advanced state of spinocerebellar atrophy.

Keywords: essential tremor, spinocerebellar ataxia, cerebellum, neurodegenerative, Purkinje cell, pathology, heterotopia

Introduction

Essential tremor (ET) is among the most common adult-onset neurological diseases [1–3]. Kinetic tremor is the hallmark clinical feature of the disease [4], although patients may exhibit a range of additional features, including intention tremor [5,6], gait ataxia [7–10], eye movement abnormalities [11,12], and problems with motor timing [13], which indicate an abnormality in cerebellar function [14]. Neuroimaging studies consistently point to functional, metabolic, or structural abnormalities of the ET cerebellum [15–19].

Recent controlled postmortem studies have noted a series of pathological changes in the ET cerebellum, which reinforces the notion that the cerebellum is of patho-mechanistic importance in ET [20]. Among these changes are an increase in torpedoes and associated Purkinje cell (PC) axonal pathologies [21,22] and abnormal basket cell axons with a dense and tangled appearance (“hairiness”) surrounding the PC soma and elongated processes extending past the PC axon initial segment [23,24]. In addition, we have reported PC loss [21,25], a finding that has been variably reproduced [26–28]. In one additional study, the changes included heterotopic PCs [29]. Heterotopic PCs are those whose cell body is mis-localized in the molecular layer.

In the normal human cerebellum, PCs form a monolayer that lies in between the molecular and granular layers [29]. The proper anatomical location of different cell types within each of these layers is important for normal cerebellar function [29]. The mechanistic significance of heterotopic PCs is unknown; however, these are typically observed in either neurodevelopmental or neurodegenerative disorders [30–37]. In cerebellar degenerative disorders such as spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) 1 or 6, heterotopic PCs can occur along with PC loss [31,32], suggesting that in general they could either be a precursor to PC loss or a consequence of PC loss. Indeed, in SCA1 transgenic mice, PC heterotopias are seen along with PC dendritic thinning and are viewed as a marker of the progression of neuronal degeneration in that disease model [35].

Although the presence of heterotopic PCs has been demonstrated in one study of ET cases [29], the finding has yet to be reproduced. It also remains to be determined whether the extent of heterotopia in ET is similar or less than that seen in other disorders characterized by marked cerebellar degeneration. Furthermore, study of the association of heterotopic PCs with PC loss is rudimentary [29], and the relative presence of PC loss is likely to impact the number of heterotopic PCs (i.e., in the setting of extensive PC loss, even the heterotopias will be lost). Capitalizing on an ongoing prospective study of ET, we have assembled a large series of ET brains, as well as brains of patients with four forms of SCA and controls. Hence, we now revisit the issue of heterotopia in ET, (1) confirming whether it is present in ET and to what extent relative to controls, (2) asking how heterotopia is expressed in ET relative to other cerebellar degenerative conditions (SCA 1, 2, 3, and 6) (i.e., framing it within the larger context of degenerative conditions of the cerebellum), (3) asking how heterotopia is expressed in these SCAs relative to one another, and (4) assessing heterotopia within the context of associated PC loss in each disease.

Methods

Brain repository, study subjects, and neuropathological assessment

ET brains were from the Essential Tremor Centralized Brain Repository (ETCBR), a joint effort between investigators at Yale and Columbia Universities. All ET diagnoses were carefully assigned using three sequential methods, as described in detail [22]. Briefly, the clinical diagnosis of ET was initially assigned by treating neurologists, and then confirmed by an ETCBR study neurologist (EDL) using questionnaires, review of medical records and review of Archimedes spirals. Third, a detailed, videotaped, neurological examination was performed, and published diagnostic criteria applied, as described [22]. Total tremor scores (range = 0 – 36) were assigned based on the severity of postural and kinetic tremor (pouring, drinking, using spoon, drawing spirals, finger-nose-finger) on examination [38]. None of the ET cases had a history of traumatic brain injury, a history of exposure to medications known to cause cerebellar damage, or heavy ethanol use, as previously defined [22,39].

The majority of the control brains were obtained from the New York Brain Bank (NYBB) and were from individuals followed at the Alzheimer disease (AD) Research Center or the Washington Heights Inwood Columbia Aging Project at Columbia University [38]. They were followed prospectively with serial neurological examinations, and were clinically free of AD, ET, Parkinson’s disease (PD), Lewy body dementia, or progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). Nine control brains were from Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA) [38]. During life, all study subjects signed informed consent approved by these University Ethics Boards.

These analyses were designed initially to be performed on a sample of 100 brains comprising a 2:1 age-match of 46 ET cases to 23 controls with complete data, as well as all available SCA brains (n = 31, including 12 SCA1, 7 SCA2, 7 SCA3 and 5 SCA6). Tissue from these SCA brains was derived from several other brain repositories. We obtained 21 SCA cases from Dr. Arnulf Koeppen (Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Albany, New York), 8 SCA cases from the NIH NeuroBioBank (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD), 1 SCA case from Dr. José Luiz Pedroso (Ataxia Unit Federal University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil), and 1 SCA case from the NYBB. Three ET cases and one control had incomplete data; hence, the final sample size was 96. We performed a power analysis that utilized ET case and control data from our previous publication on heterotopic PCs [29], and used a 2:1 matching scheme (ET cases: controls). Assuming alpha = 0.05, then a sample of 30 ET cases and 15 controls would provide 80% power to detect a doubling of heterotopic PCs, as observed previously [29]; our study sample of 43 ET cases and 22 controls exceeded that. With the expectation that cerebellar pathology in SCA would be at least double that seen in ET, a sample size of 4 in each SCA group would provide 80% power. Our sample size exceeded that for each SCA group.

All ET and control brains had a complete neuropathological assessment at the NYBB and Harvard Brain Bank. Brains had standardized measurements of brain weight (grams). We did not include ET cases with Lewy body pathology (α-synuclein staining) [21] or PSP pathology [40].

Characterization of cerebellar pathology

A standard 3 × 20 × 25 mm parasagittal, formalin-fixed, tissue block was harvested from the neocerebellum; the block included the cerebellar cortex, white matter and dentate nucleus [22,26]. The block contained the anterior quadrangulate lobules in the anterior lobe of the cerebellar cortex, which are involved in motor control [41]. Using a single LH&E stained 7-μm thick section from this block, PCs were counted and averaged from 15 microscopic fields at 100× magnification (LH&E) [22,26,38]. The fields were selected as follows: (1) nonadjacent fields representing different regions of the section and (2) fields that were between, but not inclusive, of the base of the fissure and the apex of the folium [26]. We have previously shown that examination of a single, standard section provides an adequate representation of the pathology within that sample block. Using a systematic uniform random (SUR) sampling approach, one of every five sections obtained from a series of 40 collected paraffin sections from the standard cerebellar block was stained with LH&E. We determined that there was little variation in torpedo and PC counts among sampled sections within this block in 11 ET and 9 control brains. The agreement between these counts was very high (for torpedo counts, intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.96, p < 0.001; for PC counts, intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.94, p < 0.001).

As in prior postmortem studies [29–32], a heterotopic PC was identified as a PC whose cell body was completely surrounded by the molecular layer without contacting the granular layer. A trained technician (WJT), who was blinded to the clinical and diagnostic data, quantified heterotopic PCs throughout the entire standard LH&E stained section at 100× – 200× magnification. The counts of the trained technician agreed with those of the senior neuropathologist (PLF) (Pearson’s r = 0.93, p < 0.001 in 12 cases with counts ranging from 0 – 20). To standardize the heterotopic PC count (i.e., adjust for any variance in the length of the PC cell layer due to differences in tissue block size from case to case), we measured the length of the PC layer in each stained cortical section. The length of the PC layer (μm) was traced continuously along folia of the entire slide using an Olympus BX51 microscope under a FLUAR 2× (NA = 0.05) objective with the autocontour feature in StereoInvestigator software (11.01.2) (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT, USA). Each heterotopic PC count was normalized to PC layer length (μm) and then multiplied by 100 to obtain values that were in the range of 0 – 10 rather than 0.001 to 0.1; this value is referred to as n-heterotopias. The relative presence of PC loss is likely to impact the number of heterotopic PCs (i.e., in the setting of extensive PC loss, even the heterotopias will be lost); therefore, we also divided n-heterotopias by the PC count.

To confirm that heterotopic cells were PCs, we used immunohistochemistry to calbindinD28k protein. Seven μm paraffin-embedded cerebellar sections were rehydrated and incubated with 3 % hydrogen peroxide, treated with Trilogy solution (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA) in a conventional steamer for 40min, and blocked with 10 % normal donkey serum, 0.5 % bovine serum albumin, 1% Tween. The sections were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-calbindin-D28k (1:000, Swant, Marly) at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector labs, Burlingame, CA, 15 μg/ml), and the signals were amplified by avidin/biotinylated complex (Vector, Burlingame, CA). The sections were developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogen solution (Dako).

Statistical analyses

n-Heterotopia counts were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov p < 0.001); hence we used non-parametric tests to assess this variable. We assessed the correlates of n-heterotopia counts using Mann Whitney tests and Spearman’s correlation coefficients. We first compared clinical characteristics and brain weight across all 6 groups and then we compared each of the disease groups one by one to the controls (Table 1). For n-heterotopias and n-heterotopias/PC counts, which were our main measures, we compared all 6 groups initially and then each group to controls (Table 1). We also removed 4 data points that were outliers (identified as any data point that was at least 4 times higher than the value of the median of its group, 1 control, 1 ET case, 1 SCA3 and 1 SCA6) and compared the n-heterotopia/PC counts across groups. Data were analyzed in SPSS (v23).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Comparison of Study Groups

| Control | ET | SCA1 | SCA2 | SCA3 | SCA6 | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 22 | 43 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 5 | |

| Demographic Features | |||||||

| Age (years) | 83.5 ± 7.3 | 86.4 ± 6.7 | 62.1 ± 9.6 *** | 49.3 ± 14.8 *** | 54.2 ± 7.1 *** | 77.6 ± 6.2 | p < 0.001 a |

| Male Gender | 11 (50.0) | 16 (37.2) | 8 (66.7) | 5 (71.4) | 5 (83.3) | 3 (60.0) | p = 0.14 b |

| Postmortem Features | |||||||

| Brain Weight (grams) | 1186 ± 147 | 1205 ± 151 | 1190 ± 182 | 1029 ± 157 | 1355 ± 215 | 1242 ± 84 | p = 0.02 a |

| Purkinje cell counts | 10.3 ± 2.2 [11.0] | 8.1 ± 1.4 [8.3] *** | 5.3 ± 2.0 [4.1] *** | 2.7 ± 2.1 [2.4] *** | 11.3 ± 2.7 [10.7] | 3.0 ± 2.0 [2.3] *** | p < 0.001 c |

| n-Heterotopias | 2.7 ± 4.8 [1.2] | 3.2 ± 2.8 [2.6] ** | 3.2 ± 1.4 [3.1] ** | 2.7 ± 1.7 [2.2] | 10.7 ± 15.2 [4.5] ** | 2.5 ± 3.3 [1.8] | p = 0.12 c |

| n-Heterotopias/Purkinje cell count | 0.25 ± 0.37 [0.13] | 0.40 ± 0.33 [0.35] *** | 0.69 ± 0.40 [0.72] *** | 1.40 ± 0.97 [1.44] *** | 0.96 ± 1.38 [0.57] * | 0.64 ± 0.63 [0.39] | p < 0.001 c |

| n-Heterotopias/Purkinje cell count (no outliers) | 0.17 ± 0.16 [0.13] | 0.37 ± 0.28 [0.35] *** | 0.69 ± 0.40 [0.72] *** | 1.40 ± 0.97 [1.44] *** | 0.46 ± 0.43 [0.36] | 0.39 ± 0.33 [0.38] | p < 0.001 c |

Values represent mean ± standard deviation [median] or number (percentage).

PCs were counted and averaged from 15 microscopic fields at 100× magnification (LH&E). The fields were selected as follows: (1) nonadjacent fields representing different regions of the section and (2) fields that were between, but not inclusive, of the base of the fissure and the apex of the folium.

ANOVA comparing all 6 groups.

Chi-square test comparing all 6 groups.

Kruskall-Wallis test comparing all 6 groups.

p < 0.10 when compared to controls in Tukey’s post hoc comparison or in Mann-Whitney test.

p < 0.05 when compared to controls in Tukey’s post hoc comparison or in Mann-Whitney test.

p < 0.01 when compared to controls in Tukey’s post hoc comparison or in Mann-Whitney test.

Results

The ET cases and controls were similar in age at death, although SCA1, SCA2 and SCA3 cases were younger than controls (Table 1). Overall, gender did not differ significantly across the groups (p = 0.14, Table 1), nor did it differ between each individual case group and controls. The groups differed slightly by brain weight (p = 0.02), with that effect being driven by the difference between SCA2 and SCA3 (Tukey’s post hoc comparison p = 0.007) rather than a difference between any of the other case groups and controls.

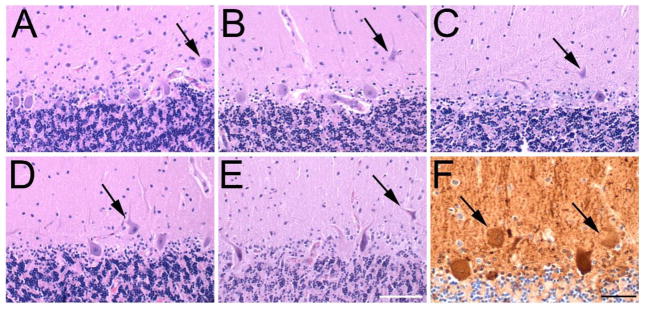

Heterotopic PCs were identified in the molecular layer, being completely surrounded by the molecular layer without contacting the granular layer (Figure 1A–E). Confirmation that heterotopic cells were PCs was determined by immunohistochemistry to calbindinD28k protein (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Heterotopic PCs.

Heterotopic PC bodies (black arrows) are located in the molecular layer, as shown in Control (A), ET (B), SCA2 (C), SCA3 (D) and SCA6 (E) cases. LH&E stained cerebellar cortical sections; scale bar (in E), 100 microns. Immunostain to calbindinD28k (F) in an ET case labels the heterotopic cells (black arrows), confirming that they are PCs. Scale bar, 50 microns.

The n-heterotopia counts were not correlated with age (Spearman r = −0.06, p = 0.59) or brain weight (Spearman r = −0.07, p = 0.50). The n-heterotopia counts were similar in men and women (Mann Whitney p = 0.32).

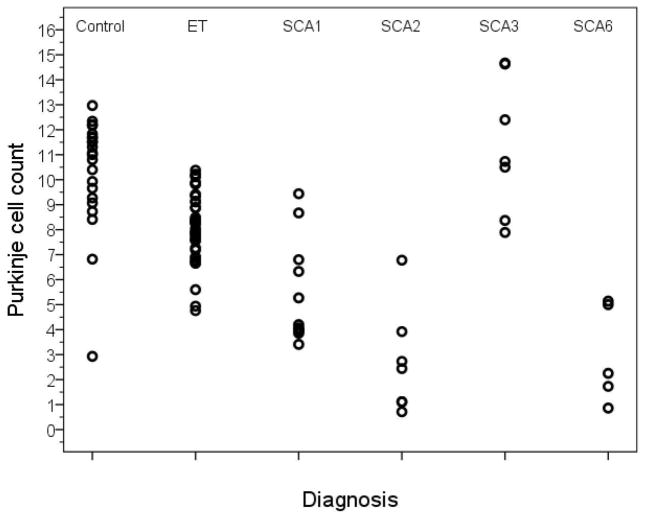

All groups, except SCA3, had lower PC counts than controls (Table 1, Figure 2). In addition, there was extensive overlap in data points across diagnoses; thus, the range of PC counts in ET, SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, and SCA6 overlapped that of controls (i.e., there were individuals with ET and each type of SCA whose PC count fell within the normal range), although PC loss was typically most severe in the SCA2 and SCA6 cases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Purkinje cell count by diagnosis.

PC count was determined in a single 7 μm thick LH&E stained cerebellar section as described in the Methods section. Counts were significantly lower versus controls in ET, SCA1, SCA2 and SCA6 and similar to controls in SCA3, although considerable overlap was seen between these diagnostic groups.

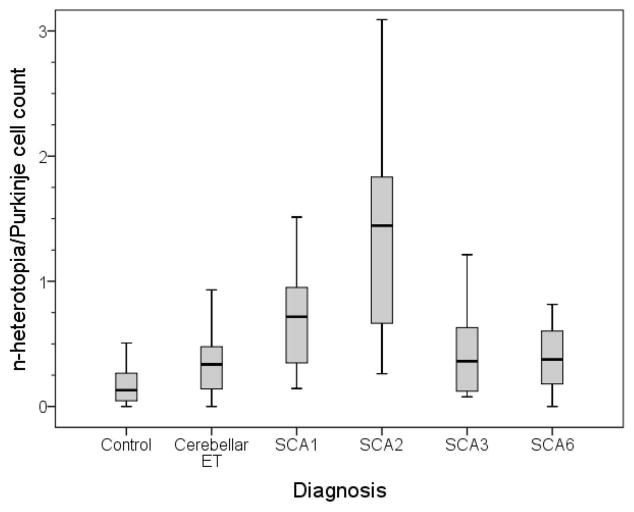

The median number of n-heterotopias in ET cases was two times higher than that of controls (2.6 vs. 1.2, p <0.05, Table 1). The number of n-heterotopias in the various SCAs formed a spectrum, with counts being highest in SCA3 and SCA1 (Table 1). We also divided n-heterotopias by PC counts; in these analyses, ET had a median n-heterotopia/PC count that was 3 times higher than controls (0.35 vs. 0.13, p < 0.01), with SCA1 and SCA2 having counts that were 5.5 and 11 times higher than controls (0.72 and 1.44 vs. 0.13, both p < 0.01, Table 1). The median values for n-heterotopia/PC count in SCA3 (0.57) and SCA6 (0.39) was higher than that in controls (0.13) but did not reach statistical significance, although the SCA sample size was small (Table 1).

In a secondary analysis, we also removed 4 data points that were outliers (1 control, 1 ET case, 1 SCA3 and 1 SCA6) and results (i.e., comparing n-heterotopia/PC counts) were similar (Table 1, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Median n-heterotopia/Purkinje cell count by diagnosis (outliers removed). Displayed are the median, interquartile range and distribution of outliers.

Discussion

In this paper, we confirm that ET cases have significantly more heterotopic PCs than controls. The median number in ET cases, when normalized for PC layer length, was two times higher than that of controls and, when further taking PC count into consideration, was three times higher than that of controls.

We also asked how heterotopia is expressed in ET relative to other cerebellar degenerative conditions (i.e., framing it within the larger context of degenerative conditions of the cerebellum). The number of heterotopias in the various SCAs formed a spectrum. SCA3 cases had the largest increase in n-heterotopia versus controls (4 times higher); in SCA3 the PC population is preserved and the brunt of cerebellar damage is in the dentate nucleus [42]. However, in analyses that considered the numbers of PCs, the n-heterotopia/PC count in SCA1 and SCA2 were 5.5 and 11 times higher than controls, whereas these values were not as high in SCA3 and SCA6. The relatively preserved PC population in SCA3 leads to a lower n-heterotopia/PC count [42,43]. The number of PC heterotopia in various forms of SCA has not been systematically studied, and is limited by small sample sizes in these rarely obtained human postmortem specimens. Future studies to include wider sampling of different cerebellar regions in control, ET and SCA cases may also be revealing.

The median n-heterotopia/PC count in ET (0.35) was between that of the controls (0.13) and the SCAs (0.39 in SCA6, 0.57 in SCA3, 0.72 in SCA1, and 1.44 in SCA2). Similarly, the median PC count in ET (8.3) was between that of the controls (11.0) and the SCAs (4.1 in SCA1, 2.4 in SCA2, and 2.3 in SCA6); the one exception was SCA3, in which the PC population is well-known to be preserved. Hence, in these regards, ET could represent an intermediate state or a less advanced state of spinocerebellar atrophy.

The mechanisms that underlie PC heterotopia in the setting of neurodegeneration are not fully understood. The cerebellar molecular layer contains PC dendrites, climbing fibers originating in the inferior olive, parallel fibers from granule cells, interneurons, Bergmann glia and microglia. Each of these neuronal and glial structures is dynamically regulated. Climbing fibers change innervation patterns dramatically in response to PC loss [44]. Parallel fibers and PC dendrites may also regress during neurodegeneration. Astrocytes and microglia undergo morphological and functional changes during neurodegenerative processes and contribute to non-autonomous neuronal death. These changes can result in the remodeling of cerebellar structures, leading to an untethering of PCs and a defective PC body localization [29].

Limitations of the study included the sample size. Although we were dealing with a sample of nearly 100 brains, for some diagnoses, the number of available brains was small. Nonetheless, given the magnitude of expected differences, our sample size calculations indicated that the number of brains provided would be sufficient to address our aims. Another limitation is that the age of onset of SCAs is often younger than that of ET. While ET cases and controls were similar at age of death, nearly all the SCA subgroups had a younger age at death. Nonetheless, we showed that n-heterotopia counts were not correlated with age; hence, age could not have confounded our main finding. Another limitation of the study was that we restricted our sampling to one region in the cerebellar hemisphere, and it would be of considerable interest in future studies to sample additional cerebellar regions. The strengths of the study include (1) the large number of ET brains, (2) the ability to compare ET to multiple types of SCA, including those in which PC loss is a feature and others in which it is not, (3) the uniqueness of the question (i.e., one prior study, our own, assessed heterotopias in ET cases vs. controls), (4) assessing heterotopias in relation to PC count.

In summary, heterotopia is a disease-associated feature of ET. In comparison, several of the SCAs evidenced even more marked heterotopia, although a spectrum existed across the SCAs. It is important to consider PC counts when assessing heterotopia, as loss of PCs extends both to normally located as well as heterotopic PCs.

Acknowledgments

Nine control brains were from Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA). Dr. Arnulf H. Koeppen, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Albany, New York, USA provided human SCA1, SCA2 and SCA6 tissue. Human SCA2 and SCA3 tissue was also obtained from the NIH NeuroBioBank at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD. An SCA3 human tissue specimen as also obtained from Dr. José Luiz Pedroso, Ataxia Unit Federal University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Dr. Louis has received research support from the National Institutes of Health: NINDS #R01 NS094607 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS39422 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS046436 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS073872 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS085136 (principal investigator) and NINDS #R01 NS088257 (principal investigator). He has also received support from the Claire O’Neil Essential Tremor Research Fund (Yale University). Dr. Kuo has received funding from the National Institutes of Health: NINDS #K08 NS083738 (principal investigator), and the Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Scholar Award, Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, and International Essential Tremor Foundation. Dr. Vonsattel has received funding from the National Institutes of Health: NINDS #R01 NS088257 (coinvestigator) and NINDS #R01 NS046436 (coinvestigator). Dr. Faust has received funding from the National Institutes of Health: NINDS #R01 NS088257 (principal investigator) and NINDS #R01 NS085136 (principal investigator).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest or competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Louis ED, Ferreira JJ. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2010;25:534–41. doi: 10.1002/mds.22838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dogu O, Sevim S, Camdeviren H, Sasmaz T, Bugdayci R, Aral M, et al. Prevalence of essential tremor: door-to-door neurologic exams in Mersin Province, Turkey. Neurology. 2003;61:1804–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000099075.19951.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benito-Leon J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Morales JM, Vega S, Molina JA. Prevalence of essential tremor in three elderly populations of central Spain. Mov Disord. 2003;18:389–94. doi: 10.1002/mds.10376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louis ED. The primary type of tremor in essential tremor is kinetic rather than postural: cross-sectional observation of tremor phenomenology in 369 cases. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20:725–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03855.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louis ED, Frucht SJ, Rios E. Intention tremor in essential tremor: Prevalence and association with disease duration. Mov Disord. 2009;24:626–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.22370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koster B, Deuschl G, Lauk M, Timmer J, Guschlbauer B, Lucking CH. Essential tremor and cerebellar dysfunction: abnormal ballistic movements. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:400–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.4.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer C, Sanchez-Ramos J, Weiner WJ. Gait abnormality in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 1994;9:193–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoskovcova M, Ulmanova O, Sprdlik O, Sieger T, Novakova J, Jech R, et al. Disorders of Balance and Gait in Essential Tremor Are Associated with Midline Tremor and Age. Cerebellum. 2012;12:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s12311-012-0384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Louis ED, Galecki M, Rao AK. Four Essential Tremor Cases with Moderately Impaired Gait: How Impaired can Gait be in this Disease? Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2013:3. doi: 10.7916/D8QV3K7G. pii: tre-03-200-4597-1. eCollection 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stolze H, Petersen G, Raethjen J, Wenzelburger R, Deuschl G. The gait disorder of advanced essential tremor. Brain. 2001;124:2278–86. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.11.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmchen C, Hagenow A, Miesner J, Sprenger A, Rambold H, Wenzelburger R, et al. Eye movement abnormalities in essential tremor may indicate cerebellar dysfunction. Brain. 2003;126:1319–32. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gitchel GT, Wetzel PA, Baron MS. Slowed saccades and increased square wave jerks in essential tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2013:3. doi: 10.7916/D8251GXN. pii: tre-03-178-4116-2. eCollection 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bares M, Lungu OV, Husarova I, Gescheidt T. Predictive motor timing performance dissociates between early diseases of the cerebellum and Parkinson’s disease. Cerebellum. 2010;9:124–35. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benito-Leon J, Labiano-Fontcuberta A. Linking Essential Tremor to the Cerebellum: Clinical Evidence. Cerebellum. 2016;15:253–62. doi: 10.1007/s12311-015-0741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerasa A, Quattrone A. Linking Essential Tremor to the Cerebellum-Neuroimaging Evidence. Cerebellum. 2016;15:263–75. doi: 10.1007/s12311-015-0739-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passamonti L, Cerasa A, Quattrone A. Neuroimaging of Essential Tremor: What is the Evidence for Cerebellar Involvement? Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2012:2. doi: 10.7916/D8F76B8G. pii: 02-67-421-3. Epub 2012 Sep 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louis ED, Shungu DC, Chan S, Mao X, Jurewicz EC, Watner D. Metabolic abnormality in the cerebellum in patients with essential tremor: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging study. Neurosci Lett. 2002;333:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00966-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharifi S, Nederveen AJ, Booij J, van Rootselaar AF. Neuroimaging essentials in essential tremor: a systematic review. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;5:217–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quattrone A, Cerasa A, Messina D, Nicoletti G, Hagberg GE, Lemieux L, et al. Essential head tremor is associated with cerebellar vermis atrophy: a volumetric and voxel-based morphometry MR imaging study. Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1692–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louis ED. Linking Essential Tremor to the Cerebellum: Neuropathological Evidence. Cerebellum. 2016;15:235–42. doi: 10.1007/s12311-015-0692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louis ED, Faust PL, Vonsattel JP, Honig LS, Rajput A, Robinson CA, et al. Neuropathological changes in essential tremor: 33 cases compared with 21 controls. Brain. 2007;130:3297–307. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babij R, Lee M, Cortes E, Vonsattel JP, Faust PL, Louis ED. Purkinje cell axonal anatomy: quantifying morphometric changes in essential tremor versus control brains. Brain. 2013;136:3051–61. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erickson-Davis CR, Faust PL, Vonsattel JP, Gupta S, Honig LS, Louis ED. “Hairy baskets” associated with degenerative Purkinje cell changes in essential tremor. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:262–71. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181d1ad04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo SH, Tang G, Louis ED, Ma K, Babji R, Balatbat M, et al. Lingo-1 expression is increased in essential tremor cerebellum and is present in the basket cell pinceau. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:879–89. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1108-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Louis ED, Babij R, Lee M, Cortes E, Vonsattel JP. Quantification of cerebellar hemispheric purkinje cell linear density: 32 ET cases versus 16 controls. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1854–9. doi: 10.1002/mds.25629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choe M, Cortes E, Vonsattel JG, Kuo SH, Faust PL, Louis ED. Purkinje cell loss in essential tremor: Random sampling quantification and nearest neighbor analysis. Mov Disord. 2016;31:393–401. doi: 10.1002/mds.26490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Symanski C, Shill HA, Dugger B, Hentz JG, Adler CH, Jacobson SA, et al. Essential tremor is not associated with cerebellar Purkinje cell loss. Mov Disord. 2014;29:496–500. doi: 10.1002/mds.25845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajput AH, Robinson CA, Rajput ML, Robinson SL, Rajput A. Essential tremor is not dependent upon cerebellar Purkinje cell loss. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:626–8. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo SH, Erickson-Davis C, Gillman A, Faust PL, Vonsattel JP, Louis ED. Increased number of heterotopic Purkinje cells in essential tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:1038–40. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.213330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura R, Kurita K, Kawanami T, Kato T. An immunohistochemical study of Purkinje cells in a case of hereditary cerebellar cortical atrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 1999;97:196–200. doi: 10.1007/s004010050974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomez CM, Thompson RM, Gammack JT, Perlman SL, Dobyns WB, Truwit CL, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6: gaze-evoked and vertical nystagmus, Purkinje cell degeneration, and variable age of onset. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:933–50. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamada M, Sato T, Tsuji S, Takahashi H. CAG repeat disorder models and human neuropathology: similarities and differences. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:71–86. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mangaru Z, Salem E, Sherman M, Van Dine SE, Bhambri A, Brumberg JC, et al. Neuronal migration defect of the developing cerebellar vermis in substrains of C57BL/6 mice: cytoarchitecture and prevalence of molecular layer heterotopia. Dev Neurosci. 2013;35:28–39. doi: 10.1159/000346368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bottini AR, Gatti RA, Wirenfeldt M, Vinters HV. Heterotopic Purkinje cells in ataxia-telangiectasia. Neuropathology. 2012;32:23–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2011.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahbazian MD, Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Reduction of Purkinje cell pathology in SCA1 transgenic mice by p53 deletion. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:974–81. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Q, Hashizume Y, Yoshida M, Wang Y, Goto Y, Mitsuma N, et al. Morphological Purkinje cell changes in spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100:371–6. doi: 10.1007/s004010000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goffinet AM, So KF, Yamamoto M, Edwards M, Caviness VS., Jr Architectonic and hodological organization of the cerebellum in reeler mutant mice. Brain Res. 1984;318:263–76. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuo SH, Wang J, Tate WJ, Pan MK, Kelly GC, Gutierrez J, et al. Cerebellar Pathology in Early Onset and Late Onset Essential Tremor. Cerebellum. 2017;16:473–82. doi: 10.1007/s12311-016-0826-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harasymiw JW, Bean P. Identification of heavy drinkers by using the early detection of alcohol consumption score. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:228–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Louis ED, Babij R, Ma K, Cortes E, Vonsattel JP. Essential tremor followed by progressive supranuclear palsy: postmortem reports of 11 patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:8–17. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31827ae56e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD. Functional topography in the human cerebellum: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage. 2009;44:489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koeppen AH, Ramirez RL, Bjork ST, Bauer P, Feustel PJ. The reciprocal cerebellar circuitry in human hereditary ataxia. Cerebellum. 2013;12:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s12311-013-0456-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rub U, Schols L, Paulson H, Auburger G, Kermer P, Jen JC, et al. Clinical features, neurogenetics and neuropathology of the polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2, 3, 6 and 7. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;104:38–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin CY, Louis ED, Faust PL, Koeppen AH, Vonsattel JP, Kuo SH. Abnormal climbing fibre-Purkinje cell synaptic connections in the essential tremor cerebellum. Brain. 2014;137:3149–59. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]