Abstract

Babesiosis is a zoonotic, tick-borne infection caused by the protozoan Babesia. It is transmitted by the Ixodes ticks which transmit the infection to humans. Babesia microti, Babesia duncani, Babesia divergens, and Babesia venatorum are species that have been identified as being infectious to humans worldwide. The most common species causing infection to humans is B. microti which is endemic to the Northeast and Midwestern United States with most infections occurring between the months of May and October. We report a case of an elderly man with acute liver failure due to an infection with B. microti.

Keywords: Babesiosis, Babesiosis acute liver failure, Acute liver failure, Infectious acute liver failure

Introduction

Infection with babesiosis starts with the bite of the deer tick, Ixodes scapularis. This tick transmits infections to humans. The natural reservoir of Babesia microti (BM), the species of Babesia most frequently found in the Northeastern and Midwestern United States (Fig. 1), is the white footed mouse [1, 2, 3]. The white tailed deer is not a reservoir but provides blood meals as a host for BM [4]. Transmission of BM from the I. scapularis tick typically requires 24–36 hours of tick attachment [5]. Transmission by blood transfusions, perinatal as well as transplacental transmission have been reported [1, 2]. Clinical signs and symptoms will typically begin showing 1–6 weeks after exposure to a tick bite [5]. Clinical manifestations are similar to those of malaria, with patients commonly presenting with a flu-like illness of fevers, chills, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting and fatigue [6].

Fig. 1.

CDC map of cases of babesiosis by state as of 2014. Image adapted from the CDC map of reported babesiosis cases.

The diagnosis of babesiosis can be made with a peripheral blood smear. Once the peripheral smear is obtained, the intraerythrocytic organism may be seen [6]. Serum PCR is a more sensitive method of diagnosing babesiosis and can detect infection despite a negative peripheral smear [7]. Treatment of infection with BM is based on the severity of the illness. In patients who are asymptomatic, current guidelines do not recommend treatment [8]. In patients with mild to moderate disease, treatment with 1 week of atovaquone and azithromycin are sufficient [8]. Severe infections of babesiosis are based on the parasite burden (estimated percentage of erythrocytes with intracellular organisms) or the underlying host status. Patient risk factors that increase the risk for severe disease include age greater than 50 years, splenectomy, malignancy, HIV infection, or immunosuppressive therapy [1]. Antimicrobial therapy that is reserved for those individuals with severe disease includes intravenous clindamycin as well as quinine [8]. Exchange transfusion is recommended for patients with severe parasitemia (>10%) as well as patients with severe anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dL) and organ failure related to babesiosis - pulmonary, liver, or renal impairment.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old male presented to our hospital with progressively worsening lethargy associated with worsening fatigue and weakness for several days prior to presentation. One day prior to presentation, his urine appeared bloody and he was brought to the hospital. He denied having any nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain but reported some intermittent fevers. He had a past medical history significant for ischemic cardiomyopathy with heart failure and he had atrial fibrillation for which he was taking Coumadin for anticoagulation. He lived in Upstate New York.

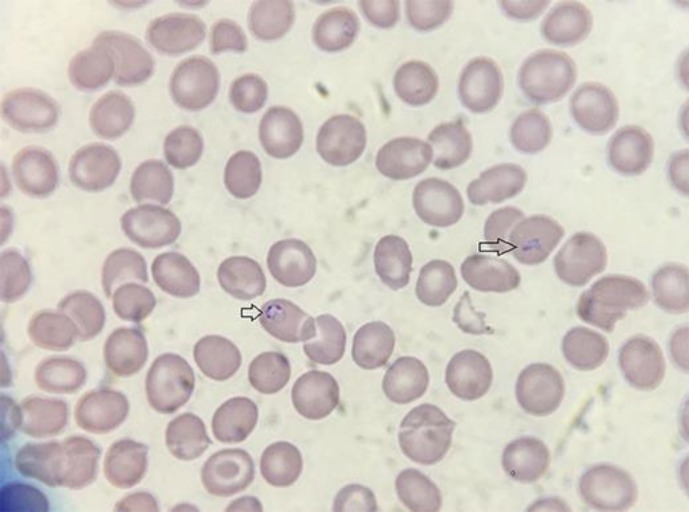

Initial vital signs were normal, and examination revealed hepatosplenomegaly as well as a petechial rash on his lower extremities. Initial lab results revealed a total bilirubin that was elevated at 2.8 mg/dL with an alkaline phosphatase of 159. AST was slightly elevated at 42 and ALT was at 51. INR (international normalized ratio) was initially 4.7 (patient was taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation) and albumin 3.2. Initial CBC showed a white blood count of 5.1, a hemoglobin count of 11.3 g/dL and a platelet count of 109,000. An abdominal ultrasound was requested which revealed ascites and a CBD diameter of 0.5 cm. While hospitalized, he was given multiple units of fresh frozen plasma as well as multiple doses of vitamin K to reverse the INR for possible ERCP, but it remained elevated greater than 3. During hospitalization, the patient had intermittent fevers, reaching as high as 103.2°F. Blood cultures were obtained that remained negative during the course of his hospitalization. His bilirubin continued to increase daily, reaching 15.1 g/dL 5 days later with a direct bilirubin fraction of 11.5 g/dL. Paracentesis was performed, which revealed an ascites albumin level of 1.2 g/dL and a serum albumin of 2.4 g/dL. Neutrophil count in the ascites fluid was 91 cells. Haptoglobin level was checked, which was low. The patient continued to develop worsening encephalopathy and continued to have fevers despite broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment with pipercillin-tazobactam for presumed ascending cholangitis and he subsequently became hypotensive. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit at which time a peripheral smear was obtained which can be seen in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Patient's peripheral smear depicting sporozoites of B. microti in erythrocytes. Wright-Giemsa stain. ×1,000.

Despite initiation of appropriate treatment with intravenous clindamycin and quinine, the patient's bilirubin continued to increase reaching a peak of 24 g/dL. Serum serology for Lyme, Erlichia as well as anaplasmosis were all negative. Unfortunately, the patient passed away prior to receiving exchange transfusion and an autopsy was not performed.

Discussion

We report the case of an elderly man with acute liver failure due to an infection with BM. In this case, the diagnosis remained unclear given the progressive elevation of bilirubin as well as the increase in aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase. It was suspected that the biliary tree was the underlying source of infection for the ongoing sepsis. Imaging studies were not suggestive of any biliary or intrahepatic causes of infection. Peripheral smear was diagnostic in this case by demonstrating the intraerythrocytic organisms seen on microscopy. The direct hyperbilirubinemia as well as persistently elevated INR and decrease in albumin were the result of fulminant liver failure which occurred as a complication of babesiosis.

Babesiosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute liver failure particularly in patients who are at risk of severe infection and end organ damage and are living in an endemic area or have recently travelled to an endemic area. Death rates in patients hospitalized with babesiosis can be as high as 1 in 10 [9, 10]. The relatively high mortality rate may be related to the underlying comorbidities in patients with babesiosis as well as the parasite burden. Misdiagnosis of babesiosis can lead to mismanagement and delay appropriate treatment for this infection, which can be fatal. Prompt treatment appropriately targeted based on severity can significantly reduce mortality rates of babesiosis. Assessing and appropriately treating those with severe infection and those who are at risk for severe infection is essential. The use of exchange transfusion in patients with significant disease burden and in those who have evidence of organ dysfunction can be a life-saving intervention.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Vannier EG, Diuk-Wasser MA, Ben Mamoun C, Krause PJ. Babesiosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:357–370. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vannier E, Krause PJ. Human babesiosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2397–2407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray J, Zintl A, Hildebrandt A, Hunfeld K-P, Weiss L. Zoonotic babesiosis: overview of the disease and novel aspects of pathogen identity. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2010;1:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vannier E, Krause PJ. Update on babesiosis. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2009;2009:984568. doi: 10.1155/2009/984568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kavanaugh MJ, Decker CF. Babesiosis. Dis Mon. 2012;58:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, John J, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1089–1134. doi: 10.1086/508667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kjemtrup AM, Conrad PA. Human babesiosis: an emerging tick-borne disease. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:1323–1337. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, Hu LT. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767–1777. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White DJ, Talarico J, Chang HG, et al. Human babesiosis in New York State: review of 139 hospitalized cases and analysis of prognostic factors. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2149–2154. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.19.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatcher JC, Greenberg PD, Antique J, et al. Severe babesiosis in Long Island: review of 34 cases and their complications. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1117–1112. doi: 10.1086/319742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]