Abstract

Objectives. To describe long-term national trends in health insurance coverage among US veterans from 2000 to 2016 in the context of recent health care reform.

Methods. We used 2000 to 2016 National Health Interview Survey data on veterans aged 18 to 64 years to examine trends in insurance coverage and uninsurance by year, income, and state Medicaid expansion status. We also explored the current proportions of veterans with each type of insurance by age group.

Results. The percentage of veterans with private insurance decreased from 70.8% in 2000 to 56.9% in 2011, whereas between 2000 and 2016 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care coverage (only) almost tripled, Medicaid (without concurrent TRICARE or private coverage) doubled, and TRICARE coverage of any type tripled. After 2011, the percentage of veterans who were uninsured decreased. In 2016, low-income veterans in Medicaid expansion states had double the Medicaid coverage (41.1%) of low-income veterans in nonexpansion states (20.1%).

Conclusions. Our estimates, which are nationally representative of noninstitutionalized veterans, show marked increases in military-related coverage through TRICARE and VA health care. In 2016, only 7.2% of veterans aged 18 to 64 years and 3.7% of all veterans (aged 18 years or older) remained uninsured.

The veteran population in the United States includes veterans of a variety of ages and active duty histories, including different combat, noncombat, and deployment experiences. The veteran population is also acknowledged to have a range of both unique and complex health care needs.1–3

To meet the needs of veterans, both TRICARE health plans (managed by the Defense Health Agency under the leadership of the assistant secretary of defense) and the Veterans Health Administration (operating under the Department of Veteran Affairs) have notably restructured and expanded in recent years.4–7 These changes have been co-occurring with broader legislative changes such as the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 (Pub L No. 111-148). There is renewed interest in veterans’ health care coverage and access to health care services in the context of national health care reform.8–12 However, long-term national trends in health insurance coverage among veterans are not well characterized, and it is not known whether they mirror published trends in the general population given that many veterans have additional options for health care coverage (i.e., TRICARE and Department of Veterans Affairs [VA] health care) outside of private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, and other government programs.

TRICARE health plans are available to veterans who are retired military personnel, qualified Selected Reserve members (US military reserve members most readily available for active service), or Medal of Honor recipients (or the dependents of veterans falling in 1 of these 3 categories), as well as the dependents of active-duty uniformed service members.13 These health plans in many ways function in a manner similar to private insurance, and they also meet the minimum essential coverage under the ACA. TRICARE programs (based on the prior Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services) were enacted into law by Congress in 1994.5 TRICARE introduced “TRICARE for Life” benefits in 2001 (for those eligible for Medicare) and “TRICARE Reserve Select” benefits in 2005 (for qualified Selected Reserve members and their families).5

The Veterans Health Administration is now the largest integrated health care system in the United States,14 with approximately 8.7 million veterans enrolled, 6 million of whom used the VA health care system in fiscal year 2016.15 VA health care is not considered by the Veterans Health Administration to be a health insurance plan,16 and not all veterans are eligible for VA health care. Basic eligibility requires that veterans be separated from active military service under any condition other than dishonorable. Enrollment is also prioritized on the basis of a number of factors such as income, disability status, and periods of service. Once enrolled, however, a veteran can have access for life, albeit with varying annual copayment requirements dependent largely on the prior year’s income.

Some veterans choose to use VA health care as their sole source of coverage (meeting minimum essential coverage under the ACA); however, others use it in addition to other coverage. Recent legislative changes have affected a veteran’s eligibility to enroll in VA health care and ease of access, including the National Defense Authorization Act of 2007 (Pub L No. 109-364), which extended automatic eligibility for enrollment in VA health care from 2 to 5 years after deployment, and the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 (Pub L No. 113-146), which introduced new service options for veterans with long waits or living long distances from VA facilities.6,7

In the case of veterans not eligible for a TRICARE health plan or VA health care, the other main coverage options include private insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare. Examples of national health care reform affecting veterans include the following: the ACA’s extension of dependent coverage (since 2011) enabling young veterans (aged 18–26 years) to remain on their parents’ insurance, the opening of health insurance exchanges in 2013 (for 2014 enrollment), the individual mandate requiring minimum essential coverage or payment of a penalty (effective in 2014), subsidies (on a sliding scale) for buying health insurance in 2014, and expanded access to Medicaid for veterans with low and moderate incomes in states that chose to expand Medicaid under the provisions of the ACA starting in 2014.

There is a lack of nationally representative data, particularly trend data, on the proportions of veterans covered by the various types of health insurance.17,18 Our aim, using data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), was to report long-term national trends in various types of health insurance coverage among US veterans aged 18 to 64 years from 2000 to 2016. We also examined trends in uninsurance by age group and recent changes (between 2010 and 2016) in insurance type by income and state Medicaid expansion status. In addition, we describe the current proportions of all veterans (aged 18 years or older in 2016) with each type of insurance by age group.

Given that veterans have unique health needs and 2 potential additional sources of coverage (TRICARE and VA health care) not open to the majority of civilians, and given that there have been health care legislation and reforms tailored to military personnel and veterans, it is unknown whether trends in insurance coverage among veterans from 2000 to 2016 will mirror or differ from those routinely observed in the general US population.

METHODS

We used data on US veterans from the NHIS, a multistage, nationally representative household survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the United States conducted continuously by the National Center for Health Statistics. In-person interviews are conducted in respondents’ homes, with occasional telephone follow-ups. In our study, we used the Family Core component of the survey, which includes information on veterans’ status and detailed data on health care coverage for all family members.

In total, 107 687 veterans were surveyed from 2000 to 2016. Veterans were defined as adults (aged 18 years or older) not currently on full-time active duty with the US Armed Forces who had ever been honorably discharged from active duty in the Armed Forces (2000–2010 questionnaires) or had ever served on active duty in the Armed Forces, military reserves, or National Guard (2011–2016 questionnaires). It should be noted that this change in measurement of veterans’ status in the NHIS means that some veterans in the samples from 2011 onward are not eligible for VA health care because they were dishonorably discharged. The NHIS does not sample homeless individuals or those residing in institutional settings, so veterans in these living situations were not included in the data. Our analytical sample was generally restricted to veterans aged 18 to 64 years (sample size = 62 192 veterans) with the exception of the data in Table 1 (insurance types by age group in 2016).

TABLE 1—

Numbers and Crude Percentages of Military Veterans Aged 18 Years or Older With Each Type of Health Insurance and Without Health Insurance, by Age Group: United States, 2016

| Age Group, Years, % (SE) |

Veterans Aged 18–64 Years |

Total Aged ≥ 18 Years, |

||||||||

| Insurance Type | 18–25 | 26–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | Weighted No. | % (SE) | Veterans Aged ≥ 65 Years, % (SE) | Weighted No. | % (SE) |

| Totala | 1.9 (0.2) | 7.1 (0.4) | 9.0 (0.4) | 15.5 (0.5) | 16.6 (0.5) | 10 364 790 | 50.0 (0.0) | 50.0 (0.8) | 20 731 014 | 100.0 (0.0) |

| Any TRICARE | 22.1 (5.0) | 13.2 (1.9) | 11.2 (1.4) | 13.7 (1.6) | 14.5 (1.5) | 1 404 322 | 13.8 (0.9) | 10.6 (0.7) | 2 498 506 | 12.2 (0.6) |

| Private (no TRICARE) | 41.1 (5.8) | 50.7 (3.2) | 65.6 (2.3) | 64.8 (2.3) | 54.4 (1.9) | 5 991 260 | 58.7 (1.1) | 46.8 (1.1) | 10 809 702 | 52.7 (0.8) |

| Medicaid (no TRICARE or private) | 10.7b (3.6) | 5.8 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.1) | 6.1 (1.1) | 7.1 (0.9) | 650 826 | 6.4 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.3) | 890 617 | 4.3 (0.3) |

| Other | . . .c | . . .c | 1.4b (0.5) | 2.7 (0.6) | 8.0 (1.0) | 395 872 | 3.9 (0.4) | 38.0 (1.1) | 4 306 215 | 21.0 (0.7) |

| VA health care (only) | 16.3b (6.1) | 15.7 (2.3) | 8.4 (1.5) | 6.7 (1.5) | 11.3 (1.2) | 1 034 418 | 10.1 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.3) | 1 247 288 | 6.1 (0.4) |

| Uninsured | 9.5b (3.2) | 13.7 (2.1) | 8.3 (1.4) | 6.0 (1.4) | 4.7 (0.7) | 734 791 | 7.2 (0.6) | . . .c | 747 931 | 3.7 (0.3) |

Note. VA = Department of Veterans Affairs. Data were derived from the 2000–2016 versions of the National Health Interview Survey. Health insurance is coverage at the time of the interview.

For total veterans (aged ≥ 18 years), percentages are row percentages.

Relative standard error > 30% or ≤ 50%; should be interpreted with caution.

Relative standard error > 50%.

In our analyses, a hierarchical variable—type of health insurance—was used as the primary dependent variable; this variable had the following ordered categories: any TRICARE, private, Medicaid, other health insurance sources, VA health care only, and uninsured. These categories were mutually exclusive, and veterans with multiple types of coverage were categorized into the first applicable category. For example, a veteran with both TRICARE and private insurance was categorized into the TRICARE category.

TRICARE coverage includes any TRICARE plan. Private coverage includes comprehensive private insurance plans such as those obtained through an employer, purchased directly, purchased through local or community programs, or purchased through the health insurance marketplace or state-based exchanges. Medicaid coverage includes Medicaid and state-sponsored plans. Other sources include Medicare, the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and other government coverage. The VA health care only category captured respondents who reported VA health care but no other coverage type. Uninsured individuals were those without any TRICARE, private, Medicaid, VA health care, or other coverage or who had only Indian Health Service coverage or single-service plans (e.g., vision, dental).

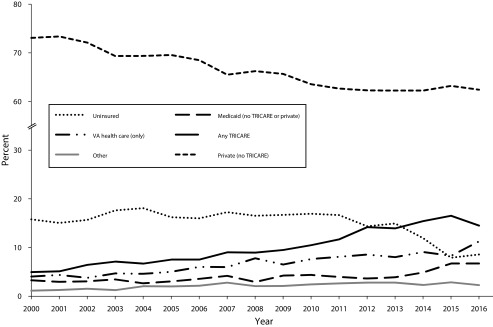

To account for changes in the age distribution of the veteran population from 2000 to 2016, we age adjusted the estimates of long-term trends shown in Figure 1 (and Appendixes A and D, available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) by using the projected 2000 US population as the standard population and including 5 age groups: 18 to 25 years, 26 to 34 years, 35 to 44 years, 45 to 54 years, and 55 to 64 years.19

FIGURE 1—

Age-Adjusted Percentages of Military Veterans Aged 18–64 Years With Each Type of Health Insurance and Without Health Insurance, by Year: United States, 2000–2016

Note. VA = Department of Veterans Affairs. Data were derived from the 2000–2016 versions of the National Health Interview Survey. Health insurance is coverage at the time of the interview. Figures reflect point estimates for the indicated year. Estimates are age adjusted with the projected 2000 US population as the standard population and with 6 age groups (18–25, 26–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 years).

All percentages and standard errors were calculated with SUDAAN to account for the complex survey design, and NHIS sample weights were used to produce estimates nationally representative of the noninstitutionalized population of veterans residing in the United States.20 We used Joinpoint software to assess the statistical significance of trends in health care coverage.21 Joinpoint regression incorporates statistical criteria to determine the smallest number of joined linear segments necessary to characterize a trend, the year when a segment begins and ends, and the annual percentage change for each trend segment. A 95% confidence interval around the annual percentage change is used to determine whether the annual change for each segment is significantly different from zero (and, thereby, whether the trend is increasing, decreasing, or constant). We used weighted least squares regression, with each weight defined as the square of the response variable divided by the square of the standard error.

RESULTS

In 2016, there were approximately 21 million veterans in the United States, of whom 50% were aged 18 to 64 years. Among veterans in that age group, approximately 13.8% had any type of TRICARE, 58.7% had private insurance (and not TRICARE), 6.4% had Medicaid coverage (and not TRICARE or private coverage), 3.9% had coverage from other sources only, 10.1% had VA health care only, and 7.2% were uninsured (Table 1). Among veterans aged 65 years or older, other coverage (predominantly Medicare) was more common (38.0%), and uninsurance was very rare (less than 0.5%). Young veterans in the 18- to 25-year and 26- to 34-year age groups were more likely than those in other age groups to be covered by VA health care only (16.3% and 15.7%, respectively) or to be uninsured (9.5% and 13.7%, respectively).

There was a decrease in the age-adjusted percentage of veterans aged 18 to 64 years with private insurance between 2000 and 2011, from 70.8% to 56.9% (P < .001); there was no significant change in the age-adjusted percentage with private insurance from 2012 to 2016 (Figure 1; see Appendix A for corresponding data with crude percentages included). Conversely, the age-adjusted percentage of veterans aged 18 to 64 years with any TRICARE increased steadily from 2000 to 2016 (from 5.0% to 14.5%; P < .001), as did the percentage with VA health care only (from 4.0% to 11.3%; P < .001).

Medicaid coverage increased slowly between 2000 and 2012, with an annual percentage change of 2.5% (rising from 3.3% to 3.6%; P = .03), followed by an escalated increase (annual percentage change of 21.5%) from 2013 to 2016 (rising from 3.9% to 6.7%; P < .05). The age-adjusted percentage of those with other coverage rose between 2000 and 2016 (from 1.1% to 2.3%; P < .001). The age-adjusted percentage of veterans who were uninsured did not change significantly from 2000 to 2010, after which it dropped by nearly a half, from 16.7% in 2011 to 8.6% in 2016 (P < .001).

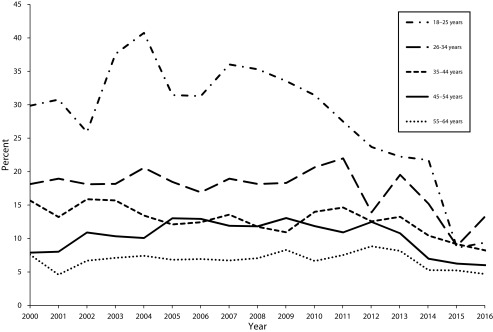

Uninsurance trends between 2000 and 2016 differed by age (Figure 2; see Appendix B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for a data table). Among the youngest veterans (those aged 18–25 years), the crude percentage who were uninsured fluctuated (but did not change significantly) from 2000 to 2008 before decreasing from 33.5% in 2009 to 9.4% in 2016 (P < .01). There was no significant change in uninsurance among veterans aged 26 to 34 years from 2000 to 2016. Among those aged 35 to 44 years, uninsurance decreased overall from 2000 to 2016 (from 15.7% to 8.2%; P < .01). Uninsurance increased among veterans aged 45 to 54 years between 2000 and 2004 (from 7.9% to 10.1%; P = .01), stabilized until 2011, and then decreased (from 12.5% in 2012 to 6.0% in 2016; P < .01). There have been no significant changes over the past 17 years in the percentages of veterans aged 55 to 64 years who are uninsured.

FIGURE 2—

Crude Percentages of Military Veterans Aged 18–64 Years Who Lack Health Care Coverage, by Age Group and Year: United States, 2000–2016

Note. Data were derived from the 2000–2016 versions of the National Health Interview Survey. Uninsured refers to lack of coverage at the time of the interview. Figures reflect point estimates for the indicated year.

The ACA’s expansion of Medicaid eligibility was not uniformly implemented across states. We examined changes in coverage between 2010 and 2016 among veterans aged 18 to 64 years by income and state Medicaid expansion status. TRICARE coverage increased among moderate-income veterans in both Medicaid expansion states (from 6.9% to 11.5%; P = .03) and nonexpansion states (from 9.4% to 15.3%; P = .02; Table 2; see Appendix C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for the corresponding figure). Among low- and moderate-income veterans, there was no significant change in the crude percentage with private insurance between 2010 and 2016, regardless of whether they lived in a Medicaid expansion state.

TABLE 2—

Crude Percentages of Military Veterans Aged 18–64 Years With Each Type of Health Insurance and Without Health Insurance, by Family Income, Medicaid Expansion Status, and Year: United States, 2010 and 2016

| Low Income (≤ 138% FPL), % (SE) |

Moderate Income (139%–400% FPL), % (SE) |

|||

| Insurance Type | 2010 | 2016 | 2010 | 2016 |

| Medicaid expansion states | ||||

| Uninsured | 29.2 (3.4) | 12.5 (2.8) | 15.3 (1.5) | 7.8 (1.3) |

| VA health care (only) | 14.8 (2.8) | 15.4 (3.0) | 12.8 (1.5) | 12.3 (1.6) |

| Other | 6.8a (2.2) | 9.6 (2.3) | 6.3 (1.0) | 5.5 (1.0) |

| Medicaid (no TRICARE or private) | 23.8 (3.4) | 41.1 (4.0) | 3.5 (0.8) | 4.7 (0.9) |

| Private (no TRICARE) | 23.2 (3.4) | 15.7 (2.6) | 55.2 (2.3) | 58.3 (2.4) |

| Any TRICARE | 2.3a (1.0) | 5.8a (2.1) | 6.9 (1.3) | 11.5 (1.6) |

| Non–Medicaid expansion states | ||||

| Uninsured | 33.0 (3.7) | 22.7 (3.7) | 14.0 (1.6) | 10.4 (1.5) |

| VA health care (only) | 23.2 (3.6) | 20.2 (3.3) | 14.1 (1.6) | 14.9 (2.0) |

| Other | 7.8 (2.1) | 8.2 (2.2) | 5.6 (1.0) | 5.8 (1.1) |

| Medicaid (no TRICARE or private) | 8.9 (2.1) | 20.1 (3.4) | 1.8a (0.7) | 3.7 (1.0) |

| Private (no TRICARE) | 20.6 (3.2) | 17.0 (3.2) | 55.2 (2.3) | 49.9 (2.4) |

| Any TRICARE | 6.4a (2.0) | 11.8 (2.7) | 9.4 (1.3) | 15.3 (2.1) |

Note. FPL = federal poverty level; VA = Department of Veterans Affairs. Data were derived from the 2000–2016 versions of the National Health Interview Survey. Health insurance is coverage at the time of the interview. Income refers to family income, which is the income of an individual or group of ≥ 2 related people living together in the same housing unit. Medicaid expansion states include states that had adopted Medicaid expansion for a majority of 2016 or earlier (AK, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, DC, HI, IL, IN, IA, KY, MD, MA, MI, MN, MT, NV, NH, NJ, NM, NY, ND, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV).

Relative standard error > 30% or ≤ 50%; should be interpreted with caution.

Medicaid coverage increased significantly among low-income veterans in both Medicaid expansion (from 23.8% to 41.1%) and nonexpansion (from 8.9% to 20.1%) states; however, the magnitude of the change was higher in Medicaid expansion states than in nonexpansion states (58.0% increase vs 44.4% increase). There was no change in the percentage of veterans with other or VA-only coverage in any category between 2010 and 2016.

Overall, in states that expanded Medicaid, uninsurance dropped significantly among both low-income (from 29.2% to 12.5%; P < .001) and moderate-income (from 15.3% to 7.8%; P < .001) veterans (Table 2; see Appendix C for the corresponding figure). However, in nonexpansion states, the drop in uninsurance observed among low- and moderate-income veterans was smaller and not statistically significant. In both 2010 and 2016, uninsurance was highest among low-income veterans from nonexpansion states (33.0% and 22.7%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

From 2000 to 2016, veterans’ health care coverage increasingly comprised TRICARE, Medicaid, or VA health care (only), with a decreasing proportion of veterans covered by private insurance. From 2011 onward, uninsurance among veterans aged 18 to 64 years declined, and in 2012 the percentage with private coverage stopped decreasing.

As noted by Cohen et al., the decrease in private coverage was also seen in the general population prior to 2013, albeit at a slower rate (with an approximate 0.8% decrease per year in the general population and a 2.0% decrease per year in the population of veterans aged 18 to 64 years).22 It should be noted that, in our analyses, veterans who jointly had private insurance and TRICARE coverage (1.8% of veterans aged 18 to 64 years; data not shown) were grouped into the TRICARE coverage category. Therefore, we conducted additional analyses of veterans with “any private insurance” (see Appendix D) to make sure that the trends in private insurance among veterans were being fairly compared with trends in the general population, which did not account for people with TRICARE coverage.

The data in Appendix D show the same trends in any private insurance that were observed in Figure 1 (private coverage, no TRICARE): there was a significant decrease in the age-adjusted percentage of veterans with any private insurance from 2000 to 2011 (P < .001), and there was no significant change in the percentage with any private insurance from 2012 to 2016.

From 1997 to 2007, Cohen et al. also reported a 5.4% increase per year in Medicaid coverage among US adults aged 18 to 64 years.23 A much slower rise in Medicaid coverage was observed in the veteran population (aged 18–64 years) from 2000 to 2012 (an increase of 2.5% per year). Although the NHIS data are cross sectional, and therefore casual inferences cannot be made, this slower increase in Medicaid might be explained by the accompanying increases in TRICARE and VA-only coverage observed in the veteran population over the same time period.

The increasing trend in the proportion of veterans aged 18 to 64 years who are covered by TRICARE could be due to the newly available TRICARE Reserve Select plan, which covers National Guard or reserve members (in deactivated status). After September 11, 2001, there was a surge in the number of National Guard members becoming activated (more than 50 000 by December 2001).24 Once these troops were deactivated, they were considered veterans, and after 2005 some were eligible for TRICARE Reserve Select.13 The TRICARE increases could also reflect underlying temporal changes in the veteran population since the end of the draft in the 1970s, with an increasing percentage of the veteran population consisting of professional soldiers who retired from the military (rather than being discharged) and who are therefore eligible for 5 of the existing TRICARE health plans.25

Of the 8.7 million enrollees in VA health care and the 6 million veterans who used the VA in 2016,15 estimates derived from the NHIS data suggest that 1.2 million (an estimated 14% of veterans enrolled in and 20% of veterans using VA health care in 2016) relied on VA health care alone for their health coverage. The increasing trend in the percentage of veterans citing the VA as their only source of coverage (from 4.0% in 2000 to 11.3% in 2016) is consistent with the increasing enrollment and use of VA health care reported by the VA.26

Historically, veterans have been much less likely than nonveterans to be uninsured.27 We found that, in 2000, 11.3% (crude percentage; see Appendix A) of veterans aged 18 to 64 years were uninsured, as compared with the published figure of 16.8% in the general population.23 The proportion of veterans without coverage began to decrease in 2011, and 2 years later (2013) a decrease was observed in the general population.22 The overall increasing trends in TRICARE and VA-only coverage among veterans might explain why the decrease in uninsurance was observed earlier among veterans than in the general population. As of 2016, the magnitude of the difference in uninsurance (5.2 percentage points) between veterans aged 18 to 64 years (7.2%) and the general population in that age group (12.4%) remained similar to the aforementioned difference in 2000 (5.5 percentage points).22

Veterans in the younger age groups had the highest levels of uninsurance. Among the youngest veterans (aged 18–25 years), uninsurance began to decrease significantly and continuously after 2009. This decrease roughly coincided with a pair of legislation-related changes: the National Defense Authorization Act of 2007, which extended automatic eligibility for enrollment in VA health care from 2 to 5 years after deployment, and the extension of dependent coverage, allowing young adults (aged 18–25 years) to remain insured through their parents for the first time under the ACA. Between 2009 and 2016, uninsurance among these youngest veterans decreased by 24.1 percentage points. It should be noted, however, that the proportion of veterans aged 26 to 34 years who are uninsured has not changed significantly since 2000, and uninsurance actually increased among veterans aged 45 to 54 years until 2005. In 2012, the percentage of veterans without coverage began to decrease among those aged 45 to 54 years, 1 year earlier than decreases in uninsurance in the general population.

In 2010, states that later chose to expand Medicaid coverage had a higher proportion of low- and moderate-income veterans aged 18 to 64 years who were covered by Medicaid (even after stratification by income group) than states that did not expand Medicaid. Even though low-income veterans had increased coverage through Medicaid by 2016, regardless of expansion status, the magnitude of the increase was higher in expansion states. Low-income veterans in expansion states had the highest Medicaid coverage of all groups (41.1%) in 2016, double the percentage of low-income veterans in nonexpansion states who were covered by Medicaid (22.7%). TRICARE coverage increased among moderate-income veterans regardless of their state’s expansion status, probably reflecting overall trends in the veteran population. However, the lack of significant changes in uninsurance among low- and moderate-income veterans in nonexpansion states (despite overall decreases in uninsurance among veterans after 2011) needs further investigation.

The observed trends between 2000 and 2016 may have been influenced by the previously mentioned change in the NHIS’s measurement of veteran status (and therefore the denominator) from 2011 onward. In 2011 and subsequently, veterans who were dishonorably discharged and therefore not eligible for VA health care were nevertheless included in the denominator, and there was a concurrent wording change clarifying but not changing the inclusion of veterans who had been in prior active duty with the reserves or the National Guard (and who therefore were potentially eligible for VA health care). However, the change in measurement of this denominator in 2011 did not significantly change the estimated population size. As calculated via the NHIS data, there was no significant change in the estimated veteran population size from 2008 to 2016 (the figure remained at approximately 21 million; data not shown). Therefore, it is unlikely that the change in measurement influenced the direction or overall significance of the observed trends in health insurance coverage.

The focus of this study was a descriptive analysis of trends over time, as opposed to a prepolicy–postpolicy analysis of the ACA. Although we were able to compare insurance coverage in the veteran population between 2010 and 2016 by state Medicaid expansion status, it was not within the scope of our study to assess and control for state-level legislation and other state-level factors (other than stratifying by income). Moreover, this descriptive analysis of trends does not lend itself to an examination of other aspects of health reform such as guaranteed coverage for preexisting conditions.

The NHIS data have many strengths. The NHIS has been collecting health insurance data periodically since 1959 and annually since 1989, allowing for long-term trend analyses. NHIS estimates of health insurance and coverage are more suited for the present analysis than are other survey-based estimates (such as the Current Population Survey) because the NHIS differentiates between sources of military-related health insurance (instead of combining them as 1 category).

The NHIS also makes use of responses to follow-up questions (including questions about specific plan names) to evaluate the reliability of reported health insurance coverage and adjudicate conflicting information when necessary. This detailed measurement allowed for the creation of a hierarchical variable categorizing important health insurance types among veterans while accounting for the fact that people (and veterans especially) can have multiple sources of coverage. This categorization of health insurance coverage among veterans and the subsequent data analyses complement VA administrative statistics on enrollment in and use of VA health care. Given that administrative data on outside sources of coverage (such as private insurance) are incomplete,17,18 the NHIS data add to the knowledge base of where veterans obtain health coverage beyond the VA.

In conclusion, the increasing trends in Medicaid coverage (possibility accelerated by Medicaid expansion) and decreasing trends in private insurance coverage among veterans aged 18 to 64 years mirror the trends seen in the general population from 2000 to 2016. However, veteran-specific gains in coverage have been observed, including an earlier decrease in uninsurance rates (particularly among young veterans) and marked increases in coverage through TRICARE health plans and VA health care. Uninsurance is now at an all-time low, with only 7.2% of veterans aged 18 to 64 years and 3.7% of all veterans (aged 18 years or older) lacking insurance coverage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the helpful input and advice of colleagues at the National Center for Health Statistics, in particular Stephen Blumberg, Jennifer Madans, Aaron Maitland, and Robin Cohen.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Data collection for the National Health Interview Survey was approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics. De-identified data were used in the current study.

Footnotes

See also Adler, p. 298.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Veterans’ use of VA mental health services and disability compensation increased from 2001 to 2010. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(6):966–973. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilmoth JM, London AS, Parker WM. Military service and men’s health trajectories in later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65(6):744–755. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.True G, Rigg KK, Butler A. Understanding barriers to mental health care for recent war veterans through photovoice. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(10):1443–1455. doi: 10.1177/1049732314562894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Extreme makeover: transformation of the veterans health care system. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:313–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell N. Briefing on the history of military retirees. Available at: http://www.vfw6872.org/History%20of%20Military%20Healthcare.htm. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- 6.Department of Veterans Affairs. Fact sheet: Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014. Available at: https://www.va.gov/opa/choiceact/documents/Choice-Act-Summary.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- 7. National Defense Authorization Act of 2007, Pub L No. 109–364.

- 8.Kizer KW. Veterans and the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2012;307(8):789–790. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chokshi DA, Sommers BD. Universal health coverage for US veterans: a goal within reach. Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2320–2321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61254-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haley JK, Kenney GM. Uninsured veterans and family members: state and national estimates of expanded Medicaid eligibility under the ACA. Available at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/uninsured-veterans-and-family-members-state-and-national-estimates-expanded-medicaid-eligibility-under-aca. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- 11.Haley J, Kenney G, Gates J. Health Reform—Monitoring and Impact. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haley J, Gates J. ACA Implementation—Monitoring and Tracking. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Defense. TRICARE eligibility. Available at: https://tricare.mil/Plans/Eligibility. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- 14.Veterans Health Administration. About VHA. Available at: http://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- 15.Veterans Health Administration. VHA Expenditures, Enrollees, and Patients, VHA Vital Stats: National Data, Fiscal Year 2016. Washington DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2016. Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Policy and Planning. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Veterans Affairs. Health benefits. Available at: https://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/cost/insurance.asp. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- 17.Smith ME, Sheldon G, Klein RE et al. Data and information requirements for determining veterans’ access to health care. Med Care. 1996;34(suppl 3):MS45–MS54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hynes DM, Koelling K, Stroupe K et al. Veterans’ access to and use of Medicare and Veterans Affairs health care. Med Care. 2007;45(3):214–223. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244657.90074.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein R, Schoenborn C. Age Adjustment Using the 2000 Projected US Population. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. SUDAAN [computer program], release 9.4. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2015.

- 21. Joinpoint regression software [computer program], version 4.2. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2015.

- 22.Cohen RA, Martinez ME, Zammitti EP. Health insurance coverage: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January–March 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201708.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- 23.Cohen RA, Makuc DM, Bernstein AB, Bilheimer LT, Powell-Griner E. Health Insurance Coverage Trends, 1959–2007: Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Guard. About the National Guard. Available at: http://www.nationalguard.mil/About-the-Guard/Army-National-Guard. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- 25.Segal MW, Segal DR. Implications for military families of changes in the armed forces of the United States. In: Caforio G, editor. Handbook of the Sociology of the Military. Boston, MA: Springer; 2006. pp. 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Trends in the utilization of VA programs and services. Available at: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/QuickFacts/Utilization_trends_2014.PDF. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- 27.Holder KA. Health Insurance Coverage, Poverty, and Income of Veterans: 2000 to 2009. Washington, DC: National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]