Abstract

Risk-taking behaviour is a key component of several psychiatric disorders and could influence lifestyle choices such as smoking, alcohol use, and diet. As a phenotype, risk-taking behaviour therefore fits within a Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) approach, whereby identifying genetic determinants of this trait has the potential to improve our understanding across different psychiatric disorders. Here we report a genome-wide association study in 116,255 UK Biobank participants who responded yes/no to the question “Would you consider yourself a risk taker?” Risk takers (compared with controls) were more likely to be men, smokers, and have a history of psychiatric disorder. Genetic loci associated with risk-taking behaviour were identified on chromosomes 3 (rs13084531) and 6 (rs9379971). The effects of both lead SNPs were comparable between men and women. The chromosome 3 locus highlights CADM2, previously implicated in cognitive and executive functions, but the chromosome 6 locus is challenging to interpret due to the complexity of the HLA region. Risk-taking behaviour shared significant genetic risk with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as with smoking and total obesity. Despite being based on only a single question, this study furthers our understanding of the biology of risk-taking behaviour, a trait that has a major impact on a range of common physical and mental health disorders.

Introduction

Risk-taking behaviour is an important aspect of several psychiatric disorders, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)1,2 and bipolar disorder (BD)3, as well as problem behaviours such as smoking and drug and alcohol misuse4,5. The link between risk-taking behaviour and schizophrenia (SCZ) is more complex, with difficulties in conditional reasoning6, problems with delayed gratification and poor impulse control occurring alongside more conservative risk assessment7. Physical health problems such as obesity might also be considered to be related to increased propensity towards risk taking: obesity includes aspects of aberrant reward processing, response inhibition, and decision making8. The Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) approach suggests that studying dimensional psychopathological traits (rather than discrete diagnostic categories), as well as relevant traits across the whole spectrum (“normal” through to pathological) of the population may be a more useful strategy for identifying biology, which cuts across psychiatric diagnoses9. In this respect, risk-taking behaviour is an important phenotype for investigation. It may also be useful for investigating the overlap between psychiatric disorders and conditions such as obesity and smoking.

To date, an association between a locus on chromosome 3 and risk-taking behaviour has been published10,11, but no genome-wide genetic study with a primary focus on risk-taking behaviour has been conducted. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of related phenotypes, such as impulsivity and behavioural disinhibition, have so far been underpowered for detecting associations at a genome-wide level. Here we conduct a primary GWAS of self-reported risk-taking behaviour in 116,255 participants from the UK Biobank cohort. We use expression quantitative trait loci analysis to highlight plausible candidate genes and we assess the extent to which there is a genetic correlation between risk-taking and several mental and physical health disorders, including ADHD, SCZ, BD, major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), smoking status (ever smoker), lifetime cannabis use, fluid intelligence, years of education, obesity, and alcohol use disorder.

Materials and methods

Sample

UK Biobank is a large population cohort, which aims to investigate a diverse range of factors influencing risk of diseases, which are common in middle and older age. Between 2006 and 2010, >502,000 participants (age range from 40 and 69 years) were recruited from 22 centres across the United Kingdom (UK)12. Comprehensive baseline assessments included social circumstances, cognitive abilities, lifestyle, and measures of physical health status. The present study used the first release of genetic data on approximately one-third of the UK Biobank cohort. In order to maximise homogeneity, we included only participants of (self-reported) white UK ancestry.

Informed consent was obtained by UK Biobank from all participants. This study was carried out under the generic approval from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (approval letter dated 13 May 2016, ref 16/NW/0274) and under UK Biobank approval for application #6553 “Genome-wide association studies of mental health” (PI Daniel Smith).

Genotyping, imputation, and quality control

The first release of genotypic data from UK Biobank, in June 2015, included 152,729 UK Biobank participants. Samples were genotyped with either the Affymetrix UK Biobank Axiom array (Santa Clara, CA, USA; approximately 67%) or the Affymetrix UK BiLEVE Axiom array (33%), which share at least 95% of content. Autosomal data only were available.

Imputation of the data has previously been described in the UK Biobank interim release documentation13. In brief, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were excluded prior to imputation if they were multiallelic or had minor allele frequency (MAF) <1%. A modified version of SHAPEIT2 was used for phasing and IMPUTE2 (implemented on a C++ platform) was used for the imputation14,15. A merged reference panel of 87,696,888 biallelic variants on 12,570 haplotypes constituted from the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 and UK10K haplotype panels16 was used as the basis for the imputation. Imputed variants with MAF < 0.001% were filtered out of the data set used for subsequent analysis.

The Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics applied stringent quality control, as described in UK Biobank documentation17, before release of the genotypic data set. UK Biobank genomic analysis exclusions were applied (Biobank Data Dictionary item #22010). Participants were excluded from analyses due to relatedness (#22012: genetic relatedness factor; one member of each set of individuals with KING-estimated kinship coefficient >0.0442 was removed at random), sex mismatch (reported compared with genetic) (#22001: genetic sex), non-Caucasian ancestry (#22006: ethnic grouping; self-reported and based on principal component (PC) analysis of genetic data), and quality control failure (#22050: UK BiLEVE Affymetrix quality control for samples and #22051: UK BiLEVE genotype quality control for samples). SNPs were removed due to deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium at p < 1 × 10−6, MAF < 0.01, imputation quality score <0.4 and >10% missingness in the sample after excluding genotype calls made with <90% posterior probability.

The second release of genetic data from the UK Biobank (July 2017) included a further 349,935 samples. Genotyping platforms, quality control, and pre-imputation procedures were consistent with the first data release. Imputation of genotypes at additional SNP loci for all participants (n = 502,664) was carried out using the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC) reference panel, and post-imputation quality control was consistent with that of the first data release.

Risk-taking phenotype

The baseline assessment (2006–2010) of UK Biobank participants included the question “Would you describe yourself as someone who takes risks?” (data field #2040), to which participants replied yes or no. Individuals who responded “yes” to the risk-taking question are here referred to as “risk takers” and those who responded “no” are here referred to as “not risk takers or controls”. For a subset of participants, the same question (“Would you describe yourself as someone who takes risks?”) was asked at follow-up (2012–2013), enabling an assessment of response consistency.

Discovery analyses

A total of 116,255 individuals and 8,781,003 variants (first data release) were included in the discovery analysis. A total of 29,703 participants were classed as risk takers and 86,552 were controls. Association analysis was conducted in PLINK18 using logistic regression, assuming a model of additive allelic effects and models were adjusted for sex, age, genotyping array, and the first eight genetic PCs (Biobank Data Dictionary items #22009.01 to #22009.08) to control for hidden population stratification. The threshold for GWAS significance was set at p < 5 × 10–8. Demographics of the discovery sample set are presented in Table 1. For quality control purposes, a GWAS of the individuals included in the discovery analysis was run with the second release genetic data (HRC-imputed) and using the updated genetic exclusions and covariates used. Using the updated exclusions resulted in a slight increase in the number of individuals included in the analysis: n = 117,755, of whom n = 30,013 were risk takers and n = 87,742 were non-risk takers. The sex distribution and demographics of this data set were comparable with those included in the discovery analysis based on the first genetic release (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of UK Biobank participants included in the discovery risk-taking GWAS, replication and PRS analyses

| Discovery (1000 genomes) | Replication (HRC) | PRS (HRC) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not risk takers | Risk takersa | Not risk takers | Risk takersa | Not risk takers | Risk takersa | |

| N | 86,552 | 29,703 | 104,263 | 35,210 | 104,533 | 35,198 |

| N men | 36,679 (0.42) | 18,554 (0.63) | 41,988 (0.40) | 21,453 (0.61) | 42,161 (0.40) | 21,427 (0.61) |

| Age (years) | 57.2 (7.8) | 56.1 (8.1) | 57.2 (7.9) | 55.9 (8.2) | 57.3 (7.9) | 56.0 (8.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 (4.9) | 27.9 (4.7) | 27.2 (4.7) | 27.7 (4.7) | 27.2 (4.7) | 27.7 (4.6) |

| Current smoker | 28,575 (0.33) | 11,123 (0.38) | 35,804 (0.34) | 13,568 (0.39) | 36,219 (0.35) | 13,684 (0.39) |

| Ever smoker | 37,782 (0.44) | 16,052 (0.54) | 43,929 (0.42) | 18,265 (0.52) | 44,316 (0.43) | 18,221 (0.52) |

| Age completed educationb | 16.6 (2.1) | 16.6 (2.3) | 17.0 (2.1) | 16.7 (2.4) | 16.6 (2.1) | 16.7 (2.4) |

| Has a degree | 24,442 (0.29) | 10,235 (0.35) | 30,456 (0.29) | 12,830 (0.37) | 30,672 (0.30) | 12,731 (0.36) |

| Townsend deprivation index | −1.6 (2.9) | −1.3 (3.1) | −1.7 (2.8) | −1.4 (3.0) | −1.7 (2.9) | −1.4 (3.0) |

| Unstable mood¤ | 37,429 (0.44) | 14,258 (0.49) | 44,659 (0.44) | 16,852 (0.49) | 44,697 (0.44) | 16,722 (0.48) |

| Comparison groupc | 17,024 (0.74) | 5418 (0.69) | 20,519 (0.74) | 6350 (0.69) | 20,844 (0.74) | 6211 (0.69) |

| BD* | 190 (0.01) | 177 (0.02) | 215 (0.01) | 177 (0.02) | 206 (0.01) | 189 (0.02) |

| Single episode depressionc | 1615 (0.08) | 519 (0.07) | 1860 (0.07) | 645 (0.07) | 1838 (0.07) | 659 (0.07) |

| Moderate depressionc | 2816 (0.12) | 1034 (0.13) | 3351 (0.12) | 1289 (0.14) | 3414 (0.12) | 1207 (0.13) |

| Severe depressionc | 1486 (0.06) | 678 (0.08) | 1727 (0.06) | 797 (0.09) | 1733 (0.06) | 796 (0.09) |

| Any depression | 5917 (0.26) | 2231 (0.29) | 6938 (0.25) | 2731 (0.29) | 6985 (0.25) | 2662 (0.29) |

| Mental health questionnaire | 27,494 | 9479 | 34,011 | 11,654 | 34,060 | 11,574 |

| BD | 330 (0.01) | 232 (0.02) | 369 (0.01) | 290 (0.03) | 348 (0.01) | 277 (0.02) |

| MDD | 6450 (0.28) | 2407 (0.30) | 7716 (0.27) | 2951 (0.30) | 7896 (0.28) | 2906 (0.30) |

| GAD | 1893 (0.10) | 695 (0.11) | 2215 (0.09) | 898 (0.11) | 2431 (0.10) | 831 (0.10) |

| Any addiction | 1491 (0.05) | 918 (0.10) | 1521 (0.05) | 919 (0.08) | 1543 (0.05) | 955 (0.08) |

| Alcoholism | 569 (0.02) | 368 (0.04) | 598 (0.02) | 381 (0.03) | 576 (0.02) | 387 (0.03) |

| Illicit drug addiction | 93 (0.003) | 101 (0.01) | 70 (0.003) | 70 (0.01) | 78 (0.002) | 92 (0.01) |

| OTC/prescr~t addiction | 229 (0.01) | 96 (0.01) | 22 6 (0.01) | 125 (0.01) | 239 (0.01) | 132 (0.01) |

| Ever cannabis | 4788 (0.17) | 2780 (0.29) | 6038 (0.18) | 3432 (0.29) | 5941 (0.17) | 3356 (0.29) |

BD bipolar disorder, MDD major depressive disorder, GAD general anxiety disorder

aParticipants who answered “yes” to “do you consider yourself a risk taker?”; for continuous variables, data are presented as mean (standard deviation). For categorical variables, data are presented as n (proportion of group (i.e., risk takers or not risk takers))

bBased on a subset of 80,229 subjects; ¤ participants who answered yes to ““Does your mood often go up and down?”

cDefinitions as per Smith et al.39, based on a subset of 29,929 subjects. Addiction phenotypes based upon self-report

Replication analysis

Approximately half of the participants only present in the second data release were included in the replication analysis, thus after quality control and recommended exclusions, 139,474 white British participants were included. Demographics of the replication sample set are presented in Table 1.

The lead SNPs in the CADM2 and Chr6 loci were selected for replication. Consistent with the discovery analysis, replication analysis was conducted in PLINK18 using logistic regression, assuming a model of additive allelic effects and models were adjusted for sex, age, genotyping array, and the first eight genetic PCs (PCA1–8) to control for hidden population stratification. As two SNP were investigated, p < 0.025 was considered significant. Results were meta-analysed using METAL19.

Polygenic risk scores (PRS)

In order to assess the variance explained by the genetic loci identified here, polygenic risk scores (PRSs) were calculated in the remaining 50% of the second genetic data release. Demographics of the PRS sample set are presented in Table 1. After quality control and recommended exclusions, 139,731 white British participants were included in this analysis.

PRS were calculated using p-value thresholds of p < 1 × 10−5, p < 0.001, and p < 0.05. A score of only GWAS significant SNPs was not conducted, as a 2 SNP score (after linkage disequilibrium (LD)-based pruning) would be underpowered. LD pruning was performed via PLINK on a random sample of 10,000 individuals using an r2 > 0.05 in a 250 kb window. The SNP with the lowest p-value was selected from each of the LD-clumped SNP sets. Where two or more SNPs from a set had the same p-value, the SNP with the larger beta coefficient was used. The scores were calculated in PLINK to produce a per-allele weighted score (without mean imputation). Using STATA, deciles of scores were computed and modelling the effect of the PRS on risk was adjusted for age, sex, chip and PCs 1–8.

Data mining

SNPs associated (at genome-wide significance) with risk-taking behaviour were further investigated for influence on nearby genes (variant effect predictor, VEP20) and for reported associations with relevant traits (GWAS catalogue21). Descriptions and known or predicted functions of implicated genes were compiled (GeneCards www.genecards.org and Entrez Gene www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene) and global patterns of tissue expression were assessed (GTEx22). Exploratory analyses of the impact of significant loci on the expression of nearby genes were carried out using the GTEx Portal “Test your own eQTL” function22. In the 13 brain regions available in the GTEx data set, we tested for associations between rs13084531 and CADM2 expression, and between rs9379971 and the expression of POM121L2, PRSS16, ZNF204P and VN1R10P.

SNP heritability and genetic correlation analyses

LD score regression (LDSR)23 was applied to the GWAS summary statistics to estimate the risk-taking SNP heritability (h2SNP). LDSR was also used to assess genetic correlations between risk-taking behaviour and relevant psychiatric, cognitive and behavioural traits, namely: ADHD, SCZ, BD, MDD, anxiety, PTSD, smoking status (ever smoked), lifetime cannabis use, fluid intelligence, years of education, obesity, and alcohol use disorder.

The importance of the brain in regulation of obesity has been demonstrated24, with reward circuits being implicated. The prevalence of obesity in psychiatric illness and the possibility of over-eating being a problem behaviour suggest that there might be a connection between obesity and risk-taking behaviour. Thus, two measures of obesity were included: body mass index (BMI) as a measure of total obesity24 and waist-to-hip ratio adjusted for BMI (WHRadjBMI), reflecting metabolically detrimental central obesity25.

For the ADHD, SCZ, BD, MDD, anxiety, PTSD, and smoking status, we used GWAS summary statistics provided by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (http://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/)26–32. For the two obesity phenotypes, GWAS summary statistics for BMI24 and WHRadjBMI25 were taken from the consortium for the Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (http://portals.broadinstitute.org/collaboration/giant). Summary statistics for years of education33 and fluid intelligence34 were downloaded as instructed in the respective publications. Summary statistics for the GWAS of lifetime cannabis use were provided by the International Cannabis Consortium35. Summary statistics for GWAS of alcohol consumption36 and brain structure volumes37 were provided by the authors. Alcohol use disorder was defined using DSM-5 criteria38. For this phenotype, a GWAS meta-analysis on genotypes imputed to 1000 Genomes was run with five data sets: COGEND, COGEND2, COGEND-23andMe, COGA, and FSCD. In total, there were N = 2983 cases with alcohol use disorder and N = 1169 controls. Descriptions of the data sets are in the Supplementary information.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A subset of 20,335 participants had repeated assessment of risk-taking behaviour. Reproducibility was good, with consistent responses in 81% of all participants (inconsistent 13%, missing 6%, Supplementary Table 2). Participants with probable mood disorders39,40 showed comparable reproducibility compared with those without (consistent 80% vs 82%, inconsistent 15% vs 12%, missing 5% vs 5%, respectively).

For all analyses (discovery, replication, and PRS), small but consistent differences were observed between controls and risk takers with regard to age and BMI (Table 1), but striking differences were observed for sex distribution, smoking, and history of mood disorders: risk takers (compared with non-risk takers) were more often men, more likely to be current or ever-smokers and more likely to suffer from depression, report an addiction or to have used cannabis. Risk takers were also more likely to have a university/college degree.

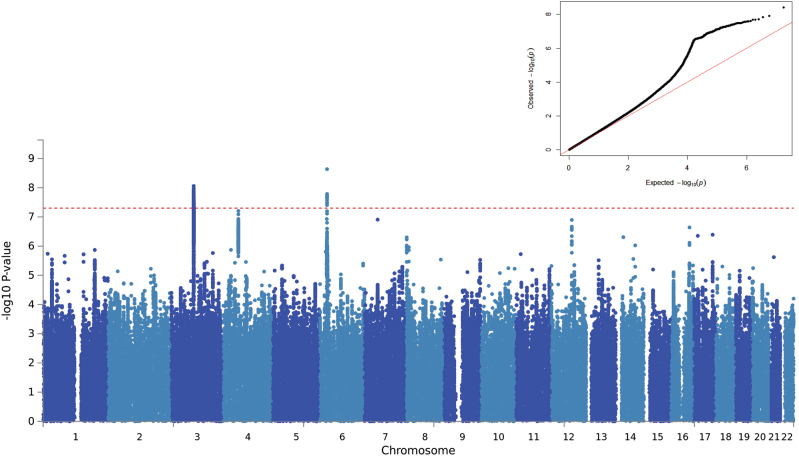

GWAS of risk-taking behaviour

GWAS results for risk taking are summarised in Fig. 1 (Manhattan plot), Fig. 1 inset (QQ plot) and Supplementary Table 3. The GWAS data test statistics showed modest deviation from the null (λGC = 1.13). Considering the sample size, the deviation was negligible (λGC 1000 = 1.002). LDSR suggested that deviation from the null was due to a polygenic architecture in which h2SNP accounted for approximately 4% of the population variance in risk-taking behaviour (observed scale h2SNP = 0.058 (SE 0.006)), rather than inflation due to unconstrained population structure (LD regression intercept = 1.003 (SE 0.008)).

Fig. 1.

Results of a genome-wide association study of self-reported risk-taking behaviour (1000 Genome imputation). SNPs are plotted along the X axis by chromosome and position, with strength of association with self-reported risk-taking behaviour plotted on the Y axis. The red line indicates the threshold for GWAS significance (p ≤ 5e−8). Inset: QQ plot demonstrates deviation from null expectation (solid red line) of the GWAS results (black data points)

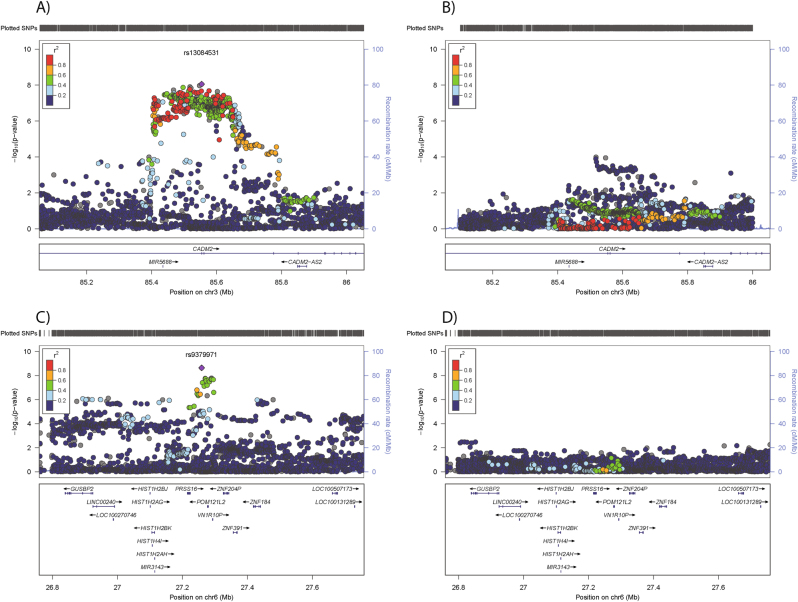

Two loci were associated with risk-taking behaviour at genome-wide significance, on chromosome 3 and chromosome 6 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3). The index SNP on chromosome (chr) 3, rs13084531, lies within the CADM2 gene, however, LD suggests that the signal also encompasses miR5688, and borders a CADM2 anti-sense transcript (CADM2-AS2, Fig. 2a). The minor allele of rs13084531 was associated with increased risk-taking (G allele, MAF 0.23, odds ratio (OR) 1.07, confidence interval (CI) 1.04–1.09, p 8.75 × 10–9). Conditional analysis of the chr3 locus (including rs13084531 as a covariate) is suggestive of a second signal (index SNP rs62250716, MAF 0.36, OR 0.96, CI 0.94–0.98, p 8.53 × 10–5, LD r2 = 0.16 with rs13084531, Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 3). The LD structure across the chr3 locus supports the possibility of two distinct signals (Supplementary Figure 1).

Fig. 2.

Regional plots for risk-taking-associated loci. a Chr3 main analysis results; b results of analysis conditioned on Chr3 rs13084531; c Chr6 main analysis results; d results of analysis conditioned on Chr6 rs9379971. The index SNP is shown as a purple diamond

The chr6 locus lies within the gene-rich human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region (Fig. 2c), where index SNP rs9379971 demonstrated an association between the minor allele and decreased risk-taking (A allele, MAF 0.35, OR 0.95, CI 0.93–0.97, p 2.31 × 10–9). Conditional analysis (including rs9379971 as a covariate) and assessment of the LD structure across this locus indicated that the associated region probably includes only one signal (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 2).

Rerunning the GWAS with the second genetic data release (Supplementary Figure 3) gave similar results, with a modest deviation from the null (λGC = 1.10, adjusted for sample size λGC 1000 = 1.002). Consistent with the 1000 Genomes analysis, LDSR suggested that deviation from the null was due to a polygenic architecture with h2SNP accounting for approximately 5% of the population variance in risk-taking behaviour (observed scale h2SNP = 0.055 (SE 0.006)). The same CADM2 locus was GWAS significant (rs62250713, beta 0.0614, SE 0.01, p = 8.289 × 10–10, minor allele A, MAF 0.36) but the locus on chromosome 6 did not meet the threshold for significance.

Replication analysis

Both the CADM2 and chr6 loci demonstrated significant (p < 0.025) associations with risk-taking behaviour in the replication analyses (Supplementary Table 4). The CADM2 locus demonstrated effect sizes comparable with those for the discovery analysis (rs13084531 beta 0.067 for discovery and beta 0.054 SE 0.011 replication). In contrast, the Chr6 locus demonstrated two- to sixfold weaker effects (rs9379971, discovery beta −0.063, replication beta −0.010). The CADM2 locus met the threshold for GWAS significance in the meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 4) but the Chr6 locus did not. The significant p-value for heterogeneity suggests that this association is a false-positive finding.

PRS analysis

The PRS were significant predictors of risk-taking behaviour, at all p thresholds and the variance explained by the model including the PRS was between 0.034 (PRS p < 1 × 10-5) and 0.037 (PRS p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 5).

Data mining

As with the majority of SNPs identified by GWAS, the genome-wide significant SNPs in both loci are non-coding. Current prediction models ascribe only non-coding modifier functions to the 81 genome-wide significant SNPs (VEP20, Supplementary Table 6). Expression quantitative trait analysis directly tests association of the index SNPs with expression of nearby transcripts. The chr3 index SNP (rs13084531) lies within the CADM2 gene and adjacent to a micro RNA, miR5688, and CADM2-AS2 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 7). Currently, most miRs are predicted (but not reliably proven) to influence transcription of hundreds or thousands of genes. Furthermore, analysing transcription levels of miRs is challenging. Similarly, the importance of anti-sense transcripts such as CADM2-AS2 is unclear and difficult to assess. CADM2, which encodes cell adhesion molecule 2 (also known as synaptic cell adhesion molecule, SynCAM2), is a plausible target gene as it is predominantly expressed in the brain (Supplementary Figure 4A). The risk allele at rs13084531 was associated with increased CADM2 mRNA levels in several regions of the brain (including the caudate basal ganglia and putamen basal ganglia, hippocampus and hypothalamus, Supplementary Figure 5). CADM1, a related cell adhesion molecule, demonstrates overlapping and co-regulated (albeit inversely) expression patterns41. It is worth noting that CADM1 shows a similar, albeit less brain-specific, expression pattern (Supplementary Figure 4B) and that genetic deletion of Cadm1 in mice results in behavioural abnormalities, including anxiety42.

Excitement-seeking is a behavioural trait closely related to risk-taking behaviour43, however, the locus reported for excitement seeking was nonsignificant in this study (Chr2, rs11126769, LD R2 with the reported rs7600563 = 0.862, major T allele, Beta 0.016, SE 0.011, p = 0.1167). Other potentially problematic behaviours, which can be related to risk-taking propensity, have identified the CADM2 locus (Supplementary Table 8): a recent GWAS of alcohol consumption44 identified a significant signal in the CADM2 locus, where the G allele of rs9841829 was associated with increased alcohol consumption. The same SNP demonstrates genome-wide significance with increased risk-taking behaviour in this study (G, Beta 0.0635, SE 0.012 p = 3.34 × 10−8, Supplementary Table 3), whereas conditional analysis (Supplementary Table 3) indicates that the signal for alcohol consumption and risk-taking is the same. A GWAS of lifetime cannabis use also highlighted the CADM2 locus (gene-based rather than SNP-based)35. Cognitive function plays a role in traits such as risk-taking, therefore it is worth noting that a GWAS of executive functioning and information processing speed in non-demented older adults from the CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology) consortium found that genetic variation in the CADM2 gene was associated with individual differences in information processing speed45. The allele of rs17518584 (LD r2 = 0.45 with rs13084531, LD r2 = 0.34 with rs62250716) associated with increased processing speed was associated with reduced (self-reported) risk-taking in the current study (Supplementary Table 8, p = 1.17 × 10−7). Furthermore, a GWAS of educational attainment in the UK Biobank cohort demonstrated a significant signal in CADM246. The effect allele of rs56262138 (LD r2 = 0.00 with rs13084531, LD r2 = 0.00 with rs62250716) for increased educational attainment showed a negative effect on risk-taking behaviour (Supplementary Table 8, p = 0.0210).

Day et al. reported an association between the CADM2 locus and age of reproductive onset in UK Biobank. In a secondary analysis, they also report an association between the same locus, CADM2, and risk-taking behaviour (the same phenotype as was used here). However, differences in quality control procedures mean that the lead SNP reported by Day et al. was not available in our analysis. During the revision of this paper, Boutwell et al.10 replicated the association between the CADM2 locus and a number of personality traits including risk-taking (“do you feel comfortable or uncomfortable with taking risks?”), in an independent data set (n ~ 140,000).

The CADM2 locus has also been tentatively associated with longevity47 ((Supplementary Table 8) rs9841144, LD r2 = 0.99 with rs13084531, LD r2 = 0.16 with rs62250716), but associations between CADM2 SNPs and longevity, survival and attaining 100 years of age in that study were inconsistent, limiting the interpretation of these signals in the context of risk-taking behaviour.

Genetic correlations

Looking up the risk-taking SNPs in the GWAS results of psychiatric conditions demonstrated little or no effect of the CADM2 SNPs in ADHD, SCZ, PTSD, BPD, or MDD (Supplementary Table 9). In contrast, when considering the entire genome, we found significant positive genetic correlations between the risk-taking phenotype and ADHD (rg = 0.31, SE = 0.13, p = 0.01), SCZ (rg = 0.27, SE = 0.04, p = 4.54 × 10−11), BD (rg = 0.26, SE = 0.07, p = 1.73 × 10−4), PTSD (rg = 0.51, SE = 0.17, p = 0.0018), lifetime cannabis use (rg = 0.41, SE = 0.11, p = 0.0001), and smoking (rg = 0.17, SE = 0.07, p = 0.01) and a negative genetic correlation with fluid intelligence (rg = −0.15, SE = 0.05, p = 0.0013, Table 2). We found no significant genetic correlation between risk-taking and MDD, anxiety, or years of education (Table 2). There was also a significant genetic correlation between risk-taking and BMI (rg = 0.10, SE = 0.03, p = 0.003), but a similar correlation was not found for WHRadjBMI. The nonsignificant genetic correlation with alcohol use disorder was interesting because of the strength of the coefficient (rg = 0.22, SE0.31, p = 0.47), however, was likely underpowered due to the modest size of the GWAS (n = 4 171) and we draw no conclusions about this correlation.

Table 2.

Genetic correlation between risk-taking and traits relevant to psychiatric disorders

| Phenotype | rg | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | 0.378 | 0.054 | 1.80 × 10−12 |

| SCZ | 0.265 | 0.040 | 4.54 × 10−11 |

| BD | 0.261 | 0.070 | 1.73 × 10−4 |

| MDD | 0.069 | 0.084 | 0.4120 |

| PTSD | 0.513 | 0.165 | 0.0018 |

| Anxiety (case control) | −0.090 | 0.132 | 0.4963 |

| Anxiety (quantitative) | −0.123 | 0.156 | 0.4289 |

| Ever smoker | 0.174 | 0.068 | 0.0102 |

| Alcohol (heavy vs light) | 0.249 | 0.234 | 0.2873 |

| Alcohol (quantitative) | 0.248 | 0.082 | 0.0026 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 0.221 | 0.306 | 0.4700 |

| Lifetime cannabis use | 0.406 | 0.107 | 1.00 × 10−4 |

| Caudate volume | 0.049 | 0.078 | 0.5268 |

| Accumbens volumes | 0.195 | 0.143 | 0.1710 |

| Fluid intelligence | −0.151 | 0.047 | 0.0013 |

| Years of education | −0.023 | 0.033 | 0.4873 |

| BMI | 0.102 | 0.034 | 0.0028 |

| WHRadjBMI | 0.087 | 0.047 | 0.0655 |

Bold indicates significant p values

MDD major depressive disorder, BD bipolar disorder; SCZ schizophrenia, ADHD attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, BMI body mass index, WHRadjBMI waist:hip ratio adjusted for BMI. Alcohol dependence DSM-5 criteria: rg, regression coefficient, se, standard error of the regression coefficient

p, p-value for the regression analysis

Discussion

There is a growing emphasis on the importance of using phenotypic traits, which cut across traditional diagnostic groups to investigate the biological basis of psychiatric disorders. Risk-taking behaviour is one such trans-nosological characteristic, recognised clinically as a feature of several disorders, including ADHD, SCZ, and BD. In this study, we identified two loci, on 3p12.1 and 6p22.1, which were associated with self-reported risk-taking behaviour. Replication in an independent set of samples and meta-analysis confirmed the association between risk-taking behaviour and the CADM2 locus on Chr3 but not the Chr6 locus. The PRS were significant predictors of risk-taking behaviour in a further independent sample set.

The chr6 locus falls within the HLA region, which encodes a large number of genes and is extremely complicated genetically. The false-positive association detected could be because the first data release were selected based on (extremes of) lung function measurements48. Considering the potential inflammatory component of lung function and the role of the HLA region in inflammatory responses, it is perhaps not surprising that the discovery analysis demonstrated stronger effect sizes for this locus than the randomly selected general population samples included in the replication analysis.

A key finding of our study was the positive association between Chr3 SNP, rs13084531, and risk-taking behaviour, as well as CADM2 expression levels. Here, the allele associated with increased self-reported risk-taking behaviour was also associated with increased CADM2 expression. It is of interest that lack of Cadm1 in mice was associated with anxiety-related behaviour42 and that both CADM1 and CADM2 were identified as BMI-associated loci24 suggesting that CADM2 and related family members may be involved in balancing appetitive and avoidant behaviours.

Day and colleagues recently identified 38 genome-wide significant loci for age at first sexual intercourse within the UK Biobank cohort2 and two of these loci were within the 3p12.1 region, close to CADM2 (rs12714592 and rs57401290). The association between rs57401290 (and SNPs in LD) and age at first sexual intercourse was also observed for a number of behavioural traits, including number of sexual partners, number of children, and risk-taking propensity (the same phenotype as was used in this study). In addition, CADM2 also showed association with information processing speed45 and educational attainment46, highlighting the complexity of relationships between cognitive performance and risk taking. Taken together, this evidence suggests that CADM2 plays a fundamental role in risk-taking behaviours, and may be a gene involved in the nexus of cognitive and reward-related processes that underlie them.

A perhaps surprising observation was the increased frequency of having a university degree in self-reported risk takers, compared with controls, despite the negative (albeit nonsignificant) association between years of education and risk-taking behaviour. It is important to note that risk-taking behaviour includes a number of different aspects, including delayed gratification, assessment of positive and negative consequences of risk, impulse control, reward signalling. It is possible that risk-taking behaviour assessed in a clinical mental health setting could reflect a different aspect of these processes compared with self-reported risk-taking behaviour. Risk-taking behaviour assessed in a clinical mental health setting might demonstrate significantly different associations with education, compared with self-reported risk-taking behaviour. These observations underscore the complexity between risk-taking and educational attainment, and highlight differences between genetic and phenotypic relationships. They may also be indicative of selection bias within the UK Biobank cohort towards more highly educated individuals.

Another key finding was genetic correlation between self-reported risk taking and obesity. Although there are likely to be a range of potential mechanisms linking risk-taking behaviour with obesity, evidence of a shared genetic component is in keeping with work that has highlighted the importance of the central nervous system in the regulation of obesity (BMI), particularly brain regions involved in cognition, learning, and reward24. In contrast, central fat accumulation (WHRadjBMI) is primarily regulated by adipose tissue25, which fits with the lower, nonsignificant genetic correlation between risk-taking behaviour and this measure. Two SNPs (rs13078807 and rs13078960) in the CADM2 locus have previously been associated with BMI24,49,50, but while these SNPs tag each other (LD r2 = 0.99), the LD between the risk-taking index SNP or possible secondary signal is low (LD r2 = 0.31 and 0.01 for rs13084531 and rs62250716, respectively), suggesting that these are distinct signals.

It is perhaps unsurprising that we identified genetic correlations between risk taking and smoking. Similarly, risk taking and impulsive behaviour is a core feature of ADHD and BD, suggesting substantial genetic overlap between variants predisposing to risk-taking behaviour and these disorders. The genetic correlation between risk taking and SCZ is of interest because SCZ is commonly comorbid with substance abuse disorders51. The correlation between risk taking and PTSD is perhaps plausible if we accept that risk takers may be more likely to find themselves in high-risk situations with the potential to cause psychological trauma. Overall, these correlations suggest that studying dimensional traits such as risk-taking has the potential to inform the biology of complex psychiatric disorders.

Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge that Day et al. have previously reported an association for risk taking within the CADM2 locus. Strengths of our study include the use of a more conservative and standardised methodology and reporting of results across the entire genome. A risk-taking locus was identified in the CADM2 locus and we have shown that CADM2 may contain a second signal. Furthermore, we have investigated the possibility of a sex-specific effect of these loci, provided evidence highlighting possible candidate genes at both loci and confirmed the importance of this phenotype in relation to psychiatric illness. In short, our report provides a fuller understanding of the genetic basis of risk-taking behaviour. Despite this, we highlight some limitations. The risk-taking phenotype used was a self-reported measure, based on response to a single question, and is therefore open to responder bias. It is also plausible that there are distinct subtypes of risk-taking behaviour (for example disinhibition, sensation seeking, and calculated risks). Whether the single question used in our analyses captures all, or only some, of these is not clear. Having identified genetic loci associated with other traits related to risk taking and other problem behaviours (such as alcohol consumption and cannabis use) provides added support for the validity of this phenotype. It would be of interest to investigate whether the loci identified here are also associated with more quantitative and objective measures of risk taking; however, such measures were not available in the UK Biobank data set.

Conclusion

In summary, we have identified a polygenic basis for self-reported risk-taking behaviour and the CADM2 locus, which contains variants likely to play a role in predisposition to this complex but important phenotype. The identification of significant genetic correlations between risk taking and several psychiatric disorders, as well as with smoking and obesity, suggest that future work on this trait may clarify mechanisms underlying several common psychopathological and physical health conditions, which are important for public health and well-being.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted using the UK Biobank resource. UK Biobank was established by the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, Department of Health, Scottish Government, and Northwest Regional Development Agency. UK Biobank has also had funding from the Welsh Assembly Government and the British Heart Foundation. Data collection was funded by UK Biobank. J.W. is supported by the JMAS Sim Fellowship for depression research from the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (173558). A.F. is supported by an MRC Doctoral Training Programme Studentship at the University of Glasgow (MR/K501335/1). D.J.S. acknowledges the support of the Brain and Behaviour Research Foundation (Independent Investigator Award 1930) and a Lister Prize Fellowship (173096). E.M.T. is supported by a University Research Fellowship (UF140705) from the Royal Society. J.C. acknowledges the support of The Sackler Trust and is part of the Wellcome Trust funded Neuroimmunology of Mood and Alzheimer’s consortium that includes collaboration with GSK, Lundbeck, Pfizer and Janssen & Janssen. The work at Cardiff University was funded by Medical Research Council (MRC) Centre (G0800509) and Program Grants (G0801418). The funders had no role in the design or analysis of this study, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

J.P.P. is a member of UK Biobank advisory committee; this had no bearing on the study. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Rona J. Strawbridge and Joey Ward contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41398-017-0079-1.

References

- 1.Schoenfelder EN, Kollins SH. Topical review: ADHD and health-risk behaviors: toward prevention and health promotion. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016;41:735–740. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Day FR, et al. Physical and neurobehavioral determinants of reproductive onset and success. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:617–623. doi: 10.1038/ng.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinharth J, Braga R, Serper M. Characterization of risk-taking in adults with bipolar spectrum disorders. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017;205:580–584. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Haan L, Egberts AC, Heerdink ER. The relation between risk-taking behavior and alcohol use in young adults is different for men and women. Drug. Alcohol Depend. 2015;155:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreek MJ, Nielsen DA, Butelman ER, LaForge KS. Genetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/nn1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kornreich C, et al. Conditional reasoning in schizophrenic patients. Evol. Psychol. 2017;15:1474704917721713. doi: 10.1177/1474704917721713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng GL, Tang JC, Li FW, Lau EY, Lee TM. Schizophrenia and risk-taking: impaired reward but preserved punishment processing. Schizophr. Res. 2012;136:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cope EC, Gould E. New evidence linking obesity and food addiction. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;81:734–736. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.02.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Med. 2013;11:126. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boutwell B, et al. Replication and characterization of CADM2 and MSRA genes on human behavior. Heliyon. 2017;3:e00349. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy LF, et al. Impulsivity and risk taking in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:456–463. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudlow C, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS. Med. 2015;12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UK Biobank. Genotype imputation and genetic association studies of UK Biobank, Interim Data Release (2015)..

- 14.Delaneau O, Zagury JF, Marchini J. Improved whole-chromosome phasing for disease and population genetic studies. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:5–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howie B, Marchini J, Stephens M. Genotype imputation with thousands of genomes. G3 (Bethesda) 2011;1:457–470. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J, et al. Improved imputation of low-frequency and rare variants using the UK10K haplotype reference panel. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8111. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UK Biobank. Genotyping of 500,000 UK Biobank participants. Description of sample processing workflow and preparation of DNA for genotyping. https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/docs/genotyping_sample_workflow.pdf (2015).

- 18.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLaren W, et al. The Ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17:122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacArthur J, et al. The new NHGRI-EBI catalog of published genome-wide association studies (GWAS catalog) Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D896–D901. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.GTEx Consortium. The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet.45, 580–585 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Bulik-Sullivan B, et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1236–1241. doi: 10.1038/ng.3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Locke AE, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shungin D, et al. New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature. 2015;518:187–196. doi: 10.1038/nature14132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genetics Consortium. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat. Genet.43, 969–976 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Ruderfer DM, Fanous AH, Ripke S, McQuillin A, Amdur RL. Schizophrenia Working Group of Psychiatric Genomics C et al. Polygenic dissection of diagnosis and clinical dimensions of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:1017–1024. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genetics Consortium, Ripke, S. et al. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressivedisorder. Mol. Psychiatry18, 497–511 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Neale BM, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010;49:884–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabacco and Genetics Consortium. Genome-wide meta-analyses identify multiple loci associated with smoking behavior. Nat. Genet.42, 441–447 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Duncan, L. E. et al. Largest GWAS of PTSD (N = 20 070) yields genetic overlap with schizophrenia and sex differences in heritability. Mol. Psychiatry10.1038/mp.2017.77 (2017).. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Otowa T, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of anxiety disorders. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:1485. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okbay A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature. 2016;533:539–542. doi: 10.1038/nature17671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sniekers S, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of 78,308 individuals identifies new loci and genes influencing human intelligence. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1107–1112. doi: 10.1038/ng.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stringer S, et al. Genome-wide association study of lifetime cannabis use based on a large meta-analytic sample of 32 330 subjects from the International Cannabis Consortium. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;6:e769. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schumann G, et al. KLB is associated with alcohol drinking, and its gene product beta-Klotho is necessary for FGF21 regulation of alcohol preference. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:14372–14377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611243113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hibar DP, et al. Common genetic variants influence human subcortical brain structures. Nature. 2015;520:224–229. doi: 10.1038/nature14101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, DSM-5. (American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, 2013).

- 39.Smith DJ, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of probable major depression and bipolar disorder within UK biobank: cross-sectional study of 172,751 participants. PLoS. ONE. 2013;8:e75362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis K. A. S. et al. Mental Health in UK Biobank—development, implementation and results from an online questionnaire completed by 157,366 participants. BJPsych. Open (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 41.Pietri T, Easley-Neal C, Wilson C, Washbourne P. Six cadm/SynCAM genes are expressed in the nervous system of developing zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 2008;237:233–246. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanabe Y, et al. Synaptic adhesion molecules in Cadm family at the neuromuscular junction. Cell. Biol. Int. 2013;37:731–736. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terracciano A, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies common variants in CTNNA2 associated with excitement-seeking. Transl. Psychiatry. 2011;1:e49. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toni-Kim Clarke, Mark J et al. Genome-wide association study of alcohol consumption and genetic overlap with other health-related traits in UK Biobank (N = 112,117). 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, et al. GWAS for executive function and processing speed suggests involvement of the CADM2 gene. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:189–197. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davies G, et al. Genome-wide association study of cognitive functions and educational attainment in UK Biobank (N = 112 151) Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:758–767. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broer L, et al. GWAS of longevity in CHARGE consortium confirms APOE and FOXO3 candidacy. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015;70:110–118. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wain LV, et al. Genome-wide association analyses for lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease identify new loci and potential druggable targets. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:416–425. doi: 10.1038/ng.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berndt SI, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 11 new loci for anthropometric traits and provides insights into genetic architecture. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:501–512. doi: 10.1038/ng.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Speliotes EK, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thoma P, Daum I. Comorbid substance use disorder in schizophrenia: a selective overview of neurobiological and cognitive underpinnings. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013;67:367–383. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.