Abstract

We aimed to examine the effects of zinc supplementation on nutritional status, lipid profile, and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory therapies in maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials of zinc supplementation. Metaregression analyses were utilized to determine the cause of discrepancy. Begg and Egger tests were performed to assess publication bias. Subgroup analysis was utilized to investigate the effects of zinc supplementation in certain conditions. In the crude pooled results, we found that zinc supplementation resulted in higher serum zinc levels (weighted mean difference [WMD] = 28.489; P < 0.001), higher dietary protein intake (WMD = 8.012; P < 0.001), higher superoxide dismutase levels (WMD = 357.568; P = 0.001), and lower levels of C-reactive protein (WMD = −8.618; P = 0.015) and malondialdehyde (WMD = −1.275; P < 0.001). The results showed no differences in lipid profile. In the metaregression analysis, we found that serum zinc levels correlated positively with intervention time (β = 0.272; P = 0.042) and varied greatly by ethnicity (P = 0.023). Results from Begg and Egger tests showed that there was no significant bias in our meta-analysis (P > 0.1). Results of subgroup analysis supported the above results. Our analysis shows that zinc supplementation may benefit the nutritional status of MHD patients and show a time-effect relationship.

1. Introduction

Zinc is an essential trace element for humans which is found in nearly 100 specific enzymes. Zinc plays “ubiquitous biological roles” in physiological function, including gene expression, protein synthesis, immune function, and behavioral responses [1–3]. Although the prevalence of zinc deficiency is still unclear in patients with maintenance hemodialysis (MHD), some data show adverse outcomes that may attribute to zinc deficiency [4, 5]. Malnutrition, as an independent risk factor of cardiovascular events, and death are the most common complications observed in MHD patients [6, 7]. Some studies have reported the potential relationship between zinc deficiency and other imbalances, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, or immunosuppression [8, 9], and these disorders may contribute to poor prognosis of disease.

Many previous studies have investigated the effects of zinc supplementation in MHD patients. The relevant results show that zinc supplementation can improve a number of disorders including low-grade inflammatory process, protein-energy wasting, and impaired immune response [10, 11]. However, to our knowledge, there may be some inadequacies in separate clinic trials. For example, in a separate randomized controlled trial (RCT), it is hard to identify the effects of zinc supplementation in MHD patients with different races and varying intervention dosages. The existing data showed different and even contradictory results simultaneously within different studies [12, 13]. Yet, no studies have focused on the causes of heterogeneity. The incomparable evidences make it hard to assess the actual effects of zinc supplementation in MHD patients. These controversies may be ascribed to inadequate data and differences in experimental designs between the published investigations. A meta-analysis may help to find the sources of heterogeneity and clarify the effects of zinc supplementation on nutritional status, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

In this study, we collected relevant RCTs for systematic review and performed meta-analyses to comprehensively investigate the relationships between nutritional status, oxidative stress, and inflammation and zinc supplementation in MHD patients. Subsequently, we aimed to find conflicting results and analyze their causes. Our study may add to the existing literature.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

Systematic literature searches were conducted in the following electronic databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Chinese Biomedical Literature, and the Cochrane Library. The relevant articles were published before January 15, 2016. Only publications with sufficient data were included for assessment. The following search terms were used: [Hemodialysis OR Dialysis OR Renal Replacement Therapy OR End Stage Renal Disease] AND [Zinc OR Zn] AND [Random ∗ OR Randomized Controlled Trial OR Randomized Controlled Trial as Topic] AND [Nutrition OR Nutritional Status OR Reactive Oxygen OR Oxidative Stress OR Inflammation].

To identify additional potentially relevant publications, the related references from all retrieved articles and reviews were manually searched. Only published studies with full-text articles were included in the meta-analysis. All data were entered into the Review Manager 5.0 software (Biostat, NJ, USA) by one author and checked by another author. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two authors and by seeking the opinion of a third party when necessary.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Types of studies included published reports of RCTs comparing zinc supplementation with controls (placebo or blank control) with available data for outcomes. Type of participants included studies that were restricted to any patients with MHD therapy stability. Records of the basic characteristics of participants (age, sex ratio, and dialysis duration) were required. Type of intervention included studies comparing zinc supplementation with a control for MHD patients. The dose of zinc compounds (zinc sulfate, zinc gluconate, or zinc aspartate) was converted to elemental zinc dose. The control intervention included placebo and blank control.

All outcomes were extracted for type of outcome measures. Only outcomes measured in at least 2 studies were included for the meta-analysis and were as follows: nutritional status: serum zinc levels, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), normalized protein equivalent of nitrogen appearance rate (nPNA, g/kg/d), dietary protein intake (g/kg/d), albumin (g/dL), hemoglobin, triglycerides (g/dL), total cholesterol (mg/dL), low density lipoprotein (mg/dL), and high density lipoprotein (mg/dL) levels; inflammation: C-reactive protein (CRP, ng/mL); and oxidative stress: malondialdehyde (MDA, nmol/mL) and superoxide dismutase (SOD, U/g Hb).

Studies were excluded if there is lack of data regarding oral dosage of zinc or intervention time. Trials of sexual dysfunction were also excluded due to prior analysis. If any studies included multiple publications on the same RCT, we chose the one with the highest quality according to the study quality assessment.

2.3. Study Quality Assessment

The method quality of each study was evaluated by 2 authors independently using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool that included 6 evaluation criteria [14]: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation sequence concealment (selection bias), blinding (performance and detection bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), and other potential sources of bias. The judgment for each criterion was indicated as “low risk of bias,” “high risk of bias,” or “unclear risk of bias.”

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two independent investigators performed data extraction using the inclusion criteria as described above. All discrepancies were resolved by discussion and, if required, participation by a third author. The following information was extracted from each study: first author's surname, year of publication, race and geographical location of the study, sample size, age, base disease, dialysis duration, oral zinc dose, the control intervention (placebo or blank control), and outcomes. The 2 investigators' results were compared, and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 10.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The effect of each outcome was determined by calculating the respective weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity of the effect size was evaluated using the Q and I-squared statistics. A fixed effects model was used when the P value was >0.05 and I-squared was <50%; otherwise, a random effects model was used. The significance of the pooled WMD was determined using a Z test. We used Begg and Egger tests to investigate the publication bias of our meta-analysis. To explore the sources of heterogeneity, we performed a meta-regression analysis. Subgroup analyses were also used to evaluate the effect in various conditions. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. The above work was completed by 2 authors and checked by a third author.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies

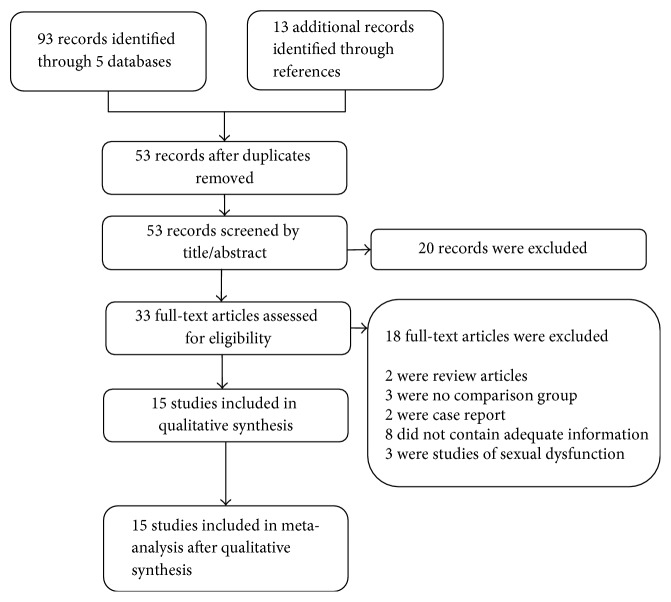

A total of 106 relevant published articles were identified following the aforementioned retrieval strategy. After strict review, 91 of these publications were excluded (73 records were screened by title/abstract and 18 records were screened by full-text) and 15 relevant published articles were identified and selected for our meta-analysis (Figure 1). The included studies enrolled a total of 645 MHD patients, among which 345 were treated with zinc supplementation and 300 were treated with placebo or as blank control. Of these included studies, 8 were West Asian (Iran, Turkey, and Egypt), 5 were European or American (United Kingdom, United States, and Mexico), and 2 were East Asian trials (Taiwan and Japan). All studies included patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and one complicated low protein catabolic rate. Mean age of participants ranged from 13 to 80 years with dialysis for at least 3 months. The elemental zinc doses ranged from 11 to 100 mg and follow-up ranged from 40 to 360 days. The main characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Reference | Year | Region | Number of patients (M/F)a | Age (Year)b | Primary disease | Dialysis duration | Elemental zinc dose | Intervening time | Comparative approach | Outcomesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kobayashi et al. | [15] | 2015 | Japan | 70 (43/27) | 69 ± 10 | CKD | - | 34 mg/day | 90/180/270/ 360 days |

Blank | Serum zinc, hemoglobin, RBC, ESA, ERI |

| El-Shazly et al. | [16] | 2015 | Egypt | 30 (29/31) | 13.2 ± 2.1 | CKD | ≥6 months | 16.5 mg/day | 90 days | Palcebo | Serum zinc, leptin, body weight, BMI |

| Argani et al. | [17] | 2014 | Iran | 60 (36/24) | (50, 60) | CKD | -c | 90 mg/day | 60 days | Palcebo | Serum zinc, albumin, BMI, body fat, body water, Ccr, hematocrit, hemoglobin, leptin, TC, TG |

| Pakfetrat et al. | [18] | 2013 | Iran | 97 (55/42) | 51.6 ± 16.8 | CKD | >3 months | 50 mg/day | 43 days | Placebo | Serum zinc, HCys, homocysteine |

| Mazani et al. | [19] | 2013 | Iran | 65 (41/24) | 52.7 ± 12.6 | CKD | >6 months | 100 mg/day | 60 days | Placebo | Serum zinc, BMI, GSH, MDA, SOD, TAC |

| Guo and Wang | [8] | 2013 | Taiwan | 65 | 59.7 ± 9.2 | CKD | >3 months | 11 mg/day | 56 days | Blank | Serum zinc, hematocrit, albumin, CD4/CD8, CRP, GFR, IL-6, MDA, nPNA, Cu, SOD, TNF-α, Vit C/E |

| Rahimi-Ardabili et al. | [20] | 2012 | Iran | 60 (38/22) | 52.7 ± 12.7 | CKD | ≥6 months | 100 mg/day | 60 days | Placebo | TC, Apo-AI, Apo-B, HDL, LDL, PON, TG |

| Roozbeh et al. | [21] | 2009 | Iran | 53 (28/25) | 55.7 | CKD | ≥6 months | 45 mg/day | 42 days | Placebo | Serum zinc, HDL, LDL, TC, TG |

| Rashidi et al. | [22] | 2009 | Iran | 55 (32/23) | 57.6 | CKD | ≥6 months | 45 mg/day | 42 days | Placebo | Serum zinc, CRP, hemoglobin |

| Nava-Hernandez and Amato | [23] | 2005 | Mexico | 25 | 16.6 | CKD | - | 100 mg/day | 90 days | Placebo | Albumin, pre-albumin, transferrin |

| Matson et al. | [12] | 2003 | UK | 15 (11/4) | 63.73 | CKD | ≥3 months | 45 mg/day | 42 days | Placebo | Serum zinc, albumin, Kt/V, calcium, CRP, nPNA, phosphate |

| Chevalier et al. | [24] | 2002 | USA | 27 (22/6) | 51.9 | CKD | ≥6 months | 50 mg/day | 40/90 days | Placebo | Serum zinc, dietary intake, HDL, LDL, TC |

| Candan et al. | [25] | 2002 | Turkey | 34 (18/16) | 45.6 (28, 64) | CKD | - | 20 mg/day | 90 days | Placebo | Serum zinc, MDA, OSMO fragility |

| Jern et al. | [26] | 2000 | USA | 14 | 56.5 (23, 80) | CKD with low PCR | ≥6 months | 45 mg/day | 40/90 days | Placebo | Serum zinc, dietary intake, nPNA |

| Brodersen et al. | [27] | 1995 | German | 40 (22/18) | 60 | CKD | - | 60 mg/day | 112 days | Blank | Serum zinc |

Note. aSex ratio: M = male, F = female; bage appears as mean, mean ± standard deviation or mean (lower limit, upper limit); c-: no information was recorded in included study. Abbreivations. RBC, red blood cell; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; ERI, ESA resistance index; BMI, body mass index; Ccr, creatinine clearance rate; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; MDA, malondialdehyde; nPNA, normalized protein equivalent of nitrogen appearance; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

3.2. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

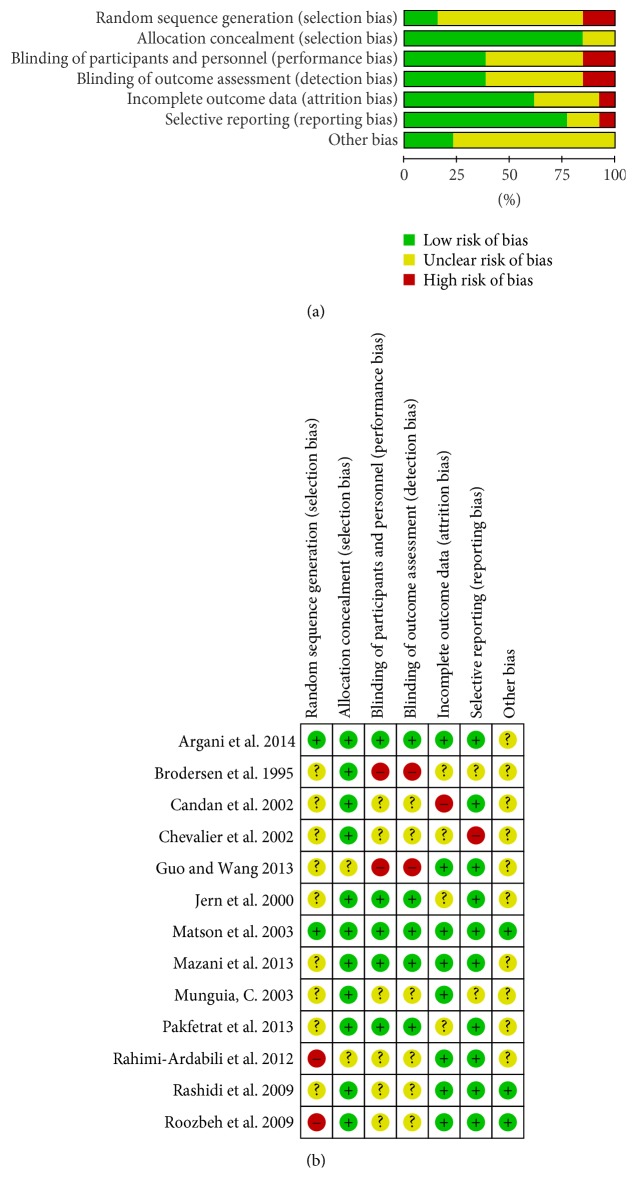

Of the 15 included studies, all claimed to apply randomized methods; however, only 2 used such methods (drawing random numbers). One clearly described allocation concealment (third party ensuring). Ten studies had a double-blinded design, but the details were unclear. Only one study described the pharmacy clinical trials unit as a third party, ensuring a double-blinded design. Eight studies reported withdrawals, but the results were not analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. Of the 15 included studies, 8 reported all expected outcomes. Only 4 studies reported dietary restrictions. This may have caused potential bias due to insufficient information in the included trials. A summary of findings is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph and bias summary: (a) review of authors' judgments regarding each risk of bias item for each included study and (b) review of authors' judgments regarding each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.3. Crude Pooled Results of Each Outcome

In the crude analysis, we found that levels of serum zinc, dietary protein intake, and SOD in the zinc supplementation group were higher than levels in control group after treatment. The pooled WMDs were statistically significant (serum zinc: WMD = 28.489, 95% CI = 26.264 to 30.713, P < 0.001; dietary protein intake: WMD = 8.012, 95% CI = 1.592 to 14.408, P < 0.001; SOD: WMD = 357.568, 95% CI = 152.158 to 562.978, P = 0.001). CRP and MDA levels were lower after zinc supplementation (CRP: WMD = −8.618, 95% CI = −15.579 to −1.656, P = 0.015; MDA: WMD = −1.275, 95% CI = −1.945 to −0.605, P < 0.001). The results showed no differences in BMI, nPNA, hemoglobin, or lipid profile (P > 0.05). Heterogeneity was significant in the results. Of the 15 pooled outcomes, 10 showed obvious heterogeneity (I-squared > 50%, P < 0.1). Results from Begg and Egger tests showed that there was no significant bias in our meta-analysis (P > 0.1). All data are presented in Table 2. Relative bioavailability of zinc sulfate, gluconate, and aspartate may be different and worth further analysis. For inadequate reports, meta-analysis for effect of different zinc compounds was not performed.

Table 2.

Summary of the effects of zinc supplementation in MHD patients.

| Factor | Number of studies | Heterogeneity test | Weighted mean difference | Publication bias | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | I 2 | P value | WMD | [95% CI] | P value | Begg test | Egger test | ||

| Serum zinc (ug/dL) | 13 | 81.98 | 90.7% | <0.001 | 28.489 | [26.264, 30.713] | <0.001∗ | 0.502 | 0.355 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 3 | 1.34 | 0% | 0.511 | 0.149 | [−0.762, 1.059] | 0.794 | 1.000 | 0.263 |

| nPNA (g/kg/d) | 4 | 11.31 | 91.20% | 0.001 | 0.135 | [−0.161, 0.431] | 0.371 | 1.000 | 0.657 |

| Dietary protein intake (g/kg/d) | 2 | 0.27 | 0% | 0.604 | 8.012 | [1.592, 14.408] | <0.001∗ | - | - |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4 | 9.74 | 69.20% | 0.021 | 0.358 | [−0.016, 0.732] | 0.061 | 0.734 | 0.276 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 4 | 16.27 | 81.6% | 0.013 | 0.756 | [−0.011, 1.522] | 0.053 | 1.000 | 0.654 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 4 | 24.6 | 91.90% | <0.001 | 4.048 | [−3.142, 11.238] | 0.27 | 1.000 | 0.847 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 4 | 24.46 | 91.80% | <0.001 | 21.028 | [−15.478, 57.534] | 0.259 | 1.000 | 0.749 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 5 | 22.97 | 86.90% | <0.001 | 16.198 | [−9.975, 42.371] | 0.225 | 0.734 | 0.624 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 3 | 8.2 | 75.60% | 0.017 | 0.207 | [−34.711, 35.125] | 0.991 | 1.000 | 0.327 |

| CRP (ng/mL) | 3 | 13.85 | 85.60% | 0.001 | −8.618 | [−15.579, −1.656] | 0.015∗ | 1.000 | 0.783 |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 3 | 16.32 | 87.70% | <0.001 | −1.275 | [−1.945, −0.605] | <0.001∗ | 0.296 | 0.287 |

| SOD (U/g Hb) | 2 | 3.42 | 70.80% | 0.064 | 357.568 | [152.158, 562.978] | 0.001∗ | - | - |

Note. -: values could not be calculated due to an insufficient number of studies; ∗P < 0.05, and WMD was considered statistically significant.

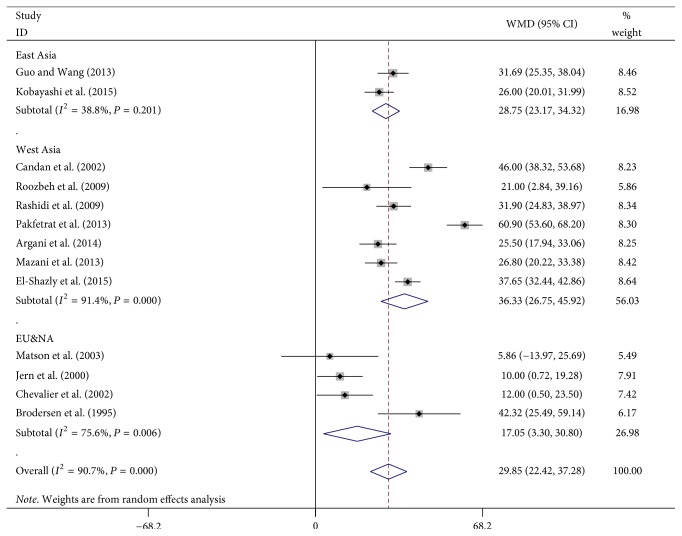

3.4. Results of Metaregression and Region-Subgroup Analysis

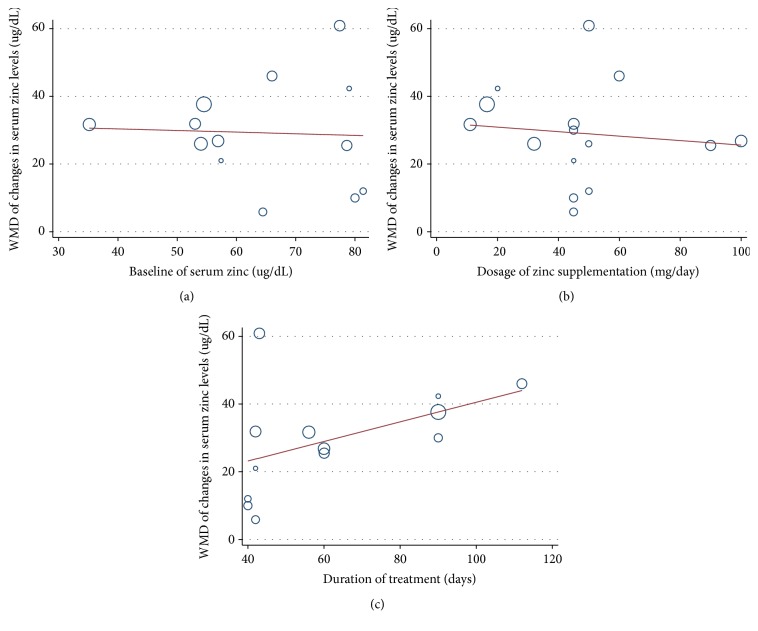

To explore the sources of heterogeneity, we performed a metaregression analysis on serum zinc levels. Oral zinc dose, intervention time, baseline of serum zinc, and region of study were selected as dependent variables. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, we found that serum zinc levels correlated positively with intervention time (β = 0.272, P = 0.042). Subgroup data suggested a significant difference among race (P = 0.023), and serum zinc levels of patients in Europe and America showed the lowest effect. These 2 factors explained 43.83% of the bias. No correlations were identified between serum zinc levels and oral zinc dose (β = −0.066, P = 0.691) or baseline zinc levels (β = −0.048, P = 0.885).

Figure 3.

Metaregression data of serum zinc levels based on (a) serum zinc, (b) oral zinc dose, and (c) intervening time at baseline.

Figure 4.

Forest plot: the effect of zinc supplementation on serum zinc levels in different regions (East Asia, West Asia, and Europe/North America).

3.5. Results of Dose Subgroup

To explore the effects of zinc dose on various outcomes, we performed a dose-special subgroup analysis. The results showed zinc supplement results in higher serum zinc levels and lower CRP and MDA levels, which was consistent with the crude results. However, no dose-effect trend was found when zinc dose changed. In the heterogeneity test, 8 results showed obvious heterogeneity out of a total of 23 (I-squared > 50%, P < 0.1). All data are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of dose subgroup.

| Factor | Zinc dose | Number of studies | Heterogeneity test | Weighted mean difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | I 2 | P value | WMD | [95% CI] | P value | |||

| Serum zinc (ug/dL) | <45 mg | 4 | 2.27 | 27.52% | 0.211 | 30.792 | [23.781, 44.201] | <0.001∗ |

| 45–50 mg | 6 | 121.15 | 95.90% | <0.001 | 23.831 | [4.824, 42.837] | 0.014∗ | |

| >50 mg | 3 | 18.01 | 88.90% | <0.001 | 32.692 | [20.111, 45.273] | <0.001∗ | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.5 mg | 1 | - | - | - | 0.530 | [−3.769, 2.709] | 0.621 |

| ≥90 mg | 2 | 1.16 | 13.70% | 0.282 | 0.124 | [−1.062, 1.309] | 0.838 | |

| nPNA (g/kg/d) | 11 mg | 1 | - | - | - | 0.41 | [0.292, 0.528] | <0.001∗ |

| 45 mg | 2 | 1.3 | 23.00% | 0.250 | 0.019 | [−0.130, 0.167] | 0.805 | |

| Dietary protein intake (g/kg/d) | 45 mg | 2 | 0.64 | 0.00% | 0.425 | 5.605 | [−0.527, 11.736] | 0.073 |

| 50 mg | 2 | 0.53 | 0.00% | 0.467 | 5.373 | [−1.351, 12.097] | 0.117 | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | <50 mg | 2 | 6.96 | 85.60% | 0.008 | 0.37 | [−0.225, 0.966] | 0.223 |

| ≥50 mg | 2 | 2.35 | 57.40% | 0.125 | 0.309 | [−0.343, 0.962] | 0.353 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | <45 mg | 2 | 3.62 | 71.87% | 0.054 | 1.018 | [−0.188, 2.223] | 0.098 |

| ≥45 mg | 2 | 0.08 | 0.00% | 0.780 | 0.385 | [−0.307, 1.078] | 0.275 | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | <50 mg | 2 | 31.35 | 96.80% | <0.001 | 4.083 | [−14.455, 22.621] | 0.666 |

| ≥50 mg | 2 | 10.09 | 96.80% | <0.001 | 0.031 | [−6.494, 6.556] | 0.993 | |

| LDL (mg/dL) | <50 mg | 2 | 4.84 | 79.40% | 0.028 | 6.088 | [−25.371, 37.548] | 0.704 |

| ≥50 mg | 2 | 0.46 | 0.00% | 0.496 | 44.792 | [34.951, 54.632] | <0.001∗ | |

| TC (mg/dL) | ≤50 mg | 2 | 0.03 | 0.00% | 0.857 | 37.045 | [26.472, 47.617] | <0.001∗ |

| >50 mg | 2 | 1.81 | 44.70% | 0.179 | −2.381 | [−19.731, 14.968] | 0.788 | |

| TG (mg/dL) | <50 mg | 2 | 7.67 | 87.00% | 0.006 | 0.337 | [−53.525, 54.200] | 0.99 |

| ≥50 mg | 1 | - | - | - | −3.112 | [−40.718, 34.718] | 0.876 | |

| CRP (ng/mL) | 11 mg | 1 | - | - | - | −5.799 | [−8.925, −2.673] | <0.001∗ |

| 45 mg | 2 | 2.11 | 52.60% | 0.146 | −10.234 | [−20.861, −0.392] | 0.039∗ | |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | <50 mg | 2 | 10.34 | 90.30% | 0.001 | −1.617 | [−2.948, −0.286] | 0.017∗ |

| ≥50 mg | 1 | - | - | - | −0.8 | [−0.995, −0.605] | <0.001∗ | |

Note. -: values could not be calculated due to an insufficient number of studies; ∗P < 0.05, and WMD was considered statistically significant.

3.6. Results of Intervening Time Subgroup

To investigate the effects of intervention time on a series of outcomes, we performed a time-special subgroup analysis. In the results, we found that zinc supplementation induced a time effect in serum zinc levels and dietary protein intake. Although our results showed zinc supplementation results in higher SOD levels and lower CRP and MDA levels in all subanalyses, no time effect was identified. Heterogeneity was lower in the time subgroup compared with results in the crude analysis. Of the 25 results analyzed, 4 showed obvious heterogeneity (I-squared > 50%, P < 0.1). All data are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of intervention time subgroup.

| Factor | Intervention time | Number of studies | Heterogeneity test | Weighted mean difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | I 2 | P value | WMD | [95% CI] | P value | |||

| Serum zinc (ug/dL) | <50 days | 6 | 21.15 | 85.90% | <0.001 | 23.831 | [4.824, 42.837] | 0.014∗ |

| 50–60 days | 4 | 1.82 | 0.00% | 0.402 | 28.310 | [24.399, 32.220] | <0.001∗ | |

| >60 days | 5 | 1.07 | 12.90% | 0.388 | 36.065 | [25.694, 46.437] | <0.001∗ | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 60 days | 2 | 1.16 | 13.70% | 0.282 | 0.124 | [−1.062, 1.309] | 0.838 |

| 90 days | 1 | - | - | - | 0.530 | [−3.769, 2.709] | 0.621 | |

| nPNA (g/kg/d) | <50 days | 2 | 0.58 | 0.00% | 0.447 | −0.018 | [−0.128, 0.092] | 0.751 |

| ≥50 days | 2 | 1.3 | 31.10% | 0.243 | 0.235 | [−0.108, 0.578] | 0.179 | |

| Dietary protein intake (g/kg/d) | <50 days | 2 | 0.18 | 0.00% | 0.776 | 3.322 | [−3.407, 9.407] | 0.359 |

| ≥50 days | 2 | 0.12 | 0.00% | 0.812 | 8.109 | [1.592, 14.408] | <0.001∗ | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | <60 days | 2 | 1.96 | 45.60% | 0.134 | 0.301 | [−0.225, 0.966] | 0.223 |

| ≥60 days | 2 | 2.17 | 47.40% | 0.125 | 0.409 | [−0.243, 1.062] | 0.353 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | <60 days | 2 | 0.04 | 0.00% | 0.850 | 0.378 | [−0.048, 0.804] | 0.082 |

| ≥60 days | 2 | 3.69 | 72.90% | 0.055 | 1.171 | [0.083, 2.259] | 0.035∗ | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | <60 days | 2 | 31.35 | 96.80% | <0.001 | 4.083 | [−14.455, 22.621] | 0.666 |

| ≥60 days | 2 | 10.09 | 90.10% | 0.001 | 0.031 | [−6.494, 6.556] | 0.993 | |

| LDL (mg/dL) | <60 days | 2 | 1.96 | 49.00% | 0.161 | 34.829 | [17.061, 52.597] | <0.001∗ |

| ≥60 days | 2 | 24.46 | 95.90% | <0.001 | 19.971 | [−36.680, 76.623] | 0.490 | |

| TC (mg/dL) | <60 days | 2 | 1.5 | 33.20% | 0.221 | 18.673 | [−2.741, 40.088] | 0.087 |

| ≥60 days | 3 | 22.15 | 91.00% | <0.001 | 11.147 | [−18.788, 41.082] | 0.465 | |

| TG (mg/dL) | <60 days | 1 | - | - | - | 26.080 | [6.602, 45.558] | 0.009 |

| ≥60 days | 2 | 1.01 | 8.60% | 0.317 | −17.415 | [−42.743, 7.913] | 0.178 | |

| CRP (ng/mL) | <60 days | 2 | 2.11 | 14.60% | 0.146 | −10.234 | [−20.861, 0.392] | 0.059 |

| ≥60 days | 1 | - | - | - | −5.799 | [−8.925, −2.673] | <0.001∗ | |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | <60 days | 1 | - | - | - | −2.330 | [−3.048, −1.612] | <0.001∗ |

| ≥60 days | 2 | 0.53 | 0.00% | 0.467 | −0.831 | [−1.007, −0.654] | <0.001∗ | |

| SOD (U/g Hb) | <60 days | 1 | - | - | - | 446.600 | [340.276, 552.924] | <0.001∗ |

| ≥60 days | 1 | - | - | - | 234.200 | [35.906, 432.494] | 0.021∗ | |

Note. -: values could not be calculated due to an insufficient number of studies; ∗P < 0.05, and WMD was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Some dialysis complications, such as malnutrition and inflammation, were partly attributed to zinc deficiency. From previous studies, the conclusions regarding zinc supplementation for MHD patients were not consensus. The effect on nutritional status was one of the most controversial results. Contrary to the majority of opinions and our results, Matson et al. reported that evidence is limited for proving the effects of zinc supplementation on anorexia and nutritional status in MHD patients [12]. An earlier article attributed this discrepancy to age of patients and zinc absorption [28]. Notably, in the study of Matson et al., differences in serum zinc levels were not statistically significant between the treatment and placebo groups. However, in our analysis, we found that zinc supplementation increased serum zinc levels for MHD patients. Our results showed that intervention time and race are two factors that correlated significantly with serum zinc levels, and there is a time-effect but not a dose-effect relationship in zinc supplementation. In the included studies, we found that the median intervention time was 60 days and the median zinc dose was 45 mg/day. In the study of Matson et al., patients received 220 mg zinc sulfate (45 mg elemental zinc) per day for 6 weeks; thus, the limited intervention time may be a possible explanation. It is also plausible that zinc supplementation showed different effects from various racial groups. The mean change of serum zinc levels in the Taiwanese population was several times higher than in the Western regions [8]. European studies showed the lowest effect compared with data from Asia, most likely due to differences in epidemiology and diet. Further studies are warranted to comprehensively investigate the precise effect on different racial groups. Another notable finding was that, although no statistical significance was found in data on albumin and hemoglobin, the P values were close to the significance threshold (albumin: P = 0.061; hemoglobin: P = 0.069). Subgroup analyses also showed a time-effect relationship in the two factors. We assume the long-term effect of zinc supplementation may improve these nutritional indices, but this interpretation also requires further testing. Nonetheless, our results suggest intervention time of zinc supplementation should be adequate when aiming to improve nutritional indices and appetite.

Hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia have been reported in previous studies on zinc-deficient diets, which could induce cardiovascular events and insulin resistance in CKD patients [29, 30]. Although a series of previous studies suggest that zinc supplementation improves blood lipid metabolism, this finding was not drawn from our pooled data. The effects and trends of zinc supplementation on lipid profile were inconsistent and even contradictory in the results [17, 20, 21]. There are several possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, it is possible that the characteristics of included patients were divided. For example, zinc supplementation could increase blood lipids by improving energy intake in patients with anorexia [31] and show an opposite effect when including patients with hyperlipemia or insulin resistance [32–34]. Second, little is known about lipid intake from the included studies; diverse dietary lipid intake may have led to information bias. Therefore, more evidence is needed to determine the effects of zinc supplementation on lipid profile in MHD patients.

Inflammation and oxidative stress are common complications in MHD patients. Several previous studies have found that zinc deficiency in MHD patients may result in increased oxidative stress and CRP concentrations [22, 35]. The antioxidative action of zinc involves 2 mechanisms: (1) directly protecting easily oxidized groups such as sulfhydryl and (2) producing some other ultimate long-term antioxidant like metallothionein [36, 37]. Zinc could also decrease CRP and other inflammatory cytokines through increased antioxidant power; the major target is most likely the NF-kappa b pathway [38, 39]. In our analysis, all the included studies showed that zinc supplementation was positive for anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity. The pooled results showed statistical significance in all subgroups, and no significance for time or dose effect was observed. This may suggest that zinc supplementation may lead to an anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effect in MHD patients.

It should be noted that there might be some possible limitations in our meta-analysis. First, adverse outcomes of zinc supplementation were not analyzed. As is known, although zinc is an essential requirement for good health, an excess in zinc supplementation can be harmful. Excessive absorption of zinc can suppress copper and iron absorption and may cause nerve damage [40, 41]. In the included studies, only one paper mentioned asking patients whether they had experienced any adverse effects. No side effects could be analyzed in the pooled data; incomplete data may have deterred this evaluation. Second, due to insufficient data, the effects of zinc supplementation on clinical endpoint events, such as cardiovascular events or death, remain unclear. Such discrepancies make it difficult to attain strong evidence for MHD patients. Finally, the epidemiology varies significantly across the different regions. For example, zinc deficiency is widespread in East Asia (nearly 40% to 60% of the population have mild or moderate zinc deficiency); the proportion is much lower in Europe and America [42, 43]. However, meta-analyses of the racial subgroups could not be performed due to lack of data in most outcomes. This may have generated a selection bias in our results.

5. Conclusion

Our meta-analysis suggests that zinc supplementation benefits the nutritional status of MHD patients and shows a time-effect relationship. It also leads to an anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effect in MHD patients. Still, there is a need for more evidence regarding the effects on lipid profile. Given the presence of data deficiency in this study, further studies are warranted to comprehensively investigate the effects of zinc supplementation on clinical endpoint events and on race.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (nos. 81473621, 81673920, and 81373570), the Southern Medical University Scientific Research Foundation (no. CX2015N003), the Traditional Chinese Medicine Project of Guangdong Province (no. 20151300), and the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201705030006).

Contributor Information

Shao-Xiang Xian, Email: shaoxiangx@hotmail.com.

Lu Lu, Email: coinland@gzucm.edu.cn.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence this work; there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service, and company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in this manuscript.

Authors' Contributions

Ling-Jun Wang, Ming-Qing Wang, and Rong Hu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Imanishi M., Hori Y., Nagaoka M., Sugiura Y. Design of novel zinc finger proteins: Towards artificial control of specific gene expression. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2001;13(1):91–97. doi: 10.1016/S0928-0987(00)00212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alirezaei M., Mordelet E., Rouach N., Nairn A. C., Glowinski J., Prémont J. Zinc-induced inhibition of protein synthesis and reduction of connexin-43 expression and intercellular communication in mouse cortical astrocytes. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;16(6):1037–1044. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibs K. H., Rink L. Zinc-altered immune function. The Journal of Nutrition. 2003;133:1452S–1456S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1452S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dashti-Khavidaki S., Khalili H., Vahedi S.-M., Lessan-Pezeshki M. Serum zinc concentrations in patients on maintenance hemodialysis and its relationship with anemia, parathyroid hormone concentrations and pruritus severity. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 2010;21(4):641–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muirhead N., Kertesz A., Flanagan P. R., Hodsman A. B., Hollomby D. J., Valberg L. S. Zinc metabolism in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. American Journal of Nephrology. 1986;6(6):422–426. doi: 10.1159/000167247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez C., Aranda P., Perez de la Cruz A., Llopis J. Magnesium and zinc status in patients with chronic renal failure: influence of a nutritional intervention. Magnesium Research. 2009;22:72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimmel P. L., Langman C. B., Bognar B., et al. Zinc nutritional status modifies renal osteodystrophy in uremic rats. Clinical Nephrology. 2001;56:445–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo C.-H., Wang C.-L. Effects of zinc supplementation on plasma copper/zinc ratios, oxidative stress, and immunological status in hemodialysis patients. International Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013;10(1):79–89. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turk S., Bozfakioglu S., Ecder S. T., et al. Effects of zinc supplementation on the immune system and on antibody response to multivalent influenza vaccine in hemodialysis patients. The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 1998;21:274–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahni N., Gupta K. L., Rana S. V., Prasad R., Bhalla A. K. Intake of antioxidants and their status in chronic kidney disease patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2012;22(4):389–399. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger M. M., Shenkin A., Revelly J.-P., et al. Copper, selenium, zinc, and thiamine balances during continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration in critically ill patients. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;80(2):410–416. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matson A., Wright M., Oliver A., et al. Zinc supplementation at conventional doses does not improve the disturbance of taste perception in hemodialysis patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2003;13(3):224–228. doi: 10.1016/S1051-2276(03)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keast R. S. J., Canty T. M., Breslin P. A. S. Oral zinc sulfate solutions inhibit sweet taste perception. Chemical Senses. 2004;29(6):513–521. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins J. P. T., Altman D. G., Gøtzsche P. C., et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. British Medical Journal. 2011;343(7829) doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi H., Abe M., Okada K., et al. Oral zinc supplementation reduces the erythropoietin responsiveness index in patients on hemodialysis. Nutrients. 2015;7(5):3783–3795. doi: 10.3390/nu7053783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Shazly A. N., Ibrahim S. A. E.-H., El-Mashad G. M., Sabry J. H., Sherbini N. S. Effect of zinc supplementation on body mass index and serum levels of zinc and leptin in pediatric hemodialysis patients. International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease. 2015;8:159–163. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S94923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Argani H., Mahdavi R., Ghorbani-haghjo A., Razzaghi R., Nikniaz L., Gaemmaghami S. J. Effects of zinc supplementation on serum zinc and leptin levels, BMI, and body composition in hemodialysis patients. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 2014;28(1):35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pakfetrat M., Shahroodi J. R., Zolgadr A. A., Larie H. A., Nikoo M. H., Malekmakan L. Effects of zinc supplement on plasma homocysteine level in end-stage renal disease patients: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Biological Trace Element Research. 2013;153(1-3):11–15. doi: 10.1007/s12011-013-9639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazani M., Argani H., Rashtchizadeh N., et al. Effects of Zinc Supplementation on Antioxidant Status and Lipid Peroxidation in Hemodialysis Patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2013;23(3):180–184. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahimi-Ardabili B., Argani H., Ghorbanihaghjo A., et al. Paraoxonase enzyme activity is enhanced by zinc supplementation in hemodialysis patients. Renal Failure. 2012;34(9):1123–1128. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.717479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roozbeh J., Hedayati P., Sagheb M. M., et al. Effect of zinc supplementation on triglyceride, cholesterol, LDL, and HDL levels in zinc-deficient hemodialysis patients. Renal Failure. 2009;31(9):798–801. doi: 10.3109/08860220903216055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rashidi A. A., Salehi M., Piroozmand A., Sagheb M. M. Effects of Zinc Supplementation on Serum Zinc and C-Reactive Protein Concentrations in Hemodialysis Patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2009;19(6):475–478. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nava-Hernandez J., Amato D. Effect of zinc supplements on the levels of pre-albumin and transferrin in patients with dialysis. Revista de Investigación Clínica. 2005;57:123–125. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chevalier C. A., Liepa G., Murphy M. D., et al. The effects of zinc supplementation on serum zinc and cholesterol concentrations in hemodialysis patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2002;12(3):183–189. doi: 10.1053/jren.2002.33515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Candan F., Gültekin F., Candan F. Effect of vitamin C and zinc on osmotic fragility and lipid peroxidation in zinc-deficient haemodialysis patients. Cell Biochemistry & Function. 2002;20(2):95–98. doi: 10.1002/cbf.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jern N. A., VanBeber A. D., Gorman M. A., Weber C. G., Liepa G. U., Cochran C. C. The effects of zinc supplementation on serum zinc concentration and protein catabolic rate in hemodialysis patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2000;10(3):148–153. doi: 10.1053/jren.2000.7413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brodersen H.-P., Holtkamp W., Larbig D., et al. Zinc supplementation and hepatitis B vaccination in chronic haemodialysis patients: A multicentre study. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation . 1995;10(9):p. 1780. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a091426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart-Knox B. J., Simpson E. E. A., Parr H., et al. Zinc status and taste acuity in older Europeans: the ZENITH study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;59(supplement 2):S31–S36. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalkan Ucar S., Coker M., Sözmen E., Goksen Simsek D., Darcan S. An association among iron, copper, zinc, and selenium, and antioxidative status in dyslipidemic pediatric patients with glycogen storage disease types IA and III. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 2010;24(1):42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lobo J. C., Torres J. P. M., Fouque D., Mafra D. Zinc deficiency in chronic kidney disease: Is there a relationship with adipose tissue and atherosclerosis? Biological Trace Element Research. 2010;135(1-3):16–21. doi: 10.1007/s12011-009-8504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki H., Asakawa A., Li J. B., et al. Zinc as an appetite stimulator - The possible role of zinc in the progression of diseases such as cachexia and sarcopenia. Recent Patents on Food, Nutrition & Agriculture. 2011;3(3):226–231. doi: 10.2174/2212798411103030226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He B. P., Li D. F., Ma J. W., et al. Determination of trace copper and zinc in hypertension complicated with hyperlipemia by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Guang Pu Xue Yu Guang Pu Fen Xi. 2004;24:741–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogalska J., Brzóska M. M., Roszczenko A., Moniuszko-Jakoniuk J. Enhanced zinc consumption prevents cadmium-induced alterations in lipid metabolism in male rats. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2009;177(2):142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen H., MacDonald R., Bruemmer D., et al. Zinc deficiency alters lipid metabolism in LDL receptor-deficient mice treated with rosiglitazone. Journal of Nutrition. 2007;137(11):2339–2345. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobo J. C., Stockler-Pinto M. B., Farage N. E., et al. Reduced plasma zinc levels, lipid peroxidation, and inflammation biomarkers levels in hemodialysis patients: Implications to cardiovascular mortality. Renal Failure. 2013;35(5):680–685. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2013.789960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu K., Nie S., Li C., et al. Antidiabetic and pancreas-protective effects of zinc threoninate chelate in diabetic rats may be associated with its antioxidative stress ability. Biological Trace Element Research. 2013;153(1-3):291–298. doi: 10.1007/s12011-013-9675-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malhotra A., Dhawan D. K. Zinc improves antioxidative enzymes in red blood cells and hematology in lithium-treated rats. Nutrition Research. 2008;28(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saad A. A., Doka Y. A., Osman S. M., Magzoub M., Ali N. I., Adam I. Zinc, copper and C-reactive protein in children with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria in an area of unstable malaria transmission in eastern Sudan. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2013;59(2):150–153. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fms056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bao B., Prasad A. S., Beck F. W. J., et al. Zinc decreases C-reactive protein, lipid peroxidation, and inflammatory cytokines in elderly subjects: a potential implication of zinc as an atheroprotective agent. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;91(6):1634–1641. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson A. R., Munoz A., Gottlieb J. L., Jarrard D. F. High dose zinc increases hospital admissions due to genitourinary complications. The Journal of Urology. 2007;177(2):639–643. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Denderen J. C. M., Van Wieringen G. W., Hillen B., Bleys R. L. A. W. Zinc sulphate-induced anosmia decreases the nerve fibre density in the anterior cerebral artery of the rat. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2001;94(1-2):102–108. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00354-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wessells K. R., Brown K. H. Estimating the global prevalence of zinc deficiency: results based on zinc availability in national food supplies and the prevalence of stunting. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050568.e50568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghasemi A., Zahediasl S., Hosseini-Esfahani F., Azizi F. Reference values for serum zinc concentration and prevalence of zinc deficiency in adult iranian subjects. Biological Trace Element Research. 2012;149(3):307–314. doi: 10.1007/s12011-012-9445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]