Abstract

Every spring a huge number of passerines cross the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea on their way to their breeding grounds. Stopover sites after such extended barriers where birds can rest, refuel, and find shelter from adverse weather, are of crucial importance for the outcome of their migration. Stopover habitat selection used by migrating birds depends on landscape context, habitat patch characteristics, as well as on the particular energetic conditions and needs of individual birds, but it is still poorly investigated. We focused on a long-distance migrating passerine, the woodchat shrike, in order to investigate for the first time the species’ habitat selection at a spring stopover site (island of Antikythira, Greece) after the crossing of the Sahara Desert and Mediterranean Sea. We implemented radio-tracking, color-ringing, and visual behavioral observations to collect data on microhabitat use. Generalized Linear Mixed Models were developed to identify the species’ most preferred microhabitat during its stopover on this low human disturbed island. We found that high maquis vegetation surrounded by low vegetation was chosen as perches for hunting. Moreover, high maquis vegetation appeared to facilitate hunting attempts toward the ground, the most frequently observed foraging strategy. Finally, we discuss our findings in the context of conservation practices for the woodchat shrike and their stopover sites on Mediterranean islands.

Keywords: habitat selection, Mediterranean ecosystem, radio-tracking, stopover ecology, woodchat shrike Lanius senator.

Every year on their way to their breeding or wintering grounds, long distance migrants face huge ecological barriers, such as the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea (Newton 2008). During spring migration, large and small islands scattered in the Mediterranean Sea provide stopover opportunities (Spina et al. 2006) for long distance migrants (of the European–African bird migration system), where they can rest or/and refuel before resuming migratory flights. According to the optimal migration theory, birds are expected to “optimally” modulate their travel cost in relation to time, energy, and safety (Alerstam and Lindström 1990). The vast majority of time spent during migration comprises stopover rather than actual migratory flights (Hedenström and Alerstam 1997; Wikelski et al. 2003; Bowlin et al. 2005), rendering habitat use and availability at stopover sites a key component of the migratory process (Zduniak and Yosef 2011; Zduniak and Yosef 2012).

Carryover effects play a crucial role in the ecology of migratory animals (Harrison et al. 2011), because their populations are influenced by the interaction of events occurring in different geographic regions at different stages of their annual cycle (Powell et al. 2015; Rushing et al. 2016). In this context, the choices migrants make at their stopover sites have been shown to strongly influence the rate of mass gain (Bairlein 1985; Delingat et al. 2006; Schaub et al. 2008), which in turn can affect the timing of migration (Smith and Moore 2003) and, later on, their reproductive success (Sandberg and Moore 1996; Drent et al. 2003), and their survival during the stationary non-breeding season (Pfister et al. 1998). Migrants have to make optimal use of the ecosystems at their stopover sites to maximize their fuel deposition, as well as to avoid predators (Alerstam 2011). Hence, migrants are expected to assess these factors and adopt the most efficient foraging strategy (McCabe and Olsen 2015), although this may not always be the case. Thus, management practices at stopover sites are important for the conservation of migratory species, such as the woodchat shrike (Yosef et al. 2006; Tøttrup et al. 2008).

To remain within their migratory schedules, birds have to choose among unfamiliar habitats to rest, refuel, and find shelter from predators (Lindstrom and Alerstam 1992). Therefore, habitat use of migrants is expected to be non-random. Indeed, habitat selection occurs just after landfall and is likely to be based mainly on visual cues (Chernetsov 2012). Still, sound cues may also be important for migrants, as landfall can be induced using playback, even in suboptimal habitats (Mukhin et al. 2008). In general, habitat selection during migration is thought to be controlled by endogenous preferences and the functional morphology of the birds (Bairlein 1983), their foraging strategy and the spatial distribution of food resources (Hutto 1985a, 1985b; Martin and Karr 1986; Chernetsov 1998; Titov 2000), intraspecific competition (Hutto 1985a), and predation risk (Lank and Ydenberg 2003; Sapir et al. 2004; Chernetsov 2012).

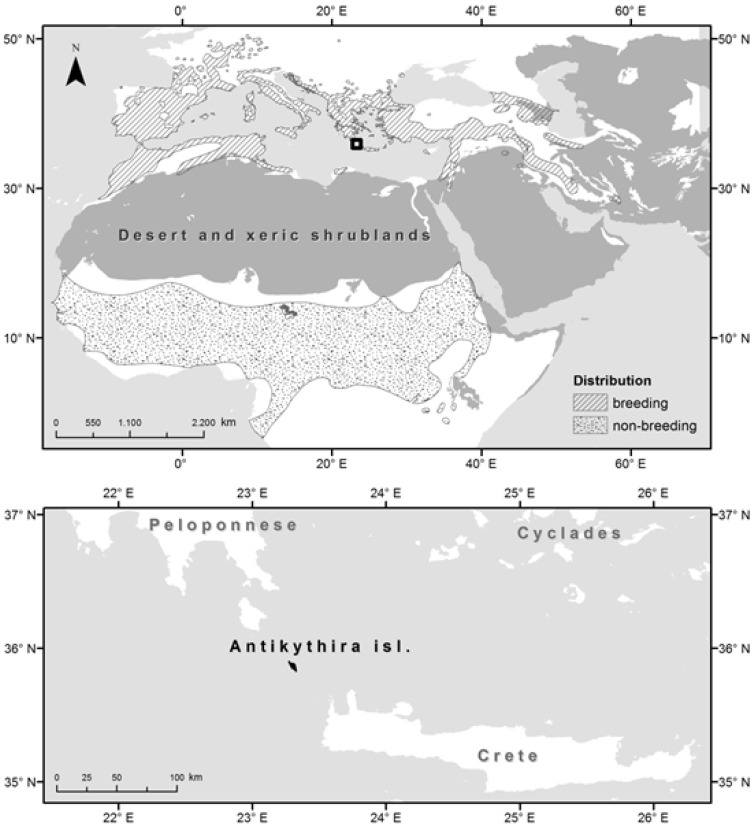

The woodchat shrike Lanius senator is a medium-sized passerine whose populations are currently declining (BirdLife International and Nature Serve 2015). To date, there are only a few studies on the species’ ecology, mainly focusing on its breeding grounds. Woodchat shrikes breed in most of the countries around the Mediterranean Sea and winter in sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 1). During the breeding season, woodchat shrikes generally prefer semi-open areas with well-spaced trees, such as open woodlands, old orchards, olive groves, gardens, and parks (Yosef 2008). This bird species mostly preys on insects, like Orthoptera or Coleoptera but also on small vertebrates like geckos or even small passerines (Isenmann and Fradet 1998; Sandor et al. 2004). Furthermore, similar to other shrikes, the woodchat shrike can be characterized as a sit-and-wait predator (Yosef et al. 2012). On their northbound journey, many woodchat shrikes stopover for refueling at the Mediterranean islands (Pilastro et al. 1998, Gargallo et al. 2011) that are characterized as xeric ecosystems (Katsimanis et al. 2006) because they are mainly covered by shrublands. The Mediterranean vegetation type consists of 2 main formations (Blondel and Aronson 1999): the maquis (taller, evergreen sclerophyllous formations) and phrygana (seasonally dimorphic, drought-deciduous formations).

Figure 1.

The location of the study area, the island of Antikythira, in relation to the 2 ecological barriers, the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea, that the migrating woodchat shrikes cross during spring migration. The distribution map of the woodchat shrike is also exhibited (BirdLife International and NatureServe 2015).

In this study, we investigated microhabitat use by the woodchat shrike during their spring passage from a small Greek island (Antikythira), just after the crossing of 2 ecological barriers in the Palearctic system, the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea (Figure 1), by means of radio-tracking and visual observations of color-ringed birds and random (non-tagged) individuals. Antikythira Island is used only as a stopover site by woodchat shrikes, whereas the species also breeds in many Mediterranean islands (BirdLife International and Nature Serve 2015). Based on the species’ biology, we hypothesized that woodchat shrikes prefer relatively high perches (e.g., maquis), which provide them with satisfactory visibility, in order to be able to detect at the same time potential prey, dwelling at the ground or flying, as well as present predators (e.g., raptors) (Yosef 1993; Yosef and Grubb 1993; Yosef and Grubb 1994). To this end, we also examined whether habitat use is associated with particular foraging behavior (hunting, consuming, and scanning the surrounding area for prey), and hunting direction.

Materials and Methods

Study site

This study was conducted on the island of Antikythira (35°51'N, 23°18'E), Greece. This small island has an area ca. 20 km2 and is located 31.5 km southeast from the island of Kythira and at an equal distance northwest of Crete (Figure 1). The anthropogenic disturbance is moderate as the island currently has few inhabitants (approximately 25). Thus, agricultural practices are relatively few and declining. The local flora has adapted, recolonizing abandoned terraces and enveloping the rocky inclines (Palmer et al. 2010). Hence, the current land cover on the island mostly consists of phrygana (61%), followed by maquis (25%), and to a lesser extent of abandoned cultivations (4%), vegetated sea cliffs (8%), whereas settlements cover less than 1% of the island (data retrieved from the 3rd National Report for the Habitats Directive; Panitsa M, personal communication).

Capture and marking of individuals

Woodchat shrikes were trapped with mist nets during spring 2015 at the Antikythira Bird Observatory in the framework of the standardized program for bird ringing of migratory birds run by the Hellenic Ornithological Society and the Hellenic Bird Ringing Centre, which has been conducted annually from the end of March until the end of May since 2007. Trapping and ringing took place from 7 AM to 1 PM using 11 mist nets at fixed locations in the center of the island. Trapped birds were aged and sexed according to Svensson (1992). All trapped woodchat shrikes were marked with aluminum rings and an individual combination of 3 color rings (hereafter ID). Five of them were also fitted with light-weight radio transmitters (model NTQB-1; Lotek wireless Inc., Canada) using a leg-loop harness (Rappole and Tipton 1991). The length of the leg-loop harness was estimated according to Naef-Daenzer (2007). The mass of the transmitters and the harness did not exceed the 5% of bird’s body mass. The transmitters had a minimum lifespan of 3 weeks. A hand held receiver (model: SRX800 m-2; Lotek wireless Inc., Canada) and a 3 element Yagi antenna (Biotrack Ltd., UK) were used for radio-tracking.

Radio- and color-tagged birds were released immediately after tagging at their capture location.

Tracking of color- and radio-tagged birds

Tracking of tagged birds took place between sunrise and twilight during the study period. The minimum interval between 2 successive fixes of a single bird was 30 min in order to increase the independence of observations (White and Garrott 1990; Chernetsov and Mukhin 2006). Birds were assumed to have resumed their northbound journey if they remained undetected for at least 3 consecutive days after last contact. Regarding radio-tagged birds, direct observations throughout their stopover provided no indication that the transmitters were altering their behavior. In particular, radio-tagged birds were commonly observed foraging normally and no birds were seen attempting to pull off their transmitter (Seewagen et al. 2010). As far as color-tagged birds are concerned, ringing is a widely used method that does not alter behavior. However, it was within 30 min upon handling that radio-tagged birds were preening more than usually but afterwards, their behavior was not influenced (Papageorgiou D, unpublished data). Therefore, the first localization included in the subsequent analyses took place at least 1 h after release.

Radio-tagged birds’ localization was determined by homing (White and Garrott 1990), and birds were approached to no less than a 15 m distance to avoid disturbance. Regarding color-tagged birds, the entire island was searched on a daily basis, starting from the ringing area. As soon as a colored-tagged individual was observed, it was tracked continuously until it was lost out of sight. If birds were tracked up until the sunset, we visited the last localization site of the focal bird on the next day (between 6 and 6:20 AM) to resume the tracking session; in most cases, these birds were encountered at the same roosting tree/bush. The position of both radio- and color-tagged birds was always confirmed visually. Localizations were recorded with an Android tablet using the Locus Maps Free application (Locus 2014) and a digitized map of the island. Throughout the study period, 1 or 2 observers were in the field, depending on the number of tagged birds that were to be tracked.

Microhabitat use

Microhabitat use was investigated by recording and comparing habitat characteristics (Table 1) for those birds that had more than 14 localizations (either using radio-tracking or visual observations of birds with color rings) between visited and non-visited areas within their 100% Minimum Convex Polygon (MCP). In particular, we contrasted the habitat coverage (percentage of vegetation types) between 2 m × 2 m squares centered on each occurrence point (hereafter visited squares) and 2 m × 2 m squares centered on random locations (hereafter non-visited squares). The choice of a 4 m2 plot was based on a preliminary mapping of the study area in combination with observations concerning the behavior of the woodchat shrike at the island of Antikythira. This species mostly sits on the outer branches of the used plant (tree or bush) and scans the ground only in a short distance next to it. Thus, we consider that this plot size is representative of the microhabitat that woodchat shrikes use as perch to explore its surroundings.

Table 1.

Habitat categories that were considered as candidate explanatory variables of microhabitat use by the woodchat shrike

| Code | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| LG | Low Grass and herbal vegetation | Grass and herbal vegetation of mean height < 30 cm |

| HGr | Heigh Grass and herbal vegetation | Grass and herbal vegetation of mean height > 30 cm |

| LPh | Low Phrygana | Low woody vegetation cover, dominated by spaced, spiny and aromatic cushion-shaped shrubs. Mean height < 0.4 m. |

| HPh | High Phrygana | Woody vegetation cover, dominated by spaced, spiny and aromatic cushion-shaped shrubs. Mean height 0.4− 0.8 m |

| LMa | Low Maquis | Evergreen, sclerophyllous shrubs and trees of mean height of < 0.8 m |

| MMa | Medium Maquis | Evergreen, sclerophyllous shrubs and trees of mean height of 0.8–1.5 m |

| HMa | High Maquis | Evergreen, sclerophyllous shrubs and trees of mean height of > 1.5 m |

| BG | Bare ground | No vegetation coverage |

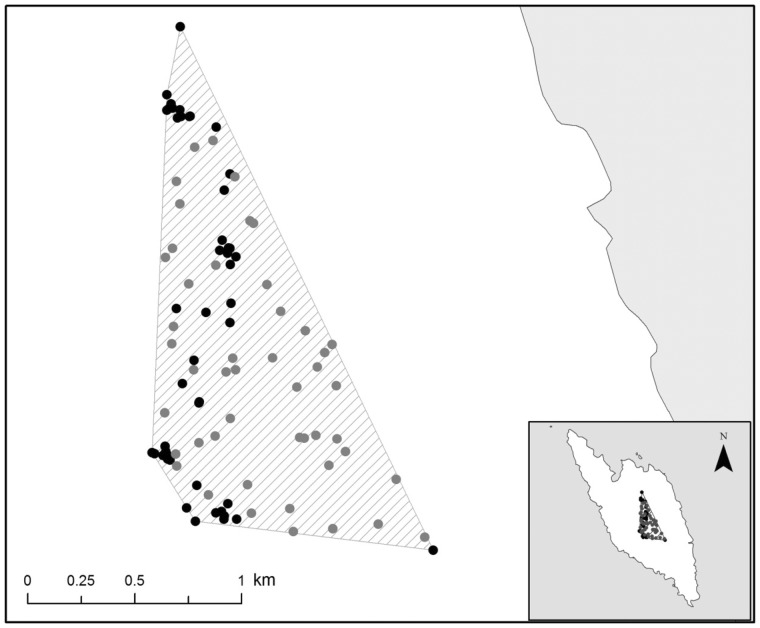

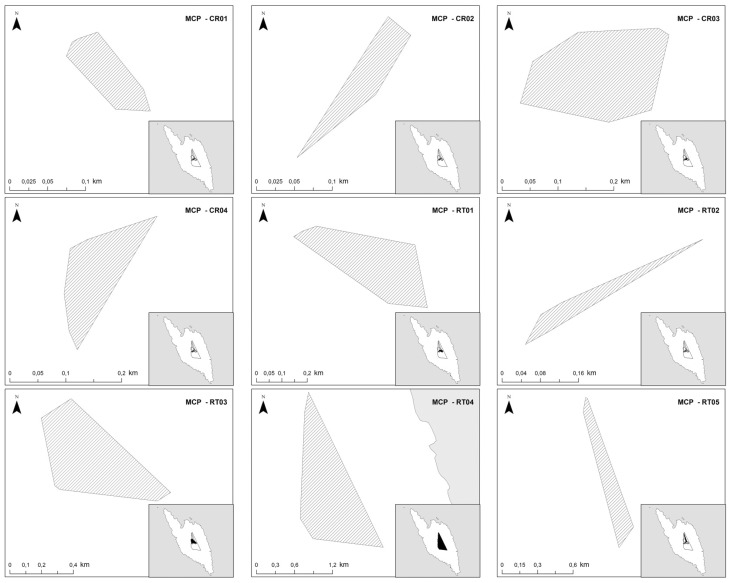

Random locations, equal to the number of the localizations of each bird, were selected within its 100% MCP, located at least 2 m from each other and at least 5 m from the occurrence points (Figure 2). MCPs were delineated in Arc GIS 10.1 (ESRI 2012; Appendix Figure A). Given that woodchat shrikes pause their migratory flights and they remain on this island for very few days and the fact that each localization was taking place every 30 min, we herein considered birds with more than 14 localizations, in order not to miss out those birds that stayed over only for 1 day. In several studies on bats, which can also be radio-tracked only for a restricted time (only 1 to 6 nights) the MCPs were also estimated based on a limited number of localizations (e.g., more than 7) (Russo et al. 2002; Flaquer et al. 2008). The habitat coverage of all squares was mapped and classified to 8 habitat categories (Table 1). Additionally, the plant taxon used by the birds was recorded. Habitat mapping at the visited squares was carried out upon localization of each bird, whereas habitat mapping at the non-visited squares took place when all tagged birds had resumed their migration, that is, from 15–21 May.

Figure 2.

Graphic illustration of the spatial distribution of random points (gray circles) in relation to the occurrence points (dark circles), within the 100% MCP (hashed area) for Tag Id RT04.

To determine which vegetation types were preferred or avoided by woodchat shrikes, habitat characteristics of the visited and non-visited squares were compared using Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) with a binomial error distribution and a logit link function, incorporating both fixed (i.e., the percentage of each habitat category) and random effects (i.e., the birds’ ID) via maximum likelihood. Data exploration indicated that all habitat categories, except for High Grass, High Maquis, and Low Phrygana, differed significantly among birds (Kruskal–Wallis’ tests, P < 0.05); thus, the inclusion of the identity of the tagged birds as a random term to the GLMMs accounted for any individual differences in habitat use (Arlettaz et al. 2012; Patthey et al. 2012). On the other hand, the percentage of habitat categories in the visited squares did not differ significantly between age classes, sex, or tracking technique (radio transmitters or color rings; Kruskal–Wallis’ tests, P > 0.05). Thus we did not consider these factors to influence microhabitat use; consequently, they were not included in our GLMMs.

GLMMs were built using a forward stepwise process, after a modification for variable inclusion developed by Engler et al. (2004). More specifically, this process consists of adding sequentially variables (i.e., the habitat categories) and their quadratic terms if statistically significant, to a null model based on how much reduction in residual deviance they cause (i.e., the variable with the largest residual deviance enters the model first). The process is repeated until all statistically significant variables enter the model. In the final step, all possible pairs of interactions among the selected variables are tested and those that are statistically significant enter the model, too. All models built during each step of the process were then evaluated according to the Akaike Information Criterion (Akaike 1974) and Akaike weight (Burnham and Anderson (2002), corrected for the sample size. Given the lack of multicollinearity (i.e., Spearman’s correlation coefficient r < 0.7), all habitat categories were considered in the model-building process.

Visual observations on habitat use

Preliminary analysis of the data gathered by behavioral observations of random woodchat shrikes indicated that habitat use was related to foraging strategy, because birds allocated plenty of their time looking for prey and refueling. Hence, in order to interpret microhabitat use, foraging and anti-predator behavior (i.e., avoidance of raptors, the only predators preying on woodchat shrikes during the stopover of the latter on the island of Antikythira) were recorded by applying the instantaneous scan sampling method (Altmann 1974). In particular, every 5 min the observer scanned a circular area (of 20 m radius) around them to detect any random woodchat shrikes that were either foraging or looking for shelter in presence of predator. Foraging was divided in 3 sub-classes (hunting, consuming prey and scanning for prey). The focal bird’s foraging behavior was regarded as “hunting” when the bird was making a hunting attempt, as “consuming prey” when it was handling a caught prey and as “scanning for prey” when the focal bird was standing on a perch observing a potential moving prey. When a bird was making hunting attempts, hunting directions were also recorded and were classified in 3 categories (toward the ground, upwards, and hunting attempts at same height level). Behavior in the presence of predator was also recorded. Observations were conducted from sunrise till dusk and the used plant taxon was always noted. Observations were recorded with an Android tablet using the Cyber Tracker application (CyberTracker Conservation 2013).

GLMMs were fitted using the glmer function of the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in R.3.2.2 (Team RC 2015). Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc\. 2014) and R.3.2.2 (Team RC 2015). Statistical significance level set to α = 0.05.

Results

Tracking and habitat use

In total, 41 woodchat shrikes were captured and color ringed between 8 April and 17 May. Five of them were also radio-tagged (Table 2). For the microhabitat use analysis, all 5 radio-tagged birds but only 4 color-ringed birds were used, due to the limited data collected from the rest of the color-ringed birds, totaling 9 individuals. Although our sample size is relatively small, it is supported by other avian studies investigating habitat use (Arlettaz et al. 2012). In total, we obtained 274 locations which correspond to 30.44 ± 17.10 (mean ± standard deviation (SD)) locations per bird (Table 3).

Table 2.

The number of radio- or color-tagged birds, according to age and sex and also the median date of capture for the 41 woodchat shrikes which were ringed during spring 2015 on the island of Antikythira

| Sex/age | Male |

Female |

Total |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | all | ||

| Number of birds | Radio-tagged birds | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Color-ringed birds* | 6 (0) | 11 (3) | 10 (1) | 9 (0) | 16 (1) | 20 (3) | 36 (4) | |

| Median date of capture | Radio-tagged birds | 20 April | ||||||

| Color-ringed birds* | 20 April (18 April) | |||||||

Age class “6” refers to birds that were hatched before last calendar year, but the exact year remains unknown. Age class “5” refers to birds that were definitely hatched during previous calendar year (e.g., first years in early spring; European Union for Bird Ringing (EURING) age codes).

in parenthesis: number of color-ringed birds used in microhabitat use analysis.

Table 3.

Synopsis of tracking activities carried out in spring 2015 (maximum of cumulative distance (km): daily of cumulative distance covered by the bird, MSD: minimum stopover duration, MCP 100%: 100% MCP of each individual in hectares)

| Bird ID | Date of tagging | Age | Sex | Body mass (g) | MSD | Number of localizations | Max of cumulative distance (km) | MCP 100% (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR01 | 21 April 2015 | 6 | M | 32.5 | 6 | 27 | 0.98 | 0.45 |

| CR02 | 7 May 2015 | 5 | F | 31.7 | 4 | 25 | 0.76 | 0.52 |

| CR03 | 22 April 2015 | 6 | M | 28.7 | 4 | 14 | 1.15 | 2.67 |

| CR04 | 10 May 2015 | 6 | M | 29.7 | 4 | 16 | 1.29 | 1.36 |

| RT01 | 14 April 2015 | 6 | M | 29.7 | 11 | 60 | 4.87 | 7.07 |

| RT02 | 18 April 2015 | 6 | M | 34.2 | 1 | 15 | 0.47 | 0.76 |

| RT03 | 20 April 2015 | 6 | M | 29.7 | 8 | 49 | 3.42 | 22.36 |

| RT04 | 3 May 2015 | 5 | F | 31.1 | 4 | 47 | 6.98 | 124.91 |

| RT05 | 7 May 2015 | 5 | F | 32.7 | 1 | 21 | 1.65 | 11.36 |

| Average | 31.11 | 4.78 | 30.44 | 2.40 | 19.05 | |||

| SD | 1.81 | 3.19 | 17.10 | 2.23 | 40.35 |

For age classes see, Table 2.

Most habitat categories (except High Grass, Low Maquis, and Medium Maquis) differed significantly between visited and non-visited squares (Mann–Whitney U-tests, P < 0.05). As mentioned above, during the preliminary phase of data analysis, we investigated whether the tracking technique (i.e., radio-tracking versus color-ringing) influenced the outcome of the GLMM. Given the lack of such an effect, we pooled the data for the analyses presented herein.

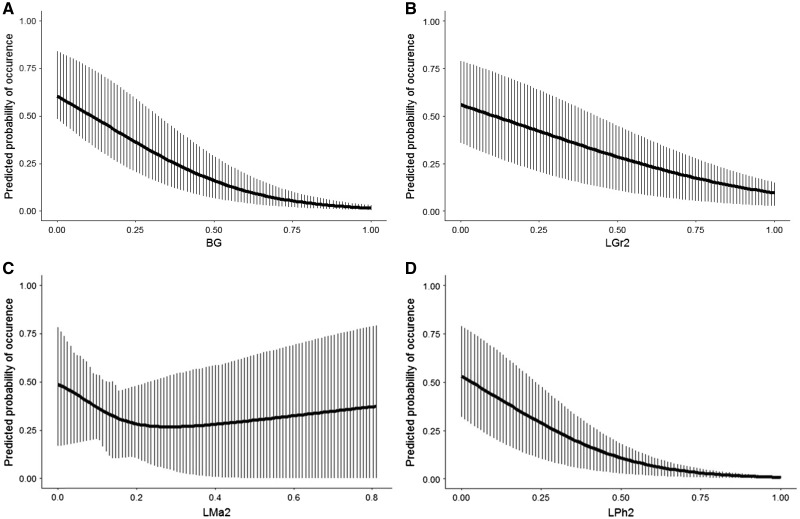

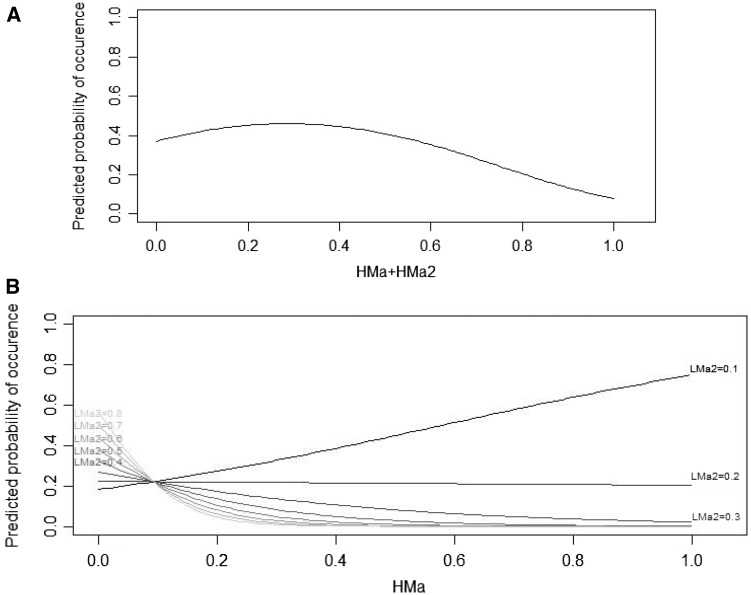

Among all candidate models, only one clearly outperformed other models (i.e., ΔAICc > 2; Appendix Table A). It received substantial support from the data as it had a 77% likelihood of being the best model in the set of models considered (model 57: R2 = 0.48 and AICc = 549.7). According to this model, woodchat shrikes seem to prefer microhabitats which combine a medium percentage of high vegetation (i.e., High Maquis) with a low percentage of low vegetation (i.e., Bare Ground, Low Grass, Low Phrygana, Low Maquis; Table 4; Figures 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Estimated coefficients and standard errors (SE) for the variables of the most parsimonious GLMM model (model 57) on habitat selection by woodchat shrikes on the island of Antikythira, spring 2015

| Parameter | Estimate | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.43 | 0.21 |

| HMa | 5.3 | 1.24 |

| BG | −5.10 | 0.9 |

| LGr2 | 3.05 | 0.66 |

| LPh2 | −5.63 | 1.84 |

| LMa2 | 2.52 | 0.98 |

| HMa2 | −4.53 | 1.45 |

| HMa:LMa2 | −27.07 | 11.58 |

Vegetation type abbreviations same as in Table 1.

Figure 3.

The effect of 4 of the habitat categories included in the final GLMM model describing microhabitat use by the 9 focal woodchat shrikes illustrated as the average marginal predicted probability of occurrence across the range of observed percentage cover of each habitat category. (A). Bare ground (BG). (B). Quadratic term of low grass and herbal vegetation (LGr). (C). Quadratic term of Low Maquis (LMa). (D). Quadratic term of Low Phrygana (LPh). Vertical bars indicate the lower (25%) and upper (75%) quartiles of the predicted values.

Figure 4.

(A) The effect of High Maquis (HMa) and its quadratic term included in the final GLMM describing microhabitat use by the 9 focal woodchat shrikes illustrated as the average marginal predicted probability of occurrence across the range of observed percentage cover. (B). The effect of the interaction between High Maquis (HMa) and the quadratic term of Low Maquis (LMa) included in the final GLMM, describing microhabitat use by the 9 focal woodchat shrikes, illustrated as the average marginal predicted probability of occurrence across the range of observed percentage cover. Each curve represents the predicted probability of occurrence according to the percentages of high maquis vegetation cover for specific values (from 0.1 to 0.8 with 0.1 steps) of Low Maquis’ quadratic terms.

Behavioral observations on habitat use

Concerning the behavior of random individuals, we recorded 522 cases of foraging behavior. On such occasions, the birds allocated their time unevenly among activities related to foraging (G-test, G = 471.23, df = 2, P < 0.05). In particular, hunting (57.37%) was the most commonly observed behavior, followed by scanning for prey (39.81%), and far less frequently by prey consumption (2.81%). Hunting directions were also not random (G-test, G = 193.65, df = 2, P < 0.05). The vast majority of hunting directions were toward the ground (85.3%). On the contrary, only in a few occasions the birds were observed hunting a prey at the same level as their standing point (10.20%) or upwards (4.48%).

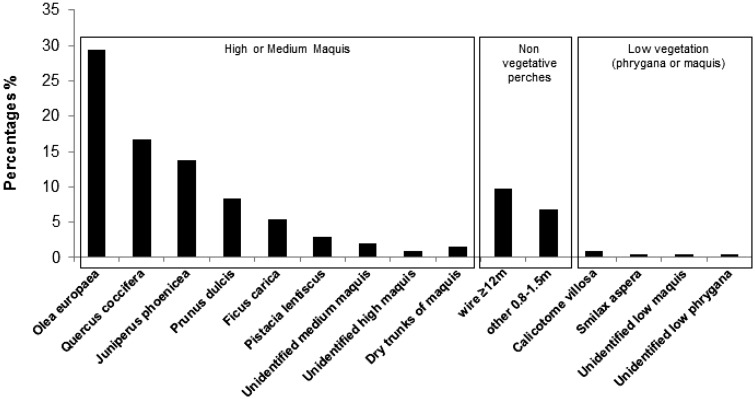

Observations on plant taxon use by the tagged and random woodchat shrikes when conducting hunting attempts toward the ground indicated that the study species tended to swoop from a standing point higher than 0.8 m (Figure 5), for example, from Medium or High Maquis. In particular, during their hunting attempts toward the ground, woodchat shrikes utilized the following plant taxa in descending order: Olea europaea (29.41%), Quercus coccifera (16.67%), Juniperus phoenicea (13.73%), and Prunus dulcis (8.33%). All of these plants were defined as Medium or High Maquis. On the other hand, woodchat shrikes were observed less frequently swooping toward the ground from low vegetation such as Callicotome villosa (0.98%), Smilax aspera (0.49%), or unidentified Low Maquis and Phrygana species (0.98%).

Figure 5.

Plant taxa and non-vegetative perches used for hunting attempts toward the ground by woodchat shrikes, during the spring stopover season 2015, as recorded during behavioral observations of both non-tagged and radio- or color-tagged individuals; y-axis represents the percentages of each perch category (x-axis) among all observations which regard to hunting attempts toward the ground.

Finally, in a total of 12 cases that a raptor was observed in a close proximity (20–40 m) to a woodchat shrike, the latter was hiding inside the maquis were it was perched, until the raptor moved further away. This behavior was interpreted as an anti-predator strategy.

Discussion

In accordance with our initial hypothesis, in our study we have shown that habitat use by woodchat shrikes stopping over at the island of Antikythira (Greece) in spring is associated with both high maquis vegetation and low vegetation. Such tall perches surrounded by low vegetation provide good visibility of both ground dwelling prey and predators. Indeed, among the observed hunting attempts woodchat shrikes were mostly swooping from a high perch heading toward the ground. In the presence of a raptor, high maquis vegetation might also provide shelter to woodchat shrikes. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to describe microhabitat use of a Shrike species, just after the crossing of the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert using both color tags and radio telemetry. Woodchat shrikes differ from other passerines as they are considered sit-and-wait predators, which scan the surrounding ground and air for prey from a concealed point and surprise their prey with a rapid attack (Yosef et al. 2012).

In a wider context, migratory bird populations can be influenced by events that occur during the over-wintering, migration, and breeding periods (Norris and Taylor 2006; Rushing et al. 2016). This implies that the observed behavior of the migrants at stopover sites is affected by their body condition upon arrival, which is influenced by events that took place elsewhere. A stopover period could determine, in turn, crucial parts of the life cycle, including breeding performance. This indicates the significance of stopovers for the fitness of the individuals and the viability of their populations. Thus, it highlights the importance of the study and management of stopover sites.

The microhabitat use described here might be characteristic for those migrating woodchat shrikes that choose to stopover on xeric ecosystems that dominate most of the Mediterranean islands (Katsimanis et al. 2006). On the island of Antikythira, woodchat shrikes’ microhabitat use was linked to hunting attempts directed toward the ground, which likely represents an efficient foraging strategy. In particular, woodchat shrikes used branches of the highest vegetation, available on the island, as hunting perches and then they dived toward the ground to catch their prey. Similarly, Sandor et al. (2004) showed that woodchat shrikes, during a spring time stopover in Romania, mainly exhibited hunting attempts toward the ground by utilizing perches of 1.2–2.2 m height, very similar to the height of Medium and High Maquis on the island of Antikythira. On the contrary, at a breeding site in Switzerland, hovering flights of woodchat shrikes were more productive and outnumbered the ones directed toward the ground (Schaub 1996).

These dissimilarities may be a result of differences in the abundance of the main prey of the woodchat shrikes. In particular beetles (Coleoptera) in spring may be more abundant than grasshoppers (Orthoptera) as shown by Hernández et al. (1993) and Sandor et al. (2004). Similar seasonal differences in prey abundance on their stopover on the island of Antikythira may lead woodchat shrikes to perform hunting attempts toward the ground to catch the most abundant food source during this time of the year. Indeed, migrants have been shown to shift foraging tactics during migration as a response to seasonal prey availability and body condition (Smith et al. 2004; Powell et al. 2015). Loggerhead shrikes Lanius ludovicianus, which are also considered sit-and-wait predator, alter their hunting behavior according to the height of the available vegetation before or after mowing (Yosef and Grubb 1993). Data on the abundance of flying insects during spring on the island of Antikythira in comparison to the abundance of ground-dwelling invertebrates could further elucidate the role of prey availability on the observed hunting strategies during stopover.

Another study in the breeding grounds of the woodchat shrike in the Mediterranean France highlighted the effect of 2 fundamental habitat components: (1) a low and discontinuous grass layer where the birds collect their prey (mostly beetles) and (2) the presence of isolated trees, shrubs, or bushes used as surveying and hunting posts as well as nesting sites (Isenmann and Fradet 1998). Our GLMMs’ results suggest a similar pattern during the spring stopover period, because woodchat shrikes are more likely to be observed in microhabitats of High Maquis surrounded by low vegetation. Further data on habitat use during the wintering period could clarify whether these 2 habitat components are crucial throughout the annual cycle of the woodchat shrikes.

Our results showed that the woodchat shrikes probably use the medium and high maquis vegetation not only to make hunting attempts but they also use their canopy as shelter against raptors. It has been reported that migrants expose themselves to higher predation risk at stopover sites as they increase their foraging intensity, in order to refuel and continue their migration (Alerstam 2011). It seems that woodchat shrikes utilize High Maquis as hunting perches, while at the same time they can hide there when a raptor is in a close proximity.

This study illustrated the importance of a Mediterranean Island’s higher maquis taxa during stopover of woodchat shrikes. In the near future we aim to examine whether parameters such as body condition (weight, fat, and muscles), experience (age), interactions among conspecifics (e.g., competition), and food availability can influence the stopover duration or the time the birds spend to find the optimal habitat for refueling. Given that we rarely observed aggressive behavior among woodchat shrikes during our study (Papageorgiou et al., in preparation), even in periods with high abundance of woodchat shrikes on the island, we hypothesize that stopover duration and home range size are most likely affected by factors such as age or body condition. For example, less experienced birds might spend more time in search of suitable perches, and hence, they utilize wider areas. Nonetheless, as discussed by Seewagen et al. (2010) the actual time spent for stopover is hard to estimate given that it depends on the probability of capturing a bird immediately following landfall. Although habitat availability could not be estimated from the data in hand, the high occurrence of the woodchat shrikes in high maquis vegetation, despite the relatively lower percentage cover of this habitat type in relation to phrygana across the island, could serve as a first indication of the habitat preferences of the species. The use of a 4 m2 plot to estimate microhabitat use allowed us to delineate only the most preferred perches and their immediate surroundings. Thus, a detailed vegetation map would allow us to study habitat use in relation to habitat availability and consequently will enable us to investigate habitat selection by woodchat shrikes during their stopover at various spatial scales (form the microhabitat to the study area level) on Antikythira Island. However, such a detailed mapping of our study area is currently lacking. In addition, knowledge of the study species’ diet and the abundance of their preferred prey in the examined habitat types could further elucidate which factors drive habitat selection by woodchat shrikes at this spring time stopover site.

In conclusion, in this first study of microhabitat use by woodchat shrikes during stopover on a Mediterranean island, after the crossing of the Sahara Desert, we showed that a better hunting position and safety provision are of top priority for that species, because they choose high vegetation as perches for hunting and shelter. Apart from the autochthonous taxa such as Q.coccifera orJ.phoenicea, woodchat shrikes tended to occur on almond P.dulcis and olive trees O.europaea, which have been traditionally cultivated on the island, yet to a small extent. We thereby encourage conservation and preservation of these cultivated species while maintaining anthropogenic disturbance at a low level in native maquis habitats. Such practices are expected to benefit woodchat shrikes’ stopover on the island, as well as to enhance the ecological value of local ecosystems.

Acknowledgments

This is contribution No. 18 from Antikythira Bird Observatory—Hellenic Ornithological Society. We thank all the volunteers of Antikythira Bird Observatory in spring 2015 for assisting in mist netting and ringing and the field owners who provided free access to their ground. Animal handling complied with the current laws of Greece.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Leventis Foundation, Life Program: “LIFE13 NAT/GR/000909 Conservation measures to assist the adaptation of Falco eleonorae to climate change” and the “Andreas Mentzelopoulos” scholarships for master studies in the University of Patras. Rings were supplied free of charge by the Hellenic Bird Ringing Centre.

Appendix

Figure A.

The 100% MCP of each tracked (radio-tagged or color-ringed) individual on Antikythira Island during the spring 2015 stopover period.

Table A.

The GLMMs considered in the model selection procedure which was based on the Akaike information criterion corrected for the sample size (AICc: corrected Akaike information criterion, K = number of parameters, abbreviations of habitat categories as in Table 1)

| Model | Variables | AIC | K | AICc | ΔAICc | Akaike weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m57 | HMa + BG + LGr2 + LPh2 + HMa2 ++ LMa2 + Hma:LMa2 | 549.4 | 9 | 549.7 | 0 | 0.77 |

| m43 | HMa + BG + LGr2 + LPh2 + HMa2 + LMa2 | 552.4 | 8 | 552.7 | 2.933 | 0.18 |

| m39 | HMa + BG + LGr2 + LPh2 + HMa2 | 555.6 | 7 | 555.8 | 6.073 | 0.04 |

| m40 | HMa + BG + LGr2 + LPh2 + LMa2 | 557.4 | 7 | 557.6 | 7.873 | 0.01 |

| m37 | HMa + BG + LGr2 + LPh2 | 560 | 6 | 560.2 | 10.42 | 0.00 |

| m33 | HMa + BG + LGr2 + LPh | 563.8 | 6 | 564 | 14.22 | 0.00 |

| m36 | HMa + BG + LGr2 + LMa2 | 574.2 | 6 | 574.4 | 24.62 | 0.00 |

| m35 | HMa + BG + LGr2 + HMa2 | 574.4 | 6 | 574.6 | 24.82 | 0.00 |

| m29 | HMa + BG + LGr2 | 579.9 | 5 | 580 | 30.28 | 0.00 |

| m25 | HMa + BG + LGr | 585.4 | 5 | 585.5 | 35.78 | 0.00 |

| m30 | HMa + BG + LMa2 | 595.2 | 5 | 595.3 | 45.58 | 0.00 |

| m31 | HMa + BG + LPh2 | 598.7 | 5 | 598.8 | 49.08 | 0.00 |

| m28 | HMa + BG + HMa2 | 602.2 | 5 | 602.3 | 52.58 | 0.00 |

| m26 | HMa + BG + LPh | 603.7 | 5 | 603.8 | 54.08 | 0.00 |

| m17 | HMa + BG | 608 | 4 | 608.1 | 58.34 | 0.00 |

| m20 | HMa + BG2 | 619.3 | 4 | 619.4 | 69.64 | 0.00 |

| m22 | HMa + LGr2 | 625.1 | 4 | 625.2 | 75.44 | 0.00 |

| m18 | HMa + LGr | 629.7 | 4 | 629.7 | 80.01 | 0.00 |

| m23 | HMa + LMa2 | 630.9 | 4 | 631 | 81.24 | 0.00 |

| m24 | HMa + LPh2 | 640.7 | 4 | 640.8 | 91.04 | 0.00 |

| m19 | HMa + LPh | 646.3 | 4 | 646.4 | 96.64 | 0.00 |

| m21 | HMa + HMa2 | 646.3 | 4 | 646.4 | 96.64 | 0.00 |

| m3 | HMa | 649.9 | 3 | 649.9 | 100.2 | 0.00 |

| m1 | BG | 660.9 | 3 | 660.9 | 111.2 | 0.00 |

| m11 | HMa2 | 666.1 | 3 | 666.1 | 116.4 | 0.00 |

| m9 | BG2 | 690.7 | 3 | 690.7 | 141 | 0.00 |

| m13 | LGr2 | 704.1 | 3 | 704.1 | 154.4 | 0.00 |

| m5 | LGr | 721.4 | 3 | 721.4 | 171.7 | 0.00 |

| m15 | LPh2 | 735.2 | 3 | 735.2 | 185.5 | 0.00 |

| m7 | LPh | 741.5 | 3 | 741.5 | 191.8 | 0.00 |

| m14 | LMa2 | 761.4 | 3 | 761.4 | 211.7 | 0.00 |

References

- Akaike H, 1974. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Automat Contr 19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Alerstam T, Lindström Å, 1990. Optimal bird migration: the relative importance of time, energy, and safety In: Gwinner E, editor. Bird Migration: the Physiology and Ecophysiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 331–351. [Google Scholar]

- Alerstam T, 2011. Optimal bird migration revisited. J Ornithol 152:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann J, 1974. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour 49:227–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlettaz R, Maurer ML, Mosimann-Kampe P, Nussle S, Abadi F. et al. , 2012. New vineyard cultivation practices create patchy ground vegetation, favouring woodlarks. J Ornithol 153:229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bairlein F, 1985. Body weights and fat deposition of Palaearctic passerine migrants in the central Sahara. Oecologia 66:141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairlein F, 1983. Habitat selection and associations of species in European passerine birds during southward, post-breeding migrations. Ornis Scand 14:239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker. 2015. lme4: Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- BirdLife International and Nature Serve, 2015. Bird Species Distribution Maps of the World. Cambridge (UK): BirdLife International, and Arlington, USA: Nature Serve.

- Blondel J, Aronson J, 1999. Biology and Wildlife of the Mediterranean Region. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlin MS, Cochran WW, Wikelski MC, 2005. Biotelemetry of New World thrushes during migration: physiology, energetics and orientation in the wild. Integr Comp Biol 45:295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR, 2002. Model selection and Multimodel inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. 2nd edn. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Chernetsov N, Mukhin A, 2006. Spatial behavior of European Robins during migratory stopovers: a telemetry study. The Wilson J Ornithol 118:364–373. [Google Scholar]

- Chernetsov N, 1998. Habitat distribution during the postbreeding and post-hedging period in the reed warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus and sedge warbler A. schoenobaenus depends on food abundance. Ornis Svec 8:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chernetsov N, 2012. Passerine Migration: Stopovers and Flight. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- CyberTracker Conservation, 2013. CyberTracker Version 3.393. Available from: http://www.cybertracker.org.

- Delingat J, Dierschke V, Schmaljohann H, Mendel B, Bairlein F, 2006. Daily stopovers as optimal migration strategy in a long-distance migrating passerine: the northern wheatear Oenanthe oenanthe. Ardea 94:593. [Google Scholar]

- Drent R, Both C, Green M, Madsen J, Piersma T. et al. , 2003. Pay-offs and penalties of competing migratory schedules. Oikos 103:274–292. [Google Scholar]

- Engler R, Guisan A, Rechsteiner L, 2004. An improved approach for predicting the distribution of rare and endangered pecies from occurrence and pseudo-absence data. J Appl Ecol 41:263–274. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI, 2012. ArcGIS Desktop for Windows. Version 10.1. Redlands, CA: ESRI. [Google Scholar]

- Flaquer C, Puig-Montserrat X, Burgas A, Russo D, 2008. Habitat selection by Geoffroy’s bats Myotis emarginatus in a rural Mediterranean landscape: implications for conservation. Acta Chiropterol 10:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gargallo G, Barriocanal C, Castany J, Clarabuch O, Escandell R. et al. , 2011. Spring migration in the western Mediterranean and NW Africa: the results of 16 years of the Piccole Isole project. Monografies Del Museu De Ciències Nat 6:1–364. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison XA, Blount JD, Inger R, Norris DR, Bearhop S, 2011. Carry-over effects as drivers of fitness differences in animals. J Anim Ecol 80:4–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedenström A, Alerstam T, 1997. Optimum fuel loads in migratory birds: distinguishing between time and energy minimization. J Theor Biol 189:227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández A, Purroy F, Salgado J, 1993. Seasonal variation, interspecific overlap, and diet selection in three sympatric shrike species (Lanius spp.). Ardeola 40:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto RL, 1985a. Seasonal changes in the habitat distribution of transient insectivorous birds in southeastern Arizona: competition mediated? The Auk 102:120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto RL, 1985b. Habitat selection by nonbreeding, migratory land birds In: Cody ML, editor. Habitat Selection in Birds. Orlando, Florida: Academic Press, 455–476. [Google Scholar]

- Isenmann P, Fradet G, 1998. Nest site, laying period, and breeding success of the woodchat shrike Lanius senator in Mediterranean France. J Für Ornithologie 139:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Katsimanis N, Dretakis M, Akriotis T, Mylonas M, 2006. Breeding bird assemblages of eastern Mediterranean shrublands: composition, organisation and patterns of diversity. J Ornithol 147:419–427. [Google Scholar]

- Lank DB, Ydenberg RC, 2003. Death and danger at migratory stopovers: problems with “predation risk”. J Avian Biol 34:225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom A, Alerstam T, 1992. Optimal fat loads in migrating birds: a test of the time-minimization hypothesis. Amer Nat 140:477–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locus, 2014. Locus Map Free. Version 3.13.0. Available from: http://www.locusmap.eu/.

- Martin TE, Karr JR, 1986. Patch utilization by migrating birds: resource oriented? Ornis Scand 17:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe JD, Olsen BJ, 2015. Tradeoffs between predation risk and fruit resources shape habitat use of landbirds during autumn migration. The Auk 132:903–913. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhin A, Chernetsov N, Kishkinev D, 2008. Acoustic information as a distant cue for habitat recognition by nocturnally migrating passerines during landfall. Behav Ecol 19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Naef-Daenzer B, 2007. An allometric function to fit leg-loop harnesses to terrestrial birds. J Avian Biol 38:404–407. [Google Scholar]

- Newton I, 2008. The Migration Ecology of Birds. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norris DR, Taylor CM, 2006. Predicting the consequences of carry-over effects for migratory populations. Biol Lett 2:148–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C, Colledge S, Bevan A, Conolly J, 2010. Vegetation recolonisation of abandoned agricultural terraces on Antikythera, Greece. Env Archaeol 15:64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Patthey P, Signorell N, Rotelli L, Arlettaz R, 2012. Vegetation structural and compositional heterogeneity as a key feature in Alpine black grouse microhabitat selection: conservation management implications. Eur J Wildl Res 58:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister C, Kasprzyk MJ, Harrington BA, 1998. Body-fat levels and annual return in migrating semipalmated sandpipers. The Auk 115:904–915. [Google Scholar]

- Pilastro A, Macchio S, Massi A, Montemaggiori A, Spina F, 1998. Spring migratory routes of eight trans‐Saharan passerines through the central and western Mediterranean; results from a network of insular and coastal ringing sites. Ibis 140:591–598. [Google Scholar]

- Powell LL, Dobbs RC, Marra PP, 2015. Habitat and body condition influence American Redstart foraging behavior during the non-breeding season. J Fie Ornithol 86:229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Rappole JH, Tipton AR, 1991. New harness design for attachment of radio transmitters to small passerines (Nuevo Diseno de Arnés para Atar Transmisores a Passeriformes Pequenos). J Fie Ornithol 62:335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Rushing CS, Ryder TB, Marra P, 2016. Quantifying drivers of population dynamics for a migratory bird throughout the annual cycle. Proc Roy Soc B 283:2040–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo D, Jones G, Migliozzi A, 2002. Habitat selection by the Mediterranean horseshoe bat Rhinolophus Euryale (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae) in a rural area of southern Italy and implications for conservation. Biol Conserv 107:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg R, Moore FR, 1996. Fat stores and arrival on the breeding grounds: reproductive consequences for passerine migrants. Oikos 77:577–581. [Google Scholar]

- Sandor AD, Maths I, Sima I, 2004. Hunting behaviour and diet of migratory woodchat shrikes Lanius senator in Eastern Romania. Biol Lett 41:167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sapir N, Tsurim I, Gal B, Abramsky Z, 2004. The effect of water availability on fuel deposition of two staging Sylvia warblers. J Avian Biol 35:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub M, Jenni L, Bairlein F, 2008. Fuel stores, fuel accumulation, and the decision to depart from a migration stopover site. Behav Ecol 19:657–666. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub M, 1996. Jagdverhalten und Zeitbudget von Rotkopfwürgern Lanius senator in der Nordwestschweiz. Journal Für Ornithologie 137:213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Seewagen CL, Slayton EJ, Guglielmo CG, 2010. Passerine migrant stopover duration and spatial behaviour at an urban stopover site. Acta Oecol 36:484–492. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, Hamas MJ, Ewert DN, Dallman ME, 2004. Spatial foraging differences in American redstarts along the shoreline of northern Lake Huron during spring migration. Wilson Bull 116:48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, Moore FR, 2003. Arrival fat and reproductive performance in a long-distance passerine migrant. Oecologia 134:325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina F, Piacentini D, Montemaggiori A, 2006. Bird migration across the Mediterranean: ringing activities on Capri within the Progetto Piccole Isole. Ornis Svecica 16:20–26. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc., 2014. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Chicagο: SPSS Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson L, 1992. Identification Guide to European Passerines. Norfolk: British Trust for Ornithology. [Google Scholar]

- Team RC., 2015. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Titov N, 2000. Interaction between foraging strategy and autumn migratory strategy in the robin Erithacus rubecula. Avian Ecol Behav 5:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tøttrup AP, Thorup K, Rainio K, Yosef R, Lehikoinen E, 2008. Avian migrants adjust migration in response to environmental conditions en route. Biol Lett 4:685–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White G, Garrott R, 1990. Analysis of Wildlife Radio-Tracking Data. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wikelski M, Tarlow EM, Raim A, Diehl RH, Larkin RP, 2003. Avian metabolism: costs of migration in free-flying songbirds. Nature 423:704–704.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef R, Grubb TC Jr., 1993. Effect of vegetation height on hunting behavior and diet of loggerhead shrikes. Condor 95:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Yosef R, Grubb TC, 1994. Resource dependence and territory size in loggerhead shrikes Lanius ludovicianus. The Auk 111:465–469. [Google Scholar]

- Yosef R, Markovets M, Mitchell L, Tryjanowski P, 2006. Body condition as a determinant for stopover in bee-eaters Merops apiaster on spring migration in the Arava Valley, southern Israel. J Arid Env 64:401–411. [Google Scholar]

- Yosef R, 2008. Family Laniidae (shrikes).In: del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Christie D, editors. Handbook of the Birds of the World: Penduline-tits to Shrikes. Vol. 13 Barcelona: Lynx Editions, 732–773. [Google Scholar]

- Yosef R, Zduniak P, Tryjanowski P, 2012. Unmasking Zorro: functional importance of the facial mask in the masked shrike Lanius nubicus. Behav Ecol 23:615–618. [Google Scholar]

- Yosef R, 1993. Influence of observation posts on territory size of northern shrikes. Wilson Bull 105:180–183. [Google Scholar]

- Zduniak P, Yosef R, 2012. Crossing the desert barrier: Migration ecology of the lesser whitethroat Sylvia curruca at Eilat, Israel. J Arid Env 77:32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zduniak P, Yosef R, 2011. Migration and staging patterns of the red-throated Anthus cervinus and tree pipits Anthus trivialis at the migratory bottleneck of Eilat, Israel. Ornis Fennica 88:129. [Google Scholar]