Abstract

BACKGROUND

Angiostrongyliasis is an infection caused by nematode worms of the genus Angiostrongylus. The adult worms inhabit the pulmonary arteries, heart, bronchioles of the lung, or mesenteric arteries of the caecum of definitive host. Of a total of 23 species of Angiostrongylus cited worldwide, only nine were registered in the American Continent. Two species, A. cantonensis and A. costaricensis, are considered zoonoses when the larvae accidentally parasitise man.

OBJECTIVES

In the present study, geographical and chronological distribution of definitive hosts of Angiostrongylus in the Americas is analysed in order to observe their relationship with disease reports. Moreover, the role of different definitive hosts as sentinels and dispersers of infective stages is discussed.

METHODS

The study area includes the Americas. First records of Angiostrongylus spp. in definitive or accidental hosts were compiled from the literature. Data were included in tables and figures and were matched to geographic information systems (GIS).

FINDINGS

Most geographical records of Angiostrongylus spp. both for definitive and accidental hosts belong to tropical areas, mainly equatorial zone. In relation to those species of human health importance, as A. cantonensis and A. costaricensis, most disease cases indicate a coincidence between the finding of definitive host and disease record. However, in some geographic site there are gaps between report of definitive host and disease record. In many areas, human populations have invaded natural environments and their socioeconomic conditions do not allow adequate medical care.

MAIN CONCLUSIONS

Consequently, many cases for angiostrongyliasis could have gone unreported or unrecognised throughout history and in the nowadays. Moreover, the population expansion and the climatic changes invite to make broader and more complete range of observation on the species that involve possible epidemiological risks. This paper integrates and shows the current distribution of Angiostrongylus species in America, being this information very relevant for establishing prevention, monitoring and contingency strategies in the region.

Key words: American distribution, angiostrongyliasis, Angiostrongylus, disease reports

Angiostrongyliasis is an infection caused by nematode worms of the genus Angiostrongylus Kamensky 1905. The adult worms inhabit the pulmonary arteries, vena cava and right ventricle of the heart, bronchioles of the lung, or mesenteric arteries of the caecum of definitive host, which include rodents, tupaiids, mephitids, mustelids, procyonids, felids, or canids, and aberrantly in a range of avian, marsupial and eutherian hosts including humans (Anderson et al. 2010). Definitive hosts release first-stage larvae in the feces, which utilise slugs and/or aquatic or terrestrial snails as intermediate hosts. Gastropods are infected by ingestion or penetration of first-stage larvae; while definitive hosts are infected by ingestion of gastropods or their slime. Also, the transmission could involve ingestion of paratenic hosts (Cross 2004, Thiengo 2007, Spratt 2015).

Of a total of 23 species of Angiostrongylus cited worldwide, only nine were registered in the American Continent: Angiostrongylus vasorum (Bailliet, 1866), Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen 1935), Angiostrongylus raillieti Travassos 1927, Angiostrongylus gubernaculatus Dougherty 1946, Angiostrongylus costaricensis Morera and Céspedes 1971, Angiostrongylus schmidti Kinsella 1971, Angiostrongylus morerai Robles, Navone and Kinsella 2008, Angiostrongylus lenzii Souza, Simões, Thiengo et al. 2009 and Angiostrongylus felineus Vieira et al. 2013 (Kinsella 1971, Robles et al. 2008, Souza et al. 2009, Vieira et al. 2013, Spratt 2015).

Two species, A. cantonensis and A. costaricensis, causing neurological and abdominal angiostrongyliasis respectively, are considered zoonoses when the larvae accidentally parasitise man. There are many reports of these diseases in different American countries (Acha & Szyfres 2003, Maldonado Jr et al. 2010, Spratt 2015). Angiostrongylus vasorum, causing a respiratory pathology in wild and domestic canids, has veterinary importance (Koch & Willesen 2009). The rest of Angiostrongylus species only are known in wild animals and there are no data on their epidemiological potential (Spratt 2015, Robles et al. 2016).

Some studies (Kinsella 1971, Robles et al. 2016) suggest the low host specificity of Angiostrongylus spp. Besides that, other studies as Spratt (2015) warns that most of the reports of these species only reflect lack of opportunity or interest in examining nonurban and nonagricultural hosts.

It is puzzling that there has been no cases of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis or abdominal angiostrongyliasis in some points of the American distribution to date, even considering that the characteristics of the environment and the presence of several intermediate hosts (registered and potential) and wild definitive host allow the presence of different species of Angiostrongylus (Robles et al. 2008, 2016, Souza et al. 2009, Maldonado Jr et al. 2010).

As in most natural systems, the climate change affects physiology of hosts and parasite, altering survivorship, reproduction, and transmission, among other factors. In addition, in different parts of the world, the environment and socioeconomic systems are changing rapidly, modifying interactions among humans, animals, and their pathogens (Kutz et al. 2005, Salb et al. 2008).

In the present study, geographical and chronological distribution of definitive hosts of Angiostrongylus in the Americas is analysed in order to observe their relationship with disease reports. Moreover, the role of different definitive hosts as sentinels and dispersers of infective stages is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study area includes the Americas (i.e. North, Central and South America, and Caribbean). First records of the parasite of Angiostrongylus spp. in definitive or accidental hosts were compiled from the literature (scientific literatures and book sections). When necessary, scientific names of mammal hosts have been updated following Wilson and Reeder (2005) and Weksler et al. (2006). Published disease reports in non-indexed journals or in internal articles of regional hospitals were reviewed and most of them included, however some cases were ignored for not showing clear evidence.

Data were included in Tables I–III and were matched to geographic information systems (GIS) using QUANTUM GIS (Version 2.10 PISA). Coordinates of geographical sites were obtained from the gazetteer GeoHack Web Application. The first records of adult parasite, disease, or both at once are showed in the maps with different symbols (Figs 1–2). Geographic sites that are located in the same state were plotted in a single point on the figures.

TABLE I. Reports of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the Americas and in Hawaii, showing date of first report of adult parasite in chronological order, definitive hosts, and date of the first disease record in each geographical site. Numbers and symbol correspond to the references in Fig. 1 .

| Nematode species | Reference in map | First record of adult parasite | Definitive host | First record disease | Accidental host | Geographical site | Literature consulted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiostrongylus cantonensis | 1960 | Rattus rattus | 1960 | Homo sapiens | Hawaii* | Alicata (1991) | |

| Rattus norvegicus | |||||||

| 1 | 1977 | R. norvergicus | 1981 | H. sapiens | Cuba* | Aguiar et al. (1981) | |

| 2 | 1980 | Sigmodon hispidus | 1980 | H. sapiens | Costa Rica* | Núñez and Mirambell (1981) | |

| R. rattus | |||||||

| 3 | 1984 | R. rattus R. norvegicus | 1986 | H. sapiens | Puerto Rico* | Anderson et al. (1986) | |

| 4 | 1987 | R. rattus | 1990 | Hylobates lyr | Bahamas, USA | Vargas et al. (1992) | |

| R. norvegicus | |||||||

| 5 | 1988 | R. norvergicus | 1992 | Alouatta caraya | Louisiana, USA | Campbell and Little (1988), Cross (2004) | |

| Podomys floridanusa | Lemur variegatus | ||||||

| Didelphis virginiana | Cercophitecus | ||||||

| R. norvergicus | talapon | ||||||

| Varecia variegata | H. sapiens | ||||||

| 6 | 1992 | R. rattus | 1992 | H. sapiens | Republica | Vargas et al. (1992) | |

| Dominicana* | |||||||

| 7 | 1994 | R. rattus | 1994 | H. sapiens | Jamaica* | Lindo et al. (2002) | |

| R. norvegicus | |||||||

| 8 | 2002 | R. rattus | - | - | Puerto Principe, Haiti | Raccurt et al. (2003) | |

| R. norvergicus | |||||||

| 9 | 2003 | R. rattus | 2003 | H.lyr | Florida, USA | Cross (2004), Duffy et al. (2004) | |

| R. norvergicus | |||||||

| 10 | 2007 | R. norvegicus | 2007 | H. sapiens | Espírito Santo, Brazil | Caldeira et al. (2007) | |

| 11 | 2008 | R. norvergicus | 2008 | H. sapiens | Guayas, Ecuador | Martini-Robles and Dorta Contreras (2016) | |

| 12 | - | - | 2009 | H. sapiens | Pernambuco, Brazil | Lima et al. (2009) | |

| 13 | 2010 | R. norvergicus | 2007 | H. sapiens | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Simões et al. (2011) | |

| Morassutti et al. (2014) | |||||||

| 14 | - | 2010 | H. sapiens | São Paulo, Brazil | Espírito Santo et al. (2013) | ||

| 15 | 2013 | R. rattus | - | - | Pará, Brazil | Morassutti et al. (2014) | |

| R. norvergicus | |||||||

| 16 | 2013 | R. norvergicus | 2013 | H. sapiens | Rio Grande do Sul, | Cognato et al. (2013) | |

| Brazil | Morassutti et al. (2014) | ||||||

| 17 | 2013 | R. rattus | 2013 | H. sapiens | Guadalupe | Dard et al. (2017) | |

| R. norvegicus |

the country capital coordinates were used since the localities were not provided. Registered as a: Neotoma floridanus.

TABLE III. Reports of Angiostrongylus spp. (except A. cantonensis and A. costaricensis) in the Americas, showing date of first report of adult parasite in chronological order, definitive hosts, and date of the first disease record in each geographical site. Numbers correspond to references in Fig. 3 .

| Nematode species | Reference in map | First record of adult parasite | Definitive host | First record disease | Accidental host | Geographical site | Literature consulted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiostrongylus vasorum | 1 | 1961 | Canis familiaris | Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil | Duarte et al. (2007) | ||

| 2 | 1962 | C. familiaris | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Duarte et al. (2007) | |||

| Cerdocyon thous | |||||||

| 3 | 1985 | C. familiaris | Paraná, Brazil | Duarte et al. (2007) | |||

| 4 | 1985 | C. familiaris | Minas Gerais, Brazil | Duarte et al. (2007) | |||

| Dusicyon vetulus | |||||||

| 5 | 2000 | Vulpes vulpes | Newfoundland, Canadá | Jeffery et al. (2004) | |||

| C. familiaris | |||||||

| Angiostrongylus raillieti | 6 | 1927 | Cerdocyon thous azarae | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Vieira et al. (2013) | ||

| C. familiaris | |||||||

| Nasua nasua | |||||||

| Angiostrongylus gubernaculatus | 7 | 1971 | Taxidea taxus | California, USA | Faulkner et al. (2001) | ||

| Urocyon littoralis | |||||||

| Angiostrongylus schmidti | 8 | 1971 | Oryzomys palustris | Florida, USA | Kinsella (1971) | ||

| Angiostrongylus morerai | 9 | 2008 | Akodon azarae | Buenos Aires, Argentina | Robles et al. (2008) Robles et al. (2016) | ||

| Akodon dolores | |||||||

| Deltamys kempi | |||||||

| 10 | 2016 | Necromys lasiurus liciae | Formosa, Argentina | Robles et al. (2016) | |||

| Calomys callosus | |||||||

| Akodon azarae bibianae | |||||||

| 11 | 2016 | Akodon montensis Sooretamys angouya | Misiones, Argentina | Robles et al. (2016) | |||

| Angiostrongylus lenzii | 12 | 2009 | Akodon montensis | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Souza et al. (2009) | ||

| Angiostrongylus felineus | 13 | 2013 | Puma yagouaroundi | Minas Gerais, Brazil | Vieira et al. (2013) |

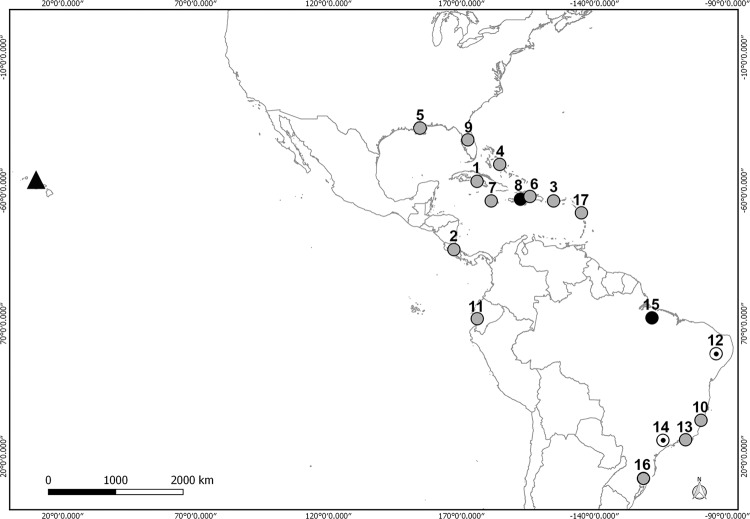

Fig. 1. Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the Americas and Hawaii (▲) showing reports of adult parasites without disease (black points), and reports of adult parasite and disease (grey points) (references in Table I).

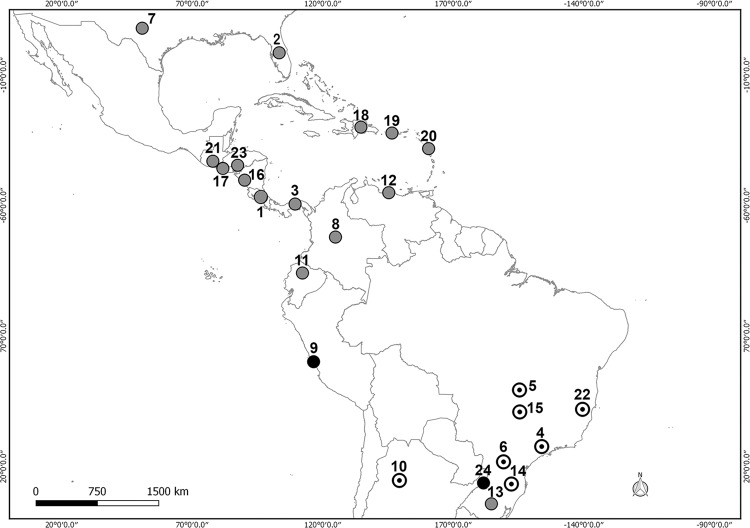

Fig. 2. Angiostrongylus costaricensis in the Americas showing reports of adult parasites without disease (black points), report of disease (white point), and reports of adult parasite and disease (grey points) (references in Table II).

RESULTS

In 36 geographic sites, at least one of the nine species of Angiostrongylus was reported. While disease records by angiostrongyliasis were obtained in 28 geographic sites. The Pan-American distributions of Angiostrongylus were five species in North America, two in Central America, seven in South America, and two in Caribbean (Tables I–III, Figs 1–3).

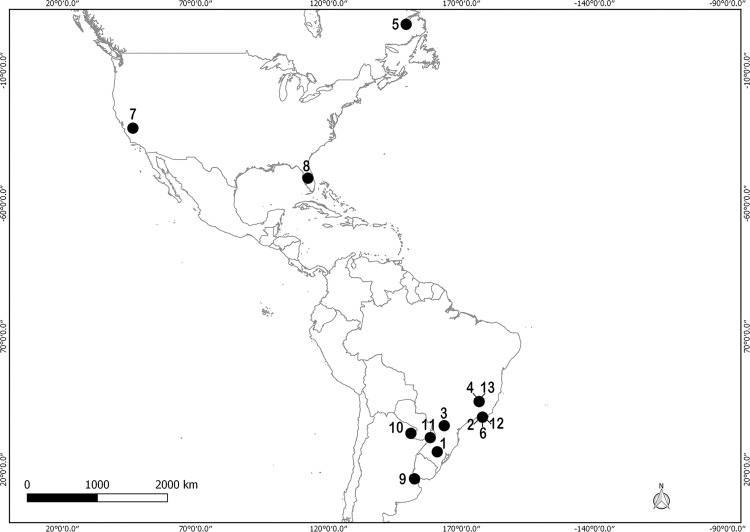

Fig. 3. Angiostrongylus spp. (except A. cantonensis and A. costaricensis) in the Americas (references in Table III).

A. cantonensis was recorded in 16 geographic sites along the continent, six definitive host species and five accidental species affected by disease (Table I, Fig. 1).

On the map the distribution of this species is concentrated mostly in the area between the 29°58′0″N, 90°3′0″W and 27°16′12″S, 50°29′24″W coordinates. Seven points are located in South America, of which six are in Brazil and one in Ecuador (Fig. 1). Of the total records, only four do not indicate a coincidence between the finding of definitive host and disease record, of which three are in Brazil and one in Haiti (Table I).

In the case of A. costaricensis, the parasite was recorded in 24 geographic sites, 19 definitive hosts and only two accidental species affected by angiostrongyliasis (Table II, Fig. 2). In the map the distribution of this species is concentrated mostly in the area between the 31°0′0″N, 100°0′0″W and 29°45′36″S, 40°28′48″W coordinates. Thirteen points are located in South America, of which seven are in Brazil, two in Argentina and one each in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela (Fig. 2). The only record of definitive host in Argentina corresponds to one finding in Misiones province. This report is located 1300 km from the case disease in Tucumán province, and 500 km away from diseases cases in Brazil (Fig. 2).

TABLE II. Reports of Angiostrongylus in the Americas, showing date of first report of adult parasite in chronological order, definitive hosts, and date of the first disease record in each geographical site. Numbers correspond to the references in Fig. 2 .

| Nematode species | Reference in map | First record of adult parasite | Definitive host | First record disease | Accidental host | Geographical site | Literature consulted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiostrongylus costaricensis | 1 | 1971 | Rattus norvergicus | 1971 | Homo sapiens | Costa Rica* | Morera and Cespedes (1971) |

| Sigmodon hispidus | Monge et al. (1978) | ||||||

| Rattus rattus | Alfaro-Alarcon et al. (2015) | ||||||

| Nasua narica | |||||||

| Canis familiaris | |||||||

| 2 | 1971 | S. hispidus | 1971 | Aotus | Florida, USA | Ubelaker and Hall (1979) | |

| Didelphis virginiana | nancymaae | ||||||

| Procyon lotor | |||||||

| Symphalangus | |||||||

| syndactylusb | |||||||

| 3 | 1973 | S. hispidus | 1973 | H. sapiens | Panama* | Kaminsky (1996) | |

| R. rattus | |||||||

| Liomys adspersus | |||||||

| Oligoryzomys | |||||||

| fulvescensc | |||||||

| Zygodontomys | |||||||

| brevicaudad | |||||||

| 4 | - | 1975 | H. sapiens | São Paulo, Brazil | Zilliota Jr et al. (1975) | ||

| 5 | - | 1980 | H. sapiens | Brasilia, Brazil | Agostini et al. (1984) | ||

| 6 | - | 1982 | H. sapiens | Paraná, Brazil | Ayala (1987) | ||

| 7 | 1979 | S. hispidus | 1994 | H. sapiens | Texas, USA | Miller et al. (2006) | |

| 8 | 1981 | S. hispidus | 1981 | H. sapiens | Colombia* | Malek (1981) | |

| Melanomys | |||||||

| caliginosuse | |||||||

| 9 | 1982 | Saguinus mystax | 1982 | - | Peru* | Sly et al. (1982) | |

| 10 | - | 1982 | H. sapiens | Tucumán, Argentina | Demo and Pessat (1986) | ||

| 11 | 1983 | R. rattus | 1983 | H. sapiens | Ecuador* | Kaminsky (1996) | |

| R. norvergicus | |||||||

| 12 | 1985 | Proechimys sp. | 1985 | H. sapiens | Venezuela* | Kaminsky (1996) | |

| 13 | 1990 | 0. nigripes | 1983 | H. sapiens | Rio Grande do Sul, | Agostini et al. (1984) | |

| Sooretamys angouyaf | Brazil | Graeff-Teixeira et al. (1990) | |||||

| 14 | - | 1987 | H. sapiens | Santa Catarina, Brazil | Ayala (1987) | ||

| 15 | - | 1991 | H. sapiens | Minas Gerais, Brazil | Rocha et al. (1991) | ||

| Angiostrongylus costaricensis | 16 | 1991 | S. hispidus | 1991 | H. sapiens | Nicaragua* | Duarte et al. (1991) |

| 17 | 1992 | S. hispidus | 1992 | H. sapiens | El Salvador* | Kaminsky (1996) | |

| 18 | 1992 | R. rattus | 1992 | H. sapiens | Republica Dominicana* | Maldonado Jr et al. (2012) | |

| R. norvergicus | |||||||

| 19 | 1992 | R. rattus | 1992 | H. sapiens | Puerto Rico* | Maldonado Jr et al. (2012) | |

| R. norvegicus | |||||||

| 20 | 1992 | R. rattus | 1992 | H. sapiens | Guadalupe* | Kaminsky (1996) | |

| R. norvergicus | |||||||

| 21 | 1994 | S. hispidus | 1994 | H. sapiens | Guatemala* | Kaminsky (1996) | |

| 22 | - | 1995 | H. sapiens | Espírito Santo, Brazil | Pena et al. (1995) | ||

| 23 | 1996 | S. hispidus Peromyscus spp. | 1972 | H. sapiens | Valle de Yegüare, Honduras | Zuñiga et al. (1983) Kaminsky (1996) | |

| Mus musculus | |||||||

| 24 | 2008 | Akodon montensis | - | - | Misiones, Argentina | Robles et al. (2016) |

the exact locality were not provided. Registered as b: Hylobates syndactylus; c: Oryzomys fulvescens; d. Zygodontomys microtinus; e: Oryzomys caliginosus; f. Oryzomus ratticeps.

In relation with those species of importance for the human health, most disease cases indicate a coincidence with the finding of definitive host. However, the period between the finding of definitive hosts and disease cases was 2-4 years for A. cantonensis and 7-24 for A. costaricensis.

The remaining seven Angiostrongylus species were recorded parasitising members of Marsupialia, Rodentia and Carnivora, including a total of 13 geographic sites (Table III, Fig. 3). A. vasorum has veterinary importance and was registered in four definitive hosts species and five geographic sites. This last species was recorded in a single locality from Canada and four from Brazil. Among those Angiostrongylus species parasitising wild carnivores, A. raillieti and A. felineus were recorded in Brazil, while A. gubernaculatus in USA. Among wild rodent parasitic species, A. schmidti was recorded in USA, while A. lenzii was recorded in Brazil and A. morerai in Argentina (Table III, Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study has considered the first record of the adult nematode and the first record of disease as a way of evaluating the chronological distances between them. Additionally, the results in figures and tables showed both geographical distribution and host range of each Angiostrongylus species.

In 1960, two cases of eosinophilic meningitis caused by A. cantonensis were recorded in Hawaii. Notably, the definitive hosts were recorded almost at the same time as the disease. Although, this site is located in a different biogeographic region from those of the American continent (Neotropic and Neartic), the island belongs politically to USA. The constant flow of boats and people between the island and continent could have benefited the dispersion of the parasite (Cowie 2013).

A case of disease by enteric and lymphatic granulomas caused for Strongylida parasite was observed in Costa Rica in 1952 (Céspedes et al. 1967, Morera 1967). Later, the same authors, observed other similar clinical cases and the etiological agent, and described the species as A. costaricensis, considering the man as an accidental host without mentioning the possible definitive hosts (Morera & Céspedes 1971). Since 1972 different definitive hosts of this parasite were recorded, counting a total 19 hosts species (Kaminsky 1996, Romero-Alegría et al. 2014).

In many areas, mainly tropical, human populations have invaded natural environments and their socioeconomic conditions do not allow adequate medical care. Many cases could have gone unreported or unrecognised throughout history (Spratt 2015). Moreover, the population expansion and the climatic changes, invite to make broader and more complete range of observation on the species that involve possible epidemiological risks.

The Pan-American distribution of Angiostrongylus includes nine species. To date, a total of 33 definitive host species, seven accidental host species, and more than 20 intermediate host species have been recorded for those species of human health importance (A. cantonensis, A. costaricensis) (Grewal et al. 2003). For the remaining Angiostrongylus species, several definitive hosts and very few intermediate hosts have been registered. So, the advance in the study of intermediate hosts will be in relation to the knowledge of the definitive hosts and vice versa.

People usually become infected by eating raw or undercooked food contaminated with the larvae of A. cantonensis and A. costaricensis, or when they manipulate intermediate hosts for fishing (Ping-Wang et al. 2008, Romero-Alegría et al. 2014). In particular, a greater number of cases are expected in countries where intermediate hosts come into frequent contact with humans. It can be observed in the maps that A. cantonensis presents a distribution related with areas in which this feeding habit is present (e.g. Ecuador, Jamaica), being the main intermediate hosts reported Lissachatina fulica, Subulina octona, Bradybaena similaris, Pomacea sp., among others (Grewal et al. 2003, Thiengo 2007). In the case of A. costaricensis, although the geographical distribution is similar to A. cantonensis, the geographic and host records include a broader range. This interesting observation give rise to different hypotheses: (1) greater susceptibility of definitive hosts, increasing the probability of dispersing this species; (2) the site of infection of the adult parasite benefits its finding (gastrointestinal tracts of rodents are more studied than lung and heart MRR pers. obs.), so the distribution of A. cantonensis could be underestimated with respect to A. costaricensis. Future models of distribution, as well as experimental studies, would be helpful to clarify the epidemiological risks of contact with the intermediate hosts. Meanwhile, the present work advances and discusses the role of the definitive hosts as dispersers of Angiostrongylus species, taking account their role as sentinels of angiostrongyliasis.

Robles et al. (2016) and Spratt (2015) suggest that the diversity of Angiostrongylus species, as well the range of hosts, is underestimated. This situation could be due to the lack of interest in studying wild species and/or inadequate instruction for the detection of Angiostrongylus. These observations, added to the low specificity recorded for many species of this genus (Kinsella 1971, Robles et al. 2016), generate questions in relation to human health risks that involve some species that have not reported disease yet (e.g. A. morerai, A. schmidti, A. lenzii). The precarious state of knowledge about these species in America can be observed in the tables and on the map provided in this update.

In this work, the relationship between the definitive host records and the registered cases by angiostrongyliasis was observed. In this sense, in the bulk of cases the reports of diseases show correspondence with the findings of the adult parasite in the definitive host.

In Argentina, A. costaricensis was recorded only in one rodent species (A. montensis) in Misiones province (Robles et al. 2016), while a unique case of disease was reported in Tucumán province (Demo & Pessat 1986). The characteristics of the environments and climatic conditions of both geographic sites are very different, and the chronological distance between these reports is 30 years. This time exceeds the periods observed in the rest of the records for this species (0-24 years). The lack of reports on accidental and definitive hosts in Argentina is paradoxical, especially considering that there is not accurate data on the provenance of the patient in the only human case recorded. However, several human cases registered in Brazil since 1990 are located 500 km from Misiones province. Thus, the potential risk increases considering that the boundaries between human and wild animal's populations in the Atlantic forest are becoming increasingly diffuse. In addition, the main intermediate hosts registered for this two Angiostrongylus species (i.e. L. fulica and Phyllocaulis variegatus) are present in Argentina. However, no Angiostrongylus larvae were found in these mollusks to date (Valente et al. 2017).

This paper integrates and shows the current distribution of Angiostrongylus species in the Americas, being this information very relevant for establish prevention, monitoring and contingency strategies in the region.

Footnotes

Financial support: Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT 2010-0924), Universidad Nacional de La Plata (No. 753), Consejo Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica (PUE CEPAVE 2016).

REFERENCES

- Acha PN, Szyfres B. Zoonosis y enfermedades transmisibles comunes al hombre y a los animales. Vol. III. In: Acha PN, Szyfres B, editors. Angiostrongyliasis. Washington DC: OPS; 2003. pp. 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Agostini AA, Marcolan AM, Lisot JMC, Lisot JUF. Angiostrongilíase abdominal. Estudo anátomo-patológico de quatro casos observados no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1984;79(4):443–445. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761984000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar PH, Morera P, Pascual JE. First record of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Cuba. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30(5):963–965. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro-Alarcón A, Veneziano V, Galiero G, Cerrone A, Gutierrez N, Chinchilla A, et al. First report of a naturally patent infection of Angiostrongylus costaricensis in a dog. Vet Parasitol. 2015;212(3-4):431–434. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alicata JE. The discovery of Angiostrongylus cantonensis as a cause of human eosinophilic meningitis. Parasitol Today. 1991;7(6):151–153. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(91)90285-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E, Gubler DJ, Sorenson K, Beddard J, Ash LR. First report of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Puerto Rico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;35(2):319–322. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RC, Chabaud AG, Wilmott S. Keys to the nematode parasite of vertebrates. In: Anderson RC, editor. Strongylida: Metastrongyloidea. Wallingford: CABI International; 2010. pp. 178–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala MAR. Angiostrongiloidíase abdominal. Seis casos observados no Paraná e em Santa Catarina, Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1987;82(1):29–36. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761987000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira RL, Mendonça CLGF, Goveia CO, Lenzi HL, Graeff-Teixeira C, Lima WS, et al. First record of molluscs naturally infected with Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen, 1935) (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(7):887–889. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007000700018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BG, Little MD. The finding of Angiostrongylus cantonesis in rats in New Orleans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38(3):568–573. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Céspedes R, Salas J, Mekbel S, Troper L, Müllner F, Morera P. Granulomas entéricos y linfáticos con intensa eosinofilia tisular producida por un estrongilídeo (Strongylata) Acta Med Costa Rica. 1967;10:235–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cognato BB, Morassutti AL, da Silva AA, Graeff-Teixeira C. First report of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2013;46(5):664–665. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0073-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie RH. Pathways for transmission of angiostrongyliasis and the risk of disease associated with them. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72(6):70–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross J. Angiostrongylus (Parastrongylus) cantonensis in the western hemisphere. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35(1):107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dard C, Piloquet JE, Qvarnstrom Y, Fox LM, M'kada H, Hebert JC, et al. First evidence of angiostrongyliasis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Guadeloupe, lesser Antilles. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96(3):692–697. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demo OJ, Pessat AO. Angiostrongyliasis abdominal. Primer caso humano encontrado en la Argentina. Prensa Med Arg. 1986;73(17):732–738. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte FH, Vieira FM, Louzada GL, Bessa EC, Souzalima S. Occurrence Angiostrongylus vasorum (Baillet, 1866) (Nematoda, Angiostrongylidae) in Cerdocyon thous Linnaeus, 1766 (Carnivora, Canidae) in Minas Gerais state Brasil. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2007;59(4):1086–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte Z, Moreira P, Vuong P. Abdominal angiostrongyliasis in Nicaragua: a clinico-pathological study on a series of twelve case reports. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1991;66(6):259–262. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1991666259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MS, Miller CL, Kinsella JM, Lahunta A. Parastrongylus cantonensis in a nonhuman primate, Florida. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(12):2207–2210. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espírito Santo MC, Pinto PL, da Mota DJ, Gryschek RC. The first case of Angiostrongylus cantonensis eosinophilic meningitis diagnosed in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2013;55(2):129–132. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652013000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner CT, Patton S, Munson L, Johnson EM, Coonan TJ. Angiocaulus gubernaculatus in the Island Fox (Urocyon littoralis) from the California Channel Islands and comments on the diagnosis of Angiostrongylidae nematodes in canid and mustelid hosts. J Parasitol. 2001;87(5):1174–1176. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[1174:AGITIF]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeff-Teixeira C, Ávila-Pires FD, Machado RCC, Camillo-Coura L, Lenzi HL. Identificação de roedores silvestres como hospedeiros do Angiostrongylus costaricensis no sul do Brasil. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1990;32(3):147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal PS, Grewal SK, Tan L, Adams BJ. Parasitism of molluscs by nematodes: types of associations and evolutionary trends. J Nematol. 2003;35(2):146–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RA, Lankester MW, McGrath MJ, Whitney HG. Angiostrongylus vasorum and Crenosoma vulpis in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Newfoundland, Canada. Can J Zool. 2004;82(1):66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky RG. Situación actual de Angiostrongylus costaricensis y la infección en humanos y animales en las Américas. Rev Med Hondureña. 1996;64(4):139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella JM. Angiostrongylus schmidti sp. n. (Nematoda: Metastrongyloidea) from the rice rat, Oryzomys palustris, in Florida, with a key to the species of Angiostrongylus Kamensky, 1905. J Parasitol. 1971;57(3):494–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch J, Willesen JL. Canine pulmonary angiostrongylosis: An update. Vet J. 2009;179(3):348–359. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutz SJ, Hoberg EP, Polley L, Jenkins EJ. Global warming is changing the dynamics of Arctic host-parasite systems. Proc R Soc Lond (Biol) 2005;272(1581):2571–2576. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima A, Mesquita S, Santos S, Aquino E, Rosa L, Duarte F, et al. Alicata disease: neuroinfestation by Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2009;67(4):1093–1096. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2009000600025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindo J, Waugh C, Hall J, Cunningham-Myrie C, Ashley D, Eberhard M. Enzootic Angiostrongylus cantonensis in rats and snails after outbreak of human eosinophilic meningitis in Jamaica. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(3):324–326. doi: 10.3201/eid0803.010316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado A, Jr, Simões R, Thiengo SC. Angiostrongyliasis in the Americas. In: Lorenzo-Morales J, editor. Zoonosis. Rijeka: In-Tech; 2012. pp. 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado A, Jr, Simões RO, Oliveira APM, Motta EM, Fernandez MA, Pereira ZM, et al. First report of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) in Achatina fulica (Mollusca: Gastropoda) from Southeast and South Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105(7):938–941. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762010000700019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek E. Presence of Angiostrongylus costaricensis Morera and Cépedes, 1971 in Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30(1):81–83. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini-Robles L, Dorta Contreras AJ. Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Emergencia en América. Ecuador: Academia; 2016. pp. 1–289. [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Kinsella JM, Garner MM, Evans S, Gullett PA, Schmidt RE. Endemic infections of Parastrongylus (= Angiostrongylus) costaricensis in two species of nonhuman primates, accoons, and an opossum from Miami, Florida. J Parasitol. 2006;92(2):406–408. doi: 10.1645/GE-653R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge E, Arroyo R, Solano E. A new definitive natural host of Angiostrongylus costaricensis (Morera and Céspedes 1971) J Parasitol. 1978;64(1):34–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morassutti AL, Thiengo SC, Fernandez M, Sawanyawisuth K, Graeff-Teixeira C. Eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis: an emergent disease in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109(4):399–407. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276140023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morera P, Céspedes R. Angiostrongylus costaricensis n. sp. (Nematoda: Metastrongyloidea), a new lungworm occurring in man in Costa Rica. Rev Biol Trop. 1971;18(1-2):173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morera P. Granulomas entéricos v linfáticos con intensa eosinofilia tisular producidos por un estrongilideo (Strongylata: Railiet y Henry, 1913) Aspecto parasitológico (Nota Previa). Acta Med Costa Rica. 1967;10:257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez R, Mirambell F. Angiostrongilosis abdominal: un caso de conducta conservadora. Rev Med Hosp Nac Niños de Costa Rica. 1981;16:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Pena GPM, Andrade JS, Filho, Assis SC. Angiostrongylus costaricensis: First record of its occurrence in the state of Espiritu Santo, Brazil, and a review of its geographic distribution. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1995;37(4):369–374. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651995000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping-Wang Q, Lai DH, Zhu XQ, Chen XG, Lun ZR. Human Angiostrongyliasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(10):621–630. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raccurt C, Blaise J, Durette-Desset M. Présence d'Angiostrongylus cantonensis en Haiti. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8(5):423–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles MR, Kinsella JM, Galliari C, Navone GT. New host, geographic records, and histopathologic studies of Angiostrongylus spp (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) in rodents from Argentina with updated summary of records from rodent hosts and host specificity assessment. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016;111(3):181–191. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760150371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles MR, Navone GT, Kinsella JM. A new angiostrongylid (Nematoda) species from the pulmonary arteries of Akodon azarae (Rodentia: Cricetidae) in Argentina. J Parasitol. 2008;94(2):515–519. doi: 10.1645/GE-1340.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha A, JM, Sobrinho, Salomão EC. Angiostrongilíase abdominal. Primeiro relato de caso autóctone de Minas Gerais. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1991;24(4):265–268. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86821991000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Alegría A, Belhassen-García M, Velasco-Tirado V, Garcia-Mingo A, Alvela-Suárez L, Pardo-Lledias J, et al. Angiostrongylus costaricensis: systematic review of case reports. Adv Infect Dis. 2014;4(1):36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Salb AL, Barkema HW, Elkin VT, Thompson RC, Whiteside DP, Black SR, et al. Dogs as sources and sentinels of parasites in humans and wildlife, northern Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(1):60–63. doi: 10.3201/eid1401.071113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simões RO, Souza JGR, Maldonado A, Jr, Luque JL. Variation in the helminth community structure of three sympatric sigmodontine rodents from the coastal Atlantic Forest of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Helminthol. 2011;85(2):171–178. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X10000398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sly DL, Toft JD, Gardiner CH, London WT. Spontaneous occurrence of Angiostrongylus costaricensis in marmosets (Saguinus mystax) Lab Anim Sci. 1982;32(3):286–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza JG, Simoés RO, Thiengo SC, Lima WS, Mota EM, Rodrigues-Silva R. A new metastrongylid species (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae): a lungworm from Akodon montensis (Rodentia: Sigmodontinae) in Brazil. J Parasitol. 2009;95(6):1507–1511. doi: 10.1645/GE-2013.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt DM. Species of Angiostrongylus (Nematoda: Metastrongyloidea) in wildlife: a review. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2015;4(2):178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiengo SC. Helmintoses de interesse médico-veterinário transmitidas por moluscos no Brasil. In: dos Santos SB, editor. Tópicos em Malacologia: ecos do XVIII Encontro Brasileiro de Malacologia. Rio de Janeiro: Sociedade Brasileira de Malacologia; 2007. pp. 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ubelaker JE, Hall NM. First report of Angiostrongylus costaricensis Morera and Céspedes, 1971 in the United States. J Parasitol. 1979;65(2):307–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente R, Diaz JI, Salomon OD, Navone GT. Natural infection of the feline lungworm Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in the invasive snail Achatina fulica from Argentina. Vet Parasitol. 2017;235:17–19. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas M, Gómez-Pérez J, Malek E. First record of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen 1935) (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) in the Dominican Republic. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;43(4):253–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira FM, Muniz-Pereira LC, Lima SS, Moraes AH, Neto, Guimãraes EV, Luque JL. A new metastrongyloidean species (Nematoda) parasitizing pulmonary arteries of Puma (Herpailurus) yagouaroundi (É. Geoffroy, 1803) (Carnivora: Felidae) from Brazil. J Parasitol. 2013;99(2):327–331. doi: 10.1645/GE-3171.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weksler M, Percequillo AR, Vosst RS. New genera of oryzomyine rodents (Cricetidae: Sigmodontinae) Bull Am Mus Nat Hist. 2006;2(3537):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DE, Reeder DA. Mammal species of the World. In: Johns Hopkins., editor. A taxonomic and geographic reference. University Press; 2005. 142 pp [Google Scholar]

- Zilliota A, Jr, Künzle JE, Fernandes LAR, Prates-Campo JC, Britto-Costa R. Angiostrongiliase: apresentação de um provável caso. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1975;17(5):312–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuñiga S, Cardona V, Alvarado D. Angiostrongilosis abdominal. Rev Med Hondur. 1983;51:184–192. [Google Scholar]